Chapter 4

Come On In, the Water’s Fine! Water-Bath Canning

IN THIS CHAPTER

Discovering water-bath canning

Discovering water-bath canning

Recognizing high-acid foods

Recognizing high-acid foods

Stepping up to high-altitude canning

Stepping up to high-altitude canning

Knowing the proper processing procedures

Knowing the proper processing procedures

With water-bath canning, you essentially use a special kettle to boil filled jars for a certain amount of time. Common foods for water-bath canning include fruits and tomatoes, as well as jams, jellies, marmalades, chutneys, relishes, pickled vegetables, and other condiments.

You’re probably wondering whether water-bath canning is safe for canning food at home. Rest assured: The answer is a most definite “Yes!” — provided that you follow the instructions and guidelines for safe canning.

In this chapter, you discover which foods are safely processed in a water-bath canner and step-by-step instructions for completing the canning process. In no time, you’ll be turning out sparkling jars full of homemade delicacies to dazzle and satisfy your family and friends.

Water-Bath Canning in a Nutshell

Water-bath canning, sometimes referred to as the boiling-water method, is the simplest and easiest method for preserving high-acid food, primarily fruit, tomatoes, and pickled vegetables.

To water-bath can, you place your prepared jars in a water-bath canner, a kettle especially designed for this canning method (see the section, “Key equipment for water-bath canning,” for more on the canner and other necessary equipment). You then bring the water to a boil and maintain that boil for a certain number of minutes, determined by the type of food and the size of the jar. Keeping the water boiling in your jar-filled kettle throughout the processing period maintains a water temperature of 212 degrees. This constant temperature is critical for destroying mold, yeast, enzymes, and bacteria that occur in high-acid foods.

Foods you can safely water-bath can

You can safely water-bath can only high-acid foods — those with a pH factor (the measure of acidity) of 4.6 or lower. So just what is a high-acid food? Either of the following.

- Foods that are naturally high in acid: These foods include most fruits.

Low-acid foods that you add acid to, thus converting them into a high-acid food. Pickled vegetables fall into this category, making them safe for water-bath canning.

You may change the acid level in low-acid foods by adding an acid, such as vinegar, lemon juice, or citric acid, a white powder extracted from the juice of acidic fruits such as lemons, limes, or pineapples. Some examples of altered low-acid foods are pickles made from cucumbers, relish made from zucchini or summer squash, and green beans flavored with dill. Today, tomatoes tend to fall into this category. They can be water-bath canned, but for safety’s sake, you add a form of acid to them.

Key equipment for water-bath canning

Just as you wouldn’t alter the ingredients in a recipe or skip a step in the canning process, you don’t want to use the wrong equipment when you’re home-canning. This equipment allows you to handle and process your filled jars safely.

The equipment for water-bath canning is less expensive than the equipment for pressure canning (check out Chapter 9 to see what equipment pressure canning requires). Water-bath canning kettles cost anywhere from $25 to $45. You may want to purchase a “starter kit” for about $50 to $60, which includes the canning kettle, the jar rack, a jar lifter, a wide-mouth funnel, and jars.

Following is a list of the equipment you must have on hand, no exceptions or substitutions, for safe and successful water-bath canning.

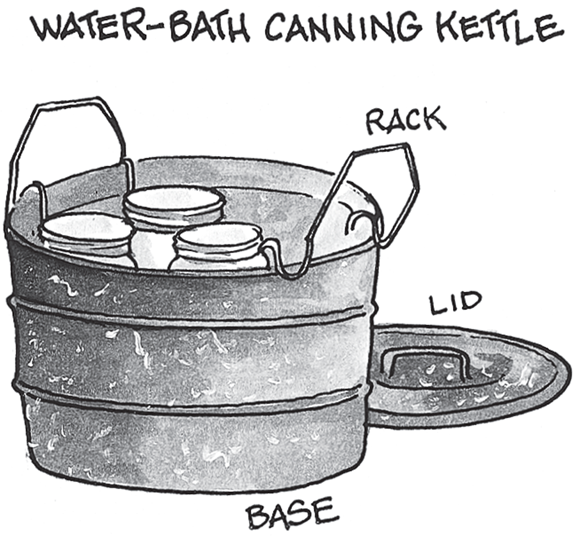

A water-bath canner: The water-bath canner consists of a large kettle, usually made of porcelain-coated steel or aluminum, that holds a maximum of 21 to 22 quarts of water, has a fitted lid, and uses a rack (see the next item) to hold the jars (see Figure 4-1). Do not substitute a large stock pot for a water-bath canner. It is important for the jars to be sitting off the bottom of the canner, and racks that fit this purpose are included in your canner kit.

