CHAPTER FIVE

Teaching Emerging Adults

Guidelines for Young Adults Eighteen to Twenty-One Years Old

YOUR SON OR your daughter will always be your child, but at this stage, they hardly seem like children any longer! They have finished high school and have emerged from adolescence into young adulthood. They have now reached the age of majority, which means they can legally take on more responsibilities: voting, entering into contracts, serving on a jury, or even marrying! They may also be considering going on to college or university.

Post-secondary study is a good example of the concept of “opportunity cost” — the most valuable alternative you give up by choosing another, mutually exclusive option. Some kids at this age may be tempted to start working full-time and earning money rather than going on to do further studying. But, while students who go on to university or college give up the opportunity to earn income right away, they expect that they will more than make up for it with higher earning potential after they graduate. Arguably, a university education more than pays for itself over time, and the opportunity costs in this case are minimal. In other situations, the opportunity costs may be significant. Say your child is considering two very different career paths: investment banker or social worker. The opportunity cost of choosing a career as a social worker rather than an investment banker is quite high in terms of forgone earnings. It may still be the right choice for your son or daughter, based on many other considerations, but encourage them to think carefully about alternatives and to consider the opportunity costs when making decisions.

“The more you learn, the more you earn.”

— WARREN BUFFET

“My parents made me and my brothers get summer jobs working in a factory or doing manual labour. They wanted us to appreciate the value of an education and the opportunities it afforded us. After just a few days on a construction site, it was very clear to me that I wanted a stimulating career, one that was more mental than physical.”

Earn

Your kid may be one of the fortunate ones; that is, they may know they can count on you to pay for their university education, which allows them the luxury of not working and gives them more time to focus on their studies during the school year. Or maybe your kid will be working part-time during the school year or full-time during the summer to help pay for university. If your kid didn’t work as a teenager, you may want to go back to Chapter Four and read the sections entitled “Their First Real Job” and “Helping Them Understand Their Paycheque.” This is also a good time to talk to them about the responsibility of filing a tax return.

Throughout high school, Emma Taylor worked part-time at the Gap with her friend Allison. After graduation, Emma went to university out of town. Allison’s family couldn’t afford to send her away to school, so she lived at home and went to university. She also needed to keep working to help pay her tuition. Allison debated the pros and cons of keeping her job at the Gap. On the one hand, she had a track record of good performance and she had a little seniority, plus she wouldn’t have to embark on a job search. On the other hand, as Emma pointed out, she might be limiting herself if she stayed. Prospective employers want people who have had experience at a variety of jobs in different fields. Allison agreed that different work experience would be good — she knew she didn’t want to work at her Gap job forever — so she decided to look for a more challenging, better-paying job in her area of interest, using the tips outlined in Chapter Four. She ended up finding a position at the university, which employs a lot of students in different administrative, service, and teaching-related positions.

Why File a Tax Return?

Some kids may not see the point of filing a tax return, especially if they haven’t made very much money. If you are a resident of Canada for all or part of a tax year, you must file a tax return if you either owe tax or you think you may be entitled to a refund. Generally, you must file your return and pay your taxes by April 30 of the year following the tax year. As we discussed in Chapter Four, if your kid’s taxable income falls under the Basic Personal Amount ($12,069 in 2019), then it’s unlikely that they will owe tax.

We will discuss RRSPs and TFSAs in the next section.

|

Family Discussion Needs versus Wants |

|

Reasons to File a Tax Return: • To recover any overpaid tax or other source deductions (e.g., CPP, EI) that your employer may have withheld from your paycheque and remitted to the government. • To create contribution room in a Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP). |

|

Things to Do Tax Credits |

|

Claim tax credits for: • Tuition fees • Moving expenses |

Tax Breaks for Students

Students are entitled to a tax credit for their tuition fees, which can be used to reduce any income taxes they owe.

There are rules that set out eligible expenses, and form T2202A, Tuition and Enrolment Certificate, must be completed. You can learn more by visiting the Canada Revenue Agency’s website at www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/forms-publications/publications/p105.html.

