1

Growth and Jobs

Advocates of TTIP on both sides of the Atlantic are quick to paint the agreement as a massive contribution to ‘growth and jobs’. Eliminating remaining barriers to transatlantic trade and investment flows is said to be a boon to businesses, workers and consumers alike. US President Barack Obama has said that TTIP can help support ‘millions of good-paying American jobs’ (White House 2013a), while UK Prime Minister David Cameron has gone as far as to say that TTIP’s economic boost represents a ‘once-in-a-generation prize’ (cited in BBC News 2013). In the European context these claims have an added significance. With austerity de rigueur, TTIP is, in the words of the then EU Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht, ‘the cheapest stimulus package you can imagine’ (De Gucht 2013b).

Partly anticipating the controversy that was to engulf the negotiations, EU trade policymakers explicitly recognised this (as well as ‘setting global standards’; see chapter 2) as one of the key areas to push in their ‘information’ (read, public relations) campaign surrounding TTIP. In order to support this ‘growth and jobs’ story, the European Commission contracted a series of econometric studies that intended to show the economic benefits of the agreement. The most significant of these predicted gains for the EU of 0.48 per cent of GDP annually and for the US of 0.39 per cent, and has featured prominently in the discourse of European and US political figures. Given the obvious political importance attached to them, what are we to make of these claims?

In this chapter we interrogate the ‘growth and jobs’ narrative, focusing in particular on the use of these economic models. We suggest that these serve not only to exaggerate the benefits of TTIP but also deliberately to downplay its potential social costs. As the economic sociologist Jens Beckert (2013a, 2013b) puts it, modelling can be conceived of as an ‘exercise in managing fictional expectations’. The uncertainty inherent in modelling social outcomes, which are far more contingent than the calculations of economists, is shrouded from public view. In this vein, the models make unrealistic assumptions about the degree to which TTIP will be able to eliminate barriers to trade (especially given the, at best, mixed record of transatlantic cooperation so far), using biased data gleaned from surveys with business representatives. This, in turn, distracts from the potential costs of the agreement, which are far more difficult to quantify. This includes the social costs of macroeconomic adjustment (as jobs are likely to shift between industries) and the impact of potential deregulation on levels of social, environmental and public health protection. The models and the broader narrative they underpin are an important part of the wider ‘politics’ surrounding the negotiations, also shaping (as we will illustrate in subsequent chapters) the approach taken by negotiators to seeing regulation in narrow, economistic terms.

A way out of the crisis

In the EU, trade policy has become a central component of its response to the ongoing economic crisis. Facing reduced domestic demand and the realities of austerity, policymakers have argued two things. Firstly, that ‘economic recovery will … need to be consolidated by stronger links with the new global growth centres’ and, secondly, that ‘[b]oosting trade is one of the few means to bolster economic growth without drawing on severely constrained public finances’ (European Commission 2012: 4). Trade policy is being presented as one of the instruments to take Europe out of the crisis. In the words of the Commission again, it ‘has never been more important for the European Union’s economy’ (European Commission 2013e: 1, emphasis in the original).

EU leaders’ public pronouncements on TTIP represent the culmination of this particular rhetoric. De Gucht’s statement that the agreement represents ‘the cheapest stimulus package you can imagine’ is one of the most blatant in this respect, illustrative of a wider tendency to talk of TTIP as a way out of the crisis. The US, of course, has not plumped for austerity in the way that the Eurozone has, and therefore the crisis has not taken on as totemic a role in trade policy discourse. That said, the USTR has consistently emphasised the contribution of both TTIP and TPP to ‘growth and jobs’, a discourse also found at the presidential level in all State of the Union addresses since the start of the TTIP negotiations (White House 2013a, 2014, 2015).

As a result, the EU was not only the demandeur of (or party requesting) these negotiations, it has clearly accorded them somewhat more political importance than has the US. It has also largely taken the lead in selling TTIP to a potentially sceptical audience. As the Commission acknowledged in a leaked internal memo from November 2013, ‘[s]trong political communication will be essential to the success of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), both in terms of achieving EU negotiating objectives and of making sure that the agreement is eventually ratified.’ The aim should be ‘to define, at this early stage in the negotiations, the terms of the debate by communicating positively about what TTIP is about (i.e. economic gains and global leadership on trade issues)’ (European Commission 2013d).

