WORDS OF WISDOM

Authors’ note: As discussed in the preface, we originally started writing a story about reading the wind for Precision Shooting magazine. We started with a simple idea ... how do you think about reading the wind? We came up with a simple thought process that we feel is pretty effective. But then we wanted to add some techniques and tactics, and then, because we believe that these things are all completely “learnable,” we had to put in something about the underlying skills.

Somewhere, in the midst of all that, the entire story became completely unmanageable. Keith suggested that we stop struggling and just treat it like a short book instead of a long story. So we did. We added a chapter on basics. Then we thought about what else we wish we had known before we had started competitive shooting at long range and decided to add a chapter of “words of wisdom,” wind-reading thoughts from some of our best long-range shooters.

We decided to gather this information from any excellent wind readers and started by canvassing the members of the Dominion of Canada Rifle Association (DCRA) Hall of Fame, as well as top shooters from the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, South Africa, and elsewhere. Some of these top shooters were recommended by their national rifle associations, while others were recommended by PALMA Team coaches, and still other individuals we contacted directly. We explained our situation to them and asked them specifically for their help:

“It’s in the last chapter, ‘Words of Wisdom” that we need your help. What we’d like to include is your thought process . . . what do you think about when you are reading the wind? What do you wish you had known about ‘wind thinking’ before you started competitive shooting at long range?

“We’re looking for a few paragraphs (or so) on your thought process and perhaps a short example of a time it really contributed to a successful performance.”

The rest of this chapter is the result of what we received from these esteemed shooters, and their advice is told in their own words. That is, while the other chapters in this book are told from our perspective, the remainder of this chapter is written from the perspective of the guest authors who contributed these words of wisdom. We are forever indebted to the shooters who shared their thoughts with all of us. It was certainly not easy for all of them to put their thoughts down, and we are touched by their efforts on our behalf. As George Chase said, “What you are about to receive from shooters around the world should make for an interesting read.” Indeed.

EDUARDO ABRIL DE FONTCUBERTA, SPAIN KING OF 2 MILES

Dealing with Wind at Extreme Long-Range Shooting

Shooting past one mile1 is what the Extreme Long Range (ELR) community has recently agreed as true ELR. There was a lot of argument about the real challenges involved and how to set a threshold that we could call “ELR.” Most of the ELR leaders agree that once a certain caliber goes into the transonic zone, a new set of external ballistics unknowns come into play, be it 700 yards for a 30-30, or 3000 yards for a .375 CheyTac.

For most modern shooters, obtaining an accurate fire solution at 1000 yards is not a problem, thanks to the latest developments in ballistics software and measuring equipment. Distance to the target, meteorological conditions (MET), and environmental conditions (ENV) such as shooting angle, are not unknowns anymore.

There seems to be a new sense of confidence that comes from how easy is to obtain a good fire solution using these new tools. The problem is that once this over-confident fire solution hits a certain range, high hit ratios drop radically, and misses become the norm.

If you are reading this book, then you are motivated enough to face the challenges of shooting past one mile and to try to understand what is involved in increasing that hit ratio to an acceptable point. Don’t believe those false Gurus out there on YouTube making claims of a cold bore 4000-yard shot. We are not yet ready for that; just check the King of 2 Miles (Ko2M) scores.

To achieve those ELR hits we first need to better understand the little-known factors that are affecting our bullet’s point of impact. Some of these factors come from the internal ballistics like bore compression, from the external ballistics like aerodynamic jump or hyper stable flight, or from our environment (like the wind).

What We Know

Right now, we have a good set of measuring equipment available that remove from the unknowns some of the critical factors that affect our shooting. We now measure muzzle velocity (MV) with ease with Magnetospeed magnetic chronographs and LabRadars, or use the huge BC (ballistic coefficient) libraries available from manufacturers, which are more accurate that most might want to admit.

We even have custom drag curves from several ballistic solution manufacturers such as Hornady, Lapua and Bryan Litz (Applied Ballistics) that allow us a high impact ratio with little effort, but only for some bullets they have custom profiled.

Kestrel has brought full meteorological station capabilities to the shooters and Vectronix’s laser range finders are widespread at ELR firing lines.

We have new hardware such as TACOM HQ Charlie optics, Ivey adjustable mounts, superb new riflescopes designed for ELR such as Schmidt und Bender 5-45x56 and also new calibers, new barrel twists and new bullets. So, are we ready for pushing the envelope?

What We Don’t Know

This is when the story gets interesting. With the above knowns and hardware, we have enough data to work reliably up to 1000 or 1200 yards with a very high hit ratio. If we use the latest hardware we can increase that a little more, but as soon as we get close to a mile and require cold bore shots, or repeated hits, the misses will start to add up. Why?

Just check the World Record attempt at the 2018 Shot Show and you will find that some of the best shooters in the World struggled to get past one mile if required to hit 3 out of 3 on a cold bore. And think about the superb work by Nate Stalter from David Tubb’s team that came in with the record with 2011 yards, and check the equipment they had, as this configuration, with a Magnetospeed permanently installed and an advanced thermal camera so the spotter could see the bullet trace, tells you a lot about what we are facing.

You would have expected more, wouldn’t you? This is our reality check.

In my humble opinion, we are struggling at 2000 yards when required to hit cold bore because we still need more refinement in our software solutions and because of the great unknown: the wind.

Ballistics software is a key component of our ELR arsenal, if not the single one most important and critical. Without software, it’s virtually impossible to succeed in ELR , so try to master it early on.

In this day and age there are a good number of offerings on the market ranging from “good enough” to very sophisticated software applications. Those of us who have been dealing with the “reach out and touch something” for long enough were among the first ones to embrace this evolving technology with passion. And for a good reason as software alone changed long range shooting in many ways.

But we are talking about WIND here, the elusive variable that to tackle down requires a good dose of art. Even today, the so-called wind-doping, is considered by many to be some sort of obscure art, and for a good reason.

At this point, I guess is important to realize that Wind is always affecting the bullet’s drag, the critical aerodynamic parameter that defines how well the bullet “cuts the air.” Sometimes, we used to think that headwinds or tailwinds should not to be taken into account. This is a false notion and in the ELR world, this can put you down easily. The bottom line is that Wind affects drag from any direction.

Wind is responsible not only for Windage but also for “Aero Dynamic Jump,” a vertical deflection caused by the crosswind component of the surface wind. Therefore, these two main factors call for the best ballistics software to appropriately deal with them.

Since wind is rarely blowing constantly from the same direction and speed, the top ballistics programs offers the capability to work with “multiple wind zones.” This feature allows the user to “bracket” the wind into several zones entering wind direction and speed for a certain yardage. I’m not saying this is easy to do, but the experienced wind masters know a trick or two to fill in the right data and get the most out the final fire solution.

The best software packages are less than a fistful, and standing up among them is ColdBore from Patagonia Ballistics. A very accurate and robust program based on a proprietary ballistics engine that has proven itself in the game of ELR for over a decade. It’s very interesting to see how ColdBore deals with wind; undoubtedly the proprietary engine is calculating the windage differently than the rest, the usual “Point Mass” solvers that make up 99 percent of the market. Some of the most accomplished shooters have reported that Point Mass-based programs fail their windage predictions with a tendency to increase the necessary windage, while ColdBore is right on the money.

But, just as most software solutions out there are lacking, in regards to crosswind component wind corrections, so is our capability to measure or estimate a wind speed number to plug in.

We need to reconsider some aspects of our shooting that many shooters might consider under control when they first buy a new Kestrel, and that are not really under control. The most obvious and the object of this article is the true wind.

The True Winds

Wind is not a constant, it is a dynamic force. It is not constant in direction or speed and changes both as it moves along the surface of the earth (being channeled through creeks towards flat lands) and being heated by the ground and the sun. To make matters worse the wind can be totally different in different sections of our bullet flight, due to the topography of the zone, the height at which the bullet is flying, and also the chaotic nature of our earth’s clouds, sun and winds. Our nature.

I see many shooters with their hand up high, holding their Kestrel to get “a number” a wind speed, something to work with as a starting point. And this is one more proof about how little shooters, as a group, know about the wind.

The only way to get an accurate wind deviation on our bullet is from the point of impact feedback. This is one of the few real data we will ever have, but in many environments is difficult to see, and is perishable in time. The wind we see affecting our bullet now may not even be there anymore in seconds, no matter how fast we follow up shots.

Always remember that a 10-mph head wind takes over three minutes to get to you from 1000 yards so the wind you feel in the face is the past, not the future. It is not the wind your bullet will be flying in when you shoot it. Now think about a tail wind.

