THE “NEW PEOPLE”

PORCELAIN PUNCH BOWL DEPICTING SWEDISH SHIP, BROUGHT BACK FROM CANTON ON THE EMPRESS OF CHINA BY THE SHIP’S CARPENTER, JOHN MORGAN.

IN THE FACE OF LIGHT RAIN, “FRESH BREEZES AND A TUMBLING swell,” the Empress of China, accompanied by the French ship the Triton, sailed up the Pearl River estuary on August 23, 1784, and into China’s realm. Six months after leaving New York, having traversed about eighteen thousand miles of ocean, the Americans had triumphantly arrived. After the Empress of China anchored in the Macao Roads, Captain Green ordered a seven-gun salute, which was returned by the fort on Macao, just three miles away. Then Samuel Shaw, the ship’s supercargo, and John Swift, its purser, unfurled the Stars and Stripes and hoisted it aloft. This was the first time the American flag had flown in this part of the world, and it was a thrilling sight for all the men onboard. But Shaw took only a few moments to relax and reflect on their achievement. Captain Green had succeeded in getting the Empress of China to its destination. Now it was Shaw’s turn to take the helm of this venture.1

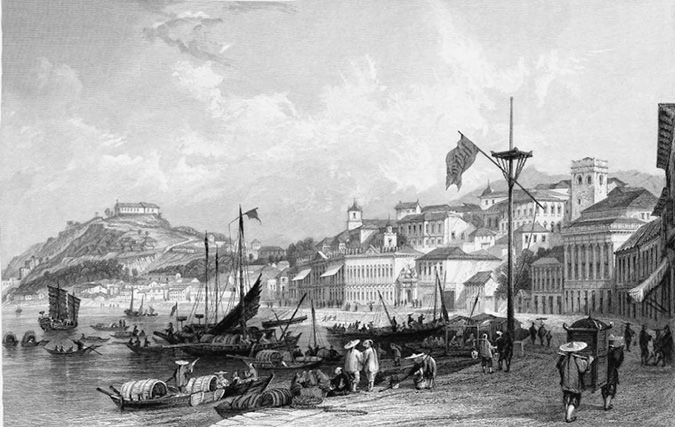

The next day Shaw and others from the ship visited the Portuguese outpost of Macao, paying their respects at the governor’s residence, stopping by the customhouse to get a chop, and dining with the French and Swedish consuls. Although Macao had, as Anson observed some forty years earlier, “fallen from its ancient splendor,” it was still a striking place. About three miles long, and from a half to one mile wide, Macao had a population of around twenty thousand, about four thousand of whom were Portuguese and their African slaves, with most of the rest being Chinese, along with a smattering of other Europeans. Sandwiched between a harbor on one side and a stunning crescent-shaped beach—Praya Grande—on the other, Macao was a sliver of Europe in the Orient. Its narrow, winding streets were lined with impressive buildings of stone and brick, including a few Catholic churches and the mansions where foreign merchants lived when they weren’t in Canton.2

PRAYA GRANDE, MACAO, BY THOMAS ALLOM, 1843.

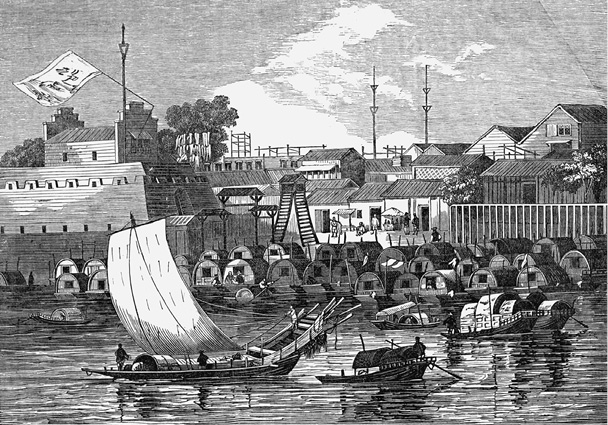

WHAMPOA ANCHORAGE, BY YOUQUA, CIRCA 1845.

