My ventures are not in one bottom trusted, Nor to one place; nor is my whole estate Upon the fortune of this present year.

Therefore my merchandise makes me not sad.

—William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice

After five days (chapters) you may now believe me when I say that stocks are less risky than bonds. But this is only because you know that I mean that balanced against long-term retirement income needs, you have a greater chance of reaching your objectives if you invest in stocks. But you also are a student of the market and know that, just as it did in 2008, the stock market can drop by 37% (the S&P 500, in this case) or more in one year.

So what do you do? What is an actionable way to successful investing? I believe the key is to get odds in your favor. The best way to do that, in my opinion, is to diversify your investments. As venerable money manager Dimensional Fund Advisors says: “Diversification is the most essential tool available to investors. It enables them to capture broad market forces while reducing the excess, uncompensated risk arising in individual stocks.”1 And Nick Murray, prolific speaker and author, gives an interesting definition of diversification: “Diversification is the conscious decision never to be able to make a killing, in return for the priceless blessing of never getting killed.”2 This is the essence of “seeking lower returns” of which I spoke in Day 3.

A wealthy friend told me that diversification is just “five ways to lose money.” He was joking and doesn’t practice this in real life, as he owns property all over the world. He lives in a beautiful modern home in Zurich, owns a penthouse condo in the Four Seasons in Atlanta, and has another spacious home in Franklin, Tennessee. In addition he owns scores of commercial properties. When he crosses the Atlantic to return home, he does so in a first-class berth on the Queen Mary. How? Diversification is the reason he lives as well as he does.

Mark Cuban, the colorful billionaire and owner of the Dallas Mavericks said in a Wall Street Journal interview that “[d]iversification is for idiots.”3 Cuban owns stocks, options, bonds, MLPs, GNMAs, real estate, a popular television show, multiple businesses, IPOs, and of course an NBA basketball team. See the irony yet?

What is diversification? The basic model for diversification is two investments rather than just one investment. It is easy to visualize two investments in which one goes up while the other one goes down. Got it? You are now diversified. Diversification in the securities world was essentially invented by Walter L. Morgan (1898–1998), a CPA in Pennsylvania, in 1928. Morgan managed an active accounting practice and believed the idea of forming a mutual fund would help his clients to invest in a portfolio of stocks and not be burdened by clipping coupons from multiple bonds.

The fund was called Industrial and Power Securities Company and was later renamed the Wellington Fund in 1935, for the Duke of Wellington. The objectives of the fund were: 1) conservation of capital, 2) reasonable current income, and 3) profits without undue risk. The balanced fund of stocks, bonds, and cash helped investors navigate through the most turbulent period in market history. (See Figure 6-1.)

There could not have been a worse time to start a stock mutual fund, or perhaps a better time to start a balanced fund. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) peaked at 381.17 on September 3, 1929, and lost 90% of its value over the next three years to reach a low of 41.22 on July 8, 1932. In contrast, the Wellington Fund lost 58.5%. The DJIA finally closed again above its previous high at 382.74 on November 23, 1954. The Wellington Fund earned a 5.9% annual return during this fateful 25-year period.

In 1974 the Vanguard Group was formed by John Bogle; the Wellington Fund became a charter member. In 1977 the Wellington Management Company board permanently adopted the approximate 65% U.S. stocks/35% U.S. bonds. There were only eight other mutual funds in existence in 1929; today the Vanguard Wellington Fund Investor Shares is by far the largest and most successful of those original funds. I believe that what Morgan created—this “balanced” fund with a fixed combination of stocks and bonds—is the most durable investment strategy ever built. He is my hero, and incidentally gave John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard, his start.

How has the original diversification model done more recently? Figure 6-2 may surprise you. The original diversification model outperformed the first S&P 500 Index fund. For the entirety of the life of the S&P 500 Index fund (inception date August 31, 1976), the balanced (two assets) fund outpaced the one-asset fund, and did so with less risk. And, for all of those whose answer to every investment question is “lower cost,” note that the balanced fund expense ratio is more than 50% higher than the stock fund expense ratio. None of these returns are guaranteed into the future, but I want you to see a very real example of the potential benefits of diversification on the most basic level.

