Media Library

CHAPTER 3 Media Library

PREMIUM VIDEO

SAGE CORE CONCEPTS

SAGE Core Concepts 3.1: Race and Ethnicity

AP NEWS CLIPS

AP News Clips 3.2: Ferguson Demonstrations

AP News Clips 3.3: US Immigration Protest

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

3.1 Describe the difference between race and ethnic groups.

3.2 Identify the different types of institutional discrimination.

3.3 Summarize how the sociological perspectives explain problems related to race and ethnicity.

3.4 Describe the impact of immigrant workers on the U.S. labor force.

3.5 Explain how the college experience increases racial/ethnic diversity awareness.

Days after White nationalists and counter protestors clashed on their campus, University of Virginia (UVA) students gathered to express their solidarity against hate and racism. Three people died, and more than 30 individuals were injured in a series of violent clashes over the August 2017 weekend. UVA students assembled under a banner that read, “Our mission therefore is to confront ignorance with knowledge, bigotry with tolerance, and isolation with the outstretched hand of generosity. Racism can, will and must be defeated” (Kelly 2017). The university’s rector Frank Conner (2017) acknowledged, “We all need to transform our anger at the actions of this past weekend so as to rededicate our energy, our talents, and our hearts to our institutional purpose of developing citizen leaders in all fields of endeavor to evolve into a more perfect union. If we are to succeed in that purpose, we must be honest about the issues facing our society.”

The United States is a diverse racial and ethnic society. The U.S. Census Bureau (2012b) predicts that by 2043, non-Hispanic Whites will no longer make up the majority of the U.S. population. Acting Census Bureau director Thomas L. Mesenbourg (U.S. Census Bureau 2012b) described the United States as a “plurality nation, where the non-Hispanic white population remains the largest single group, but no group is in the majority.” The minority population (Hispanic, Black, Asian, American Indians, and Alaska Natives) is projected to account for 57% of the population by 2060 (U.S. Census Bureau 2012b).

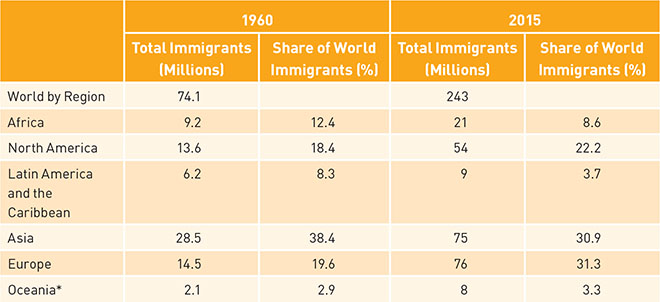

Adding to the diversity of our population are increasing numbers of immigrants, their migration to the United States and throughout the world spurred by the global economy. In 2013, 69% of international migrants lived in high-income countries (nations with an average per capita income of $12,616 or more, such as the United States and Germany) compared with 57% in 1990 (Connor, Cohn, and Gonzalez-Barrera 2013). Population mobility since the middle of the 20th century has been characterized by unprecedented volume, speed, and geographical range (Collin and Lee 2003). At the end of 2015, 243 million people, lived in a country other than their birth country (United Nations 2016). As Zygmunt Bauman (2000) said, “the world is on the move” (p. 77). Regionally, Europe has the largest number of international migrants (about 76 million), followed by Asia (75 million) and North America (54 million) (United Nations 2016) (refer to Table 3.1).

Racial divisions remain a defining feature of our social lives (Brown 2013). Complete racial equality and harmony remain elusive in the United States. In this chapter, we explore how one’s racial and ethnic status serves as a basis of inequality. Like social class, race or ethnicity alters one’s life chances, and members of particular groups experience an increased likelihood of experiencing particular social problems. We begin first with understanding how race and ethnicity are defined.

p.52

TABLE 3.1 ■ Regional Distribution of International Migrants, 1960 and 2015

Source: United Nations 2009, 2016.

*Oceania includes Micronesia, Melanesia, Polynesia, Australia, and New Zealand.

DEFINING RACE AND ETHNICITY

The term race has been applied broadly to groups with similar physical features (the White race), religion (the Jewish race), or the entire human species (the human race) (Marger 2002). However, generations of migration, intermarriage, and adaptations to different physical environments have produced a mixture of races. There is no such thing as a “pure” race.

© David McNew/Getty Images

In fiscal year 2016, more than 750,000 people were naturalized. To be eligible for citizenship, immigrants must meet requirements set by immigration laws. Eligibility includes age (at least 18 years of age or older) and residency (at least 3 or 5 years as a permanent resident), along with other requirements.

Social scientists reject the biological notions of race, instead favoring an approach that treats race as a social construct. In Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s, Michael Omi and Howard Winant (1994) explained how race is a “concept which signifies and symbolizes social conflicts and interests by referring to different types of human bodies” (p. 54). Instead of thinking of race as something “objective,” the authors argued that we can imagine race as an “illusion,” a subjective social, political, and cultural construct. In the United States, race tends to be a bipolar construct—White versus non-White. According to the authors, “the meaning of race is defined and contested throughout society, in both collective action and personal practice. In the process, racial categories themselves are formed, transformed, destroyed, and reformed” (Omi and Winant 1994:21). Robert Redfield (1958) said it simply: “Race is, so to speak, a human invention” (p. 67).

Race may be a social construction, but that does not make race any less powerful and controlling (Myers 2005). Omi and Winant (1994) argued that although particular stereotypes and meanings can change, “the presence of a system of racial meaning and stereotypes, of racial ideology, seems to be a permanent feature of U.S. culture” (p. 63).

p.53

Ethnic groups are set off to some degree from other groups by displaying a unique set of cultural traits, such as their language, religion, or diet. Members of an ethnic group perceive themselves as members of an ethnic community, sharing common historical roots and experiences. All of us, to one extent or another, have an ethnic identity. Increasingly, the terms race and ethnicity are presented as a single construct pointing to how both terms are being conflated (Budrys 2003).

Martin Marger (2002) explained how ethnicity serves as a basis of social ranking, ranking a person according to the status of his or her ethnic group. Although class and ethnicity are separate dimensions of stratification, they are closely related: “In virtually all multiethnic societies, people’s ethnic classification becomes an important factor in the distribution of societal rewards and hence, their economic and political class positions. The ethnic and class hierarchies are largely parallel and interwoven” (Marger 2002:286).

The federal definition of ethnicity is based on the Office of Management and Budget’s 1977 guideline (U.S. Census Bureau 2005), which defines ethnicity in terms of Hispanic/non-Hispanic status, contrary to the conventional social scientific definition as presented in the previous paragraphs. The U.S. Census treats Hispanic origin and race as separate and distinct concepts; as a result, Hispanics may be of any race.

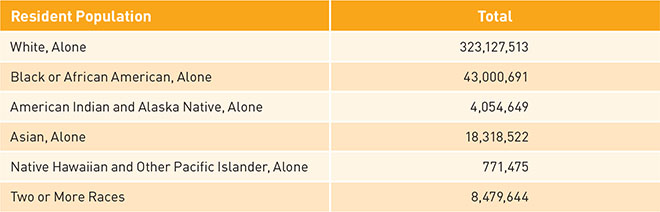

Since 2002, Hispanic Americans have been the nation’s largest ethnic minority group. The U.S. Census Bureau includes in this category women and men who are Mexican, Central and South American, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and other Hispanic. The 2016 ethnic and racial composition estimates of the United States are presented in Table 3.2. In 2012, the U.S. Census reported for the first time that minority (non-White) births were the majority—50.4% of children younger than age 1 year were Hispanic, Black, Asian, or of mixed race. Non-Hispanic Whites accounted for 49.6% of all births in a 12-month period (U.S. Census Bureau 2012a). Commenting on the report, demographer William Frey (quoted in Tavernise 2012:A1) said, “This is an important tipping point . . . [a] transformation from a mostly white baby boomer culture to a more globalized multiethnic country that we’re becoming.” By 2020, more than half of the nation’s children will be part of a minority race or ethnic group (Colby and Ortman 2015).

TABLE 3.2 ■ Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Race, 2016

Source: U.S. Census Bureau 2016a.

