“THE ADVENTUROUS

PURSUITS OF COMMERCE”

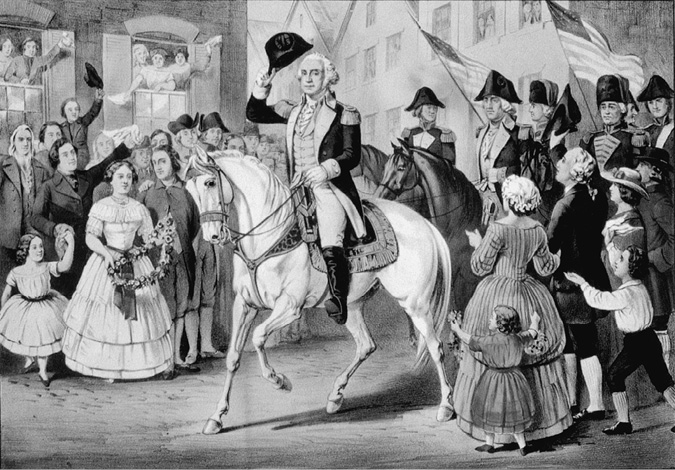

GEORGE WASHINGTON’S ENTRY INTO NEW YORK ON THE DAY THE BRITISH EVACUATED THE CITY, NOVEMBER 25, 1783, CURRIER & IVES, 1857.

SOON AFTER THE TREATY OF PARIS WAS SIGNED ON SEPTEMBER 3, 1783, officially ending the American Revolution, the former colonies were hit by one of the worst winters in recent memory. From Maine to Virginia the temperature plummeted in mid-November, and for the remainder of the year the region was battered by a string of powerful storms, some dumping nearly two feet of snow. Ice, at first appearing as a thin glaze at the edges of harbors and riverbanks, spread, swallowing open water at a quickening pace. Two brief but intense thaws in January melted the snow and set ice floes in motion, but at the end of the month winter clamped down again and there was nothing John Green could do except wait. As captain of the Empress of China, Green had wanted to sail out of New York in early February, but ice in the East River and the harbor beyond barred his way. The situation worsened as the mercury dipped below zero for days on end. Finally the temperature rebounded, causing the ice to retreat, and on Sunday, February 22, as the sun rose in the brilliant blue sky and gentle winds rippled the surface of water, it was time to get under way. The Empress of China cleared the wharf, and Green and his forty-two-man crew began their groundbreaking voyage, thus launching America’s trade with China.1

At the same time another ship, the Edward, also headed down the East River, bound for London with the “Public dispatches of Congress, for the respective courts, containing the definitive articles of peace.”2 The coincidental sailing of these two ships provides a historical juxtaposition that could have been conjured by a novelist. While the Edward was delivering what could arguably be called the birth certificate of the United States, proclaiming the arrival of the newest nation, the Empress of China was making a very important statement of its own, announcing to the world that this new nation was ready to compete in the international arena. The symbolism didn’t end there. Even the date of departure provided its own dramatic flourish, for February 22 was George Washington’s fifty-second birthday. Although that, too, was just a coincidence, it was particularly fitting that the infant nation’s first foray to the Far East should have commenced on the birthday of the man who had done more to found the United States than any other person. Washington couldn’t have asked for a better omen than the departure of these two ships, which embodied the hope for America’s future.

The Empress of China’s voyage was borne on the twin pillars of necessity and opportunity. With the signing of the Treaty of Paris, one trial had ended and another had begun. America had broken free of the constrictive political and economic bonds of Great Britain, and the Americans who had fought so long and hard for this day basked in the warm afterglow of freedom and possibility. They were subjects no more. A toast raised in Charleston, South Carolina, on July 4, 1783, after the preliminary articles of peace had been ratified by the Continental Congress, captured the jubilant mood of the country: “To this glorious day, by which we secured, among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station, to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle us.”3 At the same time, however, this freedom came at a terrible cost. The nation was mired in an economic depression, much of its commerce hobbled, its central government in disarray, and the states were squabbling with one another over their powers and responsibilities. Given all this, it was not uncommon for Americans to wonder how their country would make its way in the world.