So, if we can’t always trust to have a shot’s feedback on the true winds, and the wind we have at the firing position is not the wind your bullet will fly in. How can we proceed?

How to Proceed

This sets up our first strategic decision we have to make when shooting ELR in the wind. Either we are required to achieve a cold bore shot, or we can live with a first-round miss. There is a strategy for each situation:

1. If we are required to achieve a cold bore shot, we will need to previously spend time analyzing the physical characteristics of the ground from our muzzle to the target, and prepare a plan, with multiple variations. Snipers and long-range hunters need such a dynamic plan, which takes into consideration that the wind can change over time and also takes into account the predicted winds and how these winds will interact with the ground and affect our shooting.

2. Most target shooters that are allowed sighters and those competing ELR with a good target background, can live with a first-round miss. These shooters will also make a plan and may even make custom wind tables for the possible conditions but will seldom spend the amount of effort the first group will. This is because, on many occasions, they will be able to use the best wind estimation available: their impacts.

For the first group you will need to previously find a topo map of the area, or Google Earth image, and a good prediction of the prevalent winds at ground level from any weather agency. If you add an isobaric map and hourly prediction you will also be able to predict how the winds will evolve during the day.

I have prepared a graphic of how I would predict the wind flow on some 2500-yards shots at Monster Lake Ranch in Cody WY, where I am bird hunting while I write this. This FFP (Final Firing Position) allows me to show on a simple-to-understand graphic how the wind would behave and how complex it would be to define its direction and strength just by observation alone.

Figure 67. Wind flow on complex terrain

From the FFP you would feel the wind like it’s coming from your 11 o’clock or even directly facing you, because you are directly on the area where the wind rotates to the west trying to flow to the valley after coming out the creek. In reality, the wind is only coming “facing” you for a few hundred meters and in reality, is flowing with a nearly crosswind component coming from your 8 o’clock for most of the bullet flight. On the last 300 meters or so, it does shift to a 7 o’clock tailwind for the last section of its flight.

Therefore, you should first measure the different sectors that divide what you predict the wind will do when you shoot. Then estimate the wind velocity using your Kestrel reading at FFP and consider that the central sector of flight will have a more compressed flow and therefore a higher wind velocity.

Applying the same wind VS terrain logic, think that wind climbs slopes and mountain sides so the resulting bullet deflection will have a vertical component that might be difficult to estimate. Just the opposite if the wind goes down towards the valley pushing our bullet down.

As you can see, this new wind reading takes time and knowledge, so it will take extra time and know-how. Once you have done your pre-shooting work you can jump to the last part of the process which is what the second group do, without the pre-flight complexities we just contemplated.

Cutting Corners

The second group will jump directly to the software input using a ballistics software that can input multiple winds and divide the bullet flight just by observation, in the three sectors. They will then input the wind speed estimate by watching how the wind would flow and comparing it to the wind reading from their Kestrel at the FFP (Final Firing Position). Basically, it’s the same thing the first group did, with a lower level of a planning. This group will miss the subtleties of vertical components, turbulences or possible rapid changes, but they will also get a good fire solution that might be good enough.

Either way, we can’t do much more now, and using these two approaches, the fire solution will then be as accurate as we, as ELR shooters, can predict with the tools we have today.

Conclusion

Whatever you do and no matter which of the two you decide to apply, if you don’t rely on a multi-wind ballistic software or, (worst case scenario) on a single-wind good ballistic solver, you don’t stand a chance to get first-round hits at ELR. Forget about paper tables for ELR as your shooting will become frustrating and misses common.

On the other hand, if you eliminate the unknowns by measuring all your shooting parameters, use a multi-wind solver and study the terrain interactions, you will have a lot of fun, enjoy the planning and execution of the shots and feel the Black Art of ELR wind shooting. This is not black magic, but a somewhat scientific approach to what many might consider impossible shots.

RICK ASHTON, AUSTRALIA

The first half dozen points you will get from most experts. They are about the basics and being properly prepared. The remaining points are some of the tricks that I guess you are looking for. The basics are the most important. Without them—nothing works.

Think in Terms of Value

The first thing applies to all wind shooting. Think strictly in terms of the value of the wind in points or MOA, but never, never, never think of wind in terms of change or of correction needed. Think, “I need 6 left!” Avoid thinking, “It’s up a bit. I’d better go a half more to the left.” It’s much easier to stay in step if you think in terms of actual values than changes.

Make Sure the Wind Zero Is Correct

The second thing also applies to all wind shooting. Make sure the wind zero on the rifle is correct. There is little satisfaction from getting the wind call right if it’s wasted due to a poor zero. Zeroing is not done by a single visit to the zero range. It takes time and must be done across the range from the shorts to the longs. It’s best done with a partner, going shot-for-shot in a variety of conditions, but hopefully around centerline—early morning can be good for this. But make sure that the partner’s gun shows similar sight movements as your own, or things won’t easily work out. The easiest way to make sure your partner’s gun “moves” as your own is to compare elevation differences from the shortest range to the longest range. This one comparison measures directly all the combinations of sight radius, chamber differences, muzzle velocity, load variations, etc.

Make Sure Your Sights Are Square

Make sure the sights are truly square, in a practical sense. This can be done by instruments in a machine shop but then ought to be tested on the range. I advocate setting up a long-range target, but shooting at it from close range, say 100 yards. Scale down the aiming mark to a size you can see best. (The idea here is to take sighting error out of the equation.)

• Fire a five-shot group at centerline at your normal 1,000 yards elevation. Have the marker pull the target, then carefully, using a spirit level, pencil in a perfectly horizontal line through the center of the five-shot group.

• Next, wind out left 25 points; fire five more shots.

• Then set the sight on 25 right and fire five more shots.

• Then return back to the centerline, down to 300-yard elevation, and fire five more shots.

Do not mark the target between shots; just shoot. When you’ve finished, the left group and right group ought to straddle the horizontal line, and ought to be the same distance from the centerline group. If not, record the differences. Also, if you were to connect the centers of the two groups fired on centerline with a straight line, that line ought to be perfectly square to the horizontal line drawn after the first group.

Why might this not work, even if set up perfectly in a machine shop? One factor is cheek pressure and cheekpiece design—crucial in long range.

Figure 68. Make sure your sights are square.

Shoot It Square

Having set the rifle up to be square, then shoot it square. I believe a spirit level is essential at long range to eliminate cant and the resultant “Burke’s bulges.”2 If the rifle still “wants to cant,” then fix (rotate) the buttplate until the rifle’s sights are naturally square to the target.

Use a Scorebook

Use a scorebook whenever possible/practicable and use it intelligently. One of the first really good books on shooting I read was the late Des Burke’s Canadian Bisley Shooting. In it he referred to the practice of “ranging.” I think that this is what long-range shooting is all about. We all seek precision, but when it comes to long-range shooting, the route that seems to take us closest is to acknowledge that there is no such thing as precision and to come up with practical tools to help eliminate or reduce bad decisions and help us make good decisions.

Set Up a “Proxy” Wind Flag

When firing in rear fishtail winds, if possible, set up a “proxy” wind flag so that there is a straight line between the proxy flag, through the firing point, in relation to the target in question. The proxy flag might be a team banner erected in just the right spot. It might be a streamer tied to a car aerial.

The tactic is to fire only when the proxy streamer is on the selected side of centerline. This can very much reduce the chances of “getting lost.” I reckon this cuts considerably the probability of wind-reading error. You need to be reasonably snappy with the shooting cadence, so as to get the shots downrange when the conditions are right. This also works in angled winds, either rear or frontal, when no “official flag” is directly observable for angle—simply adjust the position of the proxy flag so that it is in line with the mean wind direction and the firing point.

Favor the “Drop-Off”

I reckon that around two-thirds of changes in “fluky” winds are “drop-offs,” and one-third are “pick-ups”—therefore, if the wind is coming from the left, set your group in the right-hand sector of the center (or of the bull if it’s really tough).

Observe Others’ Shots

Use a wide-angled eyepiece if you can. A better change predictor than either flags or mirage is fall of shot. Observe the shots on the range as a whole (or of as much of it as you can see). This is indicative only but can help. It’s important to check the squadding on neighboring targets to ensure that the shooters who will share your time slot are worth watching— but don’t watch a particular shooter; watch the range.

Use Mirage

Always check mirage—but be careful about how much you factor in its effects. Use a low-power eyepiece (15X), if you can. This will give you a deeper look at mirage; a higher-powered eyepiece might pick up more mirage, but it will tend to be at a localized point on the range.

