Eating More Doesn’t

Make You Fat

Let’s imagine a world where calorie counting and eating less of the traditional Western diet are actually the keys to long-term fat loss. Now let’s try an experiment. We’ll divide a group of people in half. We’ll feed one half 120 fewer calories per day for eight years. What would happen? If weight was ruled by conventional calorie counting, the math would be pretty easy. Multiply 120 fewer calories per day times 365 days in a year, times eight years, and the total equals 350,400 fewer calories. Take that sum and divide it by the 3,500 calories in a pound of body fat, and math tells us that these people should have avoided gaining 100 pounds compared with the other group. The math is easy, but it’s incorrect.

Instead, let’s look at a real-life study: the Women’s Health Initiative, a study that tracked nearly 49,000 women for eight years.26 Just as in our experiment, the women in one group ate an average of 120 fewer calories a day than the other group. Remember, that adds up to 350,400 fewer calories. How much lighter was the average woman who ate 350,400 fewer calories?

The answer: 0.88 pound.

That is not a typo. Eating 350,400 fewer calories had less than 1 percent of the impact predicted by calorie math. Eating less of a traditional Western diet does not cause long-term fat loss because this approach incorrectly assumes that taking in fewer calories forces our body to burn fat. That has been clinically proved to be false. Eating less does not force us to burn body fat. It forces us to burn fewer calories. That is why dieters walk around tired and crabby all day. Their bodies and brains have slowed down.

When our body needs calories and none are around, it is forced to make a decision: go through all the hassle of converting calories from body fat or just slow down on burning calories. Given the choice, slowing down wins. Even worse, if we still don’t have enough energy, our body burns muscle, not fat. Studies show that up to 70 percent of the nonwater weight lost when people are eating less comes from burning muscle—not body fat. Only after it’s cannibalized this muscle will our body burn fat.

Want to set someone up to be fatter and sicker in the long run? Slow down her metabolism and take away her muscle tissue. As soon as she gets tired of being hungry and feeling terrible all day every day, she will go back to eating a normal amount of calories but need fewer of them thanks to her slowed-down metabolism and missing muscle. Now her body sees eating a normal amount as overeating and creates new body fat.

In the Journal of the American Medical Association, George L. Thorpe, MD, a physician within the American Medical Association itself, wrote that eating less makes us lose weight, not “by selective reduction of adipose deposits [body fat], but by wasting of all body tissues . . . therefore, any success obtained must be maintained by chronic under-nourishment.”27 It is not practical or healthy to keep ourselves “chronically under-nourished,” so we don’t. Instead, we yo-yo diet. The standard approach to fat loss we’ve all been taught sets us up for long-term fat gain, not fat loss.

Why does our body behave this way? When we do not provide our body with enough essential nutrients (vitamins, minerals, and essential fatty and amino acids) our body goes into “starvation mode.” What does our body want more of when it thinks we are starving? Stored energy. What is a great source of stored energy? Body fat. So when our body thinks we are starving, does it want to get rid of or hold on to body fat? It wants to hold on. What does our body want less of when we are starving? It wants less metabolically active tissue. What type of tissue burns a lot of calories? Muscle tissue. So when our body thinks we are starving, it gets rid of calorie-hungry muscle tissue.

The research is clear: if we want to burn fat and boost our health for the next sixty years as opposed to the next sixty days, let’s not starve ourselves. Think about it like this: Imagine you’re watching TV and you see a commercial for a new medication. The ad tells you the medication slightly improves your vision as long as you keep yourself chronically sleep-deprived. At the end of the commercial, a quieter voice lists the medication’s long-term side effects. One of them is that your vision will become much worse if you ever go back to getting a good night’s sleep. Would you ever use that medication?

Don’t the Laws of Thermodynamics Prove Eating Less Burns Body Fat?

