Flanders

- Bruges

- Ostend and the coast

- Veurne and around

- Diksmuide

- Ieper and around

- Poperinge

- Kortrijk

- Oudenaarde

- Ghent

The Flemish-speaking provinces of West Vlaanderen and Oost Vlaanderen (West Flanders and East Flanders) roll east from the North Sea coast, stretching out towards Brussels and Antwerp. With the exception of the range of low hills around Oudenaarde and the sea dunes along the coast, Flanders is well-nigh pancake-flat, a wide-skied landscape seen at its best in its quieter recesses, where poplar trees and whitewashed farmhouses decorate sluggish canals. There are also many reminders of Flanders’ medieval greatness, beginning with the ancient and fascinating cloth cities of Bruges and Ghent, both of which hold marvellous collections of early Flemish art.

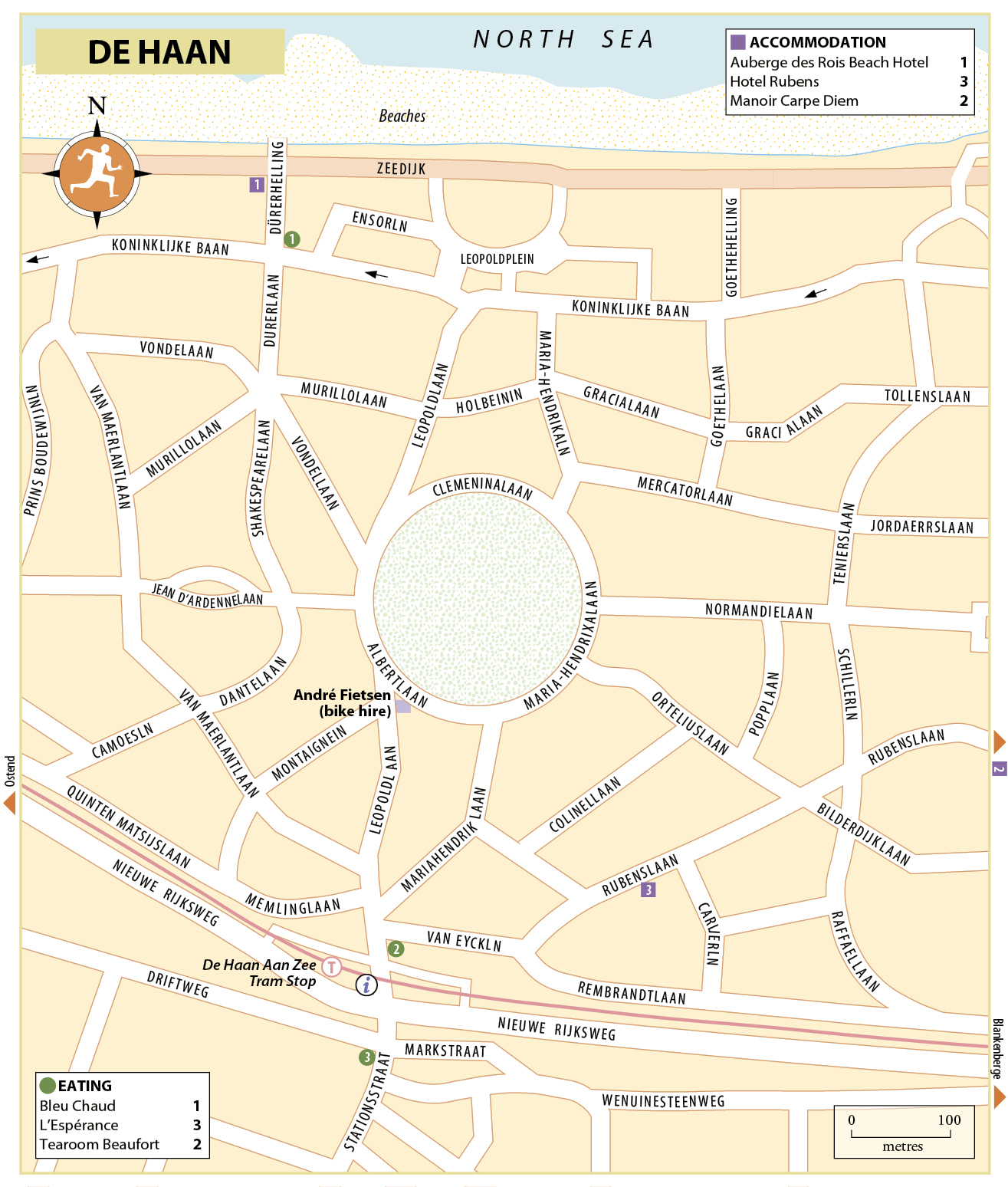

Less familiar is the region’s clutch of intriguing smaller towns, most memorably Oudenaarde, which has a delightful town hall and is famed for its tapestries; Kortrijk, with its classic small-town charms; and Veurne, whose main square is framed by a beguiling medley of fine old buildings. There is also, of course, the legacy of World War I. By 1915, the trenches extended from the North Sea coast to Switzerland, cutting across West Flanders via Diksmuide and Ieper, and many of the key engagements of the war were fought here. Every year hundreds of visitors head for Ieper (formerly Ypres) to see the numerous cemeteries and monuments in and around the town – poignant reminders of what proved to be a desperately pointless conflict. Not far from the battlefields, the Belgian coast is beach territory, an almost continuous stretch of golden sand that is crowded with tourists every summer. An excellent tram service connects all the major seaside resorts, and although a lot of the development has been crass, cosy De Haan has kept much of its late nineteenth-century charm. The largest town on the coast is Ostend, a lively seaside resort sprinkled with popular bars and restaurants, the pick of which sell a wonderful range of seafood.

ostend beach

Highlights

1 Bruges By any measure, Bruges is one of western Europe’s most beautiful cities, its jangle of ancient houses overlooking a cobweb of picturesque canals.

2 Ostend beach The Belgian coast boasts a first-rate sandy beach and Ostend has an especially fine slice.

3 Ieper Flanders witnessed some of the worst battles of World War I, and Ieper is dotted with the sad and mournful reminders.

4 Flemish tapestries Small-town Oudenaarde was once famous for its tapestries, and a superb selection is on display here today.

5 Ghent’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb This wonderful Jan van Eyck painting is absolutely unmissable.

Brief history

As early as the thirteenth century, Flanders was one of the most prosperous parts of Europe, with an advanced, integrated economy dependent on the cloth trade with England. The boom times lasted a couple of centuries, but by the sixteenth century, with trade slipping north towards the Netherlands and England’s cloth manufacturers beginning to undermine Flanders’ economic base, the region was in decline. The speed of the collapse was accelerated by religious wars, for though the great Flemish towns were by inclination Protestant, their counts, kings and queens were Catholic. Flanders sank into poverty and decay, a static, priest-ridden and traditional society where nearly every aspect of life was controlled by decree, and only three percent of the population could read or write.

With precious little say in the matter, the Flemish peasantry of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw their lands crossed and re-crossed by the armies of the Great Powers, for it was here that the relative fortunes of dynasties and nations were decided. Only with Belgian independence did the situation begin to change: the towns started to industrialize, tariffs protected the cloth industry, Zeebrugge was built and Ostend was modernized, all in a flurry of activity that shook Flanders from its centuries-old torpor. This steady progress was severely interrupted by the German occupations of both world wars, but Flanders has emerged prosperous, its citizens maintaining a distinctive cultural and linguistic identity, often in sharp opposition to their Walloon (French-speaking) neighbours.

Bruges

Passing through BRUGES in 1820, William Wordsworth declared that this was where he discovered “a deeper peace than in deserts found”. Perhaps inevitably, crowds tend to overwhelm the place today – its reputation as a perfectly preserved medieval city has made it the most popular tourist destination in Belgium – but you’d be mad to come to Flanders and miss it: the museums of Bruges hold some of the country’s finest collections of Flemish art, and its intimate, winding streets, woven around a skein of narrow canals and lined with gorgeous ancient buildings, live up to even the most inflated hype.

Wordsworth was neither the first nor the last Victorian to fall in love with Bruges; by the 1840s there was a substantial British colony here, its members enraptured by the city’s medieval architecture and air of lost splendour. Neither were the expatriates slow to exercise their economic muscle, applying an architectural Gothic Revival brush to parts of the city that weren’t “medieval” enough. Time and again, they intervened in municipal planning decisions, allying themselves to like-minded Flemings in a movement that changed, or at least modified, the face of the city. Thus, Bruges is not the perfectly preserved medieval city of much tourist literature, but rather a clever, frequently seamless combination of medieval original and nineteenth- and sometimes twentieth-century additions.

The obvious place to start an exploration of the city is the two principal squares: the Markt, overlooked by the mighty belfry, and the Burg, flanked by the city’s most impressive architectural ensemble. Almost within shouting distance are the three main museums, the pick of them being the Groeninge, which offers a wonderful sample of early Flemish art. Another short hop brings you to St-Janshospitaal and the important paintings of the fifteenth-century artist Hans Memling, as well as Bruges’ most impressive churches, the Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk and St-Salvatorskathedraal. Further afield, the gentle canals and maze-like cobbled streets of eastern Bruges – stretching out from Jan van Eyckplein – are extraordinarily pretty. Here, as elsewhere in the centre, the most characteristic architectural feature is the crow-step gable, popular from the fourteenth to the eighteenth century and revived by the restorers of the 1880s, but there are also expansive Georgian-style mansions and humble, homely cottages. Time and again the eye is surprised by the subtle variety of the cityscape, featuring everything from intimate arched doorways and bendy tiled roofs to wonky chimneys and a bevy of discreet shrines and miniature statues.

