Midwinter in Bryant Park:*1 With year’s end a few weeks away, I meander among the stalls that sell hot chocolate, fried dough, and alpaca mittens. The scents of sugar and cinnamon fill the cold air, and the stylish fuchsia hand warmers I have just bought from one of the booths are turning my coat pockets into little heated pouches. In the skating rink at the center of the block, gaggles of office workers and tourists wobble across the ice, parting occasionally to let an insouciant show-off glide by with one leg outstretched. Next to the rink, diners crowd into Celsius, the two-story temporary restaurant bolted together each fall like a giant erector set and taken down again a few months later. Every winter, the park becomes a festive village of miniature huts and adorable alleyways encircled by towers and the gracious bulk of the New York Public Library.

Forty-second Street runs along the park’s northern flank, and in the midst of all this seasonal sparkle I think about the street’s reputation as an artery of sordid drear. From the Civil War to the 1990s, from the slaughterhouses along the East River to the rail yards by the Hudson, this stretch of pavement, pounded by hookers, con men, addicts, and pickpockets, knitted together the most distasteful parts of urban life.

But for just as long this has also been New York’s most idealistic street. Here fine instincts and modern technology fused into a boulevard of high-minded civic aspiration. Manhattan’s most visionary places and institutions line up along Forty-second Street: the United Nations, Tudor City, the Daily News Building, the Chrysler Building, Grand Central Terminal, the New York Public Library, Times Square, the New York Times Building. Even its roster of vanished landmarks is a testament to loftiness.

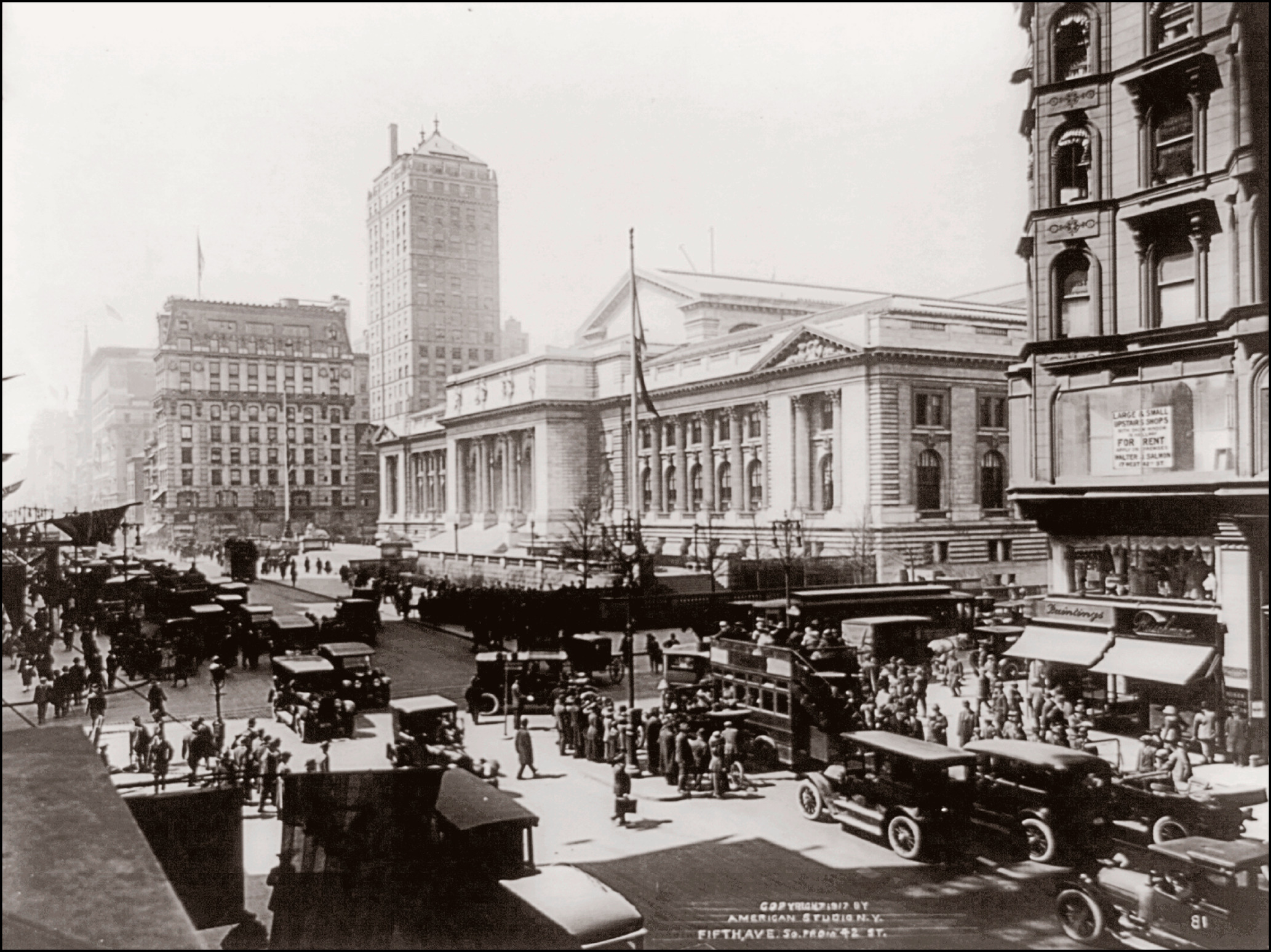

Fifth Avenue looking north toward Forty-second Street, 1912

My thoughts wind back through the decades. The scene before me dissolves: Winter turns to summer, puffy parkas and cold-stiffened jeans metamorphose into coarse wool suits and calico cottons dampened by summer sweat. The traffic sounds change, too, from a motorized roar to the clatter of hooves and iron-rimmed wagon wheels on hard-packed dirt. Suddenly I am standing not in a geometrically laid-out park beneath naked, trembling trees but in a rough clearing, looking up not at the public library but at an even more formidable monument looming in the predawn haze. This is the Croton Distributing Reservoir, a perfectly square, battlemented perimeter guarding a four-acre enclosure.

