UNTIL HEINRICH SCHLIEMANN’S excavations on the Greek mainland in 1876, hardly anything was known about the Aegean Bronze Age. In fact, it was generally assumed that Greek culture commenced somewhere around 776 B.C., the year of the first Olympiad. Prior to that date, Greek prehistory consisted of the epic poems of Homer: the Iliad and the Odyssey, the heroic tales of the confrontation between Achilles and Hector, and the Trojan War. The storied culture of the ancient Greeks was thought to consist of romantic fables with no basis in historical fact.

Because Schliemann was committed to finding the legendary city of Troy, he believed he had found it when he uncovered royal shaft graves at Mycenae, and that the artifacts in the tombs had belonged to the heroes of the Trojan War. Also in the 1860s, during excavations in the volcanic debris on the island of Thera, Bronze Age settlements were unearthed that corresponded with the Mycenaean shaft graves. Although some evidence of prehistoric settlements was uncovered, Santorini would remain undisturbed by inquisitive archaeologists until 1967, when Spyridon Marinatos began to dig at Akrotiri.

In 1965, Marinatos made his first reconnaissance of the island of Santorini. He reasoned that the little village of Akrotiri, located on the southern hook of the island, offered a safe harbor from northwesterly storms and might have been the site of an early settlement. His instincts were rewarded when he was told about certain places where the soil had subsided in such a way as to indicate that it might be layered atop ruined buildings. He also found donkeys drinking out of stone troughs that he recognized as massive prehistoric mortars. He decided to dig in the shallow ravine that ran from Akrotiri to the sea, and within hours, he realized that he had found the remains of a prehistoric city.

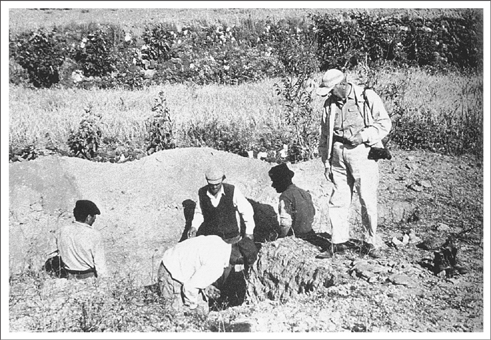

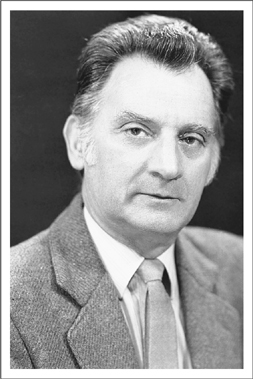

PROFESSOR SPYRIDON MARINATOS (right) supervising the dig at Akrotiri (illustration credit 7.1)

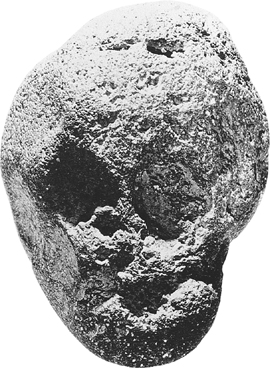

In 1968, during the second season of excavations at Thera, Marinatos found fragments of a wall painting that contained the head of a man, several birds in flight, and the head of a monkey. Then they found another monkey fresco, this one showing a band of blue monkeys scrambling over a rocky landscape. Indeed, Akrotiri’s most significant contribution to the opening of the long-closed book on Aegean prehistory is its graphic arts, particularly the wall paintings. The colors available to the artists of Akrotiri were red, black, yellow, blue, and cream, with the lighter colors often serving as background. They painted on small areas, such as the space between two windows, and on full expanses of blank walls. Although the paintings were begun on wet plaster, the artists evidently did not try to maintain the wet condition, and often completed the paintings when the plaster was completely dry. For this reason, the term “fresco” (from the Italian for “fresh”) is not strictly accurate. Paintings on dry plaster tend to flake, while those painted when the plaster was wet are much better preserved. They painted wild animals, such as antelopes and monkeys, semidomesticated animals like cats and goats, various mythological creatures, and the subjects that give us our best view of life in prehistoric Greece: people.

