CHAPTER FOUR

Teaching Teenagers

Guidelines for Teens Thirteen to Seventeen Years Old

THE TEENAGE YEARS are a time of transition from carefree childhood to the adult world of responsibilities, including financial responsibilities. Ideally, you have been teaching your kids about money all along, beginning in elementary school and progressing as they entered middle school. But what if you haven’t — is it too late? No, it’s never too late to learn the basics of earn, save, spend, share, and invest. But this is a crucial time for your teen to develop sound money management skills. As parents, you must lead by example — like it or not, you are financial role models!

It can be difficult to communicate with your teenager about anything at this age, but when it comes to money, try not to make it a taboo subject in your home.

Your kid will learn best if you can manage to be open and adopt a positive attitude to discussing money. Be prepared to answer your teen’s questions and speak to them as equals. Don’t bore them with lectures — and always try to maintain your sense of humour!

|

Family Discussion Money |

|

You may want to initiate the conversation about money with some open-ended questions: • What does money mean to you? • What does it mean to have a lot of money? • How much is a lot of money? • What happens when you cannot pay back what you owe? |

Earn

Their First Real Job

Up until now, your kids have earned money by receiving an allowance, from birthday gifts, or as payment for doing odd jobs. Adolescence is usually the time when they get their first real job, earning money by working part-time during the year or full-time in the summer. Your teenagers may work in a retail store, selling clothes, or at a fast food or other restaurant. Unlike the odd jobs they worked in the past, these jobs will require them to have a Social Insurance Number (SIN), so they can be paid, and a bank account (if they don’t already have one). For the first time they will have a boss, co-workers, and shifts — in other words, a lot more responsibility.

You want your teen’s first real job to be a positive experience for them. They will need your support as they make the transition from being dependent on you for money to making their own. Motivation is the key to a teenager’s initiation to the working world. Encourage them to adopt a positive attitude toward work at a young age so they develop a strong work ethic. You are a role model in this area too, so be aware of your own attitude toward work. Do you wake up energized and excited to get to work, or do you experience a sense of dread at the thought of another workweek? Whether you realize it or not, they probably know how you really feel about your work.

It can be difficult for teenagers to find jobs because they usually don’t have much work experience. They need to be determined and motivated when looking, and they’ll need your support in their job search and your guidance in their choice of a job. Most jobs have minimum age requirements of fifteen or sixteen years. Some teens will be able to handle a part-time job during the school year and still get good grades; for others it may be too much — only you know what’s right for your teen.

|

Things to Do Getting a Job |

|

Once your teen has decided to get a job, you can help by suggesting the following steps: 1. Apply for a Social Insurance Number. • Go to www.sdc.gc.ca and allow six weeks for the application to be processed. 2. Know what you’re good at and what you want to do. • Look for jobs that will allow you to use your strengths and skills. You can discover your strengths by using an online 3. Start the job search. • Prepare a resume and cover letter (most teens get help with this in their careers class at school). • Use your network and online job boards to find opportunities, and don’t be afraid to promote yourself. • Walk around your neighbourhood or local mall and ask store owners or managers if they’re hiring. 4. Prepare for the interview. • Try to present yourself with confidence. • Dress appropriately. 5. Follow up. • Make sure your outgoing voice mail sounds professional. • Send out thank you emails. • Check in after a week if you haven’t heard back. |

