Chapter 18

2 John 9–11

Literary Context

These verses form the climax of the letter by presenting the most pressing issue on the elder’s mind: keeping false teachers from influencing other churches. Using strong language, the elder draws a sharp line dividing those who walk in the truth from those who have gone beyond the bounds of orthodoxy. He delivers a clear prohibition against giving any standing in the community to those who bring a message about God and Christ other than what the apostles have proclaimed.

- I. Salutation and Greeting (vv. 1–3)

- II. An Exhortation (vv. 4–8)

- III. A Prohibition (vv. 9–11)

- A. Anyone Who Does Not Hold to the Teachings of Christ Does Not Have God (v. 9)

- B. A Prohibition against Receiving False Teachers (v. 10)

- C. To Welcome a False Teacher Is to Share in Their Evil Work (v. 11)

- IV. Closing (vv. 12–13)

Main Idea

Verses 9–11 form the center of the letter and the major point the elder wishes to communicate. His main concern is to prevent his original readers from welcoming false teachers into their community. To be a disciple of Jesus Christ, to have assurance of eternal life, to know God truly, one must continue to hold to the apostolic teaching about Jesus Christ. Furthermore, to aid and abet teaching outside the bounds of orthodoxy is to share in an evil work.

Translation

Structure

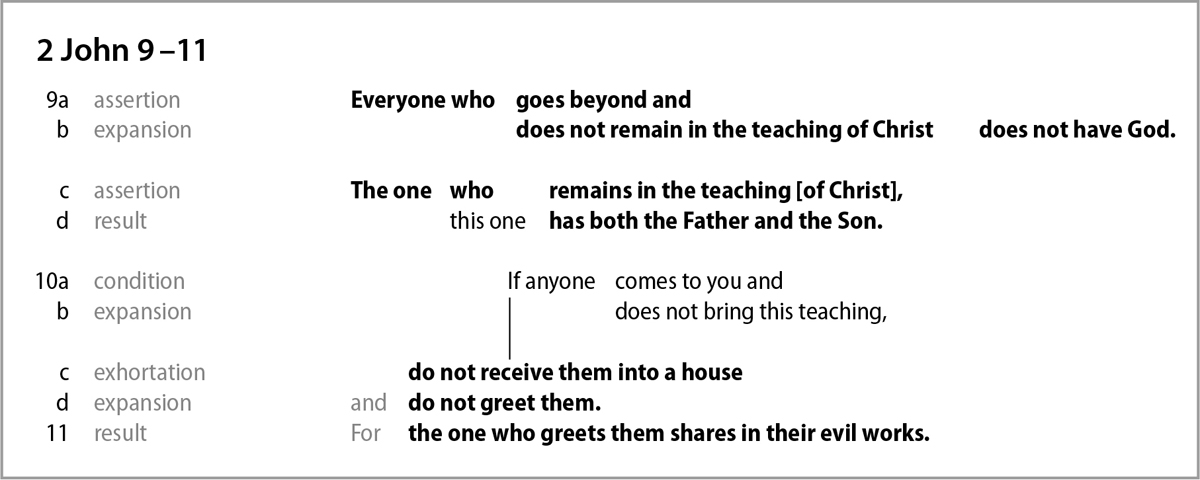

Verses 9–11 expound on the statement of v. 8, explaining how listening to the deceivers who have gone out destroys the apostolic work. They consist of two assertions surrounding a conditional statement, which forms the major point of the letter.

Exegetical Outline

- III. A Prohibition (vv. 9–11)

- A. Anyone who does not hold to the teachings of Christ does not have God (v. 9)

- B. A prohibition against receiving false teachers (v. 10)

- C. To welcome a false teacher is to share in their evil work (v. 11)

Explanation of the Text

9 Everyone who goes beyond and does not remain in the teaching of Christ does not have God. The one who remains in the teaching [of Christ], this one has both the Father and the Son (Πᾶς ὁ προάγων καὶ μὴ μένων ἐν τῇ διδαχῇ τοῦ Χριστοῦ θεὸν οὐκ ἔχει· ὁ μένων ἐν τῇ διδαχῇ, οὗτος καὶ τὸν πατέρα καὶ τὸν υἱὸν ἔχει). The serious possibility of destroying one’s spiritual foundation in Christ is further explained in vv. 9–11. Here the elder points out that those who go beyond the teaching of Christ go outside of it and do not have God.

The word rendered here as “goes beyond” (προάγων) is translated variously as “runs ahead” (NIV), “wander away from” (NLT), “goes too far” (NASB), “goes on ahead” (ESV), “goes beyond” (NJB)—all capturing the sense here in contrast to remaining in the teaching of Christ, a major theme in John’s writings. Yarbrough abandons the metaphor of movement and translates the sense “everyone who innovates” in their beliefs.1 In Johannine thought, remaining in the teaching of Christ is synonymous with walking in the truth, which funds the metaphor of movement beyond the bounds in the use of the verb “go beyond” (προάγων).

