Chapter 14

1 John 5:4–13

Literary Context

This passage advances and concludes the argument begun in 4:1 concerning the need to discern the origin of spiritual truth, for not every teaching about God has its origin with him (4:1–3). That argument progressed from the need for discernment of the truth to the challenge of overcoming wrong teaching (4:4–6) by listening to the Spirit of truth. Those born of God, who have been given the Spirit of truth, must love one another, for love for God is expressed through love for others (4:7–16). When God’s love reaches its goal, fear of judgment will be gone (4:17–18), because God’s own testimony confirms a “water and blood” gospel as the truth through which eternal life is given.

- XIII. God’s Love Perfected in the Believer (4:17–5:3)

- XIV. The Blood, Eternal Life, and Assurance (5:4–13)

- A. Faith in the Son of God Overcomes the World (5:4–5)

- B. The Testimony (5:6–13)

- XV. Knowing God (5:14–21)

Main Idea

John argues that a “water only” gospel rejects God’s own witness about his Son, Jesus Christ, whose atoning death is necessary for any true spiritual knowledge and assurance of eternal life.

Translation

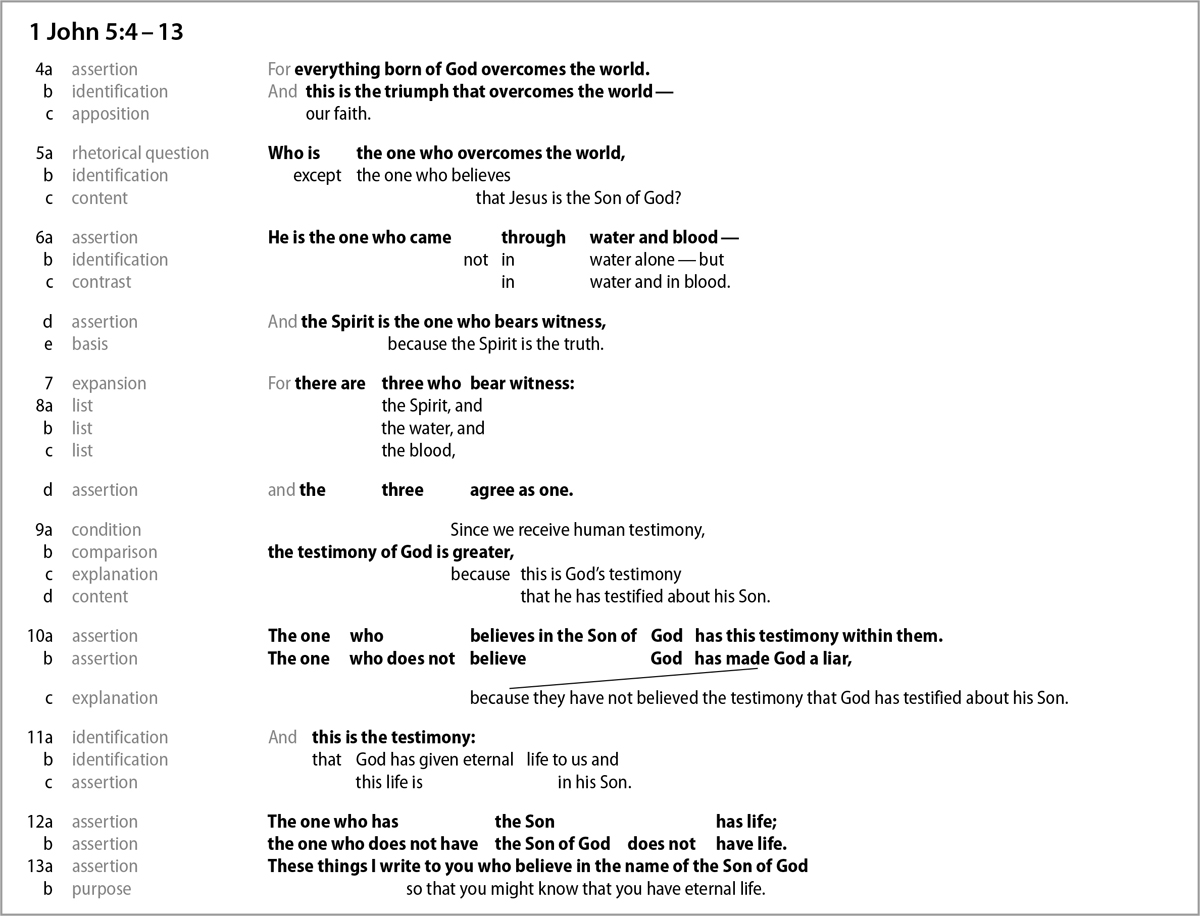

Structure

John’s circular, or braided, thought patterns, in which he returns to topics again and again, has allowed interpreters to see a number of apparently overlapping chiasms.1 Smalley sees in 5:1–4 “a nearly chiastic” structure:2

- A faith and love (v. 1)

- B love and obedience (v. 2)

- B´ love and obedience (v. 3)

- A´ victory and faith (v. 4)

But because 5:3 mentions love for the last time in the letter, this commentary has grouped it with the substantial discussion of that topic in the previous section (4:7–5:3).

