WHAT WAS THIS “Minoan” civilization that so many are so anxious to identify with Atlantis? On the island of Crete, some twenty-five centuries ago, there flourished an extraordinary culture the likes of which had never been seen before. It was rich beyond imagining, creative, artistic, influential, and enormously successful. Its architects designed splendid palaces of great size and complexity; its artists painted the walls with gorgeous frescoes; its craftsmen formed exquisite pottery; its sailors crossed the Aegean to trade with neighboring kingdoms. As unexpectedly and suddenly as it appeared, it disappeared. This civilization was named “Minoan” for King Minos* by Arthur Evans, the archaeologist who excavated the ruins on Crete at the turn of the twentieth century. The Minoans appeared mysteriously around 2500 B.C., and approximately a thousand years later disappeared completely.

The moment when human beings colonized Crete is not known, but it is believed that the first settlers were farmers who arrived some eight thousand years ago, by ship from unknown locations to the east. They used stone tools, but obsidian artifacts have also been found, indicating some sort of interaction with the volcanic islands of the Cyclades, perhaps Melos. (Crete itself is a nonvolcanic island, but it has a history of periodic earthquakes.) There is also some indication that there was contact with seafaring Egyptians of the First Dynasty, who were known to have extended their conquests as far as Palestine. They brought with them domestic animals such as cattle, sheep, and goats. These Neolithic agriculturalists lived in mud-brick houses, perhaps supported by beams hewn from trees, and we assume—at least from the lack of evidence—that they had not developed pottery-making. Later on, perhaps around 3000 B.C., they were making ceramic vases, storage jars, and drinking cups, which were often burnished and decorated. Indeed, the changes in pottery styles afford us the opportunity to identify the transition from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age, when the settlers were making vase-shaped bowls on high pedestals—the smaller ones for drinking, and the larger ones presumably for food. It was during this period that jugs with spouts also appeared, the design based on imports from Anatolia or maybe even from Libya. They buried their dead in circular tombs, and although Sinclair Hood (in his 1971 study, The Minoans) says that people “always tended to build tombs to resemble houses,” the early Cretans lived in squared-off houses, which suggests that “the custom of collective burial in circular tombs was evidently brought to Crete by immigrants or invaders from some region where round huts had been traditional,” such as Egypt.

The first-known sculptures of human beings in the round began to appear around 25,000 B.C. One of the earliest of these is the “Venus of Willendorf,” a tiny fertility figure found in a cave in Austria. During the period from 17,000 to 9000 B.C., all of Europe, from Russia to the Pyrenees, seems to have experienced a flourishing of cave painting. This period is usually referred to as the “Magdalenian,” after La Madeleine cave in the Dordogne. A few Ice Age artifacts, such as carved antler and bone implements, have been dated from approximately 12,000 B.C. Around 8000 B.C., there was a considerable settlement at Jericho in southern Palestine, and excavations in the early 1960s in Turkey revealed the existence of a densely populated settlement at Çatal Hüyük, characterized by mud-walled houses and fertility symbols in the form of bull’s heads. Çatal Hüyük dates from around 5600 B.C.; the dates for the Archaic period of Egyptian art are about 3200 to 2185 B.C. (Coincidentally, the earliest known illustration of an erupting volcano was found on a wall at Çatal Hüyük, as shown by James Mellaart 1967.)

Plato tells us unequivocally that “the citizens whose laws and whose finest achievements I will now briefly describe to you therefore lived nine thousand years ago.…” Nine thousand years before Plato was approximately 9500 B.C., and there is no archaeological evidence anywhere to suggest that humans of that time were creating anything but skin clothing, throwing sticks, and arrowheads. In a few locations in France and southern Spain, they were commemorating their accomplishments with surprisingly sophisticated cave paintings. The best-known of these are in Altamira in Spain, Lascaux in southern France, and the recently discovered, spectacular cave named for its discoverer, Jean-Marie Chauvet, at Vallon-Pont-d’Arc (also in southern France), which is believed to date from 30,000 B.C.

On the subject of Plato’s description of the advanced civilization of Atlantis, Arthur C. Clarke wrote (in The Challenge of the Sea, 1966) that “hundreds of books have been written, and men have devoted their entire lives to unraveling the truth about Atlantis. Unfortunately, most of the literature on the subject is not merely worthless—it is misleading nonsense produced by cranks.… Eleven thousand years is a very long time, but there were highly cultured races of mankind twenty or thirty thousand years ago, as is proved by the beautiful cave paintings that have been found in Spain and France.”

In an essay published in 1996, Stephen Jay Gould suggests that these artistic accomplishments should not surprise us; the painters are, after all, our ancestors, and do not differ in any substantive way from us—or from Michelangelo or Picasso, for that matter. Earlier students of Paleolithic cave painting, such as Abbé Henri Breuil and André Leroi-Gourhan, assumed that there had to be some sort of a chronological progression from the primitive to the sophisticated, and the fact that the paintings were so old meant that they had to be rudimentary. Gould wrote: “The Cro-Magnon cave painters are us—so why should their mental capacity differ from ours? We don’t regard Plato or King Tut as dumb, even though they lived a long time ago.” It therefore seems well within the realm of possibility that humans built the fabulous Atlantis that Plato said was built nine thousand years earlier; the only thing missing is a single shred of physical evidence that they did so.*Throughout the Cyclades, from about the third millennium B.C., small marble statues of women (and, occasionally, men) began to appear. The marble, it is believed, was quarried on the islands of Paros and Naxos. In most cases, the naked female figures had their arms crossed over their abdomen, and they are characterized by an elongated neck, an oval face, and a prominent nasal ridge. In his study The Cyclades in the Bronze Age, R. L. N. Barber wrote that these figures were “the most attractive of Cycladic products in the Early Bronze Age … and continue to be admired as works of art.” They were stylistically advanced for the Neolithic period in which they were made (Sinclair Hood describes one white marble figurine from Knossos as “an outstanding experiment in naturalism”), but even so, they clearly demonstrate the level of artistic achievement of Crete and the Cyclades around 2000 B.C. If Aegean craftsmen of 2000 B.C. were fashioning simple but elegant idols, what justification can there possibly be for an interpretation of Plato that suggests that a civilization predating them by seven thousand years was making “a temple of Poseidon himself, a stade in length, three hundred feet wide … covered all over with silver, except for the figures on the pediment, which were covered with gold”?

FIVE THOUSAND YEARS AGO, Europeans lived in the Bronze Age, which means that their predominant metal was that alloy of copper and tin. Around 3000 B.C., in one of the greatest revolutions in history, certain Greeks began to replace their stone adzes, axes, and chisels with tools of bronze, an alloy of copper and tin that is much stronger than stone and better able to hold an edge. Metalworking is believed to have been introduced from the East, perhaps from Palestine, and by the third millennium B.C., the inhabitants of Crete and the Cyclades were making bronze tools. (Although the Greek poet Homer was writing about events that occurred before or during the eighth century B.C., he describes warriors with obsolete bronze weapons and helmets decorated with boar’s tusks, which actually went out of use before the end of the Bronze Age.) The introduction of iron marked the end of the Bronze Age. Writing took the form of hieroglyphics or cuneiform inscriptions on clay tablets; writing on papyrus was not developed by the Egyptians until around 2500 B.C.

In The Quest for Theseus, Anne Ward includes a chapter called “Bronze Age Crete,” in which she discusses life as it was lived during the period before the flowering of the Minoan civilization. She concedes that it is difficult to reconstruct a thirty-five-hundred-year-old culture that left no written records, but examining the meager remains of the art, architecture, and artifacts, she presses on:

The houses, mostly mudbrick, were sometimes quite well designed individually, but there was no sign of anything that remotely resembled town planning. A haphazard cluster of homes was grouped together in a completely random arrangement, a characteristic which was to persist and become a dominant feature of even the most sophisticated later palaces.… The people who lived in these villages were small and slender with dark eyes and hair, typical of the long-skulled Mediterranean type. Human remains are both scarce and fragmentary, but there are signs that towards the end of the Early Bronze Age a new element arrived in Crete. This new people, taller and shorter-skulled, infiltrated in small groups along the coastline with no apparent violence. Indeed, one of the most striking features of Cretan Bronze Age history is the total absence of threat, internal or external, which was probably a powerful contributing factor to the Cretans’ cheerful, inquisitive and gregarious nature, not to mention the rapid development of their peaceful evolution.

