Map: Sevilla Shopping & Nightlife

▲▲▲FLAMENCO

WEST OF AVENIDA DE LA CONSTITUCIÓN

BARRIO SANTA CRUZ AND CATHEDRAL AREA

BETWEEN THE CATHEDRAL AND THE RIVER

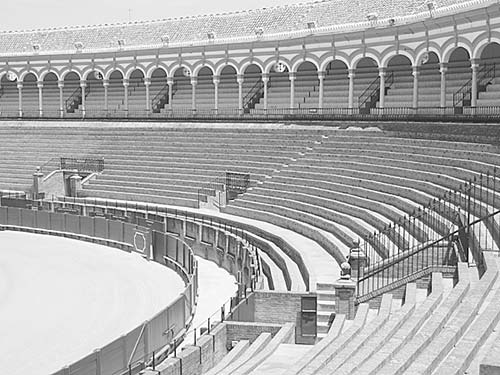

Flamboyant Sevilla (seh-VEE-yah) thrums with flamenco music, sizzles in the summer heat, and pulses with passion. It’s a place where bullfighting is still politically correct and little girls still dream of being flamenco dancers. While Granada has the great Alhambra and Córdoba has the remarkable Mezquita, Sevilla has soul. As the capital of Andalucía, Sevilla offers a sampler of every Spanish icon, from sherry to matadors to Moorish heritage to flower-draped whitewashed lanes. It’s a wonderful-to-be-alive-in kind of place.

As the gateway to the New World in the 1500s, Sevilla boomed when Spain did. The explorers Amerigo Vespucci and Ferdinand Magellan sailed from its great river harbor, discovering new trade routes and abundant sources of gold, silver, cocoa, and tobacco. For more than a century, it all flowed in through the port of Sevilla, bringing the city into a Golden Age. By the 1600s, Sevilla had become Spain’s largest and wealthiest city, home to artists like Diego Velázquez and Bartolomé Murillo, who made it a cultural center. But by the 1700s, Sevilla’s Golden Age was ending, as trade routes shifted, the harbor silted up, and the Spanish empire crumbled.

Nevertheless, Sevilla remained a major stop on the Grand Tour of Europe. European nobles flocked here in the 19th century, wanting to see for themselves the legendary city from story and song: the daring of Don Giovanni (Don Juan), the romance of Carmen, the spine-tingling cruelty of the Spanish Inquisition, and the comic gaiety of The Barber of Seville. To build on this early tourism, Sevilla planned a grand world’s fair in 1929. Bad year. But despite the worldwide depression brought on by the US stock market crash, two million visitors flocked to see Sevilla’s new parks and new neighborhoods, which are still beautiful parts of the city. In 1992, Sevilla got a second chance, and this world’s fair was an even bigger success, leaving the city with impressive infrastructure: a new airport, six sleek bridges, a modern train station, and the super AVE bullet train (making Sevilla a 2.5-hour side-trip from Madrid). In 2007, the main boulevards—once thundering with noisy traffic and mercilessly cutting the city in two—were pedestrianized, enhancing Sevilla’s already substantial charm.

Today, Spain’s fourth-largest city (pop. 700,000) is Andalucía’s leading destination, buzzing with festivals, color, guitars, castanets, and street life, and enveloped in the fragrances of orange trees and myrtle. Sevilla also has its share of impressive sights. It’s home to the world’s largest Gothic cathedral. The Alcázar is a fantastic royal palace and garden ornamented with Islamic flair. But the real magic is the city itself, with its tangled former Jewish Quarter, riveting flamenco shows, thriving bars, and teeming evening paseo. As James Michener wrote, “Sevilla doesn’t have ambience, it is ambience.”

On a three-week trip, spend three nights and two days here. On even the shortest Spanish trip, I’d zip here on the slick AVE train for a day trip from Madrid. With more time, if ever there was a Spanish city to linger in, it’s Sevilla.

The major sights are few and simple for a city of this size. The cathedral and the Alcázar can be seen in about three hours—but only if you buy tickets in advance. A wander through the Barrio Santa Cruz district takes about an hour.

You could spend a second day touring Sevilla’s other sights. Stroll along the bank of the Guadalquivir River and cross Isabel II Bridge to explore the Triana neighborhood and to savor views of the cathedral and Torre del Oro. An evening in Sevilla is essential for the paseo and a flamenco show. Stay out late to appreciate Sevilla on a warm night—one of its major charms.

Córdoba (see next chapter) is the most convenient and worthwhile side-trip from Sevilla, or a handy stopover if you’re taking the AVE to or from Madrid or Granada. Other side-trip possibilities include Arcos or Jerez.

For the tourist, this big city is small. The bull’s-eye on your map should be the cathedral and its Giralda bell tower, which can be seen from all over town. Nearby are Sevilla’s other major sights, the Alcázar (palace and gardens) and the lively Barrio Santa Cruz district. The central north-south pedestrian boulevard, Avenida de la Constitución, stretches north a few blocks to Plaza Nueva, gateway to the shopping district. A few blocks west of the cathedral are the bullring and the Guadalquivir River, while Plaza de España is a few blocks south. The colorful Triana neighborhood, on the west bank of the Guadalquivir River, has a thriving market and plenty of tapas bars, but no major tourist sights. While most sights are within walking distance, don’t hesitate to hop in a taxi to avoid a long, hot walk (they are plentiful and cheap).

Sevilla has tourist offices at the airport (Mon-Fri 9:00-19:30, Sat-Sun 9:30-15:00, +34 954 782 035), at Santa Justa train station (just inside the main entrance, same hours as airport TI, +34 954 782 002), and near the cathedral on Plaza del Triunfo (Mon-Fri 9:00-19:30, Sat-Sun from 9:30, +34 954 210 005).

At any TI, ask for the English-language magazine The Tourist (also available at www.thetouristsevilla.com) and a current listing of sights with opening times. The free monthly events guide—El Giraldillo, written in Spanish basic enough to be understood by travelers—covers cultural events throughout Andalucía, with a focus on Sevilla. You can also ask for information you might need for elsewhere in the region (for example, if heading south, pick up the free Route of the White Towns brochure and a Jerez map). Helpful websites are www.turismosevilla.org and www.andalucia.org.

Steer clear of the “visitors centers” on Avenida de la Constitución (near the Archivo General de Indias) and at Santa Justa train station (overlooking tracks 6-7), which are private enterprises.

By Train: All long-distance trains arrive at modern Santa Justa station, with banks, ATMs, and a TI. Baggage storage is below track 1 (follow signs to consigna, security checkpoint open 6:00-24:00). The easy-to-miss TI sits by the sliding doors at the main entrance, to the left before you exit. The plush little AVE Sala Club, designed for business travelers, welcomes those with a first-class AVE ticket and reservation (across the main hall from track 1). The town center is marked by the ornate Giralda bell tower, peeking above the apartment flats (visible from the front of the station—with your back to the tracks, it’s at 1 o’clock). To get into the center, it’s a flat and boring 25-minute walk or about an €8 taxi ride. By city bus, it’s a short ride on #C1 or #21 to the El Prado de San Sebastián bus station (find bus stop 100 yards in front of the train station, €1.40, pay driver), then a 10-minute walk or short tram ride (see next section).

Regional trains use San Bernardo station, linked to the center by a tram (see “Getting Around Sevilla,” later).

By Bus: Sevilla’s two major bus stations—El Prado de San Sebastián and Plaza de Armas—both have information offices, basic eateries, and baggage storage.

The El Prado de San Sebastián bus station, or simply “El Prado,” covers most of Andalucía (information desk, daily 8:00-20:00, +34 955 479 290, generally no English spoken; baggage lockers/consigna at the far end of station, same hours). From the bus station to downtown (and Barrio Santa Cruz hotels), it’s about a 15-minute walk: Exit the station straight ahead. When you reach the busy avenue (Menéndez Pelayo) turn right to find a crosswalk and cross the avenue. Enter the Murillo Gardens through the iron gate, emerging on the other side in the heart of Barrio Santa Cruz. Sevilla’s tram connects the El Prado station with the city center (and many of my recommended hotels): Turn left as you exit the bus station and walk to Avenida de Carlos V (€1.40, buy ticket at machine before boarding; ride it two stops to Archivo General de Indias to reach the cathedral area, or three stops to Plaza Nueva).

The Plaza de Armas bus station (near the river, opposite the Expo ’92 site) serves long-distance destinations such as Madrid, Barcelona, Lagos, and Lisbon. Ticket counters line one wall, an information kiosk is in the center, and at the end of the hall are pay luggage lockers (buy tokens at info kiosk). Taxis to downtown cost around €7. Or, to take the bus, exit onto the main road (Calle Arjona) to find bus #C4 into the center (stop is to the left, in front of the taxi stand; €1.40, pay driver, get off at Puerta de Jerez).

By Car: To drive into Sevilla, follow Centro Ciudad (city center) signs. The city is no fun to drive in and parking can be frustrating. If your hotel lacks parking or a recommended plan, I’d pay for a garage (€24/day) and grab a taxi to your hotel from there. For hotels in the Barrio Santa Cruz area, the handiest parking is the Cano y Cueto garage near the corner of Calle Santa María la Blanca and Avenida de Menéndez Pelayo (open daily 24 hours, at edge of big park, underground).

