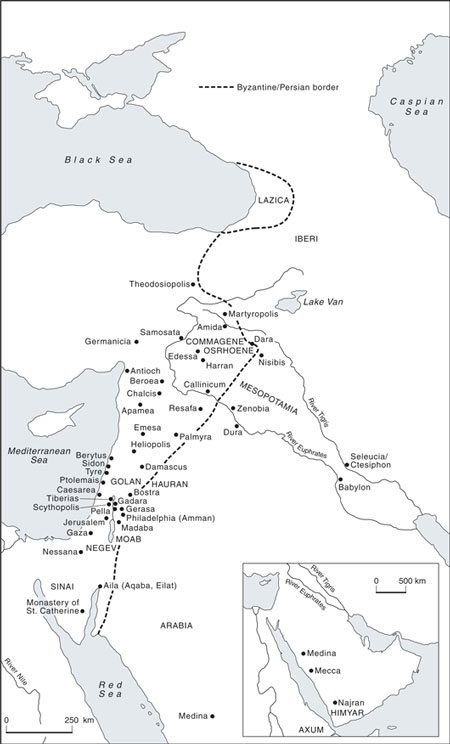

Map 8.1 The east in the sixth century

8

The Eastern Mediterranean – A Region in Ferment

The last chapter underlined the amount of recent scholarship devoted to the fate of towns, and the efforts of scholars to discover whether, and why, there may have been a ‘decline’ in the sixth century. Undoubtedly in the case of the east, much of the motivation for this lively interest derives from hindsight – from our awareness that the Arab conquests were just round the corner, and our knowledge that most of the eastern provinces were to be so quickly lost to the eastern empire. In a striking number of cases, the inhabitants of the cities we have been discussing simply surrendered them to the invaders. Now more than ever, given contemporary events, historians face the challenge of explaining the speed and ease of the Arab conquests, and it is natural to look for at least a partial answer in the state of the eastern provinces in the immediately preceding period. But a vibrant economic life has been revealed in recent work on the eastern provinces, and this, and the emergence of new approaches to Byzantine and early Islamic archaeology, have made the Near East in the sixth to eighth centuries one of the most fertile current areas of study. To that must be added a striking upsurge of interest in linguistic change and in the religious complexities of the region in this period. Chapter 9 will consider the Persian and Arab invasions, the situation of Jews in Palestine and elsewhere, and the religious conflicts of the seventh century which were felt in Palestine and Syria just as the Arabs armies arrived. The present chapter will be concerned with broader questions of settlement, the mix of languages, cultural expression and religion in the east, and the tense situation on the frontier and in these borderlands between Rome and Persia in the sixth century which led to the renewal of war between Byzantium and Persia and the successful Persian invasion of the early seventh century. The latter events, which ended with a great and unexpected victory for the Byzantines under the Emperor Heraclius, but were followed almost at once by the incursions from Arabia which we know as ‘the Arab conquests’, will be discussed in Chapter 9.

Settlement and Population

To what extent were long-term changes already taking place in the demographic structure of the east, the mix of ethnicities, and the relation of town to country, in the period before the seventh-century invasions? One striking feature is the progressive reliance of both Byzantium and Persia on Arab groups who based themselves not in cities, the traditional centres of Roman/Byzantine culture and the location of most of the army units in the later empire, but rather in desert encampments. The Ghassanids or Ghassan, with their ruling Jafnid elite, would congregate at the pilgrimage centre of St Sergius at Resafa or, it has been argued, at the shrine of John the Baptist at er-Ramthaniyye on the Golan Heights, while the pro-Sasanian Lakhmids, led by the Nasrids, had their base at al-Hira in modern Iraq. The earliest Arabic inscriptions use Aramaic script, but by the sixth century Arabic language and Arabic script were slowly coming into use alongside Greek, and church patronage by al-Mundhir is mentioned in the Syriac Letter of the Archimandrites of 569/70.1 Kinda were another major Arab grouping, occupying large tracts of central Arabia in the fifth and sixth centuries; they were remembered as ruling a ‘kingdom’ in later Arabic sources, but were in fact clients of the south Yemeni state of Himyar (see below). Al-Harith (Arethas) the Kindite concluded a peace with Byzantium under Anastasius, and according to one account his descendant Kaisos received an embassy to the Ethiopians (as the new rulers of Himyar), Amerites and ‘Saracens’, headed by the historian Nonnosus, probably in 531, according to a summary preserved by Photius in the ninth century; both Arethas and Kaisos are called phylarchs, and Kaisos was being pressed by Byzantium to intervene against Persia. Two Sabean inscriptions confirm the domination of Himyar in central Arabia.2 The presence of Arabs (‘Saracens’) both within and on the edge of Roman territory in the east had been familiar since the fourth century and before, and some had been Christianized at an early date; but under patronage from both Rome and Persia these ‘federations’ acquired a new sense of influence and identity. In the case of Ghassan, their relationship with Constantinople suffered a blow in the late sixth century when al-Mundhir fell from favour; eventually, however, both the pro-Roman and the pro-Persian groups gradually became Muslim.3 During their period as Roman or Persian clients, both the Ghassanids and the Lakhmids were Christian, the Ghassan being Miaphysite, the Lakhmids becoming Nestorian when their king, Nu’man, converted in the late sixth century. The luxury of the Ghassanid court is remembered in Arabic literature, and their transition to Islam and absorption into the Umayyad state is a key question, though it is unlikely that they were patrons of the so-called ‘desert castles’ in the area, as has been argued.

At the same time a different phenomenon is emerging with increasing clarity in recent scholarship, namely the high density of settlement in certain areas from the late fifth century into the sixth. This is true of certain parts of southern Palestine, the Golan and especially the Negev, which reached its highest density of settlement, and presumably of population, at this point (Chapter 7). The villages of the limestone massif of northern Syria studied by Tchalenko, Tate and many others since (Chapter 7), also testify to a prosperous and dense habitation, and to intense cultivation in the hinterlands of Antioch and Apamea. For once we also have evidence from papyri from Nessana in the south-west Negev, as well as archaeological evidence from urban centres such as Rehovot in the central Negev,4 Oboda and Elusa, which also developed during this period, to set alongside the results of surveys. There is plentiful evidence of viticulture and olive-growing, as well as material evidence of elaborate irrigation methods for agriculture in this dry region, such as dams, aqueducts, cisterns and the like. The comparison with modern techniques for cultivating arid regions such as the Negev is very striking, although conclusions can be premature. Interestingly, the towns of this period in the Negev seem to have been more market and administrative centres for the surrounding countryside, which was thickly dotted with villages, than urban centres on the late classical model.