Many enterprising merchants, who had profited handsomely during the war and still had ships and resources at their disposal, believed that the answer lay overseas, but with whom would they trade? The Revolution had severed the formal union between the colonies and Great Britain, and cast asunder the long-standing mercantile connections between the two. The British government, viewing the United States as a potentially dangerous competitor, cut off virtually all American trade with the British West Indies, which had been one of the main arteries of colonial commerce prior to the Revolution. At the same time it was becoming clear that America was going to face trade barriers from other European nations intent on protecting their own commercial interests. Confronted with this increasingly hostile landscape, the United States needed not only to establish improved trading relationships with European powers but also develop new ties with other countries in order to ensure its economic future.4 To that end China presented a tantalizing opportunity.

In the decades leading up to the Revolution, Americans had obtained the Chinese goods they desired—including porcelain, silk, tea, and a rough, sturdy cotton fabric called nankeen—from British merchants or from smugglers who brought the goods to America’s shores. One thing that the Americans couldn’t do, however, was trade directly with China. The only entity in the British Empire allowed to do so was the monopolistic British East India Company, which had been established in 1600. Since America was no longer part of the empire, its merchants were now free to go to China. Leading the way was Robert Morris.

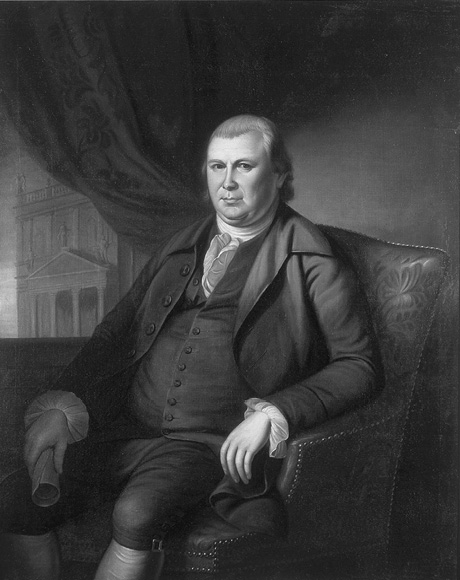

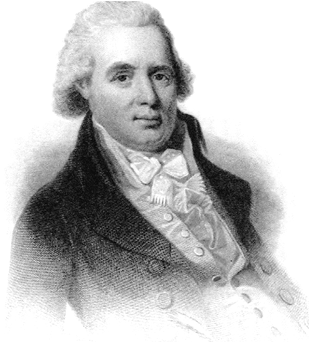

BORN IN LIVERPOOL in 1734, Morris remained in England until the age of thirteen, when he came to America to join his father, a tobacco merchant who had settled Oxford, Maryland, on the eastern shore of Chesapeake Bay. An industrious boy with an inquisitive mind, Morris quickly outgrew the narrow confines of Oxford, and two years after he arrived his father sent him to Philadelphia, already a cosmopolitan metropolis of twenty thousand people, the largest British city on the continent. After a brief tenure as a librarian, Morris began clerking at the shipping firm of Charles Willing. Morris swiftly rose through the ranks and became fast friends with Willing’s eldest son, Thomas, who also worked at the firm and was being groomed to lead it one day.5

ROBERT MORRIS, BY CHARLES WILLSON PEALE, FROM LIFE, 1782.

When Mr. Willing died in 1754, Thomas took over the firm, and installed Morris as his trusted lieutenant, soon elevating him to partner in the firm of Willing, Morris & Company. Willing, whose friends called him “Old Square Toes” on account of his serious demeanor and conservative nature, chose wisely in selecting Morris. Together they built Willing, Morris & Company into one of the premier merchant houses in America. By the early 1770s Morris had married, started his own family, and was firmly ensconced at the pinnacle of Philadelphia society.6

During the Revolution, Morris pursued two paths, one public and the other private. As a delegate to the Continental Congress, he favored negotiating with Britain, and would not sign the Declaration of Independence until August 2, 1776. In so doing he affirmed his unreserved support for the cause, purportedly declaring, “I am not one of those politicians that run testy when my own plans are not adopted. I think it is the duty of a good citizen to follow when he cannot lead.”7 When the Continental Congress needed someone to curtail government spending, reduce public debt, coordinate foreign loans, and breathe life into America’s woefully underfunded war effort, it tapped Morris. As a member of Congress and as superintendent of finance, Morris established the first national bank and did the fiscal equivalent of spinning straw into gold. Time and again Morris drew upon his financial acumen, his connections, his negotiating talent, and his own fortune to pull together money and materials, the twin fuels without which the war could not be waged. At Valley Forge and Yorktown, when George Washington needed infusions of cash and supplies to keep his troops from literally walking off the job and bringing the war effort to a grinding halt, Morris spearheaded the effort to provide these essential items.8

Morris also served as the agent of the marine, to develop what he called “our infant and unfortunate navy.”9 It was a sensible choice. Morris had the requisite background, having been heavily involved in maritime trade before the war through his fleet of merchantmen, and he applied his financial skills to get the bankrupt navy on an even keel.