We know the traditional approach to fat loss fails more than 95 percent of the time, yet common sense seems to tell us, “If you eat less and exercise more, you must burn body fat. Anything else violates the laws of thermodynamics.”

Of course not. You can’t go through life exhausted. The temporary benefit isn’t worth the long-term side effects. Sadly, millions of people fall victim to the exhausting side effects of starvation dieting every day.

THE SIDE EFFECTS OF EATING LESS

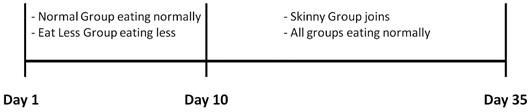

My favorite experiment that demonstrates the side effects of starvation dieting took place at the University of Geneva and involved three groups of rats all eating the same quality of food.

1. Normal Group: Adult rats eating normally

2. Eat Less Group: Adult rats temporarily losing weight by eating less

3. Naturally Skinny Group: Young rats who naturally weighed about as much as the adult Eat Less Group immediately after the adult rats were starved

If the study were conducted on humans, the Normal Group would be typical thirty-five-year-old women. The Eat Less Group would be thirty-five-year-old women cutting calories until they fit into their high school jeans. And the Naturally Skinny Group would be high school girls who fit into size four jeans without trying.

For the first ten days of the study, the Eat Less Group ate 50 percent less than usual while the Normal Group ate normally. On the tenth day

1. The Normal Group kept eating normally.

2. The Eat Less Group stopped starving themselves and started eating normally.

3. The Naturally Skinny Group ate normally.

This went on for twenty-five days and the study ended on day thirty-five.

At the end of the thirty-five-day study, the Normal Group had eaten normally for thirty-five days. The Eat Less Group had eaten less for ten days and then normally for twenty-five days. And the Naturally Skinny Group had eaten normally for twenty-five days.

SETUP OF THE UNIVERSITY OF GENEVA STUDY

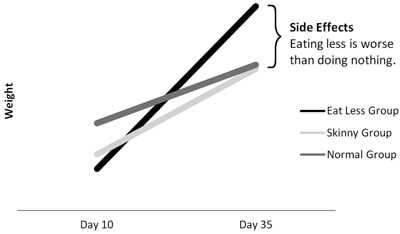

Which group do you think weighed the most and had the highest body fat percentage at the end? The Naturally Skinny Group seems like an easy “no,” since these rats are younger and naturally thinner than the other rats. Traditional fat-loss theory would say the Eat Less Group is an easy “no” as well, since these rats ate 50 percent less for ten days. So the Normal Group weighed the most and had the highest body fat percentage at the end of the study, right?

Surprisingly, no.

The Eat Less Group weighed the most and had the highest percent body fat. Even though they ate less for ten days, they were significantly heavier than those who ate normally all the way through. Eating less caused metabolic adjustments that led the rats to gain—not lose—body fat.

Here are the data:

A SIDE EFFECT OF STARVATION

Talk about side effects. Eating less was worse than doing nothing. Why? After our body survives starvation, its number one priority is restoring all the body fat it lost and then protecting us from starving in the future. It does that by storing additional body fat. Researchers call this “fat super accumulation,” and they believe it is a primary trigger for “relapsing obesity”—also known as yo-yo dieting.29

The most disturbing aspect of fat super accumulation is that it does not require us to eat a lot. All we have to do is go back to eating a normal amount. The Eat Less Group in the study gained a massive amount of body fat quickly while eating the same amount as the Normal Group and the Naturally Skinny Group. Why? The body was trying to make up for the past losses.

Eating less also slowed the metabolism. Subject a slowed-down metabolism to the exact same food and exercise and out comes more body fat. The University of Geneva researchers reported that the Eat Less Group’s metabolisms were burning body fat over 500 percent less efficiently and had slowed down by 15 percent by the end of the study.

