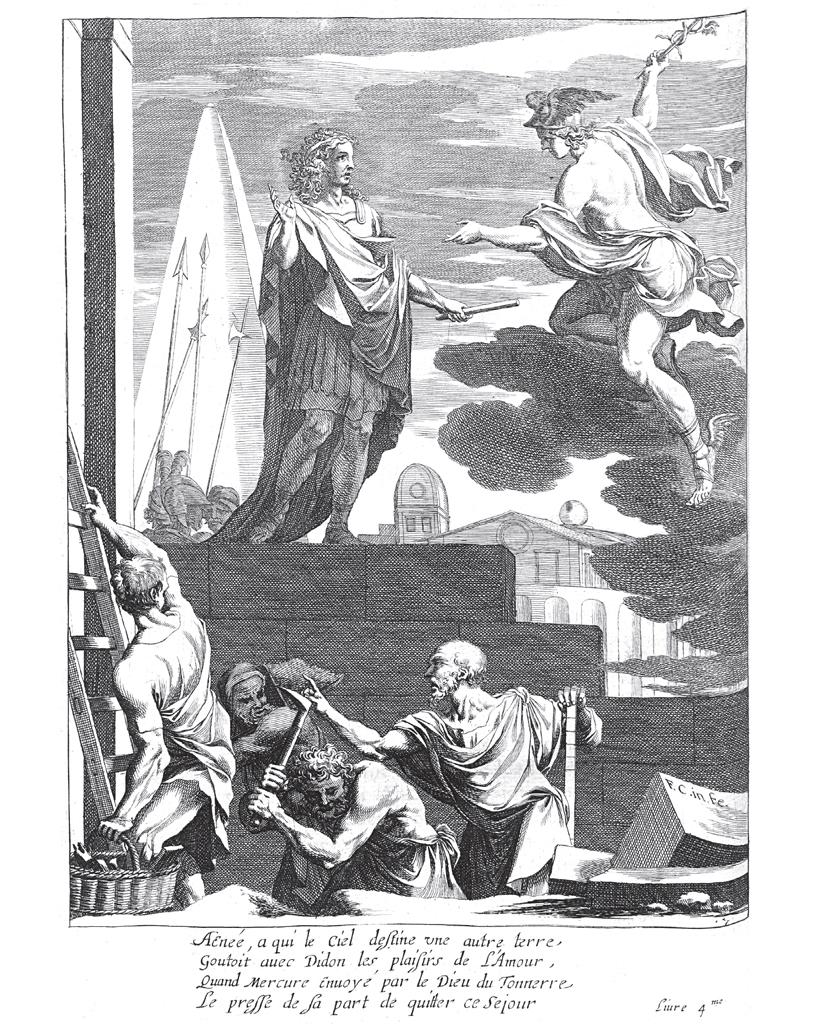

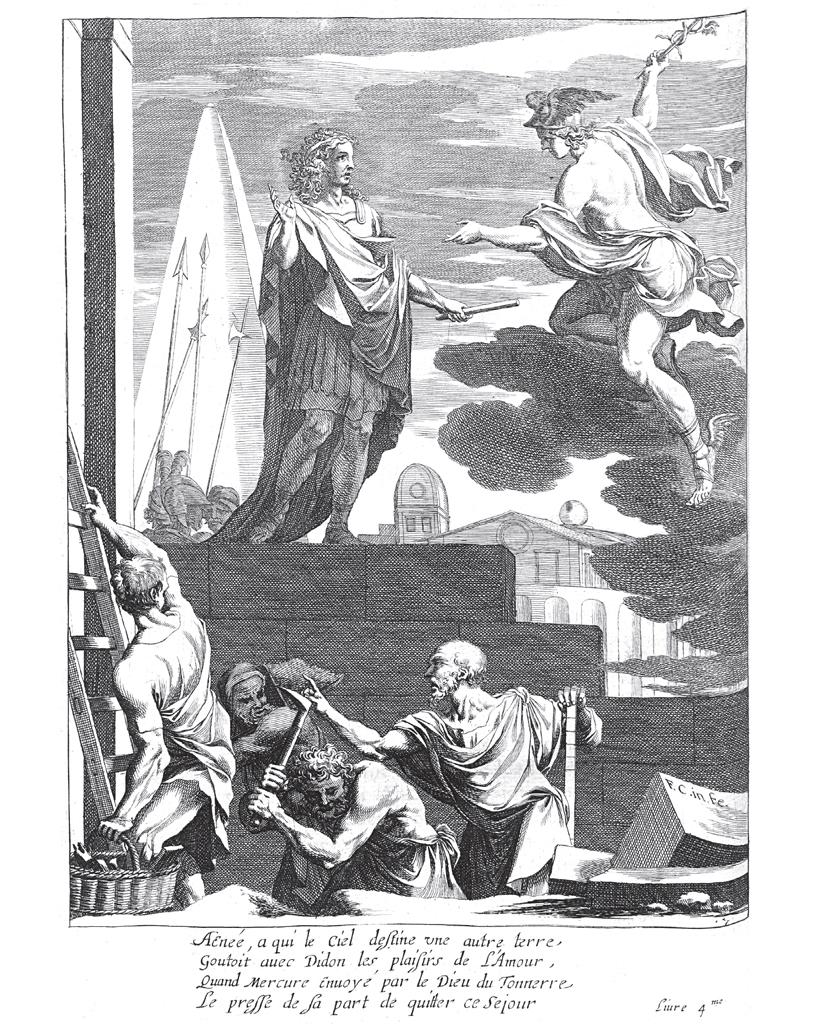

Fig. 5. Mercury descends to Aeneas in Carthage. Engraving by François Chauveau, from Michel de Marolles, Les Oeuvres de Virgile traduites en prose (Paris, 1649).

Women in the Aeneid are difficult to read. The first woman that Aeneas meets in Book 1, shortly after landing on the shore of Carthage, is not what she seems: so far from being a mortal virgin huntress she turns out to be the goddess of love, his own mother Venus. The contrast between the realm of Diana, the virgin goddess of hunting, and the realm of Venus, and the transition from one to the other, is programmatic for the further plot of the Aeneid, and it is a contrast frequently explored in the reception of the Aeneid. The disguised Venus tells her son the previous history of Dido, the new ruler of the land. When Aeneas meets Dido herself in the temple of Juno in Carthage, he is again involved in a process of judging appearances. Just before Dido’s entry Aeneas is looking at the last of a series of paintings of the Trojan War in the temple, the striking image of the Amazon warrior Penthesilea, a woman in the male world of war. An after-image superimposes itself on his first sight of the flesh-and-blood Dido, a woman playing the male role of founder and ruler of a city. We might say that Aeneas’ gaze on Dido retrospectively triggers a reception of the painting of Penthesilea, as Aeneas, and we the readers, see in a new light a figure whom Aeneas, as a participant himself in the Trojan War, had at the first viewing recognized simply as the Amazon queen he had known at Troy. And we might guess that Dido herself had chosen to include this scene in the selection of episodes from the Trojan War in her new temple of Juno