By Plane: Sevilla’s San Pablo Airport sits about six miles east of downtown and has several car rental agencies in the arrivals hall (airport code: SVQ, +34 954 449 000, www.aena.es). The Especial Aeropuerto (EA) bus connects the airport with Santa Justa and San Bernardo train stations, both bus stations, and several stops in the town center (4/hour, less in off-peak hours, runs 4:30-24:00, 40 minutes, €4, pay driver). The two most convenient stops downtown are south of the Murillo gardens on Avenida de Carlos V, near El Prado de San Sebastián bus station (close to my recommended Barrio Santa Cruz hotels); and on the Paseo de Cristóbal Colón, near the Torre del Oro. Look for the small EA sign at bus stops. If you’re going from downtown Sevilla to the airport, the bus stop is on the side of the street closest to Plaza de España. To taxi into town, go to an airport taxi stands to ensure a fixed rate (€23 by day, €27 at night and on weekends, luggage extra, confirm price with driver before your journey).

Festivals: Sevilla’s peak season is April and May, and it has two one-week spring festival periods when the city is packed: Holy Week and April Fair.

While Holy Week (Semana Santa) is big all over Spain, it’s biggest in Sevilla. Held the week between Palm Sunday and Easter Sunday, locals prepare for the big event starting up to a year in advance. What would normally be a five-minute walk can take an hour if a religious procession crosses your path, and many restaurants stop serving meat during this time. But any hassles become totally worthwhile as you listen to the saetas (spontaneous devotional songs) and give in to the spirit of the festival.

Then, after taking two weeks off to catch its communal breath, Sevilla holds its April Fair (April 18-24 in 2021). This is a celebration of all things Andalusian, with plenty of eating, drinking, singing, and merrymaking (though most of the revelry takes place in private parties at a large fairground).

Book rooms well in advance for these festival times. Prices can be sky-high and many hotels have four-night minimums.

Rosemary Scam: In the city center, and especially near the cathedral, you may encounter women thrusting sprigs of rosemary into the hands of passersby, grunting, “Toma! Es un regalo!” (“Take it! It’s a gift!”). The twig is free...but then they grab your hand and read your fortune for a tip. Coins are “bad luck,” so the minimum payment they’ll accept is €5. They can be very aggressive, but you don’t need to take their demands seriously—don’t make eye contact, don’t accept a sprig, and say firmly but politely, “No, gracias.”

Laundry: Lavandería Tintorería Roma offers quick and economical drop-off service (Mon-Fri 10:00-14:00 & 17:30-20:30, Sat 10:00-14:00, closed Sun, a few blocks west of the cathedral at Calle Arfe 22, +34 954 210 535). Near the recommended Barrio Santa Cruz hotels, La Segunda Vera Tintorería has two self-service machines (Mon-Fri 9:30-14:00 & 17:30-20:30, Sat 10:00-13:30, closed Sun, about a block from the eastern edge of Barrio Santa Cruz at Avenida de Menéndez Pelayo 11, +34 954 536 376). For locations, see the “Sevilla Hotels” map, later.

Bike Rental: This biker-friendly city has designated bike lanes and a public bike-sharing program (€14 one-week subscription, first 30 minutes of each ride free, €2 for each subsequent hour, www.sevici.es). Ask the TI about this and other bicycle-rental options.

Most visitors have a full and fun experience in Sevilla without ever riding public transportation. The city center is compact, and most of the major sights are within easy walking distance.

By Taxi: Sevilla is a great taxi town; they’re plentiful and cheap. Two or more people should go by taxi rather than public transit. You can hail one showing a green light anywhere, or find a cluster of them parked by major intersections and sights (€1.35 drop rate, €1/kilometer, €3.60 minimum; about 20 percent more on evenings and weekends; calling for a cab adds about €3). A quick daytime ride in town will generally fall within the €3.60 minimum. Although I’m quick to take advantage of taxis, note that because of one-way streets and traffic congestion it’s often just as fast to hoof it between central points.

By Bus, Tram, and Metro: A single trip on any form of city transit costs €1.40. Skip the various transit cards—they are a hassle to get and not a good value for most tourists. Various #C buses, which are handiest for tourists, make circular routes through town (note that all of them except the #C6 eventually wind up at Basílica de La Macarena). For all buses, buy your ticket from the driver or from machines at bus stops. The #C3 stops at Murillo Gardens, Triana, then La Macarena. The #C4 goes the opposite direction, but without entering Triana. And the spunky #C5 minibus winds through the old center of town, including Plaza del Salvador, Plaza de San Francisco, the bullring, Plaza Nueva, the Museo de Bellas Artes, La Campana, and La Macarena, providing a relaxing joyride that also connects some farther-flung sights (see route on “Sevilla” map).

A tram (tranvía) makes just a few stops in the heart of the city but can save you a bit of walking. Buy your ticket at the machine on the platform before you board (runs about every 7 minutes Sun-Thu until 23:00, Fri-Sat until 1:45 in the morning). It makes five city-center stops (from south to north): San Bernardo (at the San Bernardo train station), Prado San Sebastián (next to El Prado de San Sebastián bus station), Puerta Jerez (south end of Avenida de la Constitución), Archivo General de Indias (next to the cathedral), and Plaza Nueva (beginning of shopping streets).

Sevilla also has a one-line underground Metro, but it’s of little use to travelers since its primary purpose is to connect the suburbs with the center. Its downtown stops are at the San Bernardo train station, El Prado de San Sebastián bus station, and Puerta Jerez.

To sightsee on your own, download my free Sevilla City Walk audio tour.

To sightsee on your own, download my free Sevilla City Walk audio tour.

A joy to listen to, Concepción Delgado is an enthusiastic teacher who takes small groups on English-only walks. Although you can just show up, it’s smart to confirm departure times and reserve a spot (4-person minimum, none on Sun or holidays, mobile +34 616 501 100, www.sevillawalkingtours.com, info@sevillawalkingtours.com). Because she’s a busy mom, Concepción sometimes sends her equally excellent colleagues to lead these tours.

City Walk: This fine two-hour introduction to Concepción’s hometown is a fascinating cultural show-and-tell in which she skips the famous monuments and shares intimate insights the average visitor misses. Other than seeing the cathedral and Alcázar, this to me is the most interesting two hours you could spend in Sevilla (€15/person, Mon-Sat at 10:30, check website for Dec-Feb and Aug schedule, meet at statue in Plaza Nueva).

Cathedral and Alcázar Tours: For those wanting to really understand the city’s two most important sights, Concepción offers 75-minute visits to the cathedral (€12 plus admission) and the Alcázar (€28 including admission, must book in advance). These tours are scheduled to fit efficiently after Concepción’s city walk (€2 discount if combined). Meet at 13:00 at the statue in Plaza del Triunfo (cathedral tours—Mon, Wed, and Fri; Alcázar tours—Tue, Thu, and Sat).

Other Tours: Concepción offers a Tasty Culture tour covering social life and popular traditions (€26, includes a drink and tapa), and a Game of Thrones add-on to the Alcázar tour.

This group of three licensed guides (Susana, Jorge, and Elena) offers quality private tours (€160/3 hours). They also run a Monuments Tour covering the Sevilla basics: cathedral, Alcázar, and Barrio Santa Cruz (€25/person plus admissions, Mon-Sat at 14:00, 2.5 hours, leaves from Plaza del Triunfo, mobile +34 606 217 194, www.allsevillaguides.com).

Julia Rozet adopted Sevilla as her home 12 years ago and specializes in themed tours that explore different facets of the city such as its industrial and seafaring past, Magellan and the history of spices, and locations used for famous operas set in Sevilla. If you visit during one of Sevilla’s many festivals, Julia can explain the traditions behind all the commotion (€20, families with children welcome, mobile +34 633 083 961, www.sevillalacarta.com).

Free tour companies dominate the walking tour scene in Sevilla. They are not “free,” as you’re aggressively hit up for a tip at the end, and you’ll spend a good part of the tour hearing a sales pitch for the companies’ paid offerings. The walk spiel is entertaining but with little respect for history or culture, and your “guide” is often a student who has memorized a script. Still—it’s “free” and you get what you pay for. You’ll see these guides with color-coded umbrellas at various starting points around the city.

For information on tapas tours and cooking lessons, see the sidebar on here.

Two competing city bus tours leave from the curb near the riverside Torre del Oro. You’ll see parked buses and salespeople handing out fliers. Each tour does about an hour-long swing through the city with recorded narration. The tours, which allow you to hop on and off at 14 stops, are heavy on Expo ’29 and Expo ’92 neighborhoods—of limited interest nowadays. While the narration does its best, Sevilla is most interesting in places buses can’t go (daily 10:00-22:00, off-season until 18:00, €22 for red bus: www.city-sightseeing.com; €18 online in advance for green bus: http://sevilla.busturistico.com).

A carriage ride is a classic, popular way to survey the city and to enjoy María Luisa Park (€45 for a 45-minute clip-clop, much more during Holy Week and the April Fair, find a likable English-speaking driver for better narration). There are several departure points around town: Look for rigs at Plaza de América, Plaza del Triunfo, the Archivo General de Indias, the Alfonso XIII Hotel, and Plaza de España.