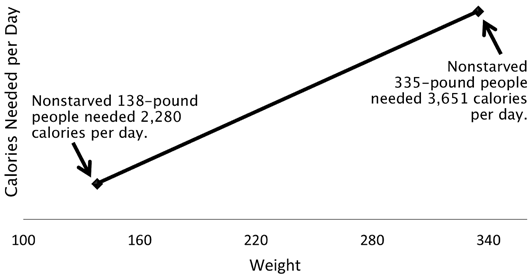

For another example of starvation’s long-term side effects, consider a study conducted by Dr. Rudolph Leibel, director of the Division of Molecular Genetics in the Department of Pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center.30 A group of people weighing an average of 335 pounds starved themselves down to 220 pounds. After the period of extreme calorie restriction ended, the researchers wanted to see what impact eating less had on the 220-pound dieters’ need to burn body fat. To do this they brought in people who were the same age but naturally slim. This gave the researchers three groups of people to compare:

1. Nonstarved 335-pound people

2. Formerly 335-pound people who starved themselves down to 220 pounds

3. Nonstarved 138-pound people

Just as a larger SUV should need more gasoline than a smaller motorcycle, the nonstarved 335-pound people should need more calories than the nonstarved 138-pound people, right?

Yes.

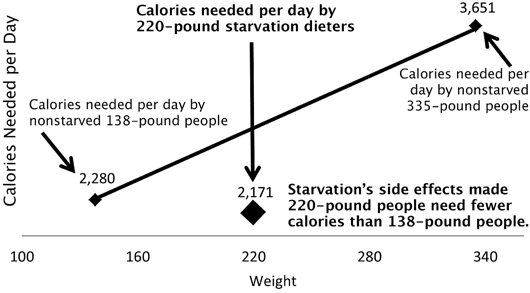

CALORIES NEEDED PER DAY

All things being equal, more body weight means more calories needed per day to maintain and move more mass. So you would think that after losing 115 pounds, the 220-pound people slid right down the graph. Right?

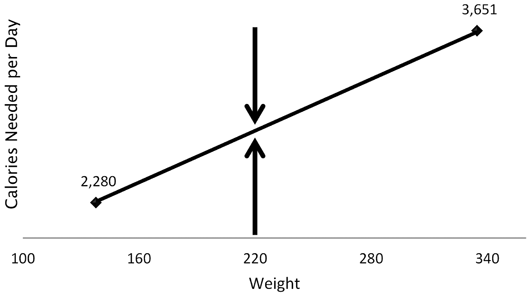

CALORIES NEEDED PER DAY

Not necessarily. It depends on how the 115 pounds were lost. After all, we know that starvation burns calorie-hungry muscle while slowing down the metabolism. So, how many calories did the 220-pound starvation dieters need after having starved away 115 pounds?

CALORIES NEEDED PER DAY BY 220-POUND STARVATION DIETERS

Thanks to starvation’s side effects, the metabolism of the 220-pound subjects slowed down dramatically. In fact, they needed 5 percent fewer calories per day than the nonstarved 138-pound people, even though they had 82 more pounds of mass to move. That is a scary side effect. And that is why Richard Keesey, PhD, of the Department of Psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says, “Disproportionately large declines in resting metabolism are seen in food-deprived men.”31

Similar results were gained from a test done as far back as World War II. University of Minnesota researchers studied starvation to get a better understanding of how to help the hungry in war-torn Europe.32 The researchers recruited people in the United States and had them restrict their daily intake to 1,600 calories.* Subjects’ metabolisms responded by slowing down by a whopping 40 percent. At the same time their strength fell by 28 percent, their endurance fell by 79 percent, and their rates of depression rose by 36 percent.

Let’s focus on the metabolism slowing down by 40 percent for a moment. Say Jillian needs and eats 2,000 calories per day. But now Jillian wants to drop a few pounds for her vacation in two weeks, so she reads a magazine that tells her to starve herself and she cuts back to 1,600 calories per day. According to this study, Jillian’s metabolism would slow down by 40 percent and she would need only 1,200 calories per day. Before Jillian ate less, she needed 2,000 calories per day and ate 2,000 per day. After eating less, Jillian needed only 1,200 calories per day but ate 1,600 per day. When she stops eating less, she will eat 2,000 calories per day while needing only 1,200 per day. That’s not helpful.

