27

BLACK NATIONALISM AND WHITE ETHNICS

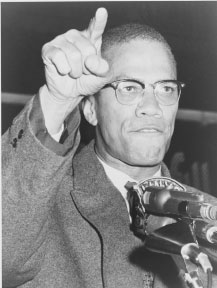

Malcolm X (1925–65), uniquely eloquent as spokesman for the black nationalist Nation of Islam (NOI), was born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, to a black nationalist father who had migrated from Georgia and a mother from the Caribbean Island of Grenada. (See figure 27.1, Malcolm X, 1964.) The family was poor and already peripatetic.1 After a hell-raising early youth, Malcolm landed in a Massachusetts prison with an excellent library, where he educated himself through reading and debating, honing the already popular black notion of a unitary American whiteness he called “the white man.” Released in 1952, he joined the NOI, rising quickly through its ranks as speaker, journalist, and organizer. In 1961, at age thirty-six and having changed his name to a richly symbolic Malcolm X,* he founded the NOI’s national weekly newspaper, Muhammad Speaks, initially publishing out of the basement of his home in Queens. The newspaper grew right along with the NOI movement and America’s civil rights movement in general.

Concurrently, Malcolm X’s Harlem Temple No. 7 became an intellectual as well as a religious center, and a bully pulpit for this peerless speaker. “All Negroes are angry and I am the angriest of all,” he acknowledged proudly, castigating “the white man” in no uncertain terms.2 It was a message that thrilled and chilled Americans of all sorts. Never mind, for the time being, that Malcolm’s skill in debate obscured the plain fact that NOI theory belonged to a long history of flagrantly nonsensical race thought.

The Nation of Islam considered white people—undifferentiated by class, region, or circumstance—as “devils,” “a devil race” of “bleached-out white people,” a single, monolithic entity. NOI theory held that some six thousand years ago an evil black scientist named Yakub had created the white devils through selective breeding out of the original Blackman. Yakub’s white devils would rule for six thousand years, but their time would begin to end in 1914, at the onset of the First World War. Meanwhile, black people should separate from whites, and certainly not seek integration into American society. Because blacks were the targets of racist violence, they should organize into militia for self-defense, such groups to be called the “Fruit of Islam” and dedicated to achieving self-determination.3

Fig. 27.1. Malcolm X, 1964.

Malcolm X’s charisma clearly mattered more than ideology, pulling tens of thousands of black people into the NOI, besotting along the way journalists and scholars of every stripe. In July 1959 Mike Wallace’s five-part television documentary The Hate That Hate Produced considerably amplified media fascination with the Malcolm X story and went on to spawn a Boston University dissertation, scholarly books, a phenomenally best-selling autobiography, and a feature film and commentary that continues to grow. Constantly in demand as a speaker after 1959, Malcolm X became the darling of academia.

By the early 1960s, Malcolm X was the second most sought-after speaker on American college campuses. (The most popular of all was the conservative Republican senator from Arizona, Barry Goldwater, who ran for president in 1964 against labor unions, the New Deal, and the Civil Rights Act.)4 Playboy magazine introduced hipsters to Malcolm through an interview with Alex Haley (Malcolm’s biographer) in May 1963, and the Saturday Evening Post enlightened the masses with a fourteen-page excerpt from The Autobiography of Malcolm X in 1964, a large story opening with a full-page color illustration and the title “I’m Talking to You, White Man.”

Here are a few of Malcolm X’s iconic statements: “When I say the white man is a devil, I speak with the authority of history…. The record of history shows that the white man, as a people, have never done good…. He stole our fathers and mothers from their culture of silk and satins and brought them to this land in the belly of a ship…. He has kept us in chains ever since we have been here…. Now this blue-eyed devil’s time has about run out.”5 To this blanket of blame, descendants of European immigrants, the children of Louis Adamic’s Peter Malek, answered, “Racists? Our ancestors owned no slaves. Most of us ceased being serfs only in the last two hundred years.”6 But few heard them. For the time being, black power garnered all the attention.

