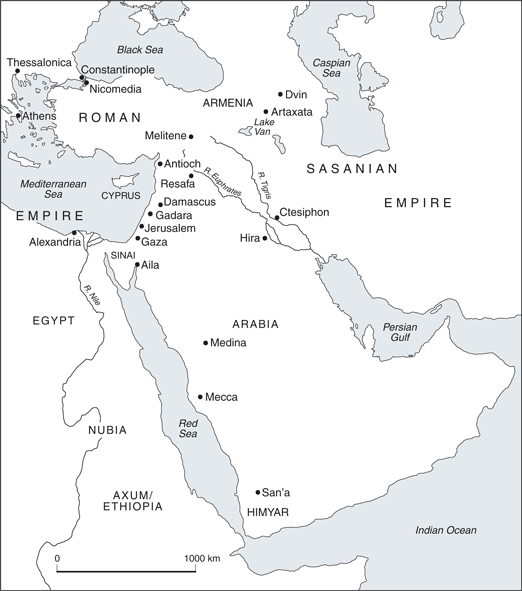

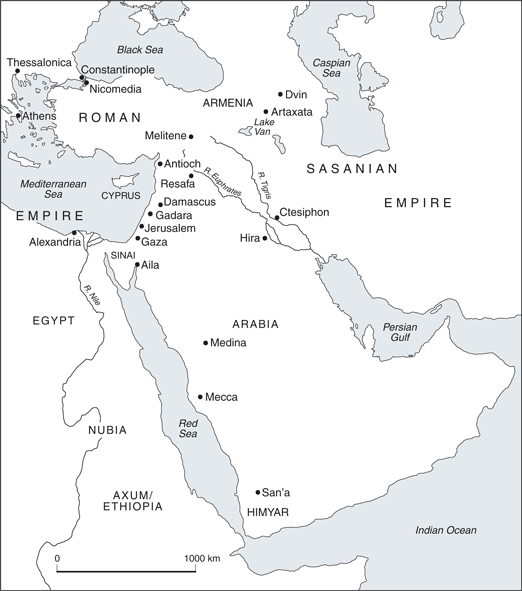

Map 9.1 The east in the early seventh century

9

Renewed War with Persia

The peace of 561 did not last. Despite the Emperor Maurice’s help to the young Chosroes II, the renewed war between Byzantium and Persia in the final years of the sixth century and the Persian invasion and conquest of Byzantine territory that followed in the early seventh century were devastating blows to the future of the empire. In 626 the Persians and the Avars joined in a siege of Constantinople that put the empire in a desperate situation and was very nearly successful, the Emperor Heraclius having taken the drastic step of leaving the capital to gather troops and to campaign.1 The situation was very dangerous, and even before the siege started there were angry protests in the city about the price and supply of bread. The city’s eventual delivery was ascribed to the intervention of the Virgin Mary:

[God] by the welcome intercession of his undefiled Mother, who is in truth our Lady Mother of God and ever-Virgin Mary, with his mighty hand saved this humble city of his from the utterly godless enemies who encircled it in concert.

(Chron. Pasch., p. 169, trans. Whitby and Whitby)

The Virgin had become more and more prominent in religious consciousness; she was depicted in apse decoration and panel paintings, and after the siege she was now described in the guise of a general leading the inhabitants of Constantinople to victory.2

Success against the Persians by Heraclius in 628 and his restoration of the True Cross to Jerusalem in 630 was followed closely by the Arab invasions and Heraclius’ decision to retreat from the east.3 Despite lurid accounts of destruction in the Greek and Syriac sources, recent archaeological research indicates that neither the Persian nor the Arab invasions in Palestine and Syria left much trace on the ground, at least outside Jerusalem and its environs,4 though the effects of Persian campaigns on Asia Minor cities such as Sardis may be a different matter (below). But the eastern empire ruled from Constantinople was greatly diminished; it only began to recover in the second half of the eighth century as a result of energetic imperial effort, and then in a form that was much changed in administrative and financial terms. It makes sense in many instances to see late antiquity as extending well into the Umayyad period, but this mainly eastern continuity should not obscure the drastic reduction and refocusing of the eastern empire which was also taking place. The ‘Arab conquests’ of the seventh century did not happen as quickly as the term suggests (though the early advance into Syria was dramatic), or without struggles and setbacks, but by the early eighth century the Mediterranean world was a very different place. The powerful Sasanian kingdom had fallen, and a new and powerful regime controlled the former Roman provinces in the east, Egypt and North Africa and much of Anatolia. Attempts on Constantinople, culminating in a potentially disastrous siege in 717–18, were repulsed. The Arabs failed in their hope of conquering Byzantium, but the emperors in Constantinople ruled a drastically reduced territory, the Muslims were already in Spain and the Mediterranean had become a dangerous place.5