Sunrise, July 4, 1842: A handful of early risers—not including the mayor, who’s running late—have gathered to witness a miracle of engineering. This island in a tidal estuary, laced with murky canals and surrounded by brackish currents, has been in dire need of clean, drinkable water. Here it comes, piped in from the Croton River, muddy at first, then clear and sweet. It rushes through forty-five miles of tunnels that have been blasted and dug and lined with brick, crosses the Harlem River atop High Bridge and into the vast Eighty-sixth Street reservoir (in what will later become Central Park), through more massive tubes, and flows into the great cistern at Murray Hill. From here it will branch into narrower pipes and plash from public fountains and newfangled fixtures in private homes. Croton Reservoir is really just a holding tank, but it’s the most visible juncture in an immense new aqua-management system that will soon tip New York into a global metropolis. Over the rest of the day, twenty-five thousand people will converge on the reservoir to watch it fill and to line up for a free drink of ice water.

The Croton Reservoir just before demolition, 1900

In the twenty-first century we take infrastructure for granted, except on those occasions when a gas main blows or a bridge crumbles. We don’t go on outings to admire a highway interchange or visit an airport for the view. We’ve lost our ability to marvel at great works. But in 1842 New Yorkers still had some awe to spare for a plain stone wall plunked down in the rocky, uneven terrain at the edge of settled Manhattan. This guarantor of a city’s most basic necessity became an idler’s destination, an elevated loop where people strolled and enjoyed the panoramic view.

The Croton Reservoir took years of planning and the then-colossal sum of $13 million to complete, and there was plenty of grumbling at the extravagance and delays. After all, New Yorkers were not accustomed to receiving much in the way of municipal services. The city still lacked a police force, garbage collection, and electricity, and it had only the sketchiest form of public transit. Not everyone saw the need for those embellishments. But in July 1832 cholera attacked, killing thousands and inciting many more to flee. So many people left that by August, New York was eerily quiet and the air disturbingly free of smoke from factory furnaces. Three years later, fire decimated the mercantile core around Wall Street, destroying seven hundred buildings, including the supposedly indestructible Merchants’ Exchange. On that frigid night in December 1835, firefighters could only stand helplessly by, water frozen in their pumps, until they were finally able to stop the destruction by dynamiting unburned buildings and creating a firewall of rubble. Suddenly an aqueduct looked like an instrument of survival.

In 1842, water was a promise and a balm, irrigating the city’s ambitions and nourishing its future growth. The aqueduct was built for the ages: Its architecture invoked ancient Egypt, and its scale seemed eternal in a city destined for rapid change. Walt Whitman joined the throngs who clomped up the stone stairs for the view, and it roused in him enthusiastic fantasies of posterity and grandeur. He imagined strollers in the future looking out on a city that had expanded to enfold the reservoir, a megalopolis that had spread even into the Forties and beyond:

The walks on the battlements of the Croton Reservoir, a hundred years hence! Then these immense stretches of vacant ground below will be covered with houses; the paved streets will clatter with innumerable carts and resound to deafening cries; and the promenaders here will look down upon them, perhaps, and away “up town,” towards the quieter and more fashionable quarters, and see great changes—but off to the rivers and shores their eyes will go oftenest, and see not much difference from what we see now. Then New York will be more populous than London or Paris, and, it is to be hoped, as great a city as either of them—great in treasures of art and science, I mean, and in educational and charitable establishments….Ages after ages, these Croton works will last, for they are more substantial than the old Roman aqueducts…

As it happened, Whitman’s “ages after ages” would last only sixty years, by which time the irrigated city had outstripped even his grandiose projections, and a far more extensive web of pipes made the reservoir obsolete. That’s the thing about New York: Today’s unimaginable ambition becomes tomorrow’s quaint relic. New York in the 1840s was a swaggering adolescent, a bit insecure but ready for great things. And Forty-second Street has always been where New Yorkers come to think big and to solve seemingly intractable problems by force of imagination.

This thick belt of a street is where the press (the Daily News, the Herald Tribune, the Times, and The New Yorker) have continuously tested the limits of the First Amendment, where pedestrians reclaimed civic space from cars and dereliction (in Times Square), where doctors tended to wounded veterans (the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled, which once existed between First and Second Avenues). Charity workers (at the Ford Foundation) tried to stanch the world’s worst ills, and a global financial institution (Bank of America) erected what was then the world’s greenest skyscraper. On Forty-second Street, even the destitute can enter one of the world’s great research libraries, sit in its aristocratic reading room, and dive into virtually any published book (or simply nap in peace), without paying a dime. And half a dozen blocks east of the public library, diplomats from all over the world convene to hammer out intractable conflicts, not with weaponry but by sitting around a conference table and talking. When you think about it, Forty-second Street isn’t just the epicenter of spectacle but also a boulevard of noble ambitions.

That’s not an especially sexy reputation for a major thoroughfare, especially one with such a famously skanky past. But what makes this the quintessential New York street is that tinsel and marble coexist so naturally here. If you see an unkempt man shuffling along the sidewalk in a ragged jacket, the remains of breakfast still clinging to his beard, you might not be able to tell if he’s a scholar heading for his assigned carrel in the library, a hobbyist seeking out the last remaining porn shops along Eighth Avenue, a Pulitzer Prize–winning Timesman, or Mandy Patinkin on his way to a rehearsal for a Broadway show.

But let’s imagine that he’s Whitman again, having descended from the ramparts to confront a more dramatic and detailed version of the future. It’s July of 1853 now, and in the field next to the reservoir rises the Crystal Palace, all airy cast-iron lacework, topped with a great glass dome—the largest building America has ever seen. The reason for its existence is the “Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations,” and, although it has taken less than nine months of construction and portends a future of technological marvels, its builders are grateful to have gotten the thing up at all. The press is obsessed with its size, reverently enumerating every possible dimension. At a time when many Americans still sew their own clothes, visitors to the industrial fair wander through a cathedral of industry. According to the official catalog of the exhibition, experts demonstrate strange-smelling chemicals, woods destined for furniture, “specimens of New-Orleans long moss for upholstery purposes,” immense, clanking steam engines, “an improved machine for breaking and dressing flax,” maps, window dressings, pistols, scythes, and “philosophical instruments.” The building shows off the new art of photography, and it also shows up well in photographs: A plethora of daguerreotypes at the fair is turning New York into the medium’s effective capital. Several times a day during the Palace’s second summer, Elisha Otis slices the cable on his demonstration elevator, proving over and over that his patented safety catch will keep passengers from plummeting to the ground.

