On a frigid morning in 2012, I donned a plastic hard hat, pulled a fluorescent-yellow vest over my parka, and was admitted to the vast, swarming pit of the World Trade Center*1 site. A crane swooped down to pluck a steel beam from a flatbed truck and reel it into the air, where it dangled like a plastic prize in an arcade game. All around, workers in color-coded vests and hard hats clambered over various quadrants of the site. In one vast hollow, steam shovels spooned away soil. In another, a naked steel cage was rising above a pick-up-sticks pile of conduits, subway tubes, train tracks, truck ramps, and interlaced foundations.

I stepped into a hoist clamped to the side of Tower One. It was a worrisomely low-tech method of transportation—no more, really, than a steel-mesh box lined with plywood and warmed by an electric blower. A dozen bulky men packed in around me, their voices booming and torsos thickened by layered sweatshirts, flannel, and fleece. The operator clanked the gate shut and we lurched upward. I got out on the ninetieth floor, then still a raw concrete slab topped by a thatch of bare columns and rebar. Someone had torn a hole in the netting that wrapped the exposed floor, framing the vista. Down below, the city seemed to be floating away, barely tethered, hardly real.

At the center of the structure, two cranes raced each other to the sky. A battalion of lathers, ironworkers, and welders lit the scene with blowtorch sparks. One man gripped a thick iron rod that another banged with a sledgehammer. It looked like a scene from some medieval illustration of labor—“The Blacksmythe’s Forge.” For no discernible reason, one of the workers lifted a cry of “whoo-whoo.” Another answered him from across the slab, and soon dozens of men were hollering, filling the air a quarter of a mile above Manhattan with a primal group yodel. Then it died out, whipping away on the cold wind. When it was time to go, an older worker whose hard hat was entirely covered by a patchwork of American flag and 9/11 memorial stickers picked up a length of rebar that was lying on the floor and slammed it noisily against the hoist’s metal frame to summon the operator. “Yo, Vince,” he bellowed down into the void. “We got tourists.” He let the iron bar bounce on the freezing concrete and marched back off to work.

9/11 Memorial Museum pavilion, with the transit hub and plaza reflected in the façade

As I thawed out on the way down, I felt that I had witnessed an unfathomably complex feat of craftsmanship, carried out on a pharaonic scale. This sleek technological marvel, where hushed offices would one day be as carefully lit and temperature-controlled as cases in a museum, was being hammered together by hand, like a Gothic cathedral. I was also watching emotion harden into form. The man with the stickers on his helmet was just doing his job up there in the icy air, but he was also helping to bring order to chaos, a mission that, like many construction workers, he may well have begun in the toxic rubble of September 11, 2001.

Twin Towers

For years, I stayed away from reminders of 9/11 and the weeks that followed. The most exhaustively recorded cataclysm in history yielded fictionalized movies, documentaries, YouTube clips, eyewitness accounts, TV news reports, police-radio tapes, and endless documentation. I avoided it all. Instead, I remained focused on the drama of reconstruction, returning to the site over the years to observe swarms of welders cauterizing the urban wound. I watched as the messy tangle of history and ganglions of infrastructure were covered over by a great concrete quilt and thin sheets of glass. Today, the site’s subterranean realm serves overlapping but incongruous functions, few of which are visible from the street. Trucks enter a buried ramp where security agents can scan them for explosives. Subway and commuter trains click through their concrete tubes. And in a crypt seventy feet below street level lie some unidentified human remains.

The World Trade Center was never just another construction project, though at times it behaved like one. Those who followed it grew accustomed to a steady drip of frustrations. The list of delays, petty grievances, bastardized designs, exploding budgets, and truncated ambitions is too lengthy and depressing to rehash. The result is, on the surface, at least, a geyser of unflappable corporate modernism, a monument to business as usual. Walking through the vast campus now, you might be fooled into thinking of it as the acme of rational design. The symmetrical, supertall Tower One rocketing skyward; the artful arrangement of prisms that makes up its much smaller but still colossal neighbor, Tower Four; the memorial’s rectilinear voids—the whole complex exudes geometric cool.