In addition to being deprived of their need to burn body fat, as soon as the World War II study subjects stopped eating less, thanks to their set-point, they ate an average of 5,000 calories a day until they gained all the weight they lost back plus 5 percent. That is the good news. The bad news is that their body fat percentage was 52 percent higher than before they starved themselves. All the muscle they burned was replaced by body fat. They experienced fat super accumulation.

THE MORE WE STARVE OURSELVES, THE WORSE OFF WE ARE

Attempting to eat less of a traditional Western diet is counterproductive because it leads to yo-yo dieting, and yo-yo dieting increases our risk of heart attack, stroke, diabetes, high blood pressure, cancer, immune system failure, eating disorders, impaired cognitive function, chronic fatigue, and depression. If that’s not bad enough, the more often we yo-yo, the easier it is to yo-yo for the rest of our lives. “It is only the rate of weight regain, not the fact of weight regain, that appears open to debate,” says David Garner, PhD, professor of psychiatry at Michigan State University.33

In a University of Pennsylvania study, rats yo-yoed up, down, back up, back down, and then back up.34 The second time the rats tried to lose weight by eating less, they lost weight 100 percent more slowly and regained the weight 300 percent faster than the first time they ate less. The rats who yo-yoed the second time stored food as body fat 400 percent more efficiently than rats who constantly ate a fattening diet.

Doing nothing is better than just eating less of the traditional Western diet. This study shows it is 400 percent better.

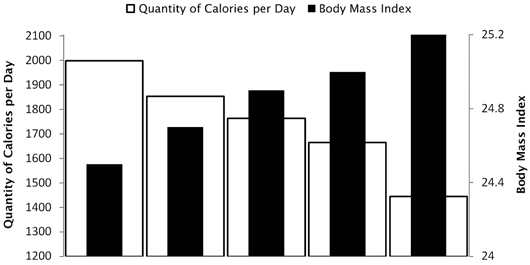

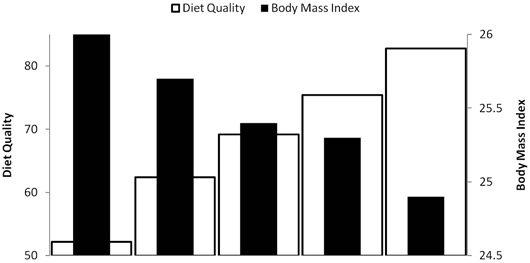

However, even after all this evidence, there still may be a voice in the back of your head saying, “Now hold on. There has to be some truth in ‘eating less means less body fat,’ because that’s what everybody says.” I felt the same way. Then I discovered a Harvard study of 67,272 people.35 The researchers divided this large sample into five groups according to the quantity of calories they ate and found that the less people ate, the more body fat they had. This finding is shown in the following chart, where “Body Mass Index” approximates “body fat.”*

LOWER CALORIES, HIGHER BMI

Hunger is not healthy. Think about starving yourself to burn fat; it’s like drinking salt water to quench your thirst. Both seem as if they should be helpful and they both provide some relief in the short term, but both do more harm than good in the long term. University of California researchers say, “There is little support for the notion that diets lead to lasting weight loss or health benefits.”36 University of Washington researchers say, “Energy-restricted diets are a physiologically unsound means to achieve weight reduction.”37 Starvation does not make us thin. It makes us stocky, sick, and sad. It’s bad for health and it’s bad for fat loss.