Although aluminum is a reactive metal (a metal that transfers flavor to food coming in direct contact with it), it’s permitted for a water-bath canner because your sealed jar protects the food from directly touching the aluminum.

Although aluminum is a reactive metal (a metal that transfers flavor to food coming in direct contact with it), it’s permitted for a water-bath canner because your sealed jar protects the food from directly touching the aluminum.- A jar rack: The jar rack for a water-bath canner is usually made of stainless steel and rests on the bottom of your canning kettle. It keeps your jars from touching the bottom of the kettle, or each other, while holding the filled jars upright during the water-bath processing period. The rack has lifting handles for hanging it on the inside edge of your canning kettle (refer to Figure 4-1), allowing you to safely transfer your filled jars into and out of your kettle.

FIGURE 4-1: A water-bath canning kettle with the rack hanging on the edge of the kettle.

- Canning jars: Canning jars are the only jars recommended for home-canning. Use the jar size recommended in your recipe. For more on canning jars, refer to Chapter 2.

Two-piece caps (lids and screw bands): These lids and screw bands, explained in detail in Chapter 2, create a vacuum seal after the water-bath processing period, preserving the contents of the jar for use at a later time. This seal protects your food from the reentry of microorganisms.

The older-style rubber rings are no longer recommended. Although they are sometimes still available secondhand, the seal is no longer dependable enough to result in a safe product. You can find these rubber rings in some specialty canning stores; however, due to their scarcity, they are very expensive and sold in small quantities. Reserve this type of canning jar and kitschy design for your fun food gifts, not canning for a family’s pantry.

The older-style rubber rings are no longer recommended. Although they are sometimes still available secondhand, the seal is no longer dependable enough to result in a safe product. You can find these rubber rings in some specialty canning stores; however, due to their scarcity, they are very expensive and sold in small quantities. Reserve this type of canning jar and kitschy design for your fun food gifts, not canning for a family’s pantry.

- A teakettle or saucepan filled with boiling water to use as a reserve.

- A ladle and wide-mouth funnel to make transferring food into your jars easier. The funnel also keeps the rims of the jars clean, for a better seal.

- A lid wand so that you can transfer your lids from the hot water to the jars without touching them.

- A jar lifter so that you can safely and easily lift canning jars in and out of your canning kettle.

- A thin plastic or wooden spatula to use for releasing air bubbles in the jar.

The Road to Your Finished Product

Every aspect of the canning procedure is important, so don’t skip anything, no matter how trivial it seems. When your food and canning techniques are in perfect harmony and balance, you’ll have a safely processed product for use at a later time.

The following sections guide you through the step-by-step process for creating delicious, high-quality, homemade treats for your family and friends.

Step 1: Getting your equipment ready

The first thing you do when canning is to inspect your equipment and get everything ready so that when you’re done preparing the food (Step 2 in the canning process), you can fill your jars immediately.

Inspect your jars, lids, and screw bands

Always review the manufacturer’s instructions for readying your jars, lids, and screw bands. Then inspect your jars, lids, and screw bands for any defects as follows.

- Jars: Check the jar edges for any nicks, chips, or cracks in the glass, discarding any jars with these defects. If you’re reusing jars, clean any stains or food residue from them and then recheck them for any defects.

Screw bands: Make sure the bands aren’t warped, corroded, or rusted. Test the roundness of the band by screwing it onto a jar. If it tightens down smoothly without resistance, it’s useable. Discard any bands that are defective or out of round (bent or not completely round).

You can reuse screw bands over and over, as long as they’re in good condition. And because you remove them after your jars have cooled, you don’t need as many bands as jars. A good rule of thumb is to have as many bands as you will need to run your canner, full, in a day. Keep in mind that your finished jars will need time to cool before removing the bands to be reused. I prefer keeping at least three canner loads of bands so that I always have enough extra.

You can reuse screw bands over and over, as long as they’re in good condition. And because you remove them after your jars have cooled, you don’t need as many bands as jars. A good rule of thumb is to have as many bands as you will need to run your canner, full, in a day. Keep in mind that your finished jars will need time to cool before removing the bands to be reused. I prefer keeping at least three canner loads of bands so that I always have enough extra.- Lids: All lids must be checked before using each year. Single-use lids aren’t reusable. Check the sealant on the underside of each lid for evenness. Don’t use scratched or dented lids. Defective lids won’t produce a vacuum seal. Don’t buy old lids from secondhand stores. Older lids will not seal properly. Reusable lids must be checked for nicks and cracks. The rubber gaskets should be inspected for decay or breakage.