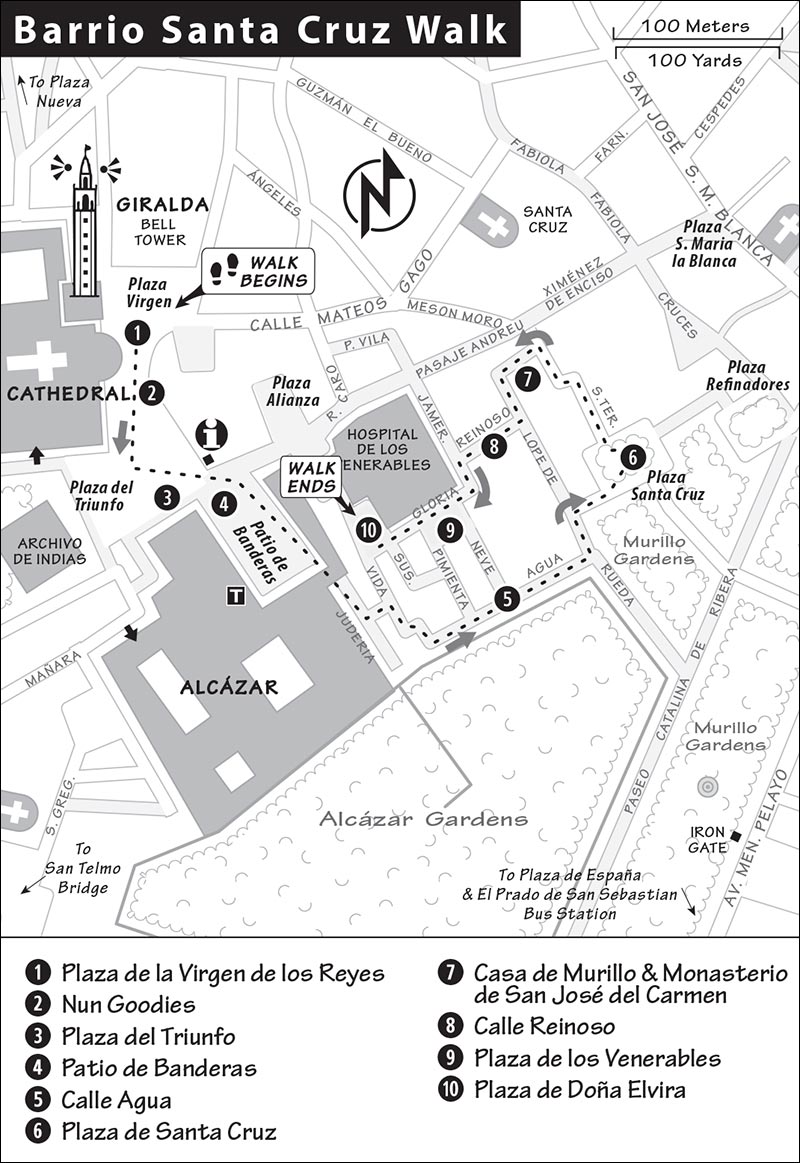

The soul of Sevilla is best found in the narrow lanes of its oldest quarter—the Barrio Santa Cruz. Of Sevilla’s once-thriving Jewish neighborhood, only the tangled street plan and a wistful Old World ambience survive. This classy maze of lanes (too tight for most cars), small plazas, tile-covered patios, and whitewashed houses with wrought-iron latticework draped in flowers is a great refuge from the summer heat and bustle of Sevilla. The streets are narrow—some with buildings so close they’re called “kissing lanes.” A happy result of the narrowness is shade: Locals claim the Barrio Santa Cruz is three degrees cooler than the rest of the city.

The barrio is made for wandering. Getting lost is easy, and I recommend doing just that. But to get started, here’s a self-guided plaza-to-plaza walk that loops you through the corazón (heart) of the neighborhood and back out again. Along the way, we’ll get an introduction to some of the things that give Sevilla its unique charm.

Download my free Sevilla City Walk audio tour, which complements this walk (following stops at the Sevilla Cathedral and Royal Alcazar).

Download my free Sevilla City Walk audio tour, which complements this walk (following stops at the Sevilla Cathedral and Royal Alcazar).

When to Go: Tour groups often trample the barrio’s charm in the morning. I find that early evening—around 19:00—is the ideal time to explore the quarter.

• Start in the square in front of the cathedral, at the lantern-decked fountain in the middle that dates from Expo ’29.

Do a 360-degree spin and take in some of Sevilla’s signature sights. There’s the gangly cathedral with its soaring Giralda bell tower—ground zero of the city. To the right is the ornate red Archbishop’s Palace, a center of power since Christians first conquered the city from the Moors in 1248. Continuing your spin, the next building is almost a cliché of early 20th-century (and now government-protected) Sevillian architecture—whitewashed with goldenrod trim and ironwork balconies. The street stretching away from the cathedral is lined with another Sevillian trademark—tapas bars, housed in typical Andalusian buildings with their ironwork. Continuing your spin, there’s a row of Sevilla’s signature orange trees. Hiding in the orange trees is a statue of Pope John Paul II, who performed Mass here before a half-million faithful Sevillians during a 1982 visit. Finally, you return to the Giralda bell tower.

The Giralda encapsulates Sevilla’s 2,000-year history. The large blocks that form the very bottom of the tower date from when Sevilla was a Roman city. (Up close, you can actually read some Latin inscriptions.) The tower’s main trunk, with its Islamic patterns and keyhole arches, was built by the Moors (with bricks made of mud from the river) as a call-to-prayer tower for a mosque. The top (16th-century Renaissance), with its bells and weathervane figure representing Faith, was added after Christians reconquered Sevilla, tore down the mosque, built the sprawling cathedral—and kept the minaret as their bell tower.

This square is dedicated to that Christian reconquest, and to the Virgin Mary. Turn 90 degrees to the left as you face the cathedral and find (hiding behind the orange trees) the Virgin of the Kings (see her blue-and-gold tiled plaque on the white wall). This is one of the many different versions of Mary you’ll see around town—some smiling, some weeping, some triumphant—each appealing to a different type of worshipper.

Notice the columns and chains that ring the cathedral, as if put there to establish a border between the secular and Catholic worlds. Indeed, that’s exactly the purpose they served for centuries, when Sevillians running from the law merely had to cross these chains to find sanctuary—like crossing the county line. Many of these columns are far older than the cathedral, having originally been made for Roman and Visigothic buildings and later recycled by medieval Catholics.

• Facing the cathedral, turn left and walk toward the next square to find some...

The white building on your left was an Augustinian convent. Step inside the door at #3 to meet (but not see) a cloistered nun behind a fancy torno (a lazy Susan the nuns spin to sell their goods while staying hidden). The sisters raise money by selling rosaries, prayer books, and communion wafers (tabletas—bland, but like sin-free cookies). Consider buying something here just as a donation. The sisters, who speak only Spanish, have a sense of humor—have fun practicing your Spanish with them (Mon-Sat 9:15-13:00 & 16:45-18:15, Sun 10:00-13:00).

• Step into the square marked with a statue of the Virgin atop a pillar. This is...

Bordered by three of Sevilla’s most important buildings—the cathedral, the walled Alcázar, and the Archivo General de Indias (filled with historic papers)—this place was the center of the action during the Golden Age of the 16th and 17th centuries. Businessmen from all over Europe gathered here to trade in the exotic goods pouring in from the New World. That wealth produced a flowering of culture, including Sevilla’s most beloved painter, Bartolomé Murillo, who is honored at the base of the pillar (the sculptor used a famous painting by Murillo for his model of the Immaculate Conception on top).

The “Plaza of Triumph” is named for yet another Virgin statue atop a smaller pillar at the far end of the square. This Virgin helped the city miraculously “triumph” over the 1755 earthquake that destroyed Lisbon but only rattled Sevilla.

• Before leaving the square, consider stopping at the TI. Then pass through the arched opening in the Alcázar’s spiky, crenellated wall. You’ll emerge into a white-and-goldenrod courtyard called the...

The Banderas Courtyard (as in “flags,” not Antonio) was part of the Alcázar, the Spanish king’s residence when he was in town. This square was a military parade ground, and the barracks surrounding it housed the king’s bodyguards.

Before the Alcázar was the palace of the Christian king, it was the palace of the Muslim Moors who ruled Sevilla. Archaeologists found remains of this palace (as well as 2,000-year-old Roman ruins) beneath the courtyard. They excavated it, then covered the site to protect it.

Orange trees abound. Because they never lose their leaves, they provide constant shade. But forget about eating the oranges. They’re bitter and used only to make vitamins, perfume, cat food, and that marmalade you can’t avoid in British B&Bs. But when they blossom (for three weeks in spring, usually in April), the aroma is heavenly. (You can identify a bitter orange tree by its leaves—they have a tiny extra leaf between the main leaf and the stem.)

Head for the arch at the far-left corner of this square, do a 180, and enjoy the view of the Giralda bell tower.