A similar pattern of settlement density can be traced in other ways. The impressive number of mosaic pavements surviving from churches, synagogues and other buildings from this period in Palestine demonstrate the level of investment in buildings, even if not general prosperity. The large city of Scythopolis (Bet Shean) shows no sign of declining until the city was hit by earthquake, probably in 749 (Chapter 7), and a bilingual balance from the city, inscribed in Greek and Arabic, seems to suggest that the local population had found a modus vivendi with the new elite of the Umayyad period, while a Greek inscription of 662 from Hammat Gader, on the east coast of the Sea of Galilee, uses dating by both the regnal year of the caliph Mu‘awiya and the era of the former Greek city and Roman colony of Gadara. Reliable stratigraphy from excavation, which would yield better dating indicators, is admittedly often lacking, and surface finds may prove misleading. Yet population growth, development of towns and increased levels of cultivation and irrigation have been widely noted, not only in the Negev, but also in northern Syria and the Hauran. In contrast, there seems to have been a distinct falling away in many cases from the seventh century onwards, when, besides the effects of plague, the civil war under Phocas and the later invasions must also have taken their toll, together with a degree of emigration to the west. Some of the smaller and more remote of the many monasteries and hermitages in the Judaean desert seem to have fallen out of use in the seventh century, like the monastery of Khirbet ed-Deir, a cliff-side coenobium built in a linear fashion like those at Choziba, Spelaion and Theoctistus, though the large central ones survived into the Islamic period; a major factor in the reduction in number was the eventual disruption under new conditions to the impressive economic and market system which had previously enabled them to flourish so spectacularly.5 All this precludes any straightforward equation of military investment with prosperity, and raises the question of how to explain the demographic increase.

Many, though not all, scholars have seen a downturn setting in before the seventh century.6 This is still debated, and it is better not to imagine that there was a single unified late antique economy, even within the more prosperous east. Opinions vary, for instance, as to how much the Sasanian occupation of Himyar in the 570s affected Byzantine maritime commerce in the Red Sea,7 and there was variation even within specific areas such as the limestone massif or the area around the Judaean desert monasteries (below).

Map 8.1 The east in the sixth century

Various reasons have been put forward for prosperity in the east, among them the economic benefits of the pilgrim traffic (which included pilgrimage from Mesopotamia in modern Iraq, to the shrine of St Sergius at Resafa).8 This was certainly helpful to the region, and had been so since the fourth century, but it cannot bear the weight that has sometimes been put on it. Similar patterns of increased population density are in any case observable elsewhere, for instance in Egypt. In the case of Palestine and Syria recent explanations look to long-distance trade as a major factor in understanding the changes in the region over the period; shipwreck archaeology based on finds off the coast of Israel is one indicator of the density of exchange in the sixth century, and of a falling-off in the seventh.9

Long-distance movement of commodities in connection with the annona has been much studied in recent years through the evidence from amphorae, and even though its main axis in the later part of our period was from Egypt and North Africa to Constantinople, it is now clear that other goods travelled in all directions, and that Palestine and Syria were producing not only olive oil but also wine on a large scale, amounting to a substantial surplus and source of local prosperity. Not only shipwreck evidence but also literary sources such as the seventh-century Life of John the Almsgiver, patriarch of Alexandria, show that early Byzantine ships were involved in extensive distribution networks across the Mediterranean and to and from the east, carrying a wide range of items from metalwork, glass and silverware to spices and perfumes. Cargoes of specialized items probably also made use of the annona ships on their return journey having delivered their original cargo. A classic example of private trade is provided by the sixth-century traveller and merchant known as Cosmas Indicopleustes (‘he who sailed to India’), who described trading voyages to Ethiopia, the Red Sea, India and Sri Lanka in his Christian Topography,10 but the material evidence tells a fuller story of long-distance and local exchange and the interaction of state and private.11 This picture of extensive non-state production and distribution in the eastern provinces differs from that in the west, where the state-led annona accounted for a higher proportion of distribution, and it also reflects a different kind of settlement pattern, more urbanized and with more small producers still doing well, but fewer large estates.12 Egypt, with its great landowning families, is indeed an exception to this pattern, though the interpretation of the evidence is controversial.13 It ought to follow that the east was less affected when the annona ceased in the early seventh century, except that that coincided with the invasion and occupation of most of the east by the Persians; very little is known, however, about the actual impact of Persian rule (Chapter 9).

Older explanations for the prosperity of Syria and Palestine also appealed to the caravan trade which had been of major importance in accounting for the prosperity of Palmyra in the early empire, as we know from ample documentary evidence; the city suffered a decline when the rise of the Sasanian empire made free passage difficult, but eight churches are now known from late antique Palmyra, one of them a very large basilica of the sixth century and at least one a church built in the Umayyad period.14 To take a further example from the north of the area, Sergiopolis (Resafa), the main Ghassanid centre, north-east of Palmyra, was not only a major religious site, the focus of pilgrimage to the shrine of St Sergius, but was also located on a major caravan route which made it an important site of fairs and markets as well as religious gatherings. Finally, it has long been supposed that it was trade that gave Mecca its importance in the lifetime of Muhammad; this has been vigorously questioned, but reasserted in recent scholarship based on archaeological evidence (albeit limited).15 But as far as the eastern provinces are concerned, the caravan trade was only one contributor to regional prosperity in the sixth century when set against the broader picture revealed by amphorae and local archaeological evidence.

Constantinople in the sixth century was keen to build a wide sphere of influence among the kingdoms on the eastern fringes of the empire, and trade was certainly a factor in this.16 In the early sixth century Yusuf, who had made himself king of Himyar (south Yemen), adopted an aggressive Judaism in a context of competition between Jews and Christians and of complex relationships with Byzantium and Axum, and took the opportunity to persecute Christians, including Byzantine merchants; expeditions were launched to remove him from Ethiopia (Axum), whose interests coincided with those of Constantinople. Byzantium was eager to maintain access to the southern trade route to the Far East, and concern for trade with Ethiopia and Arabia thus played a major role in Byzantine diplomatic relations with Axum and south Yemen in the early sixth century.17 It is not surprising, then, that the controlled passage of merchandise was a major feature of the important treaty between Rome and Persia of 561; the third clause reads,

Roman and Persian merchants of all kinds of goods, as well as similar tradesmen, shall conduct their business according to the established practice through the specified customs posts.

(Menander, fr. 6, Blockley, Menander the Guardsman)

Silk was a particularly desirable commodity, and had been available to Byzantium only through Persia. According to Procopius, the (unsuccessful) Byzantine embassy to the Ethiopians in 531 offered them control of this trade as an inducement. However, according to a probably fanciful story also told by Procopius, Justinian later acquired some silk-worm eggs from Serinda, around modern Bokhara and Samarkand, allegedly in 552, with a group of monks as intermediaries.18 Silk was become one of the most prestigious materials in elite Byzantine and medieval culture thereafter, and this story itself is indicative of the complex amalgam of military, diplomatic, religious and trading interests that went to make up Byzantine–Persian relations in the sixth century.