Rome and Persia from Justinian to Heraclius

We are well informed about the new campaigns conducted against the Sasanians by Justin II (565–78), Tiberius (578–82) and Maurice (582–602), Justinian’s successors in the late sixth century, and about the final struggle between Rome and Persia in the years 603–30. In Greek, the history written by Menander Protector, which continued that of Agathias, is preserved only in fragments, but thanks to the interest in diplomacy shown by later Byzantine compilers, we have substantial sections relating to Byzantine–Persian relations under Justin II and Tiberius. The Histories of Theophylact Simocatta, written in the reign of Heraclius (AD 610–41), give a detailed account of the reign of the Emperor Maurice,6 and there is a wide range of other sources, from the Chronicon Paschale and later chronicles to the epic poems which George of Pisidia wrote about Heraclius’s wars. To these we can add a wealth of material in Syriac, especially chronicles, and the seventh-century Armenian chronicle attributed to the bishop Sebeos.7 The Persian conquest and occupation of Jerusalem in 614 is very well documented by contemporaries, and later Greek, Syriac and Arabic sources are all important, especially for the years that saw the early stages of the Arab conquests and the end of the Sasanian kingdom.8 This wealth of evidence is often difficult to use because much of it is fragmentary or written with a religious or partisan bias, while the problems surrounding the evidence for the early stages of Islam and the Arab conquests also give rise to extremely polarized positions among scholars. Not surprisingly, a huge amount of secondary literature has grown up, of which only the most important and the most helpful contributions can be referred to here. But again, this is a field in which there has been an explosion of recent scholarship, but also to which useful guides now exist.

Despite the ‘Endless Peace’ of 561, continuing grievances between the two powers emerged as soon as the usual embassy was sent to Chosroes after Justin II’s succession in 565, and the new emperor adopted the same aggressive and defiant stance he had shown when approached by Avar envoys in Constantinople9 and refused to accept what his envoys had agreed. Theophylact blames the emperor for the reopening of hostilities in 572, and a botched attempt at the assassination of the Ghassanid al-Mundhir and Justin’s willingness to accept the persuasion of the Turks to go to war with Persia suggest that he was right to do so. The ecclesiastical historian Evagrius and other writers were also highly critical, the historian John of Epiphaneia stating that the real reason for hostilities was Justin’s refusal to pay the agreed annual amount of gold according to the treaty. Justin’s stance encouraged the Persarmenians to leave the side of Persia and join Rome (offering silk as an inducement, according to Gregory of Tours), thereby provoking the Persians.10 The emperor’s poor judgement continued during the hostilities, according to hostile reporters, when he interfered disastrously with the leadership of his generals, and later Justin was to launch a persecution of Miaphysites and to lapse into insanity on hearing the news of the loss of Dara (573), so that Tiberius and Justin’s wife Sophia had to be given powers to rule. The result of this sorry episode for the Romans was that they had to pay a large sum and in addition agree a truce for five years with a very high level of annual payments.11

Chosroes took advantage of these gains to attack in Armenia, which fell outside the terms of the treaty, and then in Melitene, but was driven into retreat by Roman troops who were able to send Persian trophies (including war elephants) to Constantinople as a result.12 Talks were renewed, and agreement had been reached when the Persians again defeated the Romans and went on the attack in Mesopotamia. The Romans, under the general Maurice (emperor from 582) fought back, together with al-Mundhir and the Ghassanids, despite suspicions of the latter’s loyalty. The command passed to Philippicus, who defeated the Persians at Solachon in the Tur Abdin in 586, parading an image of Christ and the head of Symeon the Stylite which he obtained from Antioch.13

The two powers existed in an uneasy balance, with episodes of fighting and raiding alternating with short-term agreements, soon broken. Proxy war was also conducted between their respective clients, the Ghassan and Lakhm. Neither side won a clear or lasting advantage and the continuing warfare, which effectively lasted for over a century, was a serious drain on both sides, while cities, territories and the inhabitants of the contested areas were also losers. But the two powers also recognized each other’s role. When in 590 the succession of Chosroes II was opposed by Bahram Chobin, the Persian king turned to the Roman emperor Maurice for help, and the latter not only assisted him but even called Chosroes his son; Roman and Persian forces fought together against the usurper.14 As a result, Chosroes ceded to Rome not only Martyropolis and Dara but also parts of Armenia and Iberia (Georgia), and an unusual peace prevailed between the two empires for more than ten years.

The Byzantines and the Sasanians both ruled over vast areas with highly disparate populations and had much in common in terms of kingship and organization.15 Christians, for example, constituted a substantial element in the Persian empire, and were embedded in the royal court.16 Tensions persisted with the Zoroastrian establishment, but by the end of the sixth century the religious ferment in the Near East as a whole was felt at the highest level. Imperial policy was also dictated by realism. What might seem a strange decision on the part of Maurice, to support his natural enemy rather than to profit from the internal discord in the Sasanian kingdom, as some urged, was both a demonstration of solidarity between kings and a hardheaded recognition of reality; neither side could or would aim at the total defeat of the other. Each side knew the strengths and weaknesses of the other from centuries of experience, and Maurice himself is credited with the Strategikon, a military manual discussing all aspects of late Roman warfare including the military characteristics of the Persians.17