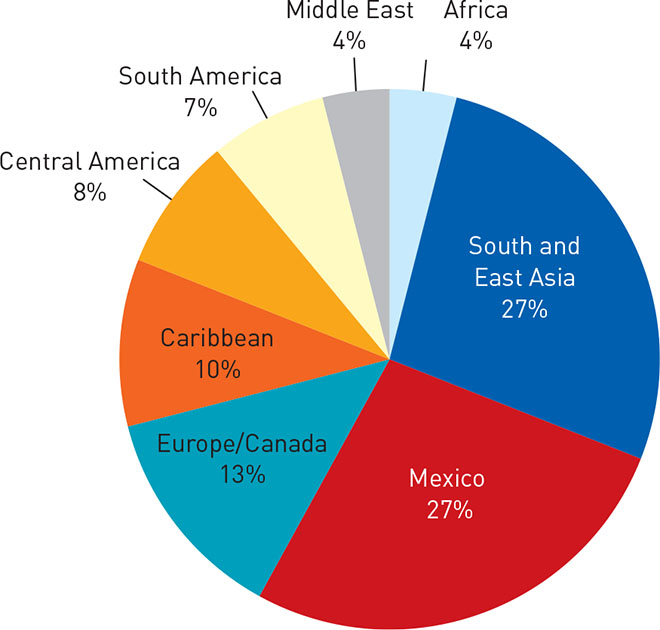

The U.S. Census distinguishes between native and foreign-born residents. Native refers to anyone born in the United States or a U.S. island area such as Puerto Rico or the Northern Mariana Islands or born abroad of a U.S. citizen parent; foreign born refers to anyone who is not a U.S. citizen at birth. Elizabeth Grieco (2010) wrote, “The foreign born, through their own diverse origins, will contribute to the racial and ethnic diversity of the United States. How they translate their own backgrounds and report their adopted identities have important implications for the nation’s racial and ethnic composition.” In 2015, among the 43.2 million foreign born in the United States, most were from South and East Asia and from Mexico (both 27%, as displayed in Figure 3.1).

p.54

FIGURE 3.1 ■ Region of Birth for Immigrants in the U.S. (Percentage by World Region), 2017

Source: Lopez and Bialik 2017.

What Does It Mean to Me?

In 2017, the U.S. Department of Justice requested the addition of a new citizenship question on the 2020 Census. The Department of Justice maintained that the question was necessary to better enforce the Voting Rights Act. The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights and 170 civil and human rights groups (2018) wrote against the request, saying, “Adding this question would jeopardize the accuracy of the 2020 Census in every state and every community by deterring many people from responding.” Despite these expressed concerns, in March 2018, the U.S. Department of Commerce announced the question would be included in the census. Explain how the citizenship question would risk the accuracy of the 2020 Census.

Refugees are defined by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1980 as “aliens outside the United States who are unable or unwilling to return to his/her country of origin for persecution or fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” Data on the number of admitted refugees are collected annually by the U.S. Department of State. In 2017, 53,716 persons were admitted as refugees, the majority from Near East/South Asia (U.S. Department of State 2017).

Tracy Ore (2003) acknowledged that externally created labels for some groups are not always accepted by those viewed as belonging to a particular group. For example, those of Latin American descent may not consider themselves to be “Hispanic.” In this text, I’ve adopted Ore’s practice regarding which racial and ethnic terms are used. In my own material, I use Latino to refer to those of Latin American descent, and Black and African American interchangeably. However, original terms used by authors or researchers (e.g., Hispanic as used by the U.S. Census Bureau) are not altered.

p.55

What Does It Mean to Me?

You may not be able to tell from my last name (Leon-Guerrero), but I consider my ethnic identity to be Japanese. I am Japanese not only because of my Japanese mother but also because of the Japanese traditions I practice, the Japanese words I use, and even the Japanese foods I like to eat. Do you have an ethnic identity? If you do, how do you maintain it?

PATTERNS OF RACIAL AND ETHNIC INTEGRATION

Sociologists explain that ethnocentrism is the belief that one’s own group values and behaviors are right and even better than all others. Feeling positive about one’s group is important for group solidarity and loyalty. However, it can lead groups and individuals to believe that certain racial or ethnic groups are inferior and that discriminatory practices against them are justified. This is called racism.

Although not all inequality can be attributed to racism, our nation’s history reveals that particular groups have been singled out and subject to unfair treatment. Certain groups have been subject to individual discrimination and institutional discrimination. Individual discrimination includes actions against minority members by individuals. Actions may range from avoiding contact with minority group members to physical or verbal attacks against minority group members. Institutional discrimination is practiced by the government, social institutions, and organizations. Institutional discrimination may include segregation, exclusion, or expulsion.

Segregation refers to the physical and social separation of ethnic or racial groups. Although we consider explicit segregation to be illegal and a thing of the past, ethnic and racial segregation still occurs in neighborhoods, schools, and personal relationships. According to Debra Van Ausdale and Joe Feagin (2001),

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection [LC-DIG-fsa-8a26761]

Jim Crow laws mandated the segregation of Whites and Blacks in public facilities, schools, and transportation in U.S. southern states. The laws were enforced until 1954 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that the racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 further prohibited racial discrimination, ending Jim Crow laws once and for all.

racial discrimination and segregation are still central organizing factors in contemporary U.S. society. For the most part, Whites and Blacks do not live in the same neighborhoods, attend the same schools at all educational levels, enter into close friendships or other intimate relationships with one another, or share comparable opinions on a wide variety of political matters. The same is true, though sometimes to a lesser extent, for Whites and other Americans of color, such as most Latino, Native and Asian American groups. Despite progress since the 1960s, U.S. society remains intensely segregated across color lines. Generally speaking, Whites and people of color do not occupy the same social space or social status. (p. 29)

Exclusion refers to the practice of prohibiting or restricting the entry or participation of groups in society. In March 1882, U.S. Congressman Edward K. Valentine declared, “The [immigration] gate must be closed” (Gyory 1998:238). That year, Valentine, along with other congressional leaders, approved the Chinese Exclusion Act. From 1882 to 1943, the United States prohibited Chinese immigration because of concerns that Chinese laborers would compete with American workers. The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 established national-origin quotas, giving priority to European immigrants. Through the 1940s, immigration was defined as a hindrance rather than a benefit to the United States.

p.56

Finally, expulsion is the removal of a group by direct force or intimidation. Native Americans in the United States were forcibly removed from their homelands by early settlers and the federal government before and after the American Revolutionary War. During the 1830s, members of the Cherokee and other nations were forcibly relocated to government-designated Indian territory (present-day Oklahoma). Their journey is known as the Trail of Tears, where thousands died along the way. In 2006, journalist Eliot Jaspin documented the extent of racial expulsion that occurred in towns from central Texas through Georgia. After the Civil War through the 1920s, White residents expelled nearly all Black persons from their communities, usually using direct physical force. Thirteen countywide expulsions were documented in eight states between 1864 and 1923 in which 4,000 Blacks were driven out of their communities.

SOCIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES ON RACIAL AND ETHNIC INEQUALITIES

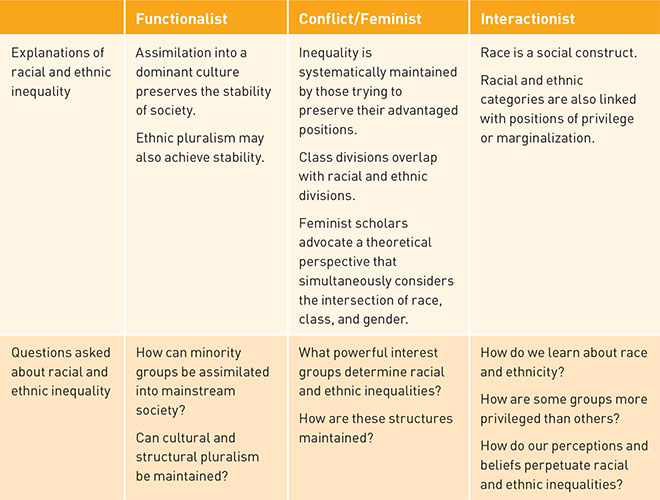

Functionalist Perspective

Theorists from the functionalist perspective believe that the differences between racial and ethnic groups are largely cultural. The solution is assimilation, a process whereby minority group members become part of the dominant group, losing their original distinct group identity. This process is consistent with America’s image as the “melting pot.” Milton Gordon (1964) presented a seven-stage assimilation model that begins first with cultural assimilation (change of cultural patterns, e.g., learning the English language), followed by structural assimilation (interaction with members of the dominant group), marital assimilation (intermarriage), identification assimilation (developing a sense of national identity, e.g., identifying as an American, rather than as an Asian American), attitude receptional assimilation (absence of prejudiced thoughts among dominant and minority group members), behavioral receptional assimilation (absence of discrimination; e.g., lower wages for minorities would not exist), and finally civic assimilation (absence of value and power conflicts).