We focus on the latter element of this narrative, ‘global leadership’, in chapter 2. Our attention here is centred on the idea that TTIP is about ‘economic gains’ for both parties. In order to bolster this claim, the Commission contracted a series of econometric studies, the most relevant of which was conducted by the London-based think tank the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR 2013). This in turn relies on estimates for non-tariff barriers (NTBs) to trade from an earlier study conducted by the Dutch management consultant firm ECORYS (2009a). The headline figures, quoted time after time by EU officials, but also occasionally by US leaders, are as follows. An ‘ambitious’ TTIP will generate extra gross domestic product (GDP) for the EU of €119bn annually, or €545 per average household, and €95bn ($120bn) for the US, or €655 ($830) per family.

There have also been a number of other recent modelling exercises of TTIP, which mostly rely on very similar modelling techniques to the CEPR and ECORYS studies (CEPII 2013; ECIPE 2010; Bertelsmann and IFO 2013). In these, TTIP is (in almost all instances) prophesied to have a positive impact on EU and US trade and GDP. But the magnitude of that positive impact varies wildly not only between studies (e.g., between a 0 per cent increase in EU/US GDP in one CEPII scenario and a boost of 4.82 per cent for the US in the Bertelsmann and IFO study) but also within studies. This is because the studies themselves contain various scenarios (as well as a baseline from which the changes in GDP and exports are calculated), from the very modest – eliminating only a small proportion of transatlantic barriers to trade – to the very ambitious – eliminating quite a substantial amount. In public, officials only ever quote the headline figure from the CEPR – which would result from the most ‘ambitious’ scenario – rather than the range of impacts, or the fact that these would materialise only by the year 2027. Moreover, it has been remarked that these headline figures amount only to ‘an extra cup of coffee per person per week’ (Moody 2014), hardly warranting the bombastic rhetoric used. This brings us to the politics of economic modelling.

Economic modelling and the ‘management of fictional expectations’

In what way is economic modelling a political tool? While much has been said about economic discourses in political economy, far less has been said (at least by political scientists) about another powerful form of economic narrative, the ubiquitous use of economic modelling and forecasting. This may be because those working in the field of political economy have sometimes shied away from engaging with quantification and the specific insights of economists (Blyth 2009). This is a real shame, as there is a clear politics behind the use of economic forecasting, which purports to be an exercise in ‘objective’ and reliable science that is anything but.

Both the EU and the US have a history of (mis)using economic modelling. One of the EU’s crowning achievements, the Single Market that eliminated numerous existing NTBs between European economies, is a case in point. Of the most influential Commission papers to come out at the time, the so-called Cecchini report estimated GDP gains from completing the Single Market Programme of between 4.25 and 6.5 per cent (European Commission 1988: 10). This turned out to be wildly exaggerated. Even the Commission’s own 2007 Single Market Review estimated the gains to be around half of the lower bound of the Cecchini estimates, at 2.15 per cent (European Commission 2007a: 3). Given such a margin of error in calculating the benefits of the Single Market, what is the value to the EU of the prophesied 0.48 per cent GDP boost from TTIP?

Similarly stark is the use of economic modelling to sell the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to a sceptical US audience. While US presidential candidate Ross Perot capitalised on much apprehension about outsourcing and job losses by referring to the ‘giant sucking sound’ of US jobs being displaced to Mexico, the US government drew on a wealth of econometric studies that all seemed to confirm NAFTA’s job-creating and growth-boosting credentials. In some cases the prophesied growth increase was as much as 10.6, 2.1 and 13.1 per cent, for the Canadian, US and Mexican economies respectively (Stanford 2003: 31). These overoptimistic models have since been widely derided, given the finding that there has been ‘no visible impact of continental trade liberalization on overall economic growth rates in the three NAFTA member economies’ (ibid.: 37). This may explain, at least in part, why US political leaders have been more cautious in their talk about TTIP and less wont to draw on specific figures than their European counterparts. Indeed, in his 2015 State of the Union address, President Obama was ‘to admit that past trade deals haven’t always lived up to the hype’ (White House 2015).