Very importantly, Malcolm X brought to blaze the love affair between academia and black nationalists, an attraction that continued after Malcolm’s departure from the NOI in 1964 and his assassination in 1965. The black power movement he inspired propelled Black Panthers onto campuses and encouraged black intellectuals like the novelist James Baldwin to speak their minds openly. In The Fire Next Time, a brilliant essay that troubled white readers, Baldwin called white Americans’ relationship to Europe “spurious” they were hypocrites for Anglicizing their names, pretending to be real white Americans in recognition that the real America never could be only white. Embracing white supremacy and losing their ethnic identities, Baldwin maintained, were the price second-generation immigrants paid for the ticket to American whiteness.7 In 1970 Baldwin and Margaret Mead’s Rap on Race, a best seller, was eclipsed only when black power’s most glamorous symbol, the Black Panther Party founder Huey P. Newton, held a conversation at Yale—later published—with America’s most famous postwar psychologist, Erik H. Erikson.8

Pushed along by an avid media, the black power movement remade the notion of American racial identity.9 Now the most fascinating racial identity was black, not white, a flip certain to disturb those who had struggled so hard to measure up to Anglo-Saxon standards. Working-class whites who resented being ignored, Catholics who felt vulnerable in academia, and Jews who were used to having the last word were all deeply offended. And white people pushed back. The rise of the “white ethnic” identity arose in direct response to Malcolm X and his black power successors.

IF BLACK people could proclaim themselves black and proud, white people could trumpet their whiteness. But therein lay a gigantic problem embedded in the long-standing American tradition of white nationalism. The Ku Klux Klans and white nationalists had already co-opted the white label, leaving “ethnic” for the aggrieved third and fourth European immigrant generations. They were innocent, they maintained, having had nothing to do with slavery or Jim Crow. And they embraced identities rooted in Europe as though it were still the early twentieth century.

But that time had passed. White ethnics could not reenact Horace Kallen’s 1915 version of cultural pluralism, for they no longer spoke the old languages, wore their ancestors’ clothes, or respected their grandparents’ outmoded conventions of gender. The white ethnicity of the late twentieth century was little more than a leisure activity, one that American entrepreneurs embraced. Ethnic consumers could buy T-shirts imprinted with European flags, take tours of the old country, and parade in the street on ethnic holidays. This “symbolic ethnicity” seemed to offer a warm, family-oriented middle ground between stereotypes of plastic, uptight, middle-class Protestant Anglo-Saxons and violent, disorganized impoverished blacks.10

IN THE 1970s the term “ethnicity” shouldered aside older concepts of the white races. To be sure, the distinction between race and ethnicity still remains unclear. As a leading sociologist confessed, “it is true that systems of race and systems of ethnic relations have much in common.”11 To this day scholars and lay people find it difficult to tell race and ethnicity apart. Even the Oxford English Dictionary lists a second meaning for “ethnic”: “Pertaining to race; peculiar to a race or nation; ethnological.” Nowadays race leads directly to race as black, as in the black/white scheme of the South where the civil rights revolution became visible.12 Black power took the concept even further, making black race a positive sign and white race the mark of guilty malfeasance. A correction to the guilty malfeasance part of the equation quickly appeared in print.

MICHAEL NOVAK’S Rise of the Unmeltable Ethnics (1972) became the national anthem of lower-middle-class whites. Born the grandson of Slovak immigrants in the Johnstown, Pennsylvania, steelmaking region, Novak (b. 1933) graduated from Stonehill College in North Easton, Massachusetts, and the Gregorian University in Rome, where he studied for the Catholic priesthood.

Staying with theology, he pursued graduate work at Catholic University and at Harvard, earning an M.A. in 1966. In 1961 he published a novel, The Tiber Was Silver, in which a young seminarian wrestles with ideas of God and tenets of the Catholic Church. As a freelance journalist between 1962 and 1965, Novak covered the Second Vatican Council’s deliberations on the postwar world, then taught at Stanford University and the experimental college of the State University of New York at Old Westbury. In The Rise of the Unmeltable Ethnics, perfectly suited to the times, Novak concentrates on those unmeltable “PIGS,” Poles, Italians, Greeks, and Slavs, in their view so long reviled: “The liberals always have despised us. We’ve got these mostly little jobs, and we drink beer and, my God, we bowl and watch television and we don’t read. It’s goddamn vicious snobbery. We’re sick of all these phoney integrated TV commercials with these upper-class Negroes. We know they’re phoney.” Though they felt detested, the ethnics gloried in judging themselves smarter and harder-working than Negroes and tougher than the college crowd. Novak went along, deploring the “bigotry” he saw in Protestant and Jewish intellectuals so prejudiced against the ethnics and so in awe of black militants.13