Whitman doesn’t just visit the exposition—he haunts it. He returns again and again, as if trying to absorb its minutiae and revelations. The fair’s encyclopedic hopefulness permeates his verse. Nearly two decades later, he will write “Song of the Exposition,” which still quivers with the freshness of that first encounter with the industrial art:

Around a Palace,

Loftier, fairer, ampler than any yet,

Earth’s modern Wonder, History’s Seven outstripping,

High rising tier on tier, with glass and iron façades.

The Crystal Palace

The fact that the Crystal Palace attracts so much attention makes some observers nervous that New York might embarrass itself in front of a skeptical world. Scientific American, which printed a lavish and moody rendering of the building on its cover before construction had even begun, takes umbrage at the condescending jibes being lobbed across the Atlantic. New York aches to be taken seriously, but the truth is that it can’t quite keep up with London or Paris. Its grandeur is punier, its monuments less monumental, its extravaganzas less extravagant. The Crystal Palace is, reporters reluctantly admit, about one-eighth the size of London’s.

And, in a remark that will soon become a refrain, the Times frets that crowds are being lured to a dicey part of town: “We warn the authorities against permitting this indiscriminate growth of taverns around the Crystal Palace. Half its attraction, half its beauty will vanish, if those poisonous fungi are allowed to grow undisturbed around its base.”

If, more than a century and a half later, I linger on a building that collapsed in a quick and violent fire after just three years, it’s because for me it represents the tension between materialistic ambition and the street’s history of shabbiness. The industrial exposition heralded modernity’s promise: a good life of speedy travel, well-tended health, well-lit leisure, and comfortable work. A few decades later, that promise devolved into the kind of urban ghastliness that sent millions skedaddling to the suburbs. Yet now, as I sit on one of the metal chairs scattered on the gravel walkways of Bryant Park, I’m amazed anew at how many thousands of people I could count in five minutes of sitting and how many different purposes propel them past this corner. Out on the sidewalks beyond the park’s balustrades, New Yorkers move with a determined stride, bulling past slow-moving families of tourists and high-end shoppers clutching their branded cargo. The Bank of America Tower, a cream-white glass behemoth designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox, disgorges lunchers. Young men in suits steer blue Citi Bikes around cabs and plumbers’ vans and double-decker tour buses. A woman in sunglasses talking into her headset steps blithely off the curb against the light and lopes through the inching traffic without a pause in her conversation. Two blocks west, the crowd in Times Square often seems to consist of unadulterated tourists; two blocks east, the UN’s international army of diplomats fans out across several blocks. But right here, if you scooped up a shovelful of passersby at any given moment, you’d find that you’d collected specimens from most of the world’s nations and the full economic spectrum from homeless person to plutocrat, with every gradation in between. I think of Harry Warren and Al Dubin’s lyrics for the film musical 42nd Street: “Where the underworld can meet the elite…Naughty, gaudy, bawdy, sporty / Forty-second Street.”

It’s not happenstance that in 1952 Ralph Ellison chose the street just outside Bryant Park as the setting for a viciously climactic moment in Invisible Man. Today, that scene reads like the overture to the grim roll call of unarmed black men killed by cops over minor infractions: Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Philando Castile, and so many others. Ellison’s narrator comes across the once-proud Brother Tod Clifton selling Black Sambo dolls on the sidewalk, making them shimmy in a grotesque minstrel dance at the end of a thread. When a policeman bears down on him for lacking a vendor’s permit, Clifton lashes out, effectively committing what we now call “suicide by cop.” As the officer’s pistol fires, Ellison registers the shock of a primal act on a crowded street, where tragedy and minutiae jangle in an urban freeze-frame:

He fell forward on his knees, like a man saying his prayers just as a heavy-set man in a hat with a turned-down brim stepped from around the newsstand and yelled a protest. I couldn’t move. The sun seemed to scream an inch above my head. Someone shouted. A few men were starting into the street.

Or try watching Midnight Cowboy, a 1969 ode to sleaze. Joe Buck, a good-looking, buckskin-clad dishwasher from Texas (played by Jon Voight) arrives in the big city, eager to sell his body for, well, a buck. He counts out his change to pay for a room at the Hotel Claridge, which once upon a time had been equipped with red runners and gilt-trimmed settees. But when Buck arrives it’s one step up from a flophouse, with a begrimed view onto Times Square, the universal magnet for hustlers. The movie portrays Manhattan as a ruthless isle: No matter how sordid your dreams, newcomer, you are still aiming too high.

That fiction was not a stretch in the seventies, when the merchants who frequented the leafy geometric plain of Bryant Park sold forms of joy more treacherous than today’s hand warmers and hot chocolate. Happiness was a heated spoon with a dose of heroin bubbling away in it, and the paths were carpeted with needles. “It’s a dangerous park,” a groundskeeper told the Times in 1976. “There’s a crew in this park, all they do is walk around and mug people. It goes on all day.” A demoralized community board chairman suggested that the only way to disinfect the park of crime might be to close it completely. Forty-second Street from Sixth to Eighth Avenues—from Bryant Park to the Port Authority—was a frightening caricature of urban threat. “Times Square, which for generations had been understood to exemplify the freedom and the energy and the heedless pleasure-seeking of New York, now came to be seen as the emblem of a city deranged by those very attributes,” wrote James Traub in his astute urban portrait of the area, The Devil’s Playground.