Assimilation is said to allow a society to maintain its equilibrium (a goal of the functionalist perspective) if all members of society, regardless of their racial or ethnic identity, adopt one dominant culture. This is often characterized as a voluntary process. Critics argue that this perspective assumes that social integration is a shared goal and that members of the minority group are willing to assume the dominant group’s identity and culture, assuming that the dominant culture is the one and only preferred culture (Myers 2005). The perspective also assumes that assimilation is the same experience for all ethnic groups, ignoring the historical legacy of slavery and racial discrimination in our society.

Assimilation is not the only means to achieve racial/ethnic stability. Other countries maintain pluralism, where each ethnic or racial group maintains its own culture (cultural pluralism) or a separate set of social structures and institutions (structural pluralism). Cultural pluralism is also referred to as multiculturalism. Switzerland, which has a number of different nationalities and religions, is an example of a pluralistic society. The country, also referred to as the Swiss Confederation, has four official languages: German, French, Italian, and Romansh. Relationships between each ethnic group are described for the most part as harmonious because each of the ethnically diverse parts joined the confederation voluntarily seeking protection (Farley 2005). In his examination of pluralism in the United States, Min Zhou (2004) noted, “As America becomes increasingly multiethnic, and as ethnic Americans become integral in our society, it becomes more and more evident that there is no contradiction between an ethnic identity and an American identity” (p. 153).

p.57

Conflict Perspective

According to sociologist and activist W. E. B. Du Bois (1996), perhaps it is wrong “to speak of race at all as a concept, rather than as a group of contradictory forces, facts and tendencies” (p. 532). The problem of the 20th century, wrote Du Bois, is “the color line.”

Conflict theorists focus on how the dynamics of racial and ethnic relations divide groups while maintaining a dominant group. The dominant group may be defined according to racial or ethnic categories, but it can also be defined according to social class. Instead of relationships being based on consensus (or assimilation), relationships are based on power, force, and coercion. Ethnocentrism and racism maintain the status quo by dividing individuals along racial and ethnic lines (Myers 2005).

Drawing upon Marx’s class analysis, Du Bois was one of the first theorists to observe the connection between racism and capitalist-class oppression in the United States and throughout the world. He noted the link between racist ideas and actions to maintain a Eurocentric system of domination (Feagin and Batur 2004). Du Bois (1996) wrote,

Throughout the world today organized groups of men by monopoly of economic and physical power, legal enactment and intellectual training are limiting with great determination and unflagging zeal the development of other groups; and that the concentration particularly on economic power today puts the majority of mankind into a slavery to the rest. (p. 532)

Marxist theorists argue that immigrants constitute a reserve army of workers, members of the working class performing jobs that native workers no longer perform. Michael Samers (2003) suggested that immigrants are a “quantitatively and qualitatively flexible labour force for capitalists which divides and weakens working class organization and drives down the value of labour power” (p. 557). Capitalist businesses profit from migrant workers because they are cheap and flexible—easily hired during times of economic growth and easily fired during economic recessions. In 2013, approximately 60,000 immigrants worked in the federal detention centers, working for 13 cents an hour. Immigrants held in local county jails also worked for free or in exchange for sodas or candy. Their work usually involves meal preparation or janitorial work. This labor practice, though voluntary and cost-saving (about $40 million per year for federal detention centers), has come under attack by detainees and immigrant advocates (Urbina 2014). Several lawsuits have been filed against private-prison Immigration and Customs Enforcement contractors for exploiting and coercing immigrant labor.

Hana Brown (2013) posited a racialized conflict theory regarding the development of welfare policies. Her use of the term racialized (versus racial) emphasizes the constructed nature of race. Racialized conflicts are “a series of events that draw boundaries based on racial difference, polarize political groups along racial lines and involve explicitly race-based claims” (p. 401). Brown predicted several effects of racialized conflict on the formation of welfare policy. First, Whites may feel threatened by a larger or growing minority population and may perceive that minorities are too reliant on public assistance. These beliefs become institutionalized in the political discourse, transforming welfare into a racialized issue. Finally, racialized conflict divides political groups along racial lines and encourages political leaders to exploit the existing racialized tensions in their favor.

Brown offered empirical support of her hypotheses based on Georgia’s 1993–1994 welfare reform. Georgia’s welfare legislation was preceded by a controversial proposal by Governor Zell Miller to remove the Confederate emblem from the state flag. Response to his proposal was racially divided, with the majority of Whites opposing and the majority of Blacks supporting the governor. The flag proposal never materialized, but it ignited racial tension and racialized the state’s political discourse. Whites felt threatened by and resentful of Blacks, and this affected the welfare debate. According to Brown (2013), Miller’s decision to shift his attention from the state flag to welfare reform “proved a politically convenient way to appeal to white resentment and threat, exploit the prevailing racial discourses, and resurrect his political career” (p. 421). Georgia passed one of the strictest and most punitive welfare programs emphasizing work and education.

p.58

Feminist Perspective

Feminist theory has attempted to account for and focus on the experiences of women and other marginalized groups in society. Feminist theory intersects with multiculturalism through the analysis of multiple systems of oppression, not just gender, but including categories of race, class, sexual orientation, nation of origin, language, culture, and ethnicity. Most notably, Patricia Hill Collins’s (2000) Black feminist theory emerges from this perspective. Black feminists identify the value of a theoretical perspective that addresses the simultaneity of race, class, and gender oppression. The Black Lives Matter movement has embraced this intersectionality (refer to this chapter’s In Focus feature for more information).

Black feminist scholars note the misguided application of traditional feminist perspectives of “the family,” “patriarchy,” and “reproduction” to understand the experience of Black women’s lives. Black women do not lead parallel lives, but rather lead different lives. British scholar Hazel Carby (1985) argued that because Black women are subject to simultaneous oppression based on class, race, and patriarchy, the application of traditional (White) feminist perspectives is not appropriate and is actually misleading in attempts to comprehend the true experience of Black women. As an example, Carby (1985) analyzed an article on women in third-world manufacturing. Carby highlighted how the photographs accompanying the article are of “anonymous Black women.” She observed, “This anonymity and the tendency to generalize into meaninglessness, the oppression of an amorphous category called ‘Third World Women,’ are symptomatic of the ways in which the specificity of our experiences and oppression are subsumed under inapplicable concepts and theories” (Carby 1985:394).

Applying theoretical perspectives from Black and postcolonial feminist theory, Cecile Thun (2012) explained how immigrant women are minoritized and excluded from the majority feminist agenda in Norway. Based on her interviews with members of feminist organizations, Thun concluded that White Norwegian women are defined as the norm for being a woman or a feminist, while other women are considered deviant and are subsequently excluded from the majority feminist agenda. In other words, ethnic minority and immigrant women are not considered Norwegian women. She argued this is a “hegemonic representation of feminism, immigrants/ethnic minorities and Norwegians are constituted as mutually exclusive categories. . . . Immigrants are thereby excluded from the imagined Norwegian nation. The terms have elements of hierarchy and work as boundary markers” (p. 46). She suggested opening up a more intersectional perspective to include racism and ethnic discrimination in the Norwegian feminist agenda.

Interactionist Perspective

Sociologists believe that race is a social construct. We learn about racial and ethnic categories of White, Black, Latino, Asian, Native American, and immigrant through our social interaction. The meaning and values of these and other categories are provided by our social institutions, families, and friends (Ore 2003). As much as I and other social scientists inform our students about the unsubstantiated use of the term race, for most students, race is real. The term is loaded with social, cultural, and political baggage, making deconstructing it difficult to accomplish.

p.59

IN FOCUS

BLACK LIVES MATTER

“Black lives matter is a simple affirmative sentence,” wrote theological scholar Wil Gafney (2017:204). “The need to affirm, explain, or qualify the affirmation stems from the fact that this statement is not universally accepted as truthful or legitimate claim. Concomitantly, the inverse proposition is always present: Black lives do not matter. That proposition requires no amplification for explanation. It is the ground on which all other claims about black life seem to rest in this society.” According to Judith Butler, “The statement is so important because it states the obvious, but the obvious has not yet been historically realized” (quoted in Yancy and Butler 2015).

The phrase Black Lives Matter (BLM) was first used by activist Alicia Garza on a Facebook post in July 2012. Garza and others were responding to the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. The use of #BlackLivesMatter swelled on Twitter and Facebook in summer 2014 after the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. The movement has been described as a “powerful new form of civil rights activism” combining street protest with social media (Joseph 2016).