Arabs in the Near East before Islam

The Arab federates were not merely military allies of the great powers (Chapter 9); they also acted as local patrons and influenced both religious and economic life. At Resafa again, a meeting point for semi-nomadic Arab pastoralists, a building traditionally identified as a praetorium, though decorated ‘within the standard repertoire of fifth- and sixth-century church decoration’, bears an inscription commemorating al-Mundhir, phylarch 570–81, with a standard Greek acclamation familiar from many inscriptions and graffiti: ‘the fortune of al-Mundhir is victorious’, or ‘Long live al-Mundhir!’19

This al-Mundhir usefully held off attacks from the Arab allies of the Persians until he fell in 581 to long-standing imperial suspicion; it is interesting to find that an earlier stand-off between him and the emperor in Constantinople had been settled in 575 by an exchange of oaths at the tomb of St Sergius.20 A complex balance existed in these regions between pastoral Arabs and monastic communities. We have already seen that there is a reference to a ‘church’ of al-Mundhir in the letter signed by 137 heads of anti-Chalcedonian monasteries. Such Arab influence could also make itself felt very directly, as when in the fifth century another Arab leader called, in Greek, Amorkesos (formerly subject to the Persians), had gained control of the island of Jotabe, possibly in the Gulf of Aqaba:

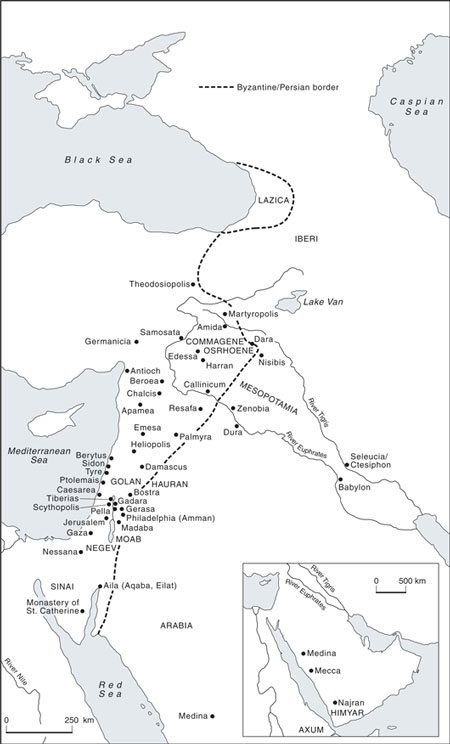

Figure 8.1 The so-called ‘praetorium’ at Resafa

[He] left Persia and travelled to that part of Arabia adjacent to Persia. Setting out from here he made forays and attacks not upon any Romans, but upon the Saracens whom he encountered. He seized one of the islands belonging to the Romans, which was named Jotabe and, ejecting the Roman tax collectors, held the island himself and amassed considerable wealth through collecting taxes. When he had seized other villages nearby, Amorkesos wished to become an ally of the Romans and phylarch of the Saracens under Roman rule on the borders of Arabia Petraea.

(Malchus, fr. 1, Blockley)

The enterprising Amorkesos now sent Peter, ‘the bishop of his tribe’, to put his case to the Emperor Leo, who was not only persuaded, but invited Amorkesos to Constantinople, entertained him to dinner, presented him to the senate and gave him the title of patricius, much to the disapproval of the historian Malchus who tells the story. When Amorkesos left, the Emperor Leo gave him gifts and public money from the treasury, and he in return presented the emperor with ‘a very valuable icon of gold set with precious stones’. The story shows very well the role played by Christianization in Byzantine diplomacy, as well as the techniques used to control border territories and manage local groups. At the end of the fifth century, however, Jotabe was recaptured by the governor of Palestine.21 Also in the fifth century a certain Aspebetos, a pagan and a Persian subject, converted to Christianity after his son was healed by the monk Euthymius, and made Euthymius’ monastery the centre of an ecclesiastical complex and tented settlement for Christian Arabs. Euthymius then requested and obtained the appointment of a bishop from the patriarch of Jerusalem, and with the patriarch’s consent, Aspebetos was ordained bishop to care for these ‘encampments’.22 ‘Saracens’ also appear in Cyril of Scythopolis’s Life of St Sabas both as the grateful recipients of Sabas’s charity and as potential raiders on Christian monks; in the latter story, set in the wild area to the west of the Dead Sea, the prayers of the monks were answered when a chasm opened up in the earth and swallowed up the ‘wicked barbarians’.23

The extent to which there was as yet an Arab self-definition is controversial. The epigraphic evidence is sparse, but an earlier and famous inscription from Nemara in southern Syria, dated to 328, and written in Arabic but in the Nabataean Aramaic script, is one of a small number of examples where Arabic is used. A certain Imru’ al Qays describes himself in it as ‘king of all the Arabs’ (the reading is certain, if not the interpretation: the term could be geographical rather than ethnic). The term ‘king’ is also found in relation to the Lakhmids and Tanukh and the term ‘Arab’ was used by the Romans; for instance, in Justinian’s Novel 102, which refers to the province of Arabia as ‘the region of the Arabs’. There are a few examples from the sixth century of inscriptions in Arabic script, and the linguistic situation was clearly changing, a development in which the Ghassanids may have played a role. Drawing on this evidence and on the role of the Ghassanids in later Arab historical memory, Robert Hoyland has proposed an emergence of Arab identity in the pre-Islamic period on the lines of the ethnogenesis theory applied in the case of such groupings in the west (Chapter 2).24 The Arabic sources also preserve a memory of heroic pre-Islamic poetry and aristocratic lifestyles. Arabic was becoming more widespread by the late sixth century, as seems to be indicated in the extraordinary cache of sixth-century papyri found in a room of the Petra Church at Petra in southern Jordan in 1993 (the very year when the first edition of this book was published), which consists of local documents written in Greek, as the accepted language of formal dealings, but evidently by people used to using a form of pre-Islamic Arabic.25 This discovery, which includes a large number of texts dating from at least 513–592, has transformed not only the history of Petra as known hitherto, but also that of landholding practice and economic activity in the region, and of language use in the sixth century. Most are private documents, and record land transactions or wills, with donations to local churches or monasteries, made by all kinds of local people, many of whom bear civilian or military honorific titles, and who have Nabataean or more commonly Greek names, or both: one document records the marriage settlement of Theodoros, the son of Obadianos. The better-off among them own more than 50 hectares of land and lease some out to be worked by others, producing wheat, grapes and fruits. They used Arabic to name parts of their property, and in some cases the names are very close to those in use in the area today. These sensational papyri from Petra stand alongside the papyri from Nessana in the Negev discovered in the 1930s; however, the latter also contain literary material, including a Latin/Greek glossary of Virgil’s Aeneid, and cover a later period, testifying to the continuance of a form of classical literary culture even into the Islamic period.26