Put the target in the bottom of the scope’s picture at long range. The bullet’s trajectory is well above the line of sight— you should be looking high in the scope for the mirage. Do not fire if mirage is “swirling,” even if there is no apparent change to the wind flags—a “mystery” wind, elevation, or corner shot may result. Be careful about firing points downrange when reading mirage at long range. Sometimes the only mirage you’ll pick up is that on top of a shorter firing point; it will be very localized and may be unrepresentative of what’s happening in total. Place low weighting on mirage in frontal fishtails.

Maintain Composure

Maintain as much composure as possible, even in the tough stuff—an inner on the waterline is better than a magpie in the corner.

SERGE BISSONNETTE, CSM, CANADA MEMBER OF DCRA HALL OF FAME

My First Exposure

Just to lighten your day, I will share with you my first exposure to scientific wind calling.

In 1977, I was part of Mike Walker’s team to New Zealand (adjutant) and came across a colorful Kiwi from Greymouth named Morley Callahan. Morley was not a big hitter, but during the NZ-NRA Grand, he posted a 49/50 at 1,000 yards, with conditions that only New Zealand’s Trentham Range can stir up. He was a clear four points ahead of the second-place shooter, with the average master score being 41/50.

Everyone was asking Morley what was his secret in deciphering the winds. Morley advised that when he was placing his equipment down on the firing point, he split the rear seam on his trousers and did not have the time to change them (knowing Morley, he wouldn’t have changed them anyway).

His clear and concise instructions were: “Every time I felt the wind up the tube, I shot.”

I don’t know the exact tear size, but it does give credence to mother’s advice on wearing clean underwear.

Wind-Judging Drill

1. Show up behind the firing point and do the pre-shoot analysis:

A. Look at the lay of the land to see if there are evident features that may contribute to or interfere with the consistent flow of air, such as a tree line (“A” Range, Connaught), a hill (Homestead Range, Calgary), or a ravine (St. Bruno Range, Quebec).

B. Look for patterns of air flow; compare wind flag pitch and angle with the mirage.

C. Check wind chart for parameters when there is a strong condition and when there is a mild condition. If stable, the job is easier.

2. Take up the shooting position:

A. Lift head and feel the breeze; most times it’s different than when you’re standing or sitting.

B. Confirm pattern; look at grass for low movement and flags for high movement.

C. Note angle and mark on “call” section of plot sheet.

D. Scope the mirage; off-focus target, about 100 meters front of target.

E. Mark the SWAG, your best “scientific wild-ass guess,” on your plot sheet; and sight which should be in line with your wind chart.

3. Fire the shot:

A. Sight alignment—confirm “feel” and flag.

B. Sight picture—confirm “feel” and mirage.

C. Execute the shot; focus word; follow through; call shot; mark my call.

D. Confirm conditions—flag and mirage.

4. After the signal, do the following:

A. Graph—compare graph setting to wind chart for difference. This is to have a reference in case of a big change. If you rely only on your wind chart and do not calculate the “error factor” on this particular shoot/range, it costs you points to reconfirm a known.

B. Adjust—return to 2(A).

BERT BOWDEN, AUSTRALIA WINNER OF THE QUEEN’S PRIZE, AUSTRALIA (THREE TIMES) PALMA TEAM CAPTAIN (1999, 2003)

In selecting our coaches for Bloemfontein 1999, we would ask aspirants two questions:

1. What wind do you think is on now?

2. How did you work that out?

Responses to the second question caused shudders. Nobody did it in a consistent way—because they’d never been taught, but rather “picked it up” or worked on “gut feel.” Our current PALMA team is now training juniors as our future coaches.

[Authors’ note: Bert kindly sent us his entire wind-reading lesson plan, which covers the topic most thoroughly. The following shows that we have shamelessly stolen the best, and abbreviated the rest.]

Before we get on to wind reading, I must emphasize that there are some very important elements of preparation that are absolutely critical to good shooting. But more important, they form the basis for becoming confident at reading wind. They are:

• Make sure your rifle is properly zeroed and that the sights are shooting square by shooting a plumb line.

• Make sure your plotting and sight setting are perfectly accurate and that you analyze every shoot immediately afterwards.

• Make sure you can shoot the smallest possible group and that your group is in the middle of the target.

There are four ways of attacking this difficult, but mostly conquerable, thing called wind. The shooter may be able to use one of these approaches throughout a shoot, but on occasion it may be necessary to change approach mid-shoot. It is one thing to start with a plan, but be ready to change to another plan if the conditions dictate. The four approaches are:

• Shoot fast, correcting on the last spotter.

• Treat every shot as a sighter.

• Select a single acceptable condition.

• Play the percentages.

Shoot Fast, Correcting on the Last Spotter

In difficult conditions, do not use this method. This method is best suited when conditions are steady or when winds are changing evenly or slowly.

You will often hear it said on the range during extremely bad conditions that the only answer is to shoot fast, correct on the spotter, and beat the changes. This is fraught with danger and a recipe for embarrassment. Don’t do it!

The fact is that conditions can change quickly, and even much more quickly than you can shoot. What happens is that you finish up “chasing” yourself all over the target, correcting on bad shots, and suddenly you find yourself neck-deep in trouble.

Treat Every Shot as a Sighter

This method is best suited for the following:

• When conditions are difficult, and an appraisal before every shot is necessary

• When “surprise” conditions are apt to occur

• When shooting two or three to a target (Bisley style)

For those who are confident wind readers, this is where they put their trust. In difficult conditions, a confident wind reader will calculate the setting required, get ready, take aim, check again before firing, and if correct, fire quickly. The essence of this approach is in firing quickly, but only after you are sure of the wind setting.

The one time when this method becomes mandatory is under conditions such as those experienced at Bisley, where there are two or three to shoot on the same target. There, it is most essential to follow the changes in the wind, sometimes making alterations while the other two are firing a shot each, just to keep in touch with any changes.

The one thing that becomes apparent here is that you will always know in terms of how many points (minutes) or windage you have set on the sight. Never, ever, get into the habit of saying that “it’s up a bit” or “it’s down a bit.” That’s not wind reading; that is trying to guess the differences!

Select a Single Acceptable Condition

A recurring condition is one that you expect to keep occurring, and, if you intend to use this method, you must choose a condition that is expected to occur most often. There is no point in selecting a condition that will happen only once every 10 minutes and be there for, say, 30 seconds. What you want is a condition that will be there for the majority of the time, and preferably stay for the longest period.

This method is best suited to the lapsed-time method of shooting [such as in smallbore matches and in ISSF 300-meter matches].

A recurring condition might be a flag in line with a pole, a flag on one side or the other of a pole, or any flag that shows a constant condition.

Play the Percentages

With this method, it is usually as a result of observation of the conditions before you shoot. You should get into the habit of always observing before you shoot. For at least 15 minutes before your turn to take the mound, you should preferably sit behind a line of flags, with your telescope firmly in hand, and check the variations in mirage and flags. During this time you can determine what sort of approach you will take, based on your observations.

If you decide to play the percentages, what you have observed is that all the changes (if there are any) are not enough to put you out of the bull. For example, there may be a steady 3-point crosswind which occasionally flicks up to about 4, but that’s all. On that basis, with your sight set on 3½ points, you could comfortably shoot at your own pace and expect the group to wander from one side of the bull to the other. You must always check, though, before you fire every shot. Remember that wind is fickle, and the one you don’t check before firing is the one that will get away on you.

Three General Statements

1. A shooter who fires a shot without being sure is letting the conditions master him. Strive always to be master over the conditions!

2. Everyone starts each competition equal (that is, with the possible number of points). Throw nothing away.

3. Everyone makes mistakes. Strive to make fewer mistakes than your opposition.3 If you make a mistake, always work out why and strive never to repeat it!

The Bowden Method

A flag will always show an “approximate” condition. It is nearly impossible to judge exactly from any flag, and you will notice if you read up on findings from studies of wind effect in shooting, that there’s almost a sixth sense required that tells you the calculation should be just a touch more or just a touch less. So, out of it all we learn to read an “approximation” in the flags until it becomes second nature to us.