With a pilot onboard, the Empress of China left Macao on August 26 and arrived at Whampoa two days later. Most of the thirty-five foreign ships that would trade at Canton that year were already anchored in this relatively narrow and congested stretch of the river. When Green saluted them with thirteen guns, they all responded with resounding salvos of their own, which echoed across the water and the hills beyond. The French, the Danes, the Dutch, and the British sent welcoming parties, and later that day Shaw, Green, and Randall returned the visits. “The behavior of the gentlemen on board the respective ships,” Shaw commented, “was perfectly polite and agreeable. On board the English it was impossible to avoid speaking of the late war. They allowed it to have been a great mistake on the part of their nation,—were happy it was over,—glad to see us in this part of the world,—hoped all prejudices would be laid aside,—and added, that, let England and America be united, they might bid defiance to all the world.”3

Shaw and Randall left Whampoa for Canton on August 30. It is striking indeed that Shaw, the only person onboard who kept a journal while in China, failed to record a single thought about the sights and sounds that greeted the Americans as they traveled from Macao to Canton. In this completely alien land, Shaw must have been amazed by the landscape unfolding around him, but perhaps he was too sober to give voice to his wonder. Fortunately others were not so reticent. A Frenchman who had covered the same ground twenty years earlier began his narrative on the approach to the mouth of the Pearl River. The first thing that arrested his attention was the “forest of masts, and soon after an innumerable multitude of boats, which covered the surface of the water.” Thousands of fishermen, plying their ancient trade, were trolling the depths for the ocean’s bounty. The river itself was also choked with boats, “its banks lined with ships at anchor; [and] a prodigious number of small craft . . . continually gliding along in every direction, some with sails, others with oars, vanishing often suddenly from the sight, as they enter the numberless canals dug with amazing labor, across extensive plains, which they water and fertilize.” Beyond the river’s edge farmers toiled in “immense fields, covered with all the glory of the harvest,” and “stately villages” could be seen in the distance. Mountains, “cut into terraces, . . . shaped into amphitheatres,” and carpeted with the lush, green growth of summer, formed “the background of this noble landscape.” Arriving at Canton, the traveler was greeted by a new and no less dramatic scene. “The noise, the motion, the crowd augments,” as both the water and the land were “covered with multitudes” of people, perhaps as many as a million.4

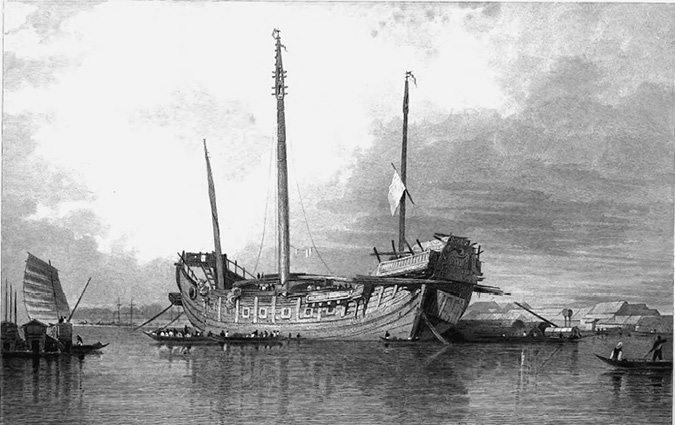

The number of Chinese vessels on the river in the vicinity of Canton ran into the tens of thousands, and ranged in size from five-hundred-ton junks, with fierce eyes painted on their bows, to small sampans used for fishing or ferrying supplies. Ornate flower boats, where prostitutes offered themselves to wealthy Chinese customers, competed for space with much plainer houseboats, on which extended families lived and worked in cramped quarters. Canton might really have been two cities, one terrestrial and the other aquatic, both humming with ceaseless activity.

ON THE PEARL RIVER AT CANTON, 1837.

