Chapter 12

1 John 4:7–16

Literary Context

John has restated in distinctive Christian form the first and second greatest commandments, love for God and love for neighbor (cf. Matt 22:37–40; Mark 12:30–31; Luke 10:27). In 3:23 he writes, “And this is [God’s] command: to believe in the name of his Son, Jesus Christ, and to love one another.” In 4:1–6 he has further discussed what it means to believe in Jesus Christ as the one who “has come in flesh.” Now John turns the reader’s attention to the second restated commandment, the command to love one another. Notice the repetition of “love one another” (ἀγαπῶμεν ἀλλήλους) in 3:23 and 4:7, and note that the Spirit is given as the basis of assurance of remaining in him in both 3:24 and 4:13. This extended discussion about love spans 4:1–21 and elaborates on the relationship between love for one another and the love of God, both his for us and ours for him.

- XI. The Spirit of Truth Must Be Discerned from the Spirit of Error (4:1–6)

- XII. God’s Love Expressed (4:7–16)

- A. The Command to Love One Another (4:7–10)

- B. The Command to Love One Another Restated (4:11–14)

- C. Confession That “Jesus Is the Son” Is Necessary for One to Remain in God (4:15–16)

- XIII. God’s Love Perfected in the Believer (4:17–5:3)

Main Idea

John here identifies both the source and definition of love as God himself. God’s love is most supremely expressed in the sending of the Son as an atoning sacrifice for our sin so that we might live eternally through him.