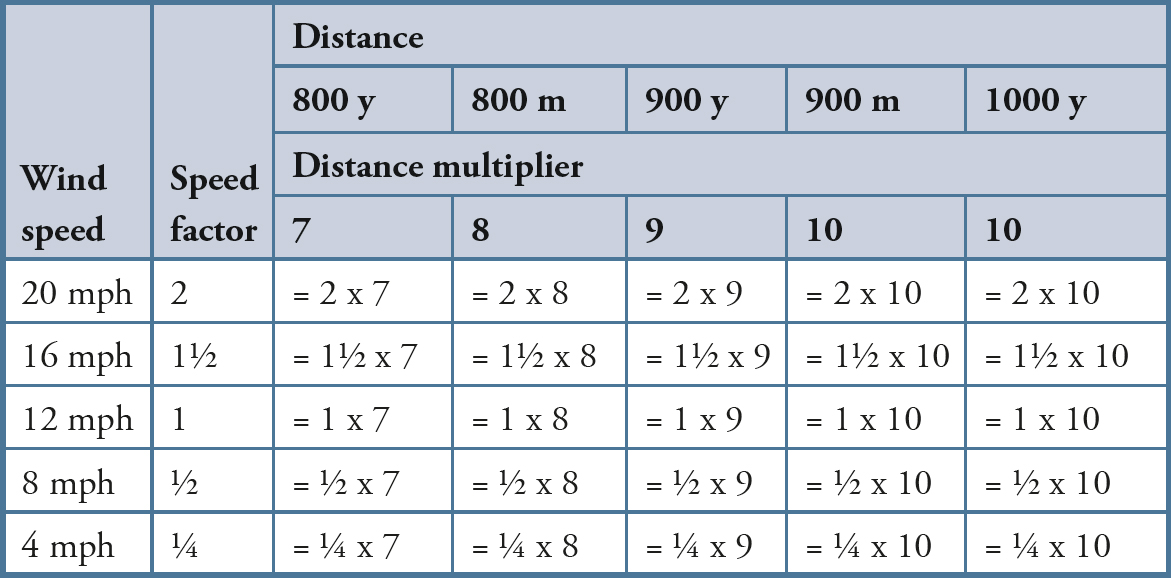

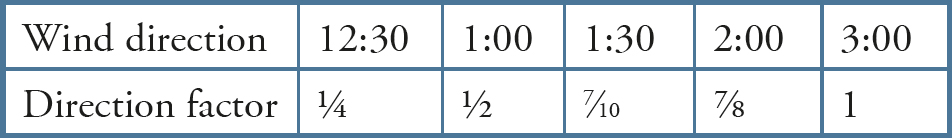

Figure 69. Speed factor chart.

Figure 70. Direction factor chart.

In his book Competitive Rifle Shooting, Jim Sweet recommends a comprehensive table of estimating wind shown on the flags in mph. Employing the KISS principle, I use a variation of a method that Clive Halnan has written about. The wind speed is read from the position of the flag tip, and the speed factor is applied to the distance multiplier. In effect, the shooter need only memorize the speed factor and the distance multiplier in order to calculate the wind settings.

These are effectively the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock sight settings for all distances. Let’s go on with direction allowances. There are four additional figures to be used as direction factors, and with thanks to Jim Sweet, here they are shown in Figure 70.

Mirage

First, what is mirage? To you, the shooter, mirage is wind that you can see through your telescope. To those who study atmospherics, it is the result of the disturbance of air, layers of different temperature, or eddies. To me, mirage is a most important aid to your shooting. It is also the prime reason for owning a good telescope, 25-power or better.

Here are some basic points about mirage:

• It can’t be seen when light is dull.

• It is of no use for winds over 8 mph (13 kph).

• It can be a trap in varying light.

• It can change in either strength or direction.

• It can be used to complement or confirm flag readings.

How do you see mirage in the first place? Basically, focus your telescope on the target. Then defocus toward you. That is, focus on an imaginary point between you and the target. What I do is focus on an object about one-third of the distance down-range. (For example, if I am shooting at 900 yards, I focus on something at 600 yards.) Then I swing the scope back onto the target. I’ve found that this approach gives me a consistent way of getting mirage pictures at the point in flight where the wind effect is most relevant. This way, I see (at a particular distance) what I usually see.

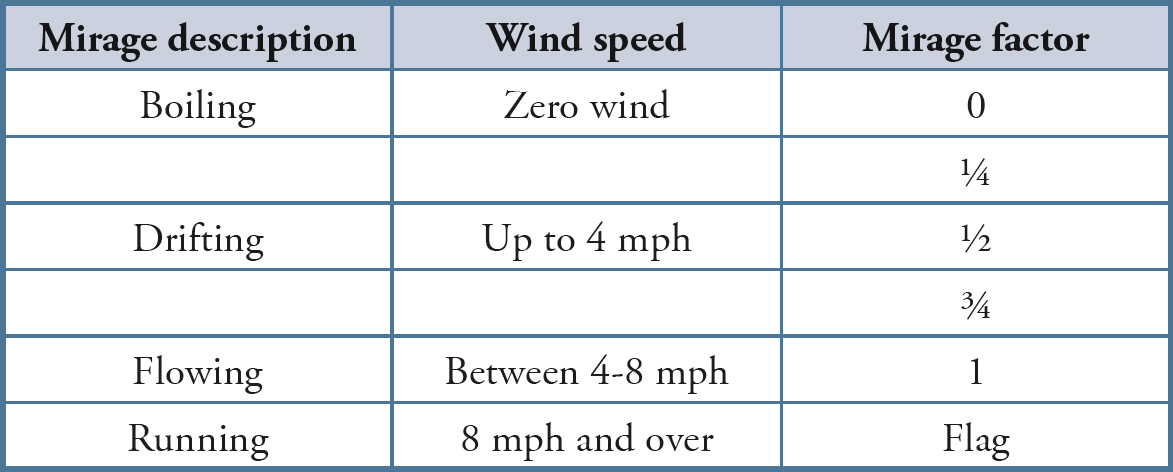

Figure 71. Mirage factor chart.

There are four basic stages of mirage, listed in Figure 71. Mirage factors can be applied to the distance multiplier the same way that speed factors were applied earlier.

If mirage is present, check it before every shot. Position the eyepiece of your telescope so that you can check mirage without having to move from your firing position to do so.

Other Wind Factors

I want to emphasize that the wind allowances that I’ve mentioned are based on having all flags along the range indicating the same thing. Those of you who have been flag-watching will already know that this is a rare phenomenon. More often than not, no two flags show the same strength and/or direction. In some cases, they can show wind from both sides at the same time, as happens on some of the more infamous ranges like Canberra’s McIntosh Range.

When you run into this situation, you have three choices:

• Ignore it, do nothing, shoot again.

• Take a guess, do something or nothing, shoot again.

• Calculate it as near as possible.

What do you think is the preferred thing to do? Right: calculate it as near as possible. Remember, wind reading is about knowing; guessing has no place.

General Tips

• Always calculate, never guess.

• Develop your shooting rhythm to aid wind reading.

• The shot on the left or right is not necessarily because of a wind change.

• If it’s raining, the flags will probably be wet; be aware that they won’t show the full allowance.

• Rain is like a wet mirage. The angle at which it is falling can be an aid to wind reading. Check through your telescope.

• If you are having trouble with the wind, so are most of the other shooters.

• Don’t “creep.” If the conditions have changed and you’ve calculated a move, have the confidence to move the sight accordingly.

• It’s best to use a flag that’s showing wind coming toward you, rather than one showing what’s already gone.

• God planted trees and grass to aid shooters. Use them to detect when gusts and other inconsistent conditions are occurring.

• Never fire in the middle of an obvious change (or gust). Wait for conditions to settle, if match conditions allow. Use the rules to advantage; challenge your last shot if you need to gain more time.

• Never move on another shooter’s spotter. He’s more likely to pull wild shots than you are.

• If confusion sets in, stop and recalculate.

• That last, quick check of the flags before releasing the shot is worth its weight in Queen’s badges.

• More possibles are made with steady, deliberate shooting than with hurried panic.

DON BROOK, AUSTRALIA

Why This Is a Difficult Question

I was asked to coach the army Under-25 team in New Zealand, at 1,000 yards, and when I questioned the two top army wind coaches about what they thought the wind was doing and how much was on, I was presented with “I’m blowed if I know.” So, we split it three ways: one went with 32 right, the other with 28, and I went with 24. Thirty-two produced a dead-center bull, while the rest of us missed it!

When I asked what he had done to work this out, his curt reply was “I really do not know; it just looked like 32.”

How can you promulgate that sort of reply?

So I know what you are up against. There are so many wind readers out there who just rely on a millennium of experience, but cannot write or teach it.

In my case, I have had access to the finest smallbore shooters in the world, blokes who can explain, and I have learned heaps from Ernie Van De Zande and Lones Wigger Jr., and then worked very closely with one of the best sports psychologists I have ever seen in how to approach the wind problems within the mind and make a decision based on the facts that confront the shooter.

I can relate one instance when I fired a prone 60 shots in Linz in Austria, in the most horrific wind conditions I have ever fired a smallbore match. Ernie Van De Zande fired a 600, which absolutely astounded me, while my own score, a 592 (with a 100 in the final string), ran second. Ernie and I spoke for five hours over this, and when I could get back to my hotel, I wrote it all down. That bloke fired that match in absolute genius mode, and we were the only two shooters over 590 points.