According to Lee Rainie, Pew Center’s Director of Internet, Science and Technology Research, BLM “is a very powerful example of how a hashtag now is attached to a movement, and a movement, in some ways has grown around a hashtag—a series of really painful and really powerful conversations are taking place in a brand-new space” (quoted in Choski 2016). BLM is best known for its protests of fatal police shootings of unarmed African American men.

Support of the movement has not been universal. Critics claim that the group has been ineffectual, without a clear direction or strategy. Others have described the group as a threat. BLM cofounder Patrisse Cullors offered this response, “Black Lives Matter is very relevant today, especially given the rise of white supremacists and white nationalists across, not just this country, but across the globe. And so our work over the last four years has been putting anti-black racism on the map, talking about the impact of anti-black racism has on this country, has on local government, has on policy and how it actually impacts the everyday life of black people” (quoted in Simmons and Kaleem 2017).

Black Lives Matter has transformed into an intersectional movement, calling out the oppression and marginalization of women, LGBTQ individuals, the disabled, undocumented and other groups, and has expanded its focus to social policy and legislative reforms. As of August 2017, BLM has 40 independent chapters, including chapters in Canada and Britain.

In November 2017, the group was awarded the Sydney Peace Prize, Australia’s leading award for global peacemakers.

Social scientists have noted how people are raced, how race itself is not a category but a practice. Howard McGary (1999) defined the practice as “a commonly accepted course of action that may be over time habitual in nature; a course of action that specifies certain forms of behavior as permissible and others impermissible, with rewards and penalties assigned accordingly” (p. 83). In this way, racial categories and identities serve as intersections of social beliefs, perceptions, and activities that are reinforced by enduring systems of rewards and penalties (Shuford 2001). Racial practices are not uniform. For example, whereas in the United States we are accustomed to racial categorizations (e.g., the Census Bureau’s race measurement), France’s census does not include measures for race, ethnicity, or religion.

Individuals are attempting to redefine racial boundaries by proposing the creation and acknowledgment of a new racial category: multiracial, or mixed race. This is different from other ethnic movements that work within the existing racial frameworks. For example, Latinos may challenge the meaning and use of the Census category Hispanic, but they are not trying to create a new racial identity (DaCosta 2007). Members of the multicultural movement advocate the formal acceptance of the multiracial category on U.S. Census and other governmental forms and have also worked on broader issues of racial and social justice (Bernstein and De la Cruz 2009). Based on a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, 7% of U.S. adults identified having a mix or multiple race background (Pew Research Center 2015a).

Scholars have also observed the phenomenon of ethnic attrition, individuals choosing not to self-identify as a member of a particular ethnic group. Brian Duncan and Stephen Trejo (2011) found that about 30% of third-generation Mexican youth in their study failed to identify as Mexican, choosing instead to identify as White. These youth were more likely to have parents with higher levels of educational attainment and have more years of schooling themselves than youth who identified as Mexican. Scholars of race in Latin America have also confirmed patterns of intergenerational Whitening. Highly educated non-White Brazilians were found to be more likely to label their children White than less-educated non-White Brazilians (Schwartzman 2007).

A summary of all theoretical perspectives is provided in Table 3.3.

p.60

TABLE 3.3 ■ Summary of Sociological Perspectives: Inequalities Based on Race and Ethnicity

THE CONSEQUENCES OF RACIAL AND ETHNIC INEQUALITIES

U.S. Immigration

Most U.S. families have an immigration history, whether it is based upon stories of relatives as long as four generations ago or as recent as the current generation. Immigration involves leaving one’s country of origin to move to another. The United Nations uses the analogy of multiple doors of a house to describe the different ways migrants enter a country. Migrants can enter a house through the front door (as permanent settlers), the side door (temporary visitors and workers), or the back door (undocumented migrants). Back-door migrants have been the recent focus of much political and economic debate.

The regulation of immigration became a federal responsibility in 1875, and the Immigration Service was established in 1891. Before this, all immigrants were allowed to enter and become permanent residents. The Great Wave of immigration occurred from 1900 to 1920, when nearly 24 million immigrants, mostly European, arrived in the United States. Congress passed a national immigrant quota system in 1921, limiting the number of immigrants by national groups based on their representation in U.S. Census figures. The quota system, along with the Depression and World War II, slowed the flow of immigrants for several decades.

In 1965, Congress replaced the national quota system with a preference system designed to reunite immigrant families and attract skilled immigrants. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act is credited with transforming the U.S. demographic profile. The percentage of immigrants in the U.S. population grew from 5% of the population in 1965 to 14% in 2015 (Pew Research Center 2015b).

During President George W. Bush’s term in office (2001–2009), undocumented immigration became a primary concern for Americans, responding to the threat of terrorism and increasing competition in a struggling economy. The number of unauthorized immigrants peaked at 12 million in 2007 (Krogstad and Passel 2014). While acknowledging the country’s immigration heritage, the administration proposed strengthening security at our southern border with Mexico and establishing a temporary worker program without the benefit of amnesty. The plan was criticized for creating a class of workers who would never become fully integrated in U.S. society and for focusing specifically on Mexican workers, ignoring all other immigrant groups.

p.61

Many of those against immigration claim that immigrants compete with U.S.-born workers for jobs. This argument persists in spite of consistent economic and labor force analyses that confirm how immigrants are a positive addition to the economy (Borjas 1994) and have little effect on wages and employment of native workers (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine 2017). Prior immigrants (those who are most often the substitutes for newer arriving immigrants) are most likely to experience a decline in wages, followed by native-born high school dropouts (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine 2017).

As of 2016, the number of unauthorized immigrants was estimated at 11.3 million (Krogstad, Passel, and Cohn 2017). According to Jens Manuel Krogstad, Jeffrey Passel, and D’Vera Cohn (2017), there were 5.6 million Mexican unauthorized immigrants living in the United States in 2015 and 2016, compared with a peak of 7 million in 2007. The number of unauthorized immigrants from nations other than Mexico were estimated to be slightly higher at 5.7 million. The emigration decline of those from Mexico has been attributed to the Great Recession, declining job opportunities in the housing and construction industry, increasing border enforcement, a rise in deportations, and increasing dangers associated with border crossings (Krogstad and Passel 2014). However, as Joseph Healey and Eileen O’Brien (2017) observed, “like past waves of immigrants, even the least skilled and educated are determined to find a better way of life for themselves and their children, even if the cost of doing so is living on the margins of the larger society” (p. 303).

Although there are no industries in which immigrants outnumber the U.S.-born employees, lawful and unauthorized immigrants are concentrated in specific industries. For 2014, the top industry for lawful immigrants was retail (10% of lawful immigrants), educational services (8%), and non-hospital health care services. For unauthorized immigrant workers, the leading industries were construction (16%), restaurants (14%), and administrative and support services (9%) (Desilver 2017). Refer to this chapter’s Exploring Social Problems feature for a closer look at the characteristics of the recently arrived immigrant population.

©David McNew/Getty Images

On February 16, 2017, businesses shut down and immigrants refused work or to spend money in protest of the Trump administration’s immigration policies. The Day Without Immigrants was staged to show the country what an economy without immigrant labor would mean for our way of life.

Immigration enforcement practices were intensified under President Bush’s administration. One strategy included increasing U.S.–Mexico border patrol and enforcement. However, Douglas Massey, Jorge Durand, and Karen Pren (2016) argued that the escalation of border enforcement was a failure. Although most believed that increased border enforcement would slow undocumented immigration, the researchers found that enforcement had several unexpected consequences. As the cost of undocumented border crossing increased, undocumented migrants had to stay in the United States longer to make the crossing profitable. As the risk of death and injury increased with each border crossing, migrants made the decision to minimize their number of crossings, not by remaining in Mexico but by staying in the United States.

The Department of Homeland Security and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement have been criticized for targeting immigrants with minor offenses, sometimes breaking up families in the process. Human Rights Watch (2009) reported that since stricter deportation laws were passed in 1996, most immigrants have been deported for minor offenses (such as marijuana possession or traffic offenses). Among legal immigrants who were deported, over 70% had been convicted for nonviolent crimes. Many had lived in the United States for years and were separated from family members. Researchers from the Urban Institute documented short- and long-term effects on children with deported or detained parents. These children experienced financial, food, and housing hardships in addition to behavioral changes such as changes in eating and sleeping habits and higher degrees of fear and anxiety (Chaudry et al. 2010).

p.62

EXPLORING

SOCIAL PROBLEMS

RECENTLY ARRIVED IMMIGRANT POPULATION

According to the Pew Research Center (2015c), recently arrived immigrants are different from their counterparts of 50 years ago.