Translation

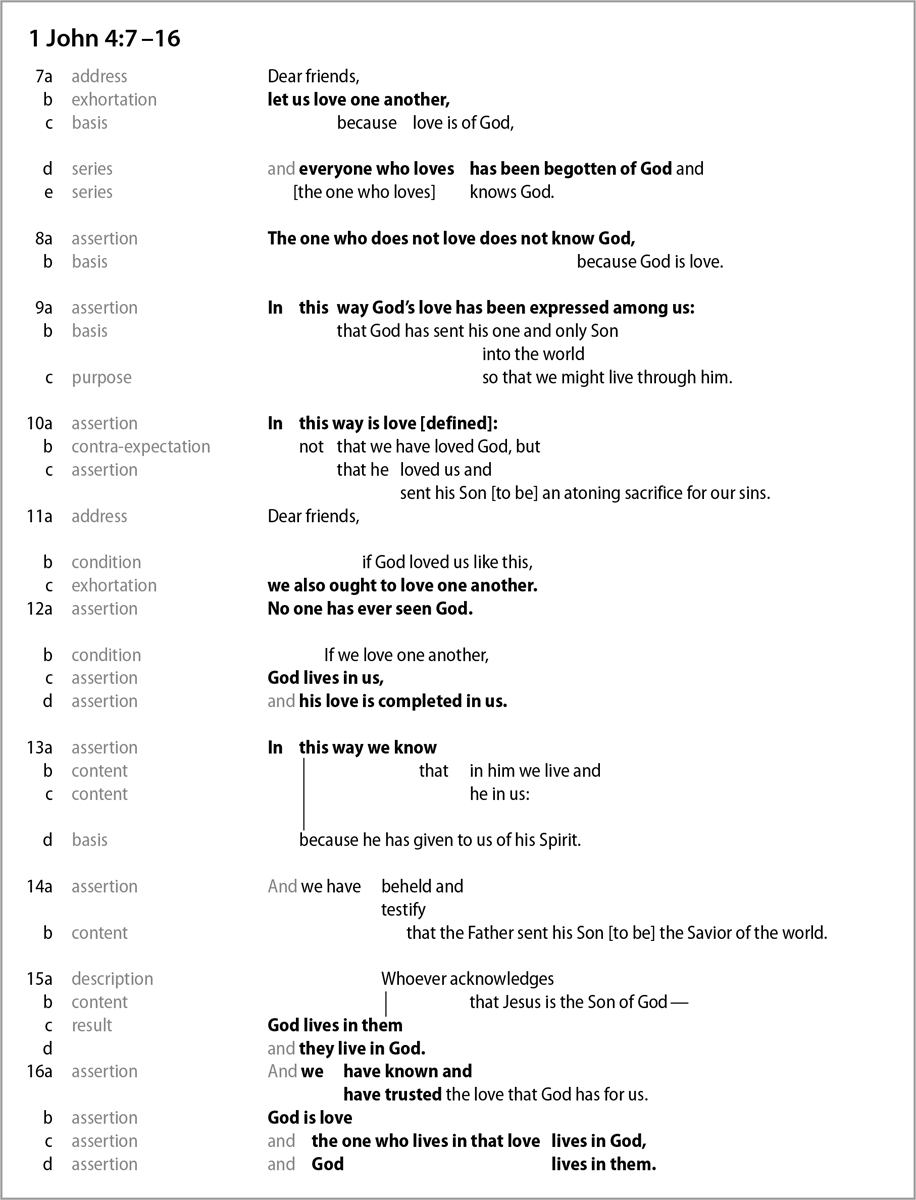

Structure

This passage continues the discussion begun in 4:1 (“Dear friends, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits …”), a discussion that will continue through to 4:21 (“the one who loves God must also love their brother or sister”). This passage contributes to the larger discussion by providing a visible criterion by which those who are of God may be identified. John here resumes the question of discernment raised in 4:1–2 by pointing out that those who have been given the Spirit of God (4:13) are those who have received God’s love through faith in Jesus Christ, who has come in the flesh (4:2). Because the sending of God’s Son in the flesh as an atoning sacrifice (4:10) is the definitive expression of God’s love, those who have received and benefited from the Father’s love will, by virtue of their spiritual relationship to the Father, manifest that love for others in their lives.

John’s continued argument here has two parts, 4:7–10 and 4:11–14, each prefaced by the vocative “dear friends” (ἀγαπητοί). The major exhortation of this passage is expressed twice; first in 4:7 with the hortatory subjunctive, “dear friends, let us love one another,” and second in 4:11, “dear friends … we also ought to love one another,” considering how God has loved us. The first part explains love as the hallmark characteristic of those who have been born of God, who have been given life through the Son whom God sent into the world. It moves from the exhortation to love one another, to the statement that God is love (i.e., defines love), to a discussion of the nature of love that God has defined by sending his Son as an atoning sacrifice.

Verses 9 and 10 are nearly parallel:

Verse 9

- A In this way God’s love has been expressed among us:

- B that God sent his one and only Son into the world

- C so that we might live through him.

- B that God sent his one and only Son into the world

Verse 10

- A´ In this way is love [defined]: …

- (not that we loved God, but that he loved us)

- B´ and sent his Son

- C´ to be an atoning sacrifice for our sins.

The second part of the passage explains that only as Christians express love for one another as God defines it, is God’s love made evident and visible and only then is it in fact perfected among his people. Such expression of love for one another is therefore the evidence of remaining in him and of having been given God’s Spirit. Only those who exhibit this love are qualified to testify to the supreme act of God’s love, the sending of his Son as Savior of the world. Therefore, the testimony of those who do not exhibit such love for fellow believers should not be received (cf. 2:19). As Moberly points out, “This love enables critical discernment to take place.”1 A similar role of love in spiritual discernment is found with Paul’s famous love chapter (1 Cor 13) located within the discussion of the discernment of spiritual gifts (1 Cor 12).

These two segments of the argument are sandwiched between the repeated statement that “God is love” (vv. 8b, 16b), which forms the theological foundation of the command to love.

Exegetical Outline

- XII. God’s Love Expressed (4:7–16)

- A. The command to love one another (4:7–10)

- 1. Love is of God (4:7a-c)

- 2. The one who loves (4:7d-e)

- a. has been born of God (4:7d)

- b. knows God (4:7e)

- 3. The one who does not love (4:8)

- a. does not know God (4:8a)

- b. because God is love (4:8b)

- 4. God’s love revealed (4:9–10)

- a. God sent his Son so we might live (4:9)

- b. God’s love defines love (4:10)

- B. The command to love one another restated (4:11–14)

- 1. God’s love is made visible in Christian love for each other (4:11–12c)

- 2. God’s love reaches its intended goal (4:12d)

- 3. God’s Spirit assures us of right relationship with him (4:13)

- 4. The Spirit’s testimony is that the Son is Savior of the world (4:14)

- C. Confession that Jesus is the Son is necessary for one to remain in God (4:15–16)

- 1. The mutual indwelling of the believer and God rests on belief in Jesus as Son of God (4:15)

- 2. “We” who make that confession have known and have believed God’s love expressed in the Son (4:16a)

- 3. God is love (4:16b)

- 4. Remaining in God requires remaining in his love expressed in Christ (4:16c-d)

- A. The command to love one another (4:7–10)

Explanation of the Text

4:7 Dear friends, let us love one another, because love is of God, and everyone who loves has been begotten of God and [the one who loves] knows God (Ἀγαπητοί, ἀγαπῶμεν ἀλλήλους, ὅτι ἡ ἀγάπη ἐκ τοῦ θεοῦ ἐστιν, καὶ πᾶς ὁ ἀγαπῶν ἐκ τοῦ θεοῦ γεγέννηται καὶ γινώσκει τὸν θεόν). John returns yet again to his major exhortation of love for one another. He begins a new unit of exhortation, again addressing his readers as “dear friends” (ἀγαπητοί), the term he uses several times in the context of his remarks about love. Occurring with equal frequency is the term “children” (τεκνία), which most often occurs in discussions involving the fatherhood of God.