The genitive in “in the teaching of Christ” (ἐν τῇ διδαχῇ τοῦ Χριστοῦ) may be either objective (the teaching about Christ) or subjective (Christ’s teaching). If subjective, it cannot be strictly limited to the teaching of Jesus during his earthly life, for Jesus himself promised that his apostles would receive further understanding from the Spirit after his death and the arrival of the paraclete (John 14:26; 16:14, 15). Teaching given by Jesus becomes teaching about Christ after he is no longer on earth. For that reason (and note further that the elder specifies the teaching of Christ, not of Jesus, or even of Jesus Christ), it may be best to view the genitive as objective, the teaching about Christ, which of courses include Jesus’ teaching as preserved and proclaimed by those who saw him, heard him, and touched him (1 John 1:1–4).

While there may be room to gain new insights throughout church history—we do need biblical scholars and theologians—not any and every teaching about God or Christ is within the bounds of apostolic orthodoxy. And as Jesus himself pointed out, “If you hold to my teaching [ἐὰν ὑμεῖς μείνητε ἐν τῷ λόγῳ τῷ ἐμῷ], you are really my disciples” (John 8:31). Only by holding to the teaching of Christ can one claim to be a follower of Jesus. Some ideas being held and taught by some segment in the Johannine church(es) at the time this letter was written were outside of the bounds of orthodoxy.

To move in one’s thinking beyond the teaching of Christ is to remove oneself from relationship with God (to not have God), for the teaching that originated with Jesus, that which was illuminated by the Holy Spirit and preserved by the apostles, came from God himself (John 7:16, 17). The one who has both the Father and the Son is specified by the demonstrative pronoun “this one” (οὗτος), which refers to “the one who remains in the teaching” (ὁ μένων ἐν τῇ διδαχῇ); that is, the definite article “the” (τῇ) is anaphoric, referring back to the previously mentioned teaching, i.e., the teaching of Christ.

Here again, the elder points out the seriousness of the situation facing the people in the Johannine congregation(s). In v. 8 he warned against following the deceivers’ teaching and losing one’s “full reward,” eschatological language for eternal life after death. Here he warns that such beliefs lie outside the bounds of a relationship with God (cf. 1 John 1:3).

10 If anyone comes to you and does not bring this teaching, do not receive them into a house and do not greet them (εἴ τις ἔρχεται πρὸς ὑμᾶς καὶ ταύτην τὴν διδαχὴν οὐ φέρει, μὴ λαμβάνετε αὐτὸν εἰς οἰκίαν καὶ χαίρειν αὐτῷ μὴ λέγετε). This is the second instance of a command expressed in the imperative in the letter, in this case a double prohibition, and it is probably the reason the elder wrote this letter.

The readers must not welcome those who have gone out from the elder’s church, or anyone else, who does not bring “this teaching,” that is, the teaching of Christ as proclaimed by the apostles. If 2 John was a cover letter for 1 John, then “this teaching” may have the broader reference to the content of that book (see discussion in Introduction to 2 and 3 John). The indefinite pronoun “anyone” (τις) suggests that the elder is aware of the potential for false teachers to infiltrate churches. Those who went out from his church (1 John 2:19) are perhaps only one urgently pressing instance.

Hospitality for travelers was an important aspect of ancient culture; it was an essential part of Jesus’ ministry when he sent out the Twelve (Matt 10:11–14). The gospel spread through early groups of believers who had contact with an apostle and then went on to other locations, taking the gospel with them, but likely not having adequate training to teach soundly. This spontaneous expansion of the church inevitably resulted in problems of conflicting teaching and of heresy.

Early Christianity was not monolithic; Paul’s letters, John’s gospel and letters, and the book of Revelation testify to the diverse nature, questions, and issues of Christianity in Asia Minor. Other forms of Christianity developed in Asia Minor as well, such as the Montanists in the province of Phrygia, who were eventually condemned in AD 177 by Apollinaris, bishop of Hieropolis. The geographical proximity of this group to the Johannine churches raises the question if their errant theology developed from false teaching similar to that of those who had gone out of the elder’s church(es). The letters of Ignatius to churches in the same area (Ephesus, Magnesia on the Maeander, Tralles, Philadelphia, and Smyrna) indicate that there were many such Christian groups on the fringes of apostolic orthodoxy.