Brief history

Bruges started out as a ninth-century fortress built by the warlike first count of Flanders, Baldwin Iron Arm, who was intent on defending the Flemish coast from Viking attack. The settlement prospered, and by the fourteenth century it shared effective control of the cloth trade with its two great rivals, Ghent and Ypres (now Ieper), turning high-quality English wool into clothing that was exported all over the known world. An immensely profitable business, it made the city a focus of international trade, and at its peak the town was a key member of – and showcase for the products of – the Hanseatic League, the most powerful economic alliance in medieval Europe. Through the harbours and docks of Bruges, Flemish cloth and Hansa goods were exchanged for hogs from Denmark, spices from Venice, hides from Ireland, wax from Russia, gold and silver from Poland and furs from Bulgaria. The business of these foreign traders was protected by no fewer than 21 consulates, and the city developed a wide range of support services, including banking, money-changing and maritime insurance.

Trouble and strife

Despite (or because of) this lucrative state of affairs, Bruges was dogged by war. Its weavers and merchants were dependent on the goodwill of the kings of England for the proper functioning of the wool trade, but their feudal overlords, the counts of Flanders, and their successors, the dukes of Burgundy (from 1384), were vassals of the rival king of France. Although some of the dukes and counts were strong enough to defy their king, most felt obliged to obey his orders and thus take his side against the English when the two countries were at war. This conflict of interests was compounded by the designs the French monarchy had on the independence of Bruges itself. Time and again, the French sought to assert control over the cities of West Flanders, but more often than not they encountered armed rebellion. In Bruges, Philip the Fair precipitated the most famous insurrection at the beginning of the fourteenth century. Philip and his wife, Joanna of Navarre, had held a grand reception in Bruges, but it had only served to feed their envy. In the face of the city’s splendour, Joanna moaned, “I thought that I alone was Queen, but here in this place I have six hundred rivals.” The opportunity to flex royal muscles came shortly afterwards when the city’s guildsmen flatly refused to pay a new round of taxes. Enraged, Philip dispatched an army to restore order and garrison the town, but at dawn on Friday May 18, 1302, a rebellious force of Flemings crept into the city and massacred Philip’s sleepy army – an occasion later known as the Bruges Matins: anyone who couldn’t correctly pronounce the Flemish shibboleth schild en vriend (“shield and friend”) was put to the sword. There is a statue celebrating the leaders of the insurrection – Jan Breydel and Pieter de Coninck – in the Markt.

Decline and revival

The Habsburgs, who inherited Flanders – as well as the rest of present-day Belgium and the Netherlands, in 1482 – chipped away at the power of the Flemish cities, no one more so than Emperor Charles V. As part of his policy, Charles favoured Antwerp at the expense of Flanders and, to make matters worse, the Flemish cloth industry began its long decline in the 1480s. Bruges was especially badly hit and, as a sign of its decline, failed to dredge the silted-up River Zwin, the town’s trading lifeline to the North Sea. By the 1510s, the stretch of water between Sluis and Damme was only navigable by smaller ships, and by the 1530s the city’s sea trade had collapsed completely. Bruges simply withered away, its houses deserted, its canals empty and its money spirited north with the merchants. Some four centuries later, Georges Rodenbach’s novel Bruges-la-Morte alerted well-heeled Europeans to the town’s aged, quiet charms, and Bruges – frozen in time – escaped damage in both world wars to emerge as the perfect tourist destination.

The Markt

At the heart of Bruges is the Markt, an airy open space edged on three sides by rows of gabled buildings and with horse-drawn buggies clattering over the cobbles. The burghers of nineteenth-century Bruges were keen to put something suitably civic in the middle of the square and the result was the conspicuous monument to the leaders of the Bruges Matins: Pieter de Coninck, of the guild of weavers, and Jan Breydel, dean of the guild of butchers. Standing close together, they clutch the hilt of the same sword, their faces turned to the south in slightly absurd poses of heroic determination.

The biscuit-tin buildings flanking much of the Markt form a charming architectural ensemble, their mellow ruddy-brown brick shaped into a long series of crow-step gables, each slightly different from its neighbour. Most are late nineteenth- or even early twentieth-century re-creations – or re-inventions – of older buildings, though the old provincial courthouse hogging the east side of the square breaks aesthetic ranks, its thunderous neo-Gothic facade of 1878 announced by a brace of stone lions.

Belfort

Markt • Daily 9.30am–6pm, last admission 5pm • €10 • ![]() 050 44 87 43,

050 44 87 43, ![]() visitbruges.be • Entry via the Hallen

visitbruges.be • Entry via the Hallen

Filling out the south side of the Markt, the mighty Belfort was long a potent symbol of civic pride and municipal independence, its distinctive octagonal lantern visible far and wide across the surrounding polders. The Belfort was begun in the thirteenth century, when the town was at its richest and most extravagant, but it has had a blighted history. The original wooden version was struck by lightning and burned to the ground in 1280. Its brick replacement received its octagonal stone lantern and a second wooden spire in the 1480s, but the new spire was lost to a thunderstorm a few years later. Undeterred, the Flemings promptly added a third spire, though when this went up in smoke in 1741 the locals gave up, settling for the present structure, with the addition of a stone parapet in 1822. Few would say the Belfort is good-looking – it’s large and really rather clumsy – but it does have a certain ungainly charm, though this was lost on G.K. Chesterton, who described it as “an unnaturally long-necked animal, like a giraffe”.

The belfry staircase begins innocuously enough, but it gets steeper and much narrower as it nears the top. On the way up, it passes several mildly interesting chambers, beginning with the Treasury Room, where the town charters and money chest were locked for safe keeping. Here also is an iron trumpet with which a watchman could warn the town of a fire outbreak – though given the size of the instrument, it’s hard to believe this was very effective. Further up is the Carillon Chamber, where you can observe the slow turning of the large spiked drum that controls the 47 bells of the municipal carillon. The city still employs a full-time bell-ringer – you’re likely to see him fiddling around in the Carillon Chamber – who puts on regular carillon concerts (Wed, Sat & Sun at 11am; plus mid-June to mid-Sept Mon & Wed at 9pm). A few stairs up from here and you emerge onto the roof, which offers fabulous views, especially in the late afternoon when the warm colours of the city are at their deepest.

Hallen

Markt • Open access • Free

Now used for temporary exhibitions, the Hallen at the foot of the belfry is another much-restored thirteenth-century edifice, its style and structure modelled on the Lakenhalle in Ieper. In the middle, overlooked by a long line of galleries, is a rectangular courtyard, which originally served as the city’s principal market, its cobblestones once crammed with merchants and their wares. On the north side of the courtyard, up a flight of steps, is the entrance to the belfry.

The Burg

From the east side of the Markt, Breidelstraat leads through to the city’s other main square, the Burg, named after the fortress built here by the first count of Flanders, Baldwin Iron Arm, in the ninth century. The fortress disappeared centuries ago, but the Burg long remained the centre of political and ecclesiastical power with the Stadhuis (which has survived) on one side and St-Donaaskathedraal (which hasn’t) on the other. The French army destroyed the cathedral in 1799 and, although the foundations were laid bare in the 1950s, they were promptly re-interred – they lie in front of and underneath the Crowne Plaza Hotel.

Heilig Bloed Basiliek

Burg • April–Oct daily 9.30am–12.30pm & 2–5.30pm; Nov–March Mon, Tues & Thurs–Sun 9.30am–12.30pm & 2–5.30pm, Wed 9.30am–12.30pm • Basilica free; Treasury €2.50 • ![]() 050 33 67 92,

050 33 67 92, ![]() holyblood.com

holyblood.com

The southern half of the Burg is overseen by the city’s finest group of buildings, beginning on the right with the Heilig Bloed Basiliek (Basilica of the Holy Blood), named after the holy relic that found its way here in the Middle Ages. The church divides into two parts. Tucked away in the corner, the lower chapel is a shadowy, crypt-like affair, originally built at the beginning of the twelfth century to shelter another relic, that of St Basil, one of the great figures of the early Greek Church. The chapel’s heavy and simple Romanesque lines are decorated with just one relief, carved above an interior doorway and showing the baptism of Basil in which a strange giant bird, representing the Holy Spirit, plunges into a pool of water.

Next door, approached up a wide, low-vaulted, curving staircase, the upper chapel was built a few years later, but has been renovated so frequently that it’s impossible to make out the original structure – and the nineteenth-century decoration is gaudy-kitsch. That said, the upper chapel does house a magnificent silver tabernacle gifted to Bruges in 1611 by Albert and Isabella of Spain to hold the rock-crystal phial of the Holy Blood. One of the holiest relics in medieval Europe, the phial purports to contain a few drops of blood and water washed from the body of Christ by Joseph of Arimathea. Local legend asserts that it was the gift of Diederik d’Alsace, a Flemish count who distinguished himself by his bravery during the Second Crusade and was given the phial by a grateful patriarch of Jerusalem in 1150. It is, however, rather more likely that the relic was acquired during the sacking of Constantinople in 1204, when the Crusaders simply ignored their collective job description and robbed and slaughtered the Byzantines instead – hence the historical invention. Whatever the truth, after several weeks in Bruges, the relic was found to be dry, but thereafter it proceeded to liquefy every Friday at 6pm until 1325, a miracle attested to by all sorts of church dignitaries, including Pope Clement V.

The phial of the Holy Blood is still venerated and, despite modern scepticism, reverence for it remains strong. It’s sometimes available for visitors to touch under the supervision of a priest inside the chapel, and on Ascension Day (mid-May) it’s carried through the town centre in a colourful but solemn procession, the Heilig-Bloedprocessie, a popular event for which grandstand tickets are sold at the main tourist information office.

