11

Moving Beyond 26.2

The Ultramarathon

Just because you crossed the finish line in your first precisely measured 26-mile-385-yard race, it’s not yet time to join Peggy Lee in asking, “Is that all there is?” There definitely is more, and the “more” is called the ultramarathon.

An ultramarathon (aka ultra) is any running race longer than 26.2 miles or 42.2 kilometers. For many, if not most, nouveau ultramarathoners, the next and logical step upward in distance is 50 kilometers, 50K, or 31.1 miles. A 50K is 5 miles longer than the standard marathon you may just have finished. It’s a much larger jump to the next round number, 50 miles (80.5 kilometers), but I have provided training programs for both the 50K and the 50-mile at the end of this chapter. The next rounded-off jump after that? One hundred miles. That takes a huge leap of faith: not quite climbing Mount Everest, but moving in the same direction.

Not all ultramarathons come rounded off. The world’s largest, oldest, and most prestigious ultra is the Comrades Marathon between Durban and Pietermaritzburg in South Africa. I use the word between because the race changes directions every year. Five massive hills separate Durban on the ocean from Pietermaritzburg inland. Heading to Pietermaritzburg, you go “up.” Return the following year, and you go “down,” although downhill miles are not easier than uphill miles unless you have trained your quadriceps muscles to resist the pounding. Because of the shifts in direction, the race distance fluctuates somewhere around 55 miles, or 89 kilometers. That seems appropriate, since for many ultramarathoners, it is not about distance, it is about meeting a challenge (like climbing Everest). The Comrades organizers don’t seem to worry about exact distances either, and why should they? Founded in 1921 in memory of South African soldiers killed in World War I, Comrades attracts twenty-five thousand runners each year; incredibly, entries are limited to that number. Comrades is like Boston in that there is a stiff qualifying standard. Boston has its BQ for Boston qualifier; Comrades has its CQ for Comrades qualifier. To get into this most ultra of all ultramarathons, runners must qualify by finishing an officially recognized marathon faster than 4 hours 50 minutes, that being the 2019 standard.

But most ultramarathons (as many as 80 percent, suggests Cory Smith of UltraRunning magazine) are run not on pavement but on trails that cut through the woods and onto desert sands, and even across rocky mountain ranges. Jason Daley ranked “The 9 Toughest Ultramarathons” in an article for Outside magazine, the toughest of the tough being the Marathon des Sables, a 6-day, 154-mile trek through the Sahara Desert in southern Morocco. Also on the Outside list was the Hardrock 100, which includes 33,992 feet of ascent and descent on its mountain course near Silverton, Colorado. Daley wrote: “Being above treeline for most of the course, racers are also vulnerable to lightning and freak storms.”

Despite the challenge offered by these extralong races, despite the extra miles seemingly needed both for training and for racing, participation in these longest of long-distance races seems to be in an uptick, at least based on runners signing up for my 50K program on the Internet: nearly a 30 percent increase between 2018 and 2019. UltraRunning magazine reports 2,129 races and 115,693 finishers in 2018. Two out of every three competitors are male.

A HISTORY OF ULTRAS

Those numbers seem stunning. Fifty years ago, you could count the number of 26-mile marathons in North America on the fingers of one hand. There was Boston, of course, the world’s oldest marathon, and Yonkers in New York and Culver City out in California and another marathon up in Canada, Saint-Hyacinthe. Maybe one or two others. One hundred fifty-one runners ran Boston in 1959, my first year running. No qualifying standard needed, and the entry fee was $1. Ultramarathons? You’ve got to be kidding. UltraRunning publisher Karl Hoagland identifies the JFK 50 Mile, started in 1963, as the oldest North American ultra. The race is still going strong with one thousand entrants a year. America’s finest ultramarathoner back in that era was Olympian Ted Corbitt, but he needed to travel to England to find a 26-plus race worthy of his talents. In 1965, I went to London on assignment from Sports Illustrated to report on Ted running the London to Brighton marathon, the world’s second most prestigious ultra at that time, second only to Comrades. Ted finished second. My article on that achievement eventually appeared in the second issue of a newly established running publication, Distance Running News, later to be renamed Runner’s World.