In and out of government, Morris, “the Financier of the Revolution,” also attended to his private business, for however ardent a patriot he was, he was equally committed to making money. Morris expanded his trading empire, outfitting privateers to plunder British shipping. Although many regarded Morris as a profiteer as a result of his wartime business activities, the latter “elevated him to a position where he was acknowledged as the most prominent merchant in America.”10

As the Revolution wound to a close, Morris began withdrawing from public service and turned more of his attention to his business affairs. One of the investment prospects foremost on his mind was the China trade. In 1780 two of Morris’s business associates, the New Yorker William Duer and the French consul in Philadelphia, John Holker, tried to entice him to fund a trading voyage to China, but Morris declined, arguing that the resources necessary to mount such an expedition were not available. The next year Holker approached Morris again, with the same result.11 But by mid-1783, as peace finally hove into view, Morris was nearly ready. All he needed was the spark provided by John Ledyard.

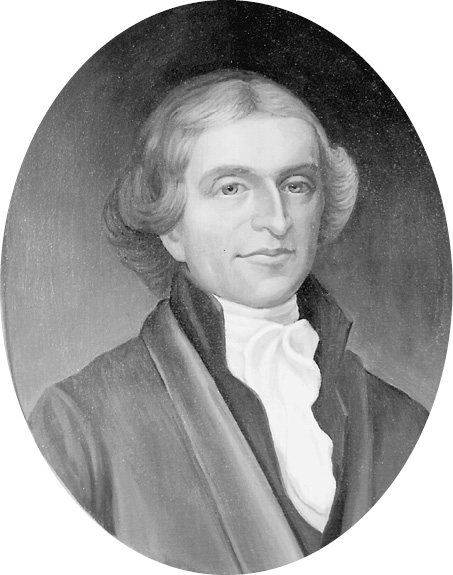

BORN IN GROTON, CONNECTICUT, in 1751, Ledyard had compiled a rather undistinguished résumé by the outbreak of the Revolution, having been expelled from Dartmouth College, followed by stints as a divinity student and as a seaman transporting mules, molasses, flour, and sugar between Africa, Europe, the West Indies, and Connecticut. Perhaps his most notable achievement was carving a canoe out of the trunk of a pine tree and paddling it 140 miles on the Connecticut River, from Hanover, New Hampshire to his parents’ home in Hartford, Connecticut, becoming the first known white person to traverse that stretch of water. In March 1775 Ledyard sailed to England, where he was impressed into or volunteered for the British army, and then within a few weeks managed to get transferred to the navy. Ledyard found his life as a marine based dockside in Plymouth dull and enervating. He was a restless wanderer who needed adventure, which he found on July 5, 1776, when he signed on as a corporal on HMS Resolution, one of two ships that the famed British explorer James Cook was leading to the Pacific Ocean in an attempt to find the fabled Northwest Passage to the Orient.12

PAINTING OF JOHN LEDYARD BY JOSEPH SWAN, 1991.