Map 9.1 The east in the early seventh century

This situation was soon to change. In 602 Maurice was deposed by Phocas, an army officer proclaimed by disaffected and ill-supplied troops in the Balkans. With Phocas outside Constantinople, the emperor called in the aid of the factions, but the Greens opted for Phocas, and Maurice was put to death with all his family.18 For the last two decades the empire had also had to contend with assaults from the Avars and Slavs in the Balkans, and it was in this context that the soldiers raised Phocas as emperor. Chosroes took the opportunity to launch a major campaign against Byzantium on the pretext of avenging his adoptive father, parading Maurice’s alleged surviving son Theodosius. Dara, only recently recovered by the Romans, was besieged and fell in 604 and this was followed by the capture of all the cities east of the Euphrates, Edessa, Harran, Callinicum and Circesium. The Persians were assisted from 609–10 by widespread disturbances in the Roman east involving the factions,19 and the position of Phocas became more and more vulnerable. In this situation, Heraclius, the exarch of Africa, launched an expedition by sea which took Alexandria, the key port for the dispatch of the grain supply to the capital, and established itself on Cyprus; his son, also called Heraclius, was able to sail to Constantinople where he was welcomed, not least by the Green faction. In October 610 Heraclius became emperor, and Phocas was killed.

The Persian advance continued and Caesarea in Cappadocia was taken after a long siege; despite a Roman advance into Syria, the Persians moved south, taking Damascus and then Jerusalem in 614.20 The patriarch and many of his people were taken with the True Cross to Ctesiphon, and according to Christian sources, the Persians sacked the city with great slaughter and de-ported many of its inhabitants. The fall of Jerusalem was followed by that of Alexandria (617), and Persian armies also stormed through Asia Minor, sacking Ephesus and Sardis and reaching Chalcedon. Palestine, Syria, Mesopotamia, Egypt and much of Asia Minor were under Persian control by 622, and the situation looked desperate for Constantinople, with attacks by the Avars and Slavs in the Balkans, an Avar siege of Thessalonica in 618 and the serious blow caused by the loss of the grain supply from Egypt.

The Persian Conquest of Jerusalem

The Persian advance and capture of Jerusalem provoked a bitter backlash against the Jews among Palestinian Christians, who blamed them for aiding the invaders. Christian sources, including the early-ninth century chronicle of Theophanes, important for this period, and the contemporary account attributed to Strategius, a monk of St Sabas, and surviving in Georgian and Arabic versions of the original Greek, the Life of George of Choziba, one of the Judaean desert monasteries, written soon after the events, and the narrative of the Armenian ps. Sebeos, are just some of the sources displaying a strong hostility to Jews.21 Much of this anti-Jewish expression belongs to a long rhetorical tradition among Christian writers in late antiquity, but there is some reason to think that Jews in Palestine were courted at first by the Persian invaders and even briefly entertained hopes of recovering the Temple Mount. Strategius’ claim that Christians perished after being crammed by Jews into the Mamilla cistern in Jerusalem has been connected, plausibly or not, with physical evidence for burials.22 Jewish apocalyptic flourished in this atmosphere, as did the recent genre of Hebrew liturgical poetry known as piyyutim (Chapter 8). Religious differences came to a head with the prospect of a change in the control of Jerusalem,23 and in 632, after the restoration of the True Cross to Jerusalem, Heraclius decreed that all Jews must convert, a measure which came to little if anything, given its date, but which indicated and encouraged Christian anti-Jewish feeling. The genre of Christian apologetic dialogues between Christians and Jews, reviewing and refuting standard Jewish arguments against Christianity and invariably leading to the triumph of the Christian debaters, also flourished in the seventh and eighth centuries. In the anonymous Quaestiones ad Antiochum ducem, perhaps of the early eighth century, Christians are given arguments to use against Jews, or to reassure themselves, on topics such as the direction of prayer, circumcision, the veneration of created objects, the status of Christ, the destruction of the Jewish Temple and the superiority of Christianity.24 A particularly striking, though not typical because less formulaic, example of the anti-Jewish dialogues is the so-called Doctrina Jacobi nuper baptizati of the 630s, telling of a converted Jew, which unusually contains much apparently circumstantial detail about Jewish communities in the eastern Mediterranean and Jacob’s own involvement in factional disturbances.25 A vivid impression of factional violence in various cities in the last days of Phocas is given by the Egyptian chronicler John of Nikiu (for whose work we depend on an extremely late Ethiopic translation from a lost Arabic paraphrase of the probably Coptic original), and while this is a difficult source on which to rely, many others confirm this picture of urban disturbances all round the Mediterranean, in which the factions joined in or sometimes took the lead (Chapter 7 above). Inscriptions at Ephesus, Oxyrhynchus and Alexandria confirm their importance and their bestowal of political support, and Phocas seems to have alienated the powerful Greens. The Doctrina also reflects this tense atmosphere when recounting the exploits of Jacob in his youth, before his conversion:

[In the reign of Phocas], when the Greens, at the command of Kroukis, burned the Mese [in Constantinople] and had a bad time [cf. Chron. Pasch., 695–6], I roughed up the Christians and fought them as incendiaries and Manichaeans. And when Bonosus at Antioch punished the Greens and slaughtered them [609], I went to Antioch … and, being a Blue and on the emperor’s side, I beat up the Christians as Greens and called them traitors.

