CONCEPT 30

Rinsing (Not Soaking) Makes Rice Fluffy

Cooking rice is easy, but cooking rice well isn’t. Many competent cooks claim they can’t cook rice at all. It scorches. It’s mushy. The rice is sticky when they want it fluffy. Convenience products, like converted or instant rice, are supposed to take some of the guesswork out of the process, but their texture and flavor make them poor options. Once you understand how rice works, though, you will realize that cooking it well is not hard.

HOW THE SCIENCE WORKS

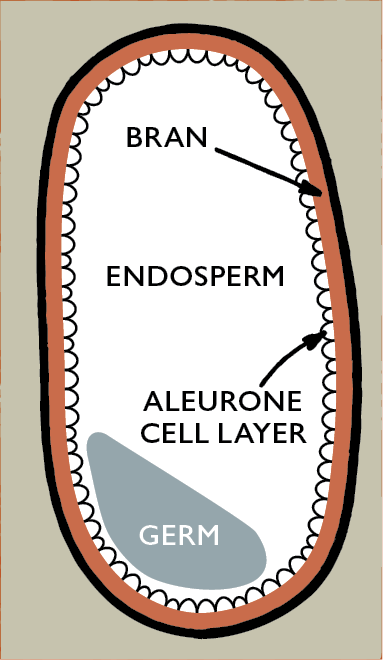

Rice is a seed from the plant known as Oryza sativa. When harvested, rice is covered by a protective husk. After the husk is removed, we’re left with brown rice, which is composed of three parts: the bran (which encloses a layer of cells called the aleurone layer, which is rich in oil and enzymes), the germ, and the endosperm. For several thousand years, whole-grain rice has been parboiled and then milled in order to remove the bran and germ, leaving only the starchy endosperm. Parboiled, polished rice (known simply as white rice) is the most common form called for in recipes.

Like potatoes or pasta, the main challenge when cooking rice is figuring out how to control the starches. However, while potatoes or pasta are often cooked in lots of water to wash away excess starch, rice requires a more precise cooking method. If you boil and drain rice, you end up washing away its delicate flavor and the grains turn soggy and bloated. Rice is best cooked with a measured amount of liquid in a covered pot. The cover ensures that the liquid doesn’t evaporate but instead eventually gets absorbed by the rice. (If too much water evaporates, the rice will burn before it becomes tender.)

Starch granules, which are the primary component of rice, tend not to absorb water when held at room temperature. As you heat rice in water, however, the energy from the rapidly moving water molecules begins to loosen the bonds between the starch molecules, allowing the water to seep in. This in turn causes the starch granules to swell and release some gummy starch molecules that then act like a glue to hold the grains together. The rice softens and becomes sticky, or “starchy.”

Like potatoes (see concept 26), rice contains two kinds of starch molecules: amylose and amylopectin. The amount of amylose and the protein content of the starch granules determine the textural properties of the rice—from separate and fluffy to sticky and gummy—when it is cooked. Though there are exceptions, rice with higher amylose and protein content (like long-grain rice) cooks into grains that are separate, light, and fluffy. Rice with a lower amylose and protein content (like Arborio) cooks into grains that are moist and tender, with a greater tendency to cling together.

As a result of the differences in the amylose and protein content, the starch granules in long-grain rice swell and gelatinize at a much higher temperature (158 degrees) than the granules in medium-grain rice (144 degrees). Starch granules that gelatinize at a lower temperature release more amylose, even though they have a lower amylose content. The higher amount of released amylose causes the grains to cling together.

Long-grain rice contains about 22 percent amylose and 8.5 percent protein, and the grains are four to five times longer than they are wide. Long-grain rice needs the most water for cooking and, when cooked, remains as separate grains that harden as they cool (because of the higher amylose content). We prefer long-grain rice for dishes like pilaf.

Medium-grain rice contains about 18 percent amylose and 6.5 percent protein, and the grains are two to three times longer than they are wide. This rice needs a bit less water to cook than long-grain rice and cooks up tender and somewhat clingy. Medium-grain rices like Arborio are perfect for dishes like risotto, as they can be creamy but not sticky.