Local Cultures, Language and Hellenism

Thanks to the scholarship of the last two decades, the social, cultural and linguistic history of the Near East in late antiquity, not to mention its religions, can now be seen as immensely fluid. The language situation alone is described by Fergus Millar as an ‘interplay of Greek with Semitic languages, whether Hebrew or various branches of Aramaic (Nabataean, Palmyrene, Jewish Aramaic, Syriac, Samaritan Aramaic, Christian Palestinian Aramaic (CPA)), with Egyptian (hieroglyphic, demotic or Coptic), with the languages and scripts of pre-Islamic Arabia, and finally with Arabic.’ In the same volume Robert Hoyland tentatively includes this phenomenon within ‘an efflorescence of a whole range of languages and scripts across the Roman Empire’.27 Millar has insisted forcefully on the dominance of Greek as the accepted public and formal language of the eastern Roman empire (despite the continued use of Latin in certain contexts),28 but in the Near East this was also a period of language formation, both oral and written, in which there was a wide range of language use and experience, from resort to paid translations up to (though probably not often) actual bilingualism.29 But language and identity did not necessarily go together, let alone imply ethnicity, and indeed it is hard enough to clarify the development and inter-relation of the various languages and scripts known from the area, especially as our evidence is so unevenly spread. Syriac, the form of Aramaic from the region round Edessa, was unusual in that it became an important literary language during late antiquity, being used for many works of Christian theology and other kinds of Christian writing. An increasing influence of Greek can be seen in the Syriac writings of the sixth and seventh centuries, and there were many translations from one language into the other, especially of saints’ lives and apocryphal works; many works circulated in several versions – Greek, Syriac, and sometimes Armenian, Georgian or, later, Arabic. However, few writers deployed both languages equally well themselves (they included bishop Rabbula of Edessa and his successor Ibas, both in the fifth century). Whether the use of Greek implies any kind of conscious Hellenism is hard to say. Funerary inscriptions from the Golan and from modern Jordan, for example, indicate that Greek was still in widespread use by individuals up to the seventh century, and many churches, including the fine churches at Jerash (Gerasa) in the so-called Decapolis, whose other cities included Philadelphia (modern Amman), were decorated with mosaic inscriptions in Greek verse as late as the middle of the eighth century and after. A mosaic with inscription in Greek from Umm er-Rasas (Kastron Mefaa), east of the Dead Sea and some 56 km south of Amman, dates from 718, though it has also been dated much later, and further construction, again with an inscription in Greek, in the same church is dated as late as 756. A range of the most important cities of the region are all named and depicted in mosaic, and from the sixth century we also have a mosaic map of Jerusalem itself in the church of St George at Madaba. Sophronius of Damascus, the future bishop of Jerusalem (d. 638), was able to compose poems in learned Greek verse to express his grief at the Persian conquest of Jerusalem in 614,30 and the Nessana papyri show that a mastery of Greek was still thought desirable in much more remote places. Greek also continued to be the language of the Chalcedonian church in Jerusalem, and this continued in the Melkite church in the Islamic period. Similar questions surround the continued use of classical architectural forms and especially of classical iconographical themes, which continued to be used even in sixth-century and later church contexts in Jordan.31

These questions of language history have recently been studied, particularly in relation to documentary and epigraphic evidence as indicating history ‘on the ground’. Similar issues arise in the increased use of Coptic in Egypt and its relation to Greek, and can be seen clearly in the very large numbers of Egyptian papyri.32 In Syria, one important type of such evidence is provided by the signatures in records of church councils or other ecclesiastical documents such as the so-called Letter of the Archimandrites of 569 (above, Chapter 7). But fluidity or interplay is also evident in intellectual and religious spheres. Greek philosophy had been read at Edessa long before the fourth century, and Greek learning also penetrated to the famous schools at Nisibis and Seleucia-Ctesiphon and, later, Gundeshapur. In the late fourth century the Syriac Christian religious poet Ephraem moved from Nisibis to Edessa when the former was ceded to the Persians in 363. His highly metaphorical and imaginative poetry may strike a classical reader as very unfamiliar, and he expressed a lively contempt for everything Greek, i.e., pagan; but his work was quickly translated into Greek, and a large body of other material also exists in Greek under his name, which was later much cited in the Greek monastic literature. On the other hand, the culture of an important bishop such as Theodoret, bishop of Cyrrhus in northern Syria in the fifth century, was Greek; he wrote in Greek and owed his culture to the traditions of Greek rhetorical education, writing letters to officials and churchmen in rhetorical Greek and many other Greek works, including a refutation of heresies, even though many of his flock knew only Syriac; how much Syriac Theodoret knew himself is less certain, but his Life of Symeon the Elder was one of three such works: two in Greek and one in Syriac (Chapter 3). The culture of the Syrian city of Antioch, the second city in the eastern empire, was also essentially Greek; it was the earliest home of Christianity outside Judaea and the centre of one of the two major Greek schools of theology and biblical interpretation. At Jerusalem the bishop always preached in Greek, but an oral translation into Aramaic was provided during the liturgy when the pilgrim Egeria went there in 384. Even at Edessa, the very home of the great Syriac literary tradition in late antiquity, Greek was in use till late in the Islamic period.

To say that Greek was the dominant language, necessary for official transactions, is true, but can be misleading in that it may obscure the very widespread use of Greek even in non-official contexts. It is even more misleading to use acquaintance with Greek as a badge of identity.33 The language of Jews in Palestine, for example, was Greek, and funerary inscriptions from the Golan and from modern Jordan, for example, indicate that Greek was still in widespread use by individuals up to the seventh century. Many churches, including the fine churches at Jerash (Gerasa) in the Decapolis, whose other cities included Philadelphia (modern Amman), were decorated with fine mosaic inscriptions in Greek verse as late as the middle of the eighth century and after. The administration and institutions of the empire placed an overlay of Greek on local conditions, but this had already been the case for centuries, since the foundations of Alexander the Great and the Seleucid empire that succeeded him. It is true that the literature in Syriac originated in a region considerably removed, and in certain ways very different, from the Hellenized coastal cities such as Caesarea, or indeed from much of Palestine, but distinctions between Greek and Semitic, whether applied to language or iconography, along ethnic or class lines can be very deceptive. An Arab dynasty ruled Edessa itself, and its affiliations can be clearly seen in the city’s reliefs and mosaics. Yet the same city produced a third-century mosaic of Orpheus as well as a Syriac inscription. At Palmyra, with a bilingual culture in Greek and Palmyrene, the temple of Bel proclaims its Semitic roots, though like the cella of the temple of Ba’al Shamin, it was converted into a church.

The culture of the Near East in late antiquity was a mosaic which can only be interpreted by reference to local differentiation. In north-eastern Arabia, Aramaic appears from the second century BC onwards, and ‘Nestorian’ Christianity was well established there in late antiquity, with Syriac as its liturgical language;34 there were also many Nestorians in south-eastern Arabia (Oman) when the area was under Sasanian rule before the Arab conquests.35 Again, while Syriac was the main written language of the Persian Nestorian church (the Church of the East, for which see Chapter 9), Arabic was the spoken vernacular of the Christians in Arabia. The difficulty remains of matching modern notions of ‘Arab’, ‘Syrian’, ‘Semitic’ and other such terms, which are still entangled in a mesh of confusion and even prejudice, with the actual situation in our period. But what seems to be observable in late antiquity is a heightened awareness of and readiness to proclaim local traditions, with a consequent increase in their visibility.