• Exit the courtyard through the Judería arch. Go down the long, narrow passage still paved with its original herringbone brickwork. Emerging into the light, you’ll be walking alongside the red Alcázar wall. Take the first left at the corner lamppost and you’ll pass another gate. A gate here was locked each evening—at first to protect the Jewish community (when they were the privileged elite—bankers, merchants, tax collectors) and later during times of persecution to isolate them (until they were finally expelled in 1492). Passing the gate, go right, through a small square, and follow the long narrow alleyway called...

This narrow lane is typical of the barrio’s tight quarters, born when the entire Jewish community was forced into a small segregated ghetto. As you walk, on your right is one of the older walls of Sevilla, dating back to Moorish times. Glancing to the left, peek through iron gates for occasional glimpses of the flower-smothered patios of restaurants and exclusive private residences (sometimes open for viewing). The patio at #2 is a delight—ringed with columns, filled with flowers, and colored with glazed tiles. The tiles are not merely decorative—they keep buildings cooler in the summer heat. If the gate is closed, try the next door down, or just look up for a hint of the garden’s flowery bounty. Admire the expensive ornamental mahogany eaves.

The plaque above and to the left of #1 remembers Washington Irving. He and Romantic novelists, poets, and painters of his era inspired early travelers and popularized the Grand Tour. Aristocrats back in the 19th century had their favorite stops as they gallivanted around Europe, and Sevilla—with its operettas (like Carmen), bullfighting, and flamenco—was hard to resist.

Emerging at the end of the street, turn around and look back at the openings of two old pipes built into the wall. These 12th-century Moorish pipes once carried fresh spring water to the Alcázar (and today give the street its name—Agua). They were part of a 10-mile-long aqueduct system that was originally built by the ancient Romans and expanded by the Moors, serving some parts of Sevilla until the 1600s. You’re standing at an entrance into the pleasant Murillo Gardens (through the iron gate), formerly the fruit-and-vegetable gardens for the Alcázar.

• Don’t enter the gardens now, but instead cross the square diagonally, and continue 20 yards down a lane to the...

Arguably the heart of today’s barrio, this pleasant square is graced with orange trees and draping vines, with a hedged garden in the center.

This square encapsulates the history of the neighborhood. In early medieval times, it was the Judería, with a synagogue standing where the garden is today. When the Jews were rousted in the 1391 pogrom, the synagogue was demolished, and a Christian church was built on the spot (the Church of Santa Cruz). It was the neighborhood church of the Sevillian painter Bartolomé Murillo (and later his burial site). But when the French (under Napoleon) invaded, the church was demolished. A fine 17th-century iron cross in the center of the square now marks the former site of the church. This “holy cross” (santa cruz), from a renowned Sevillian forge, has inspired similar-looking crosses still carried in Holy Week processions, and gave this former Jewish Quarter its Christian name.

At #9, you can peek into a lovely courtyard that’s proudly been left open so visitors can enjoy it. It’s a reminder of the traditional Andalusian home, built around an open-air courtyard. The square is also home to the recommended Los Gallos flamenco bar, which puts on nightly performances (see “Nightlife in Sevilla,” later).

• Exit the square right of Los Gallos, going uphill (north) on Calle Santa Teresa. Notice millstones in the walls. Tour guides like to say this was a way for a wealthy miller to show off (like someone today parking a fancy car in their driveway). Notice also the well-worn ancient column functioning as a cornerstone. With the ruins of Roman Itálica nearby, Sevilla had a ready quarry for such ornamental corner pieces.

After the kink in the road, find #8 (on the left).

Sevilla’s famous painter, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, lived here in the 17th century. Born and raised in Sevilla, Murillo spent his final years here in this plush two-story mansion with a central patio. He soaked in the ambience of street life in this characteristic barrio and reproduced it in his paintings of cute beggar children. He also painted iconic versions of local saints and took Sevilla’s devotion to the Virgin to another level with his larger-than-life Immaculate Conceptions. Wedding extreme religiosity with down-to-earth street life, he captured the Sevillian spirit.

Directly across from Casa de Murillo is the enormous wooden doorway of the Monasterio de San José del Carmen. This convent was founded by the renowned mystic, St. Teresa of Ávila. When she arrived in Sevilla in 1575, it was Spain’s greatest city, and she stayed here for 10 years. Today, the Baroque convent keeps some of Teresa’s artifacts and spiritual manuscripts, but it’s closed to the public except for early morning Mass (Mon-Fri at 8:45 and Sun at 9:00).

• Continue north on Calle Santa Teresa, then take the first left on Calle Lope de Rueda (just before the popular Las Teresas café). Here you enter a series of very narrow lanes. Take a left again, then right on...

This street—so narrow that the buildings almost touch—is one of the barrio’s “kissing lanes.” A popular explanation suggests the buildings were so close together to provide maximum shade. But the history is more complex than that: This labyrinthine street plan goes back to Moorish times when this area was a tangled market. Later, this was the densely populated Jewish ghetto.

• Leaving the “kissing zone,” just to the left, the street spills onto...

This tiny square is another candidate for “heart of the barrio,” as it captures the romantic ambience that inspired so many operettas in Sevilla (from Don Giovanni and Carmen to The Barber of Seville and The Marriage of Figaro). The square also serves as the lively hub for several narrow streets that branch off it, oozing local color. With its vibrant buildings and visitor-oriented businesses, it typifies the barrio today: traditional and touristy at the same time.

The harmonious red-and-white Sevillian-Baroque Hospital de los Venerables (1675) was once a retirement home for old priests (the “venerable” ones). It’s now a cultural foundation worth visiting for its ornate church and small but fine collection of Sevillian paintings (see listing later, under “Sights in Sevilla”). The ceramic shop at the far end of the square welcomes tourists to use its bus-tour-friendly WCs.

• Pass through the square. On Calle de Gloria is an interesting tile map of the Jewish Quarter. (Find yourself in the lower left, second row up, third tile from the left.) Now continue west on Calle de Gloria, where you’ll soon emerge into...

This square—with orange trees, tile benches, and a stone fountain—sums up our barrio walk. Shops sell work by local artisans, such as ceramics, embroidery, and fans. The plaza has a long history. In the 19th century, aristocrats flocked here to see the supposed home of the legendary lady love of the legendary Don Juan. At night, with candlelight and Spanish guitars playing, this is indeed a romantic place to dine.

But the plaza we see today reflects the fate of much of the barrio. After the neighborhood’s Jews were expelled in 1492, the area went into slow decline. Napoleon’s invasion furthered the destruction. By the early 1900s it was deserted and run down. Sevilla began an extensive urban renewal project, which culminated in the 1929 world’s fair. They turned much of the barrio, including this plaza, into a showcase of Andalusian style. Architects renovated with traditional-style railings, tile work, orange trees, and other too-cute, Epcot-like adornments. The Barrio Santa Cruz may not be quite as old as it appears, but the new and improved version respects tradition while carrying the neighborhood’s 800-year legacy into the future.

• Our walk is over. To return to the area near the start of this walk, cross the plaza and head north along Calle Rodrigo Caro; keep going until you enter the large Plaza de la Alianza. From here, a narrow lane (Calle Joaquín Romero Murube) leads left back to the Alcázar.

BETWEEN THE CATHEDRAL AND THE RIVER

▲Archivo General de Indias (General Archives of the Indies)

Torre del Oro (Gold Tower) and Naval Museum

▲▲Church of the Savior (Iglesia del Salvador)

▲Museo Palacio de la Condesa de Lebrija

▲Flamenco Dance Museum (Museo del Baile Flamenco)

Sevilla’s cathedral (Catedral de Sevilla) is the third-largest church in Europe (after St. Peter’s at the Vatican in Rome and St. Paul’s in London) and the largest Gothic church anywhere. When they ripped down a mosque of brick on this site in 1401, the Reconquista Christians vowed they’d build a cathedral so huge that “anyone who sees it will take us for madmen.” When it was finished in 1528, it was indeed the world’s biggest, and remained so for a century until St. Peter’s came along. Even today, the descendants of those madmen proudly point to a Guinness Book of Records letter certifying, “Santa María de la Sede in Sevilla is the cathedral with the largest area.”

On this self-guided tour, we’ll marvel at the vast interior, over-the-top altars, world-class art, a stuffed crocodile, and the final resting place of Christopher Columbus.

Cost: €10 combo-ticket also includes Giralda bell tower and entry to the Church of the Savior—buy online in advance.

Hours: Tue-Sat 11:00-17:00 (July-Aug until 18:00), Sun 14:30-18:00 (July-Aug 14:00-19:00), Mon 11:00-15:30.

Information: www.catedraldesevilla.es.

Advance Tickets Recommended: It’s smart to buy your ticket online (dates are available starting five weeks in advance) to avoid the long, time-consuming line. Without advance tickets, consider buying your combo-ticket at the Church of the Savior first (though lines there can also be long). Ticket in hand, walk boldly to the front and find the special entry line for advance ticketholders.

If you booked a tour of the rooftop (see later), you can enter the cathedral any time before your scheduled tour. Otherwise, after your tour, the guide can add your name to a list for approved entry the following day.

Tours: The €4 audioguide is excellent. The cathedral offers a guided tour that provides only a little extra information and is overpriced at €17; consider joining Concepción Delgado’s guided tour instead (see “Tours in Sevilla,” earlier).