The Paleolithic period, sometimes referred to as “prehistorical,” is usually believed to have ended around 4000 B.C., when the era we call the Neolithic began. The dates, of course, are only conjectural, but the Babylonians and the Sumerians lived in the period from approximately 3500 to 3000 B.C., and the First and Second dynasties of Egypt occurred around 2800 B.C. Zoser, the king of the Fourth Egyptian Dynasty, ruled from 2780 to 2720 B.C., and the great pyramids were built by Cheops, the king of the Fourth Dynasty who ruled from c. 2700 to 2675 B.C. The “Dynasty of the Pharaohs” lasted for almost two thousand years, from 2200 B.C. to 525 B.C., during which time the Egyptians developed hieroglyphic pictograms, and the Minoans in Crete invented the primitive Greek alphabet. Between 1500 and 1000 B.C., Moses is said to have received the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. Around 1020 B.C., Saul became the first king of Israel, and was defeated by the Philistines in 1002 B.C. King David succeeded him, and ascended to the throne of the Kingdom of Judah and Israel around the year 1000 B.C., and he was succeeded by his son Solomon in 960. The Neolithic settlements in Crete are dated between 3000 and 2500 B.C., and we believe that the snake and the bull were worshiped by the Minoans in Crete at about the same time (2500 to 2000 B.C.) that the Egyptians believed in Isis and Osiris, deities in the cult of resurrection from the dead. Around 1900 B.C., the first palace of Minos was built at Knossos in Crete, and archaeological evidence has revealed that the Minoans had ventilation systems in their multilevel dwellings, as well as bathrooms with running water. The resurrected murals on the walls of Knossos also show that religious rites took place at this time, often associated with a cult of bull worship. As J. L. Caskey, an American archaeologist, wrote, “Human life and society blossomed at the palaces, where, as many have remarked, elegance and delicacy reached levels that had been quite unknown before and were scarcely to be seen again in Europe for three thousand years.”

Unlike the contemporaneous Egyptians of the Early and Middle kingdoms, who left answers in the form of hieroglyphic inscriptions, poems, and chronicles, the inhabitants of Crete left only the remains of mysterious edifices, and unanswered, tantalizing questions. Who built the great palace at Knossos, with its gracefully tapered columns, its labyrinthine corridors, its “bull-dancing” frescoes, its wasp-waisted courtesans? Who was the architect of this splendid palace, whose innovations were barely matched by the more “advanced” civilizations of Egypt, Sumer, and the Indus Valley? What happened to annihilate the civilization that had arisen (and so dramatically fallen) on this isolated island in the middle of the Mediterranean? And what does Crete have to do with Atlantis?

CRETE IS the largest of the Greek islands, 152 miles long and 35 miles across at its widest point. There is a mountain ridge that runs nearly the length of the island on its east-west axis. By 1500 B.C., Crete had become the dominant sea power in the eastern and central Mediterranean: a seat of high civilization, with commodious palaces, fine craftsmanship, and writing. It was the first to boast such accomplishments in Europe—the fact that it occurred on an island made it even more extraordinary—and later, the mainland Greeks adapted the Cretan civilization to develop their own.

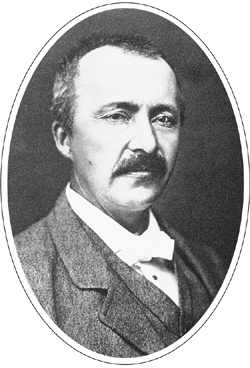

Among the first excavators to visit the hard, dry soil of Crete was the German businessman Heinrich Schliemann (1822–1890), one of the most celebrated archaeologists of all time. After making his fortune in international trade, Schliemann “retired” to pursue his passion for archaeology. He was an astonishing polyglot, and in addition to his native German, he taught himself English, French, Dutch, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Swedish, Polish, Russian, and Greek, ancient and modern. (Of his ancient Greek—which he claimed to have mastered in three months—he commented, “I have thrown myself so wholly into the study of Plato that, if he were to receive a letter from me six weeks hence, he would be bound to understand it.”) There being no other way to accomplish it, the brilliant, eccentric Schliemann also taught himself archaeology.

HEINRICH SCHLIEMANN BELIEVED that the Iliad and the Odyssey were true, and, accordingly, looked for the fabled city of Troy where Homer said it was—and found it. (illustration credit 5.1)

The idea that Troy was to be found under the hill of Hissarlik did not originate with Schliemann. It had been proposed some fifty years earlier by a man named Charles MacLaren, who wrote a book about it in 1822—the year Schliemann was born. MacLaren’s ideas (published in A Dissertation on the Topography of the Plains of Troy) were theoretical and literary, and not at all archeological. Because he believed that Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey were fact rather than poetic legends, Schliemann dug for Troy where he believed Homer (and MacLaren) had located it, in what is now western Turkey. Others felt that it had been located on the site of a village called Bunarbashi, but when Schliemann tried to run around it—as Achilles had done while chasing Hector—he found that it was impossible because the village was situated at the foot of a ridge. He dug instead at Hissarlik, close enough to the coast so that the Homeric heroes could travel back and forth several times daily. In 1872, he confounded the skeptics by finding stone walls, which he described as “six feet thick and of most wonderful construction,” and beneath the first layer, more walls. Reasoning that Troy would be at the bottom, he and his crew of one hundred twenty Turkish workers dug ruthlessly, destroying almost everything in their path. (In his haste to get to the bottom, and thus to the earliest settlement, Schliemann raced past the actual Troy, which later archaeologists would identify.) By the following year, having cleared away and destroyed a mountain of invaluable stratigraphic and archaeological evidence, Schliemann hit pay dirt. In the wall of a building he had already designated as Priam’s palace, he found a spectacular trove of golden objects: elaborately wrought necklaces and earrings, diadems, cups, ceremonial drinking vessels, weapons, shields—in all, more than ten thousand items. He and his Greek wife Sophia packed the stuff up and smuggled it to his house in Athens, where he kept it on prominent display.* Naturally, he believed that these items dated from the Trojan War (c. 1190 B.C.), but later scholars proved that their date was almost a thousand years earlier.

Schliemann then proceeded to Mycenae, where, again against all expectations, he announced that he had found an even richer treasure: the tomb of King Agamemnon and his wife Clytemnestra. This time, he relied upon the writings of the Greek travel writer Pausanias, who had visited the area around 170 A.D. and had described what he saw there. “Still,” he wrote, “there are parts of the ring-wall left, including the gate with the lions standing on it.” The “Lion Gate” was visible to Schliemann some seventeen hundred years later, but where later writers had assumed that the graves of Agamemnon and his murdered friends would be found outside the walls of the citadel, Schliemann took Pausanias at his word and looked inside. (Pausanias wrote, “Clytemnestra and Aigisthos were buried a little further from the wall. They were not fit to lie inside, where Agamemnon and the men murdered with him are lying.”) He found the graves, which contained another fabulous treasure, including gold breastplates and gold burial masks, one of which was of a bearded prince. Schliemann immediately cabled the king of Greece: “I have gazed upon the face of Agamemnon.” They were indeed royal graves, but of richly dressed persons who had lived some four hundred years before Agamemnon, but it hardly mattered. As the pseudonymous C. W. Ceram (actually Kurt W. Marek, a German writer on subjects archaeological) wrote in Gods, Graves, and Scholars:

The important thing was that Schliemann had taken a second great step into the lost world of prehistory. Again he had proved Homer’s worth as historian. He had unearthed treasures—treasures in a strictly archaeological as well as material sense—which provided valuable insight into the matrix of our culture. “It is an entirely new and unexpected world,” Schliemann wrote, “that I am discovering in archaeology.”*

Pumice from the Aegean island of Santorini was an important element in the 1866–69 building of the Suez Canal, since this material, known as pozzulana, was needed for the manufacture of water-resistant cement required for the harbor installations. In 1866, only a few months after the building had commenced, the long-dormant volcano on the island erupted. Among the visitors who came to observe the eruption was the French volcanologist Ferdinand Fouqué, who wrote a classic paper on the eruption (Santorini et ses éruptions), and when he interviewed some of the locals, he discovered that they had been collecting small artifacts from the slopes of the volcano for years. He saw some gold rings and learned that there were two tombs, long since plundered. Under twenty-six feet of pumice, Fouqué encountered a crypt with a central pillar made of blocks of lava, a human skeleton, blades made of obsidian, and pottery shards that were decorated in a style that neither he nor anyone else was able to identify. He concluded that a volcanic eruption of c. 2000 B.C. had divided the island into two parts, now known as Thera and Therasia, but the presence of the gold and potsherds suggested to him that there might be something of interest buried under the pumice.