The Americans, being from a “new country,” didn’t yet have a factory in Canton. So once again their fast friends, the French, lent a helping hand, housing the Americans until September 6, when their own factory, a formerly empty building, was ready. Constructed of granite or brick in an imposing European style, the factories were located about three hundred feet from the river on the edge of a partially stone-paved courtyard called the Square, and each one had a flagpole out front to identify the nationality of the occupants within. The factories were quite large, two or three stories high, with bedrooms, parlors, offices, a dining room, and a veranda above, and a kitchen, servants’ quarters, and storage areas below. Behind the factories ran a broad avenue called Thirteen Factory Street, which was connected to the Square by three much narrower streets or alleys, ranging from just three to fifteen feet wide. Along these crowded and noisy thoroughfares vendors and peddlers hawked their wares from shops and carts, offering a fantastic choice of objects for sale, from silks and China sets to carved ivory and ornamental wood-and-lacquer boxes. A profusion of brightly colored and curiously translated signs vied for the attention of passersby. Establishments called “Collective Justice,” “Peace and Quiet,” and “Perfect Concord” enticed customers with catchy, and often quirky slogans such as “Rich customers are perpetually welcome,” and “Here are sold superior goods, in whose prices there is no change.” A common water tub was labeled “the bucket of superlative peace,” and a chest “the box of great tranquility.”

CHINESE JUNK ON THE PEARL RIVER, 1833.

Foreigners, including crewmen, who were occasionally shuttled up to Canton from Whampoa, passed the time wandering these streets and buying presents to bring home. They also witnessed the incredibly varied Chinese diet. Alongside the chickens and exotic fruits and vegetables were rats, cats, and dogs for sale, the sight of which amused and alarmed the foreigners, who often wondered if there was anything the Chinese wouldn’t eat. The sailors would be sure to make a special visit to Hong Lane—or as it was more appropriately called by the foreigners, Hog Lane—where all types of local liquor could be had for a price, and it was not uncommon to witness brawls or see men sprawled on the street, sleeping off the effects of some potent brew—perhaps a few too many drafts of samshoo, a popular Chinese wine made from fermented rice. Shaw later said that what transpired on Hog Lane “surpasses fable: it is the residence and resort of pick-pockets and knaves of all nations, and always in an uproar with hogs, dogs, &c.”5

SHAW AND RANDALL were invited to dine at other factories on a few occasions, and they reciprocated in kind. They also attended concerts at the Dutch factory, and accompanied other Europeans on trips across the river to eat at the palatial estates owned by the hong merchants. Nevertheless, Shaw’s opinion of social life in Canton was rather bleak. “The gentlemen of the respective factories” kept to themselves, he noted, except for occasional gatherings, and even then the men were “very ceremonious and reserved.” Shaw did not envy the Europeans. “Considering the length of time they reside in this country,” he said, “the restrictions to which they must submit, the great distance they are at from their connections, the want of society, and of almost every amusement, it must be allowed that they dearly earn their money.”

The Chinese had never heard of the United States, and were not quite sure what to make of the Americans, at first thinking that they were Englishmen, since they looked similar and spoke the same language. Once the Chinese were disabused of that notion, however, they dubbed the Americans the “New People” (in later years the Chinese would call the Americans the “Flowery-Flag Devils,” because the stars in a field of blue on the American flag looked to the Chinese like flowers). The more the Chinese learned of the Americans, the more intrigued they became. According to Shaw, when he showed the Chinese a map, and “conveyed to them an idea of the extent of our country, with its present and increasing population, they were not a little pleased at the prospect of so considerable a market for the productions of their own empire.”

FROM SEPTEMBER THROUGH mid-December, as fall gave way to the relatively warm and humid winter for which subtropical Canton was known, Shaw and Randall, with the assistance of their hong merchant, traded for Chinese goods. Alternately impressed and disgusted with the process, Shaw thought that the Canton system was “perhaps as simple as any [commerce] in the known world.” As for honesty, however, it depended on whom you were talking about. “The knavery of the Chinese, particularly those of the trading class, has become proverbial,” Shaw contended:

There is, however, no general rule without exceptions; and though it is allowed that the small dealers, almost universally, are rogues, and require to be narrowly watched, it must at the same time be admitted that the merchants of the Cohong are as respectable a set of men as are commonly found in other parts of the world. It was with them, principally, that we transacted our business. They are intelligent, exact accountants, punctual to their engagements, and, though not the worse for being well looked after, value themselves much upon maintaining a fair character. The concurrent testimony of all the Europeans justifies this remark.6

It is important, however, to place Shaw’s comments in context. “Knavery” or unscrupulous behavior in the merchant class, was not something exclusive to China, and at another point in his narrative Shaw admitted that it occurred elsewhere in the world. If some of the Chinese merchants were in fact any worse than their foreign counterparts, it was only a difference in degree, not kind.