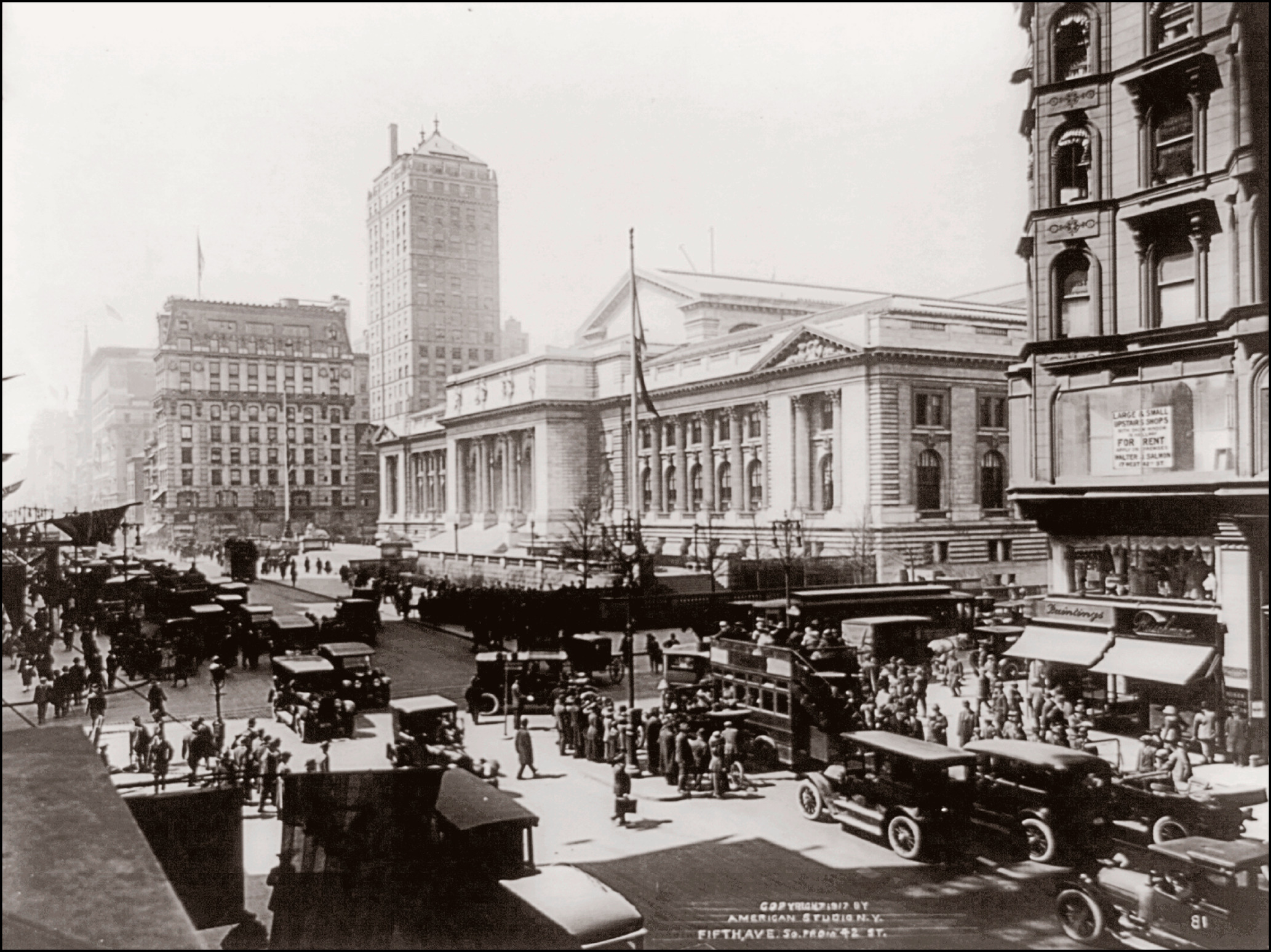

Fifth Avenue at Forty-second Street, looking south toward the New York Public Library, 1917

Even at its grimmest, this area abutted some of the city’s most high-minded civic institutions—the New York Public Library,*2 for example, which sits right where the Croton Reservoir did. From where I sit on the Bryant Park side, the library seems forbidding, pinstriped by great vertical piers and narrow windows that look as if they were designed to repel a siege. Go around to the Fifth Avenue side and it is formidable in a different way, an august institution raised on its own temple mount. Actually, it’s a genuinely inviting place, designed to welcome the masses.

Since the day the library opened in 1911, anyone, from the barely literate to the Nobel laureate, could pass between the friendly lions named Patience and Fortitude and climb the imperial-scaled stairs to the third-floor Rose Main Reading Room. With its profusion of sunlight and carved timber, and its great oak tables burnished by millions of elbows, the chamber expresses the democratization of earthly awe: Even people who live in joyless garrets have a right to grandeur.

Frank Larson, Lady and the Lion, 1955

At a time when electricity was still relatively novel and far from universally available, the architects John Carrère and Thomas Hastings offered readers a vast menu of illumination. There’s the daylight that blazes in through one wall of great arched windows and passes to the other in the course of the day; the illusory radiance that suffuses the painted frescoes on the ceiling; the theatrical glow from two rows of hanging chandeliers; and the incandescent cone formed by the shaded desk lamp at each chair. Ironically, technology has made all that brilliance a hindrance instead of a help to reading. On sunny days, you can see researchers and scholars squinting at their laptops, shading the screen with one hand.

In that image you can see the paradox of the great library in the digital age. While information increasingly lives in the ether, the New York Public Library’s headquarters is an intensely physical place. This iron-and-stone storehouse was built to enshrine knowledge in ink-on-paper form. Its massiveness guaranteed that no word it contained would ever be lost and there would always be room for more. But temples grow brittle. In 2014, one of the rosettes on the reading room ceiling broke off, failing to kill any patrons only because it happened in the middle of the night. The room closed for renovations for two years.

That’s not the only structural problem. Eventually, the library found that its overcrowded storage system was threatening its contents. The public isn’t allowed into the stacks, but a few years ago I had the chance to explore the claustrophobic and endless honeycomb where four million volumes moldered away in a warm, damp fug. This is both the library’s heart and its skeleton. Thickets of iron columns and seven levels of tightly gridded shelves, held in place by ornamental cast-iron plates, support the upper floors. For a century, the reading room rested on piles of books. Recently, though, the volumes have been moved for their safety, most of them to a newly renovated, climate-controlled vault deep beneath Bryant Park. The old retrieval system endures, albeit in updated form: Whenever a call number is dropped (electronically, now) into the building’s bowels, library staffers—aptly called pages—unearth the requested titles and place them on a miniature train that hauls them up to the surface like hunks of coal from a mine. Meanwhile, the original stacks sit empty, patiently holding the architecture together and waiting for a fresh purpose.