Helping Them Understand Their Paycheque

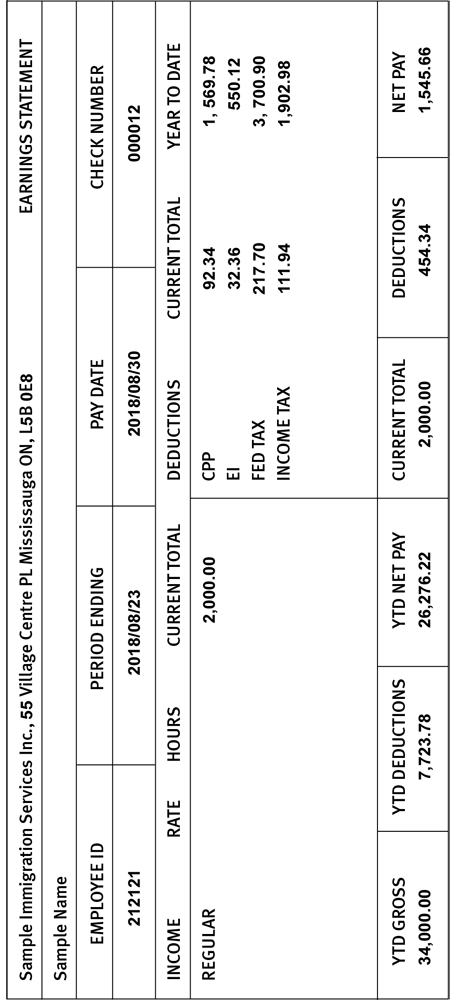

The first paycheque can be very exciting for your teen! It’s worth taking a few minutes to go over the pay stub your teen receives with his cheque so he understands the difference between “gross” and “net” pay. Explain that employers are required by law to make certain deductions or “withholdings” directly from gross pay (the hourly wage or salary) and send these amounts straight to the government. These may include income tax, Employment Insurance (EI), and Canada Pension Plan (CPP) contributions. As a result, your kid’s “net” or take-home pay may be quite a bit lower than they were expecting.

You may want to explain that in Canada we pay tax at graduated rates, meaning that the tax rate goes up as your income rises. Also, we pay income tax to both the federal and provincial governments. There is a tax credit called the Basic Personal Amount ($12,069 for the 2019 tax year). If your teen earns this amount or less in a year, their earnings are not subject to federal tax and generally no tax should be withheld at source.

They may be baffled by CPP and EI. Simply explain that they are programs run by the government, and every person who works must contribute to them. CPP pays benefits to seniors who qualify, and EI protects workers by paying out benefits to those who become unemployed. Make sure they know that their employer also contributes to EI and CPP on their behalf. (See Sample Paystub on the next page.)

Paying for Good Grades

Some parents find it very difficult to motivate their kids to study. Out of frustration and desperation, they may be tempted to “bribe” their kids to get good grades. But this may give kids the wrong idea — that everything has a price and that they should be paid for every accomplishment. At this early stage, it’s better to try to help teens find some intrinsic motivation, some drive within themselves to do their best. Focus on their strengths and the subjects they’re good at. Success in these areas becomes self-reinforcing. You can also remind them that learning good study habits, like learning good money habits, will serve them well as they progress through school and hopefully on to higher learning.

“In our family, my parents rewarded us with ‘bonuses’ when we made the honour roll at school. But rather than give us the money, they put our bonuses into an RESP to encourage and motivate us to go to university.”

Online Consignment Sales

Do people still hold garage sales? It seems like anyone with anything to sell these days does it online using eBay, Craigslist, Kijiji, or social media sites. Looking around your house, you probably have lots of items that are perfectly good but are no longer useful to your family. Consider having your teen sell some of those items online. Remember the Three Cs we introduced in Chapter One — create, conserve, convert? Well, this is a great example of convert. Think of it as a consignment sale. They are selling items on your behalf and as a result are entitled to keep a portion of the proceeds of sale. Whether you split the proceeds fifty-fifty or some other way is entirely up to you and your teen — and it will be a good test of their negotiating skills! It’s a win-win proposition — the more they are able to get for the item, the more you both make.

“My son is sixteen and has been playing guitar since he was nine. We bought him his first electric guitar as a birthday gift, and for a long time it was suitable for his skill level. But as he progressed, he really wanted a better guitar. He did some research to figure out what he wanted to buy and what it would cost. Then we sat down to figure out how we were going to pay for it. My son came up with his own version of the Three Cs: he would create wealth by doing extra chores, he would conserve his allowance by spending less on snacks after school, and he would convert his old guitar into cash by selling it to a buyer he found online!”

Save

Is Cash Still King?