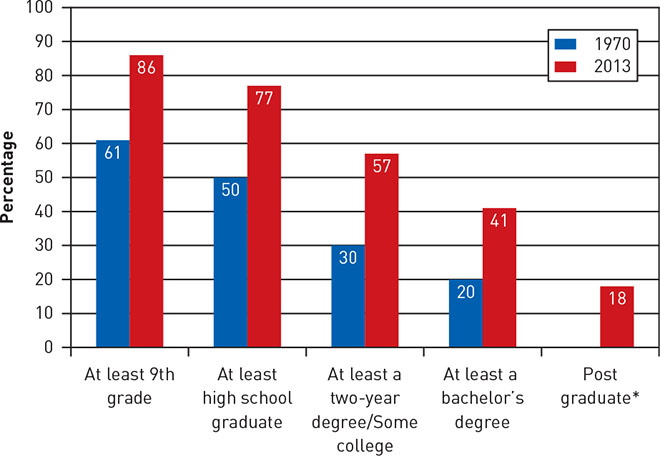

Figure 3.2 displays the educational attainment of immigrants between 1970 and 2013 (Pew Research Center 2015c). Those coming to the United States are better educated than earlier cohorts. For example, half of newly arrived immigrants in 1970 had at least a high school degree, but in 2013, 77% did. Improved educational levels are the result of rising educational attainment in countries of origin. In the highest educational categories (data not shown), immigrants are more likely than their U.S.-born peers to have earned a bachelor’s degree (41% of immigrants vs. 30% of native born) or an advanced degree (18% of immigrants vs. 11% of native born).

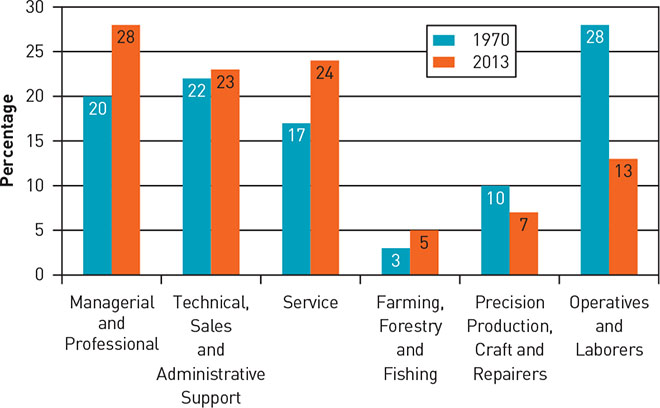

Data presented in Figure 3.3 summarizes the occupation distribution of recently arrived immigrants. Based on 2013 data, which occupations are recently arrived immigrants most likely to be employed in? How has this changed from 1970? What do you think? Does this confirm or contradict your perception of immigrant employment?

FIGURE 3.2 ■ Educational Attainment of Immigrants Aged 25 and Older (Percentages), 1970 and 2013

Source: Pew Research Center 2015c.

* No available data for 1970.

FIGURE 3.3 ■ Occupation Distribution of Recently Arrived Immigrants (1970 and 2013)

Source: Pew Research Center 2015c.

p.63

TAKING A WORLD VIEW

GLOBAL IMMIGRATION

Migration has been elevated to a top international policy concern (Düvell 2005), largely because of the threat of terrorism and the challenge of global politics. Migrants now depart from and arrive in almost every country in the world. Politically and morally, migration pits two basic principles against each other: On one hand is the right of individuals to move freely across borders for economic or personal reasons, and on the other is the country’s right to self-govern, to regulate its borders, and to determine the difference between a citizen and an alien (Benhabib 2012). France, Germany, Greece and other countries have seen an increase in pro- and anti-immigration protests, as well as increased hate crime acts against immigrants. In 2018, far-right and populist candidates swept Italy’s national election, running on platforms that embraced anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim messaging.

Riots by immigrants took place in France in 2005 and in Italy during 2008–2010. In Italy, there are 4 million legal immigrants and estimates of more unauthorized immigrants residing in the country. Flavio Di Giacomo, a spokesman for the International Organization for Migration, described how immigrant workers live in semislavery. The riots, according to Di Giacomo, revealed how “many Italian economic realities are based on the exploitation of low-cost foreign labor, living in subhuman conditions, without human rights” (Donadio 2010a:A7). The African laborers were paid under the table, about $30 a day, for picking fruit (Donadio 2010b). Asian and African immigrants in Greece have been the targets of violence and physical attacks since 2010. The violence has been fueled by public discontent over the economy and concern over job losses as well as demonization of immigrants in the press and in the political arena. From a social constructionist’s perspective, immigrants were portrayed as the source of Greece’s economic woes, defining them as a social problem and threat.

Migration flows are regarded as a threat to national and global stability, with some calling for an international migration policy (Düvell 2005). Globalization has intensified the need to coordinate and harmonize government policies. The United States, Canada, Great Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Spain, and Japan have increased policy coordination regarding immigration, refugee admissions, and programs to integrate foreigners and their family members already present in each country (Lee 2006). Several countries have instituted immigration quotas and restrictions. In 2014, Swiss voters narrowly approved immigration quotas for European Union citizens. (Switzerland is not a member of the European Union.) Analysts describe the vote as a response to a growing concern that immigrants are eroding the Swiss lifestyle and culture. According to the European Commission, the vote went against the principle of the free movement of people (Baghdjian and Schmieder 2014).

From 2015 to 2017, the European Union struggled to relocate the thousands of asylum seekers from the Middle East, Afghanistan, and Africa. In 2017, the Court Justice of the European Union ruled that all EU countries were obligated to accept migrants under an established quota system. Hungary and Slovakia refused to accept any refugees (Kanter 2017).

Would you support the closing of our borders to all new immigrants? Why or why not?

What Does It Mean to Me?

Immigration is part of a complex interdependent system, where native-born Americans depend on immigrants for their labor and immigrants depend on the economic opportunities that are available in U.S. society. Is immigration defined as a problem in your state? Who is affected and how?

Income and Wealth

“Race is so associated with class in the United States that it might not be direct discrimination, but it still matters indirectly,” says sociologist Dalton Conley (Ohlemacher 2006:A6). Data reported by the U.S. Census reveal that Black households had the lowest median income in 2015 ($39,490), or 61% of the median income for non-Hispanic White households ($65,041). The median income for Hispanic households was $47,675, 73% of the median for non-Hispanic White households. Asian households had the highest median income ($81,431), 125% of the median for non-Hispanic White households (Semega, Fontenot, and Kollar 2017). Approximately 17% of all foreign born were living in poverty in 2015 (Lopez and Radford 2017).

p.64

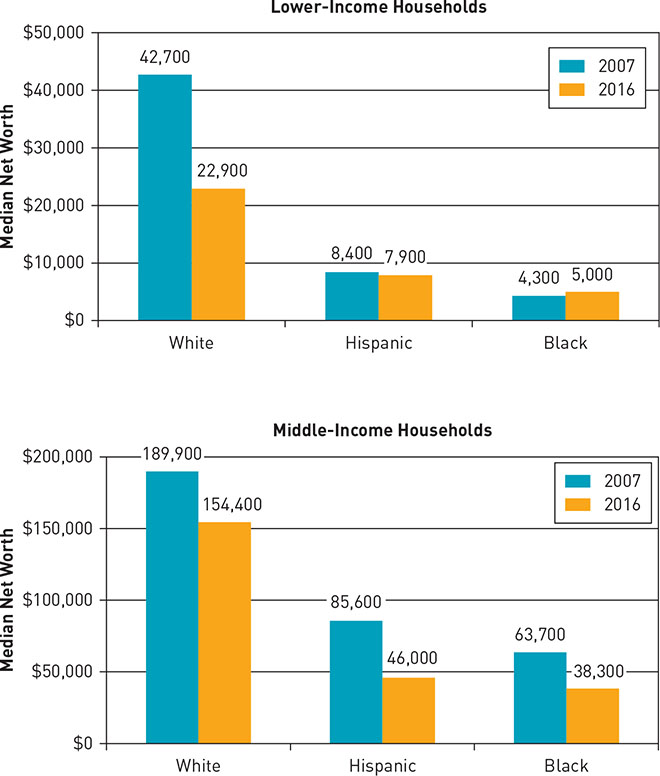

Because of years of discrimination, low educational attainment, high unemployment, or underemployment, Blacks and Hispanics have not been able to achieve the same earnings or level of wealth as White Americans have. Rakesh Kochhar and Anthony Cilluffo (2017) documented how the Great Recession of 2007–2009 set in motion a prolonged decline in wealth of American families, widening the wealth gap between White, Black, and Hispanic households. Net worth is defined as the difference between a family’s gross assets and their liabilities. Comparing 2007 and 2016 median net worth for lower-income households, White families experienced greater losses in wealth during the recession than Hispanic and Black families. In 2016, among lower- and middle-income households, White families had four times as much wealth as Black families and three times as much as Hispanic families (refer to Figure 3.4).