The rationale given for the love command is that love is a defining characteristic of God. Therefore, those who have been born of God are also defined by their love for others—like father, like son, as the saying goes. In fact, exhibiting the love characteristic of the Father evidences a personal knowledge of God. In this way, “everyone who loves” is circumscribed. It is not everyone who loves in whatever way pleases him or her who has been born of God, but everyone who loves as God defines love (see comments on 4:8). Note that the verb “has been begotten” (γεγέννηται) is in the perfect tense, denoting that the new birth precedes love and knowledge.

John may be presenting this teaching not only to motivate right relationships within the community, but also to provide a criterion of discernment concerning those who are not truly members of it. Moberly points out that John is concerned to articulate a “critical theological epistemology,” that is, how one can know that they know God, and also to identify those who are not truly a part of the believing community.2 The demonstration of love by those who have received God’s love in Christ continues the discussion of the discernment of spirits begun in 4:1.

4:8 The one who does not love does not know God, because God is love (ὁ μὴ ἀγαπῶν οὐκ ἔγνω τὸν θεόν, ὅτι ὁ θεὸς ἀγάπη ἐστίν). John underscores the relationship between love and knowledge of God, who is love. If everyone who loves has been begotten of God and knows God, the converse is also true: the one who does not love does not know God.

This is the third time John has mentioned the one who does not love (ὁ μὴ ἀγαπῶν). Such a person is not of God (3:10), remains in death (3:14), and here, does not know God. Therefore, such a one does not have eternal life, for the essence of that life is knowledge of God and the one whom he has sent (cf. John 17:3). The failure to love is not simply an ethical failing, but means that one remains in the darkness of sin, apart from salvation. Those who fail to love are outside the Christian community and have no truthful testimony of God, for they have no true knowledge of God. Personal knowledge of God and love for others as God defines it are inseparable. John’s exhortation therefore implicitly demands self-examination.

The statement that “God is love” is one of the best-known verses even among people who are not Bible readers. In John’s letter, it stands alongside the similar statement, “God is light” (1:5). Neither of these statements is an absolute metaphysical maxim about the essence of God’s being,3 but these statements point to God’s authority to define sin in the first instance, and his authority to define sin’s opposite, love, in the second. God’s defining love is best revealed in his salvation of humanity on the cross, for it was love that sent God’s Son into the world to suffer and die (4:10; cf. John 3:16; see “In Depth: ‘Love’ in John’s Letters” at 4:16).

Although this biblical statement is so well known by those outside the Christian church, it is also largely, and sometimes grossly, misunderstood, for love is distorted and misunderstood in our society. Ask someone on the street what love is, and you’re likely to get a variety of answers. “Love is a feeling,” some may say. “Love is a commitment.” “Love is a sexual relationship.” “Love is sharing.” “Love is an orientation.” Or perhaps, “Love is an abstraction that is hard to define, but you’ll know it when you see it.” Proper interpretation requires allowing John to define what he means by love. Proper theology means rooting the definition in God’s authority.

If all the Law and Prophets can be summed up by two commands, to love God and love others as you love yourself, then a biblical definition has to do with right behavior in relationships. How does one express love for God? John tells us that love for God means keeping his commands (5:2; 2 John 6), which involves how we treat one another (1 John 4:20–21). How we treat one another rightly is defined by Jesus’ interpretation of the OT moral law, as given in Matt 5 and his self-giving demonstration of love on the cross. Thus, John presupposes that his message will be read, not using the world’s definitions, but within the context of the greater biblical discussions that define love.

Note that the syntax of the Greek does not permit the terms of the statement to be reversed, as Yarbrough points out:

John does not say that love is God, a statement found nowhere in Scripture. “There have always been some who wished to apotheosize human love, but it cannot be done.”… To do so would be to replace a living, personal, and active God with an intellectual, ethical, volitional, or emotional abstraction. This is the last thing that the language of 1 John, or the graphic portrayal of God incarnate in the Gospels, would permit.4

Furthermore, as Moberly points out,

a theoretical definition of deity in terms of a supreme human quality … can give rise to Feuerbach’s potent critique that the quality is more ultimate than the deity, and that to keep the quality, while disposing of the deity, is to hold firm to the one thing needful.5

This tendency to define God by human concepts of love leads directly to self-serving heresy, such as is often presented by popular spirituality. While being interviewed, a religious talk-show host mentioned a spiritual experience he once had of “what is defined by love, or oneness, or God.”6 He went on, “Ultimately, our faith and deeds give us an experience of love and connectedness. The more good we do, the more experience we have with God, or love.” When asked what was his message to the audience, he replied, “We are all made of love, God is love, and we are God” (emphasis added).7 This is clearly an aberrant understanding of John’s teaching (cf. 4:10).