The cathedral offers a 90-minute guided rooftop visit (€16, includes cathedral entrance, book online, English tours daily June-Sept at 10:30 and 18:00, Oct-May at 12:00 and 16:30, meet at west facade 15 minutes before tour). I prefer the last entry of the day for a more intimate experience. If you do this tour, skip the Giralda tower climb.

My free Sevilla City Walk audio tour includes background detail and descriptions of the cathedral exterior, but doesn’t cover the interior.

My free Sevilla City Walk audio tour includes background detail and descriptions of the cathedral exterior, but doesn’t cover the interior.

Visitor Services: A WC and drinking fountain are just inside the entrance and in the courtyard near the exit.

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided Tour• You’ll enter the church at the south facade (closest to the Alcázar). But before you head inside, take time to circle clockwise around the exterior (you can also do this at the end of the tour).

Sevilla’s cathedral has an odd exterior that is hard to fully appreciate. As the mosque was square and the cathedral was designed to entirely fill its footprint, the transepts don’t show from the outside. And with no great square leading to the church, you hardly know where the front door is (it’s on the west side). The church is circled by pillars and chains, which provided sanctuary to those escaping secular law (but not Christian law) 500 years ago.

Today’s tourists enter through the south facade, which is 19th-century Neo-Gothic and unfinished—notice the empty niches that never got their statues. In the courtyard stands a full-size replica of the Giraldillo statue that caps the bell tower.

The west facade faces the trams, horses, and commotion of Avenida de la Constitución. Though this is the main entry to the cathedral, it seems totally ignored. The central door shows the Assumption of Mary, with the beloved Virgin rocketing up to heaven to be crowned by God with his triangular halo (reminding all of the Trinity). While this part wasn’t finished until the 19th century, the side doors—with their red terra-cotta saints—date from the 15th century.

Continuing around the huge cathedral, at the next corner (across from Starbucks) you’ll see animal-blood graffiti from 18th-century students celebrating their graduation—revealed in a recent cleaning project.

On the north side, the Puerta del Perdón (where you’ll exit at the end of this tour) was once the entry to the mosque’s courtyard. But, as with much of the Moorish-looking art in town, it’s now actually Christian—the two coats of arms are a giveaway. The relief above the door shows the Bible story of Jesus ridding the temple of the merchants...a reminder to contemporaries that there will be no retail activity in the church. (German merchants gathered on this street—notice the name: Calle Alemanes.) The plaque on the right honors Miguel de Cervantes, the great 16th-century writer; this is one of many plaques scattered throughout town showing places mentioned in his books. (In this case, the topic was pickpockets.)

• Circle back to the south facade and enter the cathedral. You’ll pass through the...

This room features paintings that once hung in the church. You’ll see a few by Sevilla’s 17th-century master, Bartolomé Murillo, including paintings of beloved local characters who’ll crop up again on our tour. King (and saint) Ferdinand III—usually shown with sword, crown, globe, and ermine robe—is the man who took Sevilla from the Moors and made this church possible. Santa Justa and Santa Rufina—Sevilla’s patron saints—represent the city’s Christian past. They were killed in ancient Roman times for their Christian faith. Potters by trade, they’re easy to identify by their palm branches (symbolic of their martyrdom), their pots (at their feet or in their hands), and the Giralda bell tower symbolizing the town they protect. As you tour, play slug bug whenever you spot this dynamic hometown duo.

• Now enter the actual church (passing a WC on the way) and take in the...

The church is 137 yards long and 90 yards wide. That’s more than two acres, the size of an entire city block in downtown Manhattan. Measured by area, this is still the world’s largest church. (The church’s footprint needed to be big enough to stamp out every trace of the mosque it replaced.) While most Gothic churches are long and tall, this nave is square and compressed. The pillars are massive. Like other Spanish churches, this nave is clogged in the middle by the huge rectangular enclosure called the choir.

• Walk up the nave, past the choir, to the center of the church, where you can enjoy a view of the main altar. Look through the wrought-iron Renaissance grille at the...

This dazzling 80-foot wall of gold covered with statues is considered the largest altarpiece (retablo mayor) ever made. Carved from walnut and chestnut, and blanketed by a staggering amount of gold leaf, it took three generations to complete (1481-1564). Its 44 scenes tell the story of Jesus and Mary—left to right, bottom to top. Focus on the main spine of scenes running up the center. At the bottom sits a 750-year-old silver statue of Baby Jesus and Mary—the cathedral’s patroness since Christians first worshipped here in the old converted mosque. Above Mary, find the scene of Baby Jesus (with cow and donkey) being born in a manger. Above that, Mary (flanked by winged angels) is assumed into heaven. Above that, a shirtless, flag-waving Jesus stands atop his coffin, having been resurrected. And above that, he ascends past his disciples into heaven. Bible scholars can trace the entire story through the miracles, the Passion, and the Pentecost. Look way up to the tippy-top, where a Crucifixion adorns the dizzying summit: That teeny figure is six feet tall.

Now crane your neck skyward to admire the elaborate ceiling with its intricate interlacing arches. Though done in the 16th-century Spanish Renaissance style, this stonework is only about 100 years old. You’re standing under the cathedral’s central dome, which has collapsed three times in the past 500 years.

• Don’t even think about that. Turn around and check out the...

A choir area like this one—enclosed within the cathedral for more intimate services—is where church VIPs can gather close to the high altar. Choirs are common in Spain and England, but rare in churches elsewhere. They’re called choirs because singers were also allowed here to accompany services. This one features an organ of more than 7,000 pipes (played Mon-Fri at the 10:00 Mass, Sun at the 10:00 and 13:00 Mass, not in July-Aug, free entry for worshippers). The big, spinnable book holder in the middle of the room held giant hymnals—large enough for all to chant from in an age when there weren’t enough books to go around.

• Now turn 90 degrees to the right to take in the enormous silver sunburst of the...

This gleaming silver altarpiece is meant to resemble a monstrance—that’s the ceremonial vessel that displays a communion wafer in the center. This one is gargantuan, big enough for a card-table sized wafer (and made from more than 5,000 pounds of silver looted from Mexico by Spanish conquistadores in the 16th century). Amid the gleaming silver is a colorful statue of the Virgin. In 2014, Sevilla’s celebration of La Macarena’s 50th anniversary “jubilee” culminated here, remembering when this beloved icon was granted a canonical coronation by the pope.

• From here, we’ll tour some sights going counterclockwise around the church. Head left from the Altar de Plata, pass a few chapels where people come to pray to their chosen saint, and keep going to the last chapel on the right (with the big, marble baptismal font).

This chapel (Capilla de San Antonio) holds a special place in the hearts of Sevillians. Many were baptized in the big Renaissance-era font with the delightful carved angels dancing along its base. The chapel is also special for Murillo’s tender painting of the Vision of St. Anthony (1656). The saint kneels in wonder as Baby Jesus comes down surrounded by a choir of angels. Anthony, one of Iberia’s most popular saints, is the patron saint of lost things—so people come here to pray for his help in finding jobs, car keys, and life partners. (In 1874, the cathedral had to find Anthony himself, when thieves stole this painting; it turned up in New York.) Above the Vision is The Baptism of Christ, also by Murillo. As for the stained glass, you don’t need to be an art historian to know that it dates from 1685. And by now you must know who the women are—Santa Justa and Santa Rufina, the third-century Roman sisters eaten by lions at Itálica because of their faith.

• Exiting the rear of the chapel, look for the enormous glass display case with the...

This 800-year-old battle flag shows the castle of Castile and the lion of León—the two kingdoms Ferdinand inherited, forming the nucleus of a unified, Christian Spain two centuries later. This pennant was raised here over the minaret of the mosque on November 23, 1248, as Christian forces finally expelled the Moors from Sevilla. For centuries afterward, it was paraded through the city on special days.

• Continuing on, stand at the...

Face the choir and appreciate the ornate immensity of the church. Can you see the angels trumpeting on their Cuban mahogany? Any birds? On the floor before you (breaking the smooth surface) is the gravestone of Ferdinand Columbus (Hernando Colón), Christopher’s second son. Having given the cathedral his collection of 6,000 precious books, he was rewarded with this prime burial spot. Behind you (behind an iron grille) is Murillo’s Guardian Angel pointing to the light and showing an astonished child the way.

• Continue counterclockwise, passing a massive wooden candlestick from 1560. That’s old, but there’s even older stuff here. Find a chapel (opposite the towering organ) with a big wall of statues whose centerpiece is a golden fresco of Mary and Baby Jesus.

In this gilded fresco, the Virgin delicately holds a rose while the Christ Child holds a bird. It’s some of the oldest art here (from the 1300s), even older than the cathedral itself. This chapel was once the site of the mosque’s mihrab—the horseshoe-shaped prayer niche that points toward Mecca. When Christians moved in (1248), they initially used the mosque for their church services, covering the mihrab with this Virgin. The mosque served as a church for about 120 years—until it was completely torn down and replaced by today’s cathedral. But the Virgin stayed, thanks to her beauty and her role as protector of sailors—crucial in this port city. Gaze up (above the metal gate) to find flags of all the New World countries where the Virgen de la Antigua is revered.

• Just past the Virgen de la Antigua chapel is the...