Short-grain contains about 15 percent amylose and 6 percent protein and the grains are almost round. This rice needs the least amount of water and can be quite sticky and tender when cooked. Short-grain rice is ideal for dishes like sushi, in which the grains need to stick together.

To determine the value of soaking rice in water before cooking, which is a technique purported to help rice cook faster and better, we devised a simple test: Some recipes call for soaking brown rice for three hours, so that’s just what we did. We soaked one batch of Brown Rice, then cooked it according to our recipe, but with a slightly reduced amount of water. We made another batch of rice that had not been soaked (but was rinsed before cooking) using the same recipe with the correct amount of liquid. We repeated the test using long-grain white rice and basmati rice.

THE RESULTS

Every single variety of rice that had been soaked was overcooked and bloated, with grains that tended to blow out.

THE TAKEAWAY

To be frank, soaking was a waste of time. Even with brown rice, which, with its bran, germ, and aleurone layers intact, can take two to three times longer to cook than white rice, the results were overly tender and unpleasant. Soaking caused the rice to absorb too much water, which in turn caused the starch granules to swell as soon as the heat was applied.

Does that mean that there’s no place for water in the world of rice preparation? Not necessarily. We find that the extra step of rinsing long-grain white or basmati rice in several changes of water is indispensable for a pilaf with distinct, separate grains. Rinsing washes away starches on the surface of these grains that helps them cook up lighter and fluffier. What about rinsing brown rice? Our tests showed no benefit (or harm). Because the bran is still intact, brown rice doesn’t have starch on its exterior. So rinsing doesn’t accomplish anything—except for wasting time and water.

COVERED STOVETOP COOKING AT WORK

RICE PILAF

When making rice pilaf, we add just enough water so that when it is fully absorbed the rice is tender and perfectly cooked. A covered pot is essential here. Without a tight lid, the water will evaporate from the pot before being absorbed by the rice, and the rice will burn before it is fully cooked.

SIMPLE RICE PILAF

SERVES 6

You will need a saucepan with a tight-fitting lid for this recipe. You can substitute basmati rice for the long-grain white rice.

|

2 |

cups long-grain white rice |

|

3 |

tablespoons unsalted butter or vegetable oil |

|

1 |

small onion, chopped fine |

|

3 |

cups water |

|

1 |

teaspoon salt |

|

|

Pepper |

1. Place rice in colander or fine-mesh strainer and rinse under cold running water until water runs clear. Place strainer over bowl and set aside.

2. Melt butter in large saucepan over medium heat. Add onion and cook until softened but not browned, about 4 minutes. Add rice and cook, stirring constantly, until grains become chalky and opaque, 1 to 3 minutes. Add water, salt, and pepper to taste, increase heat to high, and bring to boil, swirling pot to blend ingredients. Reduce heat to low, cover, and simmer until all liquid is absorbed, 18 to 20 minutes. Off heat, remove lid and place kitchen towel folded in half over saucepan; replace lid. Let stand for 10 to 15 minutes. Fluff rice with fork and serve.

RICE PILAF WITH CURRANTS AND PINE NUTS

Add 2 minced garlic cloves, ½ teaspoon ground turmeric, and ¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon to softened onion and cook until fragrant, about 30 seconds. When rice is off heat, before covering saucepan with towel, sprinkle ¼ cup currants over top of rice (do not mix in). When fluffing rice with fork, toss in ¼ cup toasted pine nuts.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Rice pilaf should be fragrant and fluffy, perfectly steamed, and tender. While recipes for rice pilaf abound, none seem to agree on the best method for guaranteeing these results; many espouse rinsing the rice and soaking it overnight, but we wondered if this was really necessary for a simple rice dish. For the best pilaf, we start with long-grain white rice (though basmati rice is even better if you have it on hand). We find that an overnight soak isn’t necessary (see Test Kitchen Experiment), but rinsing the rice before cooking gives us beautifully separated grains. Sautéing the rice in butter for just a minute gives our pilaf great flavor.