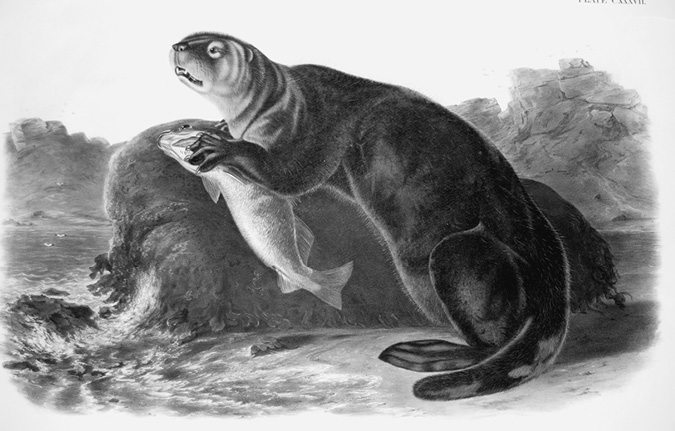

The passage was never found, but one discovery had a major impact on subsequent events. It began innocently enough in March 1778, when Cook’s ships reached the Pacific Northwest coast and anchored in Nootka Sound on the west side of present-day Vancouver Island. The local Indians paddled out to the ships in their canoes, and, according to Cook, “a trade commenced betwixt us and them, which was carried on with the strictest honesty on both sides. The articles which they offered to sale were skins of various animals, such as bears, wolves, foxes, deer, raccoons, polecats, martens; and, in particular, . . . sea otters.”13 Cook’s men snapped up the furs to make new clothes to replace theirs, which were in tatters after nearly two years at sea, giving the Indians “knives, chisels, pieces of iron and tin, nails, looking-glasses, and buttons.” In the coming months Cook’s crew would accumulate fifteen hundred pelts in all.14

Although Cook’s men had acquired the pelts for strictly utilitarian purposes, when they arrived at the port of Canton, China, in late 1779, they realized they had a veritable fortune on their hands. The Chinese, who treasured furs for their warmth and beauty, were willing to pay exorbitant prices. Of all the pelts the men had, the most valuable were the sea otters’, for good reason. The sea otter (Enhydra lutris) is enveloped in a sensationally lustrous and soft fur coat that is the densest of any mammal, with as many as one million hairs per square inch. One nineteenth-century American merchant declared that it gave him “more pleasure to look at a splendid sea-otter skin, than to examine half the pictures that are stuck up for exhibition, and puffed up by pretended connoisseurs. . . . Excepting a beautiful woman and a lovely infant,” the sea otter’s pelt was, he maintained, the most beautiful natural object in the world.15 Particularly fine skins commanded as much as $120 apiece in Canton, and even worn-out pelts garnered a good price. Such huge sums had a galvanizing effect on the men, precipitating in them an almost uncontrollable urge to return immediately to the Pacific Northwest to gather more furs. In fact a near mutiny ensued, but order was maintained, and the ships returned to London in early 1780.16

SEA OTTER, BY JOHN WOODHOUSE AUDUBON, 1845–47.

Ledyard didn’t forget those wondrous transactions in Canton, and when, at the age of thirty-two, he returned to America in 1782, he wrote a book about his adventures with Captain Cook, including the riches of the northwestern fur trade. “The skins,” Ledyard wrote, “which did not cost the purchaser six pence sterling sold in China for 100 dollars. Neither did we purchase a quarter part of the beaver and other fur skins we might have done, and most certainly should have done had we known of meeting the opportunity of disposing of them to such an astonishing profit.”17 Ledyard predicted that his book, published in June 1783, would be “essentially useful to America in general but particularly to the northern states by opening a most valuable trade across the North Pacific Ocean to China & the East Indies” (“East Indies” was a catchall phrase used at the time that typically included China, India, Japan, and the rest of the Far East).18 Before his book was published Ledyard was already looking for investors to back his fur-trading plan. Rebuffed in New York City, he ventured to Philadelphia and was granted a meeting with Morris in early June 1783. There he found a receptive audience, for Ledyard’s plan suggested immense profits, and Morris was finally ready for a China voyage. After his second meeting with Morris, Ledyard wrote to one of his cousins with the joyous news:

I have been so often the sport of fortune, that I durst hardly credit the present dawn of bright prospects. But it is a fact, that the Honorable Robert Morris is disposed to give me a ship to go to the North Pacific Ocean. . . . What a noble hold he instantly took of the enterprise! I have been two days, at his request, drawing up a minute detail of a plan, and an estimate of the outfits, which I shall present him with tomorrow. . . . I take the lead of the greatest commercial enterprise, that has ever been embarked on in this country; and one of the first moment, as it respects the trade of America.19

Morris partnered with Daniel Parker & Company of New York, including Holker and other merchants. The goal was to send three ships around Cape Horn, with one heading for China while the other two would sail to the Pacific Northwest for furs, then to Canton. As Parker and Ledyard looked for ships, Morris and Parker worked on financing the scheme and landing a group of Boston investors.