Extending hospitality in Greco-Roman culture gave one’s guests a standing in the community equal to one’s own standing. Therefore, to provide shelter and food for travelers was not simply a hospitable act; it had social ramifications beyond the immediate household involved. As Lieu observes, hospitality “was not only a social necessity but also established or reinforced bonds between different communities, building up the networking that was such an important feature of the growth of the early church.”2 Although the church councils were eventually necessary to reach consensus on orthodoxy, the nature of how the early church spread and developed fostered tension between individual groups of believers in one location and centers of orthodoxy where the apostles had resided.3

The elder’s prohibition is not speaking about pagan friends or unbelieving relatives, but of those travelers who professed to be Christian in a teaching role, who may have had some standing in the church at large, but who were undermining apostolic authority and teaching. The point of the elder’s strong exhortation was to deny even the slightest opportunity for false teachers to influence or infiltrate the church, especially when the church of that time was meeting not in church buildings but in private homes.

There is some debate whether the prohibition against greeting such a person (χαίρειν αὐτῷ μὴ λέγετε) meant even a simple “hello”4 or a greeting that would acknowledge the person as a fellow Christian.5 The infinitive “to greet” (χαίρειν) was the conventional greeting in personal correspondence (cf. Acts 15:23; 23:26; Jas 1:1)6 and perhaps was intended to prevent any opportunity for private conversation that could infect the church. Ignatius, writing to the church at Smyrna, expresses the thought that it is better to not even meet such people:

But I am guarding you in advance against wild beasts in human form—people whom you must not only not welcome but, if possible, not even meet. Nevertheless, do pray for them, that somehow they might repent, difficult though it may be. But Jesus Christ, our true life, has power over this.7

However, it is difficult to know how someone would be aware of what kind of teaching a traveler was bringing if there was no communication whatsoever. In either case, it would be clear to others that the false teacher was not to be given any standing in the community, making it hard for them to gain a hearing before the church (cf. Jude 3–4, 12, 19).

There are many extant letters of introduction requesting a friend or relative who lived in a distant place to extend hospitality to a traveler passing through who was otherwise a stranger, and 3 John is an example of such a letter (see Introduction to 3 John).8 The elder’s teaching here concerning hospitality creates an ironic contrast with the situation presented in 3 John, where it is the elder’s own people who are being refused hospitality by Diotrephes and his church (see commentary on 3 John 9–10).

11 For the one who greets them shares in their evil works (ὁ λέγων γὰρ αὐτῷ χαίρειν κοινωνεῖ τοῖς ἔργοις αὐτοῦ τοῖς πονηροῖς). Social gestures are not always spiritually neutral acts. The elder ups the ante here with this final comment that indicts anyone who greets a false teacher as sharing in the evil works of the false teachers. Lieu comments, “The elder’s injunction remains disturbingly rigorous,”9 especially given that hospitality was considered a Christian virtue (cf. Acts 16:15; Rom 12:13; 1 Tim 3:2; 5:10; Titus 1:8; Heb 13:2; 1 Pet 4:9). Indeed, it may seem over the top when viewed from our modern social context of pluralism and ecumenical gestures.

But that was then and this is now. The Christian church with its orthodox creeds and practices has been long established, but when the elder wrote, the infant church was most vulnerable. The decentralized, scattered groups of Christians in the first century, before the NT existed, relied on itinerant teachers and preachers. Those who had “gone out” with a false message (1 John 2:19) had departed from the elder’s church; that perhaps made them all the more dangerous. Their former association with the elder’s church may have created a perception of good standing that could deceive the outlying churches in the region; that may account for the harshness with which the elder expresses his warnings. To protect the integrity of the infant church, the issues had to be drawn in black and white, or light and darkness, to use the Johannine duality.

“Evil works” (τοῖς ἔργοις … τοῖς πονηροῖς) are mentioned elsewhere in John’s writings. In the gospel, it is their “evil” works that made people reject Jesus (John 7:7) and love the darkness more than the light (John 3:19). In 1 John, Cain is held up as the paradigmatic sinner, whose works were evil and who was “of the evil one” (1 John 3:12). The elder says here that to aid and abet false teaching that is not “of Christ,” even if the false teachers themselves claim to be Christian and may have all good intentions, is to “share in” (κοινωνεῖ) the works of darkness.

Not any and all spiritual teaching about God and Christ is of the truth, and what is not of the truth is of the darkness. To give credence and aid to false teaching is to keep people in darkness and, to that extent, to forfeit fellowship in the light. For genuine Christian fellowship with the elder, the Father, and Jesus Christ is based on embracing the proclamation of those who have seen, heard, touched, and perceived the true significance of Jesus’ earthly life (1 John 1:1–3). True fellowship with God and with one another is based not on shared personal opinion or common social factors, but on walking in the truth, on remaining in the teaching of Christ.

Theology in Application

Ecumenical or Not?

We live in a pluralistic age animated by an ecumenical spirit. We also live at a time when we possess the complete NT and long after Christian orthodoxy has been established by the historic church councils. But the church today needs discernment no less than it did when the elder wrote. While the church at large is probably not in danger of being destroyed, individual lives and congregations are still at great spiritual risk.