THE RIGHT RICE Pilaf should be light and fluffy so you want to use long-grain rice. Long-grain white rice is neutral in flavor, providing a backdrop for other foods. Nonetheless, higher-quality white rice offers a pleasingly chewy al dente texture and a slightly buttery natural flavor of its own. The buttery notes are caused by a naturally occurring flavor compound, 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline, and higher levels lend an almost popcornlike taste. Basmati rice, which can be used instead of long-grain white rice, is prized for its nutty flavor and sweet aroma. Indian basmati, unlike American-grown basmati, is aged for a minimum of a year, though often much longer, before being packaged. Aging dehydrates the rice, which translates into grains that, once cooked, expand greatly, and more so than any other long-grain rice. American-grown basmati is not aged and hence doesn’t expand as much as Indian-grown rice. When shopping, make sure that the label indicates that the basmati rice has been aged. The only “bad” choice of rice for this recipe is converted rice, which is steam-treated before packaging. This gelatinizes the starch in the center of the grain and removes some of the starch from the rice exterior, making the rice less likely to become starchy or sticky when cooked. The result is “bouncy” rice, with an assertive flavor our tasters don’t like.

USE LESS WATER The conventional ratio of 2 parts water to 1 part rice makes rice too sticky and soft. We find the right ratio to be 3 parts water to 2 parts rice, which also takes into account the effects of rinsing the rice before cooking.

SAUTÉ THE RICE Sautéing the rice in butter develops the nutty notes in the rice and helps the individual grains to maintain their integrity. Also this step gives us the chance to sauté an onion (or another flavorful ingredient) first.

BRING TO A BOIL, REDUCE HEAT Once the rice looks translucent around the edges, add the water and salt, bring to a boil, reduce the heat to the lowest setting, and cover the pot. The rice should be tender (and with all the water absorbed) after 18 to 20 minutes.

STEAM OFF THE HEAT After boiling, the rice will be a bit heavy. To lighten it up, we slide a towel under the lid and let the pot sit off the heat for 10 to 15 minutes. The towel absorbs some of the moisture in the pot and helps produce rice that is nice and fluffy. Just fluff with a fork (to separate the grains) and serve.

COVERED OVEN COOKING AT WORK

BROWN RICE AND MEXICAN RICE

For slow-cooking rice dishes, even a tight cover might not solve all the problems. You need to even out the cooking of the rice so the bottom won’t scorch. Moving the operation to the oven does this.

BROWN RICE

SERVES 4 TO 6

To minimize any loss of water through evaporation, cover the saucepan and use the water as soon as it reaches a boil. An 8-inch ceramic baking dish with a lid may be used instead of the baking dish and aluminum foil. To double the recipe, use a 13 by 9-inch baking dish; the baking time does not need to be increased.

|

1½ |

cups long-grain, medium-grain, or short-grain brown rice |

|

21⁄3 |

cups water |

|

2 |

teaspoons unsalted butter or vegetable oil |

|

½ |

teaspoon salt |

1. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 375 degrees. Spread rice in 8-inch square baking dish.

2. Bring water and butter to boil, covered, in medium saucepan. Once boiling, immediately stir in salt and pour water over rice in baking dish. Cover baking dish tightly with 2 layers of aluminum foil. Transfer baking dish to oven and bake rice until tender, about 1 hour.

3. Remove baking dish from oven and uncover. Fluff rice with fork, then cover dish with kitchen towel and let rice stand for 5 minutes. Uncover and let rice stand for 5 minutes longer. Serve immediately.

CURRIED BAKED BROWN RICE WITH TOMATOES AND PEAS

Increase butter to 2 tablespoons and melt in 10-inch nonstick skillet over medium heat. Add 1 minced small onion and cook until translucent, about 3 minutes. Add 1 minced garlic clove, 1 tablespoon grated fresh ginger, 1½ teaspoons curry powder, and ¼ teaspoon salt and cook until fragrant, about 1 minute. Add one 14.5-ounce can drained diced tomatoes and cook until heated through, about 2 minutes. Set aside. Substitute vegetable broth for water and reduce amount of salt to 1⁄8 teaspoon. After pouring broth over rice, stir tomato mixture into rice and spread rice and tomato mixture into even layer. Bake as directed, increasing baking time to 70 minutes. Before covering baking dish with kitchen towel, stir in ½ cup thawed frozen peas.