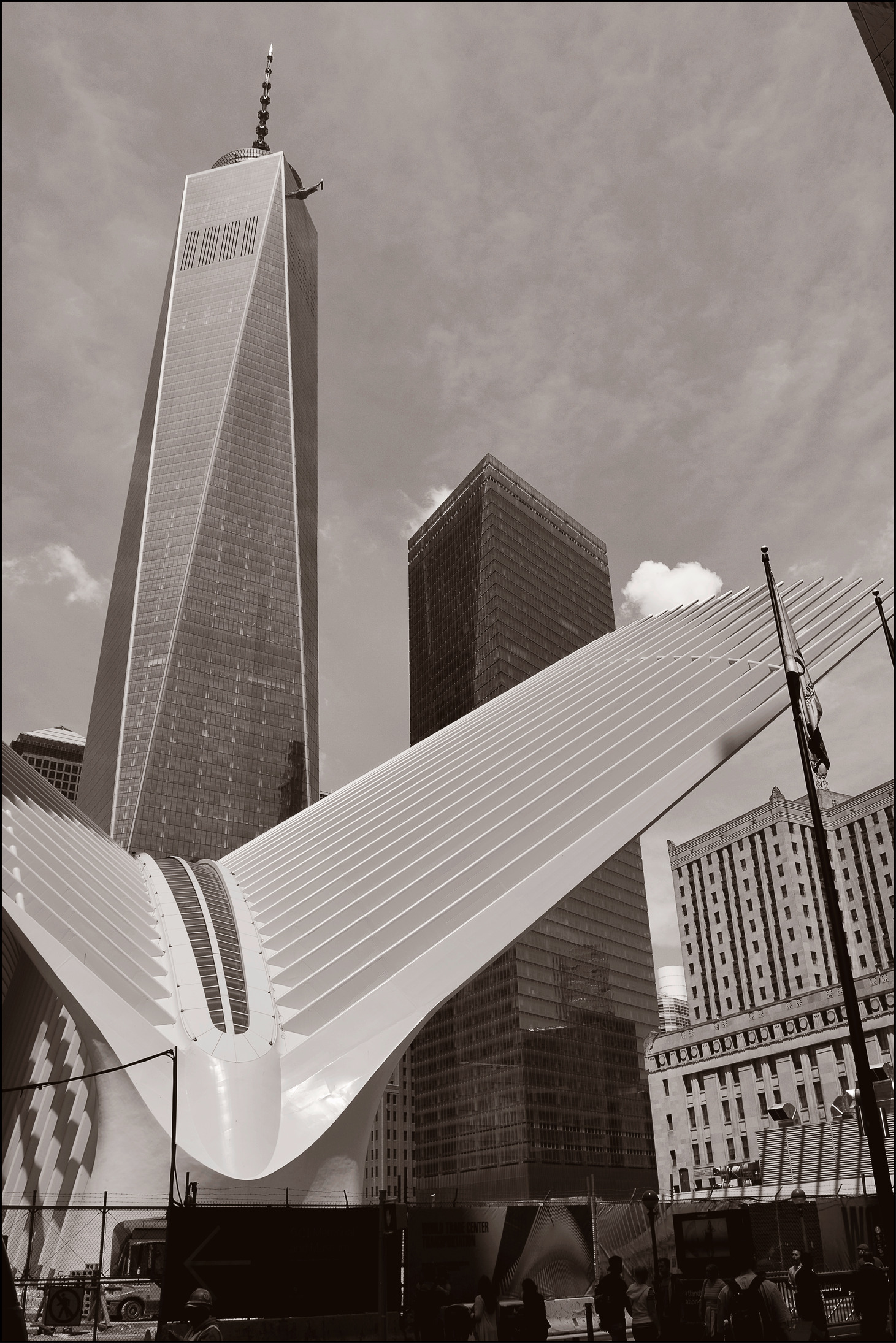

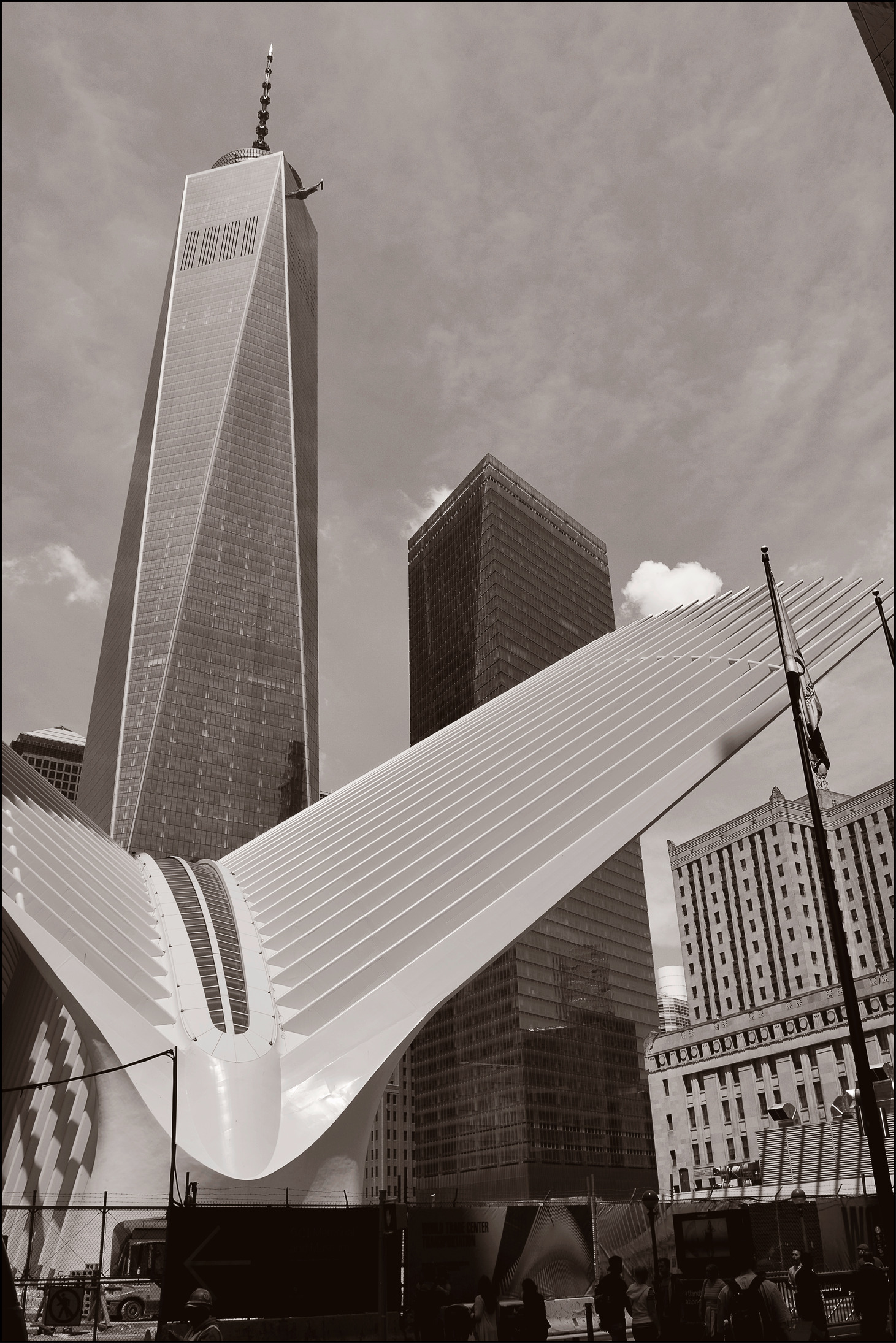

The 1,776-foot One World Trade Center, with the crouching transit hub

When those buildings first started to rear up, shining, from the mire, the surprise was how much optimism they broadcasted. A year after my winter visit, Tower One had evolved into an immense festive skeleton arrayed in multicolored lights, like some kind of mutant lawn ornament. On stormy days, the wind literally howled through the open floors, producing an unearthly shriek that could be heard for blocks. The building was still raw, hopeful, and wild. The World Trade Center isn’t just an achievement of government-subsidized capitalism or sophisticated engineering; it’s a collection of enshrined feelings. Fear and defiance gave us the bulked-up skyscraper whose height of 1,776 feet, back when it was called the Freedom Tower, was determined not by any market or structural considerations but by the master planner Daniel Libeskind’s penchant for historical symbolism. Preserved grief produced the memorial. The white, winged Transportation Hub embodies the need for uplift that fifteen years ago even hardened pragmatists craved. The horrific pit has been filled in, built up, and dressed in a palette of steel and pewter and charcoal and slate, a whole range of blacks and grays accented by reflective surfaces. Healing, denial, and commemoration battled for primacy and reached an uneasy equilibrium.

Maybe the results were bound to disappoint. The architecture of this site had to perform so many contradictory tasks—notably, to honor trauma while allowing business to continue as if nothing had happened. A multibillion-dollar complex of skyscrapers can accomplish many things, but it’s not very good at dealing with paradox. Despite its complexity, the new World Trade Center has two distinct realms: above and below, work and remembrance. The first demands a purposeful amnesia, the second an unyielding commitment to the past. When the office towers are all built and filled and humming, the tens of thousands who swipe their ID cards in the turnstiles each day must persuade themselves to forget the mayhem and the enduring threat. You can’t make money in a graveyard, or on a battlefield.

When I next visited Tower One, it was nearly ready for tenants. I made the ascent indoors this time, in one of the warp-speed elevators that beam workers up to their cubicles from the white portal of the lobby. Now, instead of wind-scoured slabs of concrete, I found office floors soaked in daylight. The curtain wall’s thirteen-foot panes of glass made the interiors vertiginously airy and gave the exterior an almost liquid seamlessness, as if the façades were coated in shellac.

Today, those offices contain the hum of work getting done, deadlines being met, approval being sought. It is a hive of mundane anxieties, designed to minimize historic drama, to make everyone forget the circumstances of its birth and the threats it guards against. The almost $4 billion skyscraper, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), tries to balance brawn and poise. Like the original Twin Towers, the structure is a rectangular block, only here each corner has been shaved away so that the building tapers from square base to smaller square top, passing through a series of octagonal floors.