4:9 In this way God’s love has been expressed among us: that God has sent his one and only Son into the world so that we might live through him (ἐν τούτῳ ἐφανερώθη ἡ ἀγάπη τοῦ θεοῦ ἐν ἡμῖν, ὅτι τὸν υἱὸν αὐτοῦ τὸν μονογενῆ ἀπέσταλκεν ὁ θεὸς εἰς τὸν κόσμον ἵνα ζήσωμεν δι’ αὐτοῦ). John is the NT writer who most clearly explains how God has shown his love for humanity. Both here and in the most famous gospel verse, John 3:16, the sending of his Son to be lifted up on the cross is the supreme expression of God’s love for his fallen creation. God was not obligated to seek and to save any human being, but this was the purpose of the incarnation of Christ. The wonder of God’s grace is that any of us, in our willful, rebellious nature, have received the eternal life that Christ offers because of God’s love (see The Theology of John’s Letters).

The Son is again called the monogenēs (μονογενής) Son (John 1:14, 18; 3:16, 18; cf. Heb 11:17), the unique Son of God (μόνος + γένος). The traditional translation “only begotten” is a theological interpretation introduced by Jerome’s Latin translation. But the original language emphasizes the uniqueness of Christ, not his begottenness. God has many children, both sons and daughters throughout history, but Jesus is not just one of them. He is unique, the monogenēs Son, who was with God and was God (John 1:1). And the good that came from his death was also unique, for his is the only death through which we have been given life (cf. John 17:3).

The uniqueness of Jesus Christ is foundational in Christian theology. Christianity is not based on human sacrifice, for God did not choose one of his human children to be sacrificed on behalf of the others. God’s love in that case could be questioned. But God himself stepped into humanity in the person of Jesus, making Jesus a unique human being, uniquely qualified to pay the penalty for the fallen human race. God himself was willing to be sacrificed on the cross, to experience human life and death; such is his love for us. Therefore, God’s love is not contingent on the circumstances of our lives. Good things may happen; bad things may happen; but God’s constant, eternal love remains unchanged because of the cross, which stands unchangeable throughout all of human history.

4:10 In this way is love [defined]: not that we have loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son [to be] an atoning sacrifice for our sins (ἐν τούτῳ ἐστὶν ἡ ἀγάπη, οὐχ ὅτι ἡμεῖς ἠγαπήκαμεν τὸν θεόν, ἀλλ’ ὅτι αὐτὸς ἠγάπησεν ἡμᾶς καὶ ἀπέστειλεν τὸν υἱὸν αὐτοῦ ἱλασμὸν περὶ τῶν ἁμαρτιῶν ἡμῶν). John must define love as it originates with God and not with human thoughts and emotions. Just as in our times, love was a word in the first century with many different definitions and connotations, so to be sure his readers don’t misunderstand, John defines the love he is talking about. (Note the anaphoric article, referring to love as it was mentioned in vv. 7–9.) Here, John says, is the true origin of love: God himself.

Human history has witnessed many things motivated by love for God, some of them horrendous acts of evil. Even the most pure and well-intentioned “love” for God that has its origin in only human emotions and sentiments is not the kind of love of which John speaks. In 4:8, John has already stated that “God is love,” and in 4:9 that God’s love motivated the incarnation of Jesus Christ, so that “we might live through him.” Here, he restates that true love is the love that originates with God himself, not whatever might pass for love by human origin and definition. The kind of love of which John speaks does not have its origin within the human being but is from God’s Spirit.

In the double accusative “his Son an atoning sacrifice” (τὸν υἱὸν αὐτοῦ ἱλασμόν), hilasmon functions as a predicate nominative.8 God’s love for the human race focuses on the problem of sin and our need for redemption. Although the word translated “atoning sacrifice” (hilasmos) is found in the NT only here and in 1 John 2:2 (see comments there), the cognate verb hilaskomai is found in the LXX, where it means to forgive people their sins (Exod 32:14; Deut 21:8; 2 Kgs 5:18; 24:4; 2 Chr 6:30; Pss 25:11; 65:3; 78:38; 79:9; Lam 3:42). In the NT this verb occurs but twice—in Luke 18:13 and Heb 2:17. In the first case, it is in an appeal to God for forgiveness (ἱλάσθητί μοι); in the second it is in a description of the work of Jesus the high priest, to make atonement for sin.