Four royal pallbearers carry the coffin of Christopher Columbus. It’s appropriate that Columbus is buried here. His 1492 voyage departed just 50 miles away, and the port of Sevilla became the exclusive entry point for all the New World plunder that made Spain rich. Columbus’ pallbearers represent the traditional kingdoms that formed the core of Spain: Castile, Aragon, León, and Navarre (identify them by their team shirts). The last kingdom, Granada, is also represented: Notice how Señor León’s pike is stabbing a pomegranate, the symbol of Granada—the last Moorish-ruled city to succumb to the Reconquista in that momentous year of 1492.

Columbus didn’t just travel a lot while alive—he even kept it up posthumously. He died in 1506 in northwestern Spain (in Valladolid) where he was also buried. His remains were then moved to a monastery here in Sevilla, then to what’s now the Dominican Republic (as he’d requested), then to Cuba. Finally—when Cuba gained independence from Spain in 1902—his remains sailed home again to Sevilla. After all that, are these really his remains? In 2006, a DNA test matched the bones of his son (buried just a few steps from here), giving Sevillians some evidence to substantiate their proud claim.

Columbus’ tomb stands, appropriately, at the church entrance reserved for pilgrims, near a 1584 mural of St. Christopher, patron saint of travelers. The clock above has been ticking since 1788.

• From here, our tour focuses on some of the artistic treasures of this rich church. For centuries, the faithful have donated their time and money to beautify their cathedral. The next chapel is the...

This space is where the priests get ready each morning before Mass. The painting above the altar is remarkable for several reasons: It’s by the well-known artist Goya, it was specifically painted for this room, and it features our old friends Justa and Rufina with their trademark bell tower, pots, and palm leaves. Here they’re bathed in a heavenly light, triumphing over a broken pagan statue, while the lion who was supposed to attack meekly licks their toes. Goya daringly portrayed the two third-century Romans dressed like fashionable women of his time.

• Two chapels farther along is the entrance to the...

Marvel at the ornate, 16th-century dome of the main room, a grand souvenir from Sevilla’s Golden Age. The intricate masonry, called Plateresque, resembles lacy silverwork (plata means “silver”). God is way up in the cupola. The three layers of figures below him show the heavenly host; relatives in purgatory—hands folded in prayer—looking to heaven in hope of help; and the wretched in hell, including naked sinners engulfed in flames and teased cruelly by pitchfork-wielding monsters.

Dominating the room is a nearly 1,000-pound, silver-plated monstrance (vessel for displaying the communion wafer). This is the monstrance used to parade the holy host through town during Corpus Christi festivities.

• The next door down leads you through a few rooms, including one with a unique oval dome.

This is the 16th-century chapter house (sala capitular), where monthly meetings take place with the bishop (he gets the throne, while the others share the bench). The paintings here are by Murillo: The Immaculate Conception (1668, high above the bishop’s throne) is one of his finest (and largest) depictions of Mary (in blue and white, standing amid a cloud of cherubs). To the right of her is Ferdinand (with sword and globe), along with more of Sevilla’s favorite saints.

• Now enter the...

This wood-paneled Room of Ornaments shows off gold and silver reliquaries, which hold hundreds of holy body parts and splinters of the true cross. The star of the collection is Spain’s most valuable crown—the Corona de la Virgen de los Reyes. Made in 1904, it sparkles with nearly 12,000 precious stones, including the world’s largest pearl—used as the torso of an angel. This amazing treasure was completely paid for by devoted locals. Not fit for a human head, once a year the crown is taken out and placed on the head of a statue of the Virgin who represents Mary as patron of this cathedral.

• Leave the treasury and continue around, passing (directly behind the high altar) the closed-to-tourists 15 Royal Chapel. Though it’s only open for worship (access from outside), it’s the holy-of-holies of Sevillian history, with the tombs of Sevilla’s founder Ferdinand III, his enlightened successor Alfonso the Wise, and Pedro I, who built the Alcázar.

In the far corner is the entry to the Giralda bell tower. It’s time for some exercise (unless you’re touring the rooftop later—then you can skip it).

Your church admission includes entry to the bell tower, a former minaret. Notice the beautiful Moorish simplicity as you climb to its top, 330 feet up (35 ramps plus 17 steps), for a grand city view. The graded ramp was designed to accommodate a donkey-riding muezzin, who clip-clopped up five times a day to give the Muslim call to prayer back when a mosque stood here. It’s less steep the farther up you go, but if you get tired along the way, stop at balconies for expansive views over the entire city.

• Back on the ground, head outside. As you cross the threshold, look up. Why is a crocodile hanging here? It’s a reminder of the live crocodile given by the Islamic sultan of Egypt (in 1260) to the Christian king Alfonso the Wise as a show of goodwill. Alfonso proudly showed his croc off, and when it died he had the body stuffed for display. When that rotted, it was replaced with this wooden replica.

You’re now in an open-air courtyard (with WCs at the far end). This is the...

This courtyard—one of the few things remaining from the original mosque—was the place for ritual ablutions. Muslims would enter through the keyhole-shaped archway, stop at the fountain to wash their hands, face, and feet, then proceed inside to pray. Another remnant is the Puerta del Perdón (“Door of Forgiveness”), the keyhole-arch entrance (and now tourist exit), with its original green doors of finely wrought bronze-covered wood. The lanes between the courtyard bricks were once irrigation streams—a reminder that the Moors introduced irrigation to Iberia. Otherwise, the Christians completely leveled the site and turned a mosque of brick into a cathedral of stone.

• The biggest remnant of the original mosque ended up becoming the symbol of Sevilla itself—the Giralda bell tower. Find a spot near the Puerta del Perdón where you can look back and take in the tower.

This was the mosque’s minaret from which Muslims were called to prayer. After the Reconquista, it still called the faithful to prayer...but as a Christian bell tower. The tower offers a brief recap of the city’s history: a strong foundation of precut blocks from ancient Rome; a middle section of brick made by the Moors; and the rebuilt tower from the Christian era (the original fell in 1356 and was rebuilt even higher in the 1550s).

Capping the tower is a 4,000-pound bronze female angel symbolizing the Triumph of Faith—specifically, the Christian faith over the Muslim one. The statue serves as a weather vane. (In Spanish, girar means “to rotate”; la giralda refers to this figure that turns with the wind.) A ribbon of letters (you can make out Nomen Die from this vantage point) proclaims, “The strongest tower is the name of God.”

Now take in the whole scene—Giralda tower, courtyard, and the church with its flying buttresses and magnificent Gothic doorways. Enjoy the impressive remnants of the former mosque and the additions of today’s church. And appreciate the significance of this site that was sacred to two great world religions.

• Your cathedral tour is finished. If you haven’t already done so, loop around the exterior of the cathedral (described at the start of the tour).

Or for a truly religious experience, consider one more stop. After exiting the cathedral, make a U-turn left onto Avenida de la Constitución. At #24 (directly across from the church door), enter the passageway marked Plaza del Cabildo, which leads into a quiet courtyard with a humble little hole-in-the-wall shop.

Here, nuns sell handicrafts (such as baptismal dresses for babies) and baked goods (Mon-Fri 10:00-13:30 & 17:00-19:30, Sat-Sun 10:30-14:00, closed Aug). You won’t actually see the cloistered sisters, since this shop is staffed by laypeople, but the pastries they make are heavenly—Sevilla’s best cookies, bar nun.

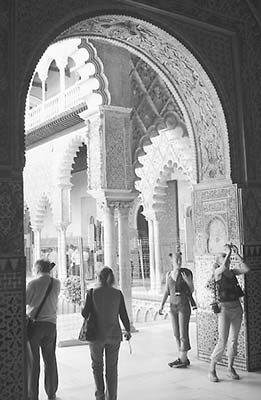

This palace has been a lavish residence for Spain’s rulers for a thousand years. Originally a 10th-century palace built for the governors of the local Moorish state, it still functions as one of the royal family’s homes—the oldest in Europe that’s still in use. The core of the palace features an extensive 14th-century rebuild, done by Muslim workmen for the Christian king, Pedro I (1334-1369). Pedro was nicknamed either “the Cruel” or “the Just,” depending on which end of his sword you were on. Pedro’s palace embraces both cultural traditions.

Today, visitors can enjoy several sections of the Royal Alcázar. Spectacularly decorated halls and courtyards have distinctive Islamic-style flourishes. Exhibits call up the era of Columbus and Spain’s New World dominance. The lush, sprawling gardens invite exploration.

Cost and Hours: €12.50, €18.50 includes worthwhile audioguide, buy tickets in advance online; open daily 9:30-19:00, Oct-March until 17:00; +34 954 502 324, www.alcazarsevilla.org. Your ticket gets you free admission to Museo de la Cerámica de Triana (see here).

Advance Tickets Recommended: You could line up for hours to buy a ticket, but why? The smart move is to buy a timed-entry ticket in advance. Book online as soon as you can, then use the short line for savvy travelers who did just that (show your printed or digital ticket).

Tours: The fast-moving audioguide gives you an hour of information as you wander. Or consider Concepción Delgado’s guided tour (see “Tours in Sevilla,” earlier).

My free Sevilla City Walk audio tour includes background information and descriptions of the Royal Alcázar exterior, but not the interior.

My free Sevilla City Walk audio tour includes background information and descriptions of the Royal Alcázar exterior, but not the interior.