because she herself identified with Penthesilea when she was unexpectedly thrust into the role of leader of her people. There follows a famous simile comparing Dido to Diana amidst her nymphs (1.498–502). This reminds the reader of the previous apparition of the disguised Venus, mistaken by Aeneas for Diana or one of Diana’s nymphs, and it is an easy conclusion that the Diana simile is focalized through the eyes of the character Aeneas. The resulting series of female figures – Venus (in the likeness of Diana) – Penthesilea – Dido (in the likeness of Diana) – is seen through the eyes of a character, Aeneas, who functions as an interpreter or reader within the text, and it prompts the reader of the Aeneid to further interpretations of the woman whose story this is, Dido.

These models within the text ask the reader to gauge how far Dido really is like Diana or Venus or Penthesilea. The intratextual models are multiplied by the intertextual models, allusions to characters in other texts. All of the characters in the densely allusive work that is the Aeneid, an epic consciously drawing on the whole of the previous Greco-Roman literary tradition, are built up with traits from a plurality of earlier literary – and in some cases historical – characters, but Dido is probably the most allusively complex of them all, bearing traces of female characters in previous epic, tragedy and other genres. Dido is Virgil’s most ‘intertextual heroine’, to use a phrase of Stephen Hinds.2 An awareness of the intertextual density of Dido complicates our response to her actions and sufferings, and it also encourages the forward projection of this intertextuality on to rewritings of Dido in other characters. Once again, Virgil almost seems to inaugurate the reception of his own text.