In 1929 the securities markets recognized two asset classes: stocks and bonds. Since then, through securitization, we are able to invest in the worlds’ oldest investable assets (real estate and commodities) using stocks, mutual funds, ETFs, and other means. When you add cash, or money market funds, you see that there are actually then five major investable asset classes: stocks, bonds, cash, real estate, and commodities. As Maurice Sendak said, “There must be more to life than having everything.” With investing everything is stocks, bonds, cash, real estate, and commodities.

You need all of them in your portfolio: stocks for long-term capital appreciation, bonds for income, real estate for more income and growth, commodities as an inflation hedge, and cash to absorb the effects of market movements. I call this moving from black and white diversification (stocks and bonds) to color diversification. Since 2008 I have calculated the total value of all major investable assets.

You can see in Figure 6-3 that the first person to $240 trillion wins, as this is the total value of all investable assets.

Note that commodities and real estate make up almost 30% of the value of total investable assets. As such they are not “alternative investments,” as many investment professionals call them, but are essential portfolio components. In fact, in the 20 years ended 2014, commodities and real estate were likelier than U.S. stocks and bonds to be the top one or two asset classes. These returns, of course, are not guaranteed to continue, as each of these asset classes swap leadership over time, but you would have missed something valuable if you did not own them.

Remember in Day 3 when I talked about the relative advantage of not losing 4% rather than making 4%, and how that magically can give you a higher return? Can diversification help us reduce those negative returns without significantly reducing the positive returns? Yes. Figure 6-4 shows a comparison of the five assets (stocks, bonds, cash, real estate, and commodities), only now expanded to seven assets by dividing stocks and bonds into U.S. and non–U.S. Now we have U.S. and non–U.S. stocks, U.S. and non U.S.–bonds, cash, real estate, and commodities. How have they compared against 100% U.S. stocks, and 60% U.S. stocks/40% U.S. bonds (the traditional balanced model) since 1970?6

Notice that the returns were roughly similar but the standard deviation (a measure of variation of returns, or volatility) dropped dramatically as you moved from one asset (S&P 500), to two assets (60/40), to seven assets. Why does this matter? It matters because, even though you would have made more money in stocks at the very end of this 45-year period, 70% of the time the seven-asset portfolio was worth more than the 100% stock portfolio. This is a potential key benefit of diversification.

As you know, I do not believe that risk equals reward. There are many ways to manage risk: tactically move assets around based on a technical or fundamental preference (such as we will buy stocks when the P/E multiple is below the historic average), move to 100% cash when certain momentum indicators are triggered, hedge using options or futures, and so forth. My way (which thousands of advisors, investors, and I learned from my business partner Craig Israelsen) is to equally weigh multiple low-correlated assets. The seven assets represent this basic strategy. There may be no best way to manage investment risk, but I believe that this is one of the best ways to automatically manage investment risks.

Here’s a way to understand how this works. Figure 6-5 shown on page 193 shows a vexing chart that I have shown my clients for years. Most of them look at me quizzically and wonder quite how this is possible.

Note that both portfolios have an average return of 7%. (This illustration is not dependent on earning 7%, nor is the 7% guaranteed in either portfolio.) The point is that even if you earn the same average return with the diversified portfolio that you earn with the single-asset portfolio, you have the greater chance of making more money in the diversified portfolio with five different investments than the single-asset portfolio. You could end up with investments that underperformed the 7%, too—which is why there is no guarantee that this will work in every market condition.

To be clear, does diversification guarantee greater returns or lower losses? No. There are periods in the market where single assets like U.S. stocks, gold, high-tech stocks, emerging markets, and so forth, go on a run, and the diversified investor looks like a stamp collector quietly admiring his portfolio under a magnifying glass and losing out on all the action.

Alternatively, the market can drop and a diversified portfolio seems to just sink with it. The fourth quarter of 2008 is a good example. However, don’t lose heart; diversification may be a key to preserving and growing capital for the long-term investor. Don’t be too worried about getting it exactly right. As Don Phillips of Morningstar, Inc. said about market activity, “Change is constant, but change is not random.”7 This means that there are certain patterns, strategies, and methods to market activity. Diversification is one of those strategies that is likely to work—and remember: This is all about getting odds in your favor.