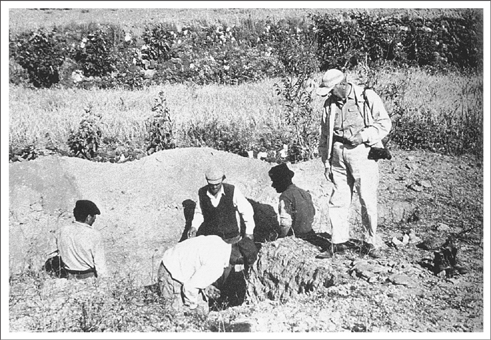

Most of the frescoes discovered at Akrotiri were fragments, sometimes found in the dust, sometimes barely clinging to the crumbling walls. For those that had fallen, the pieces had to be painstakingly reassembled, and often, large portions of a mural were lost and had to be reconstructed. As Marinatos and his crew (which included his daughter Nanno, the British scholar Colin Renfrew, and Christos Doumas, the second-in-command, who would go on to become the project’s director) slowly removed the piled-up volcanic ash, they saw what Renfrew described as “one of the most perfect works of art to have been preserved for us from prehistoric times.” It was a wall painting, completely intact, of a rocky landscape with lilies growing on the rocks, and swallows swooping overhead.* This spectacular painting is now known as the “Spring Fresco” or the “Fresco of the Lilies.” The lilies and the swallows are realistic, but the contours of the red and gray rocks—obviously of volcanic origin—are highly exaggerated, prompting Nanno Marinatos to write that she was “not at all convinced by the suggestion that they depict a typical preeruption Thera setting. Rather they represent the idea of rocky ground using the conventions of Minoan art.”

In his first excavations, Marinatos found rooms that contained cups and lamps, but reasoned (correctly) that he had discovered the upper story of a multistory building, and took pains to protect it from the elements. He covered the site with corrugated sheet metal, which protected the fragile buildings from the rain, and fiberglass to let in the sunlight as they continued their work. Ten complete buildings were uncovered, which Marinatos identified with a complex system of names, including alpha, beta, gamma, and delta for the first four, then Xesté (the Greek term for the dressed stone blocks known as ashlars), with Arabic numerals employed to identify particular buildings (e.g., Xesté 3), and, finally, names that referred to particular features or locations, such as the House of the Ladies, where, on facing walls (the east and the west), are two incomplete murals showing mature women, identifiable by their long hair and full breasts. In the next alcove to the north are frescoes showing tall papyrus plants. (This and the “Spring Fresco” are the only rooms that show solely plants.) Papyrus did not grow in Thera, and probably not even in Crete. When he found what was obviously a street that ran north-south between several buildings—one of which yielded some artisans’ tools—Marinatos named it Telchines Street, after a primitive tribe that was sometimes represented in mythology as the inventors of the useful arts. As of 1992, an area of about 10,000 square meters (32,800 square feet) of Akrotiri had been excavated, and it is estimated that this may be half or less than the total.

THE “FRESCO OF THE LILIES,” or “Spring Fresco,” in building Delta 3 at Akrotiri, with swallows flying over the flowers. This design was copied for the “treasure room” in the 1975 film The Man Who Would Be King, which has nothing whatever to do with the Aegean. (illustration credit 7.2)

Spyridon Marinatos died of a stroke on October 1, 1974, while supervising the installation of a new device for removing ash from the dig at his beloved Akrotiri. According to his daughter, he had been working “intensively and without interruption” since 1967. He concluded his 1972 National Geographic article with these words: “Eventually [visitors] will be able to stroll through the streets and glance through the doors and windows of a once-flourishing Minoan city, a city that died by violence, a city that in the pathos of its ruin—its pulse of life stopped virtually in mid-beat—stands as an epitaph for the brilliant, seagirt world of Minos.” Pursuant to his instructions, Marinatos was buried in room 16 of the Delta Building. Christos Doumas, Marinatos’s deputy, assumed command of the project, and in addition to his prodigious output of papers and articles, and his chairmanship of numerous symposia dedicated to Theran studies, he is the author of The Wall Paintings of Thera, the definitive study of these monuments in the history of art. Nanno Marinatos, educated in the United States (she has a Ph.D. from the University of Colorado at Boulder), maintained the family tradition of passionate interest in Thera. She became an authority on the interpretation of Theran frescoes and, in 1985, published Art and Religion in Thera: Reconstructing a Bronze Age Society.

The building known as “Building Beta” (“B1”) was so badly damaged by a later flood that it has not been possible to locate the entrance. Nevertheless, excavators have uncovered enough pottery vessels to infer that this was a private residence, its upper stories decorated with intriguing wall paintings, including a realistically drawn pair of antelopes. Spyridon Marinatos had originally identified them as oryxes (Oryx beisa), but his daughter says “they are a hybrid of the Thomson and Grant’s Gazelle and also Oryx beisa.* It is thus probable that the iconographical form is derived from other pictures and that the painter had never seen the real animals.… The animals are rendered with surprising liveliness in simple, outline form.” Because antelopes are not known in the Aegean islands, this iconography is probably borrowed from Egypt, but as Vanschoonwinkel notes in his 1990 study of animal representations in Theran and other Aegean arts, “The steps in the transmission of this motif are missing at this time.”