The other great Beaux Arts monument of Forty-second Street did for travel what the library did for reading: surround the experience with splendor. A few years ago, I asked half a dozen renowned architects and urbanism experts to name their favorite building in New York. I expected an argument—perhaps an Art Deco skyscraper versus the Seagram Building. Instead, I got virtual unanimity: Grand Central Terminal.*3 I agree.

Every time I duck in from Forty-second Street, I’m struck again by how the building makes me wait a couple of beats for its great architectural climax. A ramp guides me toward the great waiting room, a place fit for a coronation or a conclave of gods but one that makes a puny commuter feel ennobled, too. It is a place I come with pleasure even when I have nowhere special to go.

Grand Central opened a century ago as a triumphant fusion of profit and public-spiritedness. Designed by the firms of Reed & Stern and Warren & Wetmore, it was the emblem of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s New York Central Railroad and the endpoint of a transportation system that webbed the entire continent. (Today, it’s where a handful of commuter lines converge; oh, how the mighty railroads have fallen.) The building’s history begins with a horrific accident. In the morning rush hour of January 8, 1902, two trains collided just outside the old depot on the site, filling the tunnel with boiling spray and coal smoke. Fifteen people were killed. The New York Central Railroad decided to switch to electric trains, which didn’t pump fumes into the air and so could run beneath the streets and enter the station from below. The company’s chief engineer, William J. Wilgus, realized that it could pay for an underground station by selling the right to build in the air. Thanks to that insight, Grand Central Terminal became one of the world’s most high-tech facilities, dedicated to the era’s great mission: speeding people wherever they wanted to go. It also incubated a colossal real estate project, creating the concept of air rights, which has been a staple of New York development ever since. Burying the open tracks created Park Avenue and a grove of new towers.

In Europe, most train stations of that era consist of a huge anteroom facing toward the city and platforms leading away from it. Arriving passengers typically haul their luggage out of the station and onto a vast but confusing outdoor plaza, where they have to hunt for trolleys, buses, cabs, and information, and where they are easy marks for con artists waiting to rip them off. Grand Central stacks its transportation functions vertically: trains below, linked to the subway, with city streets on all four sides and an elevated roadway wrapping around the outside. People arrive on every level and from all directions, and they can rush in one side and out the other, converge on the focal point of the waiting-room clock, pause for a meal on the mezzanine, or pick up (extremely high-priced) groceries on the way to the train.

In the rationalistic spirit of the age, the building was engineered down to the minutest detail, merging efficiency with beauty. Hallelujah shafts of sunlight angle through vast double windows and glass-floored walkways, heating the interior and minimizing the need for electric lighting. Early visitors rhapsodized over the ramps from street to tunnel. “The idea,” reported the Times, “was borrowed from the sloping roads that led the way for the chariots into the old Roman camps of Julius Caesar’s army.” To determine their precise angle, the architects made mock-ups and then recruited testers: “fat men and thin men, women with long skirts, women with their arms full of bundles.” The result is a complex of gentle slopes through which people move in a counterpoint of varying tempos. Thanks to that attention to detail, Grand Central was—and remains—one of the modern world’s most exquisitely complex and welcoming public palaces.

Is there any human activity that architecture can’t elevate? The Chrysler Building,*4 an auto company’s monument to itself that functioned as an urban-scale corporate logo, stamped the skyline with the glamour of driving. The original plan for the Daily News Building called for a low-rise home for a rumbling printing press that might rattle nerves in a newsroom above but had no sleeping neighbors to disturb.

Architect Raymond Hood reimagined it as a skyscraping tribute to the business of asking rude questions of powerful people. I spent a dozen years working at Newsday, a suburban tabloid whose headquarters was a sprawling two-story box encircled by parking lots and roadways that never saw a pedestrian. I felt deprived of architecture and yearned to work someplace like the News Building, which started construction in 1929 and opened in 1931 in a burst of delusional confidence, as if the Depression were just another journalistic opportunity.

The man who paid for it was Captain Joseph Medill Patterson, the left-leaning scion of the McCormick family, which owned the Chicago Tribune. (Patterson’s daughter, Alicia, would later found Newsday, the paper I worked for.) Every great venture has its creation story, and the News’s is especially redolent: During World War I, Colonel Robert McCormick and his cousin, Captain Patterson, sat on a manure pile in the French village of Mareuil-en-Dôle and indulged in a drunken fantasy of life back home. Patterson, a populist idealist, had spent time in England on his way to the front and fallen in love with the Daily Mirror, a cockney-flavored tabloid that kept Londoners supplied with salacious gossip, provocative pictures, and short, punchy stories. He decided to create, with McCormick’s help and Tribune money, a similar publication for New York. The first years were brutal for the business, but by 1926 the News had won over the lunch-pail classes, and its circulation rose from ten thousand to well over a million, making it the largest daily in the country. After a few more years of success, Patterson knew where to place a new printing press—on Forty-second Street, close enough to the Times that he could beat the competition to the newsstand every day. He also knew who should design the building: Raymond Hood, who had won the famous 1922 competition to build the Tribune Tower in Chicago. If Hood was good enough for McCormick, why should Patterson use anybody else?

Patterson wanted a printing plant with a newsroom on top; Hood charmed him into building a thirty-six-story skyscraper. Negotiations were tense, until the moment when Patterson shrugged and surrendered: “Listen, Ray, if you want to build your goddamn tower, then do it,” he said.

Lobby of the Daily News Building, 1930

Hood insisted that his design was the product of calculation, not inspiration:

When I say that in designing the News Building the first and almost dominant consideration was utility, I realize I am laying myself open to a variety of remarks and reflections from my fellow architects, such as: “It looks it!,” “What of it!” and so on. However that is my story…In passing, I might remark that I do not feel that The News Building is worse looking than some other buildings, where plans, sections, exteriors and mass have been made to jump through hoops, turn somersaults, roll over, sit up and beg—all in the attempt to arrive at the goal of architectural composition and beauty.

Hood, like Patterson, was an avowedly practical man for whom money was—in theory, anyway—an infallible guide. Patterson demanded that articles be short and photos shocking, because that was what would sell papers; Hood kept ornaments spare and proportions precise, because that would please the client’s accountant. In his mind, and in his rhetoric, the News Building*5 was the manifestation of virtuous slide-rule thinking, which held that the most efficient way to design a building was inherently the most harmonious as well. If that seems like an odd credo for an architect who had beribboned the Tribune Tower in Gothic frippery, it was also the founding doctrine of modernism, which later architects boiled down to an austere language of glass and steel.