Forgiveness of sin is at the heart of atonement and is the clearest expression of God’s love. We cannot truly love God or others until we have received God’s redemptive love offered in Christ, the forgiveness of our sin based on the atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ himself (see “In Depth: ‘Love’ in John’s Letters” at 4:16).

Verses 9 and 10 exhibit a parallelism centered on the topic of God’s love (see Structure, above). Commenting on redemption in 1 John, Lyonnet writes:

It can be seen at once, not only how intimately the notion of Christ-hilasmos is connected with the love of God the Father, but also how strictly parallel the statements in v. 9b and v. 10b are, so that the phrase “hilasmos for our sins” accurately corresponds to the phrase “that we may live through him….”9

This is consistent with the use of this word in 2:2. The sending of God’s Son is stated in each verse to be the expression of God’s love. In 4:9, the purpose/result of the sending (hina clause) is that we may live through Christ. In v. 10, the sending of the Son is to be the atoning sacrifice for our sins. The parallel indicates that it is the atonement for sins that achieves God’s loving purpose of eternal life for his people. Genuine, pure human love derives from God’s love, a love that sent the Son to be an atoning sacrifice for our sins. Having received that love from God, a person can then love God and love others truly (see The Theology of John’s Letters).

4:11 Dear friends, if God loved us like this, we also ought to love one another (Ἀγαπητοί, εἰ οὕτως ὁ θεὸς ἠγάπησεν ἡμᾶς, καὶ ἡμεῖς ὀφείλομεν ἀλλήλους ἀγαπᾶν). God’s love for his people forms the basis of our love for one another.

Verse 11 forms a nearly chiastic inclusio with v. 7:

- A Dear friends,

- B let us love one another,

- C because love is of God.

- B let us love one another,

- A´ Dear friends,

- C´ if God loved us like this,

- B´ we also ought to love one another.

The first class condition of fact assumes God’s love for his people as the basis of our love for one another. But if the definition of love is revealed in Christ’s atoning sacrifice of himself on the cross, how can we love one another in any similar way? To answer this question, note that God’s love focused its action on our greatest need, and the achievement of such love secured the reconciliation of our relationship with him. Similarly, our love for others should recognize their needs, and we should seek to maintain a right relationship with them.

Recall Jesus’ discussion of the command to love one’s neighbor as oneself in the parable of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37), in which he defines both “neighbor” and “love.” The command to love is not a demand for forced intimacy or shallow sentimentality. It is a command to meet the needs of others when we encounter them. To act with redemptive love toward others means to forgive those who need our forgiveness, just as God forgave us in Christ. It means to spend our time and money (i.e., lay down our lives) meeting the needs of others. In certain rare and extreme instances, it may mean actually giving our lives so that others may live (see comments on 3:16–18).

4:12 No one has ever seen God. If we love one another, God lives in us, and his love is completed in us (θεὸν οὐδεὶς πώποτε τεθέαται. ἐὰν ἀγαπῶμεν ἀλλήλους, ὁ θεὸς ἐν ἡμῖν μένει καὶ ἡ ἀγάπη αὐτοῦ ἐν ἡμῖν τετελειωμένη ἐστίν). John now reminds his readers of the theme of God’s revelation of himself in Christ by repeating almost verbatim a statement found in John 1:18. In that text, the unique God, the Son Jesus Christ, who is closest to the Father, has made God known. And the center of that revelation of God is his love for fallen human beings that on the cross provided the cure for our fatal sinfulness.

Here in 1 John 4:12, it is the Christians’ love for one another, derived from God’s love for us, that is revelatory. As Lieu points out, “If God is love, it follows that love is a, perhaps the, mode of divine presence.”10 The invisibility of God is a major premise of the Johannine books (cf. John 1:18), but God is revealed in human expression, first and most supremely in Jesus (1:18; 5:37; 6:46), and second in the quality of Christians’ relationships with others.

One might expect the statement “if we love God, then God remains in us,” so it is somewhat surprising to read instead, “if we love one another, God lives in us.” A similar surprise was found in 1:6, where John explains that the one who walks in darkness cannot have fellowship with God. He then states the converse, “But if we walk in the light … we have fellowship with one another …” (italics added), exactly where we would expect to find “fellowship with God” instead.