The expression “cash is king” is still conceptually valid in today’s digital world, even if it’s not literally true. It applies equally to businesses and to individuals. When you have cash or other financial resources, you are in command and you call the shots. You have the resources to ride out difficult times, and you also have the capital to take advantage of opportunities that arise. On the other hand, being in debt is like being enslaved. The interest you carry on the debt combined with the debt itself is like an albatross around your neck. (As we discussed in Chapter One, not all debt is bad. There is such a thing as good debt, i.e., debt incurred for the purpose of acquiring an asset that has the potential to go up in value, such as your house or other investments.)

The best place for your teen to save money is in the bank. Almost every teenager should have his or her own bank account. If your child expresses interest (pun intended), you can make sure they understand that the way a bank makes money is by earning a “spread.” The interest rate they pay you on your savings is lower than the interest rate they charge on amounts that their customers borrow.

Help your teen to determine what type of account is best for them (chequing or savings). Investigate whether they still qualify for a youth account, as most fees are waived. At this stage, you can assume that your teen will be accessing the ATM on her own. Remind her that ATMs found in restaurants and most convenience stores charge very high fees. A $20 withdrawal may end up costing her $2.50 to $4 in fees. Encourage her to plan her cash needs ahead of time and use an ATM owned by her bank, where withdrawals are often free.

Of course, teenagers can’t apply for credit cards until they reach the age of majority, which is either eighteen or nineteen, depending on their province of residence. However, they can benefit from learning about the responsible use of credit cards. We will revisit this topic in Chapter Five.

Digital and Cryptocurrencies

In Chapter Two, we introduced the concept of money as a medium of exchange, with banknotes and coins as examples of physical currency that younger kids could understand. Digital currency (also known as digital or electronic money) is another type of currency that has become much more prevalent, and which your teenagers are sure to encounter. Digital currencies are similar to physical currencies, but they can also allow for instantaneous, frictionless, and borderless transactions; they don’t go through a central authority like the government or a central bank.

Cryptocurrencies are a type of digital currency, with Bitcoin being the best known and the largest. If your teens are interested in understanding Bitcoin, you can explain that it uses strong cryptography (hence the name) to secure financial transactions, controls the creation of additional units, and fluctuates in value. Transactions are recorded in a decentralized ledger (the blockchain) that is public and contains records of each and every transaction that takes place. Bitcoin isn’t backed by the government.

Using Personal Values to Set SMART10 Goals

In Chapter One, we introduced the idea of using your values to set meaningful goals. Values are the things in life that are most important to you, that you are willing to take a stand for. You can get a sense of what people value by the way they dress, how they spend their money, or how they interact with others. Values are intangible, but they are not invisible to others. You may think your kids will absorb your values about money by osmosis, be they power, friendship, connection, adventure, fun or security. But as we suggested in Chapter One, kids are exposed to a lot of conflicting messages about money, so it’s important to be clear and explicit about your family values and how they impact your financial decisions. If they haven’t done it already, get your kids to try the Values Validator at the end of Chapter One. Their values will help them prioritize their spending and set SMART savings goals.

|

Family Discussion Goal Setting |

|

Discuss SMART goals with your kids. They are: • Specific • Measurable • Attainable and Action-oriented • Realistic • Timely |

When Emma Taylor completed the Values Validator, she determined that her top five values were adventure, friendship, health, academics, and security. She focused on adventure, doing new and interesting things, and developed a very meaningful SMART goal for herself. Here is Emma’s goal-setting worksheet.

Emma Taylor’s Goal-Setting Worksheet11

|

Top 5 Values |

Top 5 Financial |

Make Specific, |

48-Hour Plan What actions |

Enlist Help Who will |

Time Frame When will |

|

Adventure |

Save up |

$3,000 will be |

Go online and |

Speak to my Discuss |

In two years, |

|

Friendship |

|||||

|

Health |

|||||

|

Academics |

|||||

|

Security |

For another example of a goal-setting worksheet, please see the Resources at the end of this chapter and online at cpacanada.ca/moneysmartkids.

Paying Themselves First — and Making It Automatic

Living within your means is arguably the most important lesson you can teach your kids. And the best way to teach it is to put your money where your mouth is: don’t spend more than you make. Easier said than done, right? Wrong! You can make sure you don’t spend more than you make by paying yourself first. And this is exactly what your teenager should be doing with the money he makes, too.