Exegetical Outline

- XIV. The Blood, Eternal Life, and Assurance (5:4–13)

- A. Faith in the Son of God overcomes the world (5:4–5)

- B. The testimony (5:6–13)

- 1. Jesus Christ has come through water and blood (5:6a-c)

- 2. The Spirit is the witness to the truth (5:6d-e)

- 3. Three witnesses (5:7–8)

- 4. Receiving God’s testimony (5:9–13)

- a. God’s testimony is greater than human testimony (5:9)

- b. Faith is the necessary response (5:10)

- c. God promises eternal life (5:11–13)

- i. The Son is essential to life (5:11–12)

- ii. Confidence for life is possible (5:13)

Explanation of the Text

5:4 For everything born of God overcomes the world. And this is the triumph that overcomes the world—our faith (ὅτι πᾶν τὸ γεγεννημένον ἐκ τοῦ θεοῦ νικᾷ τὸν κόσμον, καὶ αὕτη ἐστὶν ἡ νίκη ἡ νικήσασα τὸν κόσμον, ἡ πίστις ἡμῶν). Because Jesus destroyed the works of the devil (3:8) and has overcome the world, those who have been born of God (note the perfect tense) also overcome the world by their faith in Christ.

The extensive discussion in 4:7–5:3 has already argued that love for God is inseparably joined to love for others, and the love of both God and others is closely connected to faith in Christ and obedience to God’s commands. The present verse parallels the thought of 5:1 (see the chiastic structure in Structure, above). Verse 1 states that everyone who believes that Jesus is the Christ has been born of God; v. 4a, that everything born of God overcomes the world. Therefore, everyone who believes that Jesus is the Christ overcomes the world.

The use of the neuter (πᾶν) where one would expect the personal generic masculine (πᾶς) occurs elsewhere in John’s writings (John 6:37, 39; 17:2, 24; 1 John 1:1, 3). Translating it as “everyone,” Marshall wonders if the use of the neuter shows the influence of the neuter gender of the Greek words for “child” (τέκνον or παιδίον).3 Or perhaps the elided neuter noun is “spirit” (πνεῦμα). Smalley suggests that its deliberate use here generalizes the reference to “the power of the new birth … not only its possession by each individual.”4 Here it seems to suggest that everything that has its origin in God—the one born of God, perhaps God’s providential working in history, and even faith itself—has happened in order to resist and ultimately triumph over the fallen, sinful, and rebellious tendencies of the world’s order. At the time John wrote, that world included those who had gone out (2:19), and therefore right belief in Christ would overcome even the antichrists’ false teaching.

John does not teach here some enthusiastic triumphalism, but points to faith in the true gospel of Jesus Christ that is “ours,” that is, that held by the author and those who share like faith. In John 16:33 Jesus said that he has “overcome” the world (Gk. perfect, νενίκηκα). Therefore, those who have faith in Christ have faith that this is so, and likewise that faith overcomes all that is of the world (cf. 2:13–14; 4:4; 5:5). The statement here that everything/everyone born of God overcomes the world informs the interpretation of 2:14–15, where the “young men” (νεανίσκοι) are said to be overcomers.

5:5 Who is the one who overcomes the world, except the one who believes that Jesus is the Son of God? (τίς δέ ἐστιν ὁ νικῶν τὸν κόσμον εἰ μὴ ὁ πιστεύων ὅτι Ἰησοῦς ἐστιν ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ θεοῦ;) The answer to this rhetorical question is “no one!” No one can overcome the world except those whose trust is in Jesus Christ. The only one who has overcome the world is Jesus (John 16:33), the Son of God, who came into the world, and he shares his triumph with those who put their trust in him.

John presses the identity of Jesus not simply as a great teacher, prophet, or even the Messiah. He consistently identifies Jesus with God the Father, as God’s Son who shares the divine nature (1:3, 7; 2:22–24; 3:8, 23; 4:9–10, 14, 15; 5:5, 9–13, 20). Without faith in Christ, no one is able to face down the evil, the hopelessness, and the self-defeat that this world presses against us day by day. There may be many self-help gurus who write and speak about how to live a better life, and some of what they say may be helpful and worthwhile. But what is of the world cannot give us victory over the world. Without trust in Christ, who came into the world from God, even the most successful life is swallowed up in the defeat of death.

