What’s the stock market going to do this year?

What’s the stock market going to do this year?Only the gauche, the illiterate, the frightened and the pastless destroy money.

—William Faulkner

I can tell you from 30 years of experience that the difference between successful investors and unsuccessful investors is the investor, not the investment.

With the advent of discount and robo-brokers, no-load mutual funds and exchange traded funds that cover all of the major investable asset classes are now widely available to anyone. Since the 1970s and the collapse of fixed commissions in the United States, we truly have witnessed a democratization of investing. All the investments are there and are available to everyone with no barriers to entry, and they are practically free. So, we should all be rich, right? Unfortunately, the only true barrier to successful investing that remains is the investor.

Ludwig Börne, the German writer known for saying “Nothing is permanent but change,” also said, “Getting rid of a delusion makes us wiser than getting hold of a truth.” Let’s look at some possible delusions about what we can and cannot do for ourselves. Before stepping back into the investment world I usually prefer stories from real life. These are about three airline passenger emergencies and how they were handled.

A 747 passenger named Paula Dixon, from Aberdeen, Scotland, suffered a collapsed lung on a 14-hour flight from Hong Kong to London. Death was certain except for the lucky fact that two doctors on-board were able to save her using a coat hanger, a surgical tube, and some brandy as a disinfectant. One doctor remarked, “It was a little unpleasant when we went through the chest wall.”1 Dixon lived to laugh at that comment.

In another incident, a woman on an airplane suddenly stopped breathing. Again, on-board were two physicians. With a ball-point pen, a soda can, and some water, they were able to perform a tracheotomy on her and save her life.

Contrast those happy endings with a recent airline tragedy where a 46-year-old Haitian died while in flight from Port au Prince to New York on an Airbus A300-600. The flight had all the modern medical equipment that is required, including defibrillator and first aid oxygen. But, as the Wall Street Journal affirmed, “The decision on what action to take, especially in the early moments of a crisis, usually falls on the flight attendants.”2

These life-and-death stories made me ask: Would I rather have a full surgical facility on my next flight and two flight attendants to operate it (as in the last example), or nothing on-board but stale peanuts and sodas, and two physicians sitting next to me? It was clear from reading these stories that it was the expertise and ingenuity of the physicians that saved the passengers’ lives, not the equipment—unless you want to call a soda can and a ball-point pen emergency medical equipment.

What does this have to do with successful investing? If we are to believe the investment advice from the popular press, all you need to be successful as an investor is a no-load index fund and an internet connection—the equivalent of medical equipment and a flight attendant. But ask these questions: What if the market suddenly drops 1,000 points? What if you lose your job and have to make some hard decisions about your money? What if you need to get a higher return in your IRA but really don’t know the difference among a stock, an ETF, a mutual fund, and a limited partnership? Or, what if you need to save for your child’s education but don’t know the difference among a 529 Plan, UGMA, Coverdell ESA, annuity, or savings bond? Or worse, what if you are simply scared or don’t know what to do? Again, the difference is people (the physician or advisor), not the equipment (defibrillator or no-load fund).

I want you to hire an advisor, but I don’t want you to hire just any advisor. And I want you to invest, but you must be smart about it. Maybe this story will help. I used to live in Manhattan and work for Merrill Lynch. I picked out a territory between 8th and 14th streets on the east and west sides of Fifth Avenue to prospect—basically the East Village. I discovered in the Cole Criss-Cross phone directory that the residents of that area were wealthy, were college educated, and had few children. I liked the “had few children” part because I figured my future clients wouldn’t be wasting their potential investment money on birthday cakes, braces, bicycles, Brownie uniforms, and Big Wheels. It was a good combination for potential discretionary assets to help launch my investment career.

I pounded the list and became a cold-calling cowboy. Mostly I sold New York municipal bonds to widows. I liked them. They were fun and smart, not particularly rich (it took me a couple years to realize that the money was on the Upper East Side), but good for 10 or 20 bonds, and a good joke, every time I called.

They weren’t all widows. One was a brilliant polio survivor named Flatow who worked for a major drug company. He sort of brought me up in the business. When I would get over-excited about a bond he would bellow, Sheath thy happy dagger, boy. Thus was my introduction to Shakespeare. Whenever I asked him for recommendations on how I might improve he’d say, Sure. Why don’t you take a long walk on a short pier? Or, when I would launch into some long-winded explanation of a too-complex investment he would answer with Allow me to misunderstand you.

In one of my cold-calling marathons (I would often make 100 contacts a day, or until my ear hurt so much I couldn’t hold the phone to it) I discovered another interesting chap named Joel, in Flatow’s neighborhood. He was a musician, artist, and…options trader. He told me that he traded XMI, the Major Market Index. The Major Market Index is like the Dow Jones Industrial Average but with 20 stocks instead of 30. He and his business partner, John, had won the Investor’s Business Daily options contest and were interested in telling me about their business as a way to get referrals from me.