That summer Parker purchased a splendid ship nearing completion in Boston, designed by the “celebrated” John Peck, whom many regard as America’s first naval architect. Christened Empress of China, at just over one hundred feet long, twenty-eight feet wide, and 360 tons burden, the copper-bottomed, black-hulled vessel was graceful, with clean lines, yet sturdy and strong. It was patterned after the Bellisarius, an American privateer that had been captured by the British during the Revolution and was found to be the fastest ship in the Royal Navy.20

The public first heard of the planned expedition in late August, when the Salem Gazette published an exciting bit of news:

We hear that a ship is fitting out at Boston for an intended voyage to CHINA; that her cargo out, in money and goods, will amount to £150,000; and that she will sail the ensuing fall. Many eminent merchants, in different parts of the continent, are said to be interested in this first adventure from the New World to the Old. We have, at an earlier period than the most sanguine Whig could have expected, or even hoped, or than the most inveterate Tory feared, very pleasing prospects of a very extensive commerce with the most distant parts of the globe.21

Convinced that they should be thinking bigger, Morris and Parker pursued an even more extravagant design, involving not three ships but a small flotilla of half a dozen, with three heading west via Cape Horn, while the others sailed east, around the Cape of Good Hope and across the Indian Ocean to China. No sooner had this new plan been hatched than it began to fall apart. Parker and Ledyard had difficulty lining up additional ships. Skittish Boston investors failed to buy in, forcing Parker’s group and Morris to split the cost. And Morris, still enmeshed in efforts to get the nation’s finances in order, could not give the China project his full attention, while his partners resorted to bickering and maneuvering against one another.

In late November, however, Morris remained confident enough about the prospects for the enterprise to write to John Jay, his friend and one of the signers of the Treaty of Paris, with promising news: “I am sending some ships to China to encourage others in the adventurous pursuits of commerce.” But even this was too optimistic. By early December, as the hard winter enveloped the coast in snow and ice, the China fleet had been reduced to one. Only the Empress of China would be sailing, and it would not be heading west. Morris and Parker couldn’t afford more ships, nor were they willing to stake their entire bet on Ledyard’s untested scheme, but rather decided to follow the safer eastern course taken by European merchants who had already successfully made their way to China.22

Ledyard was furious. “The flame of enterprise that I excited in America,” he confided bitterly to one of his cousins, “terminated in a flash, that equally bespoke the inebriety of head & pusillanimity of heart of my patrons.”23 Rather than give up, however, Ledyard sailed for Europe looking for investors who shared his vision and were willing to see it through.

LACKING LEDYARD’S NORTHWESTERN FURS, the Empress of China would have a cargo of roughly thirty-two tons of lead, fifty tons of cordage, five hundred yards of woolen cloth, twelve casks of spirits (wine, brandy, and rum), a box of furs (mainly beaver), $20,000 in Spanish silver coins (specie), and nearly thirty tons of ginseng. Together, ship and cargo represented an enormous investment of $120,000, of which the silver and the ginseng were the most valuable.24

SPANISH AMERICAN DOLLARS, OR PIECES OF EIGHT, FROM 1791 AND 1807, MINTED IN MEXICO CITY.

The world’s economy at this time literally ran on silver, and more specifically Spanish pieces of eight, the “first truly global currency.”* Since the 1500s the mines in Mexico and South America had produced a genuine flood of the precious metal—more than 3 billion ounces, the vast majority of the world’s supply—which was transformed into coinage that greased mercantile transactions from West to East. There was no doubt that the silver coins on the Empress of China, referred to as “Spanish Dollars” by the Americans, would be most welcome in Canton.25 The same could be said for ginseng.

For thousands of years the Chinese had used the thick, fleshy roots of Panax ginseng, found in the forests of northern China, as an energy booster, an aphrodisiac, and a curative for an impressive array of maladies, including pleurisy, poor vision, dizziness, and vomiting. No wonder, then, that Carl Linnaeus named the genus Panax, which is Greek for “cure-all”; thus, the word “panacea.” To the Chinese ginseng truly was “the dose for immortality.”26

Prior to the early 1700s only Panax ginseng had been used in China. In 1717, however, the Jesuit priest Joseph-François Lafitau discovered another, less potent though still highly desirable species of ginseng growing in Canada—Panax quinquefolius. Soon the French were feverishly digging up Canadian ginseng and sending it to Canton. Not long thereafter Panax quinquefolius was found growing in the mountains and forests of New England, New York, and farther south, and the Americans began selling ginseng to the British East India Company for the China trade.