FIGURE 3.4 ■ Median Net Worth of Lower- and Middle-Income Households by Race (in 2016 Dollars), 2016

Source: Kochhar and Cilluffo 2017.

p.65

One measure of wealth is home ownership. Home ownership is one of the primary means of accumulating wealth (Williams, Nesiba, and Diaz McConnell 2005). It enables families to finance college and invest in their future. Historically, home ownership grew among White middle-class families after World War II, when veterans had access to government and credit programs that made home ownership more affordable. However, Blacks and other minority groups have been denied similar access because of structural barriers such as discrimination, low income, and lack of credit access. Feagin (1999) identified how inequality in home ownership has contributed to inequality in other aspects of American life. Specifically, Blacks have been disadvantaged because of their lack of home ownership, particularly in their inability to provide their children with “the kind of education or other cultural advantages necessary for their children to compete equally or fairly with Whites” (Feagin 1999:86).

In 2004, U.S. home ownership reached a record high of 69.2%, with nearly 73.4 million Americans owning their own homes. However, racial gaps in home ownership persist. In the third quarter of 2017, 72.5% of White households owned their own homes, compared with 42% of Black and 46% of Hispanic households (U.S. Census Bureau 2017).

Education

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education ruled that racial segregation in public schools was illegal. Reaction to the ruling was mixed, with a strong response from the South. A major confrontation occurred in Arkansas, when Governor Orval Faubus used the state’s National Guard to block the admission of nine Black students into Little Rock Central High School. The students persisted and successfully gained entry to the school the next day with 1,000 U.S. Army paratroopers at their side. The Little Rock incident has been identified as a catalyst for school integration throughout the South. Despite resistance to the Court’s ruling, legally segregated education had disappeared by the mid-1970s.

However, a different type of segregation persists, called de facto segregation. De facto segregation refers to a subtler process of segregation that is the result of other processes, such as housing segregation, rather than an official policy (Farley 2005). Here, we clearly see the intersection of race and class. Schools have become economically segregated, with children of middle- and upper-class families attending predominantly White suburban schools and the children of poorer parents attending racially mixed urban schools (Gagné and Tewksbury 2003). Researchers, teachers, and policy makers have all observed a great disparity in the quality of education students receive in the United States (for more on social problems related to education, turn to Chapter 8). Educational systems reinforce patterns of social class inequality and, along with it, racial inequality (Farley 2005).

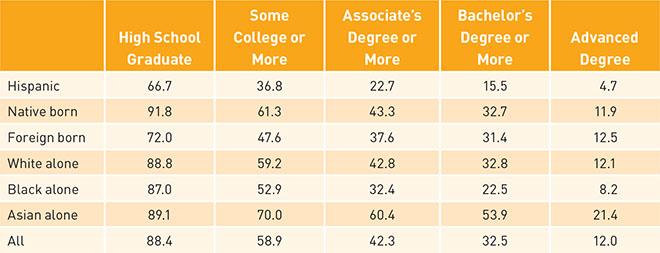

Although Latinos have the lowest educational achievement rates compared with all other major racial and ethnic groups in the United States (refer to Table 3.4), there has been a recent increase in rates of high school completion and college enrollment. Richard Fry and Paul Taylor (2013) reported that for the class of 2012, 69% of Hispanic high school graduates enrolled in college, compared with 67% of their White student peers. This percentage is an increase from what was reported for the class of 2000, when only 49% of Hispanic high school graduates enrolled in college. Fry and Taylor attributed the increase in Hispanic college enrollment to two structural factors: a tough and competitive job market and the importance Latino families place on a college education. In 2016, 47% of Hispanic high school graduates enrolled in college, the same figure as their White peers (Pew Research Center 2017).

TABLE 3.4 ■ Educational Attainment of Population Age 25 and Older by Race and Ethnicity (Percentages Reported), 2015

Source: Data from U.S.Census Bureau, 2015 Current Population Survey.

Much of the research on the achievement gap between Latinos and White students has focused on the characteristics of the students (family income, parents’ level of education). However, according to the Pew Hispanic Center (Fry 2005), we need to also consider the social context of Hispanic students’ learning, noting how educators and policy makers have more influence over the characteristics of their schools than over the characteristics of students. Based on their state and national assessment of the basic characteristics of public high schools for Hispanic and other students, the Pew Hispanic Center found that Latinos were more likely than Whites or Blacks to attend the largest public high schools (enrollment of at least 1,838 students). More than 56% of Hispanics attend large schools, compared with 32% of Blacks and 26% of Whites. Schools with larger enrollments are associated with lower student achievement and higher dropout rates. In addition, the center reported that Hispanics are more likely to be in high schools with lower instructional resources, including higher student-to-teacher ratios, which has been associated with lower academic performance. Nearly 37% of Hispanics are educated in public high schools with a student-to-teacher ratio greater than 22 to 1, compared with 14% of Blacks and 13% of White students (Fry 2005).

p.66

In June 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court, voting 5 to 4, invalidated the use of race to assign students to public schools, even if the goal was to achieve racial integration of a district’s schools. The ruling addressed public school practices in Seattle, Washington (where 41% of all public school students are White), and Louisville, Kentucky (where two thirds of all public school students are White). Legal experts and educators were divided about whether the ruling affirmed or betrayed Brown v. Board of Education. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts asserted, “Simply because the school districts may seek a worthy goal [racial integration] does not mean they are free to discriminate on the basis of race to achieve it.” Despite voting with the majority, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy said in a separate statement that achieving racial diversity and addressing the problem of de facto segregation were issues that school districts could constitutionally pursue as long as the programs were “sufficiently ‘narrowly tailored’” (Greenhouse 2007:A1).

Health

“Although race may be a social construct, it produces profound biological manifestations through stress, decreased services, decreased medications, and decreased hospital procedures” (Gabard and Cooper 1998:346). Despite the full implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), racial disparities in access to health care and outcomes are pervasive. Data reveal that in a voluntary, employment-based health care system, racial and ethnic minority group members are more likely to be uninsured or publicly insured. In 2016, White non-Hispanics had the lowest uninsured rate (6.3%), compared with Blacks (15.9%), Asians (7.6%), and Hispanics (16%) (Barnett and Berchick 2017). Naturalized citizens have the same ACA access and requirements as U.S.-born citizens, while lawfully present immigrants have limited coverage. Undocumented immigrants have no federal coverage, but they are eligible for emergency care under federal law and nonemergency health services at community health centers. Children of undocumented parents are eligible for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

p.67

W. Michael Byrd and Linda Clayton (2002) asserted that the health crisis among African Americans and poor populations is fueled by a medical-social culture laden with ideological, intellectual and scientific, and discriminatory race and class problems. They believe that America’s health system is predicated on the belief that the poor and “unworthy” of our society do not deserve decent health. Consequently, health professionals, as well as research and educational systems, engage in what they describe as “self serving and elite behavior” that marginalizes and ignores the problems of health care for minority and disadvantaged groups. They caution that our failure to address, and eventually resolve, these race- and class-based health policy, structural, medical-social, and cultural problems plaguing the American health care system could potentially undermine any possibility of a level playing field in health and health care for African American and other poor populations—eroding at the front end the very foundations of American democracy (Byrd and Clayton 2002:572–73).

One solution to addressing racial disparities in health is to increase awareness of the problem. A national survey concluded that only 46% of American adults were aware of health disparities between Whites and Blacks. The study also revealed that most Americans attributed poor health outcomes to poor choices and health behaviors rather than the social conditions that initiate and sustain them (Booske, Robert, and Rohan 2011). However, increasing public awareness does not guarantee that people will want to act upon these inequalities. The next step would be to connect the problem of poor health outcomes with racial inequality and racism. It isn’t just about saying racial and ethnic health disparities exist but also identifying the source of the disparities, possibly building a political climate to facilitate social change (Williams and Purdie-Vaughns 2016).