I took the #6 train to Union Square from 59th Street to visit them. We met in a large sun-drenched room, the only furniture in which was a grand piano, which Joel played with great skill. They were charming and intelligent. Joel told me that he had a system. This is how most sophisticated investment conversations start. He could tell daily how the market would close as measured by the XMI. He said that he’d call me each morning to tell me if the market was going to close up or down. If I liked what I heard perhaps I would invest with him. It was like Doyle Lonnegan being set up by Kelly Hooker and Kid Twist, but I hadn’t seen the movie The Sting yet, so I stayed in the game. Joel called for a month, which included about 20 trading days. He was never wrong. I couldn’t believe it. Every day he told me the market would rise or fall, it did just that. I thought it was magic.

By the time Joel asked me if I wanted to introduce him to clients I was throwing names at him. I wanted all of my clients in this, but, no matter how fabulous this strategy was, I was still just 25 and could only get one client to give Joel $10,000. You know the rest of the story. Joel stole it. Joel lost it. Joel got another $1,000,000 out of him and lost that. Actually, it was none of the above. After about a year there was somewhere around $5,000 in the account, so the client just closed the account, took his money, and went away.

I learned there really is no magical way to make money short term in the stock market. Even the number-one options trader in the country could not repeat his success long term.

Besides the folly of trading strategies that are short lived like the XMI options strategy, it’s not a good idea to constantly fiddle with your portfolio by trying to pick the highs and the lows, or micromanaging your holdings. If you have carefully analyzed your portfolio selections based on your age, risk tolerance, financial objectives, investment experience, past track record, financial capabilities, family history, debt levels, and other factors, and have carefully created your asset allocation, then any other decision that you make with your portfolio should match those factors, and not just your notion that the market is too high, this stock is not performing as you expected, and so forth. In other words, don’t make a change in three minutes when it took hours to build your portfolio.

Even after 30 years I am still surprised when a client calls me and says we need to make a change after the market drops 100 or 200 points. As if the hours of research, historical evaluations, calculations of risk tolerance and financial means and objectives did not already account for market drops. Think about it: You don’t sell your house when it drops in value.

The best investors rarely look at their statements but could tell you plus or minus $5,000 what their multimillion-dollar net worth is, whereas the worst investors look at their accounts every day but couldn’t tell you within $50,000 what their net worth is. Do you understand the difference? The best investors focus on what is important, like strategy, net worth, and income, but are insensitive to market fluctuations, bad or good news, or others’ opinions.

Here are questions that you do not need to know specific answers to:

What’s the stock market going to do this year?

What’s the stock market going to do this year?

Are interest rates going up or down?

Are interest rates going up or down?

Who is going to win the election: a Democrat or a Republican?

Who is going to win the election: a Democrat or a Republican?

Here are questions you do need specific answers to:

What is my net worth (assets minus liabilities)?

What is my net worth (assets minus liabilities)?

If my stock portfolio dropped by 20%, what would I do?

If my stock portfolio dropped by 20%, what would I do?

How much time do I have to make this investment work?

How much time do I have to make this investment work?

Am I a conservative, moderate, or aggressive investor?

Am I a conservative, moderate, or aggressive investor?

How much am I saving every month?

How much am I saving every month?

We can’t go back to the lessons of Warren Buffett too many times. On a trip to a Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary factory in Dalian, China, Buffett was asked about his investment strategy. He said, “We don’t go in and out of the markets. I simply look at individual businesses and try to figure out where they’re likely to be in five or 10 or 20 years from now.”3 Likewise, think about yourself as a business.

When I think of Warren Buffett I think of the model of investor temperament. Investor (your) behavior is even more important than your investments. As Marshall Goldsmith, management consultant, said, “It’s easy to know theories. It’s hard to change behavior.”4 A wise investor will make more money on a lousy investment than an inexperienced investor will make on a superior investment. Want proof? There’s lots of it. I’ve seen it in my practice. The clients who always second-guess me and their portfolio, buy and sell on a whim, and outsmart the market lose. Those who do the research, learn the fundamentals, like those presented in this book, and stick with their program usually win.

The wonderful author Pearl S. Buck wrote in The Good Earth, “Now five years is nothing in a man’s life except when he is very young and very old.” Investment programs are much like this. The most important times in an investment program are when you start and when you end. Your beliefs and behaviors, and how you manage yourself in the first five years sets the habits for the future. Wherever you are in life, think now that you are starting afresh.

If you truly believe you can start fresh then it will pay to avoid what professors H. Kent Baker and Victor Ricciardi call “Common Behavioural Biases.”5 They have observed eight biases:6

1. Representativeness, or the fallacy of judging an investment good or bad because of past performance. The most recent example is gold and its collapse. I’ll never forget all the investors I had to talk out of buying gold after it quadrupled in eight years to $1,700 per ounce.

2. Regret, or loss aversion. These investors avoid selling losers, even when they should, because it proves (they believe) that they made a bad decision.