5:6a-c He is the one who came through water and blood—not in water alone—but in water and in blood (οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ ἐλθὼν δι’ ὕδατος καὶ αἵματος, Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, οὐκ ἐν τῷ ὕδατι μόνον ἀλλ’ ἐν τῷ ὕδατι καὶ ἐν τῷ αἵματι). John further elaborates on the true gospel, that Jesus Christ, the Son of God, “came” through water and blood (5:6a).

How should these two elements, water and blood, be understood? Are they to be taken literally or as symbols of spiritual concepts? Are they a hendiadys or two separate elements?5 Is it exegetically significant that in the first instance John uses the preposition “through” (διά), but in the second clauses uses “in” (ἐν, 5:6b, c), though both can indicate manner (BDF §198[4])? And whether or not John is addressing the teaching of the secessionists (cf. 2:19), it sounds as if there was a real danger of the claim that Jesus Christ came by water alone, and John is emphatically correcting thinking that moves in that direction.

In the first occurrence of “water and blood” (ὕδατος καὶ αἵματος in 5:6a), the two words are joined by the single preposition dia (διά), which has led some interpreters, such as John Calvin, to take it as a hendiadys referring to the cleansing and life-giving effects of Jesus’ death, when blood and water are said to have flowed from Jesus’ side (John 19:34–35; cf. Ezek 36:25–27).6 Michaels follows Calvin in this, explaining that the author of 1 John “interprets the blood and water from Jesus’ side at the crucifixion as a kind of ‘testimony’ (μαρτυρία), comparable to the well-known ‘testimony that God testified about his Son’ at Jesus’ baptism.”7

Although Michaels is almost certainly right that 1 John intends to reassert the significance of Jesus’ death against false teaching, against this interpretation is the second reference to water and blood (5:6c), which clearly separates them by repeating the preposition ἐν and, more importantly, distinguishes the coming in water alone (5:6b) from the coming in water and blood. The fact that 1 John refers to “water and blood” where the gospel has “blood and water” suggests that this was not a conventional hendiadys in use to refer to Jesus’ death. But perhaps most decisively, 5:8 counts three witnesses, not just two—as would be expected if water and blood were a hendiadys referring to Jesus’ death—by separating each of the three with the conjunction “and” (καί) and including a definite article with each.

If the two words are taken as two distinct, literal references, interpreters have suggested that the phrase “water and blood” refers to Jesus’ physical birth and death, respectively, since birth involves the water (amniotic fluid) breaking (but also involves blood).8 Or perhaps the water refers to Jesus’ baptism that inaugurated his public ministry.9 Either way, John’s emphasis on not in water alone might then suggest that the significance of Jesus Christ is not in just his earthly life as a teacher and religious leader, but that his death is also significant and relevant.

In the tradition of Tertullian, Augustine, and Ambrose, some have suggested that “water and blood” might refer to the two sacraments of water baptism and the Eucharist as modes in which Christ comes into a believer’s life, but some modern interpreters, such as Schnackenburg, see sacraments in v. 7 but a historical reference to Jesus’ life in v. 6.10 This reading is similar to that of the debate in studies of John’s gospel whether the bread-from-heaven discourse in John 6, written some decades after Jesus’ lifetime, was intended to refer to the Eucharist, especially John 6:54, “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life.” But rather than a direct reference to the Eucharist, eating and drinking in John 6 is a metaphor for believing in the atoning value of Jesus’ death, the event to which the Eucharist also points.

A eucharistic reading of 1 John 5:6 would mean taking “water” literally as the element of the sacrament of baptism, but the blood comes into a believer’s life figuratively through the wine or juice drunk at Holy Communion. Moreover, “blood” would be an unprecedented way of referring to the Eucharist. Furthermore, there is no other reference to the Eucharist in John’s letters that would suggest this was part of the controversy. Also against this reading is the aspect of the substantival aorist participle “the one who came” (ὁ ἐλθών), which Witherington argues is decisively against a sacramental reading, since the verb is not “in the present tense indicating an ongoing coming,” presumably into the life of the believer through the sacraments.11

Tom Thatcher proposes that “water” is a symbol of the Holy Spirit and “blood” a symbol of the physical nature of Jesus culminating in the atonement on the cross.12 He argues that the secessionists were pushing Jesus’ paraclete statements in John 13–17 beyond the limits of orthodoxy. Misunderstanding might arise from Jesus’ statements that he would come to his disciples by the Spirit of truth whom he would send (John 14:16–18), that the Spirit would be the disciples’ guide into all truth (16:13–15), and that the Spirit would teach them “all things” (14:26). Some may have used such statements to argue against the return of Christ after the Spirit came at Pentecost. Or perhaps some rejected the teaching of the apostles on the mistaken belief that the Spirit was the only teacher they needed. Perhaps the secessionists claimed that the Spirit had given them the teaching that John found heretical.