Because he was not an archaeologist, Fouqué asked the French Archaeological School at Athens to provide somebody who could perform proper excavations. They sent Henri Mamet and Henri Gorceix, who dug under a vineyard and discovered various rooms that contained pottery, tools, lamps, and a quantity of stored food, including identifiable barley, rye, chickpeas, and the bones of rabbits, sheep, goats, a dog, a cat, and a donkey. They also found walls painted with designs of irises and lilies, but many of the paintings were charred. Messrs. Mamet and Gorceix worried that the fragile walls of this underground sanctuary would crumble, so they removed the pottery pieces, which were eventually assembled into more than a hundred vases, decorated in a completely unfamiliar style. During the last decade of the nineteenth century, a team of German archaeologists led by Baron Hiller von Gaertringen dug in the ruins of ancient Thera at Mesa Vouno (on Santorini), and also made some tentative trenches in the vicinity of Akrotiri.

The French findings on Akrotiri led Schliemann to believe that there might have been an Aegean civilization earlier than the Mycenaean, perhaps in Crete. He made one visit to the island but could not agree on the price of the land he wished to excavate, and left without turning a stone. (In those freebooting archaeological days, diggers often bought the land outright, so everything they found belonged to them.) When Arthur Evans met with Schliemann in Athens in 1883, he was less interested in the Gold of Troy than he was in Greek coins and seals. (Evans was curator of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford from 1884 to 1909, and went on to become Extraordinary Professor of Prehistoric Archaeology in 1909.) He went to look for the coins and seals on Crete.

Like Schliemann, Arthur John Evans, born in 1851 in Hertfordshire, is credited with one of the most important archaeological discoveries of all time. But unlike Schliemann, who was self-taught, Evans was trained as an archaeologist, and he had already worked in Sicily and Britain. At the age of forty-three, Evans was lured to Crete because of his interest in Greek numismatics. The story is told that he was extremely nearsighted, and a reluctant wearer of glasses. He could see small objects held a few inches from his eyes in extraordinary detail, and the hieroglyphics on the sealstones from Crete were sharp and clear to him. In Crete, he found that nursing mothers wore these inscribed stones, now called galopetras (“milk stones”), around their necks to ensure the health of their babies. Evans bought five acres in Crete, and working with D. G. Hogarth and Duncan Mackenzie, on his own land he unearthed the fabulous palace of Knossos. The hill on which it lies turned out to be man-made; it consisted of an accumulation of building levels and occupation extending back some four thousand years before the palace. It was evident that Knossos was an important cultural capital, and because the intricate ground plan of the palace suggested the myth of the Labyrinth associated with the legendary King Minos, Evans bestowed the name “Minoan” on this sophisticated Bronze Age civilization.

In his History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides wrote, “The first person known to us by tradition as having established a navy is Minos. He made himself master of what is now the Hellenic sea, and ruled over the Cyclades, into most of which he sent the first colonies.” Until Evans began his dig on Crete and unearthed a completely unexpected civilization, the tales of King Minos (and the associated legends of Theseus and the Minotaur) were assumed to be part of the rich tapestry of Greek mythology. “Evans promptly announced to the world,” wrote Ceram, “that he had found the palace of Minos, son of Zeus, father of Ariadne and Phaedra, master of the Labyrinth, and of the terrible monster, the Minotaur, that it housed.”

The name of Theseus is inextricably bound to the lore of Knossos. In the mythology of the Greeks, he was the son of Aethra and Aegeus, who had visited Aethra in the form of a bull. (Poseidon was also supposed to have visited Aethra on the night of the conception of Theseus, so his paternity is in doubt). His exploits, which are similar to those of Hercules, include the slaying of Procrustes (he of the bed) and his adventures on Crete. He volunteered to take the place of one of the young men who was assigned to bring tribute to Minos, but instead of offering himself up for sacrifice to the Minotaur, he set out to slaughter the half-man, half-bull. Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos, fell in love with him and gave him the ball of twine that he played out as he searched the Labyrinth for the Minotaur. Theseus killed the Minotaur, followed the string out of the Labyrinth, and headed for home with Ariadne and her sister Phaedra. He abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos, where she was consoled by Dionysus (Bacchus), who gave her a crown of seven stars which became a constellation after her death. In his haste to return home, Theseus forgot to change his sail from black to white, and his father, Aegeus, thinking he was dead, threw himself into the sea, which sea became known as the Aegean.

In Man, Myth, and Monument, classical scholar Marianne Nichols wrote that after Theseus had killed the Minotaur and was returning with its head to King Minos, “his patron Poseidon sent a great earthquake that destroyed the palace and its inhabitants, allowing only Theseus and Ariadne to escape unharmed.” Even though this “earthquake” is not usually incorporated into the myth of Theseus, Nichols’s mention of it adds a tantalizing note to the complex interweaving of the stories of Knossos and Atlantis.

Although the name of Arthur Evans is indelibly associated with the excavation of Knossos, he was not the first archaeologist to dig there. From December 1878 to February 1879, Minos Kalokairinos had made “soundings” at Kephala, in what would eventually be identified as the west wing of the palace of Knossos, and he had collected storage jars (pithoi) that he kept in his house and allowed various scholars to examine. In 1881, an American journalist named W. J. Stillman visited the site and reported to the Archaeological Institute of America that he had examined ancient walls made of gigantic blocks of stone, and that they might have been part of the mythological Labyrinth. Three months into the new century, on March 23, 1900, under Evans’s nearsighted but watchful eye, the first shovelful of earth was turned at Kephala. It proved to be a triumph for Evans but nearly a disaster for archaeology. In The Find of a Lifetime, her biography of Evans, Sylvia Horwitz wrote:

Evans, one of the pioneers in archaeology, was unfamiliar with all the modern skills of excavation. He did not know today’s accepted techniques of making a deep cut through all the strata from the surface down to virgin soil. Of clearing stratum by stratum horizontally. Of leaving standing sections at frequent intervals from the surface down to serve as “control points,” whereby one could relate structures or disturbances to their proper strata.

By the second day of his excavations at Knossos, Evans’s workers had uncovered the remains of a house with fragments of wall paintings, and the next day they found walls blackened by fire and the rims of upright pithoi buried in the rubble. By the end of a week, he had discovered the first tablet with writing on it, and within a few days, hundreds more.* Squinting at the tablets, he recognized two different kinds of inscribed writing, which he named “Linear A” and “Linear B”—about which more later. In April, on the floor of what appeared to be a hall or corridor, a workman uncovered two large fragments of a fresco that depicted a life-size figure carrying a rhyton. In his notes, Evans wrote that it was “by far the most remarkable figure of the Mycenaean Age that has yet come to light.” (At this early stage, he had not yet given the name “Minoan” to this ancient civilization.)

On April 13, workmen began to uncover the high back of a carved gypsum chair, located in a chamber that appeared to have had paintings of winged griffins on the walls. Evans decided that the chair was a throne, the room was a throne room, and that its original occupant had been King Minos. He wrote, “The elaborate decoration, the stately aloofness, superior size and elevation of the gypsum seat sufficiently declare it a throne room,” and in an article he submitted to the Times of London, he wrote:

Crete was in remote times the home of a highly-developed culture which vanished before the dawn of history.… [A]mong the prehistoric cities of Crete, Knossos, the capital of Minos, is indicated by legend as holding the foremost place. Here the great law-giver promulgated his famous institutions … here was established a maritime empire … suppressing piracy, conquering the islands of the Archipelago, and imposing a tribute on subjected Athens. Here Daedalos constructed the Labyrinth, the den of the Minotaur, and fashioned the wings—perhaps the sails—with which Icarus took flight over the Aegean.