3. Disposition effect, selling stocks whose prices have increased, while keeping stocks that are at a loss. Instead, consider cutting your losses and letting your profits run, as the pros do.

4. Familiarity bias. This is where investors buy what they know and avoid obscure investments. Commodities are a good example. Despite that commodities are a better inflation hedge than stocks, and are a good diversifier, they are universally avoided by average investors because commodities are unfamiliar.

5. Worry. Victor Ricciardi determined that 70% of investors associate stocks with the word “worry,” whereas only 10% of investors associate bonds with worry. This is despite the fact that stocks have significantly outpaced bonds over the long term.

6. Anchoring. A great example of this is the financial meltdown from 2007 to 2009. Most investors were so anchored with the belief that the stock market is dangerous that they missed one of the most profitable recoveries in history.

7. Self-attribution. This is when an investor attributes a successful investment to his own talents, but assigns an uncontrollable force to negative outcomes. This is the bias that day-traders suffer from, leads to overconfidence, and the reason why most of them lose in the end.

8. Trend chasing, when investors chase last year’s performance—this year. These are the ones who only buy Morningstar five-star funds. We saw in Day 4 how that strategy tends to work.

Eight no-gos are a lot to remember, I will admit, but they are important. A hint from Baker and Ricciardi: “[A]ppropriate financial planning policies can play a powerful role in keeping clients committed to a consistent and disciplined course of action and in avoiding such biases.”7 How can we successfully fight these biases?

I know, that sounds harsh, so I will soften it: Give yourself two weeks’ notice.

The fact is we need help, particularly the more complicated and dangerous our lives become. I am not going to pretend that you can do this by yourself. As the British rock band Talk Talk lamented in a popular song: Truth gets harder, there’s no sense in lying / Help me find a way from this maze, I can’t help myself.8 Sorry to say, this is not a self-help book. Surprised? Never have there been more self-help books available and more depressed people. For example, the number of patients diagnosed with depression increases by approximately 20% yearly. Meanwhile the market for self-improvement products and services is $9.8 billion with sales of self-improvement books expected to continue to grow significantly.9

There is no substitute for professional help when dealing with depression and other medical conditions, learning a new skill, or just about anything else you need help with.

The best example may be the daily battle with our belts. There are thousands of weight-loss books; their number seems to grow even faster than our weight. Yet, according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) more than two-thirds of Americans are overweight. The American Council on Exercise wrote, “While there is clearly no magic bullet to successfully losing weight, a new study suggests that health coaches may be the next best thing.”10 They refer to a study funded by the NIH and conducted by The Miriam Hospital’s Weight Control and Diabetes Research Center in Providence, Rhode Island, which showed that overweight participants who worked with a professional health coach lost more weight than those who merely worked with a mentor or peer.11

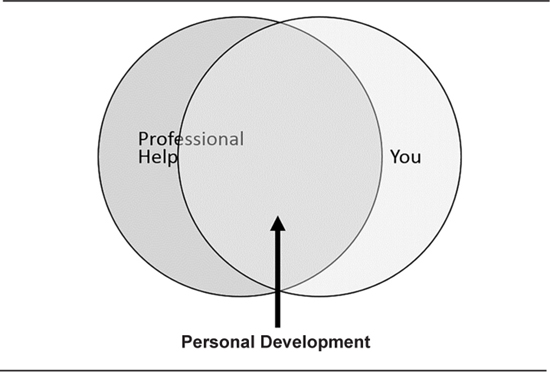

There is no substitute for committed and accountable professional help. I believe that the simple pictures in Figure 5-1 and Figure 5-2 accurately illustrate the advantage of working with professionals over simply reading self-help books.

The message from the self-help industry is that you can do everything by yourself—thus “self-help.” And of course, this is so you will buy more self-help books, tapes, seminars, programs, and so forth. I am not going to consign you to such a dismal and depressing fate in the multifarious and unforgiving investment world. I would rather be honest with you. You need attentive, personal, customized help from a financial advisor. If that is all you get out of this book, then I have accomplished my mission.

John MacDonald, first prime minister of Canada, said, “I need friends with me not when they think I’m right but when they think I’m wrong.” Likewise, the power of an investment adviser is that he or she will help guide you during the tough periods to keep from selling when the market drops and buying too much at the peaks. That is to say that you should consider an adviser who has lived through many financial catastrophes yet stayed true to his or her strategy and performed well.

And regarding the complexity of investing there are now more ways to invest (number of mutual funds) than there are investments (number of stocks). Each way to invest (these new funds) is an attempt to answer the question How should I invest? Therefore let’s ask the question: How should I invest?

We will hear again from James C. Bradford, Jr. Bradford (whom he preferred everyone call Jimmy) was a disarmingly pleasant and unpretentious man and the only Southerner who sat on the board of the NYSE. Perhaps as a reflection of his refinement he told me that he preferred the old term customer’s man to investment advisor because it described better the personal relationship with the client: “He’s working for you. People were to come to you on your reputation. Today it’s a little more adversarial, as NPR says, go get a no-load fund, which is fine, but which no-load fund, or somebody to lead you through the thicket?”12 Again, products are not the key, people are. Just as sick people need doctors, investors need advisors.