Upper Royal Apartments Option (Cuarto Real Alto): With a little planning, you could fit in a visit to the 15 lavish, chandeliered, Versailles-like rooms used by today’s monarchs, including the official dining room, living rooms, and stunning Mudejar-style Audience Room. Your group (15 people max) will be escorted on a 30-minute tour while using the included audioguide. It’s a delightful and less-crowded part of the palace, but you’ll need to book well in advance (€4.50, must check bags in lockers, check in 15 minutes early, last tour departs at 13:30). With this ticket, you become an Alcázar VIP and can enter the complex any time you like that day (go to the front of the line and present ticket).

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourThis royal palace is decorated with a mix of Islamic and Christian elements—a style called Mudejar. It offers a thought-provoking glimpse of a graceful al-Andalus world that might have survived its Castilian conquerors...but didn’t. The floor plan is intentionally confusing, to make experiencing the place more exciting and surprising. While Granada’s Alhambra was built by Moors for Moorish rulers, what you see here is essentially a Christian ruler’s palace, built in the Moorish style by Moorish artisans (after the Reconquista).

• Just past the entrance, you’ll go through the garden-like Lion Patio (Patio del León), with the rough original structure of the older Moorish fortress on your left (c. 913), and through the 12th-century arch into a courtyard called the...

For centuries, this has been the main gathering place in the Alcázar (and it’s now where tourists converge). Get oriented. The palace’s main entrance is directly ahead, through the elaborately decorated facade.

History is all around you. The Alcázar was built over many centuries, with rooms and decorations from the various rulers who’ve lived here. Behind you, the courtyard you passed through has remnants of the original 10th-century Moorish palace. The towering entrance facade before you dates from after Sevilla was Christianized, when King Pedro I built the most famous part of the complex. To the right are rooms dedicated to Spain’s Golden Age, when the Alcázar was home to Ferdinand and Isabel and, later, their grandson Charles V (the most powerful man in Europe...the Holy Roman Emperor). Each successive monarch left their mark, adding still more luxury. And today’s king and queen still use the palace’s upper floor as one of their royal residences.

• Before entering the heart of the palace, let’s get a sense of its history. Start in the wing to the right of the courtyard.

In the first room, filled with big canvases, find the biggest painting (and most melodramatic). This shows the crucial turning point in the Alcázar’s history: The king who defeated the Moors in 1248, and turned the palace from Moorish to Christian, is kneeling humbly before the bishop, symbolically giving his life to God. Other paintings depict later royalty who made their mark on the Alcázar’s history. (This particular room is still used today for fancy government receptions.)

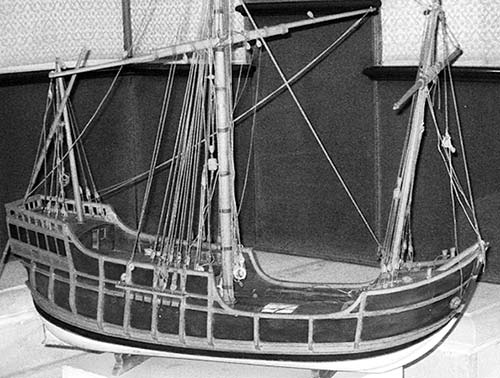

Queen Isabel put her stamp on the Alcázar by building this series of rooms (1503). Having debriefed Columbus after his New World discoveries, she realized the potential business opportunity. She created this wing to administer Spain’s New World ventures. In these halls, Columbus recounted his travels, Ferdinand Magellan planned his around-the-world cruise, and Amerigo Vespucci tried to come up with a catchy moniker for that newly discovered continent.

Continue into the pink-and-red Audience Chamber, once the Admiralty’s chapel. The altarpiece painting is St. Mary of the Navigators (Santa María de los Navegantes, Alejo Fernández, 1530s). The Virgin—the patron saint of sailors and a favorite of Columbus—keeps watch over the puny ships beneath her. Her cape seems to protect everyone under it—even the Native Americans in the dark background (the first time “Indians” were painted in Europe). Kneeling beside the Virgin (on the right, dressed in gold, almost joining his hands together in prayer) is none other than Christopher Columbus. He’s on a cloud and this is heaven (this was painted a few decades after his death). Notice that Columbus is blond. Columbus’ son said of his dad: “In his youth his hair was blond, but when he reached 30, it all turned white.” Many historians believe this to be the earliest known portrait of Columbus. If so, it’s also likely to be the most accurate. The man kneeling on the left side of the painting, with the big gold cape, is King Ferdinand.

Left of the painting is a model of Columbus’ Santa María, his flagship and the only of his three ships not to survive the 1492 voyage. Columbus complained that the Santa María—a big cargo ship, different from the sleek Niña and Pinta caravels—was too slow. On Christmas Day it ran aground off present-day Haiti and tore a hole in its hull. The ship was dismantled to build the first permanent structure in America, a fort for 39 colonists. (After Columbus left, the natives burned the fort and killed the colonists.) Opposite the altarpiece (in the center of the back wall) is the family coat of arms of Columbus’ descendants, who now live in Spain and Puerto Rico. Using Columbus’ Spanish name, it reads: “To Castile and to León, a new world was given by Colón.”

As you return to the courtyard, don’t miss the room (beyond the grand piano) with display cases of ornate fans (mostly foreign and well-described in English). A long painting (designed to be gradually rolled across a screen and viewed like a primitive movie) shows 17th-century Sevilla during Holy Week. Follow the procession, which is much like today’s, with traditional floats carried by teams of men along with a retinue of penitents.

• Back in the Courtyard of the Hunt, face the impressive entrance to the...

This is the entrance to King Pedro I’s Palace (Palacio del Rey Pedro I), the Alcázar’s 14th-century nucleus. Though it looks Islamic—with lobed arches, slender columns, and intricate stucco work—it’s a classic example of the palace’s Mudejar style. Looking closer you’ll see Christian motifs mixed in—coats of arms of Spain’s kings and heraldic animals. About two-thirds of the way up, find the inscription dedicated to the man who built the gate (center of the top row)—“Conquerador Don Pedro.” The facade’s elaborate blend of Islamic tracery and Gothic Christian elements introduces us to the unique style seen throughout Pedro’s part of the palace.

• Enter the palace. Go left through the vestibule (impressive, yes, but we’ll see better), and emerge into the big courtyard with a long pool in the center. This is the...

You’ve reached the center of King Pedro’s palace. It’s an open-air courtyard, surrounded by rooms. In the middle is a long, rectangular reflecting pool. Like the Moors who preceded him, Pedro built his palace around water.

King Pedro cruelly abandoned his wife and moved into the Alcázar with his mistress, then hired Muslim workers from Granada to re-create the romance of that city’s Alhambra in Sevilla’s stark Alcázar. The designers created a microclimate engineered for coolness: water, sunken gardens, pottery, thick walls, and darkness. This palace is considered Spain’s best example of the Mudejar style. Stucco panels with elaborate designs, coffered wooden ceilings, and intricate lobed arches atop slender columns create a refined, pleasing environment. Ceramic tiles on the walls add color. The elegant proportions and symmetry of this courtyard are a photographer’s delight.

Pedro’s original courtyard was a single story; the upper floors were added by Isabel’s grandson, Charles V, in the 16th century. Today, those upper-story rooms are part of the Spanish monarch’s living quarters. See the different styles: Mudejar below (lobed arches and elaborate tracery) and Renaissance above (round arches and less decoration).

• Let’s explore some rooms surrounding the courtyard. Start with the room at the far end of the long reflecting pool—beneath the big octagonal tower. This is the palace’s most important room.

Here, in his throne room, Pedro received guests and caroused in luxury. The room is a cube topped with a half-dome, like many important Islamic buildings. In Islam, the cube represents the earth, and the dome is the starry heavens. In Pedro’s world, the symbolism proclaimed that he controlled heaven and earth. Islamic horseshoe arches stand atop recycled columns with leafy golden capitals. As you marvel, remember that this is original, from the 1300s.

The stucco on the walls is molded with interlacing plants, geometrical shapes, and Arabic writing. Despite this being a Christian palace, the walls are inscribed with unapologetically Muslim sayings: “None but Allah conquers” and “Happiness and prosperity are benefits of Allah, who nourishes all creatures.” The artisans added propaganda phrases, such as “Dedicated to the magnificent Sultan Pedro—thanks to God!” (Perhaps the Allah quotes survived because Muslims and Christians praise the same God, and in Arabic—Muhammad’s native language—God is called Allah.)

The Mudejar style also includes Christian motifs. Find the row of kings, high up at the base of the dome, chronicling all of Castile’s rulers from the 600s to the 1600s (portrayed as if on playing cards). Within the intricate patterns inside the dome, you can see a few coats of arms—including the castle of Castile and the lion of León. These symbols (along with another royal symbol with twin columns) are seen throughout the palace. The Mudejar style also incorporates birds, seashells, and other natural objects you wouldn’t normally find in Islamic decor, as it traditionally avoids realistic images of nature.

Notice how it gets cooler as you go deeper into the palace. Straight ahead from the Hall of the Ambassadors, in the Philip II Ceiling Room (Salón del Techo de Felipe II), look above the arches to find peacocks, falcons, and other birds amid interlacing vines. Imagine day-to-day life in the palace—with VIP guests tripping on the tiny steps.