Also during that momentous first season, workers unearthed a life-size bull’s head (without the horns), which Evans described as “perhaps the effigy of the beautiful animal that won the heart of Pasiphaë, or of the equally famous quadruped that transported Europa to Crete.” Evans believed it was probably associated with the bull games, but other fragments found near it included rocks, olive branches, and part of a woman’s leg, which suggest a bull hunt. For a sculpture dated around 1600 B.C., it is truly remarkable. The animal’s eyes are wide and its mouth is open, just like those of the bulls on the famous gold cups found at Vapheio (on the Greek mainland near Sparta), which were unquestionably of Cretan origin. (In The Bull of Minos, Leonard Cottrell wrote that “they were thought at first to be ‘Mycenaean,’ but after Evans’s Knossian finds they were recognized to be Minoan in style, probably imported from Crete, or alternatively produced on the mainland by Cretan artists.”) The two cups, found together in a tholos tomb twenty years before Evans began to dig at Knossos, graphically depicted the activities involved in the capture of wild bulls. On one cup, bulls are being driven into nets slung between two olive trees, and one bull has thrown a would-be captor to the ground while a girl grapples with it in an attempt to save her compatriot. The other cup shows that the Minoans were not above subtle subterfuge: they enticed the bull into the nets by using a receptive cow as a lure. As Evans described the scene: “The bull’s treacherous companion engages him in amorous converse, to which her raised tail shows the sexual reaction. The extraordinary human expressiveness of the two heads as they turn to each other is very characteristic of the Minoan artistic spirit.” The human figures are also magnificently configured in relief, and the man who captures one of the bulls by throwing a loop around its hind leg is probably the finest surviving picture of a Minoan male.

FROM THE TITLE PAGE of the fund-raising-appeal brochure for the “Cretan Exploration Fund” in 1900. In the photograph, the throne room is being excavated. (illustration credit 5.2)

THE LIFE-SIZE bas-relief of a bull’s head found in the north portico of the palace of Knossos. The original is now in the Herakleion Museum; a reconstruction greets modern visitors to Knossos. (illustration credit 5.3)

In The Palaces of Crete, art historian J. W. Graham described the material of the Minoan palaces as smoothly dressed blocks of limestone, but the provincial buildings were made of unworked gray limestone, plastered over. Houses were usually two stories high, and the palaces consisted of three, with extensive colonnades and broad staircases. There were sophisticated refinements everywhere: a drainage system of terra-cotta pipes at Knossos, walls faced with thin sheets of gypsum (now known as alabaster), light wells, what appear to be bathtubs, courtyards, and, certainly the most surprising of all, elaborate wall paintings that depict (we think) the life and times of the Minoans. (Their only written records are in the still-undecipherable Linear A, so we have to rely entirely on the remains of the crumbled walls, broken pottery, and reconstituted frescoes for clues as to how these people lived some thirty-five hundred years ago.*)

THE GOLD “Vapheio cups” were not found on Crete, but they are obviously Minoan. They depict various scenes of the capture of wild bulls, including this one of a muscular young man throwing a loop around the animal’s hind leg. (illustration credit 5.4)

Throughout the ruins of Knossos, brightly colored pieces of plaster continued to turn up—fragments of the frescoes with which the Minoans brightened their walls. At first, Evans tried to reassemble the shattered paintings, but it was not long before he decided to reconstruct them. He commissioned Emil Gilliéron, a Swiss artist who had been working at the French Institute of Athens, to repaint the frescoes. It must be borne in mind that this was—until Evans began uncovering it—a completely unknown civilization, so there were no precedents or examples whatsoever indicating what the people looked like, what they wore, or what they might have been portrayed as doing. With his son Edouard, Emil Gilliéron worked for nearly a decade alongside Evans at Knossos. Together they resurrected an entire palaceful of people. In his enthusiasm, Evans (and probably Gilliéron père et fils as well) took enormous liberties when filling in the missing pieces, and even today, visitors to the museum at Herakleion in Crete marvel at the reconstructions, where whole figures were completed on the basis of a head, an eye, or a foot. (The reconstructed originals are in Herakleion; the paintings on the walls at Knossos are copies of the reconstructions, containing no Minoan fragments.) One of their more flagrant errors occurred with the “saffron gatherer,” where they decided to fill in the missing pieces of a blue-skinned “boy,” until a blue tail was found, identifying the figure as a monkey.

“Everywhere the bull!” wrote Evans. Its importance as a symbol of fertility and power can be seen in the architecture (where huge stylized horns form an important element); in the artifacts found in the rubble (plaques, cups, and jewelry decorated with bulls); and in the spectacular frescoes that depict the bull-dancing (also called “bull-leaping,” or even “bull-fighting”), where acrobats vault over the horns of a charging bull in one of the great mysteries of ancient times.

The “Toreador Fresco” is at the same time the most important and the most enigmatic of all the Minoan wall decorations. Found in fragments on the floor of a room in the east wing off the central court, this fresco was reconstructed by Evans and Gilliéron to show an activity that has defied interpretation since its discovery. It shows three youths, two females (identifiable by their white skin color), and a male (red skin color) who is apparently leaping over a great spotted bull. The women are positioned at either end of the fresco (and at either end of the bull); the one on the left is grasping the horns; the one on the right has her arms outstretched, waiting to catch the “vaulter.” The reconstructed fresco is now in the museum in Herakleion, and since a large proportion of the original pieces—particularly the woman on the right, the vaulter, and the bull—are present, it would appear that the reconstruction is fairly accurate. However, even if the fresco had been preserved in its entirety, it would still present an almost impossible mystery. Even Arthur Evans, so quick to provide interpretations based on minimal evidence, was baffled. He traveled to Madrid to see if he could find a connection between Spanish bullfighting and the Minoan frescoes; he even investigated the American rodeo sport of steer-wrestling to see if he could make some comparison. Frustrated and unable to resolve the problem, he could only describe the fresco. In The Palace of Minos, he wrote:

PROBABLY THE MOST FAMOUS—and certainly the most misunderstood—of all Minoan frescoes, the “bull-leapers” shows three youths performing some sort of ritual acrobatics with a great spotted bull. Exactly what they are doing has never been satisfactorily explained. (illustration credit 5.5)

In the design … the girl acrobat in front seizes the horns of a coursing bull at full gallop, one of which seems to run under her left armpit. The object of her grip … clearly seems to be to gain a purchase for a backward somersault over the animal’s back, such as is being performed by the boy. The second female performer behind stretches out both her hands as if to catch the flying figure or at least steady him when he comes to earth the right way up.

His successor J. D. S. Pendlebury also tried to solve the mystery, and wrote:

Another [interpretation] may have been a bull-fight, of which the action is well-known from a later painted panel at Knossos. At this one-sided game, in which girls as well as boys performed, the acrobat or victim stood in front of a charging bull, grasped its horns, and turned a somersault along its back, an athletic feat which seems to be impossible. If the performers were expected to be killed, the ritual would form a human sacrifice, of which there is no other trace on Crete. The bull was certainly a sacred animal, and itself a principal victim of sacrifice.

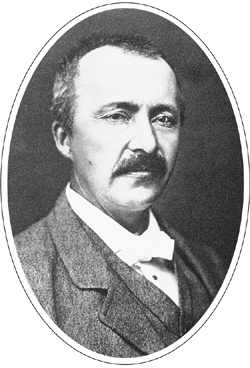

On a seal found at Priene (in Anatolia, but the seal is undoubtedly Minoan), there is another representation of a bull and a person that is considerably smaller than the “Toreador Fresco” but no less enigmatic. (The fresco is approximately five feet long; the seal is about the size of a thumbnail.) This is the seal that Evans described as “the finest combination of powerful execution with minute detail to be found, perhaps, in the whole range of the Minoan gemengraver’s Art.” It shows a powerfully muscled bull with its forelegs up on a large rectangular object, and a man who seems to be leaping headfirst onto the animal’s head. “The common but hardly possible explanation of this scene,” writes James Graham, “is that it shows a man capturing a bull which he had surprised drinking from a tank. Surely no bull would drink in such a fashion, nor would a Minoan artist have so represented him!” Graham (and other authors) noted that the pattern of latticed lines that follow the four sides of the rectangle and also cross it at a diagonal is repeated in only one other known instance: on the rear face of two niches at the north end of the central court. Graham proposes to resolve the mystery of the seal by conjuring up a second. He posits that a mysterious two-step platform to nowhere (also in the central court) represents “one of the doubtless numerous maneuvers which were devised to lend variety and interest to the bull games … in which the acrobat, cornered, whether intentionally or not, in this blind angle of the court, quickly stepped up on this platform and, at the right moment, as the bull perhaps succeeded in getting his forefeet on the narrow end of the first step, bounded upon its back and thence to the ground behind the bull, safe from his apparent impasse.” This seems a rather strained explanation, with a large measure of speculation, but until a better one appears, it will have to do.