Nobody could have predicted how big ultramarathon running would become, doubling in the last decade. Hoagland believes part of the attraction is that “after you have done X number of marathons, the next logical step is an ultra.”

The training is tougher, the racing is tougher, but Hoagland points to the community spirit at ultramarathons, where people compete with themselves and with each other to overcome audacious, sometimes life-changing challenges. “In this troubled world,” Hoagland says, “ultramarathons have become a sanctuary from the storm by providing an epic experience in a positive and supportive environment that explores and celebrates the outer bounds of human potential. And it’s not just the racers, since the volunteers, crew, and pacers at 100-mile races put as much into the events as the runners. But they do so in some of the most scenic settings in the world.”

Adila Khazali of Kuala Lumpur agrees: “Ultras are a serious game-changer. For anyone who feels that their running game is boring these days, train for and run an ultra. It sounds crazy, but it’ll give you the experience of a lifetime.”

AND THEN THE VULTURE EATS YOU

Among my 111 marathons, may I confess, only two were run at distances beyond 26.2. Both my ultras, separated by several decades, were in South Africa. I ran well in the first, a 50K at altitude between Johannesburg and Pietermaritzburg. The second, Comrades, humbled me in that I failed to make the cut-off time that would have earned me a medal. A more important ultra on my curriculum vitae is the Trans-Indiana Run, a onetime event (not a “race”) that my running buddy Steve Kearney and I organized one summer almost as a lark, recruiting a total of ten participants mainly by word of mouth. Trans-Indiana covered the length of the state of Indiana “from river to shining lake,” the Ohio River to Lake Michigan, 350 miles in 10 days. I learned several important lessons during that run, held midsummer with temperatures in the 80s and 90s: (1) Proper (and specialized) training is essential; and (2) the vulture definitely will eat you if you fail to master your nutritional needs not only in the event but during the months of training leading up to the event.

Later, while researching this chapter, I wondered what training tips or tricks separated ultramarathoners from marathoners. What do ultramarathoners know that we shorter-distance runners have not yet discovered and perhaps never will? I decided to pose the question to my followers on Twitter. These were the strategies that I felt were most important:

-

More miles training

-

Good training program

-

Proper pacing

-

Nutrition before and during

The results of my Twitter poll were surprising (see the sidebar) in that only two percentage points separated all four strategies. The proper answer to my polled question appeared to be “all of the above.”

FOUR TIPS FOR ULTRAMARATHONERS

Let’s consider each of the four strategies:

1. MORE MILES TRAINING

When Ted Corbitt trained for ultramarathons, he often ran daily from his home near Van Cortlandt Park to his work (as a physical therapist) in Midtown Manhattan, 20 miles one way in the morning, 12 miles home on a slightly different course in the evening. This caused one individual hanging out on a corner whom Ted passed regularly to say, “Man, that cat’s late to work every morning.” Few runners I knew could have matched Ted Corbitt’s training mileages. During Labor Day weekend, while preparing for London to Brighton, Ted circled Manhattan Island (31 miles), then kept going on a second lap (62 miles total). But that was only Saturday! He then repeated that route on Sunday and Monday for a grand weekend total of 186 miles. On several occasions, according to his son Gary, Ted ran more than 300 miles in a single 7-day week.

But most of us are mortals, and that includes Angel Diaz of New Jersey, who followed one of my training programs for his first 50K in Philadelphia. A busy work schedule sometimes forced him to miss some runs, but not the most important runs: “I made sure I did my long runs no matter what. Aside from being honest about my training it was mainly becoming mentally strong.” So, “more miles training” does count.

2. GOOD TRAINING PROGRAM

Ultramarathoner Garrick Arends of Meridian, Idaho, favors quality training over high mileage. It is not entirely how many miles you run, Arends explains, but more how you run those miles. This was true with Steve Kearney and me as we prepared for Trans-Indiana. We did our long runs (plural) on two or more consecutive days, not just a single day. To that point, we might do a 2-hour run on Saturday followed by a 5-hour run on Sunday, running mostly on trails in Indiana Dunes State Park, not caring how much distance we covered, simply getting out and spending time on our feet. During the week, we ran fewer miles at slower paces so we would not arrive at the weekend too tired to train.