The treasury

The shrine that holds the phial of the Holy Blood during the Heilig-Bloedprocessie is displayed in the tiny Schatkamer (treasury), next to the upper chapel. Dating to 1617, it’s a superb piece of work, the gold and silver superstructure encrusted with jewels and decorated with tiny religious figures. The treasury also contains an incidental collection of ecclesiastical bric-a-brac plus a handful of old paintings. Look out also for the faded strands of a locally woven seventeenth-century tapestry depicting St Augustine’s funeral, the sea of helmeted heads, torches and pikes that surround the monks and abbots very much a Catholic view of a muscular State supporting a holy Church.

Stadhuis

Burg • Daily 9.30am–5pm • €4 including the Renaissancezaal • ![]() 050 44 87 43,

050 44 87 43, ![]() visitbruges.be

visitbruges.be

Just to the left of the basilica, the Stadhuis has a beautiful fourteenth-century sandstone facade, though its Art Deco-ish statues, mostly of the counts and countesses of Flanders, are modern replacements for those destroyed by the occupying French army in 1792. Inside, a flight of stairs climbs up to the magnificent Gothic Hall, dating from 1400 and the setting for the first meeting of the States General (parliamentary assembly) in 1464. The ceiling – dripping pendant arches like decorated stalactites – has been restored in a vibrant mixture of maroon, dark brown, black and gold. The ribs of the arches converge in twelve circular vault-keys, picturing scenes from the New Testament. These are hard to see without binoculars, but down below – and much easier to view – are the sixteen gilded corbels that support them, representing the months and the four elements. The frescoes around the walls were commissioned in 1895 to illustrate the history of the town – or rather history as the council wanted to recall it. The largest scene, commemorating the victory over the French at the Battle of the Golden Spurs in 1302, has lots of noble knights hurrahing, though it’s hard to take this seriously when you look at the dogs, one of which clearly has a mismatch between its body and head.

Renaissancezaal ’t Brugse Vrije

Burg • Daily 9.30am–12.30pm & 1.30–5pm • €4 including Stadhuis • ![]() 050 44 87 43,

050 44 87 43, ![]() visitbruges.be

visitbruges.be

Next door but one to the Stadhuis, pop into the Landhuis van het Brugse Vrije (Mansion of the Liberty of Bruges), a comparatively demure building, where just one room has survived from the original fifteenth-century structure. This, the Schepenkamer (Aldermen’s Room), now known as the Renaissancezaal ’t Brugse Vrije (Renaissance Hall of the Liberty of Bruges), is dominated by an enormous marble and oak chimneypiece, a superb example of Renaissance carving completed in 1531 to celebrate the defeat of the French at Pavia six years earlier and the advantageous Treaty of Cambrai that followed. A paean of praise to the Habsburgs, the work features the Emperor Charles V and his Austrian and Spanish relatives, though it’s the trio of bulbous codpieces that really catches the eye. The alabaster frieze running below the carvings was a caution for the Liberty’s magistrates, who held their courts here. In four panels, it relates the then-familiar biblical story of Susanna, in which – in the first panel – two old men surprise her bathing in her garden and threaten to accuse her of adultery if she resists their advances. Susanna does just that, and the second panel shows her in court. In the third panel, Susanna is about to be put to death, Daniel, interrogates the two men and uncovers their perjury. Susanna is acquitted and, in the final scene, the two men are stoned to death.

The Vismarkt and around

From the arch beside the Stadhuis, Blinde Ezelstraat (Blind Donkey Street) leads south across one of the city’s canals to the sombre eighteenth-century Doric colonnades of the Vismarkt (fish market), which is still in use by a handful of traders today. The fish sellers have done rather better than the tanners and dyers who used to work in neighbouring Huidenvettersplein. Both disappeared long ago and nowadays tourists converge on this picturesque square in their droves, holing up in its bars and restaurants and snapping away at the postcard-perfect views of the belfry from the adjacent Rozenhoedkaai. From here, it’s footsteps to the Dijver, which tracks along the canal passing the path to the first of the city’s main museums, the Groeninge.

Groeninge Museum

Dijver 12 • Tues–Sun 9.30am–5pm • €8 including the Arentshuis • ![]() 050 44 87 43,

050 44 87 43, ![]() visitbruges.be

visitbruges.be

The Groeninge Museum possesses one of the world’s finest samples of early Flemish paintings, from Jan van Eyck through to Jan Provoost. The description below details some of the most important works: most if not all should be on display, though note that the collection is regularly rotated. Be sure to pick up a floor plan at reception.

Jan van Eyck

Arguably the greatest of the early Flemish masters, Jan van Eyck (1385–1441) lived and worked in Bruges from 1430 until his death eleven years later. He was a key figure in the development of oil painting, modulating its tones to create paintings of extraordinary clarity and realism. The Groeninge has two gorgeous examples of his work, beginning with the miniature portrait of his wife, Margareta van Eyck, painted in 1439 and bearing his motto, “als ich can” (the best I can do). The painting is very much a private picture and one that had no commercial value, marking a step away from the sponsored art – and religious preoccupations – of previous Flemish artists. The second van Eyck painting is the remarkable Madonna and Child with Canon George van der Paele, a glowing and richly symbolic work with three figures surrounding the Madonna and Child: the kneeling canon, St George (his patron saint) and St Donatian. St George doffs his helmet to salute the infant Christ and speaks by means of the Hebrew word “Adonai” (Lord) inscribed on his armour’s chin-strap, while Jesus replies through the green parrot he holds: folklore asserted that this type of parrot was fond of saying “ave”, the Latin for “welcome” or “hail”. The canon’s face is exquisitely executed, down to the sagging jowls and the bulging blood vessels at his temple, while the glasses and book in his hand add to his air of deep contemplation. Audaciously, van Eyck has broken with tradition by painting the canon among the saints rather than as a lesser figure – a distinct nod to the humanism that was gathering pace in contemporary Bruges.

Rogier van der Weyden

The Groeninge possesses two fine and roughly contemporaneous copies of paintings by Rogier van der Weyden (1399–1464), one-time official city painter to Brussels. The first is a tiny Portrait of Philip the Good, in which the pallor of the duke’s aquiline features, along with the brightness of his hatpin and chain of office, is skilfully balanced by the sombre cloak and hat. The second and much larger painting, St Luke painting the Portrait of Our Lady, is a rendering of a popular if highly improbable legend that Luke painted Mary – thereby becoming the patron saint of painters. The painting is notable for the detail of its Flemish background and the cheeky-chappie smile of the baby Christ.

Hugo van der Goes

One of the most gifted of the early Flemish artists, Hugo van der Goes (d.1482) is a shadowy figure, though it is known that he became master of the painters’ guild in Ghent in 1467. Eight years later, he entered a Ghent priory as a lay brother, perhaps on account of the prolonged bouts of depression that afflicted him. Few of his paintings have survived, but these exhibit a superb compositional balance and a keen observational eye – as in his last work, the luminescent Death of Our Lady. Sticking to religious legend, the Apostles have been miraculously transported to Mary’s deathbed, where, in a state of agitation, they surround the prostrate woman. Mary is dressed in blue, but there are no signs of luxury, reflecting both van der Goes’s asceticism and his polemic – the artist may well have been appalled by the church’s love of glitter and gold.

Hans Memling

Hans Memling (1430–94) is represented by a pair of Annunciation panels from a triptych – gentle, romantic representations of an angel and Mary in contrasting shades of grey. Here also is Memling’s Moreel Triptych, in which the formality of the design is offset by the warm colours and the gentleness of the detail – St Giles strokes the fawn and the knight’s hand lies on the donor’s shoulder. The central panel depicts three saints – two monkish figures to either side of St Christopher, who carries the infant Jesus – and the side panels show the donors and their sixteen children. There are more Memling paintings in Bruges at the St-Janshospitaal.

Gerard David

Born near Gouda in the Netherlands, Gerard David (c.1460–1523) moved to Bruges in his early twenties. Soon admitted to the local painters’ guild, he quickly rose through the ranks, becoming the city’s leading artistic light after the death of Memling. Official commissions rained in on David, mostly for religious paintings, which he approached in a formal manner but with a fine eye for detail. The Groeninge holds two fine examples of his work, starting with the Baptism of Christ Triptych, in which a boyish, lightly bearded Christ is depicted as part of the Holy Trinity in the central panel. There’s also one of David’s few secular ventures, the intriguing Judgement of Cambyses, painted on two large oak panels. Based on a Persian legend related by Herodotus, the first panel’s background shows the corrupt judge Sisamnes accepting a bribe, with his subsequent arrest by grim-faced aldermen filling the rest of the panel. The aldermen crowd in on Sisamnes with a palpable sense of menace and, as the king sentences him to be flayed alive, a sweaty look of fear sweeps over the judge’s face. In the gruesome second panel the king’s servants carry out the judgement, applying themselves to the task with clinical detachment. Behind, in the top right corner, the fable is completed with the judge’s son dispensing justice from his father’s old chair, which is now draped with Sisamnes’s flayed skin. Completed in 1498, the painting was hung in the council chamber by the city burghers to encourage honesty among its magistrates.

Hieronymus Bosch

The Groeninge also holds a Last Judgement by Hieronymus Bosch’s (1450–1516), a trio of oak panels crammed with mysterious beasts, microscopic mutants and scenes of awful cruelty – men boiled in a pit or cut in half by a giant knife. It looks like unbridled fantasy, but in fact the scenes were read as symbols, a sort of strip cartoon of legend, proverb and tradition. Indeed, Bosch’s religious orthodoxy is confirmed by the appeal his work had for that most Catholic of Spanish kings, Philip II.