THE ANTELOPES and “boxing boys” from Beta 1 at Akrotiri. Like everything else about the wall paintings of Thera, the reason for the juxtaposition of these disparate images is unknown. (illustration credit 7.3)

The “Blue Monkey Fresco” in Beta 6 again shows an animal not native to the island as the subject of a major painting. But unlike the single, supplicant monkey in Xesté 3, the simians in Beta 6 cavort in great numbers all over one wall. These monkeys are identifiable as to type and, therefore, as to origin. They are guenons, long-tailed ground dwellers from Africa, and even though color is not a good determinant (the Minoan wall painters had a very limited palette), the monkeys in the paintings closely resemble the species coincidentally known as “blue monkeys,” Cercopithecus mitis. Found from central to south Africa, blue monkeys are characterized by their solid, slate-gray to bluish coloration, with a distinct white band across the forehead, clearly visible in the Akrotiri paintings.

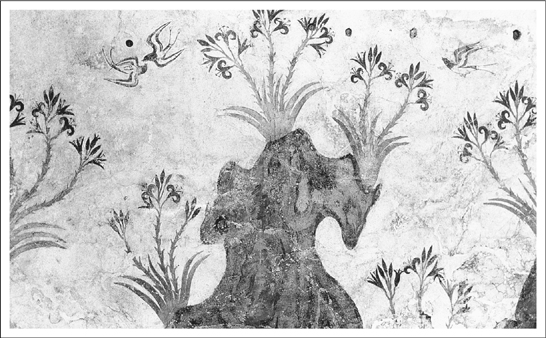

Aris Poulianos (1972) describes a petrified skull, referable to the genus Cercopithecus, that was found in the ruins of Thera, which suggests to him that the monkeys were drawn from real animals, perhaps kept as pets as they were in Egypt.† The skull was found “among the sea pebbles and rocks on the east side of Thera on the Monolithos coast in the summer of 1966” by Edward Loring, who is described by Poulianos as “a foreign scientist looking for evidence of the lost continent … [who] actually spent many summers actually combing the island for evidence.” Whatever Loring was looking for, he seems to have found the only “evidence” of a living creature that perished in the eruption of Thera around 1500 B.C. In his discussion (“The Discovery of the First Known Victim of Thera’s Bronze Age Eruption”), Poulianos wrote, “Perhaps his masters were less fortunate than he and were burned off behind, and this monkey was assigned by fate to give us sole testimony of this biblical destruction.” In later years, Loring’s “monkey skull” was dismissed as spurious; if not an outright fake, it was certainly not what Loring (or Poulianos) said it was. Also, as Dorothy Vitaliano points out, “neither Mavor, nor Galanopoulos and Bacon offer any explanation of what would constitute an unprecedented case of fossilization—replacement by lava—in terms that would satisfy any paleontologist.” The monkeys of the frescoes, however, are included in this discussion because, as we shall see, their presence in ancient Greece might have contributed to the Plague of Athens, a catastrophe that may have been peripherally included in Plato’s discussion of the downfall of Atlantis.

THE SO-CALLED monkey’s-head fossil, found at Santorini in 1966. Used to demonstrate that there were monkeys killed in the volcanic eruption, the “fossil” is actually a lava bomb. (illustration credit 7.4)

In addition to those of Beta 6, monkeys appear in three other Theran wall paintings: in Xesté 3, a young woman sits on a platform flanked by a griffin and a monkey; in Room 2 of the West House, there is a fragmentary frieze showing monkeys holding swords or playing a lyre; and Sector A shows part of a monkey with its forepaws raised in front of an altar.

No palace has been found at Akrotiri—nor is one expected—but in addition to the ordinary houses, there are “mansions,” which include ceremonial rooms and smaller rooms that appear to have been service areas used for the storage and preparation of food. Xesté 3, for example, can be divided into two distinct sections, identified as eastern and western. The small rooms of the western section contained storage jars and pottery and were therefore probably used for food preparation; the eastern section has two large rooms and two stairways, and when the doors between the rooms were opened, a large space was formed, which Nanno Marinatos believed was “suitable for public gatherings.” This building also contains a small, square room similar to those that Arthur Evans had found at Knossos, and that he had decided were “lustral basins,” employed in ritual purification ceremonies. Others saw them as baths, but since there are no drains attached to these rooms, they have now been interpreted as holy areas known as adyta (singular: adyton), into which priests would descend to make offerings. The second story may have been used for sleeping quarters, but most of the upper level collapsed into the lower, and is less easy to read. This building also contains the “Goddess Fresco,” and, with the adyton, indicates that Xesté 3 was a building with a primarily religious function—as Nanno Marinatos describes it, “suitable for cult activities of a mystical character.” It is obvious that the wall paintings in Xesté 3 were more than mere decorations; they depicted specific events or symbolic iconography that had substantial importance to the inhabitants of Akrotiri.