When the odds are in your favor, you, not the investment, are in control. You can’t control the market but you can control the downside, or at least reduce it. Control what you can control, and forget about the rest. You cannot control the pluses, but you can control the minuses. This is one of the automatic benefits that diversifying can make: You are there when the markets go up, but more protected when they drop because you own many low-correlated investments.

Before I continue with the virtues of diversifying let me give you three harsh reminders of what happens to you when you don’t diversify: Enron, Madoff, and Japan. If you had 100% of your 401(k) in Enron stock, or 100% of your net worth with Bernie Madoff, or 100% of your money in Japan (for the last 25 years), you are in bad shape. But, you need to recognize these as diversification problems, not as inherent weaknesses with investing.

Enron was not a corporate malfeasance problem for investors. Lack of diversification was the problem. Bernie Madoff’s dishonesty was not why investors are now penniless. Lack of diversification was. Japan’s lost decade (actually two decades plus) was not the problem. Lack of diversification was the problem. Japan is only one country. Why would you have all your savings with one country? Are you seeing a pattern?

Most stories about investors ruined in the market are stories about lack of diversification. The Enron story is a classic where the stock went from $90 to $0 in 331 trading days and finally died in 2001. But that’s not the story. According to Dun & Bradstreet, nearly 100,000 businesses fail yearly in the United States.8 Two hundred fifty-seven public companies with $258 billion in assets declared bankruptcy in 2001, the same year that Enron collapsed.9 There are approximately 15,000 publicly traded companies, 9,000 of which are the major public companies listed in The Corporate Directory from Walker’s Research. Therefore approximately 2% of public companies fail every year. This is why you diversify.

For those who had 5% of their portfolios with Enron, Madoff, or Japan, the losses are simply reminders to diversify. For those who wagered 100% on these, let their misfortune serve as a warning to you. (I guess you could have put 33% in Madoff, Enron, and Japan so diversification does not always work!)

Diversify everything. Diversify asset classes (stocks, bonds, commodities, real estate, money markets, etc.), product types (securities, mutual funds, variable annuities, hard assets, etc.), and custodians (banks, brokerage firms, insurance companies, etc.).

When I say to diversify, I mean it. Every sad story in my business starts with “I gave him everything, and then…” or “I put all I had into X and then.…” I know this sounds defeatist, but I agree with Dr. Quincy Krosby, chief market strategist for Prudential Annuities, who said, “I want my portfolio to be covered for whatever may happen. We are not in control of our destiny anymore, so I want to be diversified no matter what kind of market we are in.”10 Next, record all of your holdings on one spreadsheet. On that spreadsheet you should see a variety of 800 numbers, financial institutions, account numbers, advisors, asset types, and so forth. Your advisor should help you with this. Successful country-western singer Willie Nelson went bankrupt in 1990. To pay off the IRS (which he did in three years) he devoted all of his earnings from an album called The IRS Tapes: Who’ll Buy My Memories?11 Nelson said in an article that the key to his comeback was to compile all of his holdings on one page. This better managed the complications and confusion from his vast estate. Since reading that, I have reduced my clients’ holdings to one page for the same reason.

Figure 6-6 (with a nod of thanks to Callan Associates, Inc. for creating this pictorial teaching style, which they call the periodic table of investments) compares the seven assets described previously for 10-year returns through 2014. Each of the seven assets is ranked in order from top to bottom the highest to lowest annual returns.

The first lesson is that the top-performing asset class is usually not the same every year. The second lesson is that the chart stops with the last full year of returns (in this case 2014). What does that tell you? It tells me that those who compiled the chart did not know what the numbers would be for the following year and beyond. Therefore, what is obvious is that the best-performing assets classes are variable and you cannot predict the future. As an investor, how should you use this information?

First, invest in multiple asset classes for the opportunity to hold the best performers, and so you will not hold only the worst-performing asset. Think of it this way: If you hold 20% each of these five major asset classes (stocks, bonds, cash, real estate, and commodities) you are guaranteed to not have 80% of your assets in the worst category.