In this context the application of the concept of Hellenism is much more difficult. Greek continued to be used as a literary language, and there is a huge volume of theological, hagiographical and other writing from the sixth and seventh centuries. The controversial bishop Severus of Antioch wrote in Greek, though his works survive in Syriac; Gaza was the centre both of monasticism and of a highly sophisticated Greek literary culture in the early sixth century,36 while Procopius the historian came from Caesarea in Palestine. The monastic author Cyril of Scythopolis composed biographies of Palestinian monks, and the later writers John Moschus, Sophronius, Maximus Confessor and Anastasius of Sinai, all writing in Greek, were monks in the region.

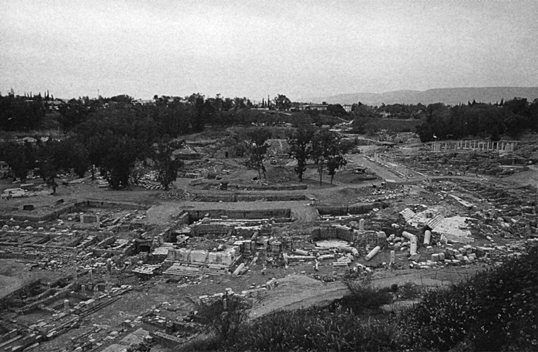

Figure 8.2 The city of Scythopolis (Bet Shean), birthplace of the sixth-century monk and hagiographer Cyril of Scythopolis and other learned theologians. Scythopolis remained a flourishing city throughout the seventh century and into the eighth.

This Greek intellectual culture continued after the transition to Islamic rule, with the production of chronicles, saints’ lives, apologetic works and many more; John of Damascus himself wrote in this tradition in the eighth century and the same period saw the creation of a great tradition of Greek hymnography. Much of this output presupposes the availability of a high level of traditional education, even if some of these writers also at times exploited the old but useful trope of the opposition of classical, i.e. pagan, culture to Christianity. Given such a context, including of course the role of Greek as the language of official and legal dealings, it is not surprising that it should have continued to be the language of government and bureaucracy under the Umayyads. The shift away from Greek that only becomes apparent in monasteries in the early ninth century reflects the move to Arabic that accompanied the change from Umayyad to Abbasid rule.

Figure 8.3 The large refectory of the monastery of Martyrius in the Judaean desert near Jerusalem. The monastery was built in the late fifth century but the refectory dates from a century later. The modern building belongs to the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim.

In art and iconography, we have seen that classicizing motifs and styles were freely used and if necessary adapted, often in very striking ways.37 But whether contemporaries themselves had any concept of Hellenism is another matter entirely.

Jews and Judaism

A substantial Jewish presence and corresponding Jewish influence are features of this area in Palestine itself and also more widely. In southern Arabia a substantial body of epigraphic material has shown that between 470 and 493 the kingdom of Himyar adopted a strongly monotheistic religious stance; Jews are attested in the fourth century and Jewish inscriptions begin in the fifth, with Christians also making an appearance. The kingdom came under direct Christian influence when after the episode at Najran it was subject to Axum, but it had already had a bishop in the reign of Anastasius38 the presence and influence of both Jews and Christians in Arabia at the time of Muhammad provides an important context for the emergence of Islam (Chapter 9). The Babylonian Talmud emerged over a period of centuries within the Sasanian empire, and eventually overshadowed its Palestinian counterpart, and the Jewish diaspora is attested all over the eastern empire in synagogues and inscriptions. In Palestine itself a considerable Jewish population existed in the sixth century and on the eve of Islam, centred on Galilee and the Golan and with Tiberias as its main intellectual and religious centre. Some synagogues went out of use by the mid-sixth century, but many others continued to function until the early seventh century. We have already seen the astonishing richness of synagogue mosaics, which are still being revealed and interpreted, and this indicates a confident Jewish life in the context of the increasing pre-ponderance of Christians. Nevertheless imperial legislation was becoming more intolerant by the sixth century. It has been suggested that the growing influence of imperial Christianity acted as a stimulus to others to crystallize their own religious identity. In the words of Seth Schwartz, ‘Jewish life was transformed by Christian rule’; he goes on, ‘the Jewish culture that emerged in late antiquity was radically distinctive and distinctively late antique – a product of the same political, social and economic forces that produced the same no less distinctive Christian culture of late antiquity’.39 The development began with the imperial support for Christianity adopted by Constantine, which entailed a new attitude to contemporary Jews, as inheritors with Christians of the religious past of both religions, albeit having taken the wrong track. Constantine’s successors were at the same time protective and restrictive in their approach, but gradually became more and more controlling. The Jewish patriarchate had been first limited in 415 and then abolished, and Justinian’s legislation on the subject of Jews is distinctly negative. His Novel 146 (issued in AD 553) prescribed the languages that should be used for synagogue readings, preferring the Septuagint translation for Greek, though commending that of Aquila on the grounds that it was the work of a gentile; the law makes clear that Judaism is in error and needs ‘correction’. The broader context here is that of a return to the use of Hebrew among Jews in the sixth century, both in the diaspora and in Palestine, as well as an actual variety of Jewish language practice across the empire.40 As the Christian empire became more repressive, Jews were classed alongside heretics and pagans in legislation, and even more forcefully in a mass of Christian writing. This trend led eventually to an enactment by Heraclius in the seventh century requiring all Jews to be baptised; this was repeated by Leo III in the eighth and Basil I in the ninth century, though it was a product of heightened animosity and resentment at the time and could hardly have been enforced (Chapter 9).