Every month, he should take a certain amount of money directly from his earnings and put it into savings. A rule of thumb is to save 10 percent of what you earn. If that seems like too much at first, then begin with 5 percent. If 10 percent is easily achieved, then increase it to 15 or 20 percent. To make sure it happens, have him set it up as an automatic transfer. Save him from himself — he will able to spend only what remains. Having a SMART goal that he’s saving for, one that ties back to his values, will make saving meaningful and rewarding and will increase his chances of success.

Spend

Once your kids hit the teen years, they tend to want to spend all their time with their friends. Many teenagers enjoy going shopping and hanging out at the mall or downtown. Sometimes it even feels like they go out of their way to avoid you! You don’t have as many teachable moments as you did when they were younger, when they would accompany you to the grocery store or the mall. They are much more interested in the opinions of their friends (in real life and on social media) when it comes to consuming, but they are also better able to assert their individuality than they were just a few years earlier. However, as long as they are still living under your roof, you can find the right time to instill good spending habits.

Allowance: Increased Financial Responsibility

Whether your teen is working or not, they may still need an allowance. But use it to begin gradually transferring more financial responsibilities to them. They can use the allowance to cover their basic needs and some of their wants. As we will discuss under Budgeting, the budget should be the basis for determining their allowance, which should be given to your teen regularly — weekly, biweekly, or monthly.

As with your younger children, you may choose to use an app to pay your child’s allowance. Anything that’s easy for you to set up and use, and that is also engaging and informative for your teens, is worth trying.

If your teen is also working, should they be allowed to spend the money they earn however they want? Teens want to be independent, and you should let them make their own money choices and live with the consequences. But first give them some guidance and support or they are liable to make some unwise decisions.

Budgeting

Teens may not have much overhead if they live at home because you’re still taking care of most of their needs. As a result, they may not know what their lives really cost. A mistake that teenagers often make, especially if they don’t have savings goals, is to use all their income on discretionary spending.

There is no shortage of items tempting your teen to spend their money: video games, electronics, clothes, shoes, junk food, concerts, etc. These temptations can be difficult to resist at any age. While kids can technically get away with blowing their money at this age, it establishes a bad habit that may be hard to break once they get older and they do have to worry about rent, food, transportation, and utilities — all the mundane essentials.

As we mentioned in Chapter Three, it’s a good idea to regularly review the budget with your teen to see if it needs fine-tuning. The review process also ensures that she feels accountable for staying within budget, and it can provide an explanation as to why she was under or over budget. Just like in the “real world,” things will come up from time to time, and your teen may decide she wants to rob Peter to pay Paul. In other words, she wants to redirect funds from one budget category to another. That’s fine — all budgets are flexible — as long as she does it intentionally and can account for it. See the Teen Budget Template at the end of this chapter.

|

Things to Do Budget |

|

Discuss SMART goals with your kids. They are: • Work with your teen to create a budget. (If your kid has been budgeting from a younger age, all the better!) • Calculate a reasonable amount for their cell phone, transportation, and clothing, being careful to hold your ground on needs versus wants. • Work out an entertainment budget by figuring out how many movies or dinners are reasonable per month. • Have your kid save receipts so she can keep track of what she spends and you can review the details. |

Especially with teens, it’s important to let them make mistakes and learn their lessons. Although the stakes are higher than they were at a younger age, we’re still not talking about thousand-dollar mistakes. Letting them waste their money on something they don’t need, or that’s of low quality, can teach them a lot about value, but only if you take the time to discuss it.

“My sixteen-year-old daughter went through a ‘Starbucks phase’ where she was stopping often on her way home from school and buying fancy, expensive coffees. She didn’t realize how these little purchases were adding up. When the weekend rolled around, she made plans with her friends to see a movie. But as she got ready to go, she checked her wallet and realized she had spent most of her money and didn’t have enough to see a movie. She wanted me to give her the shortfall, but I wouldn’t. I wanted her to learn that when you make choices about how to spend your money, you have to live with the consequences — even if it meant ‘ruining’ her social life.”