EAT MORE, BURN MORE

Eating more low-quality processed foods causes us to gain body fat. But that does not mean eating more high-quality whole foods produces the same result. Interestingly enough, eating more of the right foods has been clinically proved to help us burn fat over the long term. Consider the evidence:

• A study at the University of Connecticut found that people in the eat-more-high-quality-food group ate 300 more calories per day and burned more body fat.38

• A study at the University of Pennsylvania found that people in the eat-more-high-quality-food group ate a total of 9,500 more calories over six months and lost 200 percent more weight.39

• A study published in Obesity Research found that people in the eat-more-high-quality-food group ate a total of 25,000 more calories over three months without gaining any additional weight.40

• A study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health found that people in the eat-more-high-quality-food group ate a total of 65,000 more calories over four months and lost 141 percent more weight.41

How are these results possible? Research suggests two main reasons: First, a calorie is not merely a calorie (more on that soon). Second, more in means more out—only as long as we’re unclogged. Let’s look at how hormonally healing ourselves enables us to restore our natural set-point and to burn—instead of store—excess calories.

Researchers at the Mayo Clinic fed people 1,000 extra calories per day for eight weeks.42 A thousand extra calories per day for eight weeks totals 56,000 extra calories. Nobody gained sixteen pounds—56,000 calories’ worth—of body fat. The most anyone gained was a little over half that. The least anyone gained was basically nothing—less than a pound.

How could that be true? People ate an additional 56,000 calories and gained basically zero body fat? How can 56,000 extra calories add up to nothing?

That’s because extra calories don’t have to turn into body fat. They could be burned off automatically. The medical journal QJM reports, “Food in excess of immediate requirements . . . can easily be disposed of, being burnt up and dissipated as heat. Did this capacity not exist, obesity would be almost universal.”43

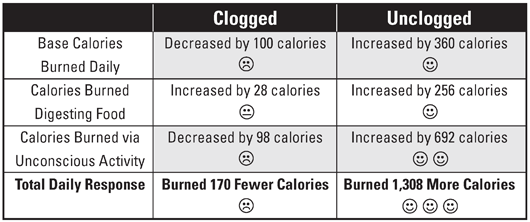

Eating more and gaining less is possible because when we’re hormonally healthy, we have all sorts of underappreciated ways to deal with calories other than storing them as body fat. In the Mayo Clinic study, researchers measured three of them:

1. Increase the amount of calories burned daily.

2. Increase the amount of calories burned digesting food.

3. Increase the amount calories burned via unconscious activity.

Here is what they found:

Daily Response to 1,000 Extra Calories

That is how some people ate 56,000 extra calories and instead of storing the excess calories as body fat, gained virtually no weight. A lower set-point does its best to automatically balance more calories in with more calories out by upping the calories we burn keeping ourselves alive and digesting food, and via unconscious activity.

There is no shortage of proof. Take a study performed by researchers at Harvard Medical School and King’s College, London University. Students were divided into two groups according to the “ease with which they maintained a relatively lean body weight.”44 The researchers called the group that maintained their weight without trying “lean.” I call them unclogged. The researchers called the students who struggled with their weight “postobese.” I call them clogged.

While participants in both groups were similar in age, gender, size, and activity level, and all maintained a steady body weight throughout the study, their metabolic profiles varied in two major ways. First, the students who struggled with their weight actually ate less than their effortlessly lean counterparts “by 30 percent per kilogram of body weight.” Second, the unclogged students automatically burned more than 500 additional calories per day compared with their clogged peers. In other words, the unclogged students ate significantly more and burned significantly more than the clogged students, all factors being equal.

The study doesn’t stop there. The researchers then went on to feed all the participants 300-calorie meals and discovered that “the overall thermogenic [calorie burning] response of the [clogged] subjects to the 300 calorie meal was only half that measure in the [unclogged] subjects.” Again, when they ate more, the unclogged participants automatically burned more and the clogged participants automatically stored more. The researchers concluded, “These findings provide further evidence for a subnormal thermogenic [calorie burning] response to food in those with a predisposition to obesity.” Clogged individuals do not gain weight because they eat a lot and exercise too little. This and many other studies show that overweight people eat significantly fewer calories and are as active as naturally thin people. This is not an issue of gluttony or laziness. The issue is biology: Their bodies have lost their natural ability to stay slim, to burn more when they eat more. It’s not a moral issue. It’s not a willpower issue. It’s a metabolic issue.