Managing fictional expectations

Our hope here, however, is to go beyond the aphorism attributed to Benjamin Disraeli that there are ‘lies, damned lies and statistics’ and develop a more sophisticated critique of econometric modelling. In order to do so, we draw on the work of the economic sociologist Jens Beckert (2013a, 2013b) and, more specifically, his idea of ‘fictional expectations’. Beckert sees the social world as inherently contingent and the future as fundamentally uncertain. There are far too many intervening factors for us accurately to predict how events will unfold. The extreme example of this is Nassim Taleb’s (2007) concept of the ‘black swan’, an event with dramatic consequences so rare and unpredictable (much like the discovery of hitherto unknown black swans by European explorers in Australia) that its occurrence cannot be inferred from past experience (cue reference to the global financial crisis of 2008). This assumption of fundamental uncertainty distinguishes such work from that of mainstream, neoclassical economists (as well as other rationalist social scientists) who assume that the economy (and society) operates according to well-defined and regular factors that can accurately and reliably be modelled and extended into the future.

If the social and economic future is unknowable, how then do we get by in our social lives? If you are a business owner, how are you able to plan accounts for the year – or order stock on a weekly basis? Beckert argues that we make do with so-called fictional expectations. These are ‘imaginaries of future situations that provide orientation in decision-making despite the uncertainty inherent in the situation’ (Beckert 2013a: 222, emphasis in the original). There is an important analogy here to literary texts in that, in both cases, we are willing to suspend our disbelief, although for very different reasons. In the former this is the entire purpose of a good yarn: what point is there to naysay an unbelievable plotline when this makes for an entertaining story? In the latter, these expectations are essentially a way of muddling through an inherently uncertain social world. In this vein they ‘represent future events as if they were true, making actors capable of acting purposefully … even though this future is indeed unknown, unpredictable, and therefore only pretended in the fictional expectations.’ Moreover, such expectations are ‘necessarily wrong because the future cannot be foreseen’ (ibid.: 226, emphasis in the original).

Of course, not all ‘fictional expectations’ are the same: a small shop owner ordering groceries on the basis of anticipated sales is not in the same boat as a Wall Street financier speculating on the housing market. While the former’s activities would be considered quite normal and routinised – indeed, Beckert sees such practices as necessary to sustain capitalism and markets – the expectations of participants in financial markets are seen as an important determinant of their fragility. Ultimately, as political scientists concerning ourselves with the concept of power, we are interested in the idea that ‘[a]ctors have different interests regarding prevailing expectations and will therefore try to influence them’ (Beckert 2013b: 326). This ‘management of fictional expectations’ is precisely what we would argue is going on in the case of the economic modelling surrounding TTIP.

The politics of economic modelling

Of the economic studies on TTIP, almost all (save the one produced by Bertelsmann and IFO) rely on so-called computable general equilibrium (CGE) models. These models simplify the eminently complex social world out there by reducing it to a number of key variables in order to account for the economic impact of particular policy decisions. For example, they might model the impact that an increase in taxation has on consumption, or (as in this case) whether trade liberalisation leads to increased growth. Within this ‘model world’ (Watson 2014) individuals are what is called rational utility-maximisers – that is to say, they are always able (and willing) to logically determine their best interests and act upon them. Most importantly, and as the term general equilibrium gives away, CGE follows standard economic theory1 in assuming that the natural state of economic markets is to be in balance. All supply finds its own demand in perfectly efficient and competitive markets (although allowance is sometimes made for non-competitive market structures, as in the CEPR TTIP model). This means that, for every market, all that is produced is consumed and there is no unemployment, as all supply for labour is met with appropriate demand. The whole point of modelling is to assume away the complexity of the economy; the persistence of unemployment, for example, is a clear indicator that all is not well with the world of general equilibrium.2 All the modeller cares about is generating a simplified equation that captures the relationship in which they are interested (e.g., between taxation and consumption, trade liberalisation and GDP) and which is ‘computable’, allowing them to plug in data and run a regression that generates concrete figures. In this vein, CGE modelling has grown to become one of the standard forms of modelling the economic impact of policy decisions since it was originally developed in the 1960s (Dixon and Rimmer 2010), especially in the field of trade liberalisation, where the figures used to sell NAFTA were some of the first prominent instances of the use of such models.