The Samaritans, with their centre on Mt Gerizim, where the Emperor Zeno built a church of the Theotokos on the site of their sacred precinct, were also subject to imperial repression, and rose up repeatedly in the fifth and sixth centuries; the uprisings were harshly put down, and Procopius claims that Justinian ‘converted the Samaritans for the most part to a more pious way of life and has made them Christians’.41 Jews had been the subject of hostility, and Judaism the target of stylized refutation in Christian apologetic writing, since as early as the second century, and were often depicted as malevolent and dangerous in saints’ lives and other kinds of Christian writing. This tendency intensified as time went on, and reached a peak in the period of the Persian and Arab invasions, when Christian writers blamed the Jews of Palestine for helping the invaders and participating in the killing of Christians.42

Yet this increasing Christian pressure coincided with an efflorescence of Jewish life and, it would seem, of Jewish self-confidence, especially in Palestine. Jews appropriated many aspects of imperial Christianity and made it their own. Fifth-century Palestine was transformed by the building not only of large numbers of churches but also of synagogues, their decoration showing close parallels with Christian art (Chapter 7). Those who built them and worshipped in them ignored imperial prohibitions on building synagogues and clearly did not expect to suffer as a result.43 Nor did they seem to have qualms about representational art, though this was to change. The flourishing Jewish life of Palestine was part of what Glen Bowersock calls the ‘kind of miracle’ of the late antique Near East, the Sepphoris synagogue a ‘polyglot marvel, with inscriptions in Aramaic, Hebrew and Greek’44 – though it was indeed a linguistic variety shared in many quite different and non-Jewish contexts. As we saw, late antiquity was also the period when the Palestinian and Babylonian Talmuds reached their final stages. However, the influence of the rabbis on everyday Jewish life, assumed in past scholarship, now seems much less evident (the parallelism with revisionist views of the actual impact of late Roman imperial legislation is obvious); Jews wanted to be distinctive, but they were also willing to adopt cultural expressions from wider society.45 This did not protect them from occasional outbreaks of active Christian hostility, as had happened in the context of the arrival of relics of St Stephen on the island of Minorca in 417,46 and many Christian bishops made it their business to stir up Christian suspicion. The attitudes of Christians towards Jews in Palestine also hardened, especially under the pressures of the seventh-century invasions, although much of this was expressed at a literary level. A corresponding process of increased Judaization has been seen by Seth Schwartz in synagogue art and in the emergence of the Hebrew poetic form of piyyutim, with its close relation to the rabbinic corpus;47 this can be seen in turn as part of a resilience which meant that the Jewish presence survived the transition to Islamic rule, with Tiberias continuing to be a centre of Jewish learning and religious life under early Islam.48 If true, this may also have been a contributing factor to the intense anti-Jewish rhetoric found in seventh-century and later Christian sources on the Persian and Arab invasions.

While the diffusion of synagogues in fifth- and sixth-century Palestine is indicative of a thriving village network, the same period saw extensive church building. How far Jews and Christians at this period tended to live in separate communities is a matter of controversy,49 but village synagogues, like village churches, indicate the presence and willingness of donors to contribute on a large scale; as with donor inscriptions in churches, the economics of their construction were recorded, as at Bet Alfa and synagogues had treasuries. But the region was also the home of ascetics, some very famous and much-visited.

The Appeal of Ascetics

In the late fourth and fifth centuries prominent westerners including Jerome and his friend Paula, who settled at Bethlehem, and the Younger Melania and her husband Pinianus travelled to the Holy Land and Melania founded a monastery on the Mount of Olives monasteries; the Empress Eudocia, wife of Theodosius II, travelled there with Melania in 438 and lived there for some years after 443. We have already encountered the stylite Symeon the Elder (d. 459) with his pillar at Qalaat Semaan in Syria (Chapter 3), and more than a century later, Symeon the Younger (d. 594), whose pillar was located outside Antioch on the so-called ‘Wondrous Mountain’, began his ascetic life by attaching himself to the community that had grown up around another stylite. According to his Life he was well informed about events in Antioch, knew of the death of the Lakhmid al-Mundhir in 553 and predicted the succession of Justin II in 565. Famous holy men like these were well connected and enjoyed elite patronage. They were very different from some of the ascetics who were the subjects of Theodoret’s Historia Religiosa in the fifth century, some of whom practised exotic forms of personal abnegation such as living in cowsheds and eating grass.50 Monasticism depended on ascetics; as we have seen, Cyril of Scythopolis in the sixth century also wrote of Euthymius and Sabas, monastic founders who were themselves ascetics, and the Judaean ‘desert’ was full of monasteries large and small, as well as hermitages and caves inhabited by individual holy men. The region was also the location for more fanciful stories about female ascetics who were repentant prostitutes and who disguised themselves as men in the ascetic life; particularly well-known examples are Pelagia, according to the story a courtesan from Antioch in the late fourth century, and Mary of Egypt, whose story is known in Latin in the sixth century, and who was said to have came originally from Alexandria to visit the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and subsequently lived for many years in male disguise on the banks of the Jordan. Many versions of the story are known, including a Greek version attributed to Sophronius.51 These are monastic stories, and John Moschus, who travelled with Sophronius and died in Rome in 619, was another Palestinian monastic writer in the late sixth century who collected anecdotes about such ascetics in Egypt, Palestine and Sinai in his Spiritual Meadow. Egypt, Palestine and Syria were thickly populated not only with monasteries but also with individual ascetics who spent long periods travelling or living in remote and difficult places; however, despite the ideology of isolation they were not totally cut off, and a delicate balance was preserved between the solitary life and interaction with others.

A sixth-century text which gives a vivid impression of monastic life in the area around Amida is John of Ephesus’s Lives of the Eastern Saints, already referred to in Chapter 7, and indeed the ascetic ecosystem of the Near East in late antiquity is very well documented. It continued beyond the Arab conquests, and extended into Mesopotamia and regions further east in what is now Iraq. It also transcended language barriers; works were translated from and into a variety of languages – Greek, Syriac, Georgian, Latin, Arabic – which must be a sign of their extreme popularity, and of the vigour of the ascetic ideal, whether in living or historical examples or in stories. It was an ideal that found expression in the building and occupation of many monasteries, and which exercised a powerful effect on the minds and imagination of contemporaries. Over and above their personal ascetic struggle, these holy men and women played many roles in relation to their milieu. Some were local mediators in village society, according to the influential model set out by Peter Brown forty years ago,52 others did live lives of near-total isolation, but others again were prominent leaders in their communities and beyond, or famous stars of the late antique world; we see the aged St Sabas in action in 518 when the decree came from Justin I to reinstate adherence to the Council of Chalcedon after the death of Anastasius, travelling to cities in the region, and later even to the court of Justinian, pleading the case of the church of Palestine after the damage done by the Samaritan revolt.53 Justinian responded with tax remission, gold, restoration of burnt buildings, erection of a hospital and a new church of the Theotokos in Jerusalem (known as the Nea and shown on the mosaic map of Jerusalem at Madaba), and a portion of the tax revenues of the province for the buildings of fortifications to protect Sabas’ monasteries. Eliciting patronage, including imperial patronage, and predicting the future, were just some of the essential gifts in the repertoire of such a holy man.