Jan Provoost

There’s more grim symbolism in Jan Provoost’s (1465–1529) striking The Miser and Death, which portrays the merchant with his money in one panel, trying desperately to pass a promissory note to the grinning skeleton in the next. Provoost’s career was typical of many of the Flemish artists of the early sixteenth century. Initially he worked in the Flemish manner, his style greatly influenced by Gerard David, but from about 1521 his work was reinvigorated by contact with the German painter and engraver Albrecht Dürer, who had himself been inspired by the artists of the early Italian Renaissance. Provoost moved around too, working in Valenciennes and Antwerp, before settling in Bruges in 1494.

Pieter Pourbus

The Groeninge’s collection of late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century paintings isn’t especially strong, but there’s enough to discern the period’s watering down of religious themes in favour of more secular preoccupations. Pieter Pourbus (1523–84) is well represented by a series of austere and often surprisingly unflattering portraits of the movers and shakers of his day. There’s also his Last Judgement, a much larger but atypical work, crammed with muscular men and fleshy women; completed in 1551, its inspiration came from Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel. Born in Gouda, Pourbus moved to Bruges in his early twenties, becoming the leading local portraitist of his day as well as squeezing in work as a civil engineer and cartographer.

The Symbolists

There is a small but significant collection of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Belgian art at the Groeninge. One obvious highlight is the work of the Symbolist Fernand Khnopff (1858–1921), who is represented by Secret Reflections, not perhaps one of his better paintings, but interesting in so far as its lower panel – showing St Janshospitaal reflected in a canal – confirms one of the movement’s favourite conceits: “Bruges the dead city”. This was inspired by Georges Rodenbach’s novel Bruges-la-Morte, a highly stylized muse on love and obsession first published in 1892. The book boosted the craze for visiting Bruges, the so-called “dead city” where the novel’s action unfolds. The upper panel of Khnopff’s painting is a play on appearance and desire, but it’s pretty feeble, unlike his later attempts, in which he painted his sister, Marguerite, again and again, using her refined, almost plastic beauty to stir a vague sense of passion – for him she was desirable and unobtainable in equal measure.

The Expressionists

The museum has a healthy sample of the work of the talented Constant Permeke (1886–1952). Wounded in World War I, Permeke’s grim wartime experiences helped him develop a distinctive Expressionist style in which his subjects – usually agricultural workers, fishermen and so forth – were monumental in form, but invested with sombre, sometimes threatening, emotion. His charcoal drawing the Angelus is a typically dark and earthy representation of Belgian peasant life dated to 1934. In a similar vein is the enormous Last Supper by Gustave van de Woestijne (1881–1947), another excellent example of Belgian Expressionism, with Jesus and the disciples, all elliptical eyes and restrained movement, trapped within prison-like walls.

The Surrealists

The Groeninge owns a clutch of works by the inventive Marcel Broodthaers (1924–76), most notably his tongue-in-cheek (and very Belgian) Les Animaux de la Ferme. René Magritte (1898–1967;) appears too, in his characteristically unnerving The Assault, while Paul Delvaux (1897–1994) features in the spookily stark Surrealism of his Serenity. Delvaux has a museum all to himself in St-Idesbald.

Arentshuis

Dijver 16 • Tues–Sun 9.30am–5pm • €4 • ![]() 050 44 87 43,

050 44 87 43, ![]() visitbruges.be

visitbruges.be

The Arentshuis occupies an attractive eighteenth-century mansion with a stately portico-framed entrance. Now a museum, the interior is divided into two separate sections: the ground floor is given over to temporary exhibitions, usually of fine art, while the Brangwyn Museum upstairs displays the moody sketches, etchings, lithographs, studies and paintings of the much-travelled artist Sir Frank Brangwyn (1867–1956). Born in Bruges of Welsh parents, Brangwyn flitted between Britain and Belgium, donating this sample of his work to his native town in 1936. Apprenticed to William Morris in the early 1880s and an official UK war artist in World War I, Brangwyn was nothing if not versatile, turning his hand to several different media, though his forceful drawings and sketches are much more appealing than his paintings, which often slide into sentimentality.

Arentspark

The Arentshuis stands in the north corner of the pocket-sized Arentspark, whose pair of forlorn stone columns are all that remains of the Waterhalle, a large trading hall which once straddled the most central of the city’s canals but was demolished in 1787 after the canal was covered over. Also in the Arentspark is the tiniest of humpbacked bridges – St Bonifaciusbrug – whose stonework is framed against a tumble of antique brick houses. One of Bruges’ most picturesque (and photographed) spots, the bridge looks like the epitome of everything medieval, but in fact it was built in 1910.

Gruuthuse Museum

Dijver 17 • Closed for refurbishment until 2019 • ![]() 050 44 87 43,

050 44 87 43, ![]() visitbruges.be

visitbruges.be

The Gruuthuse Museum is located inside a rambling mansion that dates from the fifteenth century. The building is a fine example of civil Gothic architecture and it takes its name from the house owners’ historical right to tax the gruit, the dried herb and flower mixture once added to barley during the beer-brewing process to improve the flavour. The last lord of the Gruuthuse died in 1492 and, after many twists and turns, the mansion was turned into a museum to hold a hotchpotch of Flemish fine, applied and decorative arts, mostly from the medieval and early modern periods. The museum’s most famous artefact is a polychromatic terracotta bust of a youthful Emperor Charles V and its most unusual feature is the oak-panelled oratory that juts out from the first floor to overlook the altar of the Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk next door. A curiously intimate room, the oratory allowed the lords of the gruit to worship without leaving home – a real social coup.

Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk

Mariastraat • Mon–Sat 9.30am–5pm, Sun 1.30–5pm • Free, but chancel €6 • ![]() 050 44 87 43,

050 44 87 43, ![]() visitbruges.be

visitbruges.be

The Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk (Church of Our Lady) is a rambling shambles of a building, a clamour of different dates and styles whose brick spire is – at 115.50m – the highest brick tower in Belgium. Entered from the south, the nave was three hundred years in the making, an architecturally discordant affair, whose thirteenth-century grey-stone central aisle is the oldest part of the church. The central aisle blends in with the south aisle but the later, fourteenth-century north aisle doesn’t mesh at all – even the columns aren’t aligned. This was the result of changing fashions, not slapdash work: the High Gothic north aisle was intended to be the start of a complete remodelling of the church, but the money ran out before the project was finished. In the south aisle is the church’s most acclaimed objet d’art, a delicate marble Madonna and Child by Michelangelo. Purchased by a Bruges merchant, this was the only one of Michelangelo’s works to leave Italy during the artist’s lifetime and it had a significant influence on the painters then working in Bruges, though its present setting – beneath gloomy stone walls and set within a gaudy Baroque altar – is hardly prepossessing.

The chancel

Michelangelo apart, the most interesting part of the church is the chancel, beyond the heavy-duty black and white marble rood screen. Here you’ll find the mausoleums of Charles the Bold and his daughter Mary of Burgundy, two exquisite examples of Renaissance artistry, their side panels decorated with coats of arms connected by the most intricate of floral designs. The royal figures are enhanced in the detail, from the helmet and gauntlets placed gracefully by Charles’ side to the pair of watchful dogs nestled at Mary’s feet. Oddly enough, the hole dug by archeologists beneath the mausoleums during the 1970s to discover who was actually buried here was never filled in, so you can see the burial vaults of several unknown medieval dignitaries, three of which have now been moved across to the Lanchals Chapel.

Lanchals Chapel

Just across the ambulatory from the mausoleums is the Lanchals Chapel, which holds the imposing Baroque gravestone of Pieter Lanchals, a one-time Habsburg official who had his head lopped off by the citizens of Bruges for corruption in 1488. In front of the Lanchals gravestone are the three relocated medieval burial vaults moved across from beneath the mausoleums, each plastered with lime mortar. The inside walls of the vaults sport brightly coloured grave frescoes, a type of art which flourished hereabouts from the late thirteenth to the middle of the fifteenth century. The iconography is fairly consistent, with the long sides mostly bearing one, sometimes two, angels apiece, and most of the angels are shown swinging thuribles (the vessels in which incense is burnt during religious ceremonies). Typically, the short sides show the Crucifixion and a Virgin and Child. The background decoration is more varied, with crosses, stars and dots all making appearances as well as two main sorts of flower – roses and bluebells. The frescoes were painted freehand and executed at great speed – Flemings were then buried on the day they died – hence the delightful immediacy of the work.

The earthly remains of Charles the Bold and Mary of Burgundy

The last independent rulers of Flanders were Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy, and his daughter Mary of Burgundy, both of whom died in unfortunate circumstances: Charles during the siege of the French city of Nancy in 1477; Mary after a riding accident in 1482. Mary was married to Maximilian, a Habsburg prince and future Holy Roman Emperor, who inherited her territories on her death – thus, at a dynastic stroke, Flanders was incorporated into the Habsburg empire with all the dreadful consequences that would entail.

In the sixteenth century, the Habsburgs relocated to Spain, but they were keen to emphasize their connections with, and historical authority over, Flanders. Nothing did this quite as well as the ceremonial burial – or reburial – of bits of royal body. Mary was safely ensconced in Bruges’s Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk, but the body of Charles was in a makeshift grave in Nancy. The Emperor Charles V, the great grandson of Charles the Bold, had this body exhumed and carried to Bruges, where it was reinterred next to Mary. Or at least he thought he had: there were persistent rumours that the French – the traditional enemies of the Habsburgs – had deliberately handed over a dud skeleton. In the 1970s, archeologists had a bash at solving the mystery by digging beneath Charles and Mary’s mausoleums in the Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk. But among the assorted tombs, they failed to authoritatively identify either the body or even the tomb of Charles. Things ran more smoothly in Mary’s case, however, with her skeleton confirming the known details of her hunting accident. Moreover, buried alongside her was the urn which contained the heart of her son, Philip the Fair, placed here in 1506. More archeological harrumphing over the remains of poor old Charles is likely at some point or another.