(Doctrina Jacobi I.40)

The fall of Jerusalem and the capture of the empire’s most precious relic, the True Cross, were matters of deep mourning for Christians and, as we saw, Sophronius, later patriarch of Jerusalem himself, composed poetic lamentations in the classical metre of anacreontics.26 The joy when the Emperor Heraclius returned the Cross to Jerusalem in 630 was correspondingly great, and Sophronius and others did not fail to rejoice in what they saw as the discomfiture of the Jews.27 But the Cross had been received in Ctesiphon with joy and celebration, not simply as a trophy of victory but also as a Christian symbol.

Persian Occupation and Roman Recovery

Internal arrangements during the period of Persian occupation are hardly known, but papyrological evidence from Egypt suggests that little was changed and that the new rulers left existing administrative structures in place.28 For the continued warfare we have detailed accounts in the Chronicon Paschale, the early ninth-century Chronicle of Theophanes (which draws on earlier sources), the poems of George of Pisidia and the Armenian writers ps. Sebeos and Movses Daskhurani, all of which have been covered in recent studies.29 Peace having been made with the Avars in 620, Heraclius turned to gathering an army large enough to take on the Persians, melting down church treasures and a bronze ox that stood in the Forum Bovis in Constantinople. Despite winning a victory in battle, he soon had to return to confront the Avars, and agree to pay them a large annual subsidy before setting off again for Persarmenia. He dared to stay away from the capital during the dangerous Avar–Persian siege of 626, though he may have returned that winter. He had formed an alliance with the Turks and with them entered Persian territory; disaffected Persian nobles put Chosroes’ son Cavadh on the throne and Chosroes was executed. Cavadh entered negotiations with Heraclius, and the latter announced his extraordinary success in a letter read out in St Sophia in May, 628.30 Diplomatic conventions were maintained, and the new Persian shah addressed Heraclius as ‘the most clement Roman emperor, our brother’. Peace was made in 629, with the Euphrates as the agreed border. The Sasanian kingdom lasted for two more decades, until 652, with the death of Yazdgerd III after a period of internal rivalry and confusion; the Persians continued to put up a resistance, but it was the Arabs, not the Romans, who defeated them. But the centuries-old threat which Persia had posed to Rome was over, and in 630 Heraclius triumphantly restored the True Cross to Jerusalem. The emperor’s emotion is described by ps. Sebeos:

[There was] the sound of weeping and wailing; their tears flowed from the awesome emotion of their hearts and from the rending of the entrails of the king, the princes, all his troops and the inhabitants of the city. No-one was able to sing the Lord’s chants from the fearful and agonizing emotion of the king and the whole multitude.

(Ps.Sebeos, 41, Thomson and Howard-Johnston, I, 90; II, 24)

Even if the Roman empire was better able to sustain the effort to defeat the Persians than many historians have assumed, the effects on the Roman economy as a whole of this prolonged warfare, alternating with periods of annual heavy payments, must have been very great, and the operational requirements in the east were also expensive and complex.31 Meanwhile the Avars and Slavs were able to overrun western Illyricum and Greece and mount serious raids on Thessalonica; the city’s survival was attributed to the intervention of St Demetrius in the Miracles of St Demetrius.32 The Persian wars have been given a major role in the acute downturn in the fortunes of old classical cities, especially in Asia Minor, 33 but as we saw, recent archaeological work on Syria and Palestine suggests that the material impact of the Persian invasions there was limited (Chapter 7). There is, however, evidence that they provoked flight in some sectors of the population in the wanderings of Sophronius and Maximus Confessor, who settled in North Africa, the influx of monks and clergy from the east in Sicily and south Italy, the impact of which is still evident today in the churches and villages, and the case of St John the Almsgiver, who fled from Egypt to Cyprus, justifying his action in Scriptural terms. It may be dangerous to draw general conclusions from limited evidence, and warfare and conquest were not the only factors causing urban downturn, but the combined effects of the successful Persian and then Arab invasions caused disruption in particular places, brought negative economic consequences, ended the grain supply to the capital and detached large areas of territory and the tax base from the control of Constantinople.

The Arab Conquests and the Coming of Islam

Scarcely had Heraclius returned to Constantinople after his entry into Jerusalem than another, and this time unforeseen, threat emerged in the east. Also in 630, Muhammad and his followers returned to Mecca from Medina, and Muhammad’s leadership was established in Arabia. Muhammad himself died in 632, but Muslim raids into Palestine had begun by 634. It would seem in fact that a major advance was already taking place further south while Heraclius was occupied with the celebration of his victory over the Persians. Despite a defeat at Mu’ta in 629, largely at the hands of other Arab tribes, an Arab army took Tabuk in the northern Hejaz, whereupon three important Byzantine centres in eastern Palestina Tertia – Udruh and Aila (Aqaba), both legionary fortresses, as well as Jarba – simply surrendered, giving the Muslims access to southern Palestine. Again, the chronology of these events is hard to establish, but when the Muslims did reach the Negev and Gaza it seems clear that these areas were undefended, and they met relatively little resistance. Whatever the reasons, the infrastructure of defence which might have stopped the Muslims as they moved from Arabia into Palestine and Syria was absent.