There’s a lot of mild deceit embedded in this building. Employees of the publishing conglomerate Condé Nast, the tower’s first marquee tenant, can approach along a newly extended Fulton Street and enter through a handsome sheet of glass, as if this were just any corporate building. But the lobby doesn’t open directly onto the street; it takes cover behind a blast barrier and backs onto an elevator core built as solidly as the Hoover Dam, with ultra-dense concrete six feet thick. The designers have made an attempt to cloak all the armor, but the message is clear: No soft targets here; anyone with malicious intentions should just keep moving right along.

The tower is unpeopled at the bottom and the top. The base is a massive concrete bunker, impervious to all the threats that the police department could think of. SOM has tricked out the first twenty floors of the façade with the architectural equivalent of rhinestones: pairs of glass fins, cocked at different angles and illuminated from behind, so that the surface glitters twenty-four hours a day. Inside, the lobby has an inadvertently sepulchral air. A collection of gaudy paintings struggles to enliven the high white walls, illuminated niches, and pale angelic light wafting down from above, but the effect remains subtly morbid.

There’s more razzle-dazzle up top. The building proper rises just to the height of the original World Trade Center (a mere 1,368 feet), but it’s capped by a 408-foot spire, the principal purpose of which is to win the title of tallest building in the Western Hemisphere. (And it did, after a lively debate in height-certifying circles over whether the mast qualified as an architectural element or just a piece of broadcasting equipment stuck on top.) What a strange griffin of a building, with its bulked-up base, its lean glass torso, and its elaborate ceremonial headgear.

Nowhere is the tension between buoyant gleam and gnarled history starker than in 4 World Trade Center,*2 the tower by Maki and Associates. It’s the epitome of the office building as gadget. The out-of-the-box sheen, corners sharp enough to shave with, surfaces so smooth and pristine that a fingerprint reads like graffiti, lines you could sight a rifle by—every detail and finish is calculated to stimulate pride (if you belong there) or envy (if you don’t). The elevator hall’s marble isn’t just white; it’s frothy and unblemished, as if Maki had skimmed off the cream of the quarry and discarded everything else.

To what end, this fetishized perfection? Maybe it performs the same consoling magic on the site’s violent history as do hospital corners and gleaming uniforms: It neutralizes gruesome memory, substituting violence with order. From the upper floors, you can press yourself against the glass and squint past your feet to the memorial below. At the end of the workday, you step across the granite-paved lobby, slip through the glass membrane, and emerge onto a block of Greenwich Street that the old World Trade Center had obliterated and that has now been restored. Cross that, and you come to the memorial plaza and the pair of dark-polished wells of melancholy.

Soon after the Twin Towers fell, the young architect Michael Arad made a dreamy sketch of two square holes in the Hudson River, with water perpetually flowing in from all sides. That poetic image, haunting in its impossible simplicity, evolved into the entry that won the design competition for the 9/11 Memorial.*3 Later, Arad’s imaginary sculpture of water and air (transposed to the site of the original towers) materialized into a pair of chasms clad in granite the color of shadow and then lined with a film of falling water. Inside each box is a second void, its bottom always out of sight. Names, incised in bronze, scroll around the lip of that austere vastness. The two pools share the same mournful shade, form, and dimensions but bear different roll calls of the dead.

The memorial plaza isn’t an especially solemn place, most of the time. Families come to pay their respects and, having done so, aren’t quite sure how to sustain an attitude of sobriety. Office workers stroll by, hollering into mobile phones. Tourists pause on granite benches to plan their next stop. Teenagers take selfies with the names carved in bronze and the big shiny towers beyond. The atmosphere is a mixture of uneasy reverence and casual cheer. That’s all as it should be. The plaza, with its hard pavers and soft canopy of oaks, was always intended as a verdant buffer between the temple and the street. It’s okay that the impeccably tailored corporate design should gloss over the past and hide the saga of destruction, dismantlement, and rebuilding. For years, it was a no-go zone, cordoned off and largely invisible. Visiting the memorial plaza—something New Yorkers hardly did—meant obtaining passes and standing on line for airport-style security. Now that the fences have come down, crowds are once again flowing freely.

This might have been a far richer, greener public space if it hadn’t immediately been co-opted by symbolism. From the beginning, bringing this part of the city back to life meant consecrating a big chunk of it to death. The emotions that followed the attacks—apocalyptic foreboding, looming grief, panic, determination, and the obsessive fear that memories would fade along with the state of emergency—imprinted themselves on the city in an oversize, irreversible way. Future New Yorkers will not share my generation’s feelings, but the pair of geometric fissures in the middle of dense downtown will keep admonishing them that they should. Already those who barely remember and those who hardly knew stare down into the infinity of one pool and hear the exhortation “Never Forget.” Then they walk over to the other and receive the message a second time.*4

The design’s basic, ineluctable elements were already laid down well before Arad sent in his drawing. In January 2002, Monica Iken, a victim’s wife, asked at a public meeting: “How are we going to honor those like my husband who died? How can we build on top of their souls that are crying?” That demanding expression of grief became an explicit political agenda a few months later, when then-governor George Pataki echoed Iken’s demand that the lots where the Twin Towers had stood be dedicated to commemoration. The buildings’ footprints, 212 feet on every side, “will always be a permanent and lasting memorial to those we lost,” he promised, declaring them “hallowed ground.”

By the second anniversary of the attacks, as the memorial-competition jury was sifting through thousands of proposals, the president of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, Kevin Rampe, made the exclusion even more specific and categorical: The footprints of the two vanished towers, he declared, would remain free of commercial structures “from bedrock to infinity.” A few people wondered whether it was wise to plan a memorial while the pain was still fresh, before trauma had hardened into history, but it was already too late for equivocations. A succession of vows had already defined the memorial’s shape, size, and location, plus its overriding aesthetic of emptiness. (The openings are in fact slightly smaller than the Twin Towers’ footprints, but a tree was placed on the plaza directly above the stump of each supporting column, reproducing the original perimeter in symmetrical greenery.)

The site’s master planner, Daniel Libeskind, initially conceived of the memorial as an eight-acre park dropped seventy feet below street level. (He later pulled it up to less than half that depth.) Arad wisely feared that such a plan would produce a grim pit in the middle of a space-starved neighborhood. What he wanted instead was a grand piazza at sidewalk level, where the city’s life could churn around separate zones of mournful pensiveness. Those he envisioned as a pair of sunken cloisters, reached by ramp from the plaza, and a gallery running around the perimeter of each square, curtained by falling water. I can imagine that walking through such a space might have had a mellow beauty: shadowy towers and mottled light visible through a liquid veil, and the city’s clangor softened by the fountain’s steady thrum. But the idea of bringing visitors into the depths and communing with the names below ground, so central to Arad’s conception, was tossed out, on practical and financial grounds.