In what ways can we speak of a ‘management of fictional expectations’ when talking about CGE modelling? On the one hand, these are clearly ‘fictional expectations’ insofar as they produce predictions about the future state of the economy that are intended to guide future action. What is particularly striking, however, is the fact that the forecasts produced are incredibly unreliable. One experienced modeller, Clive George (an architect of trade sustainability impact assessment [IA] in the EU), argues that ‘[i]n some cases the uncertainty is bigger than the number [generated by such models] itself, such that a number predicted to be positive could easily be negative’ (George 2010: 25). The examples we cited above of the Cecchini report and the modelling around NAFTA are cases in point. Beckert’s notion that such expectations must by their very nature be wrong because the future cannot be foreseen is thus doubly true, both because of the inherent problem of uncertainty and because the models are unable to generate reasonable forecasts.

But what of the ‘management’ of these expectations? In what ways can we speak of a deliberate strategy to ‘influence’ them? We would argue that CGE models do so in at least three ways. First of all, they contain a series of assumptions which are not only unrealistic – undermining their reliability, as highlighted earlier – but which also privilege a particular view of the world (Ackerman 2004). Beyond assuming general equilibrium, the most Pareto efficient3 and therefore desirable outcome from the perspective of economists, such models appear to be agnostic on other questions, such as the inequalities that may result. As two prominent modellers put it, ‘the decisions how to resolve potential trade-offs [between equity and efficiency] must be taken on the basis of societal values and political decisions’ (Böhringer and Löschel 2006: 50). However, this agnosticism is anything but. Values are a lot fuzzier than numbers, which means they appear far less objective than the ‘realities’ and ‘imperatives’ of markets (the domain of the economic modeller). As Fioramonti (2014: 9) puts it, ‘[m]arkets are more malleable to measurement’ than ‘social relations and the natural world’. The land value of a national park may be relatively easy to determine, as may tourist revenues associated with it, but it is far harder to quantify what many may call its ‘intrinsic value’ as a nature reserve (ibid.: 104–43).

More blatant than this broad, implicit bias in CGE models is the power the researcher has to shape the results of their modelling. Just changing the data used, the variables computed or the values on the coefficients in the regression equation can have a massive effect on the results. As even The Economist (2006, cited in Scrieciu 2007: 681), a newspaper known for its advocacy of the free market, put it in the case of studies examining the relationship between trade, productivity and growth: ‘[i]f the [CGE] modeller believes that trade raises productivity and growth … then the model’s results will mechanically confirm this.’

Although they have come under increasing fire from economists, CGE models are powerful political tools for a third reason. They are essentially ‘black boxes’ (Piermantini and Teh 2005: 10), often impenetrable to most lay readers unfamiliar with general equilibrium theory. This serves to shield their biases and lack of reliability from public view. We are willing to ‘suspend our disbelief’ because we simply have no means of doing otherwise. It is no wonder that the heterodox economist Ha-Joong Chang (2014) has called on the public to become more economically literate! In this spirit, it is time to look at how CGE modelling has been used to shield TTIP from criticism, starting with the exaggerated benefits of the agreement. Before we turn to this, however, it is important to stress that we are not seeking to engage in a detailed, technical critique of the econometric modelling used for TTIP or to generate our own figures. Rather, what we are doing is pointing to the inherently political nature of modelling.

Modelling TTIP

How have the modellers come up with TTIP ‘growth and jobs’ figures? Here we focus specifically on the CEPR model, as this has had the greatest prominence. It was not only announced with some fanfare by a Commission press release in March 2013 (European Commission 2013f) but was also the basis for the EU’s own ‘Impact Assessment’ of TTIP (European Commission 2013a). These are also the figures that are most likely to be quoted by advocates of TTIP. But, while many of the assumptions we drill into here are specific to the CEPR (2013) model, the broader arguments are more widely applicable. Most of the studies of TTIP’s economic impact use CGE modelling. They therefore make very similar simplifying assumptions, use very similar trade data, and are open to very similar biases as the CEPR report.

First, we must examine what sort of assumptions the modellers have built into their study. The model features a number of different scenarios – or assumed outcomes from EU–US negotiations – for which different results are generated. The first of these is a so-called baseline scenario, which assumes that no trade deal is signed. All the other scenarios are assessed against this benchmark and include ones that assess the effect of only removing tariffs or only eliminating barriers to trade in services or to government procurement (the purchasing of goods and services by public bodies). The variety of scenarios in this (and indeed other models) explains the large variation in the results we noted earlier.