The second is that if you do not know the future, what better way to invest than to equally weight?

Here is an example. Let’s assume that you were so excited about U.S. stocks after a return of 33% in 1997 (not shown in Figure 6-6) that you invested 100% of your money into U.S. stocks. In 1998 stocks were up 29%. So far, so good. In 1999 stocks again were up 21%. You are still looking pretty smart, and have decided market timing works when you are as talented as you. Then, to your shock, for the next three years U.S. stocks returned –9%, –12%, and –22% respectively. Your $10,000 investment is now worth $9,710 after five years with 100% in U.S. stocks.

What if, instead of investing 100% in U.S. stocks, you decided to diversify at the end of 1997? You divide your $10,000 into the seven assets in Figure 6-6. Your returns from 1998 through 2002 would have been roughly 4%, 12%, 11%, –6%, and 4%. Your $10,000 would have grown to $12,640 after five years.13 (See Figure 6-7.)

Or, what if you chose “Non–U.S. Stocks” as your sole investment after the 31.8% return in 2009 (shown in Figure 6-6)? If you invested 100% at the end of 2009 into “Non–U.S. Stocks,” five years later you would have been up 32.6% overall, and lost money in 2011 and 2014. Had you instead equally weighted the seven assets you would have been up 36.9% and never lost money in the five year period.14

There are many scenarios in which the numbers would not work out like this, but I believe that you have a better chance of improving your risk-adjusted returns by diversifying than by attempting to pick next year’s winners from last year’s list. But, even if you do not improve your current returns, you may reduce your risk, and I think by now you realize how important it is to reduce risk.

Equally weighting your investments is a suggested model. But be advised, as Thomas Wilson, chief insurance risk officer of ING Group remarked, “A model is always wrong, but not useless.”15 In other words, there are always better ways to choose how to invest after the fact. However, I have found that when you use a model and are broadly diversified, you don’t have to think much about the market, may experience less volatility, and therefore will not be as emotionally or financially at risk.

Figure 6-8 shows the best one-picture illustration of the benefits of diversification that I have seen in more than 30 years in the investment industry. It is from an article written by Eleanor Laise in the Wall Street Journal on January 16, 2008 that illustrates the research of Craig Israelsen, PhD, who was then a professor at Brigham Young University.16 As you can see, the investor starts with large and small U.S. stocks, then adds in equal weights foreign stocks, U.S. bonds, cash, REITs (real estate investment trusts), and commodities. Also assumed are 5% withdrawals, which increase by 3% per year.

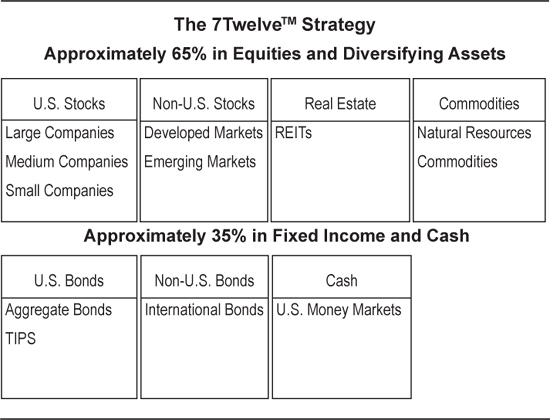

Over the 37-year time period you can see that the returns were stable, but the real story is the dramatic drop in the standard deviation and the worst year’s decline in value as you added assets. Standard deviation (volatility) fell by half, and the worst year’s decline in value dropped by almost 70%. This is significant risk reduction. An investment advisor’s job is either to increase returns or reduce risk. This seemed to be a way to do it. I e-mailed Craig Israelsen that day to introduce myself, and we later built a company off of his 7Twelve™ strategy. The 7Twelve strategy has become one of the most popular investment strategies in the country, with thousands of advisors and investors eagerly using it. This is why it changed my life.

To fully implement this strategy you can see in Figure 6-9 the 7 assets and how they are sub-divided into twelve assets or funds underneath—7Twelve.