I recycled Trans-Indiana when I designed the 50K training program at the end of this chapter. Many ultramarathoners ignore distance, focusing on however long it takes to finish whatever distance they covered. For this reason, training for an ultramarathon is not necessarily tougher than training for a regular marathon. You get to pause for a drink without worrying that you are losing time. Racing an ultramarathon also may not necessarily be tougher than racing 26.2 if you heed the advice in the next paragraph.

3. PROPER PACING

I opened this book with the quick tip I often offered runners at expos the day before their marathons: “Start slow.” That sounds oh so simple, but it isn’t really. You need to control your pace, as Dan Lyne of Camas, Washington, explains: “It is essential that you learn how to run slow. If you’re only running 10 to 13 miles in a workout, it may seem you’re running too slow, but you’ll find out differently when you stretch those distances to 26, particularly in an ultra.”

Here’s a plus. Since most ultras, particularly the longest ultras on trails, are run at slower paces than marathons, you will lose less time if you shift, now and then, from run pace to walk pace—or even walk for long periods. Important: Don’t shift to walking pace only in races. Practice walking pace, and particularly practice shifting back and forth from walking to running pace. Don’t leave your run-walk-run strategies to chance.

4. NUTRITION BEFORE AND DURING

In speaking about marathon nutrition, keep in mind two words: Carbs rule! Fast-forward, if you please, to this page: “The Distance Runner’s Diet.” A proper diet for long-distance runners, I will explain, contains ample amounts of carbohydrate.

But…

And it’s a very big but. Not everybody agrees. Popular among ultramarathoners is the ketogenic diet, a diet high in fat (70 percent); somewhat high in protein (20 percent); but almost devoid of carbohydrates (10 percent). In contrast, I recommend a diet high in carbohydrates (55 percent) ahead of fats (30 percent) and proteins (15 percent). That’s the so-called Golden Standard, the diet I have followed most of my life.

Here’s the theory behind the keto diet: The body burns carbohydrates, which it turns into glycogen, quite efficiently. It is your rocket fuel. But if you limit carb intake while training for an ultra, you force your body to turn to fats for fuel. Burning fat requires more oxygen than burning carbohydrates. This “teaches” the body to more efficiently burn fats. Thus, in the 99th mile of a 100-miler, after the quickly burned carbohydrates have been consumed, keto supporters believe that the fats remain to speed you to the finish line.

However, in discussions with nutritionists, most specifically Nancy Clark, RD, author of Nancy Clark’s Sports Nutrition Guidebook and a fellow of both the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the ACSM, I haven’t come across any believable, scientific proof favoring fats over carbs, specifically for competitive athletes who train at high intensity. Nevertheless, among some experienced ultramarathoners, fats do rule. And if you have diabetes, the dietary rules for you are much different. If after a few marathons you want to experiment with a keto lifestyle, give it a try. Clark writes: “Each athlete needs to learn through trial and error during training and competition what works best for his or her body and what doesn’t work.”