Your child must claim the tuition first, even if you are the one paying. But if your child doesn’t need all of the credit to reduce his or her income (e.g., because it’s already below the Basic Personal Amount), then up to $5,000 can be transferred to your return to reduce your taxes (or to a grandparent’s). The credit can also be carried forward indefinitely and claimed in any future year.

If your child is moving to attend full-time post-secondary studies, they may be able to claim eligible moving expenses if:

• they receive scholarships and bursaries while at school that are included in their income; and

• they are moving at least forty kilometres away to attend school.

Scholarships and Bursaries

If your child receives a scholarship, fellowship, or bursary, the income will not be subject to tax if she is enrolled in an educational program as a full-time qualifying student. If your child is a part-time qualifying student, the scholarship exemption is equal to the tuition paid plus the costs of program-related materials. Details on the calculation can be found at www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/forms-publications/publications/p105/p105-students-income-tax-2016.html#chart.

Save

Some young adults decide to work full-time after high school, which means they are in a position to begin a savings program or to contribute more to a savings program that they’d started earlier. On the other hand, if your child is attending university or college, these are likely to be spending, not saving, years. She may have some short-term savings goals from time to time, but if she’s earning any money, most of it is probably being spent on university tuition, books, and living costs. Your kid probably has a savings and/or a chequing account for managing day-to-day spending; if you haven’t done so already, review the basic mechanics of managing a bank account, which we covered in Chapters 3 and 4. It’s also worth the time to investigate whether your bank offers a special account for post-secondary students. If they do, your child may be entitled to services at discounted prices. Because you have already introduced your kid to the topic of income tax, take this opportunity to discuss using tax-advantaged savings vehicles as a way to minimize taxes.

Tax-Advantaged Savings

Tax-Free Savings Account

A TFSA is a special savings vehicle for Canadians aged eighteen or older. The annual contribution limit is currently $6,000 (indexed for inflation in $500 increments). Contributions to the account are not tax-deductible — they come out of after-tax earnings. However, income earned inside the account isn’t subject to tax, nor are amounts withdrawn. If you withdraw an amount from your account, you can re-contribute that amount in the following year, in addition to that year’s limit. If you don’t have the funds to contribute, you can carry forward that amount indefinitely.

For these reasons, a TFSA is a very flexible tool for saving. It can be used to save for a down payment on a house or for an emergency fund, for example. Once you decide what you are saving for, you can choose the appropriate investments to hold, and any income is earned tax-free, allowing your savings to grow more quickly. We will discuss investing later in this chapter.

Registered Retirement Savings Plan

If your kid’s income doesn’t all have to go toward college or university expenses, starting an RRSP can be a good idea. Make sure they know the basics of how RRSPs work. An RRSP is a savings vehicle created by the government to help Canadians save for retirement. Unlike a TFSA, amounts contributed to an RRSP are tax-deductible — they come out of pre-tax income, not after-tax earnings. The funds inside an RRSP are invested, and the investment income earned inside an RRSP isn’t subject to tax. This means the investments can grow more quickly to help you reach your long-term goals. And remember, the power of compounding means that even a little bit saved early and often can make a big difference over time.

You must have earned income in order to contribute to an RRSP. There are rules about how much you can contribute each year, and you must file a tax return. The funds are not taxed until withdrawn at retirement, unless you decide to take the funds out early. There is a special exception for withdrawals made by a first-time homebuyer to purchase or build a qualifying home. In that scenario, you may withdraw up to $35,000 tax-free from your RRSP, but you must repay the money to your RRSP within fifteen years.

The “Latte Factor”13

Saving money is challenging for most people, especially for students, who may feel like they’re living a bare-bones existence in order to make ends meet. If your kids (or you) are looking to save a few dollars every week, you may want to examine your “latte factor.” Everybody has one — it’s those little indulgences and the wasteful spending that you could either cut back on or eliminate altogether. Examples are fancy coffees, bottled water, or fast food. Giving up unhealthy and expensive habits like smoking is another great example. We often don’t even realize how much we’re actually spending on these little purchases, but they add up! Changing your habits may mean more money to pay for tuition and other costs of living.