MINOAN BRONZE SCULPTURE of a bull and an acrobat, found near the town of Rethymnon, on Crete. The figure of the acrobat (whose legs are missing) is attached to the bull by his long hair. (illustration credit 5.6)

A MINOAN SEALSTONE that shows a bull engaged in an ambiguous act involving a pair of mysteriously disembodied legs above its head, and an equally enigmatic square object decorated with lozenges (illustration credit 5.7)

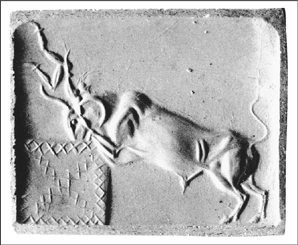

Any explication that is developed four thousand years after the fact and relies upon fragmented pieces of evidence can only be conjectural, but it seems a bit of a stretch to see the bull-dancing as a religious demonstration involving wild animals and death-wish acrobats. It is more likely that the enterprise was a sort of circus act, in which the bull was trained—or at least tamed—so that the acrobats could leap over it. They might not always have been successful.* Whatever the significance of the bull or the bull-dancers to the Minoans, their appearance was not restricted to wall paintings. Men (or women) and bulls are represented on seals, on offering cups, and on perhaps the finest extant Cretan bronze, which shows an acrobat vaulting over the back of a bull. There is also a graceful ivory figure of a bull-leaper, dating from about 1600 B.C., but it is even less useful than the frescoes in determining what actually happened, since there is no accompanying bull.

It is difficult to understand those who equate Plato’s descriptions of bull capture and sacrifice with the Minoan practice of bull-leaping. In the one instance, the bull is brought to a sacrificial altar and its throat cut; in the other, it is used—very much alive—for what appear to be ceremonial gymnastics. Plato probably included bull sacrifice because it was an important part of ceremonial practice in Greece of the fourth century, and it is therefore likely that he would have included it in his Atlantis story.

Because it was totally unfortified—unusual for a capital in those battle-some days—Knossos required some means of defense, and nautical relics suggest that the island city was protected by a massive fleet. Pottery shards showing all sorts of marine creatures—octopuses, sea urchins, starfish, fishes, dolphins—strongly suggest a marine civilization. (The seafaring propensities of the Minoans also made it possible for them to colonize other islands, such as Strongyle [Santorini], seventy-five miles to the north.)

IN Crete and Mycenae, Spyridon Marinatos calls this ivory figure of an acrobat (probably a bull-leaper) “a small masterpiece,” and writes, “The movement, bold pose and working of detail all command admiration. Fingers, fingernails, veins and muscles are modeled or incised with precision.…” (illustration credit 5.8)

The most spectacular elements in the astonishing architectural history of Crete are the palaces, and the most spectacular of these was Knossos. Built on the hill of Kephala, revealed by archaeologists to have been the site of an earlier Neolithic settlement, the palace was built around 1900 B.C., in the period known as “Middle Minoan IB” in Evans’s chronology. It thrived for two centuries, was destroyed, and then was rebuilt; around 1375, when it was in the hands of the Mycenaean conquerors, it was completely and finally demolished.

During the season of 1901, Evans and his coworkers decided that in order to continue digging, they would have to begin an extensive program of supporting the crumbling walls, adding beams and columns where they had identified the remains, and, in general, reconstructing parts of the palace of Knossos, which had lain buried under the hill of Kephala for more than three thousand years. It was a controversial decision, and one for which Evans has received much criticism, but it seemed to him that such measures were necessary to keep the whole dig from collapsing or turning to mud in the spring rains. In The Bull of Minos, Cottrell says that “unreflecting visitors to Knossos have sometimes criticized Evans for his ‘reinforced concrete restoration.’ Such criticisms are unintelligent; he had no alternative,” and Pendlebury wrote, “Without restoration the Palace would be a meaningless heap of ruins, the more so because the gypsum stone, of which most of the paving slabs as well as the column bases and door-jambs are made, melts like sugar under the action of rain, and would eventually disappear completely.”

THE RESTORED “West Bastion” of the north entrance passage at Knossos. Under the overhang is a copy of the relief of the bull shown in the illustration on this page. The columns, reconstructed by Arthur Evans, have been painted brick red. (illustration credit 5.9)

Now partially uncovered and partially reconstructed, this is actually the second palace of Knossos, built on top of the ruins of its predecessor. It is therefore referred to as the “New Palace.” The building is roughly square in plan, approximately 150 meters (almost 500 feet) on a side, with an immense central court. The palace itself covers an area of some 22,000 square meters (26,312 square yards) and is constructed of stone, wood, and clay. (Eventually, the palace would be shown to include more than a thousand rooms.)

The plan, such as it was, appears to consist of multistoried royal apartments, storerooms, religious shrines, great halls, capacious staircases, rooms, and courtyards randomly added to the central court, which is about 50 yards long and half as wide. (It was the mazelike nature of these rooms that inspired Evans to liken it to the Labyrinth.) The rooms were connected by light wells—small courtyards that allowed light to enter roofed-over areas. This meant that no section was ever in darkness, no matter how intricate the plan. At its greatest height, the palace was five stories tall, but the roofs at every level were flat, which facilitated its organic architectural growth. The upper floors were supported by wooden columns, wider at the top than at the bottom and resting on gypsum bases. (It is said that this column design was modeled on tree trunks once used to support buildings, placed upside down so they would not take root and sprout again.) Although no columns have survived, Evans reconstructed the new ones at Knossos on the basis of a fresco fragment that showed them to be dark red, with a capital that consisted of a two-tiered cushion decorated with double axes. The walls were made of rubble masonry or mud brick, framed with horizontal timbers, and plastered.

Plaster walls were a natural surface for wall paintings, and the frescoes (paint applied directly to wet plaster) at Knossos are among the most spectacular treasures of the ancient world. Early Minoan houses on Crete were also plastered, and the walls painted red. Then followed repeated ornamental designs, but by the Middle to Late Minoan periods, from 1700 to 1500 B.C., the art of fresco painting had reached unprecedented heights. “The style,” wrote Reynold Higgins, “is the first truly naturalistic style to be found in European, or indeed, in any art.” Only a few of the frescoes at Knossos are more than fragments, but painstaking restoration has provided a suggestion of the missing elements in these paintings of processionals and ceremonial or religious festivals. There are depictions of flowers, and a full menagerie of lifelike studies of birds, monkeys, deer, a cat stalking a pheasant, and a leaping deer. Seafaring people on an island in the Mediterranean would be more than a little familiar with marine life, and there are various fishes and an occasional dolphin.

In the light-welled room that he dubbed the “Queen’s Megaron,” Evans unearthed low benches (“to be best in keeping with female occupants,” he wrote) and fragments of frescoes that were eventually reconstituted as the famous “Dolphin Frieze” and the dancer with the flowing hair. The dolphins (identified as Stenella caeruleoalba, the striped dolphin) are gracefully deployed in a scene that includes several small fishes. Unfortunately, only a few pieces of this fresco were preserved, so much of the arrangement is conjectural. The same must be said for the twirling “dancer,” whose loose hair seems to be lifted by her energetic movements, but, of course, we can only guess what the rest of the fresco looked like. Perhaps it showed a dance like the one described in book 18 of the Iliad:

The god depicted a dancing floor like the one that Daedalus designed in the spacious town of Cnossus for Ariadne of the lovely locks. Youths and maidens were dancing on it with their hands on one another’s waists, the girls garlanded in fine linen, the men in finely woven tunics showing the faint gleam of oil, and with daggers of gold hanging from their silver belts. Here they ran lightly round, circling as smoothly as the wheel of a potter when he sits and spins it with his hands; and there they ran in lines to meet each other. A large crowd stood round enjoying the dance while a minstrel sang divinely to the lyre and two acrobats, keeping time with his music, cart-wheeled in and out among the people.

Or perhaps, as Jacquetta Hawkes suggests, the dancers took drugs. In her discussion of the dancers “whirling at speed,” she says, “It is quite likely that, as today [Hawkes’s Dawn of the Gods was published in 1968], drugs were sometimes taken to encourage a sense of revelation, possession and trance. On one seal the seated goddess is holding three poppy seed-heads, and in a late figurine she is wearing three seed-heads, cut as for the extraction of opium, set in a crown above her forehead. The growing of opium poppies has a very long history in Anatolia.”