High-end New York real estate has always been replete with symbols, metaphors, and irrational desires. Letting arithmetic design a tower is like using a protractor to plan out sex: It can probably be done, but it’s not likely to yield the best results. Despite his declared pragmatism, Hood produced an artistic creation, a jazzy concoction of syncopated setbacks and white brick stripes shooting toward the sky. In a city of flat façades, this was a sculpture to be appreciated from all sides. Hood claimed that he simply stopped the building when he ran out of floors, rather than capping it with some fancy crown, but in truth the corrugated shell extends well past the roof, hiding the mechanical equipment and defining the top with a straight, sharp horizontal line. Simplicity is not usually simple to achieve.

Like all good architects, Hood knew how to deploy his budget for maximum effect, concentrating all the sumptuousness where people could see it. The relief above the main entrance resonates with Patterson’s fondness for brief texts and telling illustrations. It teems with New Yorkers of all kinds—flappers, construction workers, financiers, a young girl telling off an overenthusiastic dog—and an inscription abridges Lincoln’s aphorism “God must love the common man. He made so many of them.” (The News version includes only the second sentence.)

The shiny black-and-brass lobby is even stagier, with its quartet of clocks set to various time zones and its giant globe, symbolizing the paper’s worldwide reach. As an example of journalism’s public face, this was the antecedent of the maps and screens and headline crawls in today’s TV newsrooms—a statement that going out into the field and coming back with a story is serious business, best left to the pros. The News eventually abandoned the building (and many of its global ambitions), but so completely did Hood’s design capture the urban drama of journalism that his tower had a starring role in the 1978 film version of Superman, playing the headquarters of the Daily Planet.

I’ve already observed the various ways in which, in just a few blocks, architects and dreamers turned necessity into pleasure, often by merging public-spiritedness with unapologetic self-interest. Water, knowledge, manufacture, transportation, business, news—each of these aspects of culture produced a building that was better than it really needed to be, feeding a city’s aspirations to greatness. What was missing was shelter.*6 Whitman, gazing down on the district from the ramparts of the Croton Reservoir in the 1840s, imagined an orderly grid of private houses popping up as the city expanded, but the reality was more chaotic. To the east, squatters erected shantytowns of mud and planks. Before the Civil War, as workers laid the rigid street grid over rough terrain, they left houses clinging to mini-escarpments between the freshly graded roads. For a time, the nineteenth century’s menu of modern improvements—streets, industry, and public transit—ruined the area. Affluent New York families had their country estates overlooking the rushing East River, but industry swallowed them up. Starting in 1878, the Third Avenue El clattered above the street all the way from the Bronx to South Ferry, dividing the genteel neighborhoods along Fifth and Madison Avenues from the stench and misery farther east. In the 1880s, Paddy Corcoran and his “Rag Gang” dominated the rocky bluffs of Prospect Hill, above First Avenue. A 1988 Landmarks Preservation Commission report, usually a dry research document, indulged in a vivid description of the zone’s afflictions: “Bracketed to the west by the noisy Elevated Railroad and to the east by noxious abattoirs, meat-packing houses, gas works, and a glue factory, the area…had, by 1900, become a slum inhabited by ethnically diverse immigrants.”

Enter Fred F. French, a brawny Bronx kid who had dropped out of college and had a knack for getting fired from low-paying jobs. French treated his own poverty as an excellent business opportunity. He enjoyed talking about the time he borrowed five hundred dollars from an acquaintance, blew ten dollars on a lavish meal, and then parlayed the rest into his first real estate deal: He bought his family’s cramped house. Eventually he became a bona fide mogul, and his mantra was that he’d rather make a small profit on a large business than a large profit on a small one. And the biggest real estate business of them all was Tudor City.

Climbing the stairs to get there is like shinnying up Jack’s beanstalk; I emerge into a serene and verdant world perched above the roar of traffic and the commercial jangle of the street. It aspires to the picturesque tranquility of an Elizabethan village, amplified to urban scale. Launched in 1925, Tudor City was the largest residential complex in the country. It was also a control freak’s fantasy, a hilltop enclave of eleven buildings with 2,800 apartments—practically a manufactured town. It boasted its own streets, hotel, a slightly cramped but fully operational eighteen-hole golf course, and two parks, each with a romantic gazebo. In building it, French placed the high-yield, high-risk bet that has enriched—or, often, impoverished—developers in every generation: He believed that middle-class people would choose to live in the city, rather than migrate out of town, so long as they could keep urban squalor and chaos at bay. He promised working stiffs an affordable bucolic refuge that didn’t require a long commute.

French fitted out his buildings with modern efficiencies (like refrigerators) and architectural flourishes evoking the days of monarchs in wide collars and rich brocades. Carved griffins, stained-glass windows, and ornate lanterns turned the oversize brick boxes into middle-class castles. The strategy worked. The development was stupendously successful, despite tiny apartments with almost no eastward-facing windows. Enjoying a river view would have had a disconcerting downside: a vista of charnel houses and the stench of blood and offal drifting in from neighbors like the Butcher’s Hide and Melting Association. (Today, the abattoirs, the el, and the slums are all gone.)

Samuel Gottscho, Tudor City, 1930–33

French’s gamble extended the sphere of respectability eastward, and other developers followed. Ten blocks to the north, River House replaced a cigar factory at the end of East Fifty-second Street, staking out a position for ultra-deluxe waterfront living within spitting distance of some of the city’s most troubled slums. (To read more about River House, see Interlude IV, “City of Apartments.”) In the 1940s, the developer William Zeckendorf quietly accumulated seventeen acres of shoreline between Forty-second and Forty-ninth Streets—right below Tudor City’s cliff-top position—and then noisily announced that he planned to build a gargantuan development there called X City. Zeckendorf had seen the future and it was his to build. With its chorus line of office and apartment towers, ranging from thirty to fifty-seven stories, its beams of light pointed at the heavens, and its domed opera house, X City was a megaproject that would make Tudor City look like a sand castle.