No sooner had Shaw and Randall begun trading than they learned a painful lesson in supply and demand. Prices for goods were not static. Increasing supply inevitably drove prices down, ginseng in this case being the unfortunate example. The Empress of China had arrived with the single largest shipment of ginseng Canton had ever seen. But the Europeans had also brought an enormous amount of the prized root, leading purser Swift to claim, “This year ten times as much arrived as ever did before.” By the time Shaw and Randall sold their ginseng, the price had already fallen precipitously, since many of the Europeans had already sold theirs.7

Despite the disappointing sale of ginseng, Shaw’s disgust with “small dealers,” and his belief that “every servant in the factories . . . [was] a spy,” the trading went well, with only two issues. The first came early on, after the hoppo finished measuring the Empress of China to assess port duties. According to convention, the hoppo asked the foreigners to see the sing-songs or gifts. This posed a problem, since there were none onboard. Shaw apologized, saying that the Americans were “from a new country, for the first time, and did not know that it was customary to bring such things.” The hoppo accepted this explanation but warned them not to make the same mistake on future visits. Despite this lapse in etiquette, the hoppo followed through with another tradition—that of sending foreign ships a present from the emperor, to let them know that the Son of Heaven wished them well. Hours after the hoppo departed the Empress of China, Green accepted delivery of “two bulls, eight bags of flour, and seven jars of country wine.”8

A FAR MORE SERIOUS problem than the absence of sing-songs arose on November 24, just as a dinner party on the Lady Hughes, a British ship anchored at Whampoa, was coming to an end. To salute the guests on their departure, live cannons were fired. One of the blasts inadvertently hit a boat that was “lying alongside” the Lady Hughes, injuring three of the Chinese onboard, one of whom died the next day. The Chinese officials demanded that the gunner who fired the shot be turned over, but the British reported that he had “absconded” and couldn’t be found. The head of the British factory also informed the Chinese that the British East India Company had no authority over the Lady Hughes, since it was a “country ship,” licensed by the company but owned by private British traders who shuttled between India and Canton. If the Chinese wanted answers, they should speak with George Smith, the supercargo of the Lady Hughes.

Three days after the incident Smith received a message saying that his hong merchant wanted to see him on business. Smith left the factory area only to discover that the message was a ruse when sword-wielding soldiers took him into custody. Immediately thereafter all trading was halted, the streets around the factories were blocked and filled with soldiers, and the Chinese merchants, linguists, and compradors evacuated the area. Although the hoppo had forbidden communication between Canton and Whampoa, the supercargoes managed to get word to their ships in Whampoa to send boats with armed men to Canton in order to protect the factories. Four to five hundred men responded and headed upriver.

The “Canton War,” as Shaw dubbed it, had thus begun. The Chinese fired on the approaching force, wounding two men, but all the boats arrived safely. At about the same time the region’s governor sent a message to the foreigners, saying that whether the deaths were by “accident or design,” the gunner needed to be produced and tried according to Chinese law, and that as soon as the gunner stepped forward, Smith would be released. The governor added that the foreigners must comply, and that he would array his forces to keep them from leaving. “Reflect therefore, & see what is your force and your ability,” the governor concluded. “If you dare in our country to disobey & infringe our laws, consider well that you may not repent when it is too late.”

The British, Danish, French, Dutch, and American supercargoes formally protested the taking of Smith, who was clearly innocent, having been in Canton the day of the event. They also defended their sending for armed boats, claiming that it was necessary to protect themselves and their property. The governor responded on the evening of the twenty-eighth, asking the supercargoes of all the countries except Britain to attend a meeting, at which time he told them his quarrel was with the British and not with them. The governor repeated his desire that the gunner be turned over, and also assured the supercargoes that if he was found innocent he would be let go. Although the foreigners had violated Chinese law by bringing armed boats into Canton, the governor said he would excuse this infraction as long as the boats left, which they all did but for the Americans who decided to stay and support the British cause. With that, trade between the Chinese and all the non-British Europeans resumed.