Because God is invisible in the material world we inhabit, how does one express love for God and have fellowship with him? We can’t hug him or send him a nice Valentine on February 14. Consistently the NT speaks of love for God in terms of relationship with his people, as we gather together for worship, as we pray for one another, as we take Holy Communion together. Although Christianity in North America has a very “Jesus-and-me” quality, the NT writers did not conceive of an independent, maverick Christian (cf. 1 Pet 2:4–5). Even the OT commands that stipulated obedience to God were largely commands concerning how to treat others (Exod 20:12–17; Deut 5:16–21). Biblically defined love for others is our appropriate expression of love for God. When Christians love others as God defines love, God remains in us making his presence known, and his love is completed in us (ἡ ἀγάπη αὐτοῦ ἐν ἡμῖν τετελειωμένη ἐστίν).

Three questions arise here. (1) Does “in us” mean collectively as God’s people (i.e., “among us”) or in each believer individually? (2) Is “his love” (ἡ ἀγάπη αὐτοῦ) objective (i.e., one’s love for God) or subjective (i.e., God’s love for us)? (3) What does it mean that such love “is completed” (τετελειωμένη ἐστίν)? (See further discussion of this verb in comments on 2:5 and 4:17.)

(1) All throughout the NT, the prepositional phrase “in us” (ἐν ἡμῖν) presents a certain ambiguity when it refers to Christian believers. But in many (most? all?) instances, the difference between the collective sense and the individual is not great or significant. Collectively, the Christian church is made up of individual believers, those who have come to like-minded faith in Christ and have been born anew by the Spirit who dwells within them individually. Therefore, because the collective is composed only and exhaustively of the individual believers, there is arguably little difference between “in us” and “among us.”

(2) The answer to the question of whether “his love” is objective11 or subjective12 is found in the way John defines love between God and his people as reciprocal in nature. Some interpreters consider a third sense, taking the genitive as one of quality that refers to God’s kind of love, and then conclude that all three senses are present in this verse.13 That is, we love because God first loved us (4:19, see below). But God has deemed it necessary that we express our love for him in the act of loving other human beings with a love that derives from the kind of love he has shown for us in Christ.

(3) Such love “is completed” (τετελειωμένη ἐστίν), or has been brought to its intended goal and fullest form (note perfect tense), when we love others. It is through human beings that God’s love “finds its fulfilment on earth.”14 If we note that the same verb is used in 2:5 with reference to the love of God, these two verses are mutually interpretive, suggesting a subjective genitive as the answer to the second question. Therefore, John is saying that God’s love for us reaches its intended completion or goal when we in turn express love for others, completing the reciprocity between God and his people.15

4:13 In this way we know that in him we live and he in us: because he has given to us of his Spirit (Ἐν τούτῳ γινώσκομεν ὅτι ἐν αὐτῷ μένομεν καὶ αὐτὸς ἐν ἡμῖν, ὅτι ἐκ τοῦ πνεύματος αὐτοῦ δέδωκεν ἡμῖν). John introduces the role of the Holy Spirit as evidence of God’s presence in the believer’s life. The invocation of the Spirit here is the basis on which a Christian knows that he or she is right with God and shows that Christian love is motivated by the Spirit, not by sentimental human emotion. The next verse concerns the Christian testimony that God sent his Son to be the Savior of the world. This flow of thought closely follows John 17:18–26 (italics added):

- John 17:18: “As you sent me into the world, I have sent them into the world.”

- John 17:21: “ … that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me.”

- John 17:26: “I have made you known to them … in order that the love you have for me may be in them.”

Christian love is the expression of us being in God (who is love) and him in us. That unity also has an evangelistic and revelatory purpose so that the world might see the presence of God’s love in Christ. The Spirit is the assurance of God’s presence in us and us in him. As Kruse asks:

When the author introduces the giving of the Spirit as the ground of assurance in 4:13, is he implying: (a) that the Spirit motivates love for fellow believers and the objective practice of love is the basis of their assurance; or (b) that the Spirit teaches the truth about God’s sending Jesus as the Saviour of the world and knowing this provides believers with the basis of assurance; or (c) that the very presence of the Spirit himself in believers creates the sense of assurance?16

While there may be truth to all three options, the third can be a matter of dispute and is likely to have been involved in the schism mentioned in 2:19. People may sincerely claim to have the Spirit, but what is the objective basis of such a claim, especially when serious differences between professing Christians with the same claim arise?

The first option may be the tangible expression of the Spirit’s presence, but many good people who are not believers can do loving things quite apart from the Spirit’s presence in them.