BAKED BROWN RICE WITH PARMESAN, LEMON, AND HERBS

Increase butter to 2 tablespoons and melt in 10-inch nonstick skillet over medium heat. Add 1 minced small onion and cook until translucent, about 3 minutes; set aside. Substitute low-sodium chicken broth for water and reduce salt to 1⁄8 teaspoon. Stir onion mixture into rice after adding broth. Cover and bake rice as directed. After removing foil, stir in ½ cup grated Parmesan, ¼ cup minced fresh parsley, ¼ cup chopped fresh basil, 1 teaspoon grated lemon zest, ½ teaspoon lemon juice, and 1⁄8 teaspoon pepper. Cover dish with kitchen towel and proceed as directed.

BAKED BROWN RICE WITH SAUTÉED MUSHROOMS AND LEEKS

Substitute low-sodium chicken broth for water and reduce amount of salt to 1⁄8 teaspoon; bake as directed. When rice has about 10 minutes baking time remaining, melt 1 tablespoon unsalted butter with 1 tablespoon olive oil in 12-inch nonstick skillet over medium-high heat. Add 1 leek, white part only, sliced into ¼-inch-thick rings, and cook, stirring occasionally, until wilted, about 2 minutes. Add 6 ounces cremini mushrooms, trimmed and sliced ¼ inch thick, and ¼ teaspoon salt and cook, stirring occasionally, until moisture has evaporated and mushrooms are browned, about 8 minutes. Stir in 1½ teaspoons minced fresh thyme and 1⁄8 teaspoon pepper. After removing kitchen towel, stir in mushroom-leek mixture and 1½ teaspoons sherry vinegar; serve immediately.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Brown rice should have a nutty, gutsy flavor and more textural personality—slightly sticky and just a bit more chewy—than white rice. To achieve this ideal, we stayed close to the water-to-rice ratio established in our Simple Rice Pilaf, settling on 21⁄3 cups water to 1½ cups rice. But unlike our white rice method, here we cooked the rice in the oven to approximate the controlled, indirect heat of a rice cooker. A couple of teaspoons of butter or oil added to the cooking water added mild flavor while allowing the earthy, nutty flavor of the rice to take center stage.

MOVE IT TO THE OVEN Brown rice doesn’t require more water (just an extra tablespoon compared to white rice) but it does need a lot more time to soften. Brown rice is a whole-grain rice with the hull intact (white rice has had this hull removed). This hull is the reason it takes just about twice as long to cook brown rice as white rice. Moving the cooking to the oven allows the rice to be cooked more gently and evenly, reducing the risk of the bottom layer of rice burning, which frequently happens if brown rice is cooked on the stovetop.

USE LESS WATER Most recipes for brown rice cooked on the stovetop prevent scorching by upping the amount of water (usually to a 2:1 ratio). But this can result in very soggy, overcooked rice. We find that using less water (and then trapping the moisture in a covered baking dish) yields a much better product. Boiling water before adding it to the rice (instead of using cold tap water) keeps the oven time to one hour. A tight seal on the baking dish is paramount—this is why we use the two layers of foil.

ADD A LITTLE FAT AND SALT Make sure to season the rice before it goes into the oven. A little bit of added fat gives mild flavor while keeping the rice fluffy.

FLUFF AND LET REST After the rice comes out of the oven, fluff the rice in order to separate the grains, and then cover the dish with a clean towel to absorb some moisture.

MEXICAN RICE

SERVES 6 TO 8

Because the spiciness of jalapeños varies from chile to chile, we try to control the heat by removing the ribs and seeds (the source of most of the heat) from those chiles that are cooked in the rice. It is important to use an ovensafe pot about 12 inches in diameter so that the rice cooks evenly and in the time indicated. The pot’s depth is less important than its diameter; we’ve successfully used both a straight-sided sauté pan and a Dutch oven. Whichever type of pot you use, it should have a tight-fitting, ovensafe lid. Vegetable broth can be substituted for the chicken broth.