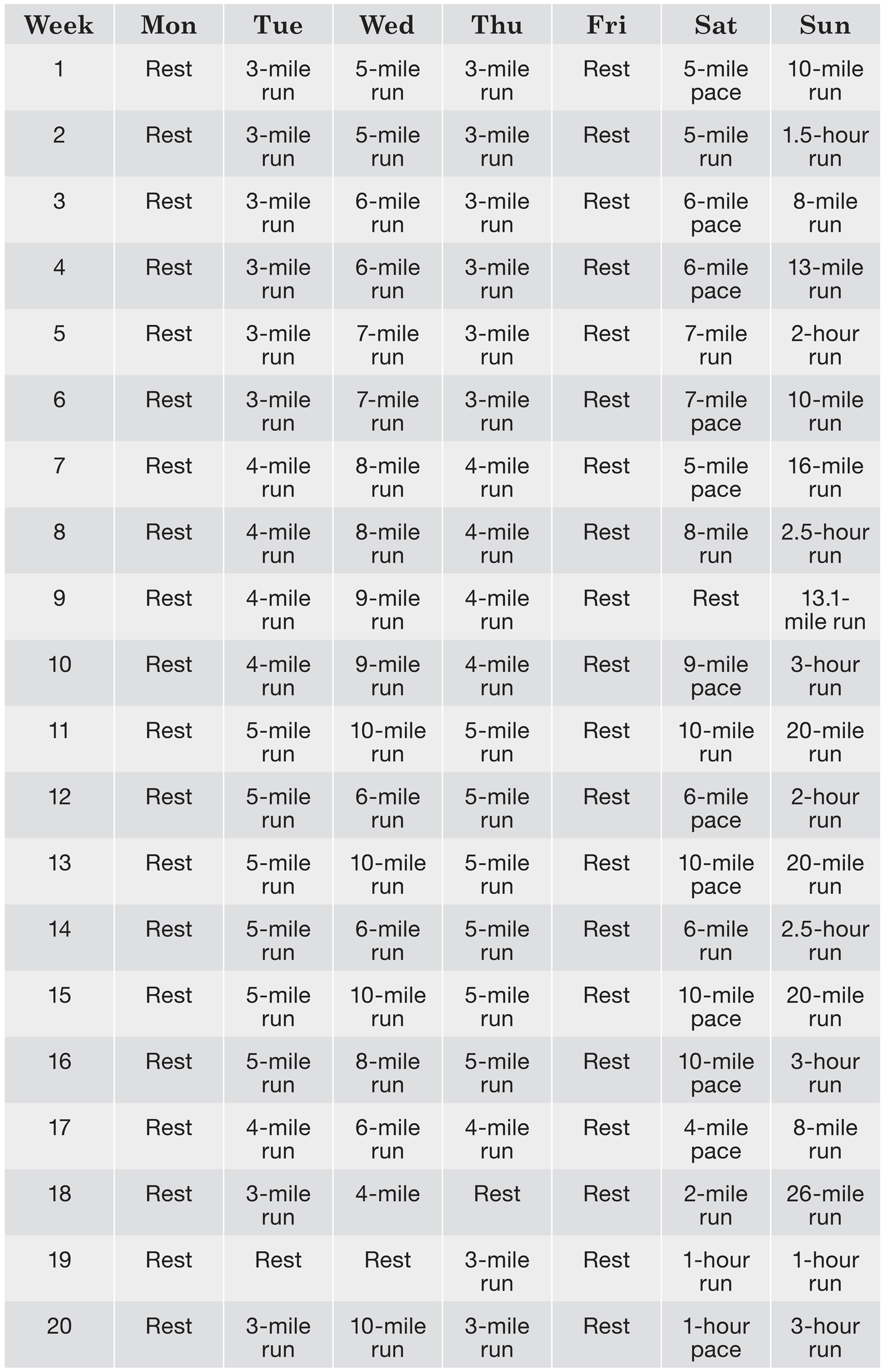

ULTRAMARATHON: 50K

Training for a 50K race is only slightly different than training for a 26-mile race. Unlike in my standard, 18-week programs, every other weekly long run is time-based rather than mileage-based. This is for psychological as much as for physical reasons. Three or more hours of running somehow sounds much more manageable than a specific distance. Since 80 percent of ultramarathons are run on trails rather than pavement, you need not know how far you ran (or walked) in any specific workout. One quick explanation concerning the difference between a “run” and a “pace” run. A run can be done at any speed, depending on how you feel that day; a run at “pace,” more specifically “race pace,” is a run done at the precise pace you want to hit in your goal race.