At the upper end of the CEPR estimates is the most important scenario – the only one habitually quoted by supporters of the agreement. This assumes that a ‘comprehensive’ and ‘ambitious’ FTA will be signed between the EU and the US, covering all manner of barriers to trade. More specifically, it assumes that TTIP will eliminate all tariffs on goods traded between the EU and the US and remove 25 per cent of all NTBs restricting trade in goods and services. This 25 per cent figure includes eliminating 50 per cent of barriers in the field of government procurement. The study also makes an allowance for ‘spillover effects’; both exporters in the EU/US and those in third countries might benefit from fewer transatlantic barriers to trade and from TTIP’s assumed effect in terms of leading the rest of the world to align its standards with the new ‘transatlantic marketplace’. Making these assumptions leads the modellers to the following (in)famous results: extra GDP per annum of 0.48 per cent in the case of the EU and 0.39 per cent in the case of the US, or €119 billion for the EU and €95 billion for the US (CEPR 2013: 2).

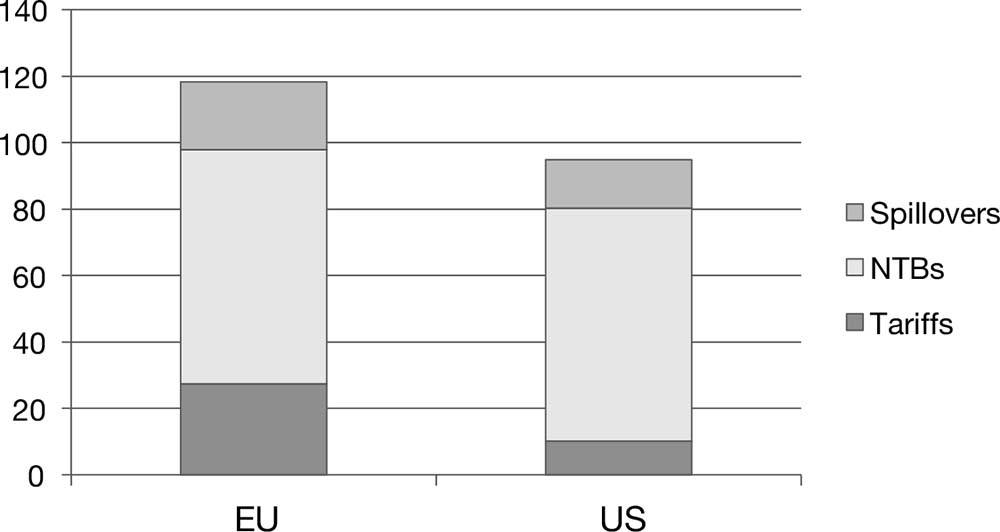

Are these assumptions reasonable? Will TTIP deliver all that is being promised? As figure 1.1 clearly illustrates, a vast majority of the estimated gains for both the EU and the US ultimately comes from the hypothesised reductions in NTBs and not from tariff elimination. In the case of the EU, a whole 59 per cent of the GDP gains come from regulatory alignment (and only 23 per cent from eliminating tariffs), while for the US this figure is a whopping 74 per cent (with only 11 per cent of the gains coming from eliminating tariffs)! How hard could it possibly be to eliminate 25 per cent of existing regulatory barriers to trade? Surely a quarter of these is not that much to ask negotiators to tackle?

Figure 1.1 Breaking down the gains from trade liberalisation in TTIP, € billions

Source: Adapted from De Ville and Siles-Brügge (2014b: 13).

Overblowing the benefits

Our argument is that this is a far more heroic assumption than the modellers are implying. For one, only 50 per cent of NTBs between the EU and the US are even considered ‘actionable’ within the data used by the study. In other words, only half are the direct result of policy decisions that can be addressed through a trade agreement such as TTIP (CEPR 2013: 27). Other NTBs include such things as consumer tastes, which are beyond the scope of a trade agreement. Thus, for example, TTIP could theoretically remove regulatory barriers to the selling of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in Europe, but it could not possibly directly shape European consumers’ oft-remarked suspicion of such products. So 25 per cent of all NTBs turns into 50 per cent of ‘actionable’ NTBs, an altogether more significant proposition. Moreover, the definition of what is ‘actionable’ is also pretty generous, insofar as it includes any measure that is theoretically within the realm of policy to address. As we suggested in the introduction to this book, the history of EU–US transatlantic regulatory cooperation has been plagued with difficulties; even modest attempts at regulatory alignment through mutual recognition agreements were blocked because US federal regulators were keen to preserve their ability to regulate. There have also been a number of high-profile transatlantic trade disputes over differences in the approach of the EU to food safety in such areas as hormone-treated beef or GMOs (Pollack and Shaffer 2009).