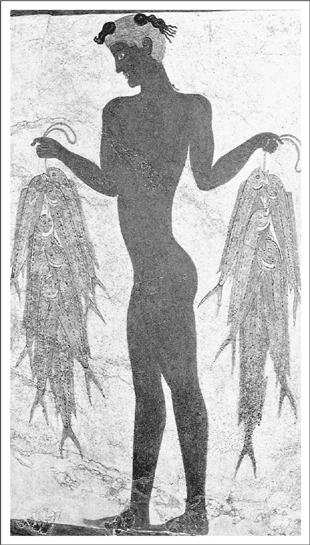

The “fishermen” paintings, one of which is much better preserved than the other, show two naked youths with their heads shaven (indicated by the bluish color), with only topknots of hair remaining. The fisherman on the west wall holds one bunch of three mackerel; on the north wall, the boy holds seven dolphinfish (also known as dorado or mahimahi) in his right hand, and five more in his left. Both these species of fishes are fast swimmers and would not be—even today, with sophisticated spearguns—catchable by divers. Why, then, are these two naked boys shown with strings of these particular fish? Nanno Marinatos writes that “their blue heads, which denote partial shaving, and their nudity” indicate that they are “performing a special function as youthful adorants,” and suggests that they are making an offering to their deity.

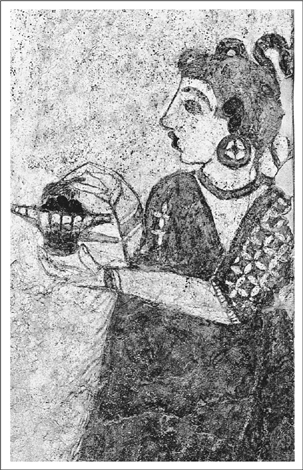

The “priestess” (on the southeast doorjamb of Room 4 where it connects to Room 5) is dressed in a floor-length chiton of a terra-cotta color, with blue and white trim. She wears heavy gold earrings, a necklace, bracelets, and a snakelike device in her blue hair. (Nanno Marinatos sees her coiffure somewhat differently: “If the blue color of her hair denotes partial shaving, then the lock on top of the head is dressed in such a way as to resemble a snake.”) Her lips and left ear (she is shown in left profile) are painted red, and in her hands she holds a glowing brazier. “Perhaps,” wrote Nanno Marinatos, “she passed from room to room censing it or perfuming the air of the house. This is why she is depicted on a door jamb.”

THE YOUNG “fisherman” painted on the wall of West House carries seven dolphinfish (dorado or mahimahi) in his right hand, and five more in his left. Did he catch them, or is there another explanation? (illustration credit 7.5)

According to Christina Televantou’s 1990 reconstruction, the “Miniature Frieze” ran around all four walls of Room 5, even though there are no fragments to indicate that there was a painting on the west wall. The piece entitled “Frieze with the Fleet” shows ships heading from one end of the wall to the other, crossing open water from one settlement to another, powered by ranks of oarsmen. It has been suggested (Doumas 1992) that “the painter of the Miniature Frieze sought to tell the story of a major overseas voyage, in the course of which the fleet visited several harbours and cities, five in all, which the artist has successfully depicted on the four walls of Room 5.” An alternative interpretation, proposed by Nanno Marinatos, is that the friezes show a religious festival, exemplified by the festive ornamentation of the ships; the existence of a woman of high rank seated near the symbolic horns of consecration; the fact that the ships are being paddled, rather than rowed, which suggests a ceremonial function; and the presence of a group of youths leading an animal to a religious sacrifice. Further, she sees the festival as celebrating war or aggression, shown by the boat crews’ shields and spears, the grappling iron, and the floating bodies, which suggest a battle, not a shipwreck.