St-Janshospitaalmuseum

Mariastraat 38 • Apotheek (Apothecary) Tues–Sun 9.30am–12.30pm & 1.30–5pm; St-Janshospitaalmuseum Tues–Sun 9.30am–5pm • €8 • ![]() 050 44 87 43,

050 44 87 43, ![]() visitbruges.be

visitbruges.be

Opposite the entrance to the Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk is St-Janshospitaal, a sprawling complex that sheltered the sick of mind and body until well into the nineteenth century. The oldest part – at the front on Mariastraat, behind two church-like gable ends – has been turned into the excellent St-Janshospitaalmuseum, while the nineteenth-century annexe, reached along a narrow passageway on the north side of the museum, has been converted into a really rather mundane events and exhibition centre called – rather confusingly – Oud St-Jan. As you stroll down the passageway, you pass the old Apotheek, where one room holds dozens of ex-votos, the other an ancient dispensing counter flanked by dozens of vintage apothecary’s jars.

St-Janshospitaalmuseum occupies the old, stone-arched hospital ward and the adjoining chapel. The first part of the museum explores the historical background to the hospital through documents, paintings and religious objets d’art. Highlights include an enlarged photo of the hospital’s nuns in their full and fancy habits as of 1858 and a pair of sedan chairs used to carry the infirm to the hospital in emergencies. There’s also Jan Beerblock’s The Wards of St Janshospitaal, a minutely detailed painting of the hospital ward as it was in the late eighteenth century, the patients tucked away in row upon row of tiny, cupboard-like beds. Other noteworthy paintings include an exquisite Deposition of Christ, a late fifteenth-century version of an original by Rogier van der Weyden, and a stylish, intimately observed diptych by Jan Provoost that includes images of Christ, the donor (a friar) and a skull.

The Memling collection

The museum also holds six wonderful works by Hans Memling (1433–94). Born near Frankfurt, Memling spent most of his working life in Bruges, where Rogier van der Weyden instructed him. He adopted much of his tutor’s style and stuck to the detailed symbolism of his contemporaries, but his painterly manner was distinctly restrained and often pious and grave. Graceful and warmly coloured, his figures also had a velvet-like quality that greatly appealed to the city’s burghers, whose enthusiasm made Memling a rich man – in 1480 he was listed among the town’s major moneylenders.

Reliquary of St Ursula and two Memling triptychs

Of the Memling works on display in the old hospital ward, the most unusual is the reliquary of St Ursula, comprising a miniature wooden Gothic church painted with the story of St Ursula. Memling condensed the legend into six panels with Ursula and her ten companions landing at Cologne and Basle before reaching Rome at the end of their pilgrimage. Things go badly wrong on the way back: they leave Basle in good order, but are then – in the last two panels – massacred by Huns as they pass through Germany. Memling had a religious point to make, but today it’s the mass of incidental detail that makes the reliquary so enchanting, providing an intriguing evocation of the late medieval world. Close by are two triptychs, a Lamentation and an Adoration of the Magi, in which there’s a gentle nervousness in the approach of the Magi, here shown as the kings of Spain, Arabia and Ethiopia.

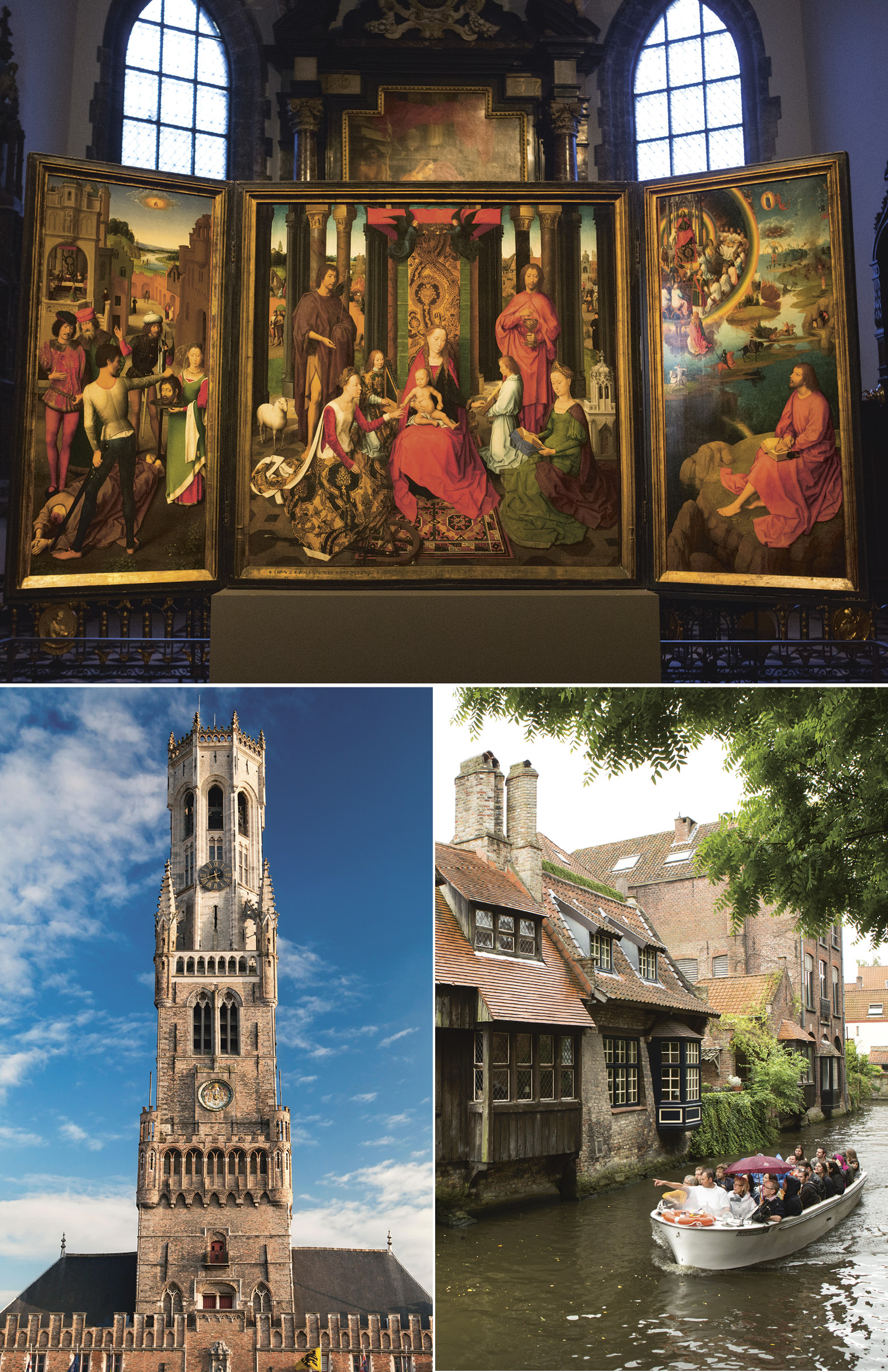

Triptych of St John the Baptist and St John the Evangelist

In the museum’s former chapel is the delightful Mystical Marriage of St Catherine, the middle panel of a large triptych in which St Catherine, who represents contemplation, is shown receiving a ring from the baby Jesus to seal their spiritual union. The complementary side panels depict the beheading of St John the Baptist and a visionary St John the Evangelist writing the Book of Revelation on the bare and rocky island of Patmos. Again, it’s the detail that impresses: between the inner and outer rainbows above the Evangelist, for instance, the prophets play music on tiny instruments – look closely and you’ll spy a lute, a flute, a harp and a hurdy-gurdy.

Virgin and Martin van Nieuwenhove

In a side chapel adjoining the main chapel is the Virgin and Martin van Nieuwenhove diptych, which depicts the eponymous merchant in the full flush of youth and with a hint of arrogance: his lips pout, his hair cascades down to his shoulders and he is dressed in the most fashionable of doublets – by the middle of the 1480s, when the portrait was commissioned, no Bruges merchant wanted to appear too pious. Opposite, the Virgin gets the full stereotypical treatment from the oval face and the almond-shaped eyes through to full cheeks, thin nose and bunched lower lip.

Portrait of a Young Woman

Also in the side chapel, Memling’s skill as a portraitist is demonstrated to exquisite effect in his Portrait of a Young Woman, where the richly dressed subject stares dreamily into the middle distance, her hands – in a superb optical illusion – seeming to clasp the picture frame. The lighting is subtle and sensuous, with the woman set against a dark background, her gauze veil dappling the side of her face. A high forehead was then considered a sign of great womanly beauty, so her hair is pulled right back and was probably plucked – as are her eyebrows. There’s no knowing who the woman was, but in the seventeenth century her fancy headgear convinced observers that she was one of the legendary sibyls who predicted Christ’s birth; so convinced were they that they added the cartouche in the top left-hand corner, describing her as Sibylla Sambetha – and the painting is often referred to by this name.

St-Salvatorskathedraal

Steenstraat • Mon–Fri 10am–1pm & 2–5.30pm, Sat 10am–1pm & 2–3.30pm, Sun 11.30am–noon & 2–5pm • ![]() 050 33 61 88,

050 33 61 88, ![]() sintsalvator.be

sintsalvator.be

The high and mighty St-Salvatorskathedraal (Holy Saviour Cathedral) is a bulky Gothic edifice that mostly dates from the late thirteenth century, though the ambulatory was added some two centuries later. A parish church for most of its history, it was only made a cathedral in 1834 following the destruction of St Donatian’s by the French. This change of status prompted lots of ecclesiastical rumblings – nearby Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk was bigger and its spire higher – and when part of St Salvator’s went up in smoke in 1839, the opportunity was taken to make its tower higher and grander in a romantic rendition of the Romanesque style.