|

2 |

tomatoes, cored and quartered |

|

1 |

white onion, peeled and quartered |

|

3 |

jalapeño chiles, 2 stemmed, seeded, and minced, 1 stemmed and minced |

|

2 |

cups long-grain white rice |

|

1⁄3 |

cup vegetable oil |

|

4 |

garlic cloves, minced |

|

2 |

cups low-sodium chicken broth |

|

1 |

tablespoon tomato paste |

|

1½ |

teaspoons salt |

|

½ |

cup minced fresh cilantro |

|

|

Lime wedges |

1. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 350 degrees. Process tomatoes and onion in food processor until smooth, about 15 seconds, scraping down bowl if necessary. Transfer mixture to liquid measuring cup; you should have 2 cups (if necessary, spoon off excess so that volume equals 2 cups).

2. Place rice in large fine-mesh strainer and rinse under cold running water until water runs clear, about 1½ minutes. Shake rice vigorously in strainer to remove excess water.

3. Heat oil in ovensafe 12-inch straight-sided sauté pan or Dutch oven over medium-high heat for 1 to 2 minutes. Drop 3 or 4 grains rice in oil; if grains sizzle, oil is ready. Add rice and cook, stirring frequently, until rice is light golden and translucent, 6 to 8 minutes. Reduce heat to medium, add garlic and seeded minced jalapeños, and cook, stirring constantly, until fragrant, about 1½ minutes. Stir in pureed tomatoes and onion, chicken broth, tomato paste, and salt, increase heat to medium-high, and bring to boil. Cover pan and transfer to oven; bake until liquid is absorbed and rice is tender, 30 to 35 minutes, stirring well halfway through cooking.

4. Stir in cilantro and reserved minced jalapeño with seeds to taste. Serve immediately, passing lime wedges separately.

MEXICAN RICE WITH CHARRED TOMATOES, CHILES, AND ONION

SERVES 6 TO 8

For this variation, the vegetables are charred in a cast-iron skillet, which gives the finished dish a deeper color and a slightly toasty, smoky flavor. A cast-iron skillet works best for toasting the vegetables; a traditional or even a nonstick skillet will be left with burnt spots that are difficult to remove, even with vigorous scrubbing. Vegetable broth can be substituted for the chicken broth. Include the ribs and seeds when mincing the third jalapeño.

|

2 |

tomatoes, cored |

|

1 |

white onion, peeled and quartered |

|

6 |

garlic cloves, unpeeled |

|

3 |

jalapeño chiles, 2 stemmed, halved, and seeded, 1 stemmed and minced |

|

2 |

cups long-grain white rice |

|

1⁄3 |

cup vegetable oil |

|

2 |

cups low-sodium chicken broth |

|

1 |

tablespoon tomato paste |

|

1½ |

teaspoons salt |

|

½ |

cup minced fresh cilantro |

|

|

Lime wedges |

1. Heat 12-inch cast-iron skillet over medium-high heat for about 2 minutes. Add tomatoes, onion, garlic, and halved jalapeños and toast, using tongs to turn them frequently, until vegetables are softened and almost completely blackened, about 10 minutes for tomatoes and 15 to 20 minutes for other vegetables. When cool enough to handle, trim root ends from onion and halve each piece. Remove skins from garlic and mince. Mince jalapeños.

2. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 350 degrees. Process toasted tomatoes and onion in food processor until smooth, about 15 seconds, scraping down bowl if necessary. Transfer mixture to liquid measuring cup; you should have 2 cups (if necessary, spoon off any excess so that volume equals 2 cups).

3. Place rice in large fine-mesh strainer and rinse under cold running water until water runs clear, about 1½ minutes. Shake rice vigorously in strainer to remove excess water.

4. Heat oil in ovensafe 12-inch straight-sided sauté pan or Dutch oven over medium-high heat, 1 to 2 minutes. Drop 3 or 4 grains rice in oil; if grains sizzle, oil is ready. Add rice and cook, stirring frequently, until rice is light golden and translucent, 6 to 8 minutes. Reduce heat to medium, add toasted minced garlic and toasted minced jalapeños, and cook, stirring constantly, until fragrant, about 1½ minutes. Stir in pureed tomatoes and onion, chicken broth, tomato paste, and salt, increase heat to medium-high, and bring to boil. Cover pan and transfer to oven; bake until liquid is absorbed and rice is tender, 30 to 35 minutes, stirring well halfway through cooking.