The Arab advance was spectacular. Three battles took place between 634 and 637 at Ajnadayn, between Jerusalem and Gaza, Fihl (Pella), and the river Yarmuk. Damascus fell after a long siege, and according to tradition Jerusalem was dramatically handed over, according to Arabic sources, to the Caliph ‘Umar I, walking on foot and dressed in dirty clothes to show his humility, by the patriarch Sophronius in 638; later tradition records the ‘Covenant of Umar’ with the people of Jerusalem. Alexandria fell in 642. The unfortunate Heraclius saw his armies defeated at the Yarmuk; bidding a famous farewell to Syria, as reported in later Syriac chronicles, he returned to Constantinople, where he died in 641. Alexandria was taken in the next year and the Arabs raided Cappadocia; they soon made damaging attacks on Cyprus and won a spectacular naval battle in the bay of Phoenix off the coast of Lycia in southern Asia Minor. They even reached the Bosphorus and threatened Constantinople, though this time they were forced to retreat. A few contemporaries recognized the importance of Muhammad, whom they regarded as a false prophet. In the 630s the Doctrina Jacobi cites a contemporary letter, supposedly from a Palestinian Jew called Abraham, according to whom a false prophet had appeared among the Saracens, foretelling the coming of the anointed one. Abraham asked a wise old man, expert in the Scriptures, about this, and the old man replied

‘He is an imposter. Do the prophets come with swords and chariot? Truly these happenings today are the works of disorder.’

Abraham then made enquiries himself and was told that the prophet claimed to have the keys of paradise, which Abraham regarded as completely incredible and therefore as confirming the old man’s words.34 But at first the Byzantines were slow to realize that the invaders were other than ‘Saracen’ raiders with whom they had been familiar since the fourth century, and Christian sources emphasize their ‘barbarian’ ferocity. It is in general only later that Byzantine writers begin to show awareness of the religious content of Muhammad’s teaching. The account given by the chronicler Theophanes (d. 817), based on an earlier eastern source, mixes hostility and slander with genuine observation:

He taught his subjects that he who kills an enemy or is killed by an enemy goes to Paradise; and he said that this paradise was one of carnal eating and drinking and intercourse with women, and had a river of wine, honey and milk, and that the women were not like the ones down here, but different ones, and that the intercourse was long-lasting and the pleasure continuous; and other things full of profligacy and stupidity; also that men should feel sympathy for one another and help those who are wronged.

(Theoph., Chron., 334, Mango and Scott, 465)

Thus there was as yet little understanding, and there is a strong emphasis on the sufferings of the local populations in the written sources, especially those in Syriac. At the same time archaeological and other evidence suggests that the ‘conquests’ themselves did not at first represent a major break in continuity in the eastern Mediterranean provinces, especially as the Islamic rulers at first simply took over the main framework of the Byzantine administration and continued to use Greek-speaking officials to run it. The real change was to come only later, from the late seventh century onwards, and especially with the end of the Umayyad dynasty and transfer of government east to Baghdad in the mid-eighth century.

The course of the early conquests and the reasons behind them have been endlessly debated, and it has long been recognized that for contemporary sources we have to look to non-Islamic material; historical writing in Arabic took time to develop, and when it did it was based on oral material, including the sira (biographies of the Prophet), the hadith (acts and sayings of the Prophet) and isnads (reported ‘chains’ of witnesses), the nature of which is also controversial. Traditionalist modern accounts, and Muslim tradition itself, are based on a broad acceptance of this evidence, while revisionist approaches are strongly sceptical.35 A more moderate position seems to be emerging, based on very detailed analysis of the Arabic writers, and giving weight to their presentation of pre-Islamic Arab culture, especially through the pre-Islamic Arabic poetry they preserve. Analysis of the events of the conquests themselves is coloured by these different approaches, with some arguing for a centrally controlled and determined programme of conquests driven by religious motives and others for more inchoate beginnings, with the systematic development of Islam itself seen as crystallizing only in the Syrian context. From the perspective of the Christian and Jewish populations of the Near East, and of the Byzantines in Constantinople, who were naturally preoccupied with the experience of defeat, it is not surprising if it took time to understand the phenomenon of emerging Islam. It seems unlikely that the anti-Jewish dialogues of the later seventh and eighth centuries were in fact veiled attacks on Islam, as has sometimes been argued. Rather, there seems to have been little actual awareness of the Qur’anic message before the later seventh century, and John of Damascus’ eighth-century chapter on Islam (which he saw as a Christian heresy) is the first discussion in any detail; even then the passage is simply an extra chapter tacked on to the end of his listing of one hundred heresies.36 Apocalyptic literature circulated in Greek and Syriac towards the end of the seventh century, but this was most concerned to place the defeat of the Roman empire within an eschatological frame.

A turning point came during the caliphate of Abd al-Malik (685–705) when a more aggressive line was adopted towards Christians, the Dome of the Rock was built on the site of the Jewish Temple (below) and a new non-figurative coinage was adopted. In 707 the great cathedral in Damascus, itself built over a Roman temple, and which had hitherto been used for prayer by both Christians and Muslims, was transformed into the Great Mosque that we see today.

By about 700, after decades of warfare, and certainly by 718, when the Arabs were already in Spain and a dangerous Arab siege of Constantinople was narrowly resisted, it was clear that the new rulers of the east were there to stay.