It is interesting that of all the NT writers, the Johannine author repeatedly stresses the need for Christians to love one another as an expression of their love for God. But it is the same author who so boldly prohibits social interaction with professing Christians who do not embrace the orthodox, apostolic message. Is it not unloving to shun another professing Christian? Apparently the elder does not think that love, as paramount as it is to the Christian life, trumps truth—and that is perhaps the great sin of our age.

Modern society and even some churches do believe that love is the ultimate parameter that trumps even the orthodox doctrines and practices that have stood for millennia. In fact, claims to truth are often in our times accused of being mere power plays to suppress other people, an act that, if this accusation is true, is the opposite of love. But in John’s thought, truth and love are inseparably wed. One cannot have truth without love, nor can one truly love without truth. For it is not loving to encourage someone to wander from the truth or to allow them to persist in the deception of sin.

We do not know precisely what was happening in the Johannine church(es) that motivated the elder to write such strong words, but it is clear that whatever it was, threatened the heart of the gospel (cf. Jude). It does seem clear that the pressing situation involved an errant Christology that rejected Christ as “coming in flesh” (2 John 7; cf. 1 John 4:2) and coming in both water and blood (1 John 5:6). It was apparently an example of Calvin’s claim that worldly people “do not therefore apprehend God as he offers himself, but imagine him as they have fashioned him in their own presumption.”10 And the world is full of such people today.

The Need for Discernment in a Pluralistic Age

Christians need to exercise discernment, and particularly Christian leaders who are the gatekeepers to our churches. At the same time, so much infighting among Christian leaders about things that are not essential to the heart of the gospel has taken the focus off those issues where truth is at stake. And when every issue is defined as a life-or-death struggle for the gospel, the force of the elder’s prohibition is blunted and the command to love others is violated.

One of the clearer issues today is the prevalent assumption that all monotheistic religions must be worshiping the same God by different names. This is an ecumenical impulse that reaches to embrace the world’s great religions—Christianity, Judaism, and Islam—into one brotherhood. While there may be common values and practices shared by these three (and other) religions, the NT example of a similar ecumenical impulse cautions us. When the Greek and Roman cultures met, each was worshiping a pantheon of gods and goddesses. In an ecumenical spirit to embrace the other, the pantheons were simply equated. “You Greeks call him Zeus and we Romans call him Jupiter, but it’s all the same.” However, when the apostle Paul encountered the Greco-Roman pantheon, he did not simply say, “The Greeks call him Zeus and the Romans call him Jupiter, but we know him as Yahweh or Jesus Christ.” To the contrary, Paul responded to the pagan religious zeal of his time with the rebuke, “turn from these worthless things” (Acts 14:15). And so we should be wary of too quick an application of monotheism that would, without nuance, equate the God of the Muslims and/or the God of the Jews with the Father of Jesus Christ.

Jesus Is Not Just Another Prophet

Christians also need to be wary of those religions who honor Jesus in some way, such as Mormonism, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Christian Scientists, but who have gone beyond the teachings of Christ by supplementing or revising the NT with religious ideas by much later thinkers such as Joseph Smith, Charles Taze Russell, and Mary Baker Eddy, respectively. These groups may well represent a modern instance of what the elder was arguing against in his time, for they emerged in the nineteenth century by deviating from orthodox Christian doctrine. To be clear, the elder’s prohibition does not give anyone license to be unkind or uncivil to coworkers, neighbors, or relatives who practice these religions. But the elder would prohibit us from endorsing their teaching, giving them a platform in our churches, or supporting them financially.

A case closer to home for Protestants is the Reformation. As the church developed from the ancient world to the medieval, the Roman Catholic magisterium, composed of the bishops and headed by the Pope, became the authoritative body charged with discernment and teaching. But when Martin Luther and other Reformers recognized the magisterium had gone beyond the teachings of Scripture in the sixteenth century, particularly on the issue of salvation, there was nothing left to do but disassociate.11

The unstoppable flow of history has brought, and always will bring, with it complex issues, intractable questions, and painful situations that confront Christ’s church. But in the midst of all this, true disciples of Jesus Christ in every generation must not lose sight of the elder’s main point: that truth has been revealed by God in Christ and that anything other than that brings spiritual destruction to those who embrace it. Belief about God is not mere personal preference, nor do all religions lead to God even if practiced sincerely. Thankfully the Spirit remains with us, the Spirit whom Jesus promised would guide future disciples into all truth (John 16:13). And the Spirit bears witness to the One who was born for the very purpose of bearing witness to the truth (18:37). Everyone who is “of the truth” will hear his voice, and in that promise the church’s future rests secure.