As shown in the frescoes, the island settlements contain buildings in the Minoan style; multistoried structures of different heights, built of trimmed blocks. Town II is seen as a coastal community, with pastoral activities depicted in the upper portions of the painting, including herdsmen with sheep, goats, and cattle; a troop of helmeted warriors with shields and spears; and, below them, the wrecks of ships with drowned victims floating in the water. On the east wall is a frieze that shows a river, and thus interrupts the “voyage” of the ships. We see the river from above, and among the palm trees and bushes are various animals, including a wildcat and a jackal in pursuit of ducks. This scene also contains a drawing of a griffin, with the wings and head of an eagle and the body of a lion. The river continues into the next segment of the frieze, and may in fact be a continuation. The landscape at the left, from which the ships are departing, shows not only a town (Town IV) but the mountainous landscape in which the town is set, complete with rocks, trees, streams, and heavy-antlered deer being pursued by a lion. It is not evident that the painter of the frieze intended it to portray a particular location, but, writes Nanno Marinatos, “even if the artist wanted to draw imaginary places, he would incorporate elements with which he was familiar.” Thus we see a depiction of the naval and terrestrial architecture of Thera, from approximately 1600 B.C. In this scene, which is believed to show some sort of ritual “nautical festival,” the largest ship, dubbed “the Admiral’s,” is festooned with crocus pendants strung over the covered pavilion, in which the passengers are seated comfortably. Dolphins frolic around the vessels, and the “the Admiral’s” ship is decorated with paintings of lions and dolphins. Each of the large vessels has a figurehead at the stern, usually in the form of a lion, and a long, graceful bowsprit. A single mast is stepped amidships, and while most of the ships are being rowed by oarsmen, one of the smaller ships has a single square sail raised, and the details of the rigging are clearly shown. They are headed for Town V, a series of stacked buildings with people looking out over the sea at the arriving flotilla from the flat rooftops, and from open windows. Doumas (1992) writes that “the topographic features of the landscape, the configuration of the harbour and the beached boats, the multi-storied buildings with Aegean architectural traits, and the appearance of the inhabitants argue for the identification of Town V as Akrotiri.”

ALTHOUGH WE DO NOT know the true identity of the woman depicted in this Akrotiri wall painting, she is commonly referred to as the “priestess.” (illustration credit 7.6)

In her 1990 discussion of the friezes (“New Light on the West House Wall-Paintings”), Christina Televantou summarized her interpretations:

We are of the opinion that the pictorial programme of the West House was organized so as to project a highly complex central idea, the age-old relationship between man, in this case the Theran, and the sea.… Firstly through the projection of the activities of the Aegean fleet in the Eastern Mediterranean, which we believe is the setting in which some of the events depicted on the Miniature Frieze are enacted, though with special emphasis on the participation of the Theran fleet. Secondly by projecting martial alertness of this fleet, and, by extension, the economic and political role of the Therans in the Aegean and perhaps the Aegean peoples in the Eastern Mediterranean.… Finally, the significant role of sea-faring activities in the upbringing of Theran youth is also projected.*

Except for domesticated animals, beasts of burden, birds of the air, and fishes and dolphins of the sea, the Greek islands are largely devoid of exotic wildlife. There are no native monkeys, antelopes, deer, or lions.† There are certainly no griffins. However they got there, lions appear prominently in the wall paintings of Akrotiri, in landscapes, as the painted decorations and figureheads on ships, and even on libation cups—but there are hardly any lions on the Minoan artifacts from Crete.

THE “ADMIRAL’S SHIP” in the long frieze in the West House at Akrotiri, showing a high-ranking official being transported. Other than that, we know nothing about this sophisticated painting. (illustration credit 7.7)

According to Fouqué (1869), “The men of Santorini were laborers or fishermen; they cultivated cereals, made flour, extracted oil from olives, raised flocks of goats and sheep, fished with nets; they produced decorated vases and were acquainted with gold and probably copper.” It is clear that Minoan Akrotiri had been a town of some consequence. For its time, it was also immense, covering some thirty-one acres. There were two- and three-story buildings, separated by narrow, winding streets; houses with substantial doors and stone staircases, with large windows to let in the sunlight for which the Cyclades are still renowned. Some of the bigger buildings, such as the West House and the House of the Ladies, were freestanding, while many of the others seem to have had common walls and were bunched together. These “apartment blocks,” such as the Beta, Gamma, and Delta buildings, comprise many rooms, some of which have been identified as dwellings, but not as many kitchens as might have been expected have been found, suggesting that more than one family may have used the cooking facilities. The buildings identified as the “North Magazine” appear to have been used for storage and food preparation (many storage jars and a hearth have been found there), and the presence of large windows facing the street at ground level has prompted the suggestion that they might have served for the distribution of goods to the townspeople. A lion’s-head rhyton found in the magazine may indicate that cult activities were also carried out there. In the upper level of the mill building, a rhyton in the form of a cropped-horn bull covered by a net was found, of which Nanno Marinatos wrote, “It seems that this bull is a representation of a sacrificial animal because the net and the cutting of the horns suggest a ritual preparation. It is very probable that the sacrificial ritual was connected with the harvest of grain or with its grinding into flour in Crete.”

The houses were built of local materials, including small stones, held together with a mortar of mud and straw. As at Knossos, the walls were strengthened with wooden beams, which were often exposed indoors and out. Trimmed ashlar blocks were used to face the larger buildings, many of which included multiple rooms to serve different functions. There were bathrooms with terra-cotta tubs, and on the second floor, to take advantage of the gravity flow, stone toilets (that may once have had wooden seats), connected by a series of clay pipes to a drainage system that ran beneath the streets. Theran potters appear to have turned out great quantities of ceramic vessels, including cookware, incense burners, ewers, jugs, drinking cups, and storage jars, all ornamented with brilliantly colored images of flowers, ears of barley, birds, fishes, dolphins, and abstract designs.