Spend

When your child decides to go to university or another post-secondary institution, they’re taking the first big step toward independence, a career, and financial security. It can be quite a challenging time, especially if they’ll be living away from home in a different town or city for the first time. And because the cost of a university education is substantial, financial planning will be required.

Paying for Post-Secondary Education

There are different ways to finance a university education, and they’re not mutually exclusive. Depending on your circumstances, you may find yourself using some combination of your savings, which may take the form of withdrawals from an RESP; your current earnings/cash flow; scholarships or grants your child may receive; your child’s savings; or their own earnings.

Finally, there are loans — either student loans or amounts borrowed from a personal line of credit or from other sources. This kind of debt is an example of good debt; a university education is an investment in your child’s future career and earning power. However, they still need a plan to pay off that debt within a reasonable period of time. Carrying that much debt may delay or alter other goals, such as travelling, buying a house, or getting married.

If your child does get student loans, under the Canada Student Loans Act, the Canada Students Financial Assistance Act, or similar provincial or territorial government laws, they can claim most of the interest paid as a tax credit. If they don’t use the credit, they can carry it forward for five years. The tax credit cannot be transferred to anyone else, even if someone else paid the interest on the loan. Also, they cannot claim interest paid on any other kind of loan, such as a personal loan or line of credit.

Perhaps an ideal solution to the issue of paying for university is a co-op program, which also gives participants valuable work experience. Many universities offer these programs and help arrange the placements, which are usually for one semester. Students are paid for their work during that period and return to school at the end of the placement. Although working in a co-op program may mean it will take longer for the student to graduate (since students don’t normally get credits for their work terms), the additional income is necessary for many kids to complete their education. And the practical experience can be invaluable: these placements often lead to permanent job offers if the student performs well, as well as opportunities to expand their professional networks. Even in the absence of a job offer, co-op placements give the student an opportunity for some real-world experience in his chosen field and can help him make a more informed career choice.

Are Your Kids Prepared to Be on Their Own?

In Chapter Four we introduced budgeting for teens, getting them used to the responsibility of managing their money, even though you were still taking care of most of their needs. Once they emerge into adulthood, whether into the workforce or off to university, they will need to be even more in control of their financial situation. They will need to know what is coming in and what is going out as they try to balance the inflow and outflow.

Your child should get into the habit of tracking his spending — it’s really the only way to bring awareness to where the money is going. The accountability that comes with careful tracking can lead to making better spending choices. It will also let him compare his actual spending to his budget, to see where he’s on track or where he may be over or under budget. Budgets are dynamic, and they need to be reviewed regularly — and sometimes revised.

What do you do if your kid keeps running out of money every month? First, review the budget and the actual spending to try to identify the problem area. If there is enough money to cover the basics (the fixed expenses), the problem may be discretionary spending on things like entertainment and eating out. Remember the three Cs — create, convert, and conserve — which we discussed in Chapter One. He may have to cut back on some of these expenses or make more money.

“I got through university by taking full advantage of student discounts and always asking if there was a student rate for things like haircuts, gym memberships, or theatre tickets. I also got into the habit of using coupons or two-for-one promotions when I went out for dinner with my friends. And whenever we felt like seeing a movie, we made sure to go to the ‘cheap Tuesday’ shows!”

|

Family Discussion Budget |

|

• Encourage your child to create a realistic budget — based on weekly, biweekly, or monthly amounts — using the Post-Secondary Student Budget at the end of this chapter. • Remind them that it’s better to be conservative in their planning than to run out of money: — Caution them not to overstate income. — Remind them to be specific and realistic about expense categories. — Be sure to include unusual expenses that may only occur once a year (such as moving costs, insurance, or holiday gifts). |

Credit Cards Revisited

Once your child has reached the age of majority in your province, she can get her own credit card. A credit card can be very helpful in case of emergency. (No, joining her friends for dinner or going shopping isn’t an emergency!) If your kid has been using your credit card for the last few years and isn’t the one paying the bills, they may be quite naive about the responsible use of credit cards. If they get their own card, make sure the credit limit is low and try to find a card with no fees. Some cards even provide student discounts on purchases.