Figure 9.1 The Great Mosque at Damascus (early eighth century), built on the site of a Christian church and Roman temple

Christian Religious Divisions and Religious Reactions

The ordinations of Miaphysite clergy under Justinian had had the effect of creating a divided church and of giving the Miaphysites an established position. But as we have seen already, the east was not uniformly Miaphysite, even in strongly Miaphysite areas; the patriarchate of Antioch, for instance, passed several times between Chalcedonian and Miaphysite control, and there were both Miaphysite and orthodox communities in Edessa when Heraclius was there during his campaign. It has often been supposed, nevertheless, that the religious divisions among Christians aided the Arab conquests by reducing loyalty to Constantinople among the anti-Chalcedonians, and diverting attention from the need for defence, a theory for which there is little direct evidence.37 If cities surrendered without fighting, it was because they had little choice, not because they preferred the Arabs to the Byzantines; they had faced very similar choices before – for instance, during the Persian wars of Chosroes I under Justinian – and behaved in similar ways when the alternative would have been a disastrous siege or violent capture. There was no shortage of military response in any case, and this was not in the hands of local clergy or local communities. It may be true that the Arab armies were motivated by a religious theory of the rewards of jihad, but Heraclius’ wars were also seen by contemporaries as religious wars, and troops were spurred on by the use of Christian relics and images. The early Muslims were deeply divided themselves; the beginnings of Muslim rule outside Arabia were marked first by the ridda wars, or ‘wars of apostasy’ against the rule of Abu Bakr after Muhammad’s death, then the murder of the Caliph ‘Uthman in 656 and the coming to power of Mu‘awiya in the context of the assassination of Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law ‘Ali; this was followed by the death of the latter’s son, Muhammad’s grandson, Husayn, at Karbala in 680.38 The murder of ‘Uthman in particular (656) gave the Byzantines a breathing space and the chance to reorganize, but Heraclius had already begun the process of changing the army structure, and there was also work on the refortification of key coastal cities in Asia Minor.39

It is naturally tempting to imagine that after decades of warfare the Byzantines were in no condition to take on another enemy, but less easy to assess the actual military strength of the empire in the east; to the arguments that there had been a progressive reduction in defence and that Heraclius’s campaign against the Persians in the 620s was only possible because of desperate recruiting measures, it may be responded that Byzantium was still capable of gathering and dispatching considerable forces both before and after the Arab conquests.40 The contest was not all one-sided and the Muslims suffered several serious reverses. The late seventh and early eighth centuries were very difficult for the eastern empire, and there is also a gap in the coverage of the historical sources for about twenty years in the mid-seventh century, so that much detail remains obscure; one can imagine, however, that a serious lessening of the availability of elite education followed the loss of territory and the damage to cities. The state had lost a huge part of its tax-base and in the capital the Aqueduct of Valens which was essential for the city’s water supply was not repaired after being damaged during the 626 siege, with a consequent dramatic downward impact on the population. The Emperor Constans II (641–68) moved his court to Sicily and was eventually assassinated. The Mediterranean became unsafe and open to the development of Arab piracy. But above all, Constantinople was not taken. The Byzantine state was much reduced and had to change its administrative, financial and military structures as a consequence. But its core institutions were able to adapt and survive.41

This was so despite the strength of the opposition, especially from the eastern provinces, to the efforts of Heraclius earlier in the century to find a solution to the christological divisions which still separated the church (Chapter 8). Miaphysites were not the only anti-Chalcedonians; the so-called ‘Nestorians’ also maintained that Christ had only one nature (the human), and the decisions of the Council of 553 had met with hostility in Italy. The successors of Justinian did not give up on their efforts to manage the situation, which was seen not only as politically dangerous but also as likely to bring divine punishment on the empire. The first formula was promoted by Heraclius in 633, soon after his success in restoring the Cross to Jerusalem, but Monoenergism, the theory that Christ had one ‘energy’, provoked opposition from Chalcedonians, and in 638 an imperial statement, the Ekthesis, displayed in St Sophia, proclaimed Monotheletism, the theory that Christ had a single will.42 In the same year Sophronius, as patriarch of Jerusalem, surrendered the holy city to the Muslims, but he had already been a leader in orchestrating local meetings of bishops to oppose the innovation, and formally condemned the imperial religious policy.43 Sophronius died, also in 638, and the opposition was continued by Maximus Confessor from his monastery in Carthage; in 645 Maximus publicly debated in Carthage with the former patriarch and Monothelete, Pyrrhus, and then left for Rome to organize the campaign from there (Chapter 8). The seventh-century popes were equally opposed to the imperial innovation, and both Pope Martin I and Maximus were arrested and taken to Constantinople for trial. Yet Monotheletism did not prevail. It was formally rejected by the Sixth Ecumenical Council held in Constantinople by the Emperor Constantine IV in 680–1. Not only was Maximus’ reputation vindicated, but his theological writings established him as one of the most important of all Orthodox theologians.44