As the armed European boats were departing, Smith wrote a letter to Mr. Williams, the captain of the Lady Hughes, asking him to send the gunner to Canton, which was done on November 30. As soon as the gunner was handed over, Smith was released, and on December 6 the embargo on trade with the British and the Americans was lifted. The next day the Lady Hughes left for India. A little more than a month later, the emperor found the gunner guilty, and he was strangled to death.9

TO THE BRITISH what happened was a clear miscarriage of justice. They felt that the gunner was not guilty of a crime. He had not meant to kill anyone, the deaths were accidental or unintentional, and it was unfair to require “blood for blood” under such extenuating circumstances. Leniency, not a charade of a trial, was what was called for. Holding the British collectively responsible for the gunner’s act, and taking Smith hostage, was viewed as equally unjust. More ominously the British perceived this event as part of a larger pattern. Four years earlier a French sailor and a Portuguese sailor on a British ship anchored in Whampoa got into a fight, leaving the latter dead. Although the British claimed that the Frenchman acted in self-defense, the Chinese demanded that the sailor be turned over and come before a Chinese tribunal. This was done, and a day later the sailor, having been found guilty of murder, was strangled at a location near the factories. In British eyes, therefore, the two cases meant that should another accidental death occur in the future, they would be faced with one of two unpalatable choices: handing over an innocent man to be killed, which would dishonor Britain, or getting out of the Canton trade altogether.10

Shaw’s perspective was in line with that of the British. Writing after the gunner had been turned over but before he had been strangled, Shaw concluded that this “troublesome affair, which commenced in confusion, [and] was carried on without order . . . [had] terminated disgracefully. Had that spirit of union among the Europeans taken place which the rights of humanity demanded, and could private interest have been for a moment sacrificed to the general good, the conclusion of the matter must have been honorable, and probably some additional privileges [regarding the handling of such cases] would have been obtained.”11

The Chinese, in contrast, viewed the situation quite differently. According to the historian Li Chen, who has dug deeply into both the British and the Chinese records, there is “little evidence for the traditional belief that the Lady Hughes case best demonstrated the corruption, arbitrariness, and/or inhumanity of Chinese law and justice.” Chen raises many valid questions, among them that, although it might have been an “accidental homicide,” it could still have been the result of criminal negligence, and therefore liability would have applied. The Chinese boat was clearly alongside the Lady Hughes, within the line of sight for the gunner, and the gunner should not have fired live rounds, since Chinese law forbade the possession or use of firearms in its territory. Furthermore the delays in turning over the gunner were seen as an obstruction of Chinese justice, and given past misbehavior of British and other foreigners on Chinese soil, it was important for the emperor not to be seen as incapable of protecting his own people and enforcing the law.12

Determining who was right or wrong in this situation, or who acted properly, is well beyond the scope of this book. What is critical, though, is how this situation affected the course of history. It was the British view of events that became the standard interpretation in the West. In Britain in particular, the Lady Hughes incident remained an open wound that would fester and dramatically affect future relations not only between China and Britain, but also between China and the United States.

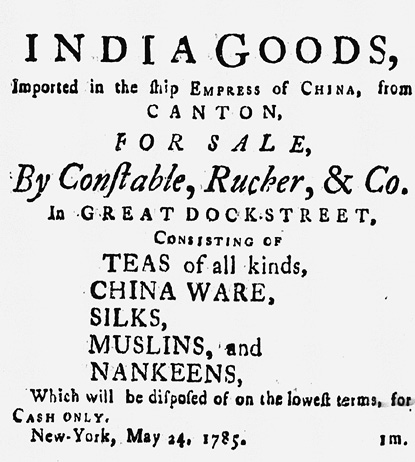

ITS TRADING DONE, the Empress of China set sail for America on December 28, 1784, just a few months before John Adams would become the first U.S. ambassador to Britain. In the ship’s hold were the fruits of Shaw’s and Randall’s efforts in Canton: seven hundred chests of bohea tea, one hundred chests of hyson tea, twenty thousand pairs of nankeen trousers, and a large amount of porcelain. The return voyage was uneventful, the only exception being the death of the ship’s carpenter, John Morgan, who had begun the trip in poor health and expired just after crossing the equator in the Atlantic. At noon on May 11, 1785, after a fifteen-month absence, and having sailed, according to the ship’s log, a total of 32,458 miles, the Empress of China anchored in New York’s East River and once again saluted the city with thirteen guns.13

NEWSPAPER ADVERTISEMENT ANNOUNCING THE SALE OF ITEMS FROM THE EMPRESS OF CHINA.