Tracking Spending

In Chapter One, we explained why it’s so important for you to track spending: it’s the only way to find out where your money is really going, and it makes you more aware of your spending habits. It’s a great reality check for your kid, too. They often think they’re spending according to the plan — until they face the numbers and see that their tracking shows a very different spending pattern! And as with all of us, being more mindful of their spending can motivate them to make better spending choices going forward.

The Taylors used the jar system to teach Emma to track her spending. She no longer had a piggy bank, of course, but she had three jars in her room labelled “clothing,” “entertainment,” and “transportation.” Emma would allocate her budget to each of the three categories. As she spent money from the jar, she would replace the money spent with a receipt. She could see quite easily how much money was left in her budget in each category at any time. When she got to the end of the money in a jar, she could no longer spend in that category, unless she chose to take it from a different category.

But there’s a whole world of ways for your kids to spend money without using cash. Digital payment systems, like PayPal and Interac e-Transfer, let them send, request, and receive money, and Apple Pay allows them to make purchases in stores, in apps, and on the web. As discussed in Chapter Three, when your kids pay for things by card or phone, rather than using cold, hard cash, they feel less of a sting and assign less value to a purchase.

Digital Tools

Although the Taylors used a very low-tech system with Emma, because she was mostly spending cash, as we move toward a more cashless world, the tools we use need to keep pace. There are lots of different apps that can help your teen manage their finances, including the mobile banking app from your teen’s bank. In addition to letting them view account balances, pay bills, or transfer money, the app also contains tools to track spending by category and create budgets. You can also set up real-time spending notifications that let you know if you’re spending more or less than usual. So even if your teen is not using cash, getting a spending notification will make it more vivid and will help them feel like they’re spending real money. Apps may appeal to teens who are already using their phones to do just about everything else.

In addition to monitoring spending, many apps contain tools that allow your teen to set goals and monitor their progress toward achieving them. Using mobile banking to manage their money and monitor their finances is a good habit for your teen to get into early.

Needs versus Wants Again

During the teenage years, your kid may start to develop a sense of entitlement, demanding the very latest shoes, clothes, cell phones, and laptops. Just like younger kids, teens need to be reminded of the difference between needs and wants. Remind them to ask themselves that all-important question: Do I need it, or would it just be nice to have? Help them understand that they have to take their resources (time and money) into account when making purchasing decisions.

Raising money-smart kids in a world that stresses instant gratification and consumption can be challenging. Social media and “FOMO” (the fear of missing out) are the new peer pressure, and even kids feel like they have to spend to keep up appearances online of “living their best life.”

It can be shocking to see how sophisticated some teens’ tastes are and to watch them covet certain brands. This can be an opportunity to talk to them about marketing and branding. Show them that companies spend a lot of money marketing their products to convince you that you “need” them. Teens are subject to as much, if not more, media and advertising than younger kids. As parents, you can help your teen think critically and skeptically about the messages they get.

Studies are showing that spending too much time on Instagram and other social media and making upward social comparisons can really hurt your kids. Comparing, coveting, and competing with their peers can lead to feelings of envy, bad moods, and dissatisfaction with life. It increases stress levels. It can also lower self-control, which may lead to overspending.

For these and other reasons, you may want to implement some restrictions around cell phone use. In some households, phones are turned off at 9:00 p.m., not stored overnight in bedrooms, and forbidden during family meals. There are also screen-free periods on the weekend so kids can focus on other activities. Once again, you should lead by example and try to follow similar rules.

|

Family Discussion Needs versus Wants |

|

Help your teen assess the relative cost of a “want” by asking them: • How many hours would you have to work to be able to buy it? • Does that feel reasonable? • What are you giving up by spending your money in that way? |

“I get really excited if I’m about to buy something new, but after I buy it, it never makes me as happy as I think it’s going to.”

A Sustainable Approach to Financial Responsibility

Compared to younger kids, teenagers seem to be more aware of, and more concerned about, the impact their consumption has on the environment. You can use this concern to guide them. For example, remind them that constantly demanding new and improved things takes its toll on the environment; excessive, unnecessary driving causes pollution; and being careless by leaving lights on wastes electricity. You don’t want to become a nag, but helping them develop a mindset of sustainability may moderate their consumption habits and lead them to make more responsible choices that are respectful of the environment.