Credit is very easy to get and use. Many financial institutions offer credit cards specifically targeted to students, and they’re marketed heavily on campuses. Paying by credit card is so convenient that it practically encourages spending. If you had to go to a bank and line up at the teller to take out cash every time you wanted to buy something, you would probably spend a lot less. These days, it’s easy to withdraw cash from all the conveniently located ATMs, but it’s even easier to just whip out a credit card or phone, then tap and worry about it later.

Once again, the best way to teach your kids to use credit cards responsibly is to model this behaviour yourself. Let them know that you pay off your credit card balance each month. Explain to them that the credit card is used for convenience, but that it’s a very expensive way to buy things you can’t afford.

“I was really happy about the new regulations requiring credit card companies to provide information on the time it would take to fully repay the balance if only the minimum payment is made every month. I read my kids the paragraph at the top of my most recent monthly statement for my credit card, which charges 20 percent interest: ‘The estimated time to pay your $1,526.57 balance in full if you pay only the Minimum Payment each month is: 12 years and 2 months.’ That’s a rude awakening — my kids were in a state of shock — I think the message really hit home!”

|

Family Discussion Credit Cards |

|

Make sure they understand the basics of credit card use: • Credit cards let you make purchases, up to a predetermined credit limit, that are billed at a later date. • Ideally, you pay off the balance on the due date every month. If not, you must make a minimum payment every month, and unpaid balances are subject to interest charges based on an annual percentage rate (or APR). • The APR on some cards can be as high as 20 percent. Most cards also charge an annual fee, and there are fees and penalties for late or missed payments. Discuss the benefits of credit cards: • They’re convenient and practical. • They allow you to create a credit history and earn a credit rating. • They let you earn rewards, such as frequent flyer miles or cash-back payments. • They can be used to pay for online purchases. Discuss the risks and disadvantages of credit cards: • They can damage your credit rating if you miss payments or your payments are late. • They’re more expensive than personal lines of credit because the interest rate charged is much higher. • If not used responsibly, credit cards can lead to increased spending and bad debt. |

If you feel your child is ready for the responsibility of a credit card, encourage him to take the time to choose the right credit card. The Financial Consumer Agency of Canada has excellent resources about credit cards and other financial topics available at www.canada.ca/en/services/finance/debt.html.

Fraud, Scams, and Identity Theft

Fraud can take many forms, including scams involving fake emails or websites, identity theft, credit card fraud, and debit card fraud. Anyone can be a victim of fraud, and it’s often costly — in terms of financial losses and in the time it takes to clear your record. Teach your young adult how to protect herself and her financial information with the following tips.

Preventing identity theft

Identity theft occurs when your personal information or identity is stolen for the purpose of accessing your financial accounts to steal your assets or incur debt in your name. Take precautions to protect your personal information at home, in public, on the phone, and online.

|

Things to Do / What Not to Do Identity Theft |

|

• Never provide personal information to anyone unless you know and trust the person and understand why they need it. • Never email or text your personal information. • Keep documents such as birth certificates, passports, or Social Insurance Number cards in a secure and safe place — not in your wallet. • Use only secure websites. • Update your antivirus software regularly. • Shred all documents that include your personal financial information, e.g., old bank statements and credit card statements. |

Preventing credit or debit card fraud

Credit and debit card fraud occurs when your credit/debit card information or your PIN is stolen and used to make unauthorized purchases or transactions. This is yet another reason to set up notifications for real-time spending in your mobile banking app.

|

Things to Do / What Not to Do Credit and Debit Card Fraud |

|

• Get a credit/debit card with chip technology. The embedded microchip is encrypted and virtually impossible to replicate. • Don’t share your credit/debit card or PIN. • Never leave your credit/debit card unattended (or in your car’s glove compartment), and make sure you get it back after payment. • Cover the keypad when entering your PIN. • Check your statements every month (or more frequently online) for errors or unauthorized transactions. Notify your bank or other financial institution immediately if something is amiss. • Destroy cards you no longer need or use. |

A note about social media

The popularity of social media sites makes it very easy for fraudsters to obtain personal information that can be used to decode passwords. Also, announcing your upcoming vacation or attendance at an event on a specific evening is like drawing a map to an empty apartment or house. You may come home to find your valuables missing, including the priceless personal information someone needs to steal your identity.