Church Councils and Religious Divisions

Monasteries and asceticism also crossed religious boundaries. The maintenance of Chalcedonian orthodoxy is a main theme in Cyril’s Lives. Euthymius is credited with bringing the independent Empress Eudocia back to orthodoxy, and had earlier instructed the bishop of the Saracens who attended the Council of Ephesus to follow Cyril of Alexandria and Acacius of Melitene in everything.54 It was part of the agenda of hagiography to insist on the right doctrine of its subject, and Cyril provides a list of the heresies opposed by Euthymius; Euthymius supported the Council of Chalcedon (451), and Palestinian monasteries remained centres of Chalcedonianism (and, after the Council of 553, ‘Neo-Chalcedonianism’), but Cyril’s narrative reveals both the extent of anti-Chalcedonianism and the risk from his point of view that this opposition might prevail in the province.55

The struggle on the ground between pro- and anti-Chalcedonians occupied monks and bishops in the east throughout the late fifth and sixth centuries and later; the eastern provinces on the eve of Islam are often represented as if they were uniformly anti-Chalcedonian, but Sophronius and Maximus Confessor were only the most prominent among the defenders of Chalcedonian orthodoxy in the seventh century in the very years of the Arab conquests (Chapter 9). The struggle involved local loyalties as well as relations with the imperial church. Bishops were required by the major councils to remove the names of those condemned as non-orthodox from the liturgical diptychs, as happened after the council of 553, but they also took independent action, and one of the central fields of dispute (and of confusion for ordinary people) was that of the sharing or denial of communion.56 Monasteries and bishoprics and their people were also split, or, as we have seen, changed their positions, but the key moment came with the ordinations of bishops for the anti-Chalcedonians, and then by them of further anti-Chalcedonian bishops. Some were consecrated in Constantinople and sent to Egypt, while others were given dioceses in other parts of the East but had to adopt an itinerant mode in the prevailing climate.57 The sympathetic Empress Theodora and the Ghassanid phylarch al-Harith are credited with having fostered this initiative. A new hierarchy was thus initiated and was to last through periods of repression and even persecution by the Chalcedonian government later in the sixth century. However, neither Syria nor Palestine were by any means wholly anti-Chalcedonian, and in some cities, including Antioch and Edessa, and indeed Alexandria, there were competing groups and rival bishops; naturally personal rivalries and local followings were also involved. Justinian and his successors in Constantinople went on attempting to square the circle, and Heraclius was still trying to do the same in the seventh century with a new initiative – Monotheletism. This was, however, bitterly opposed by Chalcedonians in Palestine and led to the imperial condemnation and eventual deaths of Pope Martin I and Maximus Confessor (Chapter 9). But there were also divisions among the anti-Chalcedonians, and these often expressed themselves most bitterly within a single city or even a single monastery.58 Anti-Chalcedonianism certainly had local manifestations and allegiances, but it cannot be maintained that it was a popular, ethnic or ‘national’ movement, and anti-Chalcedonian sentiment by no means coincided with Syriac Christianity. Throughout the reigns of Justin and Justinian the centres of the resistance were in Alexandria and Constantinople as much as, or even more than, they were in the Syrian countryside. It is not very surprising, however, if local interests started to turn the situation to their own advantage and claim the movement as their own, and one can see a powerful move in this direction in the energetic and extensive writing of men such as John of Tella.59 Christianity was also well established within the Sasanian empire. The ‘Nestorian’ or dyophysite tradition identified with the School of Nisibis was strong, but by the sixth century it was not universal, as is demonstrated by the activities of Ahudemmeh,60 and the treatment of Christians in Persia figured from time to time in Roman–Persian diplomacy in the late sixth century as it had since the time of Constantine.61 Christians in the Persian empire also included Miaphysites, especially in western Mesopotamia,62 and Christian discussion crossed political boundaries and spanned the territory of both empires. Public debates took place in Constantinople and Ctesiphon, under the patronage of both Justinian and Chosroes I, and also involved Manichaeans and Zoroastrians. East Syrian representatives were summoned to Constantinople in the early days of Justinian, and Chosroes held debates at his own court. Common themes were also debated in both places, such as the question of the eternity of the world, disputed by Christians, and debated also in sixth-century Alexandria, with Aristotelian logic as a shared technique.63

An enormous amount of documentation accompanied the councils and other meetings that attempted to settle the main christological and other divisions between Christians, and ranges from letters to individuals and dioceses to the formal acts of ecumenical councils. These documents are an invaluable source of information about the languages in use and the geographical spread of allegiances. A series of powerful articles by Fergus Millar has underlined the possibilities for the historian of this period in using this material.64 It was a requirement of formal church councils that those present should indicate their assent to the decisions taken by signing a final agreed statement, and sanctions normally followed for those few who refused. The signatures are an invaluable source in themselves and are very revealing about language, the geographical range of bishoprics represented and (with caution) identity, and it is only relatively recently that they are being fully exploited by historians of late antiquity.

The meetings with anti-Chalcedonian easterners held in Constantinople in 532 (the so-called ‘Conversations with the Syrian Orthodox’)65 were followed by Justinian’s own initiative in the 540s to condemn the ‘Three Chapters’; the fifth ecumenical council in 553 was called in order to try to deal with the resulting outcry (Chapter 5). Justinian’s successor Justin II and his wife Sophia attempted again to bridge the divide between pro- and anti-Chalcedonians, with an unsuccessful meeting at Callinicum, but persecution followed, as it did again in 598–99. This was fruitless and any effects were temporary. Heraclius held meetings at Dvin to try to win round the Armenians even as he was struggling to meet the assault of Chosroes II’s armies, and his Monothelete initiative in the 630s – yet another imperial attempt to win over the east – was met by hectic synodal activity in Palestine and Cyprus in which Sophronius was a major participant. The meeting known as the Lateran Synod held in Rome in 649, with prominent roles played by Maximus the Confessor and his supporters, was yet another powerful indicator of the extent of opposition to imperial policy. Its Acts, composed in Greek and only later translated into Latin, and written with heavy input from Maximus’s own writings, are an indication of the level of tendentiousness as well as the sheer energy that was involved (Chapter 9). Yet the various meetings and synods mentioned here are for the most part only the more public and official; there were also countless local meetings, all with their own extensive records, preparatory materials and what we would now see as pubic relations. It is not surprising to find that in the major councils of the late seventh and eighth centuries the authenticity of evidence and materials cited in the discussions was such a serious concern that measures had to be put in place to try to verify them; nor is it surprising that in many cases they have come down to us in redacted versions which sometimes pose difficult problems of interpretation.66

The Eastern Frontier

The study of the material remains of military installations in the east is an important factor in any consideration of the defence of the eastern provinces.67 It is also closely connected with the development of a revised conception of frontiers as zones of influence and ‘borderlands’ (Chapter 2),68 and with a better understanding of the relations between ‘nomadic’ and settled groups and of the use of local client forces. Nor does a frontier necessarily have to be linear: much of the very extensive building of fortifications under Anastasius and Justinian entailed building or strengthening garrison forts and fortifying cities well inside the conventional ‘frontier’.