Thatcher’s interpretation recognizes the frequent use of water in John’s gospel to symbolize the Holy Spirit—for example in John 4, where Jesus promises “living water” for those who would believe in him. John 7:37–39 explicitly identifies “living water” as the Spirit who would be given to believers after Jesus was glorified. This symbolic use of water is a metaphor for the Spirit and also the constellation of associations that John makes with the Spirit, such as the impartation of truth and eternal life (see The Theology of John’s Letters). Thatcher suggests that when the antichrists argued that Jesus came through water only, they meant that “everything significant about Jesus has been revealed to the Church through the Spirit,” which led to diminishing the significance of Jesus’ life and death, perhaps leading to claims of new revelations that were not consistent with apostolic teaching.13

This view coheres with John’s emphasis on apostolic authority that opens the letter (1:1–4) and the fact that something had happened that led people to leave the Christian community where John’s apostolic authority was present (2:19). Thatcher’s theory also provides a context to understand John’s statement in 2 John 9, “Everyone who goes beyond and does not remain in the teaching of Christ does not have God.” The biggest argument against Thatcher’s interpretation is 5:8, where both the Spirit and the water are listed separately as two of the three witnesses.

If the use of the verb “come” (ἔρχομαι) here carries the connotation of Christ’s salvific mission, as argued in our comments on 4:2, then the prepositional phrases “in the water” and “in the blood” in 5:6c (ἐν τῷ ὕδατι and ἐν τῷ αἵματι) are instrumental datives adverbially modifying the elided verb “come” (ἐλθών), which suggests that the salvific mission of Jesus was achieved both by water and by blood, not by water alone. The discussion of 4:2, where the similar phrase “Jesus Christ has come in flesh” was first mentioned, does occur in the context of discerning spiritual truth and recognition that not every teaching is from the Holy Spirit.

The reason 1 John 5:6 is such a conundrum for us no doubt has to do with the fact that “1 John is written to people who know what the secessionist crisis is about firsthand. These readers of 1 John thus frequently need only a brief, allusive phrase to know what the author is referring to.”14 For those in the Johannine church(es) the phrases “Jesus Christ has come in flesh” (4:2) and “came through water and blood” (5:6) probably called to mind teaching and context that subsequent readers lack. That historical factor is further complicated for subsequent readers by the multiple connotations of the “water” symbol we observe in John’s gospel. So how is water to be understood here in 5:6?

Thatcher is likely right that John’s correction of false teaching is needed because of a misconstrual of the water symbol in the gospel. As Thatcher explains:

John and the “AntiChrists” appealed to the same Jesus tradition, but interpreted that tradition in radically different ways. While the AntiChrists emphasized the believer’s continuing revelatory experience via the Spirit, John insisted that new revelations must be “consistent with” the apostolic teaching about the historical Jesus.15

Close attention to the syntax suggests that John refers to “water alone” to allude to the false teaching he is about to correct, but then uses it as part of a reference to Jesus’ earthly life (“water and blood”). The first mention of “water and blood” in 5:6a (ὁ ἐλθὼν δι’ ὕδατος καὶ αἵματος) probably is a hendiadys referring to the atoning humanity of Jesus, with water likely a reference to his baptism, in which the Spirit’s testimony plays a central role (John 3:32–34). “Water and blood” refers to the earthly life of Jesus in its efficacy for atonement.

The separation of the terms “water” and “blood” in their second occurrence in 5:6c by the repetition of the preposition and article (ἐν τῷ ὕδατι καὶ ἐν τῷ αἵματι) is the clue that John is breaking up the hendiadys because he needs to correct a misconstrual of the “water” symbol. John mentions water first because he does want to affirm the salvific connotation represented by “water” as a metaphor for the Spirit, but he also wants to add to it the essential element of “blood.” The Spirit is essential because he applies atonement to the believer’s life. But the blood is essential as the objective basis of that atonement. John does need to affirm the role of the Spirit in salvation, so he cannot say simply “not by water” and leave it at that. As a corrective statement it makes sense that John uses “water” in a double sense—first in reference to the way the false teaching about the Spirit is employing it, and then in a correction that refers to the water and the blood as symbols of the atoning life of Jesus.