In the next section, other responses to racial and ethnic inequalities are identified.

RESPONDING TO RACIAL AND ETHNIC INEQUALITIES

Immigration Policy Since 2009

According to sociologist Joanna Dreby (2015), “No immigration policy, except for an entirely open system of immigration, can completely remove unauthorized individuals. From this perspective, the question is not how to eliminate the number of unauthorized but what approach to use in dealing with this population” (p. 191). Since the George W. Bush administration was in office, there have been several federal and state approaches to addressing immigration.

In 2009, as the Bush plan had, Obama officials promoted the need for tougher enforcement laws against undocumented immigrants and employers who hire them, a streamlined system for legal immigration, and a system for undocumented immigrants to earn legal status (Preston 2009). At the same time, the Obama administration promised a more compassionate approach to enforcement that would focus on felony criminal offenders. In 2011, 396,906 immigrants were deported—the largest number in the history of Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Fifty-five percent were convicted of felonies or misdemeanors (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement 2011). The Obama administration’s continued focus on punitive enforcement strategies was criticized for failing to encourage and promote assimilation among immigrants and their children. Nationwide polls showed broad support for tougher border and workplace enforcement, while also establishing an opportunity for citizenship.

After the U.S. Congress was unable to pass a bipartisan immigration bill, the states took matters into their own hands, debating similar immigration issues in their own state legislatures (Preston 2007). Between 2005 and 2011, more than 8,000 bills related to immigration were introduced throughout the country, and approximately 1,700 were signed into law (National Conference of State Legislatures 2011). These laws addressed a range of immigration issues, including the use of unauthorized illegal workers, the use of false identification (e.g., Social Security), and the extension of education and health care benefits to legal immigrants.

Arizona legislators passed senate bill (SB) 1070, the toughest immigration bill, in 2010, requiring local law enforcement agencies and officers to demand proof of citizenship from suspected illegal immigrants. Failure to carry proper documentation, even if one is a legal immigrant, is defined as a misdemeanor. In 2011, 31 states introduced legislation replicating all or part of SB 1070. Voters in five states—Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina, and Utah—successfully passed immigration laws modeled after SB 1070. In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld part of Arizona’s law, permitting the “show me your papers” provision, while ruling that the state could not pursue policies that undermined or conflicted with federal law, for example, by making it a crime under state law for immigrants to fail to register under a federal law, making it a state crime for illegal immigrants to work, and allowing police to arrest individuals without warrants (Liptak 2012). In 2016, as part of a settlement with a coalition of immigrant rights groups, Arizona’s state attorney general announced that police officers would no longer demand proof of residency from people suspected of being in the country illegally, eliminating the “show me your papers” provision.

p.68

©Melanie Stetson Freeman/The Christian Science Monitor via Getty Images

DACA student Evelin Flores attends Eastern Conneticut State University. Her family brought her from Mexico when she was a baby. Flores recieves scholarship support from The Dream US scholarship program.

The impact of immigration, especially on youth and young adults, has been the focus of federal and state government debate. Second generation applies to those born in the United States to one or more foreign-born parents. Based on key measures of socioeconomic attainment (income, college graduation, home ownership, and poverty rates), most second-generation Americans are better off than first-generation Americans. Their characteristics resemble the full U.S. adult population (Pew Research 2013). In contrast, the 1.5 generation refers to individuals who immigrated to the United States as a child or an adolescent. The parents of the 1.5 generation are foreign born. Members of the 1.5 generation are described as living between two worlds; even though they spend most of their life in the United States, they still are not legal citizens.

Through executive action, in 2012 the Obama administration blocked the deportation of more than 800,000 migrants who came to the United States before age 16 (Preston and Cushman 2012; White House 2012). The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) allows those who have lived in the United States for at least five years and are currently enrolled in school, high school graduates, or military veterans in good standing to work legally and to obtain driver’s licenses. Immigrants convicted of a felony, a serious misdemeanor, or three less serious misdemeanors are not eligible for the program. As of March 2018, there were approximately 700,000 active DACA recipients (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services 2018).

As congressional gridlock on immigration continued in 2014, President Obama announced a series of executive actions that would grant up to 5 million unauthorized immigrants protection from deportation. His order created a deferred action program for parents of U.S. citizens. Undocumented immigrant parents would have to pass background checks, pay fees, and show that their child was born before the president’s announcement. The president also announced the extension of DACA eligibility to men and women who entered the United States as children before January 2010, regardless of how old they are today (White House 2014).

In September 2017, President Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced plans to phase out DACA, giving Congress six months to devise a legislative solution that would provide some of the DACA protections. President Obama (2017) responded to the announcement, saying in part, “That action today isn’t required legally. It’s a political decision, and a moral question. Whatever concerns or complaints Americans may have about immigration in general, we shouldn’t threaten the future of this group of young people who are here through no fault of their own, who pose no threat, who are not taking anything away from the rest of us.” A series of federal court rulings placed a temporary stay on President Trump’s plan to end DACA and removed the congressional deadline. As of June 2018, no new DACA legislation has been introduced in Congress. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services will continue accepting DACA renewal applications.

p.69

Under the Trump administration, the U.S. Department of Justice has executed 49,983 orders of removal for unauthorized immigrants, up 27.8% over the same time period in 2016 (U.S. Department of Justice 2017). Agents are now permitted to arrest and deport anyone who is here illegally. In December 2017, in an effort to discourage future border crossings, the Trump administration announced plans to separate parents from their children if they are caught illegally entering the country. Migrant advocates argued that the policy would jeopardize the safety of the families fleeing Central America and would inflict devastating trauma on the children (Miroff 2017).

Affirmative Action

Since its inception 50 years ago, affirmative action has been a “contentious issue on national, state, and local levels” (Yee 2001:135). Affirmative action is a policy that has attempted to improve minority access to occupational and educational opportunities (Woodhouse 2002). No federal initiatives enforced affirmative action until 1961, when President John Kennedy signed Executive Order 10925. The order created the Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity and forbade employers with federal contracts from discriminating on the basis of race, color, national origin, or religion in their hiring practices. In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination based on race, color, religion, or national origin by private employers, agencies, and educational institutions receiving federal funds (Swink 2003).

In June 1965, during a graduation speech at Howard University, President Johnson spoke for the first time about the importance of providing opportunities to minority groups, an important objective of affirmative action. According to Johnson (1965),

you do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him to the starting line of a race and then say, “You are free to compete with all others” and still justly believe you have been completely fair. Thus it is not enough just to open the gates of opportunity. All our citizens must have the ability to walk through those gates. This is the next and the more profound stage of the battle for civil rights. We seek not just freedom but opportunity. (p. 636)

EMPLOYMENT In September 1965, President Johnson signed Executive Order 11246, which required government contractors to “take affirmative action” toward prospective minority employees in all aspects of hiring and employment. Contractors are required to take specific proactive measures to ensure equality in hiring without regard to race, religion, and national origin. The order also established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), charged with enforcing and monitoring compliance among federal contractors. In 1967, President Johnson amended the order to include discrimination based on gender (Swink 2003). In 1969, President Richard Nixon initiated the Philadelphia Plan, which required federal contractors to develop affirmative action plans by setting minimum levels of minority participation for federal construction projects in Philadelphia and three other cities (Idelson 1995). This was the first order that endorsed the use of specific goals for desegregating the workplace (Kotlowski 1998), but it did not include fixed quotas (Woodhouse 2002). India’s affirmative action program relies on quotas in the public (government) sector. In Northern Ireland, affirmative action is practiced in public and private sectors, including government contractors, and does not rely on quotas (Muttarak et al. 2013).

According to Dawn Swink (2003), “While the initial efforts of affirmative action were directed primarily at federal government employment and private industry, affirmative action gradually extended into other areas, including admissions programs in higher education” (pp. 214–15). State and local governments followed the lead of the federal government and took formal steps to encourage employers to diversify their workforces.

p.70

Opponents of affirmative action believe that such policies encourage preferential treatment for minorities (Woodhouse 2002), giving women and ethnic minorities an unfair advantage over White males (Yee 2001). Affirmative action, say its critics, promotes “reverse discrimination,” the hiring of unqualified minorities and women at the expense of qualified White males (Pincus 2003). Some believe affirmative action has not worked and ultimately results in the stigmatization of those who benefit from the policies (Herring and Collins 1995; Heilman, Block, and Stahatos 1997).