Could an advisor help you become wealthier? Writer Lewis Schiff catalogued the seven habits of the ultra-wealthy from his book Business Brilliant.13 Schiff wrote: “Exceptional execution requires those who are business brilliant to focus on the two or three things they do very well. So they get their work done by building teams with complementary capabilities. Surveys show that most people, though, would rather learn to do tasks they’re bad at than get others to do them.” In Schiff’s rankings, “I hire people who are smarter than I am” is number 4. In my rankings this would be number 1.

A professional’s primary objective is to help his or her client do what they are bad at, but particularly to manage expectations. Good doctors do not dilute their prognoses; good lawyers do not misrepresent the strength of your case; accountants do not diminish the possibility of an audit; and good investment advisors do not overestimate the potential in your portfolio.

Be careful with your money. Evaluate the custodian you choose, the investment manager, the clearing firm, the individual securities or funds, the investment advisor, his or her CRD Status Report on FINRA’s “Broker Check,” and the advisor’s employees.

Evaluate everyone—especially you.

Here is what I mean. Though I am not a risk-taker, I did skydive about 30 times years ago. Per incident, it is less risky than scuba diving—that is, diving in the air is less lethal than diving in the water. Remember: I am all about risk; I checked it out first. It is a thrilling sport. It is also quite complex. After you have been involved with it for a while you are expected to buy your own gear (parachute, jumpsuit, altimeter, goggles, helmet, etc.) and pack your own parachute. That’s when I quit. I know me. I am just not very mechanical, and I knew that if I had to pack my own parachute I would forget important details, tie knots into lines that should be left untied, and leave untied lines that should be knotted. I knew that the sport was not safe in my hands, so I quit.

Well, not exactly. In truth, my brother, the owner of the drop zone, threw me out of the sport. Here’s how it happened. One warm summer Saturday afternoon in Tullahoma, Tennessee, I jumped alone out of my brother’s 1956 Cessna 182 at 10,000 feet. Side note: I have always been bad with directions. Not a problem when you are driving around in your car looking for PetSmart in a mall. Definitely a problem when you are falling in the sky at 120 miles per hour and have about three minutes to lock in a safe landing spot 2 miles below. Think of a skydiver as a bullet shot from a gun: Once the gun is aimed and fired the bullet has to continue in the same direction. Skydivers can make slight adjustments with steering toggles by turning left or right, but if you don’t make path corrections at a higher altitude, your landing spot becomes less and less governable.

That’s what happened to me. I sort of daydreamed (one of my dominant traits) for the first 7,000 feet downward, so at a certain point it was too late. I was headed for an active runway. (Hint: Runways are for airplanes; soft and forgiving grass is for skydivers.) As I was descending to the asphalt my problems compounded when an airplane taking off, which could not just stop in mid-air, powered right at me and just barely missed my parachute with its landing gear. The pilot looked right me, astonished, with his mouth wide open in the Wha’ the hell? position.

I was floating at about 200 feet, was scared, and had never seen asphalt growing in my view through my goggles—only grass. It would otherwise not be a big deal to land on asphalt, but it is impossible to “land” when you hit the brakes (by yanking down both toggles simultaneously) at 20 feet—which is what I did. Usually you brake at about 6 feet. At 20 feet I stalled in the air and then free-fell fast at a 45-degree angle to the asphalt, and skidded on my hands and knees in a pathetic and embarrassing runway belly flop. I tore up my brother’s jumpsuit, gloves, altimeter—oh, and my hands and knees.

As I gathered up the parachute and limped back to the drop zone, my brother looked at my bloody knees and hands and his torn-up jumpsuit, and said in disgust, You need your own gear. Then he grounded me.

I have also been interested in being a pilot over the years, an inborn trait in my family. But I also know that all of the prep work—equipment and fuel checks, navigation data, and aerodynamics—would be way beyond my temperament. So I leave the flying to Southwest Airlines.

Why do I mention this? Skydiving and flying are very dangerous if you are not really good at them—like the expression There is no such thing as a pretty good alligator wrestler. If you are no good at skydiving, flying, alligator wrestling, or investing, then, before you have a serious accident, stop doing it yourself.

However, when it comes to the details of accounting, data analysis, finance, economics, money management, asset allocation—the tools of investing—I feel at home. I have a few degrees, lots of licenses and experience, and read and write about investing, and I constantly study. Therefore, managing my clients’ money, and my own money, is something that seems natural to me. The details are not overwhelming or scary.

You need to stop now and ask yourself: Are you more like Andy the skydiver, who can’t be trifled by the details and is therefore the most dangerous flying object in the sky, or Andy the money manager, who is consumed and reasonably skilled? This is a very important question. You need to decide if fundamentally you should be managing your money by yourself, or if you need help.