The nave and porch

Slowly emerging from a seemingly interminable restoration, the cathedral’s nave remains a cheerless, cavernous affair despite lashings of new paint. The star turn is the set of eight paintings by Jan van Orley displayed in the transepts. Commissioned in the 1730s, the paintings were used for the manufacture of a matching set of tapestries from a Brussels workshop and, remarkably enough, these have survived too and hang in sequence in the choir and nave. Each of the eight scenes is a fluent, dramatic composition featuring a familiar episode from the life of Christ – from the Nativity to the Resurrection – complete with a handful of animals, including a remarkably determined Palm Sunday donkey. The tapestries are actually mirror images of the paintings as the weavers worked with the rear of the tapestries uppermost on their looms; the weavers also had sight of the tapestry paintings – or rather cartoon copies, as the originals were too valuable to be kept beside the looms. Adjoining the nave, in the floor of the porch behind the old main doors, look out also for the six recently excavated tombs, whose interior walls are decorated with grave frescoes that follow the same design as those in the Lanchals Chapel.

The treasury

The cathedral treasury (Schatkamer) occupies the adjoining neo-Gothic chapterhouse, whose cloistered rooms are packed with ecclesiastical bits and pieces, from religious paintings and statues through to an assortment of reliquaries, vestments and croziers. The labelling is poor, however, so it’s a good idea to pick up the English-language mini-guide at the entrance. Room B holds the treasury’s finest painting, a gruesome, oak-panel triptych, The Martyrdom of St Hippolytus, by Dieric Bouts (1410–75) and Hugo van der Goes (d. 1482). The right panel depicts the Roman Emperor Decius, a notorious persecutor of Christians, trying to persuade the priest Hippolytus to abjure his faith. He fails, and in the central panel Hippolytus is pulled to pieces by four horses.

The Begijnhof

Begijnhof • Daily 6.30am–6.30pm • Free • ![]() 050 33 00 11,

050 33 00 11, ![]() visitbruges.be

visitbruges.be

Bruges’ tourist throng zeroes in on the Begijnhof, just south of the centre, where a rough circle of old and infinitely pretty whitewashed houses surrounds a central green, which looks a treat in spring, when a carpet of daffodils pushes up between the wind-bent elms. There were once begijnhoven all over Belgium, and this is one of the few to have survived in good nick. They date back to the twelfth century, when a Liège priest – a certain Lambert le Bègue – encouraged widows and unmarried women to live in communities, the better to do pious acts, especially caring for the sick. These communities were different from convents in so far as the inhabitants – the Beguines (begijnen) – did not have to take conventual vows and had the right to return to the secular world if they wished. Margaret, Countess of Flanders, founded Bruges’ begijnhof in 1245, and although most of the houses now standing date from the eighteenth century, the medieval layout has survived intact, preserving the impression of the begijnhof as a self-contained village, with access controlled through two large gates. Almost all of the houses are still in private hands but, with the Beguines long gone, they’re now occupied by a mixture of single, elderly women and Benedictine nuns, whom you’ll see flitting around in their habits, mostly on their way to and from the Begijnhofkerk, a surprisingly large church with a set of gaudy altarpieces.

Begijnenhuisje

Begijnhof 24 • Mon–Sat 10am–5pm, Sun 2.30–5pm • €2

Only one house in the begijnhof is open to the public – the Begijnenhuisje, a small-scale celebration of the simple life of the Beguines comprising a couple of living rooms and a mini-cloister. The prime exhibit is the schapraai, a traditional Beguine’s cupboard, which was a frugal combination of dining table, cutlery cabinet and larder.

Minnewater

Facing the more southerly of the begijnhof ’s two gates is the Minnewater, often hyped as the city’s “Lake of Love”. The tag certainly gets the canoodlers going, but in fact the lake – more a large pond – started life as a city harbour. The distinctive stone lock house at the head of the Minnewater recalls its earlier function, though it’s actually a very fanciful nineteenth-century reconstruction of the medieval original. The Poertoren, on the west bank at the far end of the lake, is more authentic, its brown brickwork dating from 1398 and once forming part of the city wall. This is where the city kept its gunpowder – hence the name, “powder tower”. Beside the Poertoren, a footbridge spans the southern end of the Minnewater to reach the leafy expanse of Minnewaterpark - or you can keep on going along the footpath that threads its way along the old city ramparts, now pleasantly wooded.

Jan van Eyckplein and around

Jan van Eyckplein, a five-minute walk north of the Markt, is one of the prettier squares in Bruges, its cobbles backdropped by the easy sweep of the Spiegelrei canal. The centrepiece of the square is an earnest statue of Jan van Eyck, erected in 1878, while on the north side is the Tolhuis, whose fancy Renaissance entrance is decorated with the coat of arms of the dukes of Luxembourg, who long levied tolls here. The Tolhuis dates from the late fifteenth century, but was extensively remodelled in medieval style in the 1870s, as was the Poortersloge (Merchants’ Lodge; no public entry), whose slender tower pokes up above the rooftops on the west side of the square. Theoretically, any city merchant was entitled to be a member of the Poortersloge, but in fact membership was restricted to the richest and most powerful. An informal alternative to the Stadhuis, it was here that key political and economic decisions were taken – and this was also where local bigwigs could drink and gamble discreetly.

Spiegelrei canal

Running east from Jan van Eyckplein, the Spiegelrei canal was once the heart of the foreign merchants’ quarter, its frenetic quays overlooked by the trade missions of many of the city’s trading partners. The medieval buildings were demolished long ago but they have been replaced by an exquisite medley of architectural styles, from expansive Classical mansions to pirouetting crow-step gables.

Gouden Handrei and around

At the far end of Spiegelrei, a left turn brings you onto one of the city’s loveliest streets, Gouden-Handrei, which – along with its continuation, Spaanse Loskaai – was once the focus of the Spanish merchants’ quarter. The west end of Spaanse Loskaai is marked by the Augustijnenbrug, the city’s oldest surviving bridge, a sturdy three-arched structure dating from 1391. The bridge was built to help the monks of a nearby (and long demolished) Augustinian monastery get into the city centre speedily; the benches set into the parapet were cut to allow itinerant tradesmen to display their goods here.

Spanjaardstraat

Running south from Augustijnenbrug is Spanjaardstraat, another part of the old Spanish enclave. It was here, at no. 9, in a house formerly known as De Pijnappel (The Fir Cone), that the founder of the Jesuits, Ignatius Loyola (1491–1556), spent his holidays while he was a student in Paris – unfortunately the town’s liberality failed to dent Loyola’s nascent fanaticism.

The Adornesdomein

Peperstraat 3 • Mon–Sat 10am–5pm • €7 • ![]() 050 33 88 83,

050 33 88 83, ![]() adornes.org

adornes.org

Beyond the east end of the Spiegelrei canal is an old working-class district, whose simple brick cottages surround the Adornesdomein, a substantial complex of buildings belonging to the wealthy Adornes family, who migrated here from Genoa in the thirteenth century and made a fortune from a special sort of dye fastener. A visit to the domein begins towards the rear of the complex, where a set of humble brick almshouses hold a small museum, which gives the historical low-down on the family. The most interesting figure was the much travelled Anselm Adornes (1424–83), whose roller-coaster career included high-power diplomatic missions to Scotland and being punished for alleged corruption – he was fined and paraded through Bruges dressed only in his underwear.

The Jeruzalemkerk

Anselm Adornes and several of his kinfolk made pilgrimages to the Holy Land and one result is the idiosyncratic Jeruzalemkerk (Jerusalem Church), the main feature of the domein and an approximate copy of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. The church’s interior is on two levels: the lower one is dominated by a large and ghoulish altarpiece, decorated with skulls and ladders, in front of which is the black marble mausoleum of Anselm Adornes and his wife Margaretha – though the only part of Anselm held here is his heart: Anselm was murdered in Scotland, which is where he was buried, but his heart was sent back here to Bruges. There’s more grisliness at the back of the church, where a vaulted chapel holds a replica of Christ’s tomb with an imitation body – it’s down a narrow tunnel behind the iron grating. To either side of the main altar, steps ascend to the choir, which is situated right below the eccentric, onion-domed lantern tower.

Kantcentrum

Balstraat 16 • Mon–Sat 9.30am–5pm; demonstrations Mon–Sat 2–5pm • €5.20, including demonstrations • ![]() 050 33 00 72,

050 33 00 72, ![]() kantcentrum.eu

kantcentrum.eu

The ground floor of the Kantcentrum (Lace Centre), just metres from the Adornesdomein, traces the history of the industry here in Bruges and displays a substantial sample of antique handmade lace. The earliest major piece is an exquisite, seventeenth-century Lenten veil with scenes from the life of Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, and there are also intricate collars, ruffs, fans and sample books. The most fanciful pieces – Chantilly lace especially – mostly date from the late nineteenth century. Belgian lace – or Flanders lace as it was formerly known – was renowned for the fineness of its thread and beautiful motifs and it was once worn in the courts of Brussels, Paris, Madrid and London, with Bruges the centre of its production. Handmade lace reached the peak of its popularity in the early nineteenth century, when hundreds of Bruges women and girls worked as home-based lace-makers. The industry was, however, transformed by the arrival of machine-made lace in the 1840s and, by the end of the century, handmade lace had been largely supplanted, with the lace-makers obliged to work in factories. This highly mechanized industry collapsed after World War I when lace, a symbol of an old and discredited order, suddenly had no place in the wardrobe of most women. Most lace shops in Bruges sell lace manufactured in the Far East, especially China, but upstairs at the Kantcentrum there are demonstrations of handmade lace-making. You can buy pieces here too – or stroll along the street to ’t Apostelientje.