The question of how to perceive, and what to say about, Dido (and Aeneas) is embodied within the text in the monstrous personification of Fama, ‘Rumour’, who spreads a slanderous version of the love affair of Dido and Aeneas after their union in the cave. Fama in Latin can also mean poetic or historical ‘tradition’, and the personification is also an embodiment of the vagaries of reception and tradition. The indirect speech reporting the content of what Fama puts about (4.191–4) is the first retelling of the narrator’s own prior account, and so the first instance of the story’s reception. It is as if Virgil knowingly builds into his Dido narrative a prophecy of the long history of re-readings and rewritings that it would stimulate. An awareness of what is said about Dido is insistent elsewhere in Aeneid 1 and 4, on the part both of Dido and of other characters, and the Virgilian text’s own concern with Fama reverberates through the whole of the later tradition. The enduring fame of the story is described by Macrobius in terms that allude to the operations of Virgil’s own Fama in Book 4 (Saturnalia 5.17.5–6):

The story of the wanton Dido, which the world knows is false, has for so many ages maintained the appearance of truth and so flits about on the lips of men as if it were true, that painters and sculptors and weavers of tapestries use this above all in fashioning their images […] and it is no less celebrated in the gestures and songs of actors. The story’s beauty has had such power that though everyone knows of the Phoenician queen’s chastity and is aware that she took her own life to avoid the loss of her honour, they connive at the fable, suppress their belief in the true story, and prefer to celebrate as true the sweetness instilled in human hearts by the fiction.

Macrobius here refers to the particular scandal of the Virgilian story of Dido, the fact that it is in conflict with an older version according to which Aeneas never came to Carthage (legendary chronology makes it impossible). In this version, when she had founded Carthage, Dido, faithful to her first husband Sychaeus, who had been murdered in her home city of Tyre by her wicked brother Pygmalion, committed suicide in order to avoid marrying her African suitor Iarbas. It is possible that the version in which Dido falls in love with Aeneas had already been told in Naevius’ Bellum Punicum, an earlier Roman epic on the First Punic War between Rome and Carthage of which only a few fragments survive. Nevertheless the prominence given to fama, with both a capital and a lower-case f, in Aeneid 4 betrays an awareness that Virgil’s account of Dido is a mixture of truth and falsehood, if by ‘truth’ is understood the earlier version found in the historians.3 Virgil himself may stand accused of slandering the chaste and virtuous Dido. Mercury’s shocking words on the fickleness of women, spoken in order to jolt Aeneas into leaving Dido, ‘woman is an inconstant and changeable thing’ (4.569–70 uarium et mutabile semper | femina) could more justly be applied to poetic tradition, reception, Fama, whose person and utterances are notoriously shifting and changeable.

The defence of Dido against Virgil becomes something of a commonplace. An anonymous Greek epigram ‘On a painting of Dido’ (Greek Anthology 16.151) puts words in Dido’s mouth: ‘I was just like this image, but I did not have the character that you hear about, having gained glory rather for reputable behavior. I never set eyes on Aeneas, nor did I come to Libya at the time of the sack of Troy […] Muses, why did you arm chaste Virgil against me to tell lies against my virtue?’ The sixteenth-century Italian humanist Sperone Speroni has a different slant on it in his Discourses on Virgil, making out that the historical impossibility of the episode is consciously used by Virgil to warn against Rumour, which would call Aeneas ‘treacherous’ and Dido ‘unchaste’. In the Spanish Golden-Age playwright Gabriel Lobo Lasso de la Vega’s Tragedy on the Restored Honour of Dido, Fama appears for the first time in the epilogue to proclaim the honour of the queen and to denounce Virgil’s false accusations against her, so inverting the role of Fama in Aeneid 4.

The ‘two Didos’ approach has a long history.4 The Church Fathers, including Tertullian and Jerome, used the chaste Dido as an example in urging women to observe virginity or at least not to marry for a second time.5 Jerome alludes to St Paul’s advice that ‘If they cannot contain, let them marry: for it is better to marry than to burn’ (1 Corinthians 7:9), when he praises Dido for ‘preferring to burn rather than marry’ (Against Jovinian 1). Of the ‘three Florentine crowns’ of early Renaissance Italian literature, Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio, Dante places Dido, who killed herself for love and was unfaithful to the ashes of Sychaeus, in the circle of the lustful in Inferno, between the Babylonian queen Semiramis and Cleopatra (Inferno 5.61–2). But the other two ‘crowns’, Petrarch and Boccaccio, were central in propagating the chaste Dido. In the Trionfi Petrarch awards Dido a place in the Triumph of Chastity (155–9), for ‘wishing to meet her end for her beloved and faithful husband, not for Aeneas […] Dido, driven to death by love of honour, not idle love, as the popular rumour has it’. ‘Popular rumour’ (‘publico grido’) is a nod in the direction of Virgil’s Fama, who spreads the report of Dido’s love affair with Aeneas. In Petrarch’s Latin epic the Africa, the African bard who sings of the chaste Dido concludes with an indignant reflection on the damage that would be done to Dido’s name if someone overconfident in his own wit were to traduce the queen by writing of an illicit love affair. This is another arch allusion to the version of Virgil, a poet who has not been born at the time of the events narrated in the Africa.