I am not asking you if you feel lucky, or if you have had a few winners in the stock market. I am asking you if you know that you are competent in investment analysis, bookkeeping, organizing data, reading financial statements, and keeping up with tax law changes; are a student of financial instruments (know the difference, say, between a UIT, ETF, and CMO); and are comfortable with the math of compounding interest, internal rates of return calculations, percentages, probability and statistics, risk measurement, estate planning issues, and the like. If you are not, get out of the cockpit before you crash. Remember: It’s not just you; your family is riding in the back.

When I hear the expression do-it-yourself investor, I think of do-it-yourself parent or do-it-yourself doctor or do-it-yourself electrician. The facts are sobering. Single parents are much likelier to be impoverished than two-parent households: “Among all children living only with their mother, nearly half—or 45%—live below the poverty line, the Census Bureau said.… By comparison, only about 13% of children with both parents present in the household live below the poverty line.”14 I don’t wish to sound callous—sometimes single parenting is thrust upon us—but it should never be a choice.

Do I have to explain why do-it-yourself doctor or do-it-yourself electrician is not a good idea?

Something is not working. The fact is that the average net worth in the United States was $56,000 in 2013.15 Try to retire on that. Face it: We need help.

If you agree to leave the flying to someone more experienced, let’s examine how to choose an advisor and what traits are essential.

First: how not to choose an advisor. I am religious but have always been suspicious of “faith-based” investing. Why? For the same reason that I am suspicious of “socially responsible” investing, and for the same reason that I am suspicious of “affinity” investing—or, in the case of Bernie Madoff, “affinity fraud.” According to the SEC, affinity fraud “refers to investment scams that prey upon members of identifiable groups, such as religious or ethnic communities, the elderly or professional groups.”16 These appellations at times can be a decoy or just a manipulative marketing program. The proper way to evaluate an investment advisor, instead of We worship in the same pews (faith-based investing), or I care more than they do (socially responsible investing), or We’re members of the same country club (affinity investing) is this: You need to evaluate your advisor or money manager in this order:

1. Trust.

2. Competence.

3. Fit.

If the advisor does not pass the trust test, then there is no need to check competence. If he or she does not pass the competence tests, then there is no need to check for fit. Faith-based, socially responsible, and affinity investing start with fit and rarely move backward through the more important steps. Why bother? You are already hooked. As an example, many otherwise-shrewd people invested with Bernie Madoff simply because he was Jewish (faith-based investing); others invested with him because he posed as an elite (affinity investing).

Heed the warning of William Cecil Burleigh: Win hearts and you have all men’s hands and purses. Do not let a prospective advisor or money manager win your heart unless you have first determined if he or she is honest and capable. He or she should win your head first. Start with Finra.org’s “Broker Check.” You can view registered investment advisors, too.

Let’s look closer at Madoff. I was startled by what I learned about Madoff’s firm. “There was no independent custodian involved who could prove the existence of assets,” said Chris Addy, founder of Montreal-based Castle Hall Alternatives, which reviews hedge funds for wealthy clients.17 It is a vital question to know the custodian of your investment accounts and to be able to independently verify your balances. Additionally, Madoff kept the financial statement from the firm under lock and key and was “cryptic” about the firm’s investment business.18 Any reason, so far, to have trust issues with this advisor?

One out of four investors surveyed will write a check without having studied the financial statements of a fund. Nearly one in three will not always run a background check on fund manager. “Due diligence,” says Stephen McMenamin of the Greenwich Roundtable, “is the art of asking good questions.”19 It’s also the art of not taking answers on faith.

After 30-plus years in the business, I have met a few con men. I can tell you that they are the nicest people you will ever encounter. You will feel an instant fit, and forgo the trust and competency review that I recommend. Remember that “con” is short for confidence. They steal your money only after they have stolen your confidence. It is interesting to hear investors talk about them after the scam. Always heard is How could he do that to me? He was such a nice guy. This is not the way the swindler thinks. I believe that most crooks in the investment industry do not mean to steal your money, but only to use it to enrich themselves, and then somehow, they will return your money. It rarely works out like that.

Don’t think that sophisticated investors are immune to swindlers. They are not. The biggest investment theft that I ever was unfortunate to observe happened to the most sophisticated investors I knew.

If your prospective advisor passes the trust test, next is competence. Competence in an investment advisor is the hardest to measure of the three desired traits. The obvious achievements to look for are at least a bachelor’s degree in economics, finance, accounting, math, or some other business discipline; appropriate securities licenses and/or recognized certifications such as CFP, CIMA, CFA, CHFC, CLU, or CPA; and at least three or four years of experience.

Warning: Many investment advisors spend time and money to look appealing (great office, fresh coffee always available, ready smile, pleasant assistants, etc.). You feel like you are with the concierge of a five-star hotel with this advisor. That’s fine—but that is fit, not competency. Again, look for that last. I can’t tell you how many people I know who selected an advisor with the following criteria: He was nice, He had a great office, and My neighbor really likes him. Remember: You’re not looking for a buddy; you are looking for a very important trusted advisor.