A Story About Where Wind Knowledge Helped Me

I am not sure what you want, apart from some instances where wind knowledge helped me. With this in mind, here is one you may be able to use that happened to me a long time ago, in the days of my .303 rifle.

I was in a big shoot-off for an 800-yard match in the 1969 NSW Queens. Forty-two other blokes and I all had 15 bull possibles! We all lined up on the mound with the flags hanging dead down the poles in the pre-calm of an approaching southerly storm on Anzac range in Sydney. This storm looked really ugly coming in, and my pre-match thinking was to get my shots down the range about 10 feet apart! We started, and I fired two sighters, both in, and three bulls pretty quickly, when the wind hit, and how! Poles were bending with the flags looking like they were starched. Just as the wind hit us, a shooter on my right, who ultimately went on to win the Queens, fired his second shot. I was wondering just how many points were required in this enormously strong storm, when my target went down and was marked an outer, on the very edge of the board at three o’clock. I told him he had shot on my plate and was met with a curt reply, “Bulldust.”

So, here I was thinking perhaps 35 points in the change, when it hit me . . . I altered my sight five points left, aimed at his target, and hit mine smack in the middle! I shot the only possible on the range, with the last two shots aimed on my friend’s target on the right, with five points left on the wind arm, won the match and 25 quid for my thinking.

I was pretty chuffed with that!

On the Virtues of Aiming Off and Shading

The fastest way to combat wind deviation is using the aiming-off and shading-the-aim routine.

Aiming off is “big increment” stuff, to even off the target. Lining up the side of the target with the exterior edge of the ring gives you about 10 minutes of angle, depending on the range being fired. Obviously, edge sighting at 300 is a heap different to 1,000 in terms of minutes.

Shading the aim is very fine increments, even to nominating a shot within the V-ring, and largely this type is positive thought, induced by command to the subconscious mind.

I found, in smallbore aiming, that with training I could aim so accurately with this, I could nominate a 10.1 at clock rotation, and shoot out the bull in 12 shots going around the clock. I can aim within the 10-ring anywhere I want to put the shot, and this is very valuable wind combat stuff. Does this lot scare you?

To be fair, I do not know of any elite-level smallbore shooter who cannot do this, and many utilize the bubble cant as well as a wind combat method.

These are just more tools in the bag of tricks. Lately, I have been perfecting techniques with the electronic computer systems, and these really sharpen up the aiming process.

More on Aiming Off and Shading

Teaching this to the army squad created an enormous amount of controversy, as nearly all the fullbore shooters I have come into contact with are reticent to adjusting the aim away from dead center. Smallbore shooters and elite-level 300-meter shooters are way ahead in this area.

We have a range in Australia (Canberra, where the National Queens is staged every year) that is extremely fast in wind variations, both in increase and decrease, plus direction changes. Mirage also overrides any small variations. This range can be very difficult, and introduces a psychological barrier as well. Mostly the shooters get carved up in a big way because of their inflexibility of aiming.

I taught our army squad to circumvent this by the psychological attitude that they are the boss. The rifle will never shoot Vs while it stands in a corner, eh? In order to teach this, obviously [I had to do] a lot of groundwork in wind reading, particularly in Canberra, where the range slopes sideways about 10 degrees to the right. This alters the plane of wind effect from normal, to be roughly parallel with the ground.

In learning to shade, or aim off either uphill or down, they have to have the confidence to try this method. The rifles need to be zeroed exactly (as should be the case anyway). Most of my squad had a tough time in gaining the control to muscle the rifle slightly, to effect the required aim, but soon got over the problem when the central bulls arrived. Funny, that!

To outline the thought process for you requires a scenario for you to imagine. I often shoot on another range in Australia (Mudgee) where the sighting in the morning is as crisp as glass, and I was down early with the early-morning wind at half value. After getting the wind zero directly into the central at 10 o’clock, as I maintained the wind would increase rather than drop off (I was correct). I proceeded to aim where I wanted to in the method of combat upwind. In other words, showing a full bull in the aim toward 10 o’clock in the ring sight. (The aiming mark was at 4 o’clock.) I try to visualize a fine set of crosshairs, so I can be really accurate where I put the aim. As the shoot progressed, I needed to sharpen the wind assessment in value and vary the aiming accordingly, so the continual judgment was as clinical as I could put together.

The shoot flowed along very quickly, as it happened, and I was off the mound, with a match-winning 50.9 in 6 minutes. One of my club mates mentioned to my wife, Cheryl, who was watching: “Look at that, he shot right through then without touching the sights. What a lucky patch!” I didn’t tell him I was shading the aim, on at least six of the ten shots.

As a footnote, the club mate went down later and tried to battle the wind variations. He was slow and wound up with a 48.3.

The method works, but you have to have the courage of your own convictions with reading the wind, analyzing what is out there, and using the combat method you decide on. The thought processes I employ are very clinical in assessment, and I will often move the sight back to wind zero, and make my own new adjustment, on the value that I think is out there based on many and tried observation techniques . . . assessment of direction in the half-value winds, flag ripple speeds, and tip elevation in full-value winds. This is not just an accident of years of learning; it is a very exact science. There are mathematical geniuses in our sport who quickly assess the values using cosine and even trig to arrive at the assessments.

JIM BULLOCK, G.C., CANADA MEMBER OF DCRA HALL OF FAME

A River of Wind

More than once I have seen wind flags pointing at each other. The wind is not an even flow of air like the water in a slow, wide river. As our bullet goes downrange it passes through patches of air moving at different speeds and at different angles. The displacement we see on the target is the average result of all those influences.

Each few seconds, the effect of the wind influence changes. Have you ever finished a match in which you struggled with the wind, while the cadet beside you shot well and proclaimed, “I never touched my sight!”? The wind keeps changing, and for one shooter it can change back to the same condition each time it is his turn to shoot.

Let’s consider wind strategy in several steps.

Before the Match

Arrive early, pull out your Parker Hale whiz wheel, and follow the wind for a while. The flags will give you a feel for the approximate average direction and strength and a feel for the magnitude and frequency of changes. The wheel will give you a feel for the number of minutes associated with a change of direction or strength. This helps you mentally “change gears” as you move from one distance to another. At 600 yards I would say to myself, “Okay, if I see a change, it is at least a one-minute change.”

As shooters leave the mound, ask them, “How did it go?” Some will give you a detailed explanation of the key flags, the wind shifts, and magnitudes of change. Look at their plots, if possible.

During the Match

Mirage is the best indicator of wind. Focus your scope on a mound 100 or 200 yards in front of you. If mirage cannot be used, the best flags are the ones close to you and upwind. Another excellent wind indicator is the shots of other competitors. If you see a number of downwind inners and magpies, you know there was a shift that caught them.

If the conditions are changing frequently, a Plot-o-Matic (EZ-Graf) quickly shows the extremes of the changes. I find it easy to write in a little arrow, showing flag angle, and a little picture of the flag to show strength, beside each shot number. If the wind fishtails, the zero sight setting will be between two flag pictures showing the wind going in opposite directions. If there is a major change, you have a pictorial reference as to wind strength and angle to refer to. This is very handy if you have to come back to a condition that occurred much earlier in the match.

I once struggled at long range, making major changes, only to find that I had two settings on the rifle—too much and not enough. After the match I looked at George Chase’s Plot-o-Matic (EZ-Graf). It was obvious that although the wind kept changing, it was changing from a strong right wind to a mild right wind, and that if I had shot the match with 11 minutes or 4 minutes, a possible was there to be had. George almost had the possible, because he quickly recognized that there were only the two mean wind conditions. I was so busy reading the wind I did not catch on to the reality.

Shooting is a game of averages. There is an average wind, made up of strong and mild components. There is an average group, made up of an extreme left and extreme right aiming and ammo component. It is a mathematical certainty that the best score will occur when the group is centered over the bull. Even if you miss a wind change, there is a good chance of a bull if the group is centered. If it is a quarter-minute high or low, the bull is much smaller. If you find yourself thinking, “The last four shots are a bit high—if this one is high, I will come down a quarter,” then you are probably not being as diligent as you should be with your group centering. Centering the group makes the bull bigger.

There are other wind indicators that can be used in some conditions:

• On a very, very light wind day, especially if there is a fishtail condition, the muzzle smoke indicates which way the wind is going. This is handy when there is no mirage.

• Tossing a tuft of grass in the air can show a light wind direction.

• A lot of inners out the same side of the target is a sure sign something happened.