A LARGE ROOF has been constructed over the entire dig at Akrotiri to ensure that the excavated ruins are not affected by the weather. (illustration credit 7.8)

There is little question that the settlement at Akrotiri was Minoan. Sinclair Hood (1990) has analyzed the architecture and found that it “suggests a basically similar way of life at Akrotiri and in major Cretan centers.” J.-C. Poursat’s observations on the commercial interactions between Crete and Thera (also published in the 1990 Thera and the Aegean World III) address the importance of Thera as a port and indicate that it might have been the most significant international harbor of its time. Indeed, the dominance of the Cretans (what M. H. Wiener calls the “Minoan Thalassocracy”) influenced the Cyclades, the Dodecanese, and even the coasts of Asia Minor.

Frescoes in Thera have a white background, while those of Knossos are polychromed, but the subject matter and style are largely similar.

During the 1890s, von Gaertringen excavated the ancient city of Thera. (The island is also known as Thera, and the capital city, overlooking the caldera, is Phira, sometimes spelled Fíra.) “Ancient Thera” (as the guidebooks call it) is a settlement high on the hill called Mesa Vuono, originally settled by the Greeks of the ninth century B.C., some six hundred years after the devastating volcano eruption. Because it sits on a ridge 1,000 feet above sea level, the town commands the most dramatic position on the island, probably chosen for reasons of defense. Following the configuration of the ridge, ancient Thera runs on a northeast-southwest axis, and is a long, narrow settlement, with the Gymnasium of the Ephebes at one end, the Gymnasium of the Guard at the other, and various Hellenic buildings, such as the Temple of Dionysus, the Temple of Apollo Karneios, and various public and private buildings in between.

In Akrotiri, pottery pieces and many complete examples are the dominant artifactual evidence of the settlement. More than fifty different shapes have been distinguished, many of them locally produced and others imported, probably from Crete. They range in size from the pithoi, which are large storage jars, often taller than a man, to vases and drinking cups. Their shape and decoration define and date them, and their provenance helps to date the settlement itself. The pottery of Akrotiri was decorated with a variety of themes, including abstract designs and representations of the plant and animal kingdoms. Small oblong vessels, known as kymbai and resembling miniature bathtubs, and decorated with dolphins, swallows, or chamois, have been found only at Akrotiri.

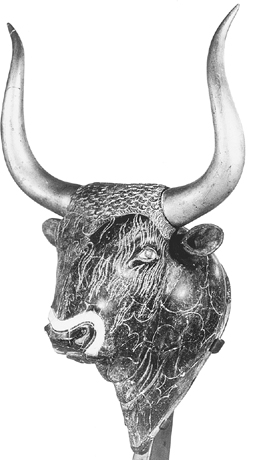

Rhytons are libation cups, usually in exotic shapes, but sometimes they are just elongated cones. At Akrotiri, there have been found rhytons in the shape of a polled bull, a boar’s head, the head of a lioness, and, probably most dramatic of all, given the importance of the bull in Minoan culture, the bull’s head. A spectacular rhyton, made of black steatite in the shape of a bull’s head, was found in the palace complex at Knossos, and another of the same shape was found in the “Hall of Ceremonies” at Zakros. Each one was badly shattered, but they were reconstructed to show a hole at the nape of the neck, and another at the tip of the muzzle, respectively for filling the vessel and for pouring the libations. The Knossos rhyton, half of which was intact, had eyes made of rock crystal, jasper, and clamshell. The shape of the horns, missing in both cases, has been reconstructed on the basis of a silver rhyton, found at Mycenae—undoubtedly imported from Crete—in which the gracefully curved horns were made of gilded wood. Two more rhytons, both made of faience in the shape of a hornless bull (or perhaps a cow), were found at Zakros. (Also at Zakros, a foot-high, cone-shaped rhyton was found that was decorated with raised images of goats and numerous representations of the altars crowned with ceremonial horns.)