5. Stir in cilantro and reserved minced jalapeño with seeds to taste. Serve immediately, passing lime wedges separately.

Rice cooked the Mexican way is a flavorful pilaf-style dish, but we’ve had our share of soupy or greasy versions. With a whole host of ingredients in the pot it can be hard to get the rice to cook through evenly on the stovetop. Not to mention that excess stirring causes the rice to be extra starchy. We move the pot to the oven to solve both of these problems.

RINSE AND FRY Rinsing the rice washes away excess starch that can make this dish gummy. Frying the rice in 1⁄3 cup of oil imparts a rich, toasted flavor. Note that some recipes deep-fry the rice, but we found that this was unnecessary. Likewise, simply sautéing the rice in a tablespoon of oil didn’t impart the necessary richness.

USE TWO TYPES OF TOMATOES Most recipes use fresh tomatoes and we found out why—the versions with canned tomatoes tasted overcooked and too tomatoey. We did like the richer color of the versions made with canned tomatoes; we got this by adding a tablespoon of tomato paste. To further guarantee the right flavor, color, and texture, we stir the rice midway through cooking to reincorporate the tomato mixture.

ADD FLAVOR, TEXTURE We found pureeing the tomatoes into a pulp was best—and that we could puree the onion with the tomatoes as well. We prefer to mince garlic and chiles and sauté them in the pot with the rice, before adding the tomatoes and onion, to develop their flavor. We also cook in chicken broth for richer flavor.

FINISH FRESH While many traditional recipes consider fresh cilantro and minced jalapeño optional, in our book they are mandatory. The raw herbs and pungent chiles complement the richer tones of the cooked tomatoes, garlic, and onion. A squirt of fresh lime illuminates the flavor even further.

COVERED STOVETOP COOKING AT WORK

RISOTTO

Traditional risotto recipes call for constant stirring while the rice cooks. Stirring releases the starches in the rice, helping to create that iconic creamy sauce. We’ve revamped the traditional recipe to drastically reduce the stirring time, but still achieve the firm yet tender texture by not rinsing the rice, and flooding it with water.

NO-FUSS RISOTTO WITH PARMESAN AND HERBS

SERVES 6

This more hands-off method requires precise timing, so we strongly recommend using a timer.

|

5 |

cups low-sodium chicken broth |

|

1½ |

cups water |

|

4 |

tablespoons unsalted butter |

|

1 |

large onion, chopped fine |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

|

1 |

garlic clove, minced |

|

2 |

cups Arborio rice |

|

1 |

cup dry white wine |

|

2 |

ounces Parmesan cheese, grated (1 cup) |

|

2 |

tablespoons minced fresh parsley |

|

2 |

tablespoons minced fresh chives |

|

1 |

teaspoon lemon juice |

1. Bring broth and water to boil in large saucepan over high heat. Reduce heat to medium-low to maintain gentle simmer.

2. Melt 2 tablespoons butter in Dutch oven over medium heat. Add onion and ¾ teaspoon salt and cook, stirring frequently, until onion is softened, 5 to 7 minutes. Add garlic and stir until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Add rice and cook, stirring frequently, until grains are translucent around edges, about 3 minutes.

3. Add wine and cook, stirring constantly, until fully absorbed, 2 to 3 minutes. Stir 5 cups hot broth mixture into rice; reduce heat to medium-low, cover, and simmer until almost all liquid has been absorbed and rice is just al dente, 16 to 19 minutes, stirring twice during cooking.

4. Add ¾ cup hot broth mixture and stir gently and constantly until risotto becomes creamy, about 3 minutes. Stir in Parmesan. Remove pot from heat, cover, and let stand for 5 minutes. Stir in remaining 2 tablespoons butter, parsley, chives, and lemon juice. To loosen texture of risotto, add remaining broth mixture to taste. Season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately.