• Make your way to the second courtyard (with your back to the Hall of the Ambassadors, circle right). This smaller courtyard (with the skylight) is the...

This delicate courtyard was reserved for the king’s private family life. Originally, the center of the courtyard had a pool, cooling the residents and reflecting decorative patterns that were once brightly painted on the walls. The columns—recycled from ancient Roman and Visigothic buildings—are of alternating white, black, and pink marble. The courtyard’s name comes from the tiny doll faces found at the base of one of the arches. Circle the room and try to find them. (Hint: While just a couple of inches tall, they’re eight feet up—kitty-corner from where you entered.)

• Wander around before returning to the big Courtyard of the Maidens. In the middle of the right side an arch leads to the...

Emperor Charles V ruled Spain at its peak and, flush with New World wealth, expanded the palace. His marriage to his beloved cousin Isabella—which took place in this room—joined vast realms of Spain and Portugal. Devoutly Christian, Charles celebrated his wedding night with a midnight Mass, and later ordered the Mudejar ceiling in this room to be replaced with the less Islamic (but no less impressive) Renaissance one you see today. At the base of the ceiling, find Charles’ coat of arms—the black double eagle.

• When you’re ready to move on, return to the Courtyard of the Maidens, then turn right. In the corner, find the small staircase. Go up to rooms decorated with bright ceramic tiles and Gothic vaulting. Pass directly through the chapel (with its majestic mahogany altar on your right) and into a big, long room.

This airy banquet hall is where Charles and Isabella held their wedding reception. Note the huge coats of arms: Charles’ double eagle on one end and Isabella’s shield of Portugal on the other. Both are painted cloth from the 1500s. Tiles of yellow, blue, green, and orange (from the 16th century) line the room, some decorated with whimsical human figures with vase-like bodies. Imagine a formal occasion here, as elegant guests took in the views of the gardens. To this day, city officials and VIPs still host receptions here.

• Midhall, on the left, enter the...

Next door, the walls are hung with 18th-century Spanish copies of 16th-century Belgian tapestries showing the power, conquests, and industriousness of Charles’ prosperous reign. This series of scenes depicts the pivotal Conquest of Tunisia (1535), which stopped the Muslim Ottomans in North Africa at a time when they were threatening Europe on different fronts. (The highlights are described in Spanish along the top, and in Latin along the bottom.) The map tapestry of the Mediterranean world has south pointing up. Find Genova, Italy, on the bottom; Africa on top; Lisbon (Lisboa) on the far right; the large city of Barcelona in between; and Tunisia (Tunis). The ships of the Holy Roman Empire gather in anticipation of a major battle. The artist included himself (far right) holding the legend—with a scale in both leagues and miles.

At the far end of the room is a big, dramatic portrayal of the Spanish Navy. With cannon-laden warships and a merchant fleet to haul goods and people, Spain ruled the waves—and thereby an empire upon which the sun never set. Its reign lasted from 1492 until the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588; after that, Britannia’s navy took the helm, and it was her crown that controlled the next global empire.

• Return to the Banquet Hall, then head outside at the far end to the extensive landscaped gardens. First up is the...

The Mercury Pond is marked by a tiny bronze statue of the messenger of the gods, with his cute little winged feet. This was a reservoir fed by a 16th-century aqueduct that irrigated the palace’s entire garden. As only elites had running water, the fountain was an extravagant show of power. The long stucco-studded wall along one side of the garden was part of the original Moorish castle wall. In the early 1600s, when fortifications were no longer needed here, that end was redesigned to be a grotto-style gallery.

• From the Mercury Pond, steps lead into the formal gardens. Just past the bottom of the steps, a tunnel on the right leads under the palace to the coolest spot in the city—the Baths of María de Padilla. This long underground pool was a rainwater cistern, named for Pedro of Castile’s mistress who frequented the place. Its mysterious medieval atmosphere is like something out of Game of Thrones—which actually did use this and other Alcázar settings in several episodes of the television series. Finally, explore the rest of the...

The intimate geometric zone nearest the palace is the Moorish garden. The far-flung garden beyond that was the backyard of the Christian ruler.

Here in the gardens, as in the rest of the palace, Christian and Islamic traditions merge and mingle. Both cultures used water and nature as essential parts of their architecture. The garden’s pavilions and fountains only enhance this. Wander among palm trees, myrtle hedges, and fragrant roses. While tourists pay to be here, this is actually a public garden, and free to locals. It’s been that way since 1931, when the king was exiled and Spanish citizens took ownership of royal holdings. In 1975, the Spanish people allowed the king back on the throne—but on their terms...which included keeping this garden.

From the Moors to Pedro I to Ferdinand and Isabel, and from Charles V to King Felipe VI, we’ve seen the home of a millennium of Spanish kings and queens. Feel free to explore the exotic landscape they created and create your own Arabian Nights fantasies.

• Your Alcázar tour is over. When you’re ready to leave these gardens, return to the Mercury Pond and step back into the palace into a small courtyard with palm trees. From here, consider your options:

Just a few steps away, on the other side of the stucco wall, is a massive bougainvillea and a 12 bigger garden with cafeteria and WCs. Once a farm that provided for the royal community, the garden is now home to a cool and convenient cafeteria with a delightful terrace.

If you’ve booked a spot to visit the 13 Upper Royal Apartments, return to the Courtyard of the Hunt, and head upstairs.

Otherwise, follow 14 exit signs and head out through the Patio de Banderas, once the entrance for guests arriving by horse carriage. Enjoy a classic Giralda bell tower view as you leave.

To the right of the Alcázar’s main entrance, the Archivo General de Indias houses historic papers related to Spain’s overseas territories. Its four miles of shelving contain 80 million pages documenting a once-mighty empire. While little of interest is actually on show, a visit is free, easy, and gives you a look at the Lonja Palace, one of the finest Renaissance edifices in Spain. Designed by royal architect Juan de Herrera, the principal designer of El Escorial, the building evokes the greatness of the Spanish empire at its peak (c. 1600).

Download my free Sevilla City Walk audio tour for background on the Archivo General de Indias.

Download my free Sevilla City Walk audio tour for background on the Archivo General de Indias.

Cost and Hours: Free, Tue-Sat 9:30-17:00, Sun 10:00-14:00, closed Mon, Avenida de la Constitución 3, +34 954 500 528.

Background: In the early 1500s, as exotic goods began pouring into Sevilla from newly discovered lands, this spot between the cathedral and the Alcázar was an open-air market, where businessmen met to trade. Sevilla was the only port licensed to trade with the New World, and merchants came here from across Europe, establishing the city as a commercial powerhouse. The area evolved as a hub of Spanish power, where the royal palace, business community, and cathedral all came together.

In 1583, this grand building was built as a place for those merchants, moneychangers, and accountants to do their business—an early stock market, or lonja. (On the cathedral-facing side of the building stands a stone cross where businessmen would “swear to God” to be honest in their trade.) Mapmakers, sea captains, and navigators also gathered here, as well as lawyers, accountants, and politicians who could administer Spain’s far-flung colonies. Herrera designed a no-nonsense Renaissance building of symmetrical doors and windows, balustrades, and distinctive rooftop pinnacles.

By 1785, with Sevilla in decline (a victim of plagues, a silted-up harbor, and the rise of Cádiz as Spain’s main port), the building was put to new use as an archive: the storehouse for documents the country was quickly amassing from its discovery, conquest, and administration of the New World.

Visiting the Archives: The ground floor houses a small rotating exhibit that tells the story of the building. You may see copies of famous documents here, like the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494, when Spain and Portugal divvied up the New World) or the Capitulations of Santa Fe (the contract Columbus signed with Ferdinand and Isabel for his 1492 voyage). There’s often a cannon discovered by American treasure hunter Mel Fisher. He used information in the archives to find a Spanish galleon that sank off the Florida coast in 1616—with a huge treasure onboard. Fisher returned the cannon as a gesture of goodwill.

Upstairs (up an extravagant marble staircase) there are several exhibits clustered near the landing: Don’t miss the huge 16th-century security chest—meant to store gold and important documents. Its elaborate locking mechanism (it fills the inner lid) could be opened only by following a set series of pushes, pulls, and twists—an effective way to keep prying eyes and greedy fingers from its valuable contents. Portraits depict some of the explorers whose discoveries made this building possible (Columbus, Cortés, et al.), scholars who archived the documents, and the powdered-wig administrators (teniente general) of the colonial empire. Nearby, find a curtained room with an interesting 15-minute video on Sevilla’s New World connections and the archive’s work. Then browse the wooden racks with (copies of) documents from the collection. The collection covers both “Indies”—East and West—so you’ll see maps of Guatemala and the Philippines, maps by Amerigo Vespucci (who sailed from Sevilla in the 1490s and was one of the first to realize America wasn’t India), manuscripts about Magellan’s around-the-world voyage, Pizarro’s conquest of Peru, and old sketches of Indian natives.

Finally, make a big circle around the rest of the (mostly empty) upstairs to check out the rows and rows of cedar and mahogany bookshelves, beautifully decorated domes, and occasional rotating exhibits.