The seventh century was a period of intense and profound theological discussion, of which the central theme remained that of the nature of Christ. What did it mean that man was made in the image of Christ? How could the human and the divine natures of Christ be known? Did God suffer in the flesh in the crucifixion? Concerns had already been raised in the late sixth century about the cult of saints and their efficacy to intervene after death (Chapter 3), and a growing anxiety about religious images and especially depictions of Christ, and about the status of visual images as conveyors of truth, revealed itself in seventh-century writing, including the works of the monk Anastasius of Sinai and the anti-Jewish disputations. This debate and anxiety was part of the context for a prolonged argument in the next century about the status of images as compared with writing.45 Sets of questions and answers on theological topics also survive from this period and are indicative of the need to explain issues of faith and practice in a situation that must often have seemed bewildering. It was in this crucial period that Maximus Confessor and after him Germanos, patriarch of Constantinople, 715–30, set out the symbolic understanding of the church and the liturgy that was to underpin eastern Orthodox thinking thereafter. As well as condemning Monotheletism, the Sixth Ecumenical Council in 681 recognized the degree of passion that had been aroused, and the likelihood of manipulation or falsification of evidence; the same concern was to persist in connection with the councils of the eighth century. Neither the fifth nor the sixth council had issued moral or pastoral canons and in 691 a further council was held in order to fill this gap, known as the Council in Trullo after the room in the palace where it met, or the ‘Quinisext’, after its status as an appendix to both the fifth and the sixth. Deep doctrinal divisions and the disturbance of church order that came with them also had profound ethical implications and church discipline needed to be reasserted. The intellectual and religious history of the period went together with its political and military history, and was frequently interwoven with it; it cannot be separated in modern accounts.

Christians under Islam

At first little seemed to change in the provinces that were now part of the Umayyad caliphate. The rulers concentrated on military aims and on their Arab and other Muslim followers, who received preferential treatment in the form of financial annuities, provision for their religious needs and settlement in new foundations. These included al-Kufa, very near to the Lakhmid centre at Hira, al-Basra and Wasit, all in Iraq, Fustat in Egypt and Kairouan in North Africa. Palestine and Syria were already highly urbanized and there and in north Mesopotamia such settlements were few; as under the Persians, the existing administration was largely left to run everything. But during the rule of Abd al-Malik (685–705), in the late seventh century a more forceful policy was adopted for the control of the Christian population and the assertion of Islam. The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem built by Abd al-Malik carries anti-Christian verses round the inside of the dome,46 and Christians were forbidden to parade the cross, figural motifs were removed from the coinage and Arabic replaced Greek as the language of administration. The change was clear. Some Christians longed for a restoration of idealized Roman rule, but in many ways community life continued as before. This included the intellectual activity of Christian writers in Syriac, who translated Greek texts and wrote on theology, mathematics and philosophy, in a tradition which was to continue for centuries. Jacob of Edessa (d. 708) was a prolific author who had been born in the territory of Antioch in about 633 and entered the monastery of Qenneshrin, travelled to Alexandria, became bishop of Edessa, but then spent his life in monasteries including Tell ‘Adda, returning to Edessa for only a few months just before his death. Jacob produced works on grammar, history, exegesis, philosophy, liturgy, and collections of rules (‘canons’) and rulings on matters to do with Christian life under the Muslims, some in the form of answers to questions posed by others.47 Just as earlier collections of questions and answers had dealt with the problems posed by intersectarian divisions among Christians such as the validity of the Eucharist if the elements had been consecrated by a ‘heretic’, so Jacob gave guidance to Christians about their necessary relations with Muslims in daily life. Thus a monk or deacon could participate in battle in the Muslim army if forced, but must not kill; priests may bless a Muslim; Christians may attend funerals of pagans and Jews.

Such were the day-to-day issues that faced all Christian communities, not only the Syrian Orthodox. In Egypt there is abundant papyrological evidence in Greek and Coptic for continuing Christian life in the early Islamic period.48 In Palestine, the dyophysites who remained in communion with Chalcedonian orthodoxy were later known as ‘Melkites’, meaning those who supported the emperor, or the ‘king’. Their centre remained the patriarchate of Jerusalem and the Palestinian monasteries, though they were certainly not confined to these areas, and John of Damascus and his disciple Theodore Abu Qurrah, bishop of Harran, who wrote in Arabic, were key theologians in the eighth and ninth centuries. In the major centres and in the higher echelons of the clergy, Greek continued in use among the Melkites, but by the ninth century the Palestinian monasteries were multilingual, and the wider Christian population in Palestine moved as easily from Aramaic to Arabic as monastic and ecclesiastical writers did from Greek.49 The Church of the East, or Assyrian Christians, often wrongly labeled as Nestorians, stressed the human rather than the divine nature of Christ.50 All these groups have survived until the present day.

In the sixth and seventh centuries the numerous monasteries of the Judaean desert were important centres, ranging from small hermitages to very large coenobia such as the monastery of Martyrius. Some remained in use until the nineteenth century, and St Sabas, east of Bethlehem, continues even today, though it has been extensively rebuilt and lost much of its monastic library to collectors in the nineteenth century. St Catherine’s monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai is in a more isolated position and was able to maintain itself without interruption throughout the various vicissitudes of succeeding centuries. It still displays a letter supposedly from Muhammad, guaranteeing the freedom and protection of the monastery. St Catherine’s also houses extraordinary collections of manuscripts and icons, and many more manuscripts were discovered in the course of restoration work in 1975. St Sabas is very differently positioned, not far from Bethlehem and within close reach of Jerusalem. In the eighth and ninth centuries it was a centre of learning and attracted monks with a wide variety of backgrounds and languages. By the ninth century Arabic was displacing Greek, but like St Catherine’s, St Sabas remained in modern terms Greek Orthodox, i.e. Melkite. John of Damascus was almost certainly a monk at St Sabas, though the direct evidence for this is in fact rather slight, and St Sabas became a powerhouse for religious debates even in Constantinople in the eighth and ninth centuries.51 Monasteries in Mesopotamia and the Tur Abdin also remained centres of learning for many centuries, and of these also some continue today.