The prospects for bridging such differences are relatively slim, especially if we consider the two main sectors expected to gain from the agreement. These are automobiles and chemicals, together accounting for 59 per cent of the expected increase in exports for the EU from TTIP (and 54 per cent in the case of the US; authors’ calculation based on data from CEPR 2013: 64, 66). In the case of chemicals, much has been made of the EU’s ‘precautionary approach’ to regulation under the Regulation on the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) – where the burden of proof lies on manufacturers to show that their chemicals are safe before they are authorised – and the US’s laxer ‘science-based’ approach, which puts the burden on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to show that chemicals are noxious (Vogel 2012: 154–78). The EU and the US are so far apart on this issue that the Commission itself has been forced to admit at the start of the negotiations that ‘neither full harmonisation [the creation of a common EU/US standard] nor mutual recognition [where both sides accept each other’s standards] seems feasible on the basis of the existing framework legislations in the US and EU: [these] are too different with regard to some fundamental principles’ (European Commission 2013g: 9).

But what about automobiles? These are the poster child of advocates of TTIP insofar as it is generally acknowledged that car and other motor vehicle safety standards are broadly compatible across the Atlantic (ECORYS 2009a: 44, 46–7). Few would quibble about the exact positioning of headlamps, the colour of indicator lights, or some of the more technical specifications for seat belts. But, while regulatory outcomes might not differ greatly in this sector, regulatory alignment faces the prospect of multiple jurisdictions in the US (due to variations in state emissions policies) – as well as important differences in the way in which conformity with such standards is assessed. As the Commission was also forced to admit in its position paper for the negotiations, mutual recognition of technical requirements ‘could not be extended to conformity assessment, in view of the wide divergence between conformity assessment systems (prior type approval in the EU, in accordance with the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe [UNECE] system, and self-certification with market surveillance in the US)’ (European Commission 2014c: 2, emphasis added). Moreover, the view that regulatory convergence for the automobile sector is somehow ‘easy’ to achieve – what often gets referred to as the ‘low-hanging fruit’ of the negotiations (Lester and Barbee 2014) – ignores the zeal with which the powerful, independent US regulators have clung on to their independence, as the past experience of the EU–US regulatory cooperation in the 1990s shows, where the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) blocked the implementation of a series of MRAs (House of Lords 2013: 3–4).

Even if an agreement brings a breakthrough in one or the other sector, the gains from TTIP are hardly assured, as the modelling assumes important interlinkages between sectors. In other words, it assumes regulatory alignment across all sectors; in an interconnected economy based on various supply chains, the effects of dealing with regulatory barriers in one sector clearly cut across others. For example, reducing barriers for chemical producers will have an important knock-on effect for industrial users of chemicals as well as any of their other business customers or end users. Thus, figures taken from the ECORYS 2009 study – which provides the figures on NTBs for the EU and the US for the CEPR study – show that adding up liberalisation in each sector produces only roughly a quarter of the gains for the EU and a third for the US when compared to liberalisation across the board (ECORYS 2009a: xxi–xxii). If we liken TTIP to an attempt at toppling a chain of dominoes, taking out any one tile (or sector) is likely to affect the end result drastically.

To top it all, there is also evidence of bias in the NTB figures themselves, which were produced with the help of a number of EU and US business representatives with a strong interest in the conclusion of negotiations (see chapter 3). They derive from a combination of discussions with forty sectoral experts with close ties to business, literature reviews – carried out by these sectoral experts ‘supported by’ ECORYS and a number of transatlantic business groups – as well as a ‘business survey’ with around 5,500 participants (ECORYS 2009a: 9–10). As the authors of one critical study have noted, such business actors (and those close to them) have a clear interest in exaggerating both the cost of NTBs and the degree to which TTIP might be able to address them (in the jargon, their ‘actionability’) (Raza et al. 2014). On the first point, the literature review, business survey and sectoral experts estimated that NTBs added, respectively, around 10, 7 and 8 per cent to transatlantic trade costs (ECORYS 2009a: 9), when other studies have suggested a much lower figure, in the region of 3 per cent (Raza et al. 2014: viii).4 On the issue of whether these NTBs can be addressed through policy, the verdict is similar: the business representatives and others consulted in preparing the data may well ‘exhibit a tendency to overestimate actionability. Thus, the determination of actionability is basically a more or less sophisticated guess of a group of persons with vested interests’ in talking up the potential of TTIP (ibid.: 21).