THE BULL’S-HEAD RHYTON from the Little Palace at Knossos. Found without the horns, the eight-inch-high head is made of black steatite, and the eyes are rock crystal. (illustration credit 7.9)

In Ninkovich and Heezen’s synopsis, “The greater part of the settlement … together with the central part of the island, fell into the magma chamber during the big eruption.” It has been too easy to attribute the fall of Knossos to a destructive volcano, but a careful examination of the archaeological and geological evidence does not support this simplistic resolution of one of the great mysteries of prehistory. Knossos was in decline—indeed, it may have been conquered and burned—before the volcano erupted in 1450 B.C. (Marinatos discovered that objects found beneath the lower tephra in Santorini cannot be dated later than 1520 B.C., suggesting that the big eruption occurred after the Minoan settlement had been destroyed.) The central settlement at Knossos, which Arthur Evans believed was ruled by King Minos, was rebuilt and struggled on for years before collapsing altogether. R. W. Hutchinson (1962) accepted Marinatos’s theory of the volcanic destruction of LM-I palaces, but believed that the decline of Minoan Crete was the result of an invasion by the Mycenaeans (Achaeans). The palaces at Knossos survived the pillaging Mycenaeans, but the eruption of Thera closed the book on one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in the history of civilization. Only through the concerted efforts of archaeologists, historians, and geologists are we beginning to get an idea of the glory that was Crete.*

The discovery of Minoan pottery, frescoed walls, and storerooms with amphorae still in place paled beside the discovery that under the fallen stone walls there was no trace of the pumice that covered everything else. Based on that evidence, Marinatos concluded that “a strong earthquake had destroyed the building; thereafter a shower of tephra from an exploding volcano buried it.” Marinatos decided that the eruption of Thera had ended Minoan culture.

Revelations about the Minoan civilization, combined with information about the eruption of the volcano, have produced any number of studies, culminating in the establishment in 1989 of the Thera Foundation, dedicated to the study and dissemination of information on every aspect of the history of Thera. The foundation has sponsored (so far) four symposia and issued no fewer than six massive volumes of learned papers on every aspect of Theran studies. In his concluding remarks to the Third Congress, Dr. Vassos Karageorghis coined a new category for the archaeological lexicon: “Therology.” While Pliny gave his name to a type of eruption, and Stromboli and Pelée have types of volcanic eruptions named for them, Thera is the only volcano immortalized by a whole field of study. One effect of this concentrated study is that it supersedes previous work, mostly by utilizing that previous work as a substructure for the more recent studies. Thus, the eruption, the archaeology, and the history of Santorini (as well as the influences of mainland Greece, Crete, and other Aegean islands) are probably best interpreted through the most recent publications—most often, those of the Thera Foundation. In the capital city of Thera, the foundation has reconfigured an earthquake-damaged building into a thoroughly modern conference center, which was the site of the 1996 symposium on the wall paintings of Thera. And just in time, since at the site, Professor Doumas and his dedicated corps of students and volunteers are uncovering and reassembling even more fascinating examples of this site-specific art form.

CHRISTOS DOUMAS, archaeologist in charge of the recent excavations of the Minoan settlement of Akrotiri, on the island of Santorini (illustration credit 7.10)

Santorini is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Aegean, for all the wrong reasons. It is probably the most spectacular of the Cyclades—in fact, it is one of the most spectacular islands in the world. (In the 1994 guidebook The Cyclades, it is referred to as “most people’s favourite Greek island … with the awesome mixture of towering, sinister, multi-coloured volcanic cliffs, dappled with the ‘chic’-est, most brilliant-white, trendiest bars and restaurants in the country.…”) It looks not unlike an atoll: a hollowed-out circle, with high, striated cliffs surrounding a deep blue crater. In the middle of this volcanic caldera—for that is what Santorini is—two black lava islands rise, a silent testimony to its unbelievably violent history.

The tourists arrive by plane, by ferry, and by cruise ship. Usually less than a day is allocated to the exploration of Santorini, with a pronounced emphasis on shopping. Shops sell everything from ice cream and doughnuts to museum replicas of Greek antiquities and expensive gold jewelry. In the summer, the main city of Thera (also called Phira) attracts nomadic students in hordes. During the day, they cruise the narrow roads of Santorini on buzzing mopeds, motorbikes, and motorcycles, going to the beaches, and in the evening—and all through the night—they hang out, drinks in hand, making contact with their fellow travelers from every possible location in Europe and America.

But behind the “happy-tourist-in-the-Greek-Islands” façade there lurks a story of a stupendous volcanic eruption that blew up most of an island; an entire civilization that abruptly vanished from the face of the earth; and—not surprisingly—intimations of the Lost City of Atlantis.

The archaeological dig at Akrotiri belongs on the itinerary of visitors to Santorini. Because of the fragile nature of the dig, only forty people at a time are allowed to walk through, on specified paths and under the watchful eye of a guide. As the tourists gawk, archaeological students and volunteers under the direction of Christos Doumas are carefully removing fragmented evidence of the Minoan occupation of the site, some thirty-five hundred years ago.