THE CELEBRATED “Dolphin Frieze” in the “Queen’s Megaron” in the palace of Knossos. These remarkably lifelike animals have been identified as striped dolphins, otherwise known as Stenella caeruleoalba. The grille closes off a doorway leading to a staircase to the upper floor. (illustration credit 5.10)

We know frustratingly little about the other activities of the Minoans. (Our inability to translate the tablets inscribed in Linear A has greatly contributed to our ignorance.) Men and women are depicted in the frescoes, and there are a few small sculptures that have enabled historians and archaeologists to make educated guesses about life in and around the palaces of Crete. As a rule, ordinary people were not the subjects of commemorative creative arts, so what little evidence there is depicts what we assume are royalty or deities. (An exception is the “harvesters’ vase” from Hagia Triada, which shows ordinary villagers returning from [or going to] the fields.) A bas-relief of a standing man is known as the “priest-king” (also called the “Prince of the Lilies”) because he wears a high crown of lilies and peacock feathers on his head and a necklace of flowers around his neck. In his outstretched left hand, he holds the end of a rope, and we are left to wonder what sort of creature he is leading. A bull? A griffin? A sphinx? That is the way the fragments have been reconstructed, and the “prince” is one of the best-known and best-loved of all Minoan frescoes.

THE “PRIEST-KING” of Knossos, long believed to represent the ideal of Minoan royalty, has been reassessed, and is now thought to consist of parts of three different figures. (illustration credit 5.11)

Female figures abound, often priestesses or goddesses, but there are also highborn women seen at various rites or sporting events, such as the Knossos fresco that shows a group of gossiping women watching some sort of event—perhaps the bull-dancing. These elaborately coiffed ladies are among the Parisiennes, but not even the courtesans of nineteenth-century Paris would have appeared bare-breasted in public, as did the women of Knossos. Whatever their state of dishabille, women played an important role in Minoan Crete, since they appear in wall paintings, vases, and sculpture, and can be seen engaging in virtually all activities, from spectating and dancing to hunting expeditions and bull-leaping. (So far, no women boxers have been found, but there is a sealstone from Knossos that shows a woman [a goddess?] with a sword in hand.) Moreover, Minoan women were beautifully dressed, with elaborate belts that cinched in tiny waists, and heavy, flounced skirts. In many of the frescoes, their hair was intricately styled, with long curls that reached to the shoulders, and shorter curls at the forehead, often held back by a headband or a small, beret-like hat.

By and large, the men of Knossos were dressed more simply than the women, with a short girdle or loincloth that emphasized their lithe, muscular bodies. They are often shown participating in some sport—wrestling, boxing, jumping, running—and, of course, the bull-dancers were often, but not always, male. (The “boxers” and the “fishermen” of Akrotiri are among the most dramatic representations of Minoan youths.)*

One of the strangest interpretations of the palace at Knossos was propounded by a German paleontologist and geologist named H. G. Wunderlich. In his 1974 The Secret of Crete, Wunderlich argued that Arthur Evans was completely wrong about the Minoans: the palace was not occupied by Minoan royalty à la the British system, and the villas scattered around were not for nobility descended from the king. The entire complex, he opined, was “a city of the dead; an elaborate necropolis where a powerful cult practiced elaborate burial rites, sacrifices, and ritual games.” Although Wunderlich’s interpretation is bizarre, he does point out some unusual features of the palace that give one pause. For example, the principal building material was gypsum, a stone so soft and friable that it seems highly unsuitable for a building inhabited by hundreds of people. Also, there were so many windowless rooms; alabaster steps that seem unworn; “bathrooms” with drainage holes but no pipes; and row after row of food-storage vessels, but no kitchen. He further suggests that Linear B will remain undeciphered as long as archaeologists seek a prosaic explanation. “The tablets,” he writes, “were shorthand notes given to the dead to take with them into the hereafter. In some cases they were messages to the dead of the mortuary palace. Possibly the Phaistos Disk was one of these telegrams to the ‘living dead.’ ” (In her life of Arthur Evans, Sylvia Horwitz said that Wunderlich’s book “showed what problems besides dating an archaeologist can come up against.”)

MICHAEL VENTRIS, who first realized that the Linear B inscriptions found at Knossos were actually an early form of Greek (illustration credit 5.12)

Early in the excavations at Knossos, Evans was shown several faience plaques with incised writing on them. Down to the fifteenth century, Crete was occupied by people who wrote a language that is not identifiable, but certainly was not Greek. Cretan writing, a syllabic script known as “Linear A,” was inscribed onto clay tablets, vases, and occasionally carved into stone. Evans devoted himself to the translation of Linear A, but he died without breaking the code. (“Ironically,” wrote Sylvia Horwitz, “in a lifetime of pursuing his own ends, only one achievement eluded him: the decipherment of Minoan script.”) Indeed, many scholars have died without breaking the code, since Linear A is still a complete mystery.*

Sometime around 1400 B.C., this writing was replaced by another, related form, known as “Linear B,” which appears almost exclusively on clay tablets. Linear B was also believed to be undecipherable, but in 1952, the British architect and linguist Michael Ventris (working with the classicist John Chadwick) showed that it was actually used to write an early form of Greek (as opposed to Cretan)—a discovery that changed the interpretation of Minoan archaeology. (Ventris, whose genius solved the Linear B conundrum, was killed in 1956 in an automobile accident, when he was thirty-four years old.) Were there Greeks at Knossos before the Cretans? Evidently there were, which meant that the first flowering of Minoan culture, so beloved by Arthur Evans, was actually the earliest stage in the history of Greek art. Most of the tablets written in the Linear B script are, according to Chadwick, “deplorably dull: long lists of names, records of livestock, grain and other produce,” but even so, they give us a glimpse into a civilization whose history is very poorly understood, but whose importance cannot be overrated.

AT HIS HOME in Crete (which he called “Villa Ariadne,” after the daughter of King Minos), Evans was reading in bed in the evening of June 26, 1926, when he was nearly thrown onto the floor. Objects and books fell from their places as the earth beneath him trembled. He ran out to check his excavations at Knossos. They had been propped up with steel pillars, and remained intact. But then and there the thought occurred to him that the abrupt end of the Minoan civilization had been accomplished by an earthquake. (Evans knew of Fouqué’s excavations at Santorini and his theory that the volcanic eruption at Santorini had buried the settlements there.) “Most archaeologists,” wrote Ceram in 1951, “do not subscribe to this interpretation. A later day may clear up the mystery.”

We do not know what caused the downfall and disappearance of the Minoan civilization, but we do know that a series of earthquakes in Crete wreaked havoc on the palaces, and that the island of Thera blew up, bringing down the Minoan stronghold at Akrotiri. From archaeological evidence, we know that the Mycenaeans invaded Crete after the disaster, and that their civilization, like that of the conquered Minoans, disappeared, leaving only fragmented artifactual evidence of its existence. But we know nothing about the relationship between the civilization of Prepalatial Crete and Mycenae.

Arthur Evans believed that the Minoans not only had conquered the islands of the Aegean but also had invaded the mainland and conquered Mycenae and Tiryns. There is archaeological evidence to support his belief, including obviously Minoan objects found in the shaft graves, such as the gold rings that show goddesses, warriors, or huntsmen, and the silver bull’s-head rhyton with a gold rosette on the animal’s forehead which closely resembles the steatite rhyton from Knossos. How did the craftsmanship of Crete get to the Peloponnese? We may never know, but “Cretan gold- and bronze-work could have been acquired either by peaceful trading contacts or by looting Minoan settlements,” wrote Leonard Cottrell in 1962, “by inducing Cretan craftsmen to work on the mainland or by carrying them off as slaves and obliging them to do so.”

A. J. B. Wace, a British archaeologist who worked for many years at Mycenae, took a completely opposing view. He believed that Mycenae had always been politically independent, although he admitted that the earlier Minoan civilization had obviously influenced the Mycenaean. He believed that Mycenaean crafts had a distinctive look, and even suggested that by the middle of the second millennium Mycenae had become more powerful and more commercially successful than Evans’s Knossos. Finally, Wace suggested that the Mycenaeans had even conquered Knossos, and had ruled from the throne room from 1450 to 1400 B.C. (The “Mycenaean” derivation of the griffin frescoes in the throne room at Knossos strongly supports this view.) While he was working on his massive, four-volume Palace of Minos (1921–36), Evans wrote The Shaft Graves and Beehive Tombs of Mycenae and Their Interrelation, in which he claimed that Wace had got his Minoan chronology all wrong. (Although Wace was probably closer to the truth than Evans, his confrontations with the godfather of Minoan archaeology redounded to his detriment. While Evans was alive [he died at the age of ninety in 1941], Wace was not allowed to dig at any site in Greece.)