Here are some questions you can ask that will quickly get to the competency level of your proposed advisor:

What did the financial crisis of 2008 teach you?

What did the financial crisis of 2008 teach you?

What is your personal expertise?

What is your personal expertise?

What is the biggest loss any of your clients has taken?

What is the biggest loss any of your clients has taken?

What general rate of return would you expect for the long-term moderate-risk-tolerance investor?

What general rate of return would you expect for the long-term moderate-risk-tolerance investor?

What type of investors are not a good fit for your practice?

What type of investors are not a good fit for your practice?

What are the dollar ranges of your accounts—smallest to largest?

What are the dollar ranges of your accounts—smallest to largest?

What would be some ways for each of us to manage expectations?

What would be some ways for each of us to manage expectations?

Which custodian(s) do you use?

Which custodian(s) do you use?

How can I contact them directly and view my account?

How can I contact them directly and view my account?

I am not going to propose specific answers for those questions. I’d rather you take a look at these and see what sorts of “interview” questions you should ask. Finally, don’t listen to your friends’ recommendations unless they assure you that they have checked the three criteria thoroughly.

As I have mentioned, fit is the least important of the three attributes for a suitable advisor for your financial future. But, it is important enough to be one of the three criteria in selecting an advisor. What is fit? Fit, in this case, is a merger of personal styles. If you are an objectives-based, hard-charging, goals-oriented executive, a slow-moving, generalist advisor would be a bad fit. If you value good listeners and all your advisor wants to do is talk over you, this is not a good fit. If you are a “people” person and your potential advisor asks no questions about you, then nothing will change in your professional relationship. Again—bad fit. However, think about your best friend for a minute. If your potential advisor seems like him or her, or has some of the same characteristics, you may be getting close. A good fit will make for a much more pleasurable and productive relationship.

Trust, competency, and then fit. Additionally, you should use these attributes after the hire as well. If you are thinking about firing your advisor simply because lately he or she seems too busy or slightly less enthusiastic about you, stop and ask yourself if your advisor is still trustworthy and competent. Only if he or she fails in those two should you start shopping for a new advisor.

We’ve discussed advisors. Now let’s focus on you. Who are you? You should ask yourself. In all areas of life we should know our strengths and weaknesses. This is especially true when it comes to your money.

When it comes to investing, are you cargo, passenger, or co-pilot? Or, what investor personality type are you? Imagine an airplane. Cargo, like your suitcase, just needs to ride underneath in the storage area. Passengers, however, want to know where they are going, want to plan the trip, and enjoy looking out the window. Co-pilots are that and are also capable of actually flying the plane.

Which are you as an investor? Ask yourself honestly. I have all three types of clients. One is not better than the others. Cargo could not tell you the difference between a stock and a bond. But that doesn’t mean they can’t be excellent investors with the help of a patient advisor. Passengers are competent or at least curious investors, and want to learn more and follow a plan. Co-pilots are experienced able investors, are equipped to invest themselves, but still need help.

Now relate these three investor types back to fit. If your advisor treats you like cargo but you know you are a co-pilot we have a problem. Your objectives, and maybe your ego, will never be satisfied. If he treats you like a co-pilot but you are cargo, you are in for a scary ride. You don’t want to hold the wheel for takeoffs and landings; you just want to get there. I was fired by an important client because I treated them like passengers. They really wanted to be more in control of their investments than I thought they did. I discovered too late that they were co-pilots. It was my fault. Lesson learned. Perhaps it will be easier having this type of “fit” discussion with your advisor if you frame it in these terms instead of trying to decide if your tastes in restaurants, movies, or politics are similar—which is unimportant.

Here’s some encouraging news about working with an advisor. Many studies indicate that investor returns can go up by working with an advisor. Of course there are no guarantees, but the studies are compelling. In a 2007 study conducted by Charles Schwab, participants in retirement plans who did not work with an advisor returned 11.1%, versus 14.1% return for those who worked with an advisor.

Another study evaluated 401(k) plan investors. The study reviewed 14 large retirement plans with more than 723,000 participants. It found that those using help (described as using a target date fund, a managed account, or online advice) now account for 34.4% of all 401(k) participants, up from 30% in 2011. The results? “Between 2006 and 2012, participants in 401(k) plans who paid extra for advice earned an average of 3.32 percentage points more per year, after fees, than those taking do-it-yourself approach. If continued over 20 years, that annual performance edge would boost retirement wealth by 79%,” according to the report.20

After all, 82% of investors with over $150,000 seek advice from financial advisors. This is roughly 15 million households.21 And, the Investment Company Institute found that mutual fund holders with incomes of $100,000 or more are 10 times more likely to have an ongoing relationship with an advisor than those earning less than $35,000.22 It is typically wealthier investors with complex lives who use investment advisers. Perhaps you are one of them, or wish to be.