If so, the thought needing correction probably is that some were identifying “water” with the Spirit (as per Thatcher).16 But he then offers the correction that salvation is achieved not by the water (Spirit) alone (5:6b) but by the water and by the blood (5:6c), that is, by Jesus’ atoning humanity. So understood, John is tying the presence of the Spirit, who is the witness to the truth in the church after the resurrection, to the Spirit’s witness of both the baptism of Jesus and his death. It was the Spirit who descended on Jesus at his baptism, providing a witness of Jesus’ true identity (John 1:32–34). And when Jesus “gives up” his spirit on the cross, his death releases the Spirit to come (19:30; 20:22; cf. his teaching in 16:7 about the necessity of his going away for the Spirit to come). In other words, John argues that there is no testimony from the Spirit that ignores or contradicts the atoning death of Jesus, which was likely involved in what the false teachers were suggesting.

While we may never know the exact problem with the thinking of the secessionists, the correction presented in 5:6, 8 addresses at least two false ideas: (1) that the significance of Jesus was focused only in his teachings and miracles, as opposed to his death and resurrection, which suggests that Jesus was nothing more than a prophet or a religious teacher; (2) that everything significant about Jesus is revealed to the church by the Spirit as an ongoing source of revelation, perhaps with claims to truth not organically related to and consistent with the atonement of Jesus’ death (cf. 2 John 9).

John does not deny the role of the Spirit, but he anchors it in the historical life of Jesus, of whose significance the Spirit reminds the church. Either of these two false directions opposes the redemptive mission of Jesus Christ and is therefore “antichrist” in nature (cf. 2:18–23). By this understanding, John is opposing any teaching that demotes or eliminates the cross, a heresy symbolized by a “water only” gospel; the full significance of the incarnation of Jesus Christ is upheld only by a “water and blood” gospel.

John’s correction would thus speak against a docetic Christology, such as Cerinthianism, but it is not necessary to presume that particular heresy. John must uphold the presence and power of the Holy Spirit in the believer’s life while also holding the historical Jesus to be essential to the Christian faith. The Spirit alone is insufficient because our sin must be atoned for. Jesus’ physical life and death as a human being is at the heart of the atonement, without which no true knowledge of or fellowship with God is possible (cf. 1:7, 9).

5:6d-e And the Spirit is the one who bears witness, because the Spirit is the truth (καὶ τὸ πνεῦμά ἐστιν τὸ μαρτυροῦν, ὅτι τὸ πνεῦμά ἐστιν ἡ ἀλήθεια). John continues to affirm the role of the Spirit in the gospel of Jesus Christ. Here we see the necessity of holding together both the objective, historical event of Jesus’ atoning crucifixion, which is independent of any individual’s opinion about it, and the personal wooing and witness of the Holy Spirit, who applies that atonement to the individual believer. While the Spirit is necessary for salvation, his role is always coupled to and anchored in the earthly life of Jesus Christ, sent by the Father as an atoning sacrifice for sin. Even though the Spirit continues to speak to the church, his witness is in complete harmony with the truth, the orthodox teaching of the atonement of Jesus Christ.

Twice John has stated that God has given “us” the Spirit (3:24; 4:13), and in both occurrences it is the presence of the Spirit that confirms to the believer that God lives in them and they in God. The presence of the Spirit is evidenced when the believer listens to and accepts the apostolic witness as the truth (4:6); any other truth claim not consistent with that witness is deemed not of God and is therefore false. In this way, the genuine presence of God is identified with an objective set of knowledge that originated with Jesus and was codified in the testimony of apostolic witnesses, such as that of the beloved disciple of John’s gospel and the elder of the Johannine letters. In this sense the Spirit is the truth, and any truth claim apart from the apostolic teaching cannot be of the Spirit of God. Therefore, the Spirit is the one who bears witness to an individual that the apostolic teaching of the gospel is true and trustworthy (note the present tense suggesting the ongoing work of the Spirit).

5:7–8 For there are three who bear witness: the Spirit, and the water, and the blood, and the three agree as one (ὅτι τρεῖς εἰσιν οἱ μαρτυροῦντες, τὸ πνεῦμα καὶ τὸ ὕδωρ καὶ τὸ αἷμα, καὶ οἱ τρεῖς εἰς τὸ ἕν εἰσιν). John underscores here the witness of three distinct but inseparable elements of the salvation that expresses the Father’s love through the atoning death of Jesus, the Son of God, which has been recognized as the truth by all genuine believers.