Proponents argue that only through affirmative action policies can we address the historical societal discrimination that minorities experienced in the past (Kaplan and Lee 1995). Although these policies have not created true equality, there have been important accomplishments (Tsang and Dietz 2001). As a result of affirmative action, women and people of color have gained increased access to forms of public employment and education that were once closed to them (Yee 2001). Yet research indicates that ethnic minorities and women do not have an unfair advantage over White men. Women and ethnic minorities are not receiving equal compensation compared to White males with similar education and background (Tsang and Dietz 2001). Wage disparities and job segregation continue to exist in the workplace (Harris 2009).

G. L. A. Harris (2009) explained that although the record on affirmation action is mixed, there is evidence that without the policy and the use of gender, race, and/or other ethnicity as part of the employment hiring process, the employment status of women and underrepresented minorities would be worse. Affirmative action has been the “only comprehensive set of policies that has given women and people of color opportunities for better paying jobs and access to higher education that did not exist before” (Yee 2001:137). There is also evidence that White employees benefit from the inclusion of these groups in the workplace; for example, companies with more than 100 employees with affirmation action programs have higher earnings for Whites, women, and minority employee groups (Pincus 2003).

Shawn Woodhouse (1999, 2002) argued that the differences in individual perceptions of affirmative action policy may be related to the differences of racial group histories and socialization experiences. She wrote,

Based upon these rationalizations, it is implicit that individuals interpret affirmative action through an ethnic specific lens. In other words, most individuals will assess their group condition when considering contentious legislation such as affirmative action because after all, a group’s history impacts its view of American society. (Woodhouse 2002:158)

EDUCATION Based on Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, affirmative action policies have been applied to student recruitment, admissions, and financial aid programs. Title VI permits the consideration of race, national origin, sex, or disability to provide opportunities to a class of disqualified people, such as minorities and women, who have been denied educational opportunities. Affirmative action policies have been supported as remedies for past discrimination as means of encouraging diversity in higher education and as a tool for social justice. Such policies also have economic motivations, helping disadvantaged populations achieve economic self-sufficiency. Affirmative action practices were affirmed in the 1978 Supreme Court decision in the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, suggesting that race-sensitive policies were necessary to create diverse campus environments (American Council on Education and American Association of University Professors 2000; Springer 2005).

Although affirmative action has been practiced since the Bakke decision, it has been under attack, particularly via challenges of the diversity argument in the Supreme Court’s decision. The first challenge occurred in one of our most diverse states, California. In 1995, the California Board of Regents banned the use of affirmative action guidelines in admissions. In 1996, California voters followed and passed Proposition 209, the California Civil Rights Initiative, which effectively dismantled the state’s affirmative action programs in education and employment. Also in 1996, a federal appeals court ruling struck down affirmative action in Texas. In the Hopwood v. Texas decision, the ruling referred to affirmative action policies as a form of discrimination against White students. State of Washington voters passed an initiative in 1998 that banned the use of race-conscious affirmative action in schools. In 1999, Florida governor Jeb Bush banned the use of affirmative action in admission to his state’s schools.

p.71

The Hopwood ruling led to a decline in the number of minority students enrolling in Texas A&M and the University of Texas (Yardley 2002). California’s state universities experienced a similar drop in minority student applications and enrollment after the Bakke decision and the California Civil Rights Initiative. In response, states have instituted other practices with the goal of increasing minority student recruitment. For example, California and Texas have initiated percentage solutions. In Texas, the top 10% of all graduating seniors are automatically admitted into the University of Texas system. (In 2009, the Texas Legislature voted to put limits on the program, setting enrollment caps on the number of students let in under the rule at 75% of the entering class.) California initiated a similar plan, covering only the top 4% of students, and Florida implemented the One Florida Initiative, allowing the top 20% of graduating high school seniors into the state’s public colleges and universities (Schemo 2001). As of 2014, all three plans remain in effect.

For more than a decade, the University of Michigan’s affirmation action program has been disputed. In 2000, a federal judge upheld the University of Michigan’s program, ruling that “a racially and ethnically diverse student body produces significant educational benefits such that diversity, in the context of higher education, constitutes a compelling governmental interest” (Wilgoren 2000:A32). In 2003, the case was considered by the U.S. Supreme Court, and in a 5 to 4 vote, the Court upheld the University of Michigan’s consideration of race for admission into its law school. Writing for the majority, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor stated, “In order to cultivate a set of leaders with legitimacy in the eyes of the citizenry, it is necessary that the path to leadership be visibly open to talented and qualified individuals of every race and ethnicity” (Greenhouse 2003:A1). In a separate decision, the U.S. Supreme Court voted 6 to 1, invalidating the university’s affirmative action program for admission into its undergraduate program (Greenhouse 2003). In November 2006, Michigan voters approved Proposal 2, a state constitutional amendment banning consideration of race or gender in public university admissions or government hiring or contracting. Following the state’s challenge to the amendment, in 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Proposal 2, ending race-based admissions at any Michigan state schools or at any other public university in states that have ended the practice. As of 2014, 10 states have outlawed the use of affirmative action in public schools. In most of these states, there has been a decrease in the enrollment of Black and Hispanic students in their most selective colleges and universities (Liptak 2014). To achieve diversity among their student body, colleges and universities will have to focus on student socioeconomic status rather than race.

In their analysis of 1980–2015 U.S. Department of Education data, Jeremy Ashkenas, Haeyoung Park, and Adam Pearce (2017) concluded that “even after decades of affirmative action, black and Hispanic students are more underrepresented at the nation’s top colleges and universities that they were 35 years ago.” In 2015, Black students comprised 6% of college freshmen but represented 15% of college-age Americans. Hispanic students represented 22% of college-age Americans, but comprised 13% of college freshmen.

Encouraging Diversity and Inclusivity

Accelerated global migration and a resurgence of racial/ethnic conflicts characterized the close of the 20th century (Wittig and Grant-Thompson 1998) and the first two decades of the 21st century. In an effort to reduce racial/ethnic conflict and to encourage multiculturalism, researchers, educators, political and community leaders, and community members have implemented programs targeting racism and prejudice. Acknowledging that both are complex phenomena with individual, cultural, and structural components, these strategies attempt to address some or most of the components.

p.72

Lucy Nicholson/Reuters

How ethnically and racially diverse is your community? What are the largest ethnic and racial groups?

VOICES IN THE COMMUNITY

SOFIA CAMPOS

Sofia was 6 years old when she moved with her family from Peru to the United States. Sofia and her siblings quickly adjusted to their new lives in Los Angeles. It was not until she was accepted into UCLA that Sofia discovered that her family had immigrated illegally. Her mother revealed the secret when Sofia needed a Social Security number to apply for federal scholarships. Sofia explained, “I was angry at first that she hadn’t told me. But I understand why they did that. It was to protect us for as long as they could, like any parent would do with their child” (quoted in Del Barco 2012).

Although she was able to pay in-state tuition (California is one of 13 states that allow undocumented students to pay in-state tuition), she could not receive any scholarships. Sophia worked her way through college and, in five years, graduated with a double major in International Developmental Studies and Political Science.

Sofia began her activism while she was at UCLA. Inspired by her own experiences, her focus was on undocumented student rights. “That hateful language, you know, like ‘illegal, alien, wetback leach.’ People were talking about my brother, my sister, my mom, my dad. How can these people, who don’t know me at all, who don’t know the love that exists within my family, how can you be just so hateful?” (quoted in Del Barco 2012). She was a central figure in several UCLA student organizations, promoting the federal and California versions of the DREAM Act, also known as the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act. Sofia currently serves as the board chair of United We Dream, the largest network of undocumented immigrant youth. In 2014, she was enrolled in a master’s program at MIT (United We Stand 2014).

The DREAM Act was first introduced in the U.S. Congress in 2001. The DREAM Act would enact two major changes in the current law: (1) Certain immigrant students who have grown up in the United States would be permitted to apply for temporary legal status and to eventually obtain permanent legal status and qualify for U.S. citizenship if they went to college or served in the U.S. military, and (2) the federal provision that penalizes states that provide in-state tuition without regard to immigration status would be eliminated. Although the federal DREAM Act has not been passed, 18 states, including California, have passed their own versions of the act, extending in-state tuition and financial aid to undocumented college students.

Opponents of the DREAM Act argue that it is unfair to American-born and legal immigrant college students and their families. What do you think about the DREAM Act proposals? Has your state adopted a DREAM Act?

p.73