Wash your jars, lids, and screw bands

After examining the jars for nicks or chips, the screw bands for proper fit and corrosion, and the new lids for imperfections and scratches, wash everything in warm, soapy water, rinsing the items well and removing any soap residue. Discard any damaged or imperfect items.

Get the kettle water warming

Fill your canning kettle one-half to two-thirds full of water and begin heating the water to simmering. Remember that the water level will rise considerably as you add the filled jars. Be sure to not overfill at this point.

Keeping your equipment and jars hot while you wait to fill them

While you’re waiting to fill your jars, submerge the jars and lids in hot, not boiling, water, and keep your screw bands clean and handy as follows.

- Jars: Submerge them in hot water in your kettle for a minimum of 10 minutes. Keep them there until you’re ready to fill them.

- Lids: Wash single-use lids in hot, soapy water, then dry and set aside until needed. Sterilize reusable lids and gaskets in simmering water until you’re ready to use them.

- Screw bands: These don’t need to be kept hot, but they do need to be clean. Place them where you’ll be filling your jars.

Step 2: Readying your food

Always use food of the highest quality when you’re canning. If you settle for less than the best, your final product won’t have the quality you’re looking for. Carefully sort through your food, discarding any bruised pieces or pieces you wouldn’t eat in their raw state.

Follow the instructions in your recipe for preparing your food, like removing the skin or peel or cutting it into pieces.

Similarly, prepare your food exactly as instructed in your recipe. Don’t make any adjustments in ingredients or quantities of ingredients. Any alteration may change the acidity of the product, requiring pressure canning (see Chapter 9) instead of water-bath canning to kill microorganisms.

Step 3: Filling your jars

Add your prepared food (cooked or raw) and hot liquid to your prepared jars as soon as they’re ready. Follow these steps:

Transfer your prepared food into the hot jars, adding hot liquid or syrup if your recipe calls for it, and being sure to leave the proper headspace.

Use a wide-mouth funnel and a ladle to quickly fill your jars. You’ll eliminate a lot of spilling and have less to clean from your jar rims. It also helps cleanup and prevents slipping if you place your jars on a clean kitchen towel before filling.

Release any air bubbles with a nonmetallic spatula or a tool to free air bubbles. Add more prepared food or liquid to the jar after releasing the air bubbles to maintain the recommended headspace.

Before applying the two-piece caps, always release air bubbles and leave the headspace specified in your recipe. These steps are critical for creating a vacuum seal and preserving your food.

Before applying the two-piece caps, always release air bubbles and leave the headspace specified in your recipe. These steps are critical for creating a vacuum seal and preserving your food.Wipe the jar rims with a clean, damp cloth.

If there’s one speck of food on the jar rim, the sealant on the lid edge won’t make contact with the jar rim and your jar won’t seal.

Place a hot lid onto each jar rim, sealant side touching the jar rim, and hand-tighten the screw band.

Don’t overtighten because air needs to escape during the sealing process.

Step 4: Processing your filled jars

With your jars filled, you’re ready to begin processing. Follow these steps:

- Place the jar rack in your canning kettle, suspending it with the handles on the inside edge of the kettle.

Place the filled jars in the jar rack, making sure they’re standing upright and not touching each other.

Although the size of your kettle seems large, don’t be tempted to pack your canner with jars. Only place as many jars as will comfortably fit yet still allow water to move freely between them. And always process jars in a single layer in the jar rack.

If your recipe calls for the same processing times for half-pint and pint jars, you may process those two sizes together. Otherwise, don’t process half-pint or pint jars with quart jars because the larger amount of food in quart jars requires a longer processing time to kill any bacteria and microorganisms.

If your recipe calls for the same processing times for half-pint and pint jars, you may process those two sizes together. Otherwise, don’t process half-pint or pint jars with quart jars because the larger amount of food in quart jars requires a longer processing time to kill any bacteria and microorganisms.Unhook the jar rack from the edge of the kettle, carefully lowering it into the hot water, and add water if necessary.

Air bubbles coming from the jars are normal. If your jars aren’t covered by 1 to 2 inches of water, add boiling water from your reserve teakettle or saucepan to achieve this level. Be careful to pour this hot water between the jars, instead of directly on top of them, to prevent splashing yourself with hot water.