Both the French and the Americans relied primarily on Indians to gather ginseng, because they were relatively cheap labor and were very familiar with the root, having long used it for medicinal purposes. This arrangement alarmed the conservative American theologian Jonathan Edwards. Writing to a friend in 1752, Edwards noted that the recent discovery of ginseng in the woods of New England and New York had “much prejudiced the cause of religion among the Indians,” because they were spending so much time digging for ginseng that they were not coming to church. Even worse in Edward’s eyes was the Indians’ using their wages to buy rum, “wherewith they have intoxicated themselves.”27

Regardless of the dangers of ginseng to the mortal souls and physical well-being of the Indians, they, and many non-Indians as well, continued to scour America’s forests for the valuable root. And now with the Empress of China’s hold to fill, it was time for the Americans to do the buying. In late August 1783 Parker hired a Philadelphia ginseng supplier, who in turn enlisted Doctor Robert Johnston to purchase ginseng in the small towns, outposts, and Indian lands of Virginia and Pennsylvania. Johnston, who would go on to become the surgeon aboard the Empress of China, spent more than three months in his peripatetic search for the prized root. When he wasn’t traveling through the wilderness to procure ginseng—made scarce as a result of decades of collecting—he was shuttling to Philadelphia and New York to beg for the scarcest commodity of all, money with which to pay his far-flung suppliers. These obstacles notwithstanding, Johnston succeeded in gathering roughly thirty tons of ginseng. Between mid-November and mid-December this impressive haul was sent on a small armada of ships to New York, where it was sorted for quality, stored in 242 casks, and loaded onto the Empress of China.28

AS IMPORTANT AS THE SHIP’S cargo was its captain, on whose back rested the fate of the voyage. John Green, forty-seven, cut an imposing figure at six feet four inches tall and nearly three hundred pounds. With admirable concern for prospective pallbearers, Green had directed in his will that his coffin be “carried to the grave by eight laboring men of the neighborhood.”29 Arriving in Philadelphia from Ireland as a teenager, Green had worked for Willing, Morris & Company as a shipmaster. During the war Green commanded privateers in which Morris had an interest, and also saw action as a captain in the Continental navy. But his luck ran out in the late summer of 1781, when his ship, Lion, was captured by the British frigate La Prudente, after a fourteenth-hour chase off the Brittany coast. Green spent thirty days’ detention on a British man-of-war, and then the next nine months at the notorious Mill Prison, in Plymouth, England, where he passed much of the time building ship models, caring for his fellow prisoners, and waging a letter-writing campaign for his and their freedom. Finally, in late June 1782, with peace negotiations under way, the British Admiralty approved a prisoner release, which sent Green along with 215 other Americans back to Philadelphia. Upon Green’s return one of the local newspapers lauded his selflessness during incarceration. “In every apparent respect, where the honor or credit of our republic were concerned . . . he always demeaned himself in such a manner as justly entitles him to the good-will and thanks of his country.”30

Just as critical as the captain were the supercargoes, the men responsible for overseeing business activities, including the trading that would take place in China. The senior supercargo on the Empress of China was Samuel Shaw, a twenty-nine-year-old Bostonian, who had distinguished himself during the Revolution in a variety of army posts, including aide-de-camp to Major General Henry Knox, the former bookseller who would go on to become America’s first secretary of war. At the war’s end Knox heaped praise upon his aide, noting that he “has, in every instance, evinced himself an intelligent, active, and gallant officer, and as such he has peculiarly endeared himself to his numerous acquaintances,” sentiments that were echoed by Washington as well. The junior supercargo was Thomas Randall, another Bostonian and a close friend of Shaw’s, who served with him in the army and after a short time as a prisoner of war became a successful Philadelphia merchant.31

SAMUEL SHAW.

These three men—Green, Shaw, and Randall—along with Johnston and another officer on the Empress of China, as well as Parker and Morris, shared a connection that extended beyond the ship. They were all members of the Society of the Cincinnati (Morris only honorary), a group conceived by Knox and founded in May 1783 by officers of the Continental army. The society promoted continuing friendship and the cause of union among the states, and it assisted the widows and children of its deceased members. In honor of France’s support during the war, French officers were also welcome to join. The society was named after Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, the Roman farmer turned soldier who heeded the call of his countrymen to become dictator and then led them to victory in two wars, only to return to his farm after the victories rather than retain the mantle of absolute power that his grateful followers had gladly bestowed. Fittingly Washington, the society’s first president general, was widely hailed as the “Cincinnatus of the West,” for his selfless behavior at the end of the American Revolution, when he refused the urgings of some to become king. Having been united in the fight for independence during the war, the Cincinnati men of the Empress of China now made common cause for their country on the battlefield of international commerce.32