Do you remember the statistics from Dalbar, Inc. that showed that investors typically underperform the markets? One very important job of an advisor is to keep investors in the markets even during choppy times so they get out of the habit of selling and thereby missing the superior long-term gains that can be earned from being a consistent investor.

The rough composite of the go-it-alone investor looks like this to me: He saw on CNN that no-load funds are better than load funds because they are “free.” He also saw somewhere that stocks are good investments. To complete his education, a friend told him that indexes outperform active managers. So when he adds up the three things that he knows about investing he puts all of his money into an S&P 500 no-load index fund and boasts about his investing prowess. Net result? In the 10-year period through December 31, 2008, he lost money. He gets mad, grumbles about “greed and corruption” on Wall Street, takes his money out of the market altogether, puts everything into a low-yielding money market fund, and retires on far less than he could have had. These are the I used to invest in the stock market but lost money kind of stories that I have heard for years. Rarely do these unfortunate people have advisors.

Retail investors spend most of their investment research time (which is overall less than two hours per year) evaluating funds’ cost, past performance, brand recognition, and what their friends say about the investment; but not more important items like asset classes, management styles, or their own investment objectives. It is no surprise that they are the first to jump overboard when their fund hits a big wave.

Just as a doctor doesn’t just throw drugs at you and disappear, financial advisors attempt to protect investors from the market. I believe that professional money managers are the best protection against market uncertainties, and best poised to take advantage of the market when it goes up. “Among U.S. investors, retirees and investors with $100,000 or more in invested assets are significantly more likely than their counterparts to use a dedicated financial adviser.”23 The same Gallup survey showed that “U.S. investors are more likely to have a dedicated financial adviser than to use a financial website for obtaining advice on investing or planning for their retirement, 44% vs. 20%.”24

Are advisors too expensive? Just as there are expensive five-star hotels and cheap one-star hotels, there is more to advisors than cost. It is the same with any profession. Lawyers are measured by their success in court and relieving clients’ anxieties. When you hire a contractor to lay a wood floor, you don’t complain when hardwood is more expensive than laminate. So why is it that critics pay so much attention to costs and not the effectiveness of the advisor? I cannot guarantee the performance of any fund, but I am reasonably sure that a superior advisor will add value.

Jason Zweig, whom I mentioned previously, wrote: “Of course, much of the value of a financial adviser can’t be captured by measuring the track record of his investment picks alone. By reducing your taxes, planning your estate and retirement, cutting your debt and adjusting your insurance coverage, an adviser can make you much richer and more secure.”25 Perhaps this is why direct sales of mutual funds have dropped in half since 1990 (ICI). Investors seek guidance now more than ever from financial advisors.

Because an advisor will do just about anything for you: keep records, fill out forms, provide second opinions, administer your accounts, income plan, compare complex investments, help with tax and estate issues, protect you from bad ideas, and generally watch over you.

Here are some examples from my own practice over the years. Most of these tasks were done for free and are simply incidental tasks that most advisors perform:

Helped client retrieve cash value from complex insurance policy that was unsuitable. This may have saved client more than $100,000.

Helped client retrieve cash value from complex insurance policy that was unsuitable. This may have saved client more than $100,000.

Helped client retrieve $75,000 in state reclaimed bonds from a major bank. This took hours of work.

Helped client retrieve $75,000 in state reclaimed bonds from a major bank. This took hours of work.

Kept client from dealing with a fraudulent mortgage broker who likely would have absconded with the proceeds of a refinance cash-out. Also alerted the FBI.

Kept client from dealing with a fraudulent mortgage broker who likely would have absconded with the proceeds of a refinance cash-out. Also alerted the FBI.

Notified and corrected a major insurance company that went seven years without properly informing an elderly client that she had required minimum distributions due from her IRA, possibly saving her from tax consequences.

Notified and corrected a major insurance company that went seven years without properly informing an elderly client that she had required minimum distributions due from her IRA, possibly saving her from tax consequences.

Provided records for a client going through a divorce, which proved his premarital assets. This saved thousands of dollars in his settlement.

Provided records for a client going through a divorce, which proved his premarital assets. This saved thousands of dollars in his settlement.

Encouraged client to keep an annuity with only $800 cash value to protect a $10,000 death benefit, which later paid to estate.

Encouraged client to keep an annuity with only $800 cash value to protect a $10,000 death benefit, which later paid to estate.

Put client into a variable annuity in 1993. Then moved to a fixed annuity in December 2001, at peak of stock market and interest rates, thereby locking in gains and providing high income.

Put client into a variable annuity in 1993. Then moved to a fixed annuity in December 2001, at peak of stock market and interest rates, thereby locking in gains and providing high income.

Kept eager client out of stocks in the tech bubble of 1999, saving thousands of dollars. He later sent me a thank-you note.

Kept eager client out of stocks in the tech bubble of 1999, saving thousands of dollars. He later sent me a thank-you note.