The second option is likely John’s point, when compared with the similar statement in 3:24, “And the one who keeps his commands remains in him [God], and he himself in them; and in this way we know that he remains in us: from the Spirit, whom he gave to us.” “The one who keeps his commands” corresponds to the exhortation to love one another (see 4:11–12), and both are followed by similar statements, “in this way we know that he remains in us” (3:24; cf. 4:13). The next verse after 3:24 (i.e., 4:1) concerns revelation and the discerning of spirits that led into this discussion about love. How is the Spirit of truth discerned from the spirit of error? The Spirit of truth acknowledges that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh, which is the objective ground of salvation and the basis for reassurance. Therefore, 3:24 and 4:13 form an inclusio and indicate, as Kruse points out,

that the Spirit teaches the truth about God’s sending Jesus as the Saviour of the world and knowing this provides believers with the basis of assurance…. It is neither the very presence of the Spirit nor the activity of the Spirit producing love for fellow believers that the author has in mind here, but rather the Spirit as witness to the truth about Jesus proclaimed by the eyewitnesses.17

The Spirit provides inner testimony of the truth that God’s love is not expressed in some generic spiritual truth, as seems likely the secessionists were teaching, but in the sending of the Son to be the Savior of the world because he is the atoning sacrifice for our sins. Belief in that testimony provides the assurance that one remains in God and he in them.

4:14 And we have beheld and testify that the Father sent his Son [to be] the Savior of the world (καὶ ἡμεῖς τεθεάμεθα καὶ μαρτυροῦμεν ὅτι ὁ πατὴρ ἀπέσταλκεν τὸν υἱὸν σωτῆρα τοῦ κόσμου). With this verse the author returns to his role as a witness by echoing 1:1–4, with which he opened the letter with the topic of the source of authoritative truth about eternal life. This statement affirms that the author considers himself the bearer of spiritual truth, a truth that is not relativized by one’s nationality, ethnicity, or philosophy. Because the Son is the only Savior for all the people of the world (2:1–2), any claim to spiritual truth not based on Christ’s atoning death is false and cannot form the basis of assurance about eternal life.

4:15 Whoever acknowledges that Jesus is the Son of God—God lives in them and they live in God (ὃς ἐὰν ὁμολογήσῃ ὅτι Ἰησοῦς ἐστιν ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ θεοῦ, ὁ θεὸς ἐν αὐτῷ μένει καὶ αὐτὸς ἐν τῷ θεῷ). The subjective presence of love and the Spirit in the believer’s life is brought back to the objective basis of the incarnation of God in Christ. Because love for one another is based on the revelation of God’s love expressed on the cross of Jesus Christ, it is the one who acknowledges that revealed truth who has been reconciled to God. Fellowship with God would not be possible without the historical fact of the incarnation.

However, it is not sufficient to believe in the historical Jesus; one must also believe that the man Jesus was the Son of God whom the Father sent to atone for sin. Mutual indwelling of God in the believer and the believer in God echoes John’s gospel, where the verb “remain” (μένω) occurs dozens of times in reference to the intimate relationship between the three members of the Trinity (e.g., John 1:32, 33; 14:10; 15:10). Believers in Christ have the privilege of entering into a fellowship with God (1 John 1:3; cf. John 12:46; 14:17; 15:4–7). The idea of living or abiding with God stands behind the promise of having a place in the Father’s house, which is a reference to eternal life (John 14:2, 23; see The Theology of John’s Letters).

The chiastic structure gives a memorable quality to the promise:

- ὁ θεὸς ἐν αὐτῷ μένει God in them [sing.] abides

- καὶ αὐτὸς ἐν τῷ θεῷ and they [sing.] abide in God

4:16 And we have known and have trusted the love that God has for us. God is love and the one who lives in that love lives in God, and God lives in them (καὶ ἡμεῖς ἐγνώκαμεν καὶ πεπιστεύκαμεν τὴν ἀγάπην ἣν ἔχει ὁ θεὸς ἐν ἡμῖν. Ὁ θεὸς ἀγάπη ἐστίν, καὶ ὁ μένων ἐν τῇ ἀγάπῃ ἐν τῷ θεῷ μένει καὶ ὁ θεὸς ἐν αὐτῷ μένει). Faith in the atoning death of Jesus Christ is faith in God’s love for us. The one who lives in that atoning love is alive in God. In this statement John brings love, faith, and atonement for sin together in his readers’ thoughts.