John personifies the water and the blood as witnesses that, while referring to the earthly life of Jesus, continue to witness to God’s love and offer of redemption throughout all time. The “blood” is unambiguously a reference to the death of Jesus that continues to “witness” throughout time. The specific referent of “water” remains obscure and may be intended to connote multiple connotations alluding to John’s gospel (see comments on v. 6). Calvin seems to suggest the Spirit is one witness but mentioned twice.17 Thatcher wonders if it might not be two aspects of the Spirit’s witness: first, his close association with events during Jesus’ earthly life, and then his ongoing work in the church after Jesus’ death and resurrection.18

The witness of the Spirit was prominent in both Jesus’ baptism and his death. Jesus’ public ministry began when the Spirit descended on him at his water baptism (Matt 3:13–17; Mark 1:9–13; Luke 3:21–23; John 1:29–34). Although John’s gospel does not include the story of Jesus’ baptism, it does highlight the testimony of John the Baptist (John 1:19–36), and he was the one who first identified Jesus as Son of God when the Spirit descended as a dove. In John’s gospel the death of Jesus is linked to the giving of the Holy Spirit in a scene that evokes God’s breathing life into his human creation (John 19:30, 34; 20:22; cf. Gen 2:7 LXX). What is clear is the unity of the three that bear witness—literally in the Greek “are into one” (note neuter gender, ἕν). This unity of redemptive purpose refutes whatever ideas concerning the Spirit, the water, and the blood were leading people into falsehood, probably distortions of these three elements as they occur in John’s gospel.

The mention of three witnesses was apparently a convention of that culture (cf. Deut 17:6; 19:15; Matt 18:16; 2 Cor 13:1). The recognition of the involvement of the three persons of Father, Son, and Spirit as trinitarian doctrine developed probably led to the insertion of what is now known as the Johannine comma, which appears in Latin manuscripts but not in any Greek earlier than the fourteenth century. While modern English uses the word “comma” to refer to a punctuation mark, in earlier English usage it referred to a phrase. The Johannine comma is an additional phrase inserted between 5:7 and 5:8 that still appears in Bibles that use the same Greek text from which the King James Version was translated in 1611. It reads (additional phrase in italics):

For there are three who testify in heaven:

Father, Word, and Holy Spirit;

and these three are one;

and there are three who testify on earth:

the Spirit and the water and the blood;

and these three agree as one.

While it is virtually certain that John did not write this additional phrase, it represents an interpretation that captures the unity of the Godhead with respect to salvation that is reflected in the earthly life of the incarnate Son and the ongoing work of the Holy Spirit in human lives.

5:9 Since we receive human testimony, the testimony of God is greater, because this is God’s testimony that he has testified about his Son (εἰ τὴν μαρτυρίαν τῶν ἀνθρώπων λαμβάνομεν, ἡ μαρτυρία τοῦ θεοῦ μείζων ἐστίν, ὅτι αὕτη ἐστὶν ἡ μαρτυρία τοῦ θεοῦ ὅτι μεμαρτύρηκεν περὶ τοῦ υἱοῦ αὐτοῦ). John first establishes that what he is saying is not just of human origin, but has its ultimate origin in God. The first class condition, or condition of fact, states the assumption that human testimony is accepted routinely as one of our epistemological sources. We can know something by direct experience, by logical inference, or by believing what someone else tells us. If one is willing to receive human testimony, how much more should one be willing in principle to accept the testimony of the all-knowing God.

But that is not quite the reason John gives for the superiority of God’s testimony. The first hoti clause is a causal clause (“because”), and it introduces a christological reason; the second is epexegetical: “this is God’s testimony” = what “he has testified about his Son.” God’s testimony about the Son trumps any merely human ideas such as those John was attempting to correct.

The referent of the demonstrative pronoun “this” (αὕτη) points forward to the hoti clause. What is God’s testimony? It is the testimony he has given (note perfect tense), and that testimony already given is not about generic spiritual principles but is about his Son, Jesus Christ. God first gave his testimony at the baptism of Jesus when he identified Jesus as his Son (Matt 3:17; Mark 1:11; Luke 3:22; John 1:33). In John’s gospel, John the Baptist hears and preaches God’s testimony about his Son, accrediting Jesus’ words. The Baptist explains, “The one who comes from heaven is above all…. He testifies to what he has seen and heard…. Whoever has accepted it [his testimony] has certified that God is truthful” (John 3:31–33).

The beloved disciple of John’s gospel is the one “who testifies to these things and who wrote them down. We know that his testimony is true” (John 21:24). Testimony is a central theme of John’s gospel, which is itself God’s testimony about Jesus. In 1 John, that testimony is “what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have perceived, and our hands have touched” (1 John 1:1). Perhaps 1 John 5:9 is an invitation to read John’s gospel as a speech act of God’s deposition concerning the identity of Jesus.