WHILE THE BACKERS of the Empress of China were developing their plans, gathering a cargo, and filling out the ship’s complement, other American merchants were also eagerly looking to the Far East—Morris and Parker weren’t the only ones who sensed opportunity. Salem men were known to be interested in trade with China; and in late 1783, Col. Isaac Sears, a Boston merchant, sent a ship in that direction. Earlier in the year one of Sears’s European contacts claimed that five tons of American ginseng would sell in the Swedish port of Gothenburg for eight dollars per pound, as long as it arrived by February 20, 1784, to be transshipped to Canton on Swedish ships. Sears proceeded to purchase the ginseng, but it proved to be a race against time. In order to get the ginseng to Gothenburg on schedule, Sears estimated that he would need to ship it out on his fifty-ton sloop, the Harriet, by the middle of December. Sears failed to make that deadline, so he literally changed course.

According to the story most often told in history books, when the Harriet sailed in late December, Sears told its captain, a Mr. Hallet, to go to Canton, but the sloop never made it that far. In Cape Town, near the southern tip of Africa, the Harriet caught the attention of officers of the British East India Company, who realized that Hallet’s designs ran counter to Britain’s economic interests in China. To eliminate the threat they bought Hallet off, offering him two pounds of Chinese tea for each pound of ginseng. The deal struck, Hallet headed home with a healthy profit.

As dramatic as the story may be, it is in fact apocryphal. While it is possible that the British officers thought they had stymied the competition by their quick dealing, that wasn’t the case. Sears meant to send the Harriet only as far as Cape Town, not China. He knew that Cape Town was a popular stopping-off point for ships engaged in the China trade, and he hoped that Hallet would find a buyer there. Thus, although the voyage of the Harriet is interesting, it was not the first ship from the United States to attempt to go to China.

The Harriet’s return to the United States in July 1784 gave Americans a tangible example of just how radically the world had changed, and it offered a glimpse of a brighter commercial future. One patriotic citizen crowed that the Harriet’s arrival “must fill with sensible pleasure the breast of every American, and cause their hearts to expand with gratitude to the Supreme Ruler of the universe, by whose beneficence our commerce is freed from those shackles it used to be cramped with, and bids fair to extend to every part of the globe, without passing through the medium of England, that rotten island.” Even more tangible was the tea in the Harriet’s hold, which Bostonians eagerly purchased.33

BY EARLY FEBRUARY 1784 the Empress of China, still in port when the Harriet sailed from Boston, was ready to go, with cargo loaded, clearance papers signed, and the officers and crew standing by. Tucked away in Green’s cabin was a most interesting document, thought essential to the trip’s success. Since the voyage was so utterly novel, the owners were not sure how their ship would be received in China. So they figured it was wise to arm Green with an official introduction from the government of the United States, in case the legitimacy of the ship and its purpose were questioned. The sea letter provided by the Continental Congress contained a comically long and rather obsequious salutation, designed to be of use wherever the ship alighted, in or outside of China. It began, “Most serene, serene, most puissant, puissant, high, illustrious, noble, honorable, venerable, wise, and prudent Emperors, Kings, Republics, Princes, Dukes, Earls, Barons, Lords, Burgo-Masters, Counsellors, as also Judges, Officers, Justiciaries and Regents of all the good cities and places, whether ecclesiastical or secular, who shall see these patents or hear them read.” The letter went on to clarify that the Empress of China “belongs to” the citizens of the United States, and to ask that those who welcome Green may do so “with goodness and treat him in a becoming manner,” while allowing him to “transact his business where and in what manner he shall judge proper.”34

When the deep freeze finally broke on February 22, the Empress of China sailed down the East River past the Grand Battery and Fort George at the tip of Manhattan, where a throng of people onshore let out three cheers. Green ordered his men to fire a thirteen-gun salute to represent the thirteen states, to which the fort responded with cannon blasts of its own. As Green gazed upon the exhilarating scene, he couldn’t miss the American flag fluttering in the breeze over the fort. So much had changed in such a short time. A mere three months earlier British forces had occupied New York City, and it was the Union Jack, not the Stars and Stripes, that flew over the fort. The British finally left in the early afternoon of November 25, 1783, later christened Evacuation Day, but before departing they heaped one more insult upon their former colonists.