Spending Wisely

Even though teens (hopefully!) have more maturity and self-discipline than younger kids, their brains are still developing, and they still often tend to act on impulse — but you can help. Encourage your teen to shop around and compare prices as a way to stretch their budget and get more for their hard-earned money. Help them look for coupons, sales, or promotions. Let them see how much they can save by taking a patient and disciplined approach to shopping.

“Money was tight in my family when I was growing up. At Christmastime, my mom used to give my siblings and me each $10. She told us to use the $10 to buy a Christmas gift for each member of the family. $10 isn’t a lot of money, so you really had to shop wisely to stretch your budget. This was a very good skill to learn.”

Stored Value Cards

Because they can be difficult to shop for, teens tend to get stored value cards, like gift cards, as presents. Teach them to read the fine print: some gift cards have expiry dates. Also, the cards tend to get forgotten in the back of their wallets unless kids are proactive about using them. Get them to make a list of all the gift cards they have and their remaining balances and to make a plan to spend them before they expire. And remind them that the cards are usually not replaceable, so they should be sure to keep them in a place where they will not lose them.

“When my kids, ages eight and thirteen, get gift cards for their birthdays, I buy the gift cards off them and give them cash instead. And I make them save half. If they had their way, they would use their gifts cards immediately to buy toys or video games that they don’t really need. But then it feels like free money, not real money, and my kids don’t respect it as much. Easy come, easy go.”

Negotiating and Bargaining

In some places in the world, negotiating and bargaining when making purchases is the norm — in fact, it’s expected. Not so in Canada. In most retail stores, especially large chains, the price as displayed is the price you pay at the cash, unless it’s on sale. However, at smaller boutiques, you may be able to get a discount if you ask. It always pays to ask whether the price displayed is actually the best price available.

And don’t forget to tell your teen to budget for sales tax when buying something. Some may not realize that taxes are not normally included in the price of goods but are additional costs. In some provinces, the total sales tax can be as high as 15 percent.

Tipping

Next time you are out for dinner with your teen, talk to them about tipping. They may already know about it, but if they don’t, it’s pretty certain they’ll need to know before too long— they’ll soon be going out to eat on their own with friends. They may not know that servers rely on tips because their hourly wage is very low. You can teach them that the tip is calculated on the total before tax and is usually 15–20 percent for good to excellent service.

Many restaurants, and even takeout food and coffee shops, have tipping built into their point of sales terminals. Often, the suggested tip will start at 18 percent and will be calculated automatically on top of the sales tax. Remind your teen that they can always choose to tip a lower amount or to not tip at all, especially on takeout.

Share

Raising Money at School

Wander the halls of your teenager’s school and you will see flyers announcing Terry Fox runs, WE events, United Way bake sales — you name it! Schools encourage their student bodies to get involved in fundraising and donating money to causes that they’re passionate about. The school wants to foster a sense of community and the satisfaction involved when you give back, and many students spend time volunteering for community service projects as well.

If your teen connects with one of the fundraising projects going on at school, encourage him to get involved. But if nothing resonates with him, then perhaps he could establish a new fundraising initiative at the school by speaking to a teacher or the vice-principal.

“One of the most successful and popular fundraising events at my school was Faculty Follies. We approached three well-known and well-liked teachers at our school, and we asked them to participate. Their role was to commit to do something outrageous, like grow a moustache and dye it pink, dress up as a Star Wars character, or shave their head. Then we set up three large jars and asked students to contribute spare change toward the outrageous act that they most wanted to see. There were no costs involved, so we were able to donate 100 percent of the proceeds to charity. The ‘winning’ teacher had to dress up like Darth Vader and teach all of his classes in a Star Wars costume!”

Raising Money for School

Sometimes, the beneficiary of the school’s fundraising efforts is the school itself. Schools have budgets too, and there never seems to be enough money to go around. Our public schools are funded by the government, but the cutbacks in recent years have left schools scrambling to make ends meet. Rather than make further cuts to programs, schools often establish foundations and have fundraising campaigns.