Arad’s clarity of vision did not exempt his project from the thicket of bureaucracies, budgets, rules, security fears, agendas, and political interests that dogged virtually every step of the redevelopment. The history of squabbles over how to arrange the names of the dead, for example, is not an uplifting tale. Still, Arad claimed that this grinding process wound up enriching his design. It’s true that the simple squares are vibrant with understated detail. The names are not just carved but cut right through a thick bronze plate, the letters made of space and light. Water flows through channels spaced an inch and a half apart, forming separate filaments that merge as they fall. The dark granite of the fountains sets off the pale-gray pavers on the plaza, which alternate in rough cobbles and smooth planks of the same stone. The trees are planted in irregular rows that look random at first and then suddenly snap into orderly allées.

The fountains have a separate pedigree. They evoke the work of the earth artist Michael Heizer, who, at around the time the original World Trade Center was going up, sliced a deep wound in a Nevada desert and called it Double Negative. But the closest precedent to the 9/11 memorial is Heizer’s North, East, South, West, an ominous set of cubical and cylindrical steel voids sunk into the floor of the Hudson Valley museum Dia:Beacon. Arad has merged Heizer’s rough morbidity with tailored elegance. His huge cubes of nothingness—Arad’s own double negative—take their place among the pin-striped canyons of steel and glass. Mid-century modernist architects fetishized such orthogonal precision, and their spiritual heirs—the ones producing all those tight-cornered office towers—still rhapsodize about the elegance of a straight line and a flawless edge. Ultimately, Arad’s memorial belongs in their company more than in Heizer’s, because he subordinates heroics to fastidious detail. In the end, the memorial winds up looking like a massively enlarged version of an antiseptic corporate plaza.

Designing the memorial*5 was the first act in the drama of commemoration, but it occupies only a part of the void left by the destruction of 9/11. Part two is the 9/11 Museum, an even grander, more ambitious epic of memory.