In New York, as in most places, the term “developer” carries a taint, precisely because of the land-eating, shadow-casting, sky-blocking grandiosity of projects like these. In the movies, real estate moguls are constantly paying off politicians, evicting the powerless, and despoiling pretty landscapes in their sinister drive to acquire, build, sell, and start all over again. One of the most comically nasty of all fictional developers is Lex Luthor in the 1978 Superman (the same version that showcased the News Building). Luthor, played by Gene Hackman, lives in a sumptuous lair two hundred feet below Park Avenue (in Metropolis, not Manhattan, but still…) and dreams of total world acquisition. “When I was six years old,” he declaims, “my father said to me…son, stocks may rise and fall. Utilities and transportation systems may collapse. People are no damn good. But they will always need land, and they will pay through the nose to get it.”

Real-life big-time developers lend themselves nicely to caricature. A certain amount of rapaciousness goes with the job. They do—they must—wheedle tax breaks out of City Hall, demand zoning tailored to their needs, schmooze with the powerful, and flick away those who are not. They are secretive and dynastic. The New York real estate world is a gilded bubble populated by a handful of multigenerational clans: the Dursts, the Zeckendorfs, the Roses, the Ratners (originally from Cleveland), the Rudins, the LeFraks, the Speyers—and, of course, the family currently headed by that most Luthoran of moguls, Donald Trump.

Yet despite all that, I have a deep reserve of admiration for the adventurers who built New York, block by visionary block. This city was a real estate venture from its earliest days, and developers created from scratch many of its most authentically charming quarters (Washington Square, Gramercy Square, Prospect Lefferts Gardens in Brooklyn, Forest Hills Gardens in Queens), as well as its most towering monuments. Rockefeller Center was named for the family that built it. It takes a lot of nerve to scrounge a billion dollars and erect a skyscraper in the hope that others will want to live and work there. The bets are huge, the market fickle, and the city is always threatening to fall apart. But, then, a New York developer is by definition an irrational optimist.

Zeckendorf never did build X City, which joined the pantheon of forgotten projects. Instead, his fellow tycoon and principal rival, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., bought him out in 1946—not so that he could add to his gajillions but because he was convinced that the right deal could save millions of lives. Rockefeller saw the X City site as the ideal home for the United Nations.*7

If you’re looking for world peace, this is where they make it: the UN Secretariat, a big glass brick standing upright on the edge of Manhattan. The UN occupies a cluster of structures, but the Secretariat, the hive of diplomacy’s worker bees, is the international body’s contribution to the New York skyline.

Among the United Nations’ first tasks—before the partition of Palestine or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—was to shop for real estate. A scouting party examined various other sites, including the suburbs of Philadelphia, the Presidio in San Francisco, Fairfield County, Connecticut, and the site of the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens. But it was eventually decided that only Manhattan embodied the UN’s ideal of vigorous optimism. Besides, if thousands of diplomats from all over the world were going to converge in one place, it had better be somewhere with excellent restaurants. Rockefeller, in a supreme gesture of noblesse oblige, offered to buy Zeckendorf’s reeking acres of riverfront for $8.5 million (roughly $103 million today—still a spectacular bargain) and donate it to the organization. Wallace Harrison, who was court architect to both developers—he had worked on Rockefeller Center, designed X City, and would later collaborate on Lincoln Center—helped broker the deal. With the clock counting down on the UN’s deadline to select a location, Harrison grabbed a detailed site map, crashed Zeckendorf’s birthday party at the Club Monte Carlo on Madison and East Fifty-fourth Street, and made his hurried pitch. The developer barked a quick yes, scribbled his promise to sell on Harrison’s map, and returned to his party.

Having secured the money, the job, and the land, Harrison handpicked an international troupe of modernist architects and took on the role of ringmaster. Many contributed, but two squabbling geniuses could agree on almost nothing. The Swiss-French guru Le Corbusier and his Brazilian counterpart Oscar Niemeyer fought over the shape, number, and orientation of the buildings, whether the glass curtain wall should include a sun-shading grid of stone, and—most ferociously—who got credit for what. Le Corbusier complained to his mother of the “apparent kidnapping of [his] UN project by USA gangster Harrison.” The cocktail of haste, diplomacy, vanity, and genius might have yielded an architectural hangover. Instead, it produced the first monument of postwar modernism.

United Nations General Assembly and Secretariat

One thing designers and clients could agree on was that a new world should adopt a new architecture. During World War II, various dictatorships had poisoned imperial neoclassicism and official sumptuousness. So the polyglot team agreed on an international language, composed of innocence, transparency, and logic. This cool aesthetic was not an easy sell when it banged against inherited notions of grandeur. The city’s building czar, Robert Moses, wanted to link Midtown to the rest of the world by a suitably majestic boulevard, so he ripped out the Forty-second Street trolley tracks, widened the roadbed and sidewalks, planted trees, and slung a new ornamental bridge between the two halves of Tudor City. Suddenly a city street became the UN’s driveway, suitable for limousines or chariots or whatever form of dignified transport the world’s diplomats would choose to adopt. Meanwhile, Vermont senator Warren Austin warned that if the U.S. Congress was going to front the money for the General Assembly, the building had better have a dome. Niemeyer responded, reluctantly, with a squashed, shallow hump that looked as though it had been half-buried in the roof. He dressed it in terne-coated copper, which had a subtle silvery sheen. Workers later tried (unsuccessfully) to seal the roof by spraying on a crud-brown rubberized coating, making the cupola seem even more grudging.

This majestic emblem of comity was also a monument to paper-shuffling. The Secretariat is a vast receptacle of diplomatic industry, and it projects a clear and simple message: Peace takes work. Many critics found the complex soulless and its creators deluded in the idea that World War III could be averted by orderly administration. “If the Secretariat Building will have anything to say as a symbol, it will be, I fear, that the managerial revolution has taken place and that bureaucracy rules the world,” wrote Lewis Mumford in The New Yorker.

I toured the UN complex exhaustively in 2010, by which time it had devolved into a decaying time machine. Rain seeped around ancient windows and leached asbestos from crumbling ducts. Cumbersome fire doors broke up the flowing hallways. The Secretariat Building lacked sprinklers and blast-proof windows. Traces of original detail spoke both to the building’s elegance and to its obsolescence. The lobby’s green marble walls sported the lovingly designed but now culturally unsuitable ashtrays. In the great public rooms, pairs of vinyl-covered chairs were yoked together by steel bowls that hadn’t seen a cigarette butt in years but still gave off the bitter whiff of burned tobacco. Architecture that once promised a more perfect world had now seen better days.