Air bubbles coming from the jars are normal. If your jars aren’t covered by 1 to 2 inches of water, add boiling water from your reserve teakettle or saucepan to achieve this level. Be careful to pour this hot water between the jars, instead of directly on top of them, to prevent splashing yourself with hot water.Cover the kettle and heat the water to a full, rolling boil, reducing the heat and maintaining a gentle, rolling boil for the amount of time indicated in the recipe.

Start your processing time after the water boils. Maintain a boil for the entire processing period.

If you live at an altitude above 1,000 feet above sea level, you need to adjust your processing time. Check out “Adjusting Your Processing Times at High Altitudes” later in this chapter for details.

Step 5: Removing your filled jars and testing the seals

After you complete the processing time, immediately remove your jars from the boiling water with a jar lifter and place them on clean, dry kitchen or paper towels away from drafts, with 1 or 2 inches of space between the jars.

If you are using single-use lids, don’t attempt to adjust the bands or check the seals — simply step away and allow them to cool completely. If you are using reusable lids, allow the jars to cool for 5 to 10 minutes and then tighten the bands securely, using a clean dish towel to protect your hands from the hot metal and glass. The cooling period may take 12 to 24 hours.

After your jars have completely cooled, test your seals on the single-use lids by pushing on the center of the lid (see Figure 4-2). If the lid feels solid and doesn’t indent, you have a successful vacuum seal — congratulations! If the lid depresses in the center and makes a popping noise when you apply pressure, the jar isn’t sealed. Immediately refrigerate unsealed jars, using the contents within two weeks or as stated in your recipe. (See the nearby sidebar, “Reprocessing unsealed jars,” for do-over advice.)

FIGURE 4-2: Testing your jar seal.

Test a reusable lid by removing the metal band from the cooled jar and slightly lifting the jar off the work surface, holding on to just the lid. A properly sealed jar can be lifted by the lid. An unsealed jar — you guessed it — will allow you to lift that lid right back off again.

Step 6: Storing your canned food

After you’ve tested the seal and know that it’s good (see the preceding section), it’s time to store your canned food. To do that, follow these steps:

- Remove the screw bands from your sealed jars.

Wash the sealed jars and the screw bands in hot, soapy water.

This removes any residue from the jars and screw bands.

- Label your filled jars, including the date processed.

- Store your jars, without the screw bands, in a cool, dark, dry place.

Adjusting Your Processing Times at High Altitudes

When you’re canning at an altitude higher than 1,000 feet above sea level, you need to adjust your processing time (see Table 4-1). Because the air is thinner at higher altitudes, water boils below 212 degrees. As a result, you need to process your food for a longer period of time to kill any microorganisms that can make your food unsafe.

TABLE 4-1 High-Altitude Processing Times for Water-Bath Canning

Altitude (in feet) |

For Processing Times Less Than 20 Minutes |

For Processing Times Greater Than 20 Minutes |

|---|---|---|

1,001–1,999 |

Add 1 minute |

Add 2 minutes |

2,000–2,999 |

Add 2 minutes |

Add 4 minutes |

3,000–3,999 |

Add 3 minutes |

Add 6 minutes |

4,000–4,999 |

Add 4 minutes |

Add 8 minutes |

5,000–5,999 |

Add 5 minutes |

Add 10 minutes |

6,000–6,999 |

Add 6 minutes |

Add 12 minutes |

7,000–7,999 |

Add 7 minutes |

Add 14 minutes |

8,000–8,999 |

Add 8 minutes |

Add 16 minutes |

9,000–9,999 |

Add 9 minutes |

Add 18 minutes |

Over 10,000 |

Add 10 minutes |

Add 20 minutes |

If you live higher than 1,000 feet above sea level, follow these guidelines.

- For processing times of less than 20 minutes: Add 1 additional minute for each additional 1,000 feet of altitude.

- For processing times of more than 20 minutes: Add 2 additional minutes for each 1,000 feet of altitude.

In addition to the must-have items listed here, you may also want the following items. These aren’t critical to the outcome of your product, but you’ll discover a more streamlined, efficient level of work if you use them (you can find out more about these and other helpful-but-not-necessary tools in

In addition to the must-have items listed here, you may also want the following items. These aren’t critical to the outcome of your product, but you’ll discover a more streamlined, efficient level of work if you use them (you can find out more about these and other helpful-but-not-necessary tools in