NO-FUSS RISOTTO WITH CHICKEN AND HERBS

SERVES 6

This more hands-off method requires precise timing, so we strongly recommend using a timer.

|

5 |

cups low-sodium chicken broth |

|

2 |

cups water |

|

1 |

tablespoon olive oil |

|

2 |

(12-ounce) bone-in split chicken breasts, trimmed and cut in half crosswise |

|

4 |

tablespoons unsalted butter |

|

1 |

large onion, chopped fine |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

|

1 |

garlic clove, minced |

|

2 |

cups Arborio rice |

|

1 |

cup dry white wine |

|

2 |

ounces Parmesan cheese, grated (1 cup) |

|

2 |

tablespoons minced fresh parsley |

|

2 |

tablespoons minced fresh chives |

|

1 |

teaspoon lemon juice |

1. Bring broth and water to boil in large saucepan over high heat. Reduce heat to medium-low to maintain gentle simmer.

2. Heat oil in Dutch oven over medium heat until just starting to smoke. Add chicken, skin side down, and cook without moving until golden brown, 4 to 6 minutes. Flip chicken and cook second side until lightly browned, about 2 minutes. Transfer chicken to saucepan of simmering broth and cook until chicken registers 160 degrees, 10 to 15 minutes. Transfer to large plate.

3. Melt 2 tablespoons butter in now-empty Dutch oven over medium heat. Add onion and ¾ teaspoon salt and cook, stirring frequently, until onion is softened, 5 to 7 minutes. Add garlic and stir until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Add rice and cook, stirring frequently, until grains are translucent around edges, about 3 minutes.

4. Add wine and cook, stirring constantly, until fully absorbed, 2 to 3 minutes. Stir 5 cups hot broth mixture into rice; reduce heat to medium-low, cover, and simmer until almost all liquid has been absorbed and rice is just al dente, 16 to 19 minutes, stirring twice during cooking.

5. Add ¾ cup hot broth mixture to risotto and stir gently and constantly until risotto becomes creamy, about 3 minutes. Stir in Parmesan. Remove pot from heat, cover, and let stand for 5 minutes.

6. Meanwhile, remove and discard skin and bones from chicken and shred meat into bite-size pieces. Gently stir shredded chicken, remaining 2 tablespoons butter, parsley, chives, and lemon juice into risotto. To loosen texture of risotto, add remaining broth mixture to taste. Season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Classic risotto can demand half an hour of stovetop tedium for the best creamy results. Our goal was five minutes of stirring, tops. Typical recipes dictate adding the broth in small increments after the wine has been absorbed (and stirring constantly after each addition), but we add most of the broth at once and cover the pan, allowing the rice to simmer until almost all the broth is absorbed (stirring just twice).

DON’T STIR We have rethought this recipe to reduce stirring to a bare minimum. Flooding the rice with most of the liquid at the outset and then using the lid to help the rice cook evenly is our unique trick here. (But be sure to measure the liquid with care; success is dependent on the correct ratios and volumes.) We don’t rinse the Arborio rice; we want that extra starch to help make our risotto creamy. (Traditionally, it’s the stirring that causes the rice to release its starch and create the creamy “sauce.”) Stirring also prevents sticking or scorching, but by flooding the rice and then bringing that liquid to a boil, we’re letting the natural jostling of the rice take the place of stirring—our rice doesn’t burn, and we get a great creamy sauce.

USE A DUTCH OVEN We swap out the saucepan for a Dutch oven, which has a thick, heavy bottom, deep sides, and tight-fitting lid—perfect for trapping and distributing heat as evenly as possible. Also, its wider surface area means there’s less differential in cooking rates between top and bottom; the rice is spread out in a thinner layer in the pot.

COOK WITH RESIDUAL HEAT We stir the rice twice in the first 16 to 19 minutes of cooking to help release some starch and build our sauce. After a second addition of broth, we stir the pot constantly until the risotto is creamy, which takes just three minutes. We then remove the pot from the heat, throw on the cover, and wait for five minutes. Without sitting over a direct flame, the heavy Dutch oven maintains enough residual heat to finish off the rice to a perfect al dente—thickened, velvety, and just barely chewy. Adding the Parmesan cheese before the off-heat “cooking” helps to build this creamy sauce.

FINISH WITH FLAVOR Just before serving, we stir in extra butter to make the sauce velvety and add herbs and a squeeze of lemon.