It is important to stress at this point that we are also trying to avoid falling into the same trap of making steadfast predictions as the econometric studies. Even if TTIP leads to significant liberalisation, predicting this at the start with problematic models is a clear example of managing fictional expectations (which are ‘necessarily wrong’ because the future cannot be foretold), especially so given the past history of limited integration, the limitations to liberalisation in TTIP acknowledged by the Commission itself, and the clear bias in the NTB figures.

Downplaying the potential costs

The ‘management of fictional expectations’, however, goes beyond the specific assumptions of the studies or their use of problematic data. Rather, talking of the ‘huge’ (and costless) boost given to EU and US growth and jobs allows policymakers to talk down some of the potential costs of the agreement. It privileges what can (in a very flawed way) be measured – future economic gains – over what is more difficult to quantify – the broader social and/or environmental impact of the agreement. As is argued in what follows, these include the broader economic costs of adjusting to freer trade and the potential deregulation that might come from aligning standards. This is the great fear expressed by opponents to the deal (see chapter 4).

‘Macroeconomic adjustment costs’ (to use their more technical name) may include such things as losses in tariff revenue, destabilising changes in the trade balance, and the ‘displacement’ of workers from uncompetitive industries (Raza et al. 2014: v–vi). Of course, statistics can be mustered to account for such developments: the CEPR study itself comes up with an estimate of between 400,000 and 1.1 million jobs being ‘displaced’ (workers being shifted from one job to another; ibid.: iv). But the assumption, following general equilibrium theory, is that this is a mere ‘displacement’ of workers from one sector to another; to rephrase a much derided line often (erroneously) attributed to the then British Conservative cabinet minister Norman Tebbit, workers will simply ‘get on their bikes’ and find new work. Overall, there will be no increase in unemployment. This downplays not only the unequal distribution of gains from TTIP – as with any trade agreement, a number of sectors in both the EU and the US stand to lose from an agreement liberalising trade – but also the wider social costs of unemployment. The assumption is that the economy will be able unproblematically to adjust to external competitive pressures, which is not entirely consistent with the experience of several deindustrialised regions in Europe and the US (Northern England and the ‘Rustbelt’ spring to mind). This point has not been lost on high-profile critics of TTIP and TPP in the US (such as Joseph Stiglitz, Robert Reich, Clyde Prestowitz or Paul Krugman) in the context of ongoing debate on renewing ‘fast-track’ negotiating authority (Krugman 2014; Stiglitz 2014; Reich 2015; Prestowitz 2015).

Even more significant, given TTIP’s focus on regulation, is the potential deregulatory impact the agreement may have. While we discuss this in more depth in chapter 3, here it is important to underscore how the modelling deliberately downplays the impact of such a development. As noted by other critics, ‘the elimination of NT[B]s will result in a potential welfare loss to society, in so far as this elimination threatens public policy goals (e.g. consumer safety, public health, environmental safety)’ (Raza et al. 2014: vi). It is thus somewhat disingenuous for the modellers to argue that their studies do ‘not judge whether a specific NT[B] is right or wrong or whether one system of regulation is better than the other’. Focusing on the objective of ‘identifying divergences in regulatory systems that cause additional costs or limit market access for foreign firms’ (ECORYS 2009a: xxxv) can hardly be called a neutral exercise. It paints these ‘divergences’ as mere ‘barriers’ to trade to be removed – rather than potentially serving a legitimate social purpose (on how the benefits of regulation are downplayed; see Myant and O’Brien 2015). Moreover, the future deregulatory impact of TTIP is not only very difficult to measure but also fundamentally uncertain, which makes it difficult to counter the ‘hard’ figures of the modeller (which are of course anything but objective).