Verses 14 and 16 have parallel structures:

|

v. 14 |

καὶ ἡμεῖς τεθεάμεθα καὶ μαρτυροῦμεν A And we have beheld and testify ὅτι ὁ πατὴρ ἀπέσταλκεν τὸν υἱὸν σωτῆρα τοῦ κόσμου B that the Father sent his Son [to be] the Savior of the world. |

|

v. 16 |

καὶ ἡμεῖς ἐγνώκαμεν καὶ πεπιστεύκαμεν A´ And we have known and have trusted τὴν ἀγάπην ἣν ἔχει ὁ θεὸς ἐν ἡμῖν B´ the love that God has for us. |

This parallel reinforces the thought that the sending of the Son as Savior is the expression of God’s love for us. Seeing that truth leads to testifying to it; knowing that truth calls us to trust in it. Only by trusting in God’s atoning love do we have assurance of eternal life in fellowship with God.

John repeats the statement that “God is love,” first mentioned in 4:8b in reference to the one who does not love and therefore does not know God. As Brown observes, the first statement that “God is love” in 4:8 reveals the motive for the sending of the Son, and this second occurrence “stresses the result (divine abiding) in the Christian.”18 Here the statement is the ground for one to remain in that love (note anaphoric article pointing back to 4:8b), and by doing so, remain in God. The one who remains in God’s love, expressed on the cross of Jesus, stands in contrast to “the one who does not love” and thereby demonstrates that they do not know God (4:8a), and that they have not been born of God (4:7). A person’s love—for God and for others—is anchored in the cross of Jesus.

Theology in Application

God, Love, and Sacrifice

Three major points are clear in this passage: (1) God is the only one who has the authority to define what “love” is. (2) God’s love for us is supremely expressed on the cross of Jesus Christ. (3) There can be no genuine love for God or for others that is not anchored in one’s faith in the atoning cross of Jesus. As Jonathan Wilson observes:

As we enter that kingdom [of God], we enter into a salvation that is also the way of love. Love is a terribly debased term today, almost beyond rescue as a description of the good news of the kingdom come in Jesus Christ. However, the New Testament is full of the language of love, particularly as Christ exemplifies God’s love and enables that same love in us. Therefore, we must work to recover an understanding and practice of love.23

Poets write about it, singers sing about, greeting cards convey the sentiment of love. But our world is full of whacky, irresponsible, and even perverse definitions of love that are used to rationalize selfishness, manipulate others, and even give evil free rein in the name of love. Because of our sinful, fallen human nature, we have lost the ability to define, much less practice, love as we were created to do. And so the NT closely associates love for God with morality. As both creator and judge, God gets to define love and to stipulate how it is to be practiced. But his definition is so unlike the world’s that those who prefer their own, more self-serving definition often reject it.

When taken without God’s definition of love, John’s statement that “everyone who loves has been begotten of God and … knows God” (4:7) is inevitably misused to justify just about anything the human heart can imagine, because the world is full of counterfeit love. People attempt to justify illicit romantic relationships and homosexual relationships in the name of a “love” that is defined by merely human emotions and ideas, even as powerful as those may be. Parents and spouses may confuse a need to control with love. Some may attempt to justify euthanasia or abortion by some false definition of love. But love is the opposite of sin, and anything practiced that the Bible defines as sin cannot be authentic love.

The violent death of a man executed as a seditious criminal would be the last place one would expect to see a demonstration of love, but that is exactly where the NT locates it. Such love is not based on human motives or emotions, but finds its impetus in the merciful heart of the creator God, who would rather submit to earthly horrors himself than condemn his beloved human race to perish. The cross of Jesus Christ is God’s love extended across the chasm that stranded us on hell’s side, separated from God and trapped in our sin. There is no other bridge by which we can cross over from death into life (John 5:24). It is only being cleansed from our sin that allows us to be reconciled to God and relate rightly to one another. The word God uses to describe relating rightly to others is “love.”

Is God Loving?

People can experience many horrible things in life, leading both Christians and unbelievers to question God’s love. How could a loving God let such horrible things happen as we see continually in the daily news? Without diminishing the reality of pain and suffering, John’s answer would be that God has already loved each of us to the fullest extent by providing that crossover from death to life. For death is the worst this life can bring against us, but when this life has been swallowed up by eternal life, even the worst is not our defeat. Because God’s fullest love has already been given in Christ more than two thousand years ago, it is not based on what we do or what others do to us. What greater gift of love could God give than freedom from death? (See The Theology of John’s Letters.)

When someone has experienced freedom from sin and freedom from death, they are able to love God and others as God intended. This is because love will not allow us to sin against others, for love is the opposite of sin. And when sinned against, we are enabled to forgive others because our Lord Jesus has atoned for that sin. We can reveal God’s forgiveness and love to the offender through our forgiveness.