Invested client into a variable annuity. Client died in 2004 and death benefit of $10,900 paid out to widow while cash value was only $5,500.

Invested client into a variable annuity. Client died in 2004 and death benefit of $10,900 paid out to widow while cash value was only $5,500.

Joined client at local Social Security office to help him wade through the complex regulations in preparation for his retirement.

Joined client at local Social Security office to help him wade through the complex regulations in preparation for his retirement.

Advised client who was going through marital problems to keep his inheritance separate from his wife. They later divorced and he lost far less money than he would have.

Advised client who was going through marital problems to keep his inheritance separate from his wife. They later divorced and he lost far less money than he would have.

Made multiple clients and prospects aware of the opportunities within their mutual funds to reduce commissions through break-point pricing; and actively search clients’ accounts outside of my firm to reduce commissions.

Made multiple clients and prospects aware of the opportunities within their mutual funds to reduce commissions through break-point pricing; and actively search clients’ accounts outside of my firm to reduce commissions.

Discovered client could rebuy his mutual fund he had earlier sold at net asset value (no commission). He was not aware of this.

Discovered client could rebuy his mutual fund he had earlier sold at net asset value (no commission). He was not aware of this.

Advised client to use appreciated stock instead of cash to make a charitable contribution for $10,000 to save taxes and commission. Tax savings was $520. Then advised him to wait until after the ex-dividend date to transfer to pick up $100 dividend.

Advised client to use appreciated stock instead of cash to make a charitable contribution for $10,000 to save taxes and commission. Tax savings was $520. Then advised him to wait until after the ex-dividend date to transfer to pick up $100 dividend.

Discovered 13 of 23 U.S. savings bonds for client had already come due and were no longer paying interest. She cashed in to reinvest.

Discovered 13 of 23 U.S. savings bonds for client had already come due and were no longer paying interest. She cashed in to reinvest.

Advised client who had quit smoking three years before to call his insurance company to re-rate his policy to non-smoker to save him money.

Advised client who had quit smoking three years before to call his insurance company to re-rate his policy to non-smoker to save him money.

Advised client to wait a day to sell stock to pick up the quarterly dividend of $969. This has happened many times with clients.

Advised client to wait a day to sell stock to pick up the quarterly dividend of $969. This has happened many times with clients.

Expedited annuity application paperwork (at my expense), which earned client 8½% rather than 8% on his fixed DCA (dollar cost averaging) account.

Expedited annuity application paperwork (at my expense), which earned client 8½% rather than 8% on his fixed DCA (dollar cost averaging) account.

Saved client $21,000 from a predatory company that improperly attempted to escheat (transfer to the state) 1,544 book-entry Chevron shares of stock. I needed the help of a lawyer friend for this. Neither he nor I charged the client.

Saved client $21,000 from a predatory company that improperly attempted to escheat (transfer to the state) 1,544 book-entry Chevron shares of stock. I needed the help of a lawyer friend for this. Neither he nor I charged the client.

Saved client 10% excise tax, $1,300, on distribution from her mutual fund IRA by informing her of the permanent disability exception, and provided proper tax forms and IRS documents to back it.

Saved client 10% excise tax, $1,300, on distribution from her mutual fund IRA by informing her of the permanent disability exception, and provided proper tax forms and IRS documents to back it.

Advised client to dollar cost average into the market $1,100,000 10/3/07 when the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) was at 13,968. By March 27, 2008, the DJIA had dropped to 12,303 down 11.92% or 1,665 points but the portfolio was down just 1.68%, saving some $100,000 in potential losses.

Advised client to dollar cost average into the market $1,100,000 10/3/07 when the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) was at 13,968. By March 27, 2008, the DJIA had dropped to 12,303 down 11.92% or 1,665 points but the portfolio was down just 1.68%, saving some $100,000 in potential losses.

Helped a client find lower cost securities bond insurance than the standard 3%, which would save him thousands of dollars for his BP stock.

Helped a client find lower cost securities bond insurance than the standard 3%, which would save him thousands of dollars for his BP stock.

Saved client $420,000 by stopping a fraudulent attempt to wire money out of account.

Saved client $420,000 by stopping a fraudulent attempt to wire money out of account.

After reading all of these, please understand that I am not bragging. Most advisors have scores of stories like these. The media, which is mostly critical and dismissive of investment advisors, will rarely talk about the extras that advisors provide. They want their readers to believe that all advisors care about are fees and commissions. (This also manipulates readers into believing that the media is more valuable than it is.) This is far from the truth. Much of what advisors do for clients has nothing to do with selling them investments and earning a commission.

Instead, industry studies show that the average investment advisor spends most of his or her time on helping you rather than selling you. One such study by Prince and Associates, Inc. and New River found that of the five major advisor activities—1) relationship management, 2) prospecting and selling, 3) portfolio management, 4) professional development, and 5) administrative matters—advisors spend most time on administrative matters.26 Prospecting and selling was number three.

Hire an advisor.