• Watch your shooting partner’s shots. An upwind or downwind inner may be a perfect indicator of direction and magnitude of a wind change. (Or it may mean a bad shot. Check other targets.)

Wind Reading

An understanding of wind is necessary in order to develop a strategy to handle it. I started this article by saying, “As our bullet goes downrange it passes through patches of air moving at different speeds and at different angles. The displacement we see on the target is the average result of all those influences.”

At long range, we must take into account the air mass passing through a large box of air in front of us. A gust of wind on our cheek may be quite irrelevant, given all the air in front of us. One of the assets we have to work with is a few seconds of time allocated for the shot. Assuming you can see several flags, make it a rule not to shoot until all the flags are going the same direction. The angle may vary between flags, but don’t shoot until the box of air in front of you (or the box of air moving toward you from the upwind flags) is all moving in the same direction. If you shoot in a swirl condition, it is a temporary condition that is difficult to read and even more difficult to record for future reference. In practice, this means that most of your shots will be fired quickly, and occasionally you will need to use most of your 45 seconds to let the wind stabilize.

After the Match

We all have some ability to see a wind change and then say, “That’s a two-minute increase,” and then take the shot. After each match it is useful to do a postmortem and analyze how accurately we made the wind changes. One thing I do is note the times I made a wind change based on an observed wind change (as opposed to a group-centering adjustment) and mark the change with a + or a - depending on whether I over- or under-adjusted. If I have a lot more minus marks than I have plus marks, then I know I am being too tentative in my changes. If you tend to over-adjust at short range and under-adjust at long range, this little exercise will quickly expose the problem. I also mark with a ? when I have made a change that seemed uncalled for. A lot of question marks means I am trying too hard and seeing changes that are not there.

GEORGE CHASE, CANADA MEMBER OF DCRA HALL OF FAME

What you are about to receive from shooters around the world should make for an interesting read. The mind-set of American shooters, with their style of string shooting, should be very different from the pairs, and even three to a target, of the English. With the world becoming so small, with the use of computers and the group sizes following the same course, I will look forward to the final production of your wind book. Yes, it will make an interesting read.

Lights started going on for me when I began using a plotting board. I was a poor recorder of useful information using the plot and graphs. The board began to show me how few changes there really were on the range. It showed me the difference between wind and mistakes, and constantly told me to center my group; with the true picture I became more comfortable and confident. With confidence came smaller groups.

In a conversation with one of Canada’s better shooters I asked the question, “How would you go about picking a wind coach?” and without hesitation he replied, “If we had access to everyone’s plotting cards and we knew they were honest, I would simply choose the shooter with the biggest groups and highest scores.” World-class shooters shoot small groups. Great wind coaches are, for the most part, made that way by great shooters and great conditions. I’m sure within the pages of your book you will answer questions on all aspects of the wind. Those who can cope with all their minds can cram in and make a decision on what to do while shooting a small group will be the winners at the end of the day.

Your plotting board or sheet should be your greatest aid in reading varying conditions. Being able to return to the same sight setting for a similar condition is not something for which you should rely on memory or a best guess. Plot as accurately as possible and you will be amazed how the range settles down.

I think it’s impossible to separate wind reading and group formation. When the wind is switching from 7 right to 7 left, shooters are going to come away with poor scores. There are some that may pooh-pooh a 5- or 10-minute change, but scores will fall. It’s when the changes are gentle that we must be aware of all our little mistakes that we attribute to wind; these hurt our scores. Sometimes we are looking for wind that is not there. In the pre-F-Class days, I was shooting with one of the finest gunsmiths in North America; you knew he had the finest equipment available. We were at 800 meters, and his score was not impressive for the conditions. The very next year, same match, close to the same conditions, he shot a 50 with 10 Vs. Did he have a bad shoot the year before? No, he shot his average score. Did he, in one year, learn all the deep dark secrets of wind reading? No; what he did with the aid of a scope was to stop chasing sighting errors.

I know the greatest evaluation of what’s happening on the range is the shot placement on the targets. Read the targets, at least six, quickly evaluate the center of mass, make your change, and shoot.

STUART COLLINGS, GREAT BRITAIN

I have always thought that wind reading is a black art and that most coaches don’t really know exactly how they do it. Sometimes they are in tune with it, and sometimes they aren’t. It depends, among other things, on their mood, time of the month, the type of wind that day, and, of course, the quality of the shooter. As far as tips and pointers go, I can think of a few.

• At long range, think of the wind as a body of air moving across the range from muzzle to target. I don’t subscribe to the view that wind at the firing point end is necessarily more important than wind at the target end.

• Judge an absolute value for the wind for each shot rather than going purely on an estimate of how much it has changed since the previous one.

• Get a fix on speed and angle on an upwind row of flags running down the range, and after the decision get the shot away with the same rhythm each time. If the nearest row of upwind flags is 10 targets away, the rhythm may be slower. If it is just alongside, you need to get it off quickly. Bear in mind, though, that the wind can sometimes billow down from above along a broad front and can lift several flags across the range at the same time. Also, if there are only a few flags down the range, then a gust can zip through between them. Tricky, eh!

• Don’t always believe fall of shot on your target. Be confident of your calls.

• Team wind coaching is a team effort. Use information from your other targets constantly.

• If flags and mirage disagree—stop.

KEITH CUNNINGHAM, CANADA MEMBER OF DCRA HALL OF FAME

For most of my shooting career, I have never had a plan about reading the wind. I tried to get information from other shooters before I went up on the line, studied charts (guessing at wind speeds), and from then on it was more of a reactionary shoot.

It wasn’t until I went to the World Long Range Championships in South Africa in 1999 that I actually went onto the line with a plan. I knew what the bookends would be and which flag(s) I was going to watch. I knew whether this was going to be a direction shoot or a wind speed shoot.

I like to arrive at my firing point at least a half hour before I am to shoot. I now use a wind meter, which tells me at what speed the wind is really traveling. For years I would go out and look at a flag and only guess at the speed; not ever having actually seen a flag that I knew was flying at 10 kph, it was impossible to say for sure that this flag looks like 10 kph. With the wind meter, I can now learn to recognize wind speed much more accurately. One is not allowed to use the wind meter on the firing line during a shoot, but during my preliminary study I memorize the flag condition as it relates to the wind meter reading, so that I can recognize this condition as the primary one and relate it to other conditions if I have to shoot in the changes.

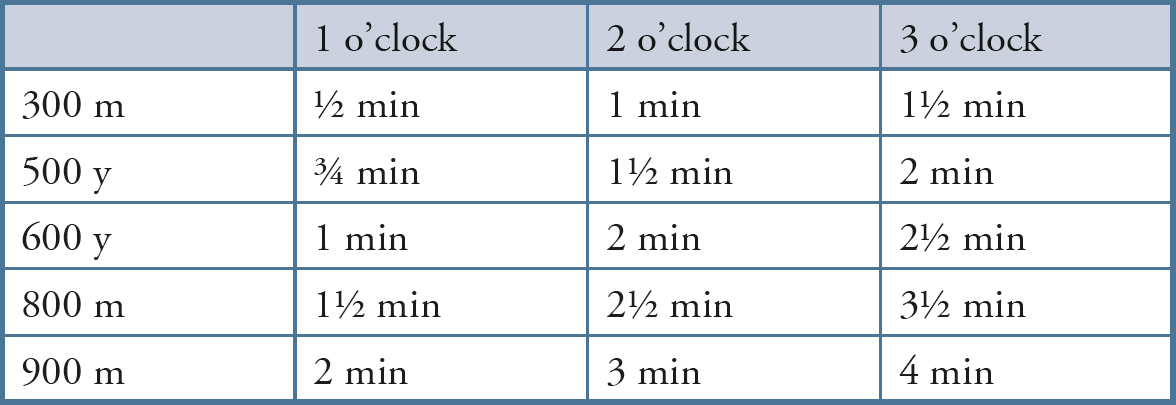

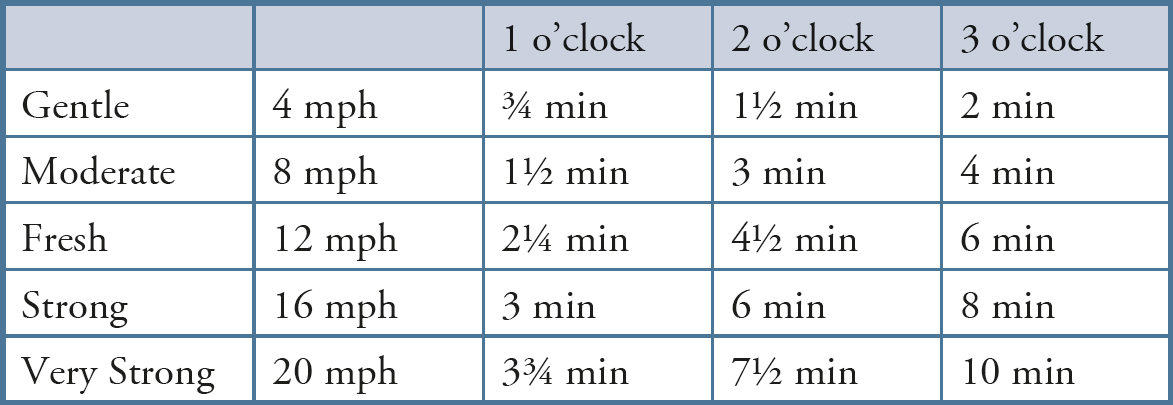

Once I have studied the wind direction and speed for a while, I refer to a set of charts, which I find are simple and easy to read, for my initial setting. Linda and I came up with these charts and teach them on our police sniper courses. I wanted to provide the police with something that minimized the number of pages they had to carry around, and was straightforward and simple to read. I have always found that these charts will, at least, keep me in the inner and near the bull, with my opening shot.