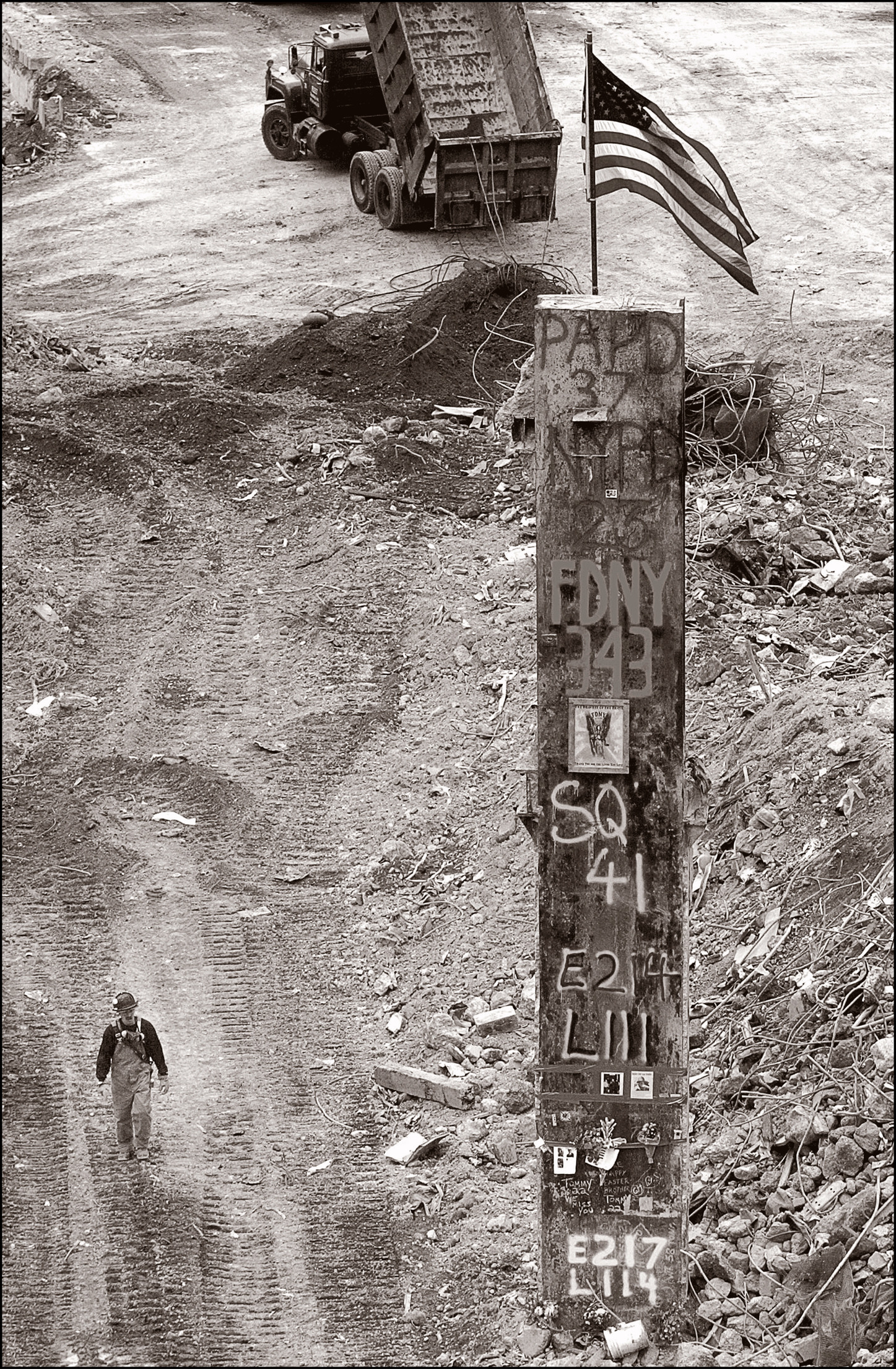

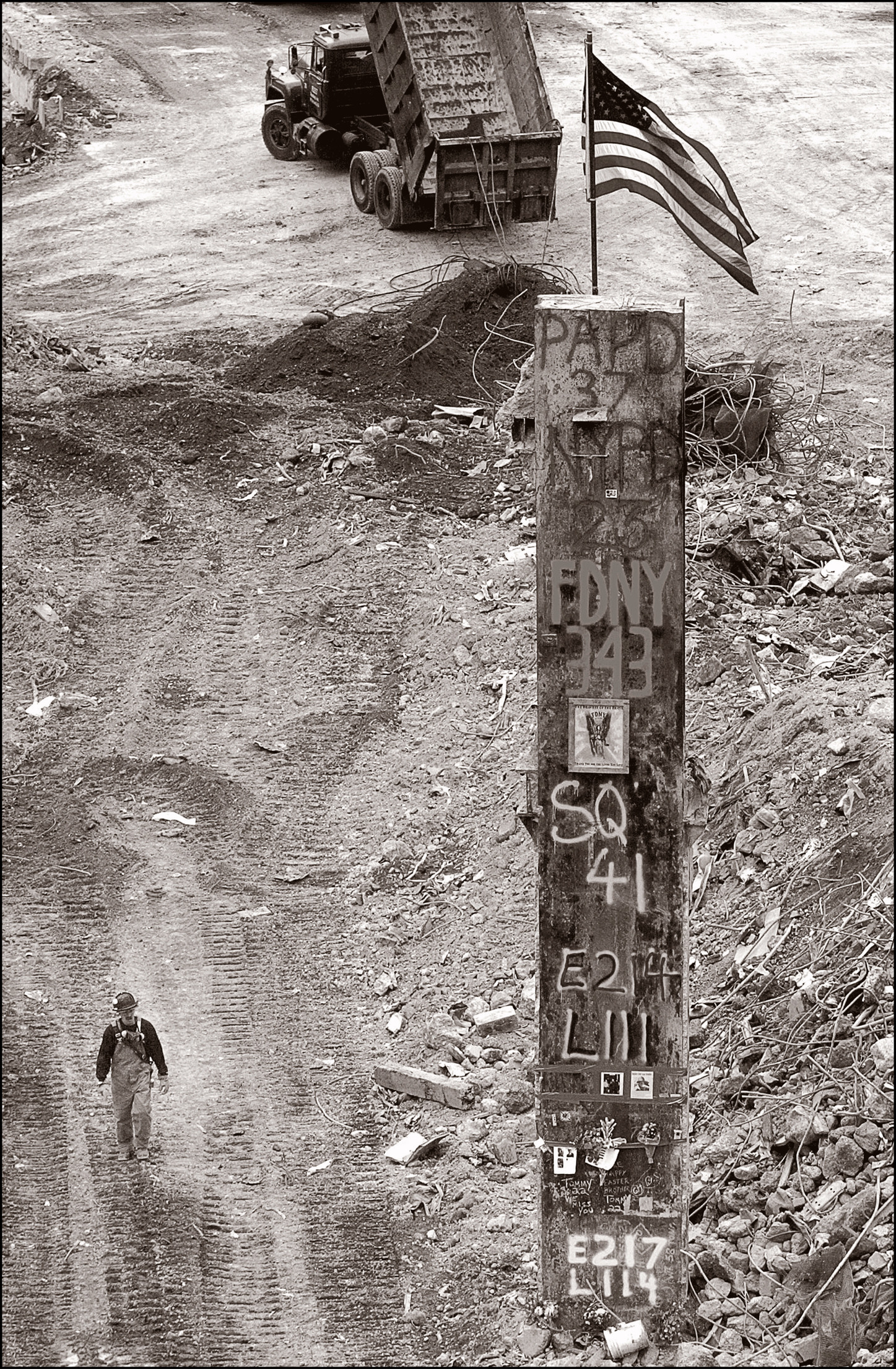

The last column standing at Ground Zero

In late May 2002, the place they still called Ground Zero had become an immense and pristine hole. Truckload after surreal truckload of mangled steel and ash and gruesome finds had been carted away, leaving a flat expanse of concrete and rock. One final column from the Twin Towers remained standing, a thirty-six-foot totem of rusting steel emblazoned with cryptic notes, duct-taped snapshots, and a running tally of recovered bodies. But even with the cleanup declared done, workers kept raking the floor with ordinary garden tools, hunting for some infinitesimal shard of human bone. Today, the floor, the column, and one of those rakes are reunited in the museum, a huge and spectacularly painful institution slipped below the memorial fountains.

I had an early preview of what a museum might be like a decade ago, when I visited Hangar 17 at JFK Airport. There, crushed emergency vehicles, twisted girders, sections of the antenna, half a dozen bikes still chained to a rack, and a lump of fused metal, concrete, paper, and glass were all laid out in an improvised architectural morgue. The last column lay on its side, housed in its own dehumidified area. I found the hangar tour draining but also strangely reassuring. If the authorities treated all this detritus with such reverence, maybe one day the public would, too. Years later, though, the prospect of revisiting that archive of mass murder relocated to its place of origin made me fibrillate with dread.

The museum is buried beneath the crime scene. I enter through the silvery pavilion designed by Snøhetta, which has the pale sheen and fractured lines of a glacier in mid-melt. Daniel Libeskind had once imagined that the entire sixteen acres would have that icy, falling-apart look; this is a fragmentary remnant of that vision. As visitors line up outside, they can peer through the glass wall to the only traces of the ruined behemoths that penetrate above ground: two of the linked tridents that formed the towers’ Gothic arches. Weathered but unbent, they thrust vertically past their new home’s weave of angled struts, mute reminders of the original buildings’ enormity. They also stand as signposts to the Stygian galleries below.

As I enter, I wonder where the museum experience will fall on the spectrum from anodyne to earnest to brutal. Virtually every decision in this enterprise has been controversial: the underground location, the inscription from Virgil’s Aeneid (NO DAY SHALL ERASE YOU FROM THE MEMORY OF TIME), the ticket price ($24), the gift-shop souvenirs, the placement of unidentified human remains in an inaccessible chamber just off the museum’s main hall, the inclusion of terrorists’ photographs, the short film about the rise of Al Qaeda, and so on. The more I think about the task of perpetuating the recollection of that day, the more doubts flock: How can a museum chronicle unsettled history or interpret an event we don’t fully understand? How can an exhibit be meaningful to those who were showered in ash that day and also to children yet to be born?

I walk down the long staircase into the minimalist Hades designed by Davis Brody Bond. A murmuring choir of recorded reminiscences from all over the world reminds me that 9/11 was a global event. The dark floors and austere aura make me wistful for the light above, but the architects have taken care to lead visitors gently into the depths. Underground spaces can be disorienting, but this one comes into partial focus at the first overlook. Shock arrives in ripples of recognition. A ramp winds down toward the foundations, where the cut-off columns that held up the Twin Towers sit embedded in Manhattan schist. A pair of building-size boxes containing the memorial’s waterfalls and coated with glistening aluminum foam hang in the immense cavern like geometric stalactites. I have arrived at bedrock level, the floor of the concrete bathtub, separated from the Hudson River by a seventy-foot-high section of “slurry wall” so brawny and raw that it feels like the remnant of an ancient Mayan temple. It’s here that the collapsing skyscrapers came to rest.

The tale that this museum has to tell is partly about dimensions—the inconceivable scale of murder, the size of the weapons, the sheer bulk of the targets, the worldwide aftershocks. Doing it justice requires a lot of space. As I stare at thick girders bent by the force of a speeding plane, I try in vain to conjure up the extremes of violence that formed it. The last column is standing upright again, proud and solitary in the great hall just as it was in the open pit—only now a touch screen allows visitors to zoom in to the scrawls and taped mementos and to read a digital text label for each one. After all, a museum’s job is not just to preserve but also to explain.

In 2006, Alice Greenwald, who had been a director at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., was appointed to run what was then an amorphous institution with a laundry list of topics and a backlog of acrimony but no overarching concept, no consensus, no design, and not much of a collection. So Greenwald launched a series of exploratory powwows. “We brought everybody into a room,” she says, “family members, survivors, first responders, landmark preservationists, architects, museum people—and we started with a set of very large questions about what a museum should be.” From those conversations, the team arrived at a few fundamentals: that immense spaces should contrast with intimate chambers, that visitors should be free to create their own itinerary and bypass whatever content they chose, and that tissue boxes would be strategically placed.