“Last fall, my son’s high school had an unusual fundraiser. Rather than the typical fun fair, they held an event called 24-Hour Survival. Each student had to raise at least $25 for the chance to spend twenty-four hours camping out on the back field of the school! The field was divided into ‘girls’ camp’ and ‘boys’ camp.’ They brought portable camping stoves so they could cook their meals, and they slept in tents. (Our son begged us to deliver a pizza to his tent!) The event was sanctioned by the school and supervised by school staff. It was definitely one of the highlights of his school year!”

Invest

Investing for Short- and Medium-Term Goals

Most teenagers don’t have a lot of money to invest. Whatever money they’re not spending on immediate purchases, they are probably just stashing in a savings account to spend at a later date. But as they start to develop longer-term goals, they need to understand the relationship between goals and investments, as well as some investing basics. Help them understand that their goals or investment objectives, the length of time they have to reach their goals (investment time horizon), and their appetite for taking risks (risk tolerance) will determine what type of investment is appropriate in the circumstances. We will cover this in more detail in Chapter Five.

A short-term goal means you will need the money in a few weeks or a few months (say to buy a gift) and a bank account is generally the most appropriate savings vehicle. You will earn a low rate of interest, but the funds are 100 percent safe and liquid, meaning easily cashable. Short of the bank collapsing, you will always be able to get your money when you need it.

With a medium-term goal, say one to five years, you have more investment options. You can purchase a term deposit or Guaranteed Investment Certificate (GIC) at the bank with a term that matches your goal. The longer the term, the longer the money is locked in and the more interest you will earn; also, the interest rates on term deposits and GICs are higher than the interest rates on savings accounts. The interest earned will encourage your child to save, as it helps them reach their goal faster. The fact that a GIC cannot normally be cashed in before it matures reinforces the concept of delayed gratification.

Say your fifteen-year-old son has saved a substantial amount over the years (from birthday money, holiday gifts, babysitting, odd jobs, etc.) and is saving for his first year in residence at university in three years. He could purchase a three-year term deposit or GIC with a fixed rate of interest, compounded annually. He will know exactly what he will earn, assuming he holds the GIC until maturity. Again, the principal is guaranteed, so there is no way he can lose his investment. But the funds are frozen for this three-year period, and penalties apply if the investment is cashed before the maturity date.

A longer-term goal requires different planning. You can choose investments with growth potential. Because you have a much longer time horizon, you can take advantage of time and let compounding work for you. With these criteria, you have many more investment options available, which we will cover in Chapter Five.

“I taught my teenager about the ‘Rule of 72.’ It’s a simple formula that tells you how long it will take to double your money with compound interest. Divide the number seventy-two by the interest rate you earn each year. For example, if you have $1,000 invested at 6 percent compounded annually, divide seventy-two by six to get twelve. You will double your money in twelve years.”