I recommend that when you think in terms of an investment model that you consider this as a start. This model is balanced for durability, indexed for cost effectiveness and accountability, passively (or strategically) managed so you do not have to tinker with it, equally weighted, so you do not have to try to predict the market, and diversified into all major asset classes. Think b-i-p-e-d—two feet. This is one way to put two solid and steady feet under your portfolio.

Back-testing, index to index, this 12-asset balanced model has generally shown outperformance of the two-asset model (60% U.S. stocks/40% U.S. bonds) for long periods, though there is no guarantee that this will continue. To be clear: This is not investment advice—only a template. The key is for you and your advisor to find the right mix of investments for your risk tolerances and investment objectives.

What about diversification inside the asset classes? I am surprised to see how much some people invest in single stocks when diversification is so easy. You see this often in retirement plans in which the company match is paid in stock or in stock option plans. It’s not so bad to receive stock as a match if you monitor and sell it occasionally to make sure that you are not over-weighted in the stock. As a rule of thumb, you are over-weighted in any stock that the loss of which would make a significant difference in your life.

Another way to diversify is within mutual funds and variable annuities. Both cost more than owning individual stocks (unless you are holding your stocks in a fee-based account); however, the higher cost can give you:

1. Exposure to more than just a few stocks.

2. Professional management.

3. Automatic tax lot accounting.

4. Customer service.

5. Automatic investing and distribution options.

6. The ability to make lower cost switches between investments and investment strategies.

David L. Martin, an expert in bank mergers and acquisitions, and former managing director of Sandler O’Neill, told me, “I’ll tell you the one thing you need to know about investing, it will fit on one page, never buy individual stocks.”18 I do not think I could build a better case than that for mutual funds.

If you are opposed to mutual funds for some reason or enjoy making your own stock selections you can create a diversified portfolio with individual stock selections as long as you select enough and over a broad range of industries. According to Daniel J. Burnside, PhD, CFA, “As a rule of thumb, diversifiable risk will be reduced by the following amounts.”19

Holding 25 stocks reduces diversifiable risk by about 80%.

Holding 25 stocks reduces diversifiable risk by about 80%.

Holding 100 stocks reduces diversifiable risk by about 90%.

Holding 100 stocks reduces diversifiable risk by about 90%.

Holding 400 stocks reduces diversifiable risk by about 95%.

Holding 400 stocks reduces diversifiable risk by about 95%.

You can control capital gains with stocks easier than you can with mutual funds. Mutual funds have to declare capital gains and pay them out; stocks do not. As you can see there are advantages to both. The choice depends on your personal situation. This is another reason why you need an advisor to help make the right decision for you.

I have spent a lot of time illustrating the difference in returns between stocks and bonds. Because of this you may believe that I am against bonds. In truth, bonds are vital to your well-being and are an excellent diversifier in a portfolio. Remember that they were 40% of the two-asset portfolio that beat the S&P 500 since 1976 that I recently mentioned.

Part of the reason why I have spent so much time on stocks is because you already buy bonds (or certificate of deposit, money markets, etc.) and don’t need me to sell you on them: “The U.S. bond markets total about $40 trillion, twice the size of the approximately $19 trillion U.S. stock market.”20

To attempt to cleverly describe the difference between stocks and bonds, I would like to introduce you to Richard P. Woltman. Woltman is a founder of the independent broker-dealer industry. His broker-dealers were acquired by SunAmerica (later AIG Financial Advisors) and RCS Capital. There is probably no individual in the independent broker-dealer industry that has had a bigger influence than Richard Woltman. Mr. Woltman said, “The investment business is a lot like art. There are many ways to express yourself.”21 I appreciate his sentiment, as it adds verve to an otherwise mechanical industry.