Soon after docking, Shaw, justifiably proud of the Empress of China’s accomplishment, submitted a report to John Jay, the minister for foreign affairs, intended “for the information of the fathers of the country.” Shaw recounted the strict trading protocols of the Canton System, said that his Chinese and European hosts had treated him and his men well, and concluded with a hopeful thought: “To every lover of his country, as well as those more immediately concerned in its commerce, it must be a pleasing reflection, that a communication is thus happily opened between us and the eastern extremity of the globe.” Jay responded by telling Shaw that the members of Congress felt “a peculiar satisfaction in the successful issue of this first effort of the citizens of America to establish a direct trade with China, which does so much honor to its undertakers and conductors.”14 One of those members, the Virginian William Grayson, shared his sense of “satisfaction” with James Madison (then a member of the Virginia House of Delegates), writing in late May 1785:

I imagine you have heard of the arrival of an American vessel at this place in four months from Canton in China, laden with the commodities of that country. It seems our countrymen were treated with as much respect as the subjects of any nation, i. e., the whole are looked upon by the Chinese as Barbarians, and they have too much Asiatic hauteur to descend to any discrimination [Grayson used the term more in the sense of “loftiness” that that of outright arrogance]. Most of the American merchants here are of the opinion that this commerce can be carried on, on better terms from America than Europe, and that we may be able not only to supply our own wants but to smuggle a very considerable quantity to the West Indies. I could heartily wish to see the merchants of our state engage in the business.15

Thomas Jefferson, America’s minister to France, took the opportunity of the Empress of China’s return to send the French foreign minister, Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes, a report on the ship’s momentous maiden voyage, which also served as a thank-you to the French for their kind treatment of the Americans: “The circumstance which induces Congress to direct this communication,” noted Jefferson, “is the very friendly conduct of the consul of his Majesty at Macao, and of the commanders and other officers of the French vessels, in those seas. It has been with singular satisfaction, that Congress have seen these added to the many other proofs of the cordiality of this nation towards our citizens.”16

The Empress of China earned its backers $30,727, for a return of a little more than 25 percent on their original investment—not nearly as much as they had hoped, but enough to make the voyage a financial success.17 Newspapers announced the ship’s return, and its cargo radiated outward from New York City to be sold in stores up and down the coast. One paper reported that since the ship “brought such articles as we generally import from Europe, a correspondent observes that it presages a future happy period of our being able to dispense with the burdensome and unnecessary traffic which heretofore we have carried on with Europe, to the great prejudice of our rising empire, and future happy prospects of solid greatness: And that whether or not the ship’s cargo be productive of those advantages to the owners, which their merits for the undertaking deserve, he conceives it will promote the welfare of the United States in general, by inspiring their citizens with emulation to equal, if not exceed, their mercantile rivals.” Just above this pronouncement, as if to highlight the significant break with the past symbolized by the Empress of China, there was a notice of a new book just published in London, titled, “The Prospect of a Reunion Between Great Britain and America, by an American Officer.”18 But such a reunion was not to be. America was getting back on its feet after the Revolution, and heading in new and profitable directions—the Empress of China’s voyage was proof of that.

Less than a month after the Empress of China docked, a British gentleman residing in New York City wrote a letter to a friend back home, reflecting on the venture. “Among the many novelties which daily flow from the copious sources of fortune, none more singular . . . has presented itself here, than the arrival of the ship the Empress of China,” which had succeeded in bringing back the “golden fleece” in the form of Chinese goods. “This voyage . . . is an immense thing, and opens a vast resource to the United States.” But at the same time the correspondent realized that this success posed a serious threat to the European, and in particular the British, trade with China. “It strikes me as an event that should open the eyes of my native country to the real situation of this rising empire . . . as the great rival to Europe. . . . It has now opened the gates of the East, and the first beams of their morning have promised a splendid meridian to their commercial day.”19

This gentleman’s prescient musings eloquently captured the hope embodied in the Empress of China’s triumphant voyage. He wasn’t the only one who saw in the ship’s return the prospect for the dawning of a new “commercial day,” in which America would bid fair to compete with Britain, and all of Europe, for the riches of the East. As word of the Empress of China’s successful trip spread, a growing number of American merchants headed out to get their piece of the proverbial China pie.