We know that the weight-loss advice we commonly read in books and see in the media isn’t helping us. Eating less of the standard American diet and doing more of a traditional exercise program doesn’t cause long-term weight loss. So where can we turn? There must be an institution that can provide us with reliable information on health and weight loss. How about our own government guidelines and regulations?

Sadly, the information coming out of government institutions isn’t as reliable as you might think. In fact, the very people responsible for teaching us about eating and exercise—the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)—don’t seem to be up on the latest science. Take this excerpt from chapter 3 of the USDA’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans: “Since many adults gain weight slowly over time, even small decreases in calorie intake can help avoid weight gain.”45

If “small decreases in calorie intake” lead to gradual weight loss, does that mean “small decreases in calorie intake” will eventually make us weigh nothing? Of course not. Why? Because we’re dealing with biology, not math. But if that is true, then how can a small decrease in calorie intake help us practically avoid weight gain long term?

It can’t.

The issue is not that our body wants us to weigh less but that too many calories per day are blocking it. The issue is that our body does not want us to weigh less thanks to our elevated set-point. The same mechanism preventing “small decreases in calorie intake” from making you weigh nothing (your set-point) also prevents your body from burning off excess fat effectively right now.

When you think about how hard every living organism works to maintain balance, our set-point weight makes perfect sense. What doesn’t make sense is the advice of many respected health institutions on this topic, such as the American Heart Association, which advises, “How can you manage your weight in a healthful way? The answer is simple: balance the calories you take in with the calories you burn.”46 That advice is especially troubling since the AHA also published a piece in its journal, Circulation, noting, “Few reliable data are available on the relative contributions to this obesity epidemic by energy intake and energy expenditure.”47 If “few reliable data are available,” then what is the basis for its recommendations?

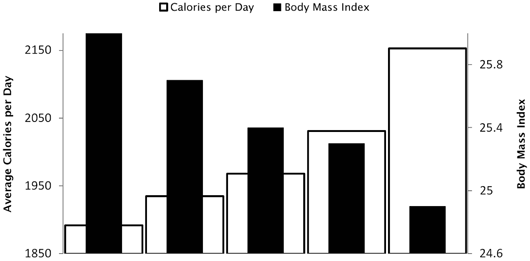

Here’s what the data actually show. Harvard researchers looked at the eating patterns of more than 50,000 people, divided into fifths, according to the quantity and quality of calories they ate.48 This large sample demonstrated two points:

1. Eating more correlated with less body fat.

2. Higher-quality food correlated with less body fat.

If we can escape the trap of old calorie-quantity (versus calorie-quality) myths, we will never have to worry about our weight again. Now let’s take a look at how we can increase the quality of our exercise to start burning more fat in less time.

MORE FOOD, LESS BODY FAT

HIGHER QUALITY, LOWER BODY FAT

From Short-Term Weight Loss to Long-Term Health: Jay and Jennifer Jacobs’s Story

Jay and Jennifer Jacobs inspired a nation with their nearly 300-pound combined weight loss while on NBC’s Biggest Loser. While they were thrilled with the results they got from dedicating every hour of their lives to calorie counting and extreme exercise, Jay and Jennifer knew they had to find a more sustainable approach once their lives got back to normal. As Jay put it, “I have lost 100 pounds five times. Weight loss doesn’t seem to be the issue. The challenge is keeping it off. That’s exactly what we found when the show ended. It was like our bodies wanted to put the 300 pounds back on. Almost like they had a mind of their own. Little did we know, they basically do! It’s our set-point.”