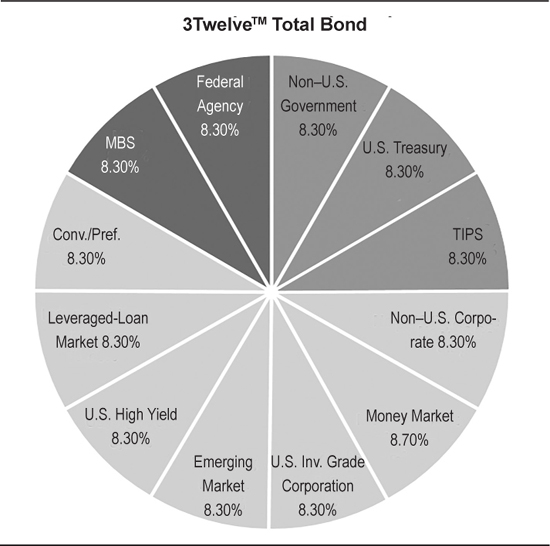

Similarly, some say that stocks are an art, and bonds are a science. Bonds have par values, maturity dates, fixed coupon (interest) rates, senior claims on assets, and inherent guarantees. Some are even insured. Bonds are a science because their price movements can be predicted more accurately than stocks. And frankly, you need some science in your portfolio. Therefore, I created what I believe is the first fully diversified equally weighted bond portfolio called the 3Twelve™ Total Bond. The 3 is for the types of bonds (represented by the medium gray shades in Figure 6-10): government, corporate, and mortgage). The Twelve sub-divides these into equally weighted categories. It is a happy coincidence, but only a coincidence that like 7Twelve (created by Craig Israelsen) there are 12 major categories.

Figure 6-10 shows what the 3TwelveTM Total Bond looks like in one picture.

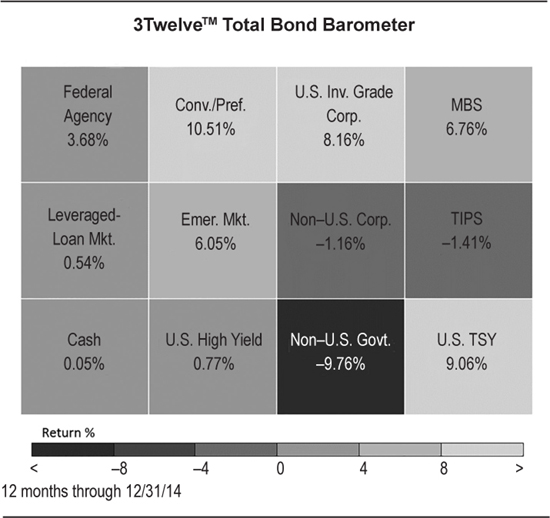

Figure 6-11 illustrates why 3Twelve tends to work. Note the significant dispersion of returns among the 12 bond types22 from a low of –9.76% to a high of 10.51% in the chart. This gives the portfolio a low correlation, which means that you have a well-diversified portfolio instead of 12 bond classes that act similarly. The correlation was less than .40 for the 10-year period ending 2014. Correlation of 1.00 is perfect positive correlation and a correlation of –1.00 is perfect negative correlation. Therefore, .40 suggests low correlation, which is the key to diversification.23

What problem does 3Twelve attempt to solve? A big fear for bond investors is buying a 20-year long-term bond, say, with a fixed interest rate (called a coupon) and then, suddenly, experiencing an interest rate rise. When this happens the same bond that this investor bought is now available with a higher coupon, so his or her bond is instantly worth less money in the secondary market.

However, if instead, the investor put his or her money into the three-asset core (equally weighted), it would have outperformed U.S. Treasury bonds in each of the five periods from 1980 to 1999 that interest rates increased by more than 2%. For the rising rate periods from 1998 to 1999, and from 2003 to 2006, the 3TwelveTM Total Bond outperformed Treasury bonds and other standard bond benchmarks.24

Even investment professionals are surprised to learn that diversification works just as well for bonds as it does for stocks. A full discussion of either the 7Twelve or 3Twelve investment strategies are beyond the scope of this book, but I wanted to give you an introduction to a broader and deeper concept of diversification than you have likely seen. And again, I must remind you that both of these are only models. My message is not Use these models; my message is Find the right model with your advisor—but do find a model.