The result is a bifurcated museum, split between the square footprints of the original towers, its two parts tucked beneath the twin memorial pools. Where the South Tower stood is the memorial exhibition, an outer room papered with the photographs of the 2,977 people killed on September 11, plus the six who died in the World Trade Center bombing of 1993. Table-mounted touch screens bring up details of the victims’ lives, which can be projected on the walls of a separate room, an inner sanctum where the lost are remembered one at a time. In an audio recording, the Cantor Fitzgerald employee John Katsimatides’s sister Anthoula teases him posthumously about his John Travolta dance moves: “They used to call him Johnny Bodacious,” she recalls.

Beneath the North Pool, stowed in a climate-controlled zone behind glass doors, the historical exhibit is a tour de force of devastating authenticity. Its core is a minute-by-minute timeline of the events as we all observed them, starting at 8:46 A.M., when the first plane hit. In the confined spaces of the exhibition, you confront the experience of a city blasted beyond recognition. Firefighters, their landmarks, equipment, and buddies all gone, mill helplessly around, then start to search through the great pile for tiny caves where someone might conceivably have survived. Almost subliminally, the design leads you from small spaces to large, toggling between intimacy and awe.

Chief curator Jan Ramirez assembled a collection of mundane objects and digital traces sanctified by circumstance. We see the wristwatch that Todd Beamer, a passenger on Flight 93, was wearing when he muttered, “Let’s roll,” into an open cellphone, then organized a doomed rebellion against the hijackers. (The plane crashed into a Pennsylvania field.) We hear Sean Rooney call his wife, Beverly Eckert, just after the first plane hit to reassure her that the problem was in the North Tower and that he was fine. (He died.) We read a letter from Kenneth Feinberg, special master of the Victim Compensation Fund, informing Steven Morello that his father’s life was worth exactly $62,135.41. We imagine the sensation of strapping on the Phantom of the Opera–like burn mask that Harry Waizer, who’d worked for Cantor Fitzgerald and was badly disfigured by fire, wore sixteen hours a day for a year after the attacks. We stare at a sealed store window, where jeans and sweatshirts coated in toxic ash form a wrenching diorama. These artifacts, too, reflect the scale of September 11, which didn’t just rip a hole in history but also stole into separate lives.

The task of weaving photos, audio, video, and radar into narrative fell to Thinc, the exhibition design firm headed by Tom Hennes, and Local Projects, a multimedia design company founded by Jake Barton. This was the aspect I worried about most—that glossy screens and hyperactive graphics would distract from the experience they were supposed to enhance, or else not work at all. That danger isn’t past—it’s crucial that the machines are maintained with fanatical perfection—but the use of interactive technology is tastefully restrained. There are films but no sonorous narration, no added sound effects—just, as they say, the facts. The graphic palette, like the architecture, is mostly black and white. Every one of the interactive displays must strike a balance between vividness and consoling distance, and when they don’t get it right, they err on the side of aloofness. “We don’t ever want to re-create that day,” says Tom Hennes of Thinc. “It’s not about screams and sirens. You’re at the site, but you never lose sense of the fact that you’re there today, not back then. The there and then of the day comes through testimony, not immersive experience, which would be sensationalizing and exploitative, and potentially traumatizing.”

At times, the sensitivity becomes glaring. A wall label near the entrance to one alcove states the stunningly obvious: PLEASE BE ADVISED THAT THE PROGRAM CONTAINS DISTURBING CONTENT. That description gets ratcheted up to “very disturbing” in the corner reserved for the topic of those who, faced with the choice between burning and jumping, chose the open air. I couldn’t face that section on my first visit, but on the second I steeled myself and went in, to find familiar horrors: no videos or identifiable faces, only stills of distant plunging specks.

The museum averts its gaze in more insidious ways, too. The story that opened on a bright Tuesday morning at the start of the school year kept growing more tendrils. During Alice Greenwald’s first year on the job, construction began on One World Trade Center, Saddam Hussein was sentenced to death, the war in Afghanistan raged, and drone strikes became an almost daily routine. The meaning of 9/11 continues to change, which means that the museum must be simultaneously definitive and open-ended. “We’re a museum that doesn’t presume to wrap it up nice and neat,” Greenwald says.

In fact, it presumes too little. The exhibits hint at the complexity of the aftermath without tackling the thorniest topics. There are glancing references to conspiracy theorists and tensions between security and civil liberties. A gimmicky digital synopsis projected on a wall keeps recomposing itself, creating a new sequence of headlines every few minutes, but it all goes by too quickly to digest. Clips from on-camera interviews with dignitaries are interspersed with comments that visitors can contribute in a recording booth. But we learn little or nothing about torture, or rendition, or Abu Ghraib, or Tora Bora, or drone raids on Pakistan, or the Bush administration’s spurious linkage of 9/11 and Saddam Hussein to justify the war in Iraq. We are spared Rudy Giuliani’s constant campaign invocations of his leadership in the wake of 9/11.

As I thread my way through the skein of memories and outrage, it occurs to me that mine is the reaction of someone who was in Manhattan on that day. I am discomfited and unhappy—and that is the museum’s strength. It’s a tonic for the jaded and an antidote to denial. To visit is to volunteer for certain but tolerable pain. I wonder, though, what impact the museum will make on my son, who spent that morning happily playing dress-up on his first day of preschool, or what it will mean to his grandchildren. Hennes has thought about that question, though he offers no pat answer. “People will enter this place with all different narratives. There isn’t one story of 9/11. There are thousands. The museum has to be a place where those stories can be told, and where they can be made coherent.” But history is not, or not only, a subjective affair, and the museum’s lasting power lies in the unadorned presentation of evidence. In one alcove, recorded voices from inside the towers segue one into the other, while illuminated pinpoints on a simple diagram indicate the speaker’s position. We hear Orio Palmer, a fire department battalion chief who has climbed to the seventy-eighth floor of the South Tower, shout breathlessly into the radio to report “numerous 10-45s Code Ones”—fire department lingo for the dead. The realization that he will be next comes in a burst of weird, appalling immediacy. We are witnessing the instant of doom from the comfortable distance of time, and it’s still not easy to bear.