The author of 1 John assumes that his testimony about the truth stands in unbroken lineage back to God’s testimony about Jesus, and he is zealous to protect it from all other, errant claims to truth, such as those apparently offered by the antichrists. The witness of the Spirit, the water, and the blood are all integrally a part of God’s testimony. Therefore, 5:9 is making not just a general claim that God’s testimony is greater than human testimony, but the specific claim that the nature of God’s testimony is about Jesus, not anything or anyone else.

5:10 The one who believes in the Son of God has this testimony within them. The one who does not believe God has made God a liar, because they have not believed the testimony that God has testified about his Son (ὁ πιστεύων εἰς τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ θεοῦ ἔχει τὴν μαρτυρίαν ἐν αὑτῷ·20 ὁ μὴ πιστεύων τῷ θεῷ ψεύστην πεποίηκεν αὐτόν, ὅτι οὐ πεπίστευκεν εἰς τὴν μαρτυρίαν ἣν μεμαρτύρηκεν ὁ θεὸς περὶ τοῦ υἱοῦ αὐτοῦ).

The Christian is, by John’s definition, one who has heard the NT witness, has recognized it as God’s interpretation of the significance of the life and death of Jesus his Son, and has internalized it as their own belief. But the rejection of the gospel of Jesus Christ is not a morally neutral act. John would not look favorably on the pluralistic, culturally centered view of religious belief that is so popular today, that one’s belief is what is true for you but has no claim on me. Precisely because the apostolic testimony about Jesus is God’s testimony, to hear it and not believe it entails making God a liar.

This is the second time John mentions making God a liar. The first time (in 1:10) involves the denial of personal sin. God says that human beings are sinners who are alienated from him, living in darkness with death their only future. But in his love he sent his Son to atone for that sin, to reconcile people to himself. Note the repetition of the phrase from 5:9, “God has testified about his Son” (μεμαρτύρηκεν ὁ θεὸς περὶ τοῦ υἱοῦ αὐτοῦ). God has given his testimony, and it stands for all time. When someone rejects God’s love offered in Christ in favor of some other system of belief (or nonbelief), they implicitly declare that they know better than God, thus “making” him a liar.

5:11 And this is the testimony: that God has given eternal life to us and this life is in his Son (καὶ αὕτη ἐστὶν ἡ μαρτυρία, ὅτι ζωὴν αἰώνιον ἔδωκεν ἡμῖν ὁ θεός, καὶ αὕτη ἡ ζωὴ ἐν τῷ υἱῷ αὐτοῦ ἐστιν). The testimony of God is firm, rooted in his character, revealed in his Son, and witnessed by the Spirit, the water, and the blood. John now brings his argument back to address the assurance he wishes his readers to have. God testifies, and he cannot lie, that he offers to all (2:2) what he gave to “us” who have believed his testimony about his Son, namely, the gift of eternal life that is found in no one other than God’s Son, Jesus Christ. So closely does John’s argument link God’s testimony about Jesus to the witness of the Spirit, the water, and the blood that any claim that excludes the Spirit, the water, or the blood is not God’s testimony, but merely human ideas devoid of the power to save and assure.

5:12 The one who has the Son has life; the one who does not have the Son of God does not have life (ὁ ἔχων τὸν υἱὸν ἔχει τὴν ζωήν· ὁ μὴ ἔχων τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ θεοῦ τὴν ζωὴν οὐκ ἔχει). This statement summarizes what John has been discussing since 4:1, where he points out that not all “truth” is God’s truth, but only that which is of the Spirit in accord with the significance of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection.

The expression “the one who has the Son” is similar to 2:23, where John states that the one who “has” (ἔχει) the Father is “the one who acknowledges the Son,” and the one who denies the Son does not have the Father either. This is another way of saying that Jesus Christ is the only way to God (cf. John 14:6), a thought that was just as off-putting to ancient society as it is to many people today.

5:13 These things I write to you who believe in the name of the Son of God so that you might know that you have eternal life (Ταῦτα ἔγραψα ὑμῖν ἵνα εἰδῆτε ὅτι ζωὴν ἔχετε αἰώνιον, τοῖς πιστεύουσιν εἰς τὸ ὄνομα τοῦ υἱοῦ τοῦ θεοῦ). John now begins to bring his letter to a close, forming an inclusio with 1:4. As 1:4 marks a transition between the opening and body of the letter, 5:13 marks a transition between the body and the closing, and it could be grouped either with what precedes or with what follows. It is considered here because it continues the same topic of eternal life mentioned in 5:11–12.