Share

Volunteering Your Time

Most students don’t have much money for themselves, let alone enough to give away to others. But sharing isn’t always about money — sometimes it’s about volunteering your time and talents to help others. The idea of community service isn’t new — most students are now required to do some volunteering in order to graduate from high school. Although it’s not usually mandatory in post-secondary studies, many students, despite the time pressures from their studies, choose to volunteer for two reasons — because volunteering aligns with their values, and because of the many benefits they receive. Depending on the type of volunteer work they do, students can expand their network, learn new skills, gain work-related experience, have an adventure, and feel good about giving back.

When looking for volunteer work, one of the most important considerations is passion. If your child doesn’t already know what he or she is passionate about, ask them to complete or review their Values Validator (at the end of Chapter One). This exercise will help them clarify what’s really important to them, which will lead them to causes or organizations that they really care about. When you are not being paid for your time and efforts, passion is essential in order to remain committed. Before your child commits to a specific organization, it’s a good idea for them to make sure they know exactly what the organization expects from them in terms of the nature and quantity of work involved. Depending on how formal the organization is, they may even want to get it in writing, so there are no misunderstandings later on.

Philanthropy is a Family Affair

In families where philanthropy is a key family value, the importance of sharing is taught at an early age and carried through to young adulthood.

“When my kids were young, they each had a charity piggy bank, and part of their allowance always went in there. When they became older, I set up a donor-advised fund to provide more structure to their giving. [A donor-advised fund is a charitable-giving vehicle administered by a third party to manage charitable donations on behalf of a family.] Each of my kids, aged nineteen and twenty-one, worked with a donor advisor and also attended a seminar to help them identify their philanthropic leanings. My daughter used her portion to sponsor raincoats for schoolchildren living in the rain-soaked mountains of Ecuador. My son, who played saxophone for his school band, supported a music program at a local school for at-risk children.”

Gratitude

Helping others opens your children’s eyes to the fact that not everyone lives the same way they do and teaches them to be compassionate. It can also help put things into perspective if they’re developing a sense of entitlement. Gratitude doesn’t seem to come naturally because our minds resist making downward comparisons (upward comparisons, as discussed earlier regarding social media and FOMO, happen more naturally). Being grateful takes practice until it becomes a habit.

|

Things to Do

|

|

• Encourage and model an attitude of gratitude. Ask your kids what they’re grateful for today or this week. • Suggest they keep a gratitude journal to jot down each day (or each week) three things that happened that they’re grateful for. |

Invest

Long-Term Investing: Start Early and Invest Regularly

Some people at this age, whether they’re in university or working full-time, have more money than they need to cover their ongoing current expenses. The temptation is to see any extra funds as spending money, but it’s a good idea to earmark some of it for investment. Emerging adults have decades ahead of them to invest, which gives them a huge advantage — time! Encourage your kid to start early and invest regularly, even if the amounts are small.

Emma Taylor began saving $5 each week when she was fifteen. Assuming Emma earned a 5 percent compound annual return, at sixty-five she would have $57,152. If she waited ten years and didn’t start until age twenty-five, she would have $32,978.34 at age sixty-five. And if she waited even longer, until she was thirty-five, and saved for thirty years, she would have only $18,137.81.

See also the Compound Interest Calculator at www.getsmarteraboutmoney.ca/calculators/compound-interest-calculator.