Here is another way to get the odds in your favor. Princeton University Professor Burton Malkiel found that the S&P 500 beat 70% of all equity managers retained by pension plans over the 1975–1994 20-year periods. Another study by Robert Kirby, former chairman of Capital Guardian, indicated that out of 115 U.S. equity mutual funds that were in business for 30 years or more, only 41 (36%) beat the S&P 500 index, and only 23 of the funds (20%) beat the index by 1% per year or more. Seventy-four of the funds (64%) failed to produce a record equal to the S&P 500’s 10.25% return since 1961. And, using information from CDA/Cadence, Tweedy, Browne Company, LLC found that over the December 31, 1981–December 31, 1994, 13-year period, the S&P 500 beat 81% of the surviving equity mutual funds.25

Finally, Standard & Poor’s was even more definitive when they reported, “The only consistent data point we have observed over a five-year horizon is that a majority of active equity and bond managers in most categories lag comparable benchmark indices.”26 However, during the five-year period ended 2008, the average large value and large blend stock fund beat the passive S&P 500 index.27 That is, in a bad market active management outperformed passive management, so I would caution you against being so doctrinaire that you only invest in indexes.

Indexing is a way to get the odds in your favor—that is, unless it’s not. Aren’t these contradictory opinions? No—not if you diversify. You never know when active management is going to outperform passive management or vice versa, therefore just as you need stocks, bonds, cash, real estate, and commodities, you also need active and passive management in your portfolio. Once again, if in doubt always use the more diversified approach.

As we approach the end, I’d like to share a few more important notes. First, past performance is no guarantee of future return. You see this expression a lot in the investment business. Most of the investment returns figures in this book came from the U.S. markets in the 20th century. The 20th century was a great century for the American stock market. The Dow began at 66.61 in 1900 (January 3, 1900) and ended the century (December 29, 2000) at 10,787.99. The appreciation alone was 6.8% average annual return. The average dividend rate compounded at about 4%, which would yield a total return of more than 10% yearly. This is significantly higher than bonds and inflation. I would challenge anyone to find a higher returning “passive” investment.

What about non–U.S. markets? “Take Japan, please,” to paraphrase Henny Youngman. What a disaster Japan is. None of what I have said in this book is true for Japan. Japan is a socialist, centrally planned, command economy. What’s unsettling about this is that Japan is the world’s third-largest economy by GDP according to the International Monetary Fund.28 It was second largest in 2008. Growth and socialism are bitter opponents. The Nikkei’s (Japan’s benchmark index) all time high was 38,915.87, where it closed on December 29, 1989. It is now, 20-plus years later, trading at less than half of that level. It may be the world’s only equity market that needs a reverse split. It is a 25-year-old story and startles me every time I think about it. Japan is a resounding unmistakable demand to diversify. In November 2008, I asked Bill Spitz, former manager of the endowment for Vanderbilt University, whom I introduced earlier, when will Japan’s equity markets recover? His answer was the most definitive of any answer that any money manager has ever given. He replied, “Never. Japan is incapable of reform.”29

It’s a shame. We were so obsessed with the end of the millennia, which was really nothing more than a numerological oddity, and the hokum of Y2K, that we missed the bigger story, which was the end of the century. The end of the millennia was a geological event, but the end of the century was a generational event: The setting moon eclipsed the setting sun. Author Harold Evans called the 20th century—more specifically the period between 1889 (the settling of the frontier) and 1989 (the inauguration of George Bush)—“The American Century.”

I mention these facts about the power of the U.S. market in the 20th century and Japan’s weakness to suggest that you not make assumptions about the future that do not include that you could be entirely wrong. I want you to be successful even when you are wrong, so diversify.

Also, don’t forget about politicians. They can ruin this. Many in this country are whether they know it or not. Risk-averse former Senator Barney Frank intoned against investing any of Social Security assets in stocks, but became recklessly fearless with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac when he recommend that we “roll the dice” and double down on government’s commitment to these institutions that became the lenders of last resort to millions of insolvent American homeowners. What followed was the worst recession in modern history. So, it’s not that senators are reluctant to gamble, it is that they gamble on the wrong things. After all, these are the people that brought us state lotteries and casinos, both terrible investments, and are much to blame for the permanent poverty class that befalls generations of lower-middle-class Americans.