John begins to draw his letter to a close by reminding his readers that his purpose is to reassure them that they were right to believe in Christ, and exhorting them to continue to do so even in the wake of whatever disturbance has recently troubled the church (cf. 2:19; 4:1). This is the third assurance John gives his readers after addressing the false ideas about Christ and Christian living to which they were likely exposed (cf. 2:12–14, 20–21).

The aorist tense of the verb (ἔγραψα) is epistolary and refers not to a previous letter (“I wrote”) but to the present letter (“I write”). After opening the letter with the first person plural “we write” (γράφομεν), the author switches to the singular “I write” throughout the rest of the letter, consistently using the present tense in 2:1, 7, 8, 12, 13 and then switching to the aorist in 2:14, 21, 26; 5:13. The demonstrative pronoun (ταῦτα) most likely refers to all that has been previously written, because the theme of eternal life was introduced in the opening of the letter (1:2), and the topics of sin, love, and right thinking about who Christ is have all been linked to it (e.g., 1:7; 2:9; 5:6).

This verse is strikingly similar to the purpose statement of the Fourth Gospel in John 20:31: “These are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name.” The gospel is logically prior in its relevance to believers, since it presents reasons to believe; 1 John exhorts those who have believed to continue in that faith, even in the face of confusing circumstances.

Theology in Application

What We Believe about the Future Determines How We’ll Live Today

In the busyness of daily life, it is easy to lose sight of one’s eternal future and not even give it a thought until one is confronted with mortality at the grave of a friend or loved one. The priorities of our modern lives probably include working, meals, worship, exercise, shopping, mowing the grass, maintaining our homes and cars, spending time with family and friends, and so on. The importance of life after death seldom comes to mind, even for Christian believers.

Yet nothing seems to have been a greater concern to the author of John’s gospel and letters than securing people in the only source of eternal life, Jesus Christ, the Eternal Life sent to earth to die and to open the way through death to life for all who would believe and follow. Jesus’ atoning death—the “water and blood” gospel—is the heart of Christian theology. No theology that claims otherwise can be true, for God’s testimony confirms only a “water and blood” gospel, not a “water only” gospel. Today’s theological trend toward a “nonviolent” atonement, while perhaps well intentioned, is a modern expression of the kind of thinking the apostle corrects by reminding his readers that Jesus Christ did not come by water only, but that his blood is essential for the atonement that secures our eternal life after death.

Is What We Believe That Important?

Many in modern society don’t seem to think that one’s choice of a particular religious belief, or no religious belief, is an important decision. It certainly isn’t viewed as a life-or-death matter. But rejecting the offer of eternal life in Jesus Christ is not a morally neutral decision (see The Theology of John’s Letters). John says that whoever hears the gospel and refuses to believe it implicitly calls God a liar, for the Christian witness to the gospel has its ultimate origin in God’s witnessing revelation that Jesus is his Son who was sent to atone for our sins (5:10).

John’s teaching corrects a smorgasbord approach to belief in God that is just as popular today as it was in the first century. We live in a world with many religions, and we increasingly rub elbows in our workplaces and neighborhoods with the people who practice them. Many of these religions teach and practice good moral principles, and our colleagues and neighbors may be very fine, upstanding people. In fact, they may be nicer and better people than some of the Christians we know! It may be tempting in today’s social climate to “water down” the gospel of Jesus Christ, denying the need for atonement for sin or emphasizing the common moral principles that Christianity shares with other religions. Against the polite, but erroneous, belief that all religions lead to God, Jesus states, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6).

It is no accident that these three terms, “way,” “truth,” and “life,” are coupled in this statement. As a religious belief, only Jesus is the way to God because only Jesus atoned for sin and then rose victorious from his grave. Only Jesus came from God, as God enfleshed in a human body like ours, and he came to reveal the otherwise unseen and invisible God. Therefore, any spiritual truth claims not based on this revelation of God in Christ are just whistling in the dark. Finally, Jesus is the life, first because his own eternal life as a member of the Godhead was enfleshed in his human body (1 John 1:2), and second because his human body arose from the grave. It is through his eternal life that we live (cf. John 14:19).

John’s purpose in writing the letter we know as 1 John was to bring assurance of eternal life to his readers, who were apparently being exposed to a “water only” gospel. He points out the necessity of a “water and blood” gospel that embraces the cross of Jesus and doesn’t preach just the teachings of Jesus, or the blessings of Jesus, or the spirit of Jesus, as many seem inclined to do today. A “water only” gospel might satisfy some for this life, but its value stops at the grave. For it provides no assurance of reconciliation with God, no atonement for our sin, and no promise of life after death.