When investing for a long-term goal, a much longer time horizon means you can choose investments with growth potential. Take advantage of time and let compounding work for you, as we saw in Chapter Four. Depending on your tolerance for risk, you may have many different investment options.

|

Family Discussion Investments |

|

Bonds: • Explain that bonds are simply IOUs — they’re debts issued by companies or governments. • They usually pay a fixed or floating rate of interest to the investor for a specific period of time, called the “term.” • The interest rate is expressed as a percentage of the investment. • Bonds issued by governments in the developed world are generally thought to be safe investments, and, if the government has a good track record, the interest rate you earn will be relatively low compared to bonds issued by entities that are considered riskier. • Remember: low risk = low reward. Stocks: • Explain that stocks represent an ownership stake in a company. • The owners of a company’s stock are called shareholders. • Some stocks are traded on public stock exchanges, and their prices are determined by buyers and sellers. • Stock prices can be quite unpredictable in the short run: they can go up or down, and there are no guarantees regarding the safety of your investment or the return of your original capital. You could double your money, lose your entire investment, or come out anywhere in between. For this reason, stocks are said to be risky. • You wouldn’t buy stocks if you were investing for a short-term goal: you won’t have enough time to recover if the stock price falls drastically right before you need the money. |

Stocks, Bonds, and Other Investments

There are three traditional categories or classes of investments: cash, bonds, and stocks. There are also other types of investments, such as real estate, precious metals like gold and silver, and investments in private businesses. But when teaching your young adult, focus on the three traditional ones — the others are generally for more sophisticated investors with substantial investable assets.

In investing, there is a direct relationship between risk and return. Lower-risk investments, like cash or bonds, have lower returns. Higher-risk investments, like stocks, have the potential to earn higher returns. Your child may have learned some of these concepts in a high school business class, but it doesn’t hurt to review the basics if she shows interest.

Everyone has to assess their own comfort with risk. Some investors are very comfortable owning a high-risk portfolio, while others are very uncomfortable with the gyrations of the market and the possibility of losing their principal. But if you are willing to take some risk by owning stocks, the potential returns are also higher than they are with less risky investments like GICs or bonds. Most publicly traded stocks are also very liquid, meaning you can sell them at the prevailing market price quite quickly and easily.

When you own stocks, you can earn investment income in two ways: dividends and capital gains (or losses). Dividends represent a proportionate share of the profits of a company and are paid by some companies to their shareholders; the decision about whether to pay a dividend on common shares (and how much to pay) is made by a company’s board of directors. A capital gain is the difference between what you pay for an investment and what you sell it for, less any transaction costs. If the difference is positive, you have a gain; if it’s negative, you have a capital loss.

|

Family Discussion Investments |

|

Before moving on to the next steps of asset allocation and security selection, ask your child to answer the following three questions. Writing the answers down will help them create an investment plan: • What are your investment objectives? • What is your time horizon? • What is your risk tolerance? |

Asset Allocation and Security Selection

Once your young adult knows what he wants to achieve and when, he can decide how to achieve it with the proper asset allocation and securities. Asset allocation is the process of determining how the money in your investment portfolio should be divided among the different categories of investments: stocks, bonds, cash, real estate, and others. Getting the asset allocation right for the investor’s circumstances is crucial because, according to the oft-quoted Brinson, Hood, and Beebower study,14 it accounts for over 90 percent of the variability of the returns on a typical investor’s portfolio. Contrary to popular belief, it’s a much more important step than security selection. Security selection accounts for only 4.6 percent of the variability. But people tend to focus on picking stocks and other securities because it’s “sexier” and may give them something to brag about!

Fintech and Robo-Advisors

Innovation in financial services has led to the creation of “robo-advisors” (sometimes called digital portfolio managers), which are essentially software-driven investment management solutions that use technology to simplify every part of the investment process, including onboarding, portfolio construction, rebalancing, tax-loss harvesting, and reporting. The use of technology (and the absence of traditional brick and mortar offices and branches) brings down the cost compared to traditional alternatives like full-service brokers.

Wealthsimple is a popular Canadian online investment management service focusing on the millennial investor. In addition to the ability to set up automatic contributions to your Wealthsimple account so you can pay yourself first, they introduced a feature called Roundup to help turn spending your money into investing your money. Roundup rounds up your credit and debit card purchases to the nearest dollar and then invests your spare change so it works harder.