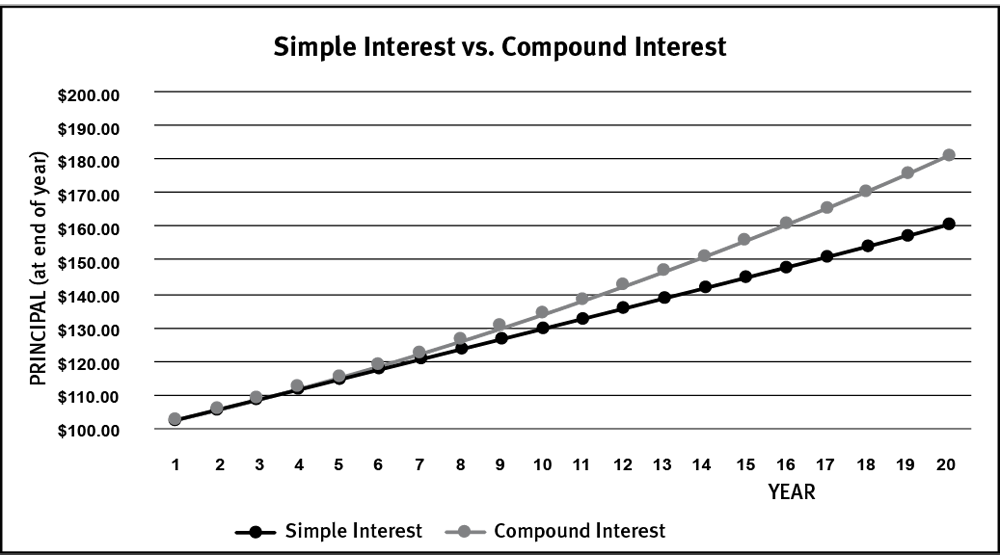

Simple versus Compound Interest

Simple interest is when the bank pays you a stated rate of interest for a stated period of time on your original deposit, which is called the principal. Let’s say the bank is offering a savings account at 3 percent simple interest, and you deposit $100. Once a year, the bank will pay you 3 percent of $100, or $3, and add it to the balance in your savings account. After one year, your balance would be $103. At the end of the second year, you would earn an additional $3 of interest and your balance would be $106. After ten years, you would have earned $30 of interest and have a balance of $130. After twenty years, you would have $160.

Compound interest is when you earn interest on your interest. The magic of compound interest is that it allows your savings to grow much more quickly. Let’s say the bank is offering a savings account at 3 percent interest compounded annually. This means that the interest you earn each year is added to your principal and becomes the new basis for calculating the following year’s interest. As in the example above, you receive $3 in the first year, so at the end of the year you have $103. But here’s the difference: at the end of the second year, interest is calculated at 3% of $103, so you now earn $3.09, giving you a balance of $106.09. After ten years, you would have earned $34.39 and would have a balance of $134.39 versus $130 with simple interest. After twenty years, you would have $180.61 — that’s $20.61 more than you would have earned with simple interest.

When you are earning a higher interest rate and have a longer period of time to invest, compounding can make a huge difference. That’s why it’s so important for kids to develop good saving habits early — to take full advantage of the power of compounding and let their money work for them, rather than the other way around.

This is also a good time to explain that compound interest is a double-edged sword. It’s great when you’re a saver and it’s working for you. But if you’re a borrower, it works just as hard against you. Interest on debt compounds quickly and becomes quite burdensome, especially when interest rates are very high, as they are on credit card balances. (See Simple Interest versus Compound Interest chart below.)

Key Points

• Your kid’s first real job presents a great opportunity to introduce them to the working world — going over their first pay stub with them and explaining about income tax, CPP, and EI teaches a lot about how our society works.

• Teens are not too young to set meaningful financial goals; the clearer their goals, the more likely they are to achieve them.

• School-sponsored programs can be a good opportunity for kids to learn about giving back. Sometimes they can even initiate a charitable program and get the school to endorse it.

• Some teens may be interested in learning some of the basic concepts of investing; the sooner they learn them, the better prepared they’ll be when they actually have money to invest.

Chapter Four Resources

Monthly Budget for Teens

This worksheet can be downloaded at cpacanada.ca/flworksheets

|

Category |

Monthly Budget |

Actual Amount |

Difference |

|

INCOME |

Estimate Your Income |

Your Actual Income |

|

|

Wages/Income Paycheque, allowance, birthday money, etc. |

|||

|

Interest/Income From savings account |

|||

|

INCOME SUBTOTAL |

|||

|

EXPENSES |

Estimate Your Expenses |

Your Actual Expenses |

|

|

Savings Savings account |

|||

|

Bills Taxes — from paycheque |

|||

|

Food/snacks |

|||

|

Transportation |

|||

|

Clothing and other shopping |

|||

|

Cell phone |

|||

|

Entertainment (e.g., movies, restaurants, video games, music) |

|||

|

EXPENSES SUBTOTAL |

|||

|

NET INCOME |

Goal-Setting Worksheet12

This worksheet can be downloaded at cpacanada.ca/flworksheets

|

Top 5 Values |

Top 5 Financial |

Make Specific, |

48-Hour Plan What actions |

Enlist Help Who will |

Time Frame When will |

|

Example: |

Increase |

Increase |

Call benefits |

Call Pete |

In two |

|

Family |

|||||

|

Self- self- |

|||||

|

Community |