In this vein, both the modellers and the European Commission have sought to downplay the uncertainty underpinning the CEPR study. Instead, this is presented as eminently reasonable and even cautious in its conclusions. The modellers characterise their assumptions regarding the degree of NTB liberalisation as ‘relatively modest’, while also emphasising the advanced nature of their CGE modelling (CEPR 2013: 21–2, 27). The Commission, for its part, has stated that this study uses a ‘state of the art’ model with assumptions ‘as reasonable as possible to make it as close to the real world as possible’. The model, moreover, also lies ‘at the mid-range of most other studies carried out on TTIP’, with ‘[t]he Commission believ[ing] in a conservative approach to analysis of policy changes’ (European Commission 2013h: 2–3). No ‘health warnings’ are attached, as doing so might undermine the model’s usefulness as an exercise in ‘managing fictional expectations’.

Contesting economic modelling

Numbers have become a key battleground in the fight over TTIP. Seeking to shape the debate on the agreement ‘on its own terms’, the Commission sponsored a study that seemed to show ‘significant’ economic gains from ‘cutting red tape’ across the Atlantic – up to €545 per family of four in the EU (or $830 for a family in the US). Since its publication, however, there has been growing scepticism, especially as the methodology is increasingly said to be ‘based on unrealistic and flawed assumptions’ (Raza et al. 2014: vii). A 2014 European Court of Auditors report on the Commission’s management of preferential trade agreements found that it had ‘not appropriately assessed all the[ir] economic effects’. It also included an entire annex on the ‘Limitations of the CGE model’ the Commission had been so wont to use in its assessments of trade agreements (European Court of Auditors 2014: 8, 45). The irony behind all of this is of course that a CGE model is being used to justify a trade agreement that is supposed to lift the EU out of the crisis, when a permutation of such general equilibrium models (more specifically, dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modelling) completely failed to predict the advent of the 2007–8 Financial Crisis (Watson 2014).

What is even more interesting from our perspective is that the presentation of this modelling by the Commission has been widely criticised by civil society groups. In a letter from non-governmental organisations (NGOs), the Commission has been accused of ‘exaggeration’ (for citing only the upper econometric estimates), providing insufficient information on ‘time scale’ (for not citing that the gains will materialise only by 2027) and of ‘us[ing] obfuscating language … that is very difficult to understand for lay persons’ (BEUC and Friends of the Earth Europe 2014: 1–2) – all features of the management of fictional expectations we described above. The danger is that, having caught on to this, some have sought to fight fire with fire, seeking to quantify the negative impact of the agreement. One study – prominently invoked by critical actors and making use of an alternative, Keynesian methodology that does not assume full employment (the UN Global Policy Model) – speaks of 600,000 lost jobs across the EU and GDP losses of 0.07, 0.29 and 0.48 per cent in the UK, Germany and France respectively (Capaldo 2014). There are also attempts (ongoing at the time of writing) to measure the deregulatory impact of TTIP.5 But, much as the gains from TTIP are impossible to predict, we must be intellectually honest and accept that its potential costs are ‘subject to considerable uncertainty’, especially while the talks are still taking place (Raza et al.2014: iv). Even once the negotiations on TTIP are concluded, we would contest the notion that you can simply reduce the impact of the agreement on social, environmental and public health regulation to a series of economic statistics. This is falling into the trap of accepting the broader normative biases of econometric modelling.

Moreover, while there may be increased contestation of the numbers behind TTIP that feeds into a critical narrative about the negotiations (see chapter 4), advocates have fought back. While they have toned down the rhetoric to speak about ‘growth and jobs’ more generally (without necessarily invoking specific figures), there has also been a push to emphasise the benefits of TTIP in terms of ‘cutting red tape’. This is said to benefit not just large, multinational exporters but also small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In the words of the USTR Michael Froman (2015), ‘[m]any people assume exporting is a game that’s limited to big businesses, but in reality, 98% of our 300,000 exporters are small businesses.’ Both he and his counterpart, the European Trade Commissioner, have been keen to emphasise the potential of TTIP for such small businesses, frequently citing examples of specific SMEs that would benefit from a freer transatlantic marketplace (Froman 2014; Malmström 2015a).6 Meanwhile various business organisations have produced reports based on case studies of various SMEs that are said to gain from a reduced transatlantic regulatory burden (e.g., British American Business 2015).

It is thus clear that numbers and claims of economic gains remain a key arena in the battle for TTIP. Another is the argument that the agreement will allow the EU and the US to shape the face of global economic governance for years to come. We discuss this next.