Responsible Investment

Young people today are environmentally and socially minded, and they want their investments to not only make money but to also make a positive impact on society. Responsible investment is an umbrella term for a broad range of approaches that can be used to incorporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations into the investment process. (It’s sometimes also called “sustainable investment”.)

ESG integration refers to the environmental (e.g., pollution, clean water, climate change), social (e.g., human rights, gender equity, impact on community), and governance (e.g., board independence, conflicts of interest, ethical governing principles) factors of an investment that may have a material impact on its performance. Investments can be evaluated on ESG factors, along with more traditional financial measures.

Socially responsible investing (SRI) goes a step further, using ESG factors as either a negative or positive screen, actively eliminating or selecting investments according to specific ethical guidelines. Examples include avoiding investments in companies that harm the environment, make people sick, or violate human rights. It can also mean choosing companies that strive for gender equity. SRI lets young adults put their money where their values are and generate investment returns without violating their social conscience.

Finally, impact investing refers to investments made with the primary intention of generating a measurable, beneficial social or environmental impact. Making a positive financial return is a secondary concern.

A Tale of Three Investors

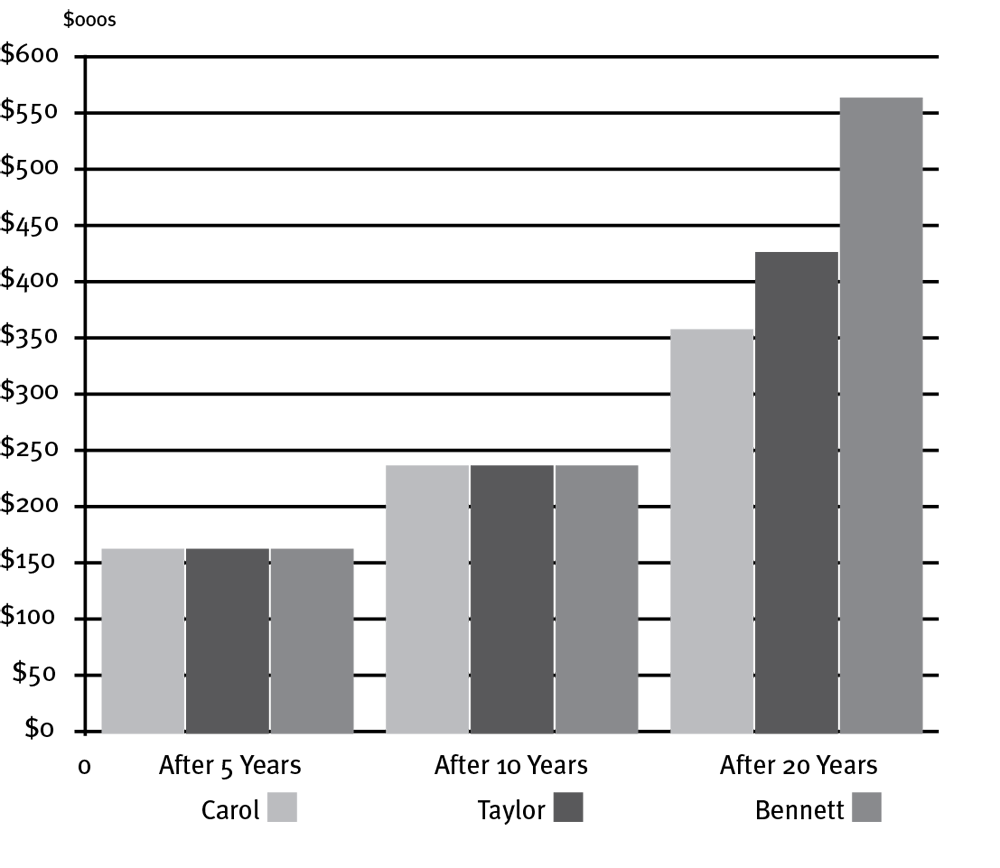

The Taylors are moderate investors who are most comfortable with a balanced portfolio: 50 percent stocks, 40 percent bonds, and 10 percent cash.