Or look at the difference between how one president versus another president handled risk. When the space shuttle Challenger exploded in mid-air, President Ronald Reagan described it thus:

I know it’s hard to understand, but sometimes painful things like this happen. It’s all part of the process of exploration and discovery. It’s all part of taking a chance and expanding man’s horizons. The future doesn’t belong to the fainthearted; it belongs to the brave. The Challenger crew was pulling us into the future, and we’ll continue to follow them. I’ve always had great faith in and respect for our space program. And what happened today does nothing to diminish it. We don’t hide our space program. We don’t keep secrets and cover things up. We do it all up front and in public. That’s the way freedom is, and we wouldn’t change it for a minute. We’ll continue our quest in space. There will be more shuttle flights and more shuttle crews and, yes, more volunteers, more civilians, more teachers in space. Nothing ends here; our hopes and our journeys continue.30

Contrast that with President Barack Obama’s handling of the BP Gulf of Mexico oil spill in 2010, starting with his interior secretary Ken Salazar’s threatening, “We will keep our boot on their neck until the job gets done.”31 Obama’s remarks included:

Already, this oil spill is the worst environmental disaster America has ever faced.… Tomorrow, I will meet with the chairman of BP and inform him that he is to set aside whatever resources are required to compensate the workers and business owners who have been harmed as a result of his company’s recklessness.… Already, I’ve issued a six-month moratorium on deep water drilling.32

This incident was just the beginning of a political retreat from oil exploration, and it was perilous for jobs and the economy. One president assured the country that risk is a part of life and we need to press on. Another warned us that some risks are too great and that we should cower from them. When investors cower by moving everything into money market funds and CDs after the stock market drops 20%, they do the same thing. Their unwillingness to accept and to manage risk is actually a greater risk than pressing on. Though it is true that risk does not equal reward, understanding and managing risks, instead of running from them, can bring great rewards. And, as we have seen, risks are functions of opportunities, not just the worst that can happen.

However, let’s not overestimate the rewards, either. I am not trying to sell you 20th-century returns in the 21st century. My theory is that the stock market will only outperform bonds, not that it will produce a 10% long-term annual rate of return. If bond rates stay at 2%, then stocks can double bonds’ returns with a mere 4% return. Even if stocks return their historical premium over stocks, which is about 3–4%, we are still just talking about 5–6% returns in stocks. Is their precedent for such a dreary outlook? Yes. Back to Japan. In Japan, interest rates have dropped and stayed low, the population is aging with no sign of a turnaround, savings rates have dropped accordingly, and the stock market has responded as expected.

These myriad problems are best handled not by making bold predictions but by diversifying. Diversification is the shield against nearly everything that is attacking your future.

I hope that I have built the case that:

1. Risk reward.

2. Stocks are less risky than bonds long term.

4. Predict yourself, not the stock market.

5. Hire an advisor.

6. Diversify.

If you agree with what you have read here then take this book to your existing advisor and ask him or her to apply it to your portfolio. If you do not have an advisor now, you have enough of a personal investment philosophy and sufficient motivation to ask the right questions to hire the right advisor. Whichever is the case, please start now. “Touch has a memory,” wrote John Keats. The longer you wait, the greater your chance of forgetting some of these themes and back you will be to where you were. Intentional investors win; the rest depend on luck. And remember: Bad luck (not good luck) is embedded into the market because the math is against you. To win you need to act differently.

Caution: This book, alone, is not investment advice. I am not saying that I am not an investment advisor. I am saying that I cannot give you proper investment advice anonymously through a book such as this. Nor is this book legal or tax advice. I have many friends who are lawyers and accountants, but that doesn’t make me one. Before implementing any of these strategies, please consult with a professional credentialed investment advisor.

All returns herein are estimates and not guaranteed. Additionally, past performance does not guarantee future returns. I don’t say this to protect myself or to hedge; I say this because it is true. Finally, there is no guarantee that using the investments and techniques described herein will yield a positive result for you. The investment markets are now and will always be an open system with no boundaries. Because there are infinite factors that determine securities prices, predictions about returns and outcomes are impossible.

I am confident that if you have thought carefully about these concepts and work to apply them in your investing life that your outcomes will improve. I wish for you nothing but good fortune.