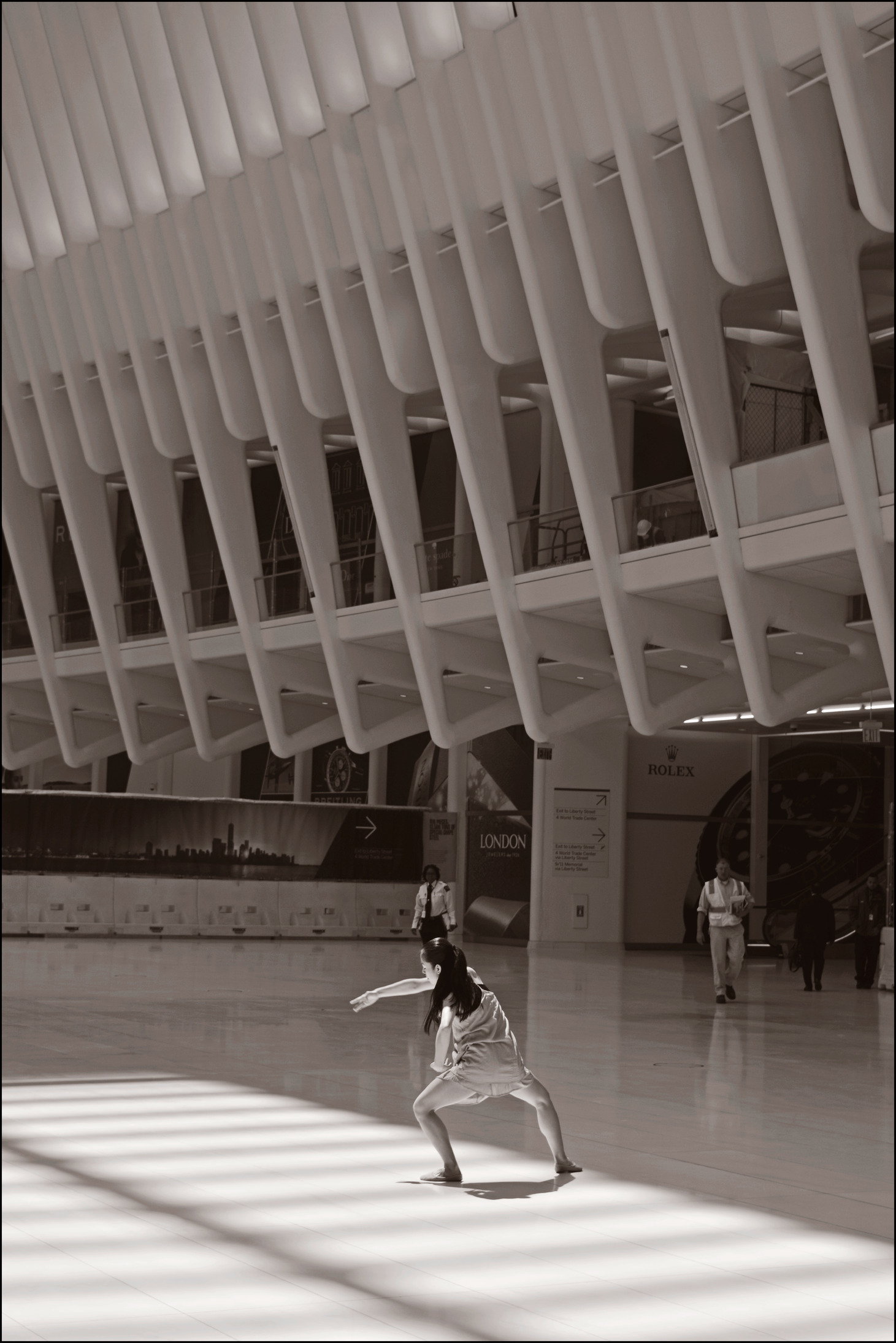

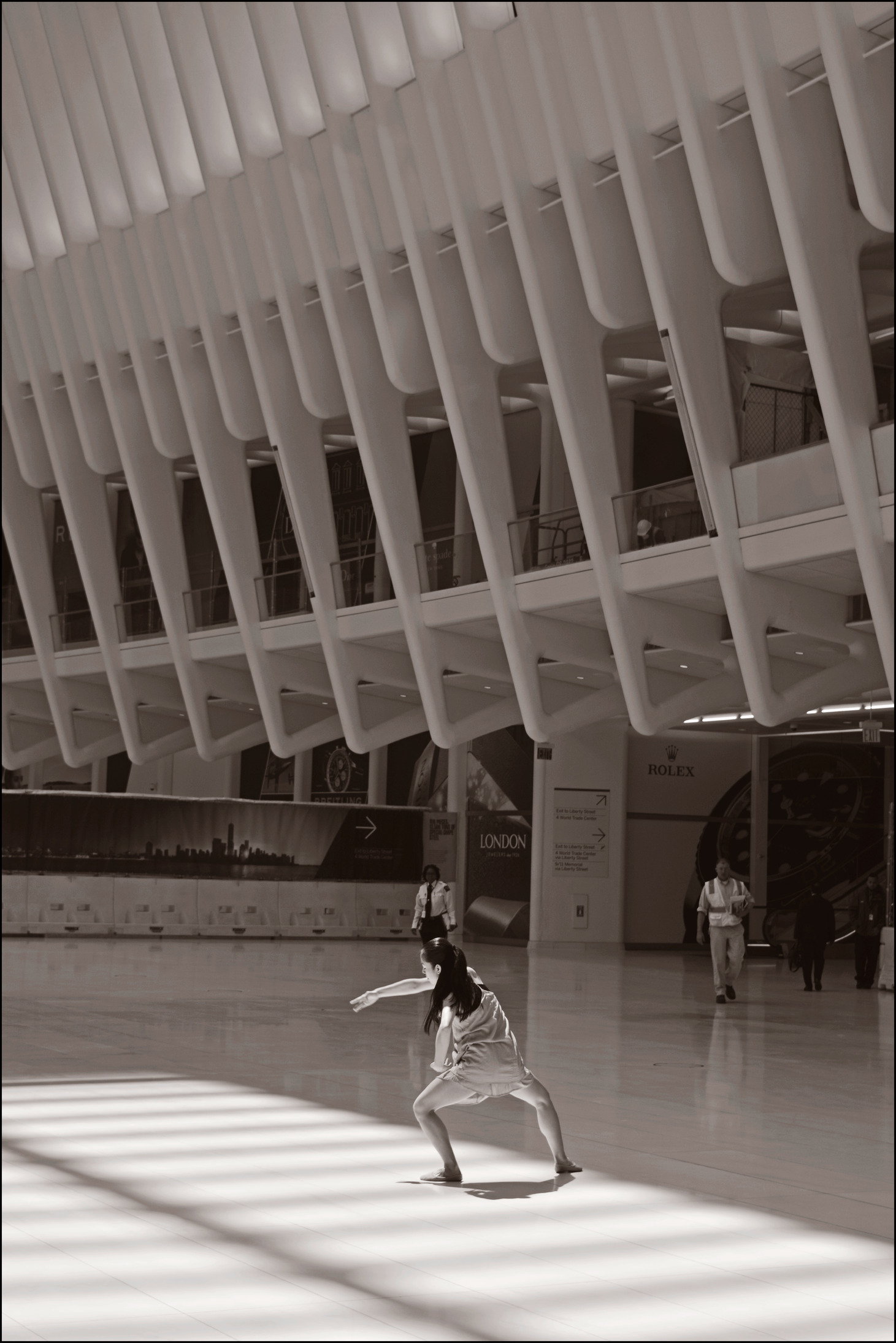

All this healing has come at immense cost: $3.8 billion for One World Trade Center; $700 million for the memorial and museum, with another $60 million a year in operating expenses; $4 billion for the world’s most expensive subway station, known as the “Flying Bird” and the “Stegosaurus.” The acerbic New York Post critic Steve Cuozzo, who took a special loathing to the station’s architect, Santiago Calatrava, dubbed his design the “Calatravasaurus.” I visited that, too, while it was under construction, and it was like standing in the center of a ruined arena or prehistoric observatory. Immense pieces of molded steel sat on plinths, like the bones of some giant fossilized beast. Above, curving steel fingers reached toward each other. The space between them framed a worm’s-eye view of the surrounding skyscrapers, which seemed to converge toward a point in the sky. Calatrava’s aesthetic emerged from the ruins of the ancient world—all those bleached, perfectly proportioned skeletons gleaming in the sun. That kinship was most obvious at this stage, before the openings had been glassed in, the two sides of the roof met, and the whole structure acquired its final pristine gloss—before, in other words, the structure got un-ruined.