I fire my sighting shots as carefully as any of the other shots. These shots are not “just sighters,” but shots from which I am going to get a more accurate reading of what the wind is really doing in this condition. I memorize the flags, both for speed and direction, and now know what should be on the sight for that condition. I use a Plot-o-Matic (EZ-Graf) to plot my shots, and as long as the wind stays in my memorized condition, I know what I should have on the sight.

For each shot I go through a little “ask the question” game to help me come to a decision about what the sight should be at for the next shot:

“Is the wind the same or different?”

If it is the same, I carry on with what I know.

If it is different, I ask another question: “Has its value increased or decreased?” This will tell me what direction I am going to change the sight. Then:

“Has it changed a little or a lot?” This will get me mentally prepared to make the correct amount of change. I then refer to my plot to see what the bookends have been and decide if this condition is outside or inside those bookends. I also have a look at the other targets to see what the average error is on those targets, to get a feel as to how much I should change. I then make a decision, set my sights to the specific windage, and fire my next shot.

One point that seems to help: after each shot I see where my shot landed and immediately make a sight correction to center that shot. To help calibrate my thinking, I say to myself, for example, “Okay, that’s the wind condition that needs 2 minutes left.” And then I decide what my next sight setting will be from where the sight is now set. This reestablishes my baseline position and helps to keep my group centered.

To summarize: find out quickly what you need to have on the sight for a certain condition, memorize the flags or mirage appearance for that condition, and make future decisions from that known point.

CLINT DAHLSTROM, CANADA

To shoot a long-range bull’s-eye, the shooter has to do three things very well:

1. Previous shots must be analyzed to coordinate wind judgment with the realities of the day and the range.

2. With that calibration of judgment, observations of current conditions must be converted to sight settings.

3. Then a perfect shot must follow that sight adjustment very, very quickly.

Every shooter has a personal procedure for executing each step, and that is just as it should be. The critical thing is that these must not be three separate activities—they must be part of a single, integrated whole.

The shooter must have a standard program that naturally progresses step-by-step, without omission, from recording the last shot to firing the next. The shooter’s mind-set has to be such that a typical step description goes like this: “Immediately after clicking on the wind, I always center my target number in the aperture and then come down (or up) to center my bull in a perfect sight picture.” It is critical that the attitude be such that the word “always” pops out naturally, in describing the transitions from analysis to wind decision to shot release, because those transitions are the weak link in most programs—where momentary inattention or other poor execution may allow errors such as missing a wind change or shooting a V on the target next door.

Additional Words of Wisdom from Clint Dahlstrom4

The following advice is intended for folks who think they can substitute wind judging for good “holding and squeezing.”

It is easy to say that one needs an efficient personal system, but developing it takes a lot of time and dedicated effort. For those lucky enough to have a mentor, such as a parent in a shooting family or a dedicated coach in a local club, the task is easier (but still not easy). However, many of the very best attained that status without the advantage of mentor assistance. A common, and quite practical, program is to start by rather slavishly imitating the masters. Without being overly intrusive, one can learn from them effective procedures with which to build a basic program by observing and talking and reading. After substantial progress, perhaps to mid-master level, one may begin to suspect that, while the basic principles are surely valid, some of the procedures employed by the very best are “individual-specific prescriptions.” Optimal shooting programs are not a one-size-fits-all proposition, because people differ in physical and mental attributes. The next stage, then, is to identify and incorporate those modifications that will aid in delivering the very best shots that one can fire.

As a simple example, consider ISSF prone shooting at 50 or 300 meters where many (most?) of the elite use “shading” or “holding over” techniques in coping with certain wind conditions. Confidently effective use of these techniques requires the crisp, clear sight picture provided by excellent visual acuity, and fully functional focal accommodation. Those with imperfect visual acuity, and/or at an age when focal accommodation deteriorates, usually see a fairly clear aperture and a fuzzy bull. This is not optimal (acceptable?) for holding over. However, these are not definitively hopeless conditions. One must simply find another way.

By itself, the primary stage of fully understanding and carefully applying the basic principles of marksmanship will produce a much better than average competitor. In going beyond that stage, the devil is in the details of analyzing one’s physical and mental attributes and developing accommodations, within the basic principles, that will optimize personal performance. This is a critical stage. Make no mistake—one cannot hope to be a long-range winner without developing the “holding and squeezing” skills necessary to be a consistent short-range contender and frequent winner. Developing an effective wind-coping system is part of the third-stage graduate course that permits one to benefit from superior marksmanship. It is an essential supporting function. It is not a substitute for flawless shot delivery.

All the champions you admire and hope to emulate have been successful in their personal multistage development campaigns. Those with a talent for teaching do remember the struggles needed to attain the competence they now enjoy. These folks can and will help. Others have abandoned the memories of their development struggles as excess mental baggage and have allowed their subsequent successes to convince them that their current procedures are the universal “right way.” This conviction is something for students to cope with now and to remember when they have earned the right to pontificate.

It is easy to lose a competition by inadequate performance in the early simple stages. To win, one must stay with the best in the early stages and then excel in the difficult stages. In multi-range prone rifle matches, the long range is the definitively difficult stage, and usually it is wind judging that determines the winner. To be a consistent winner, you must put a very high priority, and a hell of a lot of dedication, into developing your own best possible system for shot delivery and wind coping.

DARREN ENSLIN, ZIMBABWE AND AUSTRALIA INDIVIDUAL WORLD LONG-RANGE RIFLE CHAMPION (1999)

I have been thinking a lot about your book. It certainly is a book on its own due to the complexities of “weather” on a projectile. I am just going to write from my head on the subject. I may sway from things you may want to hear (i.e., common knowledge), but it will be easier for me, and then you can take out and use the bits you want.

I totally agree that weather reading is a learned/subconscious action that tends to get better with time, practice, and confidence on a particular range.

Weather reading (for me) comes in three thinking phases:

1. Shooting a string (single shooter)

2. Shooting in pairs or threes

3. Coaching a shootist

Shooting a String (Single Shooter)

When I shoot by myself in a string shoot (not being coached), I feel my most relaxed. I know that if I shoot fast, which I have the confident ability to do, then I can keep up with the weather and follow shots, and be able to trust that 3 or 9 o’clock shots are weather patterns.

Changing on What I Call the “Future Wind”

I call it this because a lot of people look at the line of flags very close to themselves. By the time you’ve adjusted for the “present” weather close to you, aimed, and pulled the trigger, it has blown away, and the weather affecting the flags two to three ranges across (the “future”) is now with you.

This method contributed to my successful performance at the World Individual Long Range Championships in Bloemfontein. There, the strength in the wind was very much affected by (what I observed to be) flag angle changing two to three ranges across. And I soon learned that there was a pattern in a flag beginning to jump to a new position a few seconds before it actually rested in that new position.

Shooting in Pairs or Threes

Shooting in pairs or threes certainly demands experience and good short-term memory.

You need firstly to guess the weather. Shoot to confirm your guess, then adjust on your guess for the next shot, at the same time considering what the set of flags and mirage looked like, and whether you read the weather correctly or incorrectly for that particular shot. For the start of the shoot, it’s more difficult; toward the middle and end of the shoot, one gets more confident with the short-term memory of the weather condition.

What I “think” while shooting/watching the flag is this: once I’ve established the correct wind strength with sighters, I give that particular flag angle/strength a name; for example, “That’s a 3-minute right flag,” etc. So when it’s your turn to shoot again you have to try and remember which short-term imprinted picture of the flags best suits the next shot.