Palace design is another indication that the two civilizations had developed separately: where the Minoan palace was designed around a large, open central courtyard, the Mycenaean palaces were centered on the megaron, a square interior room that contained the king’s throne, and, in the middle of the room, a large circular hearth surrounded by four massive columns. We even have what amounts to an eyewitness description of the megaron at Pylos. In the Odyssey, when Nausicaä directs Odysseus to her father Nestor’s palace, she says, “Directly you have passed through the courtyard and into the buildings, walk quickly through the great hall [megaron] until you reach my mother, who generally sits in the firelight by the hearth, weaving yarn stained with sea-purple, and forming a delightful picture, with her chair against a pillar and her maids sitting behind. My father’s throne is close to hers, and there he sits, drinking his wine like a god.”

There are no eyewitness descriptions of Minoan throne rooms—there are no eyewitness descriptions of Minoan anything—but we have the excavated palaces themselves, which appear to demonstrate that the precedents for architectural designs came from very different sources. As excavated by the University of Cincinnati archaeologist Carl Blegen (and perhaps described in detail by Homer), the palace at Pylos gives us an idea about the way Mycenaean royalty lived. (No other palace has been reconstructed as extravagantly as Knossos, but meticulous renderings of the palace at Pylos were drawn by Dutch illustrator Piet de Jong, under Blegen’s direction.) The palaces were as elaborate and richly ornamented as those in Crete, with painted walls, ceilings, and floors. Where the Minoan palaces were unfortified, the Mycenaeans surrounded theirs with massive circuit walls, built of roughly dressed boulders, with the interstices filled with smaller stones and rubble. The famous Lion Gate is the main entrance to the walled citadel of Mycenae.

HOWEVER MISGUIDED his motives and erroneous his conclusions, Heinrich Schliemann uncovered the richness of the Mycenaean culture, which had been buried in the earth for almost three thousand years. In addition to the gold treasures that he found at Mycenae, he also revealed evidence of a civilization as sophisticated as the Minoan that it replaced, with great palaces with frescoes and pillared walls, bridges, fortresses, sculpture, paintings of astonishing complexity, pottery, weaving, and records kept in Linear B. The far-ranging Mycenaeans traded pottery and olive oil for copper and tin, from which they forged their bronze weapons.

We look in awe at the accomplishments of the Mycenaeans, but to this day, we do not know what caused the precipitate collapse of their civilization. Did pirates from across the seas invade and conquer? Was it internal strife in the form of revolution? Climatic change, such as a prolonged drought? Did the peasants, starved for food, storm the citadels? Was the collapse of their culture an inspiration for the Atlantis story?

In his 1966 Discontinuity in Greek Civilization, Rhys Carpenter opines that the downfall of the Mycenaeans was caused not by human intervention but rather by climatic change. He quotes Herodotus, who wrote that after the Trojan War, Crete was so beset by famine and pestilence that it became virtually uninhabitable. He asks, “Could Herodotus by any chance have had access to a true tradition?” Yes indeed: “This, then, is my interpretation of the archaeological evidence coupled with ancient oral tradition: a ‘time of trouble’ was occasioned by climatic causes that brought persistent drought with its attendant famine to most of mainland Greece; and it was this unlivable condition of their native abode that forced the Mycenaeans to emigrate, ending their century-long prosperity.”

The Mycenaeans had penetrated the greater part of the Greek mainland by about 1400 B.C., but some sort of serious troubles befell them by about 1250, when some of the major centers were destroyed by fire. By the end of the thirteenth century B.C., Pylos had burned to the ground. Unlike the Egyptians, who documented and dated virtually all of their activities, the Minoans and the Mycenaeans did not appear to engage in such validation, or if they did, we have not encountered it. We know that successive invasions by the Libyans, the Assyrians, and, in 332, Alexander of Macedonia, resulted in the expiration of dynastic Egypt, a civilization that had prospered for almost three millennia, but all we know about the end of the Minoan civilization is that it occurred suddenly. Many of the early archaeologists, like Schliemann and Evans, were the victims of their own egos—they would brook no disagreement whatsoever with their conclusions—but they were also subject to the limitations of contemporaneous archaeological science. The shrines, grave sites, frescoes, sealstones, and funerary offerings are silent on the questions that perplex historians. Indeed, few of the objects in question were intact when found, and many of them—particularly the frescoes—had crumbled and fallen to the floor. To reconstruct the frescoes, or, for that matter, to identify the wall from which they fell, is often exceedingly difficult. Many of them have been imaginatively redrawn, based on the most fragmented evidence, and it is therefore possible that even artifactual evidence can be a subject for controversy, not only about what it means but about what it is. (The “saffron gatherer” turned out to have been a monkey pulling flowers from a pot.)

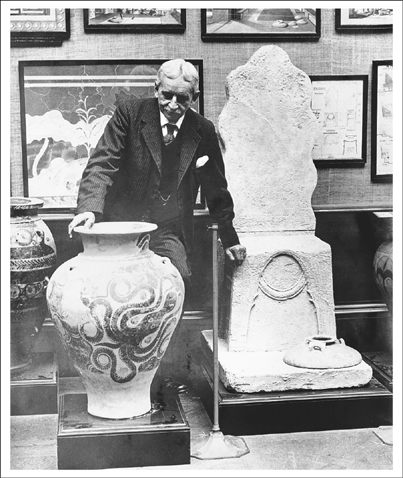

AT THE ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM in Oxford, Sir Arthur Evans rests one hand on a jar decorated with an octopus motif, and the other on a cast of the throne at Knossos. (illustration credit 5.13)

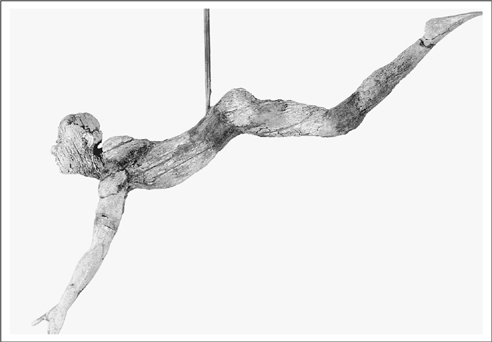

SPYRIDON MARINATOS (1901–1974), the first archaeologist to propose that the Minoan civilization had been destroyed by the volcano on Santorini (illustration credit 5.14)

As early as 1939, Spyridon Marinatos had suggested that the settlements in Crete (Amnisos, Mallia, Gournia, and Hagia Triada—but not Knossos) were destroyed by tsunamis, earthquakes, and aerial vibrations originating with the eruption of Thera around 1450 B.C. World War II and civil unrest in Crete prevented Marinatos from pursuing his theories, but he returned to Santorini in 1958 to investigate the results of the 1956 earthquake that had damaged two thousand houses and killed fifty-three people. In 1956, Professor Marinatos was named director of antiquities and monuments of Greece. He had excavated Minoan buildings at Amnisos and Vathypetro in Crete, and had explored late Bronze Age settlements in Messenia on the mainland. “This island,” he wrote of Crete in 1972, “can fire the imagination of any archaeologist. For 1,500 years, beginning about 3000 B.C., Crete and the Cyclades dominated the Mediterranean. Here, indeed, was the birthplace of European civilization.” In 1932, as an ephor (keeper of antiquities) in Crete, he had unearthed fragments of a fresco at Amnisos, but, he wrote, “what really piqued my interest … were the curious positions of several huge stone blocks that had been torn from their foundations and strewn toward the sea.… I found a building near the shore with its basement full of pumice. This fact I tentatively ascribed to a huge eruption of Thera, which geologists then thought had occurred around 2000 B.C.” When he became visiting professor at the State University at Utrecht in 1937, he took the opportunity to examine the voluminous Dutch material on the explosion of Krakatau in what was then the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), and concluded that it blew with “a mere fraction of the destructive force unleashed 3,400 years before by the eruption of Thera.” In 1939, Marinatos published “The Volcanic Destruction of Minoan Crete” in the journal Antiquity, but even then there were doubters. As Marinatos him-self observed (in his 1972 National Geographic article), “The editors added a note pointing out ‘that in their opinion the main thesis of this article requires additional support from excavation at selected sites.’ ” Additional excavations have revealed a civilization of astonishing achievement and complexity, which, because of its uniqueness and mysterious origins, has led any number of people to equate Knossos with the myth of Atlantis. But the continued presence—albeit largely underground—of Knossos has presented almost insurmountable problems for those who have tried to see Knossos as a city that sank into the sea.