A $2.1 billion overhaul restored the original spare elegance. As I look at the Secretariat from across First Avenue, the blue-green glass curtain wall sparkles like a Nordic waterfall, and the white concrete walls at either end gleam like sugar cubes. Everywhere you gaze, the refreshed campus looks like a period movie, the kind in which vintage cars shine. The Security Council’s sixty-year-old chairs have been reupholstered in bright Naugahyde, water stains have been cleaned off limestone and marble panels, wall hangings have been revivified, and decades of nicotine have been scrubbed away from buffed terrazzo floors.

All the cosmetic improvements are icing on a high-risk rescue of a creaky modern landmark. When crews began removing the Secretariat’s exterior glass curtain wall, they found that it was barely hanging on. Windows were just a bad storm away from popping off. And the surprises kept coming. Once demolition got under way, workers discovered that some concrete floor slabs were held together with wire mesh rather than reinforced with iron bars. Engineers tested the concrete’s strength by building an enormous tank on one of the floors and filling it with water. After forty-eight hours, the slabs hadn’t budged—which is fortunate, because if they had sagged at all, it would have meant tearing down the whole structure and starting from scratch.

Michael Adlerstein, the assistant secretary-general in charge of the renovation, had to contend with far more terrifying possibilities, too. After a car bomb blasted through the UN offices in Nigeria in 2011, security experts demanded that the Conference Building, which is cantilevered over the FDR Drive, be fortified with extra steel. Meeting halls were moved away from the vulnerable sections, creating new lounges—and fresh opportunities for décor. (One such space, paid for by Qatar, looks like the lobby of a luxury hotel in Doha.) Then, in October 2012, Hurricane Sandy pounded through New York, knocking out the brand-new air-conditioning system and causing $150 million in damage. It might have been easier—and possibly cheaper—to demolish everything and build anew. However, for an organization where precedent and symbolism govern every handshake, the historical meaning of the UN’s architecture still resonates.

David Fixler, an architect at the Boston firm Einhorn Yaffee Prescott, led the UN renovation; he says that the best way to be faithful to advanced postwar architecture is to honor its principles and discard its physical components. In the General Assembly Building, chalky sunlight filters through a wall of translucent windows into an atrium lined by sinuous white balconies. The glass, etched with a now-defunct photographic process, had to be junked and replaced with a more or less faithful copy. “Modern architecture anticipates change and expresses progress,” Fixler says. “Very few buildings of the modern era were designed for the ages.”

But there is one postwar building that was built to last forever—or that at least looks eternal: the Ford Foundation.*8

In 1968, just when permanence and idealism seemed like chimeras, Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo provided the do-gooding Ford Foundation with a solid, deeply dreamy headquarters, just west of Tudor City. Like other mid-century office buildings, it is made mostly of glass. But with its sunset-colored granite piers and weathered steel beams, the Ford Foundation has an imposing look of perpetuity. The warm bulk of its stone is like a ghostly memory of the Croton Reservoir. The patina of rust on the great beams suggests not decay but antiquity. The foundation’s mission is to battle the full panoply of timeless injustices around the world, and its home base is a see-through fortress, braced for an endless war. The building’s materials, arranged with a collagist’s sensitivity, create a dance of delicacy and brawn, permanence and fragility, stolidity and romance.

The Ford Foundation did for the office building what Tudor City had done for the apartment complex: smuggle nature into its heart. Today, green design is often a color-coded metaphor, a checklist of energy-saving features that soften a building’s environmental blow. Roche, however, created a work of environmentally sensitive architecture before the term had much currency. The main staff entrance is on quiet Forty-third Street, but during business hours anyone can step out of the cacophony of Forty-second and into an indoor Eden. Walkways made of chocolate-brown glazed brick thread through an almost preposterously lush bower, where every leaf appears to have been polished by hand. This multi-story cloister, designed by the landscape architect Dan Kiley (and closed in 2016 for a two-year renovation), was meant to inculcate a sense of serene, almost monastic community in the foundation’s pencil-wielding professionals. “It will be possible in this building to look across the court and see your fellow man or sit on a bench and discuss the problems of Southeast Asia. There will be a total awareness of the foundation’s activities,” Roche predicted before construction had even begun, and he was right.

Ford Foundation atrium

Achieving that effect meant sacrificing some of the real estate developer’s vital essence: square footage. Ford gave up substantial floor area for the sake of trees, light, and air. That sacrifice made the building itself a magnanimous gesture, a gift of greenery to a city that has always been invited in to enjoy it; I stop in there virtually every time I walk past. Part Victorian greenhouse, part modernist Crystal Palace, part corporate plaza, the landscaped atrium was a powerfully original idea, even though it later became a cliché. What better place to end a tour of civic aspiration than in this humanistic gathering place that distills Forty-second Street’s dewy idealism.

This avenue of institutions has a spotty record of saving the world from itself. The UN has allowed innumerable atrocities and wars to rage unchecked, including the latest Syrian calamity. The Daily News has spent much of the last half century threatening to go out of business. The national passenger-train system that fed Grand Central Terminal dried up years ago; today, millions of cars despoil the environment instead. And critics regularly accuse the New York Public Library of hastening a bookless future by forging blindly into the digital age. At the same time, the architectural legacy of massive purpose-built monuments has demonstrated an impressive ability to adapt. This is a city that can be pitiless toward age: west of Sixth Avenue, Forty-second Street has almost entirely remade itself in the last few decades, preserving a few token theaters wedged between towers of glass. East of Sixth, though, the stone metropolis has survived, partly because the landmarks law protects it, but also because buildings that were once advanced and daring have remained doggedly useful as they age. Not every monument to progress can do that: Fire doomed the Crystal Palace; the city’s voracious need for water first created the Croton Reservoir and later made it obsolete. But taken together, the behemoths of Forty-second Street proclaim this city’s nimbleness, its ability to navigate the chaotic present without jettisoning either its history or its dreams.