The general condition of Christians and Jews under Islam has been much debated. As Peoples of the Book they were technically protected, but occupied a lesser status as non-Muslims and were subjected to various constraints including the poll-tax (jizya).52 Christians naturally tended to produce stories of ill-treatment and even some accounts of martyrdoms at the hands of the Muslim authorities, whether of individuals or groups, such as the tale of the sixty martyrs of Gaza, soldiers imprisoned while defending the city of Gaza in 637, who subsequently refused to convert to Islam; but such cases were few in number, and the accounts are ideologically driven.53 At the same time Christian communities in the Umayyad period were still engaging in church building and restoration, to the extent that the paradoxical term ‘Umayyad churches’ has been coined for the new or remodelled churches of this period. Robert Schick has produced long and impressive lists of churches that remained in use and churches that were newly built or restored in the period 640–813, as well as a corpus of sites, and some of the most spectacular and interesting of the mosaics already mentioned date from this period (Chapter 7).54 The built landscape changed slowly. Church building work, as at Palmyra in Syria or at Umm er-Rasas in Jordan, coexisted with the so-called desert palaces and bath-houses (qusur) at Qasr al Hayr al-Gharbi, Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi, Hallabat or Qusayr ‘Amra and elsewhere. The frescoes of Qusayr ‘Amra in particular, in modern Jordan, with their depictions of six kings, four of them labelled in Greek and Arabic as rulers in the late antique Mediterranean world (Caesar, Roderic, Chosroes and the Negus), and combined with mythological and other scenes, are an extraordinary testimony to the breadth of cultural and artistic connections among the Umayyad elite.55 It is not surprising to find a strong Sasanian artistic influence in these structures alongside the East Roman borrowings, whether in iconography or in the use of large-scale stucco decoration. Nor is it surprising that they were built in or at the edge of the ‘desert’, away from but within reach of the major urban centres; on one level they were retreats and country residences for their patrons, but they also tended to be located on main routes and on sites which facilitated communication with and control of the local tribes, and some had gardens or water installations. It is also possible to trace continuity of village settlement between the Roman and Umayyad periods in Transjordan and elsewhere.

The unevenness of available archaeological evidence means that it is harder to assess the impact of Umayyad rule on the major cities, though with some notable exceptions, especially Jerusalem and Amman, and at well-excavated sites such as Jerash, Pella and Umm Qays, and Muslims remained a small minority in the population as a whole. But it is clear that mosques, administrative and commercial structures were built in main and secondary centres including Jerusalem, Amman, Resafa, Tiberias, Jerash and Scythopolis.56

Figure 9.2 Nessana in the early 1990s. An important cache of sixth–seventh-century papyri in Greek, Latin, Syriac and Arabic was found here in 1935 during the excavation of one of the churches.

Change and Continuity in the East

It is certainly true that the emphasis on late antique continuity into the Islamic period in recent scholarship, with the ‘break’ usually seen as coinciding with the end of the Umayyads and removal of the capital to Baghdad in the eighth century, depends heavily on a concentration by late antique scholars on the eastern Mediterranean. Here too, however, deep changes came as a result of the Arab conquests, even if the conquests themselves left less trace on the archaeological record than previously assumed. The conquests also brought very serious consequences for the Byzantine state, and while Constantinople managed to escape being taken by the Avars and Persians and by the Arabs, it was dramatically diminished as a city by the eighth century. Even before that, the late seventh-century government went through very difficult times. Neither cultural nor economic explanations are in themselves sufficient to explain the changes that were taking place in the period; we must also bring in political and military factors, even while recognizing that the sixth to eighth centuries were a time of intense intellectual and religious ferment. I have earlier referred to this process as a ‘redefinition of knowledge’,57 and indeed such was the acknowledged or unacknowledged goal of many Christian contemporaries. However, it is worth remembering that the need for such a redefinition arose from a situation of change, conflict and uncertainty in all parts of the Mediterranean world. Reactions were very diverse. One recent contribution refers to the sixth and seventh centuries as having ‘witnessed the most protracted, detailed and fiercely contested debate on personhood and anthropology in human history – certainly in the history of the ancient world – as Christian, Jewish and ultimately Muslim monotheisms fought to define the various “orthodox” versions of their beliefs about God, man and the universe.’58 The only way that the general history of this extraordinarily crucial period can truly be approached – including the issue of the ‘end of antiquity’ – is by rejecting an insistence on one factor over the others (economic over cultural history, for instance) and attempting instead to bring these different approaches together. That said, while this chapter has indeed been largely about the east, the Conclusion will address some of the wider (and contested) issues about the Mediterranean world in late antiquity.