In early 2004, Calatrava stood beneath the palm trees of the World Financial Center’s Winter Garden and drew a quick sketch of a child releasing a dove. That was the showman’s prelude to unveiling his design for the World Trade Center Transportation Hub,*6 a great white bird that charmed a roomful of skeptics. Finally, after all the earthbound squabbles and depressing compromises, here was an expression of upwelling joy. Calatrava had recently joined the rarefied ranks of celebrity architects. Then in his early fifties, he was still young in a profession with a notoriously lengthy dues-paying stage, but he had a clutch of flamboyantly energetic projects under his belt. His white-steel bridges flung themselves across rivers and ravines like ballerinas in mid-leap, a concert hall in the Canary Islands tossed back its sweeping coiffure, and his lakeside addition to the Milwaukee Art Museum evoked both ship and whale diving into the spume.

He promised a phantasmagoric piece of urban theater. Commuters would emerge from beneath the Hudson River into an architectural daydream. In Calatrava’s design, sunlight filtered through layers of glass and burrowed down to the platforms below ground. A few steps up the escalator, and the city’s towers appeared through a curving transparent shed. A public plaza wrapped itself around the station and beneath the building’s soaring canopies, merging the lobby with the street. Here, at the edge of the memorial’s sober acres, would be a place for crowds to mingle: a full block of exuberant urban chaos capped by a stunning, luminescent structure. The station he spoke of preened, arced, and spread its wings; the spiky extensions were designed to flap a little when the roof parted along its spine, opening the atrium to the sky.

It’s difficult to remember at this remove how desperately those of us who watched Calatrava perform his magic trick with a Sharpie wanted him to uplift the process of reconstruction. We craved something better than a plain old New York–style real estate deal, and that’s what he promised.

A lot has changed since then: Towers have risen, trauma has been enshrined, and the scar tissue between the site and the city has slowly begun to heal. And Calatrava is suddenly, stunningly out of fashion, amid reports of leaky roofs and wobbly bridges and budgets gone kablooey. He has turned from a humanist hero into the emperor of self-indulgence, pilloried for invoking facile metaphors from nature, for randomly defying convention, for pushing against the limits of buildability, for bequeathing intolerable maintenance burdens, for indulging in visual razzmatazz instead of just getting the job done, and, mostly, for erecting budget-guzzling luxuries. A man of grandiloquent visions and erudite charm, he managed to cajole unsuspecting bureaucrats on both sides of the Atlantic into buying more than they could pay for. He sometimes sacrificed practicality on the altar of amazement.

It didn’t help that, after terrorist attacks on railway targets in London and Madrid, he had to thicken the hide on his glass cocoon. Along the way, the cost leaped from the huge to the inconceivable. The word “obscene” was tossed around. Those who applauded him in 2004 later came to feel a little foolish, as if Calatrava had performed a conjuring trick on them and picked their pockets at the same time. But he did neither. He had an idea, and everyone loved it. It still seems like a good idea, a boondoggle perhaps, and an overpriced architectural gadget, but still a thing of awe and wonder.

If those of us who felt the exhilaration of that day understood the financial implications better than the Port Authority had, would we have swallowed hard and rained brimstone down on the design? Maybe, but hardly anyone did. Like most critics, I waxed rapturous: Calatrava, I wrote, had conceived “an optimistic emblem of flight as an answer to airborne disaster.” I still feel that way. It seems miraculous that Calatrava’s daydream should now finally exist, altered yet recognizable. Its frame is a little less lithe, its skin a little less smooth, its concept more mature. What remains is an extravagantly idealistic creation unlike any in New York. It challenges the city’s public architecture to rise above habitual cut corners and rectilinear repetition. The cost of beauty is often high.

The station disrupts the World Trade Center’s relentlessly Cartesian arrangement. It roosts at the foot of towers, steel-veined wings almost brushing an adjacent façade. Sitting aslant the grid of streets, it pivots toward the morning sun. The Transportation Hub is a buried, tentacled affair, stretching toward both rivers and linking the PATH with eleven subway lines, but the part that pokes above ground is the Oculus, the building’s great white eye. Observed from a high floor of a neighboring address, it seems to squint—especially when the retractable skylight blinks—and the wings metamorphose into lashes. Does any work of architecture in New York turn such an expressive face to the clouds?

Calatrava originally designed the wings to dip, a ludicrously literal flourish that was wisely scrapped. What remains of that urge is the illusion of motion contained in every view. Outside, the eye is drawn up and out in a parabolic swoop. Along the exterior flank, the parallel columns appear to accelerate like bicycle spokes. In the PATH Hall that extends beneath the memorial plaza, steel lines flow horizontally, undulating across the ceiling to make an underground chamber feel like a dive beneath the waves.

Dancer in the Oculus

The Oculus*7 merges a flock of organic allusions, but its most astute homage to nature lies in the way it makes visible the forces of gravity and shear. Calatrava began with a basic engineering tool, the bending-moment diagram, which shows the stresses on a cantilevered beam. Those calculations gave him the shape of each rib: an enormous boomerang that he could balance on one tip with the other tilted toward the sky. He lined up all these freestanding sculptures and attached them at the elbows, creating a pair of immense arches along the spine. If the whole massive ensemble seems held together by nothing at all, it’s because the Oculus is effectively a pair of separate clamshell-like structures, lightly joined at either end. You could knock one half down and the other would barely budge.

The large hall competes with Grand Central Terminal in its vaulted drama, but if you stand in the center and look up, the effect is more Pantheon-like: The eye finds a feather-shaped length of air instead of a central arch. The site’s master planner, Daniel Libeskind, had imagined a “Wedge of Light,” a frame for the rays that fall across the site at 10:28 A.M. every September 11—the moment when the second tower fell. Calatrava, honoring that idea, has the sun slice through the open skylight. And the rest of the year, when the vault isn’t serving that particular Stonehengian function, it still allows a generous portion of sunshine to cascade down into the hall.

Cost is an objective fact; value isn’t. Whether you consider this station splendid overkill, an ugly boondoggle, or a lasting work of genius depends on a host of intangibles. Granted, you can move one hundred thousand commuters in and out of New Jersey every day a good deal more modestly and cheaply. (Penn Station manages five or six times that number of passengers.) But the Hub serves an area that is both the oldest and the newest part of town and keeps changing in ways that planners have never been able to predict. There’s a good chance that more commuters will arrive as new offices materialize, old ones become apartments, and the neighborhood acquires residents who will flow through the Oculus in search of dinner, a shirt, or a meeting spot. I doubt it will ever feel empty. In the end, we are left with a structure that must endure a century or more. Calatrava’s skeletal dove joins the tiny circle of New York’s great indoor public spaces, serving not just the city that built it but also the city it will help build.

Lower Manhattan seen from the S.S. Coamo, 1941