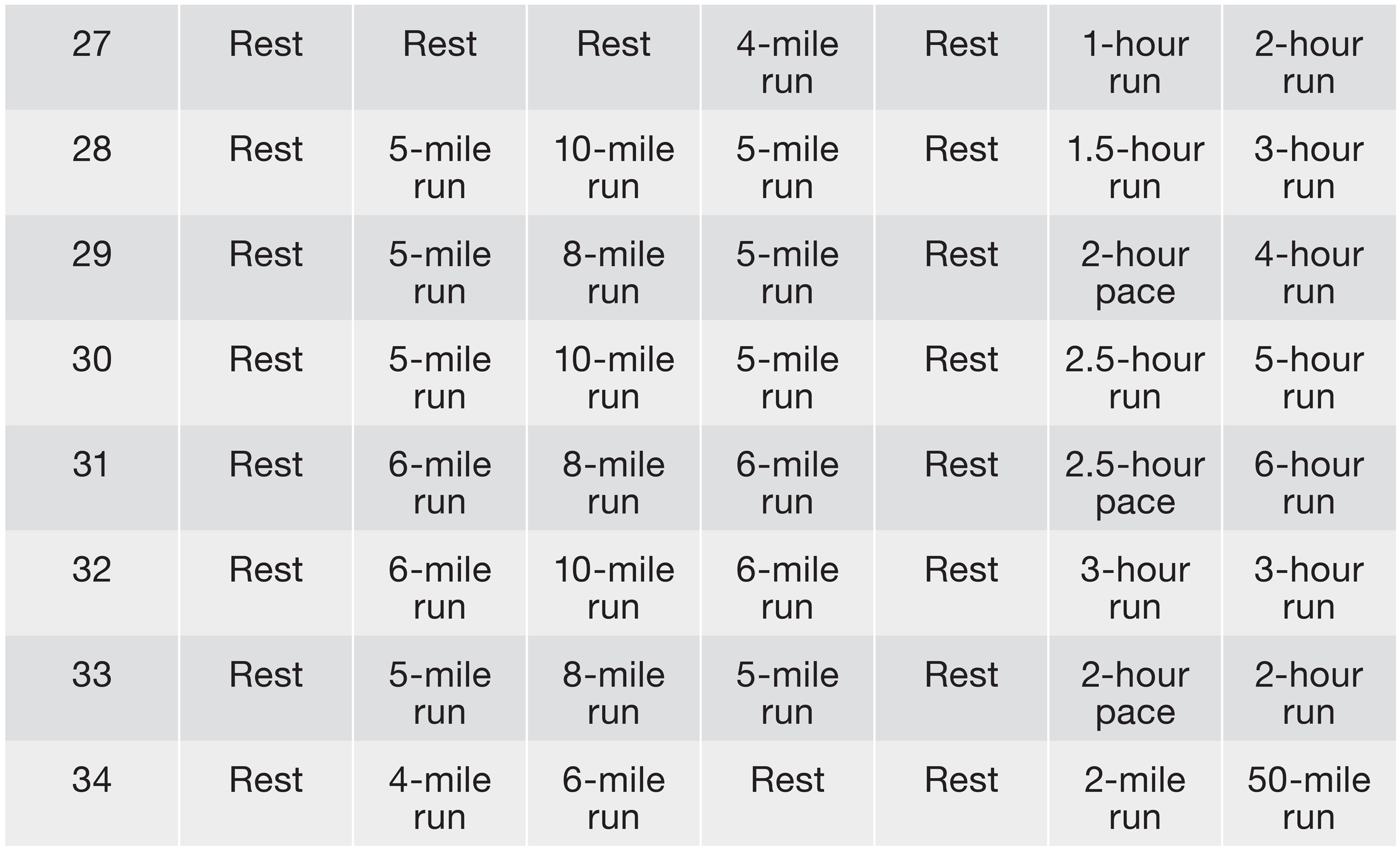

ULTRAMARATHON: 50 MILES

Nobody said making the jump from 50 kilometers to 50 miles was easy, but running ultramarathons is never easy, otherwise the challenge would not appeal to so many runners for whom 26.2 is not enough. To train for 50 miles, simply add the following 8 weeks of training to the 26-week 50K program. Note also that the 50-mile program suggests time-based training on both Saturdays and Sundays.

THE DOPEY CHALLENGE

Truth be told, the Dopey Challenge is not an ultramarathon, except in total miles run over four consecutive days at Walt Disney World: 5K on Thursday, 10K on Friday, a half marathon on Saturday and, finally, a full marathon on Sunday, close to 50 miles total. Yes, I suppose you have to be “dopey” to accept that challenge, but Dopey has proved increasingly popular among runners who also visit theme parks with their families between runs. The key to this program is to gradually, during a standard 18-week buildup, adapt your body to running on consecutive days. And (most important), don’t run so fast on the first few days and arrive at the fourth day with your energy stores drained. In addition to Dopey, a number of road relays (Hood to Coast in Oregon being the most popular) entice competitors to run multiple legs on multiple days. This Dopey training program can serve as a pattern for such races. Week 1 offers a 13-miler. Does that seem far for you? If so, maybe you are not Dopey enough to accept this challenge.