Arrival and departure: bruges

By train & bus The train and adjacent bus station are about 2km southwest of the city centre. Local bus #12 departs for the main square, the Markt, from outside the train station every few minutes; other services stop on the Markt or in the surrounding side streets. A taxi from the train station to the Markt costs about €12.

Destinations by train Brussels (every 20min; 1hr); Ghent (every 20min; 20min); Ostend (every 20min; 15min).

Destinations by bus Damme (#43 Mon–Fri 1 or 2 daily; 30min).

By car The E40, running northwest from Brussels to Ostend, skirts Bruges. Bruges is clearly signed from the E40 and its oval-shaped centre is encircled by the R30 ring road.

Parking Parking in the centre can be a real tribulation; easily the best and most economical option is to use the 24/7 car park by the train station, particularly as the price – €3.50 per day – includes the cost of the bus ride to and from the centre.

getting around

By bus Local buses are operated by De Lijn (![]() 070 22 02 00,

070 22 02 00, ![]() delijn.be). A standard one-way fare costs €3. Tickets are valid for an hour and can be purchased at automatic ticket machines and from the driver. A 24hr city transport pass, the Dagpas, costs €6 (€8 from the driver). There’s a De Lijn information kiosk outside the train station (Mon–Fri 7.30am–5.45pm, Sat 9am–5pm & Sun 10am–5pm).

delijn.be). A standard one-way fare costs €3. Tickets are valid for an hour and can be purchased at automatic ticket machines and from the driver. A 24hr city transport pass, the Dagpas, costs €6 (€8 from the driver). There’s a De Lijn information kiosk outside the train station (Mon–Fri 7.30am–5.45pm, Sat 9am–5pm & Sun 10am–5pm).

By bike Flat as a pancake, Bruges and its environs are a great place to cycle, especially as there are cycle lanes on many of the roads and cycle racks dotted across the centre. There are about a dozen bike rental places in town – tourist information has the full list. The largest is Fietspunt Brugge, beside the train station (April–Sept Mon–Fri 7am–7pm, Sat & Sun 10am–9pm; Oct–March Mon–Fri 7am–7pm; ![]() 050 39 68 26). A standard-issue bike costs €15 per day (€4/hr), plus a refundable deposit of €10.

050 39 68 26). A standard-issue bike costs €15 per day (€4/hr), plus a refundable deposit of €10.

By taxi Bruges has several taxi ranks, including one on the Markt and another outside the train station. Fares are metered – and the most common journey, from the train station to the centre, costs about €12.

information

Tourist information There are three tourist information offices: a small one at the train station (daily 10am–5pm); the main one in the Concertgebouw (Concert Hall) complex, on the west side of the city centre on ’t Zand (Mon–Sat 10am–5pm, Sun 10am–2pm); and a third on the Markt (daily 10am–5pm), in the same building as the ghastly Historium where, allegedly, you can “Experience the magic of the medieval period”. They have a common phone line and website (![]() 050 44 46 46,

050 44 46 46, ![]() visitbruges.be).

visitbruges.be).

City passes A splurge of new (and occasionally tawdry) attractions made Bruges’s old CityCard pass increasingly hard to co-ordinate and as a consequence it was abandoned in 2016. It may or may not be revived, but in the meantime the best you’ll do is the Museum Pass, which is valid for three days, covers entry to all the main museums and costs €20 (12–25-year-olds €15)

Cycling around bruges

Beginning about 2.5km northeast of the Markt, the country lanes on either side of the Brugge-Sluis canal cut across a pretty parcel of land that extends as far as the E34/N49 motorway, about 12km further to the northeast. This rural backwater is ideal cycling country, its green fields crisscrossed by drowsy canals and causeways, each of which is shadowed by poplar trees which quiver and rustle in the prevailing westerly winds. An obvious itinerary – of about 28km – takes in the quaint village of DAMME, which was, in medieval times, Bruges’s main seaport. Thereafter, the Brugge-Sluis carries on east as far as tiny HOEKE, where, just over the bridge and on the north side of the canal, you turn hard left for the narrow causeway – the Krinkeldijk – that wanders straight back in the direction of Bruges. Just over 3km long, the Krinkeldijk drifts across a beguiling landscape of whitewashed farmhouses and deep-green grassy fields before reaching an intersection where you turn left to regain the Brugge–Sluis waterway.

The map you want is the Fietsnetwerk Brugse Ommeland (1:50,000), available from any major bookshop.

clockwise from top St-Janshospitaalmuseum ; CANAL NEAR ST BONIFACIUSBRUG ; Belfort, Bruges

Guided tours and boat trips in and around bruges

Guided tours are big business in Bruges. Tourist information has comprehensive details, but among the many options one long-standing favourite is a horse-drawn carriage ride. Carriages hold a maximum of five, and line up on the Markt (daily 10am–10pm; 30min; €50 per carriage) to offer a short canter around town; demand can outstrip supply, so expect to queue at the weekend. A second favourite is half-hour boat trips along the city’s central canals with boats departing from a number of jetties south of the Burg (March–Nov daily 10am–6pm; €8). Boats leave every few minutes, but long queues still build up during high season, with few visitors seemingly concerned by the canned commentary. In winter (Dec–Feb), there’s a spasmodic service at weekends only.

Quasimodo Tours ![]() 050 37 04 70,

050 37 04 70, ![]() quasimodo.be. Bruges has a small army of tour operators but this is one of the best, running a first-rate programme of excursions both in and around Bruges and out into Flanders. Highly recommended is their “Flanders Field Battlefield” minibus tour of the World War I battlefields near Ieper. Tours cost €67 (under 26 €57), including picnic lunch, and last about eight hours. Reservations required; hotel or train station pick-up can be arranged.

quasimodo.be. Bruges has a small army of tour operators but this is one of the best, running a first-rate programme of excursions both in and around Bruges and out into Flanders. Highly recommended is their “Flanders Field Battlefield” minibus tour of the World War I battlefields near Ieper. Tours cost €67 (under 26 €57), including picnic lunch, and last about eight hours. Reservations required; hotel or train station pick-up can be arranged.

Quasimundo Predikherenstraat 28 ![]() 050 33 07 75,

050 33 07 75, ![]() quasimundo.com. Quasimundo runs several bike tours, starting from the Burg. Their “Bruges by Bike” excursion (March–Oct 1 daily; 2.5hr; €28) zips round the main sights and then explores less-visited parts of the city, while their “Border by Bike” tour (March–Oct 1 daily; 4hr; €28) is a 25km ride out along the poplar-lined canals to the north of Bruges, visiting Damme and Oostkerke with stops and stories along the way. Both are good fun and the price includes mountain-bike and rain-jacket hire; reservations are required.

quasimundo.com. Quasimundo runs several bike tours, starting from the Burg. Their “Bruges by Bike” excursion (March–Oct 1 daily; 2.5hr; €28) zips round the main sights and then explores less-visited parts of the city, while their “Border by Bike” tour (March–Oct 1 daily; 4hr; €28) is a 25km ride out along the poplar-lined canals to the north of Bruges, visiting Damme and Oostkerke with stops and stories along the way. Both are good fun and the price includes mountain-bike and rain-jacket hire; reservations are required.

Accommodation

Bruges has over a hundred hotels, almost two hundred B&Bs and several youth hostels, but still can’t accommodate all its visitors at busy times, especially in the high season (roughly late June to early Sept) and at Christmas – so you’d be well advised to book ahead. Most of the city’s hotels are small – twenty rooms, often fewer – and few are chains. Standards are generally high among the hotels and B&Bs, whereas the city’s hostels are more inconsistent.

Hotels

Adornes St Annarei 26

Adornes St Annarei 26 ![]() 050 34 13 36,

050 34 13 36, ![]() adornes.be; map. Medium-sized three-star in two tastefully converted old Flemish townhouses. Both the public areas and the comfortable bedrooms are decorated in attractive pastel shades, which emphasize the antique charm of the place. The location’s great – at the junction of two canals near the east end of Spiegelrei – and the breakfasts delicious. Also very child-friendly. €135

adornes.be; map. Medium-sized three-star in two tastefully converted old Flemish townhouses. Both the public areas and the comfortable bedrooms are decorated in attractive pastel shades, which emphasize the antique charm of the place. The location’s great – at the junction of two canals near the east end of Spiegelrei – and the breakfasts delicious. Also very child-friendly. €135

Alegria St-Jakobsstraat 34

Alegria St-Jakobsstraat 34 ![]() 050 33 09 37,

050 33 09 37, ![]() alegria-hotel.com; map. Formerly a B&B, this appealing, family-run three-star has a dozen or so large and well-appointed rooms, each decorated in attractive shades of brown, cream and white. The rooms at the back, overlooking the garden, are quieter than those at the front. The owner is a mine of information about where and what to eat, and the hotel is in a central location, near the Markt. €120

alegria-hotel.com; map. Formerly a B&B, this appealing, family-run three-star has a dozen or so large and well-appointed rooms, each decorated in attractive shades of brown, cream and white. The rooms at the back, overlooking the garden, are quieter than those at the front. The owner is a mine of information about where and what to eat, and the hotel is in a central location, near the Markt. €120

Cordoeanier Cordoeaniersstraat 18 ![]() 050 33 90 51,

050 33 90 51, ![]() cordoeanier.be; map. Medium-sized, family-run two-star hotel handily located in a narrow side street a couple of minutes’ walk north of the Burg. Mosquitoes can be a problem here, but the 22 rooms are neat, trim and modern. €95

cordoeanier.be; map. Medium-sized, family-run two-star hotel handily located in a narrow side street a couple of minutes’ walk north of the Burg. Mosquitoes can be a problem here, but the 22 rooms are neat, trim and modern. €95