The build-up of Roman forces in the east had begun with Trajan’s Parthian war of 106, which marked ‘the beginning of an obsession which was to take a whole series of Roman emperors on campaign into Mesopotamia, and sometimes down as far as Seleucia and Ctesiphon on the Tigris’.69 Under Septimius Severus in the early third century, two extra legions were created for service in the east, and five cities in the new province of Mesopotamia – Edessa, Carrhae, Resaina, Nisibis and Singara – were given the status of Roman colonies; eight legions were now stationed in the zone which stretched south from here to Arabia. Rome was soon faced with the strong military regime created by the Sasanians on its eastern borders and highly damaging incursions took place in the fourth century under Shapur I; Rome was obliged to make an expensive peace in 363 after the ill-fated Persian expedition of the Emperor Julian, and ceded to Persia the important border city of Nisibis.70 However, recent scholars have pointed out that for most of the period neither of the two empires seriously thought of trying to defeat the other or occupy territory on a large scale, and have argued that the Roman defence system was in fact much concerned with prestige, internal security and the policing of the border areas. Benjamin Isaac is not the only scholar to have argued that the military roads which are so conspicuous in this area, especially the strata Diocletiana, a road from north-east Arabia and Damascus to Palmyra and the Euphrates, and the earlier via nova Traiana, from Bostra to the Red Sea, were meant not as lines of defence, but rather as lines of communication. However, the need for an intensification of defences became acute when in the early sixth century the Persian shah Cavadh launched a major attack, with a damaging siege and capture of Amida in Mesopotamia in 502, vividly described in the Syriac chronicle attributed to a certain Joshua the Stylite.71 People in the area who had managed to escape the Persian assault were tempted to flee, but the Syriac author Jacob of Serug wrote to all the cities nearby urging them to stay.72 The same chronicle gives a striking picture, corroborated by Procopius’ accounts of the Persian wars under Justinian, of the leadership bishops in eastern cities now provided in matters of defence, building fortifications, pleading the cause of their city with the emperor and negotiating with the Persians. They were not always successful: Megas, bishop of Beroea (Aleppo), had the unenviable task of trying to negotiate with Chosroes I when the latter was threatening Antioch in 540 and the Byzantine troops were wholly insufficient to defend it. Chosroes took 2,000 lbs of silver from Hierapolis and demanded ten centenaria to call off an attack on Antioch, but attacked Beroea (Aleppo) and sacked it in any case, and went on to sack Antioch. Orders had come from Constantinople not to hand over any money, and the city’s patriarch, Ephraem, was thought to have favoured surrender.73 Defence needs also went hand in hand with pleas for reduction of taxation. In 505–6 the generals Areobindus and Celer reported to the Emperor Anastasius that the border near Amida and Tella was in need of strengthening in order to fend off Persian attacks; as a result, orders were given to fortify the frontier site of Dara, a project in which the bishop of Amida was much involved, as is known from the anonymous continuation of the Syriac ecclesiastical history by bishop Zachariah of Mytilene; Procopius later contrived to give the credit for the massive fortifications of Dara to Justinian.74 After the Persian assault on Amida the remaining population suffered badly from shortage of food, and the bishop went to Constantinople to plead with Anastasius for remission of taxes.75 During the Persian wars of Justinian, and especially in the difficult years in the early 540s when Belisarius clearly did not have enough troops, bishops were even more active in their attempts to buy off the danger of a Persian siege, usually with large payments of silver (Chapter 5).

In the Sasanians, the Byzantines faced a rival power which was their equal in military capacity and at times capable of ruthless and aggressive campaigns against Roman territory. We have seen already the helplessness of the eastern cities when faced with the armies of Chosroes I, as well as the financial cost of peace to the Byzantine empire (Chapter 5). Very large payments were made by Byzantium to Persia over the course of the sixth century, and there are indications that Justinian found it difficult to maintain sufficient troops on the eastern frontier; the annual payment of 500 lbs of gold agreed in the great peace treaty of 561 was a considerable burden on Byzantium, and the treaty did not prevent war from breaking out again between the two sides.76 Chosroes II (590–628) suffered a coup at home and owed his throne to the Emperor Maurice; he renewed the promise of freedom of religion to Christians within his kingdom who had been included in the peace of 561, and showed his attachment to the Christian shrine of St Sergius at Resafa with gifts when the saint answered his prayer that his Christian wife Shirin should conceive. Theophylact Simocatta records the long letter in Greek which the king sent to Sergius; Theophylact also tells how the king prayed before an image of the Theotokos carried by a Byzantine ambassador.77 Nevertheless he proved just as ruthless an enemy as Chosroes I had been. Years before, the ageing Cavadh had proposed to Justin I that the latter adopt his son Chosroes I and so guarantee the latter’s succession; this overture was taken very seriously on the Byzantine side and was formally discussed at a high-level diplomatic meeting on the frontier, but no agreement was reached; according to Procopius, who tells the story, the young Chosroes was deeply offended and vowed to make the Romans pay for this slight.78 In real terms relations between the two empires and their rulers involved a complex interplay of mutual interest, balance of powers and (at times) overt hostility. Conquest as such was out of the question on the Byzantine side, but the Persian invasions of the early seventh century departed from previous precedent. The Persians not only delivered near-fatal blows to many Roman cities in Asia Minor, and stimulated flight among the Christian populations, especially the monks and clergy, of Palestine and Egypt, but also actually occupied and ruled the Byzantine east – if only through proxies – for nearly two decades (Chapter 9).

The Roman empire attempted to control and influence vast areas of the east, over a great swathe reaching from the northern Caucasus around to Egypt and beyond. It could not do this by arms alone, and the interconnection of mission and defence in late Roman policy in the east is a constant theme. This can be seen very clearly in the empire’s dealings with the Caucasus, where the conversion to Christianity of Tzath the king of the Lazi under Justin I marked a deliberate departure from Persian clientship, and was correspondingly greeted with considerable pomp in Constantinople, including baptism, marriage to a noble Byzantine bride and the formal acceptance of a crown, Byzantine ceremonial robes of silk and many other gifts;79 not surprisingly this was taken very badly by Cavadh, and proved to be merely an episode in the complex struggle for control of Lazica by Rome and Persia. The Lazi chafed under Roman control and appealed again to Persia, which duly invaded in 541 and received the submission of Tzath’s successor Gubazes;80 however, they found the Persians no better, and Lazica found itself a theatre of war in the late 540s.81 Religion could be a useful tool for either side, but Byzantium was also committed to conversion, admittedly also potentially advantageous in diplomatic dealings, and the twin objects of conversion and defence are a theme of Procopius’s Buildings, in which the foundation of new churches went hand in hand, as conspicuously in the case of his account of North Africa, with military installations.

The differences between east and west are great, but the eastern provinces in the seventh century shared with the fifth-century west the experience of external threats and the dangers of internal fragmentation. Changes in urban and rural settlement, Christianization, the interpenetration of Greek with local cultures and the impact of the military and fiscal needs of the Byzantine state are all very evident well before the last great Persian invasion of the early seventh century and the arrival in Syria of the followers of Muhammad. The story of the origins and expansion of Islam itself fall outside the compass of this book. Yet when the Muslims left Arabia and encountered Roman troops in Palestine and Syria, they found the Roman Near East already in a ferment of change.