No sooner had the British embarked than American troops, led by Knox and accompanied by jubilant New Yorkers, paraded into Fort George to prepare for the triumphant arrival of General Washington and the official reclaiming of the city. The crowd’s excitement turned into anger when they saw the Union Jack on the flagpole, and their anger became rage when they realized that the British had nailed their flag in place and greased the pole. After a few men tried unsuccessfully to scale the pole to remove the offending symbol, a call went out to go to gather saws, wood, and nails. Cleats were affixed to the pole, and a young sailor started to climb, but before he got too far, a ladder arrived, which he used to reach the top, tear down the British flag, and replace it with America’s colors, resulting in shouts of joy and a thirteen-gun salute.35

As the Empress of China passed within view of the fort, the British and their disdain were gone. “If we may judge from the countenances of the spectators,” the New York Packet and the American Advertiser observed, “all hearts seemed glad, contemplating the new source of riches that may arise to this city, from a trade to the East-Indies; and all joined their wishes for the success of the Empress of China.”36 Another paper added, “The Captain and crew . . . were all happy and cheerful, in good health and high spirits; and with a becoming decency, elated on being considered the first instruments, in the hands of Providence, who have undertaken to extend the commerce of the United States of America to that distant and to us unexplored country.”37

Philip Freneau, known as the “Poet of the American Revolution,” wrote a heartfelt and patriotic piece to honor the occasion, of which a few stanzas will suffice:

With clearance from Bellona* won

She spreads her wings to meet the Sun,

Those golden regions to explore

Where George forbade to sail before.

. . .

To countries placed in burning climes

And islands of remotest times

She now her eager course explores,

And soon shall greet Chinesian shores.

From thence their fragrant teas to bring

Without the leave of Britain’s king;

And Porcelain ware, enchased in gold,

The product of that finer mould.

. . .

Great pile proceed!—and o’er the brine

May every prosperous gale be thine,

’Till freighted deep with Asia’s stores,

You reach again your native shores.38

Duly feted on its departure, the Empress of China crossed the Atlantic, stopping first at Cape Verde, and then sailed around the tip of Africa and across the Indian Ocean, arriving on July 18 at the Sunda Strait, between Java and Sumatra. The only real excitement up to that point occurred less than two weeks after leaving New York, when a ferocious week-long Atlantic gale pummeled the ship, once generating a huge wave that broke over the stern and stove in a cabin window, and another time causing the ship to roll so hard that Captain Green careened against a deck railing, bruising his arm and head. Other than that, according to the purser, John Swift, thus far it had been an exceedingly boring trip. “We have had no agreeable passage,” he wrote to his father. “It has been one dreary waste of sky & water, without a pleasing sight to cheer us. I am heartily tired of so long a voyage, more especially as we are not yet at our journey’s end by about sixteen hundred miles.” Swift’s grumblings notwithstanding, the Empress of China was having a “textbook” trip, with Green relying on Samuel Dunn’s recently published A New Directory for the East-Indies for maps and sailing directions.39 Now, at the Sunda Strait, poised to cross the Java and South China Seas, Captain Green’s situation grew far more interesting and potentially dangerous, fraught with navigational challenges and the ever-present threat of well-armed pirates, who patrolled the shipping lanes and attacked merchant ships with ruthless efficiency. At that moment, however, a friend appeared.

On the day the Empress of China arrived at the strait, two French ships, the Triton and the Fabius, lay at anchor in one of the bays. Captain d’Ordelin of the Triton and a few of his officers visited the Empress of China to welcome the Americans and invite them to dinner the next evening. Onboard the Triton, as the brandy flowed, there was talk about the Revolution, and how the Americans and their French allies had triumphed over the mighty British lion. Adding to the bonhomie was d’Ordelin’s news that the day before he left Paris, Lafayette had been granted the Order of the Society of the Cincinnati, and that the French people were “much pleased with the honor done to their nation by the institution.” Better than the warm feelings was d’Ordelin’s offer to escort the Empress of China to their mutual destination. The French captain had been to China eleven times before, and therefore knew the way and which hazards to avoid. And since the Triton carried sixteen light cannon and 184 men its presence would force pirates to think twice before attacking.40

At sunrise on July 22 the Empress of China and the Triton got under way; and a little more than a month later they entered the broad Pearl River (Zhujiang) estuary in China. The representatives of the newest country in the world were about to come face-to-face with those of one of the oldest. Americans were finally entering the Middle Kingdom.