Their friends the Bennetts have a greater appetite for risk and prefer to hold a more aggressive portfolio: 70 percent stocks, 20 percent bonds, and 10 percent cash.

Their friend Carol is widowed and is ultra-conservative. She’s very risk averse, and although she will have a small pension, she’s only comfortable owning GICs.

Let’s assume that they each invest $100,000 and plan to reinvest any investment income they earn. How can we expect their portfolios to perform after five years, ten years, and twenty years?

Generally, ultra-conservative portfolios will grow very slowly, and although there is no risk that you will lose your principal, there is a risk that the returns will not outpace inflation and that therefore you may outlive your money. This is in fact what happened to Carol. Although she was outperforming the other two portfolios after five years and staying even after ten, she fell far behind after twenty years. As the Taylors and the Bennetts experienced, a more aggressive asset mix means more growth potential but also more likelihood of experiencing losses. In this example, the stock market was volatile in the first ten years, and the more aggressive portfolios didn’t really start to perform well until the second decade.

|

Investor |

Portfolio |

Initial Investment |

After 5 Years |

After 10 Years |

After 20 Years |

Average Annual Return |

|

Carol |

Ultra-conservative |

$100,000 |

$161,049 |

$236,206 |

$356,484 |

6.7% |

|

Taylors |

Balanced |

$100,000 |

$154,330 |

$236,103 |

$424,785 |

7.5% |

|

Bennetts |

Aggressive |

$100,000 |

$129,503 |

$236,736 |

$560,441 |

9.0% |

Key Points

• Young adults become increasingly independent from you, but you can still have a lot of influence on them — they’re often more willing to discuss important matters with you than they were just a few years earlier.

• Help them see that their newfound independence involves both privileges and responsibilities, i.e., they can work at more interesting jobs that pay them more, and as students they’re entitled to certain tax breaks, but they have to file an income tax return to make sure they’re taking full advantage of everything they’re entitled to.

• Volunteering is a great way for young people to put their values into action, and it pays dividends in terms of real-world experience and personal satisfaction.

• It’s a good idea to make sure they have good, basic invest-ment knowledge. Some may already be in a position to start a portfolio; others will benefit from knowing what their options are when they do start to invest.

Chapter Five Resources

Post-Secondary Student Budget

This worksheet can be downloaded at cpacanada.ca/flworksheets

This form will take about five minutes to complete. Please fill in as many of the fields below as possible with your household after-tax values to ensure an accurate estimate of the total budget you’ll need.

|

INCOME Record or estimate your annual after-tax income from the following sources. |

||

|

Salary/Wages |

$_________ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Self-employment/Business income |

||

|

Scholarships/Bursaries |

||

|

Parental contributions |

||

|

Other |

||

|

Total Income |

$ |

|

|

EXPENSES Estimate your expenses for the items listed, either as monthly or yearly values. If you are not sure how much to allocate for a given item, it may be helpful to record all your expenses for an entire month before returning to complete this form. |

||

|

Food/Housing |

Dollar Amount |

|

|

Food |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Mortgage/rent |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Other housing costs |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Utilities |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Moving costs |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Other |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Total Food and Housing |

$ |

|

|

Transportation |

Dollar Amount |

|

|

Car payments |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Insurance/license/registration |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Service/repairs/gasoline |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Public transportation/parking |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Other, e.g. car share or ride share |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Total Transportation |

$ |

|

|

Education |

Dollar Amount |

|

|

Tuition |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Books/subscriptions |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Exam fees |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Professional fees |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Other |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Total Education |

$ |

|

|

Investment and Savings |

Dollar Amount |

|

|

RRSP contributions |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Other |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Total Investments and Savings |

$ |

|

|

Lifestyle/Loans |

Dollar Amount |

|

|

Loan payments |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Government student loan payments |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Insurance |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Uninsured health services |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Clothing/dry cleaning/grooming |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Leisure activities |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Child care |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Travel |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Other |

$ |

Monthly/Annually |

|

Total Lifestyle/Loans |

$ |

|

|

Total Expenses |

$ |

|