Spyridon Marinatos’s dream of a “walk-through” Minoan civilization will not be realized in our lifetime. (The closest we will come to such a concept is Evans’s “reconstructions” at Knossos.) Excavations of this sort go painfully slowly, as each wall, stairway, and fragment of wall painting has to be gently uncovered, often with a tiny brush, and then photographed, mapped, and carefully removed. As it is cleared away, the ash is placed in leather buckets, and then transported by wheelbarrow to a dump site outside the dig. (Archaeology may have made some technological advances, but the method of removing unwanted ash or dirt is the same now as it was in Schliemann’s time, the difference being that researchers today are much more careful than Schliemann was.) In the case of pottery or frescoes, that is only the beginning, since the restorers then have to try to reassemble the pieces, often without a clue as to the appearance of the final artifact. Professor Doumas has dozens of assistants, volunteer and otherwise, meticulously reassembling wall paintings and pottery. They are nowhere near up to speed, however, since there are batteries of filing cabinets and boxes containing thousands of fragments that will not see the light of day for many years. Even if he had the money—which he does not—to pay more restorers, the sheer weight of the archaeological evidence would occupy hundreds of people for decades.

With its sophisticated art and architecture and its wealth of archaeological mysteries, not to mention the mysterious disappearance of its people, it is tempting to align the Minoan civilization with Atlantis. Indeed, many people have done just that. Just as Atlantis represents one of the greatest mysteries of ancient literature, so then do the palaces at Knossos and Phaistos, and the settlement at Akrotiri, exemplify one of the greatest puzzles in all of archaeology.

* In the 1975 John Huston film The Man Who Would Be King, based on the story by Rudyard Kipling and starring Michael Caine, Sean Connery, and Christopher Plummer, two soldiers, mustered out of the British army in India, decide to cross the Himalayas to “Rajistan,” where they intend to proclaim themselves kings and loot the country’s fabled riches. In the film, the “treasury” contains the sumptuous booty of Alexander the Great, evidently stored there since he invaded northern India some two thousand years earlier. The walls of the Himalayan palace are decorated with exact replicas of the paintings of the lilies and swallows of the “Spring Fresco” in room Delta 2 at Akrotiri.

* Gazelles are small, delicate creatures, and the only aspect of the Akrotiri paintings that is at all gazellelike is the curving horns. Oryxes, on the other hand, are heavyset antelopes (classified with the group commonly known as “horse antelopes”) with straight or slightly curved horns. Everything about the Akrotiri antelopes calls to mind an oryx—including the striking body and face pattern—but the horns say “gazelle,” which suggests that Nanno may be correct in her “hybrid” theory; not that the antelopes were actually hybrids, but that the artist combined the characteristics of animals he had never seen.

† In his 1969 Atlantis: The Truth Behind the Legend, Galanopoulos identifies a “fossilized monkey’s head found on Santorin in 1966” as “a gibbon, probably of the species Colobinae, mostly found in Ethiopia.” Gibbons are not monkeys (they are apes); they are not found anywhere near Ethiopia (they are Asiatic); and they are not members of the subfamily Colobinae, which actually includes such diverse monkeys as the guerezas of Africa, the sacred langurs of India, and the proboscis monkeys of Borneo.

* It is worth noting here that Plato described the harbors in the metropolis of Atlantis as consisting of “two rings of land, and three of sea, like cartwheels, with the island at their center and equivalent from each other, making the place inaccessible to man (for there were still no ships or sailing in those days).”

† The closest lions at that time were probably in North Africa, six hundred miles across the Mediterranean. Of course, Egypt was also in North Africa, and lions were probably hunted by royalty, although they do not appear in Old Kingdom reliefs. The famous Lion Gate at Mycenae, made around 1250 B.C., shows two lions heraldically positioned around an architectural column with their forefeet resting on an altar in the Cretan style. Around 650 B.C., long after the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations had fallen, the great cats would appear in the spectacular Assyrian reliefs of Assurbanipal’s lion hunts, which were unearthed in 1849 by Austen Henry Layard at Kuyunjik, on the banks of the Tigris in what is now Iraq. Of these remarkable works, art historian Kenneth Clark wrote, “On these Assyrian reliefs, executed over a period of more than two hundred years, the depiction of lion-hunts produced a series of masterpieces unsurpassed in the ancient world.”

* In Four Thousand Years Ago: A World Panorama of Life in the Second Millennium B.C., Geoffrey Bibby re-creates the daily life of Minoan nobles at Knossos, including the bull games (where an occasional amateur “sprang into the ring in the pauses between the teams, to make a pass or two at one of the bulls and to retire to polite applause after a single somersault”), trade with Egypt, and, finally, the invasion of the Achaeans, who burned the palace and enslaved the Minoans. Those who escaped, he says, settled in Lebanon, Egypt, and Cyprus.