THE ARCHAEOLOGIZING OF ancient civilizations is a process not unlike trying to assemble a gigantic jigsaw puzzle with many pieces lost or broken, and in some cases—like that of Knossos—where the complete image of the puzzle, usually printed on the box, is missing. Some of these materials enable us to obtain a fleeting glimpse into ancient life, but more often than not, we cannot accurately interpret what we see. For example, one of the most important single artifacts in all of Minoan archaeology came not from a palace but from the “royal villa” at Hagia Triada (also spelled Aghia Triadha), to the west of Phaistos, excavated by the Italian archaeologist Federico Halbherr in 1910. Located on the protected southern coast of Crete, Hagia Triada was only a short distance from Phaistos, raising the possibility that the villa was occupied by a noble family doing business at the palace. (The ancient name of this location is not known, so it takes its name from the fourteenth-century [A.D.] church near the villa: Hagia Triada means “Holy Trinity” in Greek.)

In a thick-walled tomb just north of the villa, Halbherr found a painted sarcophagus, completely intact, that had been carved from a single block of limestone. Based on the style of the paintings, he dated it from approximately 1450 B.C., before the final destruction of the palace at Knossos. The painted decorations, on a coating of plaster, were almost as clear and bright as the day they were painted. This coffer is only fifty-two inches long, not long enough for a full-length adult, so the body was probably interred with its legs tucked up, like the bodies placed in the predynastic Egyptian graves, and those of the late Stone and Bronze ages in Western Europe.

LIBATION AND OFFERING scene from the Hagia Triada sarcophagus, showing two double-ax columns at the extreme left, with three figures approaching them, two with libation jars (one actually pouring something into a receptacle between the two columns), and, following behind her, another woman carrying a yoke with two more libations. Bringing up the rear is a figure playing a sort of lyre. Facing in the opposite direction are two men, each carrying a small calf, and a third, cradling a funerary boat. At the very right margin, a single armless figure stands, perhaps the mummy or the spirit of the deceased. (illustration credit 5.15)

The sarcophagus is painted on all four sides, and even the sturdy legs are decorated with a typical Minoan swirl motif. Each end bears a painting of two goddesses in a chariot, one drawn by goats, the other by griffins. On one long side, a trussed bull lies on a table; below the table two goats crouch, presumably awaiting their turn. Directly below the bull’s neck, which appears to be pierced by a dagger, is a ceremonial vase to catch the blood seen flowing over the lip of the table. With her back arched regally, a statuesque priestess stands at the bull’s tail; a piper stands partially hidden behind the bull; and at the head, another priestess sets her hands upon an altar, identifiable by the libation jug and the basket of fruit above it. Beyond the altar is a tall column, wider at the top than at the bottom, surmounted by an elaborate double ax with a bird (or bird spirit) perched on the top (a motif repeated on the other side), and an altar topped by four pairs of the “horns of consecration,” a popular image in Minoan religious symbolism. (There were two—or three—additional figures painted on the left side of this face of the sarcophagus, but the plaster has chipped off, leaving only their feet and the lower parts of their skirts.)

The other side of the Hagia Triada chest contains two double-ax columns at the extreme left, with three figures approaching them, two with libation jars (one actually pouring something into a receptacle between the two columns) and, following behind her, another woman carrying a yoke with two more libations. Bringing up the rear is a figure playing a sort of lyre, whose gender is not evident, because the gown and upper torso are similar to those of the yoke carrier, but the hair is shorter, with a curl in front like the other, obviously male figures, and the skin is rendered in the dark reddish hue that differentiates men from women in comparable Minoan imagery. (The face and hands of the piper on the other side are also reddish.) On the right half of this side, facing in the opposite direction from the two women and the musician, are two men, each carrying a small calf,* and a third, cradling a funerary boat. At the far right margin of this tableau, a single armless figure stands, perhaps the mummy or the spirit of the deceased, before an altar like those on the obverse, but missing the horns of consecration. It is possible that the sacrifices and libations, along with the musical accompaniment, were ceremonies accompanying the interment of an important personage, but any interpretation is only educated guesswork. As Higgins (1974) wrote of this extraordinary artifact, “These scenes raise many problems, but are evidently concerned with the worship of the dead.”

In addition to the discovery of Hagia Triada, Halbherr was responsible for the first excavations of the palace at Phaistos, second in size and splendor only to Knossos. The first palace was built around 1900 B.C., was destroyed by a great earthquake around 1700, and was rebuilt on a more majestic scale than the first one. The palace consists of the usual Minoan complex of rooms, courtyards, storerooms, light wells, and staircases, and a pair of adjoining rooms that have been named the “Queen’s Megaron” and the “King’s Megaron,” with floors of alabaster tiles and frescoed walls. (From the dimensions of the rebuilt palace at Phaistos, it has been possible to calculate that the standard unit of measurement for Cretan architects was 30.36 centimeters, only a fraction of an inch shorter than the standard English foot.) It was here that the famous “Phaistos Disk” was discovered, a clay disk with spirals of hieroglyphics on both sides. Stamped into the three-quarters of an inch-thick clay were human forms, parts of the body, tools, weapons, animals, plants, and even ships. Since the designs were recurring (there are 241 impressions of 41 different types), it was obvious that the same stamps had been used repeatedly. In 1984, a professional cryptographer named Steven Roger Fischer claimed to have broken the code that had baffled archaeologists and linguists since the disk was discovered in 1910. In his 1997 book Glyphbreaker, Fischer wrote that the language of the disk is recognized as an ancient Minoan language that is similar to Mycenaean Greek, and contains a call to arms to repel the invading Carians from Anatolia.

Although Knossos seems to have been the capital and the exemplar for most of Cretan architecture, the excavation of several other palaces, such as Zakros, Phaistos, and Mallia, indicate that the Minoans inhabited the entire island. Investigations of sites like these, which have been affected by volcanic eruptions, are usually difficult to locate. (The exception is Akrotiri in Santorini, where potsherds were found on the surface, and where the soil occasionally collapsed under the weight of a passing donkey, indicating hollows beneath.) When buildings collapse and are then covered with ash, there is often very little evidence above the ground. Even such well-documented sites as Pompeii went unexcavated for seventeen centuries. Until Fouqué dug in the ashes of Santorini in 1860, no one even suspected that there was anything there, and even though Troy was the most famous city in Greek mythology, Heinrich Schliemann did not uncover it until 1876. Until Arthur Evans began to dig at Knossos, a city that had been buried and lost for more than thirty-five hundred years, no one knew that a great city lay smothered in the ashes of the hill of Kephala.

THE “PHAISTOS DISK” is terra-cotta, approximately six inches high and three-quarters of an inch thick. It contains examples of 3,600-year-old Minoan hieroglyphics that were first translated in 1984 by Steven Roger Fischer, a professional cryptographer. (illustration credit 5.16)

Around the turn of the twentieth century, British archaeologist David Hogarth (1862–1927) discovered a dozen buildings at Zakros, on the coast at the eastern end of Crete. He found clay and stone utensils buried under the ash, and enough artifactual material to suggest that there had been a substantial settlement there. But the British School at Athens, which was sponsoring the part of Evans’s excavations that he did not fund himself, decided to concentrate on the spectacular palace at Knossos. Until fairly recently, the only access to Zakros was by foot or muleback over the mountains, or by boat, and sixty years would pass before another archaeologist examined the ruins at the end of the road.

In 1962, Nicholas Platon (whose last name is “Plato” in French) began a methodical excavation at Zakros. “The results,” he wrote, “fully justified my expectations. Four large Minoan mansions were found and excavated, as well as two peak sanctuaries [shrines erected on a high point of land] and cemeteries and burial caves of the Minoan and early Greek periods.” In 1963, however, results surpassed his expectations, for he uncovered another palace, not as large as Knossos but replete with splendid artifacts, including a bull’s-head rhyton like the one found in the queen’s throne room at Knossos, and another rhyton that was elaborately inscribed with decorations that show a peak sanctuary. The “sanctuary rhyton” shows a building with columned openings crowned with ceremonial horns—exactly the same shape as the massive, abstract horns at Knossos. Cavorting around the building on the sanctuary rhyton are wild goats with gracefully curving horns, identifying them as the subspecies of goat (Capra aegagrus cretensis) that lives only in Crete. (As Platon described it in his 1971 book, Zakros, the Cretan wild goat is “almost extinct”; it has probably now disappeared forever.) There appears to have been an emphasis on goats at Zakros, since Platon writes, “It is natural … that the goddess in her aspect of Mistress of Animals should have at Zakros wild goats as her attendants. Other evidence of her role as Goddess of Wild Goats is provided by ritual vessels with spouts and handles in the form of a wild goat’s head with long, curved horns.”