Europ Augustijnenrei 18 ![]() 050 33 79 75,

050 33 79 75, ![]() hoteleurop.com; map. Three-star hotel in a late nineteenth-century townhouse overlooking a canal about a 5min walk north of the Burg. The public areas are somewhat frumpy and the modern bedrooms distinctly spartan, but the prices are very competitive. €95

hoteleurop.com; map. Three-star hotel in a late nineteenth-century townhouse overlooking a canal about a 5min walk north of the Burg. The public areas are somewhat frumpy and the modern bedrooms distinctly spartan, but the prices are very competitive. €95

De Goezeput Goezeputstraat 29 ![]() 050 34 26 94,

050 34 26 94, ![]() hotelgoezeput.be; map. In a charming location near the cathedral, this enjoyable two-star hotel occupies a thoroughly refurbished eighteenth-century convent. The guest rooms, which vary considerably in size, have been done out in contemporary style in shades of brown and cream, though the entrance, with its handsome wooden beams and staircase, has been left untouched. €95

hotelgoezeput.be; map. In a charming location near the cathedral, this enjoyable two-star hotel occupies a thoroughly refurbished eighteenth-century convent. The guest rooms, which vary considerably in size, have been done out in contemporary style in shades of brown and cream, though the entrance, with its handsome wooden beams and staircase, has been left untouched. €95

Jacobs Baliestraat 1 ![]() 050 33 98 31,

050 33 98 31, ![]() hoteljacobs.be; map. A good budget option, this three-star hotel in a quiet, central location occupies a pleasantly modernized old brick building complete with a precipitous crow-step gable. The twenty-odd rooms are decorated in crisp, modern style, though some are a little small. €95

hoteljacobs.be; map. A good budget option, this three-star hotel in a quiet, central location occupies a pleasantly modernized old brick building complete with a precipitous crow-step gable. The twenty-odd rooms are decorated in crisp, modern style, though some are a little small. €95

Montanus Nieuwe Gentweg 76 ![]() 050 33 11 76,

050 33 11 76, ![]() denheerd.be; map. This four-star hotel occupies a big old house that has been sympathetically modernized with little the decorative over-elaboration of many rivals. The twelve rooms here are large, comfortable and modern – and there are twelve more at the back, in chalet-like accommodation at the far end of the large garden. There’s also an especially appealing room in what amounts to a (cosy and luxurious) garden shed. The garden also accommodates an up-market restaurant. €120

denheerd.be; map. This four-star hotel occupies a big old house that has been sympathetically modernized with little the decorative over-elaboration of many rivals. The twelve rooms here are large, comfortable and modern – and there are twelve more at the back, in chalet-like accommodation at the far end of the large garden. There’s also an especially appealing room in what amounts to a (cosy and luxurious) garden shed. The garden also accommodates an up-market restaurant. €120

Orangerie Kartuizerinnenstraat 10 ![]() 050 34 16 49,

050 34 16 49, ![]() hotelorangerie.be; map. In a former convent and one-time bakery, this classy, family-owned four-star hotel has twenty guest rooms, the pick of which are kitted out in an exuberant version of country-house style. The wood-panelled lounge oozes a relaxed and demure charm – as does the breakfast room - and a tunnel leads down to a canalside terrace. Great central location, too. €200

hotelorangerie.be; map. In a former convent and one-time bakery, this classy, family-owned four-star hotel has twenty guest rooms, the pick of which are kitted out in an exuberant version of country-house style. The wood-panelled lounge oozes a relaxed and demure charm – as does the breakfast room - and a tunnel leads down to a canalside terrace. Great central location, too. €200

Die Swaene Steenhouwersdijk 1 ![]() 050 34 27 98,

050 34 27 98, ![]() dieswaene.com; map. In a perfect location, beside a particularly pretty and peaceful section of canal close to the Burg, this long-established four-star hotel has thirty guest rooms decorated in an individual and rather sumptuous antique style. There’s also a heated pool and sauna. €120

dieswaene.com; map. In a perfect location, beside a particularly pretty and peaceful section of canal close to the Burg, this long-established four-star hotel has thirty guest rooms decorated in an individual and rather sumptuous antique style. There’s also a heated pool and sauna. €120

Ter Duinen Langerei 52

Ter Duinen Langerei 52 ![]() 050 33 04 37,

050 33 04 37, ![]() hotelterduinen.eu; map. Charming three-star hotel in a lovely part of the city, beside the Langerei canal, a 15min walk from the Markt. Occupies a beautifully maintained eighteenth-century villa, with period public areas and charming modern rooms. Superb breakfasts, too. €140

hotelterduinen.eu; map. Charming three-star hotel in a lovely part of the city, beside the Langerei canal, a 15min walk from the Markt. Occupies a beautifully maintained eighteenth-century villa, with period public areas and charming modern rooms. Superb breakfasts, too. €140

B&bs

Absoluut Verhulst Verbrand Nieuwland 1 ![]() 050 33 45 15,

050 33 45 15, ![]() b-bverhulst.com; map. Immaculate B&B with a handful of en-suite rooms in a tastefully modernized seventeenth-century house with its own walled garden. The Loft Suite is larger (and slightly more expensive) than the other rooms. €100

b-bverhulst.com; map. Immaculate B&B with a handful of en-suite rooms in a tastefully modernized seventeenth-century house with its own walled garden. The Loft Suite is larger (and slightly more expensive) than the other rooms. €100

Côté Canal Hertsbergestraat 8–10 ![]() 0475 45 77 07,

0475 45 77 07, ![]() bruges-bedandbreakfast.be; map. Deluxe affair in a pair of handsome – and handsomely restored – eighteenth-century houses, with four large guest rooms/suites kitted out in grand period style down to the huge, flowing drapes. Central location; the garden backs onto a canal. €165

bruges-bedandbreakfast.be; map. Deluxe affair in a pair of handsome – and handsomely restored – eighteenth-century houses, with four large guest rooms/suites kitted out in grand period style down to the huge, flowing drapes. Central location; the garden backs onto a canal. €165

Huis Koning Oude Zak 25 ![]() 0476 25 08 12,

0476 25 08 12, ![]() huiskoning.be; map. A plushly renovated B&B in a seventeenth-century, step-gable terraced house with a pleasant canalside garden. The four en-suite guest rooms are decorated in a fresh-feeling modern style and two have canal views. €120

huiskoning.be; map. A plushly renovated B&B in a seventeenth-century, step-gable terraced house with a pleasant canalside garden. The four en-suite guest rooms are decorated in a fresh-feeling modern style and two have canal views. €120

Number 11 Peerdenstraat 11 ![]() 050 33 06 75,

050 33 06 75, ![]() number11.be; map. In the heart of old Bruges, on a traffic-free side street, this first-rate B&B in an ancient terrace house has just four lavish guest rooms: all wooden floors, beamed ceilings and expensive wallpaper. Every comfort is laid on – and smashing breakfasts too. €150

number11.be; map. In the heart of old Bruges, on a traffic-free side street, this first-rate B&B in an ancient terrace house has just four lavish guest rooms: all wooden floors, beamed ceilings and expensive wallpaper. Every comfort is laid on – and smashing breakfasts too. €150

Sint-Niklaas B&B St-Niklaasstraat 18 ![]() 050 61 03 08,

050 61 03 08, ![]() sintnik.be; map. In a good-looking, three-storey, eighteenth-century townhouse on a side street near the Markt, this well-kept B&B has three modern, en-suite guest rooms. One has a lovely view of the Belfort. €145

sintnik.be; map. In a good-looking, three-storey, eighteenth-century townhouse on a side street near the Markt, this well-kept B&B has three modern, en-suite guest rooms. One has a lovely view of the Belfort. €145

Hostels

Bruges Europa Baron Ruzettelaan 143 ![]() 050 35 26 79,

050 35 26 79, ![]() jeugdherbergen.be/en; map. Big and looking like a school, this HI hostel is set in its own grounds, a (dreary) 2km south of the centre in the suburb of Assebroek. There are over 200 beds in a mixture of rooms from doubles through to twelve-bed dorms, most en suite. Breakfast is included in the price and there are security lockers, wi-fi, free parking, a bar and a lounge. City bus #2 from outside Bruges train station goes within 200m – ask the driver to let you off at the Wantestraat bus stop. Dorms €24, doubles €52

jeugdherbergen.be/en; map. Big and looking like a school, this HI hostel is set in its own grounds, a (dreary) 2km south of the centre in the suburb of Assebroek. There are over 200 beds in a mixture of rooms from doubles through to twelve-bed dorms, most en suite. Breakfast is included in the price and there are security lockers, wi-fi, free parking, a bar and a lounge. City bus #2 from outside Bruges train station goes within 200m – ask the driver to let you off at the Wantestraat bus stop. Dorms €24, doubles €52

St Christopher’s Bauhaus Langestraat 133–137 ![]() 050 34 10 93,

050 34 10 93, ![]() bauhaus.be; map. This lively, laid-back hostel, a 15min walk east of the Burg, has a boho air and offers a mishmash of rooms accommodating between two and sixteen bunks each, some with pod beds. Bike rental, lockers, a bar and café also available. Dorms €20, doubles €77

bauhaus.be; map. This lively, laid-back hostel, a 15min walk east of the Burg, has a boho air and offers a mishmash of rooms accommodating between two and sixteen bunks each, some with pod beds. Bike rental, lockers, a bar and café also available. Dorms €20, doubles €77

Eating