This to me is fairly close to my own string-shooting method, except you’ve got the whole picture (not having to aim and shoot and miss some of the changes). In Africa, there is normally a lot of mirage that accompanies the wind, and the wind effect on the mirage is normally easy to follow. When the wind blows the mirage slowly, I give the picture the name “Thick Syrup Number X”—the X being the number of minutes required to hit the center. When the wind blows the mirage stronger, then I call the picture “Sugar Water Number X.” I’m sure you know why I give the two variables their descriptive names.

For New Shooters

The one thing I wish I had been given the opportunity to do when I first started to shoot was to move the sights into and out of the wind a minute at a time, deliberately moving toward the outer edges of the target to learn how important bold moves are, especially at long range. New shooters are often afraid to move their sights, thinking, “They’ve been zeroed on the bull. Now leave them.” It’s often tough to get a new shooter to learn quickly the effect of wind from 300, 500, 600 meters to 700, 800, 900 meters.

ALAIN MARION, CANADA WINNER OF THE QUEEN’S PRIZE AT BISLEY (THREE TIMES) MEMBER OF DCRA HALL OF FAME

To begin with, in most cases wind is an overrated factor. It is an easy excuse for bad holding. If you looked at it closely, you would find that your best wind dopers are the same people who win matches when there is no wind. How many people do you know became wind-judging experts when they changed to F-Class? You have to fire good shots so that you get some benefit from them in order to judge the wind for the next one.

Authors: When you first arrive at the range for a match, what do you look at and what do you think about?

AM: What I look at when I get to a match depends on whether I know the range or not. If not, I will study the physical geography of the range to see if a hill, a coulee, or anything else could have an effect on the wind currents.

After that, I watch the wind cycles (sometimes . . . ?), but I try to go into the match without a preconceived idea about what it will do.

Authors: When you are preparing to set your sight for that first sighter, what do you think about in order to make that decision?

AM: I take an educated guess for the correction I use for the first sighter; but for a less experienced shooter, it is a good idea to have a wind chart to get started on.

Authors: When you have the results from your first sighter, what do you think about in order to set your sight for the second sighter?

AM: For the second sighter, if I think the wind is the same, I correct to three-quarters of a minute of perfect wind. If it is inside that, I leave it alone.

One thing I have found that has helped me is to spot one flag that is coming in my direction for wind angle and another one with its tip in line with something (for example, the top of a line of trees or the hills across the river at Connaught), which gives me an indication of the variations in strength.

In very light wind, I pay a lot of attention to mirage.

By the way, if a shooter misses small wind changes more often than he thinks he should, he might benefit by installing a spirit level on his front sight.

Under all types of conditions, I always watch to see where people are hitting on the targets that are in the field of view of my scope. This method is particularly good in the big finals, as you are surrounded by good shooters.

If there is a very big wind change, I start over as if I were shooting my first sighter. It is easier to get yourself to think “this is 12 minutes left wind” than to think “I need to make a 6-minute correction.”

The best words of wisdom I could give a new shooter would be to learn to shoot tight groups and to center them. The rest will follow accordingly.

Additional Words of Wisdom from Alain Marion About Gilmour Boa5

I received a stack of old issues of The Canadian Marksman, and when I finally had an opportunity to look through them, I came across an article written by Gil Boa in 1957.6 Gilmour Boa is the only man in the world to have won both the Queen’s Prize and a World Smallbore Championship, not to mention three Queen’s Medals in Service Rifle, the Governor General’s Prize, as well as several Canadian championships in both smallbore and fullbore. Although the article was written nearly half a century ago, when people had to shoot with .303s as issued except for the back sights, there are parts you could quote in the next edition of your book on wind doping. Here are some of the points that I selected from Gil’s article [plus some the authors of this book thought were worth repeating]:

• Whenever riflemen get together, there are long-winded discussions regarding the relative importance of various factors in marksmanship to success in competition. Among the items usually mentioned are good eyesight, steady nerves, physique, rifle accuracy—a subject in itself—ammunition, wind-judging ability, coaching, weather conditions, diet, training habits, the misfortune of being squadded with a slow shooter, and female competitors in tight pants. In my considered opinion, the most important factor, and the one most commonly overlooked by tyro and expert alike, is the ability to hold, aim correctly, and deliver the shot when the sight picture is perfect.

• It is, of course, impossible to make consistently good scores with a poor rifle. It is even more unlikely that a shooter will achieve satisfactory results, even with the finest rifle on the range, unless he is capable of holding it perfectly steady while he aims and fires the shot.

• Wind judging, at least under conditions normally encountered at Connaught Ranges, is a highly overrated ability. The fact is that if we would leave our sights alone, our scores would frequently improve. If anyone doubts this statement, he has only to refer to his own scorebook and estimate what his scores would be with fewer windage changes.

• As for training habits, it is self-evident that a man who keeps in good condition, takes enough exercise to develop stamina, gets adequate rest, and eats and drinks in moderation will be more likely to endure successfully the rigors of a long program than a soft, self-indulgent person. This factor is demonstrated annually toward the end of the program, when certain individuals begin their celebrations a little too early on winning a place on the Bisley Team.

• Other factors, such as weather conditions, squadding, ammunition, and so forth, are beyond the control of the competitor. In a long aggregate they are practically equal for all.

• Thus we return to the all-important consideration, namely, to hold, aim, and fire the shots with such precision that almost all personal error is eliminated.

WORDS OF WISDOM

SMALLBORE WIND-READING LINDA K MILLER

When the first edition of The Wind Book was published, it was met with great enthusiasm from the shooting community . . . except for one reader who was looking for information about reading the wind for Olympic-style smallbore. It was ironic because I had started in that discipline, but had not specifically included it in the book. The Wind Book is largely a reflection of my journey from 50-meter smallbore to 300- to 900-meter fullbore, written to help shooters new to long-range shooting to get through the learning curve.

With the second edition, I decided to cover a little bit about smallbore wind-reading.

I looked through the details of the first edition, looking for what I needed to add to address the idiosyncrasies of smallbore. Wind basics? They are the same. The thought process? The same. The techniques and tactics? Yes, the same. The underlying skills? The same.

But there are two things that are different about smallbore: one is the type of range and the other is the type of flags.

SMALLBORE RANGES

Olympic-Style 50-meter ranges are usually described as a “bowl” because they have some type of wall on at least three and sometimes all four sides. I like to visualize it like a fish tank, with the ripples bouncing between walls until they are resolved or until a larger force overpowers them.

No matter how you visualize it, it’s important to see the wind as a continuous force that must enter, act, and usually exit the range. (Sometimes the wind doesn’t so much exit the range as it dissipates somewhere in the range.) This gives you a good picture of the overall behavior of the air currents you’re going to be dealing with. You may find it helpful to divide the range into thirds: the band closest to you, the midsection, and the target end of the range. It’s usually easiest to read the mid-section, but the band closest to you has the greatest effect on the bullet.

One of my wake-up calls was during a World Cup where the flags were just crazy. There didn’t seem to be a rhyme or reason with their behavior, at least nothing I could latch on to. They looked like you could read them, but no! During sighters, I’d fire a shot expecting one thing and get something completely different. Finally, I noticed a small round-leaf ground cover right in front of the firing line . . . it was describing the wind conditions accurately and eloquently. I used that little ground-cover for the rest of the match, and it was effective enough to put me on the medal podium.

Once you’ve got a good picture of the overall wind conditions on the range, you assess the particular behavior on your own line of fire. I’ve always found it easiest to be in the middle of the range, or somewhat downwind of center, because you can more easily see what wind is coming to you and more easily predict what will be happening by the time you fire your shot. If you are shooting on a firing point that’s close to where the wind is sweeping into the range, it may not have as much lateral force, but you may have to deal with some vertical displacement. I think the most challenging place on the range is where the wind is exiting . . . you do have the full width of the range to see the wind coming, but you must deal with (sometimes unpredictable) swirling as the wind hits the wall and curls back over that side of the range.

In headwind/tailwind range situations, the most critical thing is usually small variations in wind direction, just as it is in fullbore. If you have right wind correction on and the wind shifts to the other side of center, you suddenly have a double error.

In fact, I can certainly understand why so many fullbore shooters use smallbore for cross-training. Nowadays the range conditions are getting more similar, as fullbore ranges are often surrounded by big berms that cause a similar “bowl” effect on the wind currents.

Everything you learned in smallbore can be transferred to fullbore; indeed, those things can also be transferred to Extreme Long-Range shooting. Reading the terrain, dividing the range into behavior-zones, assessing the characteristics of your particular line of fire . . . all good skills to hone, no matter your shooting discipline.