Among Novak’s heroes were the straight-talking vice president Spiro Agnew, born Spiro T. Anagnostopoulos in Baltimore, and the Alabama governor George Wallace.* Those tough guys reminded Novak of Slovak men arguing in Johnstown barbershops or his “uncle drinking so much beer he threatened to lay his dick upon the porch rail and wash the whole damn street with steaming piss—while cursing the niggers in the mill below, and the Yankees in the mill above—millstones he felt pressing him.”14 Newly elected governor in 1963, George Wallace had proclaimed “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” and backed up his words by “standing in the schoolhouse door” to protect the University of Alabama from two black students.15 The university did finally admit the students (who eventually became honored alumni), but Wallace won, too, going on to pesky runs for the presidency in 1964, 1968, 1972, and 1976.†

Richard Nixon picked up the theme, running on the Wallace-inspired, antiblack “southern strategy” in 1968, a ploy that served Republicans well past the Ronald Reagan era. Novak reports with pride that Reagan’s pollster had lifted “work, family, neighborhood, peace, strength” from him and used the slogan to rally Democrats for Reagan.16‡ Clearly, as they had for a century, races were still assumed to have racial temperaments, so the depiction of ethnic whites as temperamentally honest and hardworking enjoyed a very long life. At bottom, the southern strategy pitted white people—Americans—against an alien race of black degenerate families judged lacking those self-same virtues. How things had changed from a promising brotherhood of the postwar era to a time of black/white tensions in the 1970s! A classic text soon spanned the two eras, capturing the mood of each moment from an academic point of view.

IN THE late 1950s the sociologists Nathan Glazer (b. 1923) and Daniel Patrick Moynihan (1927–2003) saw a trend and conceived a study of the various racial and ethnic groups in their own New York City. Glazer came from a Yiddish-speaking immigrant background and grew up in working-class East Harlem and the Bronx. He attended City College (where tuition was free); graduating in 1944, he went on to the University of Pennsylvania and to Columbia University, where he earned a Ph.D. in sociology and collaborated with David Riesman on The Lonely Crowd.* During the Kennedy administration of the early 1960s, Glazer worked in the War on Poverty in Washington, D.C., and got to know Daniel Patrick Moynihan, an assistant secretary of labor.

Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Moynihan had moved to New York with his family when he was six. Like Glazer, he lived in poor neighborhoods and studied at City College. However, Moynihan joined the Navy’s officer-training program at Tufts University and received M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from Tufts after the war. In Washington, Moynihan and Glazer decided to work together, with Moynihan adding an essay on New York’s Irish community and a general conclusion to Glazer’s articles on ethnic groups in New York. Their 1963 book, Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians, and Irish of New York City, became one of the most influential sociological studies of its time.17 Glazer joined the Harvard University faculty in 1969, where Moynihan—soon to be elected U.S. senator from New York—had been since 1964.*

In its first edition, Beyond the Melting Pot painted an optimistic picture of various New York ethnic groups (including Negroes and Puerto Ricans) who were competing for power in the city and accommodating one another’s claims. Glazer and Moynihan denied that any of the ethnic groups had melted into a bland Americanness. Ethnic groups were “not a purely biological phenomenon,” and while old country languages and cultures had largely disappeared, ethnic groups were being “continually recreated by new experiences in America.”18

Much of the book’s readability rested on its ready resort to shaky generalization, which occasionally veered awfully close to stereotype.19 The Jews were coming out on top by dint of intelligence and hard work; the bewildered Puerto Ricans could not figure out how to work the system; the Negroes were struggling against a heritage of discrimination, but the urban policies of the Kennedy administration would provide the assistance they needed. The Italians were losing ground, on account of “a failure of intellect.”20 In a mean-spirited aside, Glazer and Moynihan quote “a world-famous Yale professor who, at dinner, ‘on the day an Italian American announced his candidacy for Mayor of New York,’ remarked that ‘If Italians aren’t actually an inferior race, they do the best imitation of one I’ve seen.’ (It was later also said of Mario Procaccino that he was so sure of being elected that he had ordered new linoleum for Gracie Mansion.)” Never mind the Italians; all in all, the future seemed hopeful.

Beyond the Melting Pot appeared in a second edition in 1970 with a very different feel. In a new long introduction, Glazer regretted the rise of black militants who insisted on their uniqueness. Now, he lamented, “we seem to be moving to a new set of categories, black and white, and that is ominous.”21 And that was where American whiteness stood three-quarters of the way through the twentieth century. The civil rights movement, it seemed, had spawned the ugly specter of black power, a source of alienation for white people. Rejecting the burden of white guilt that Malcolm X laid on them, white Americans were morphing into Italian Americans and Jewish Americans and Irish Americans. What they had in common was not being black.* Basically, white versus black now sufficed as an American racial scheme—for the moment.