In his Italian works Boccaccio consistently recycles the Virgilian version of Dido’s story, but retails the historical, chaste, Dido in his Latin works: the Genealogy of the Gods, a standard Renaissance handbook of classical mythology; On Famous Women; and On the Falls of Famous Men (De casibus virorum illustrium).6 The last two works were very influential in fourteenth-and fifteenth-century vernacular literature: both were translated into French, and the latter, from the French translation, into English by John Lydgate as The Fall of Princes. In On Famous Women (Ch. 42) Boccaccio draws on the ancient tradition in his praise of Dido for ‘putting aside womanly weakness and resolving on a masculine strength of mind’. Boccaccio appeals to the claim (going back to Servius) that in Punic ‘Dido’ means ‘virago’. This is also the Virgilian Dido, but only up to the point at which she meets Aeneas: ‘a woman was leader of the undertaking’, as Venus describes the Dido who led her followers into exile (Aen. 1.364 dux femina facti), where dux, a word usually used of male leaders, is strikingly juxtaposed with femina. Boccaccio then veers into the kind of praise showered on the chaste Dido by the Church Fathers: ‘O unsullied glory of chastity! O venerable and everlasting specimen of unbowed widowhood, Dido! I could wish that all widows might gaze on you, and that Christian women above all should look on your resolve.’ The chaste Dido has a lot in common with Lucretia, the faithful wife who committed suicide to prove her innocence after being raped by the son of Tarquin the Proud, the last king of Rome. The two are paired as examples of unbending chastity from Tertullian onwards. Indeed it is arguable that traces of the chaste Dido are still visible in the fallen Virgilian character, in her lament, too late, over the loss of her sense of shame and of her reputation, and in the manner of her death. The parallels between the two stories are picked up in a long line of ‘contaminations’ of the Virgilian narrative with the history of Lucretia.7

The opposition of the chaste and the unchaste Didos is not the only duality in her story. In Virgil she starts out as the welcoming host (hospes) in whom Aeneas recognizes his double as a civilized and compassionate leader of men, but she turns into Aeneas’ implacable enemy (hostis), whose dying curse will, in the fullness of time, summon up the avenger Hannibal, Rome’s Carthaginian mortal enemy. Carthage post-Aeneid 4 is the dangerous Other of Rome, as later still another north African kingdom, Cleopatra’s Egypt, will be the enemy Other of Octavian’s Rome, conveniently for propaganda purposes. The story of Dido and Aeneas is an aetiology of the ethnic polarization of Rome and Carthage; the point of national differentiation is also the point at which the beautiful Dido metamorphoses into a terrifying Fury, as she promises Aeneas that after her death she will pursue him with the black torches of the Furies, present everywhere as a threatening shade (Aen. 4.384–6). Silius Italicus finds the narrative impetus for his own highly Virgilian epic on the war between Hannibal and Rome in a shrine dedicated at the heart of Carthage to the shade of Dido. Here the boy Hannibal swears an oath by the ghost of Dido to pursue the Romans with iron and fire, by land and sea, when he grows up (Punica 1.114–15). Sequar ‘I will pursue’ is the verb used by Dido first in her threat to Aeneas that ‘When I am gone I will pursue you with black flames’, and again in her curse, when she calls for an avenger to arise from her bones to pursue the Trojans with torch and iron (Aen. 4.625–6). The shrine of Dido is a portal through which the forces of Hell are summoned into the world above: as Hannibal’s oath revives the terms of Dido’s curse, he himself becomes the embodiment of Dido’s fury.

Virgil develops the contrast between welcoming queen and avenging Fury, between like-minded friend of the Trojans and implacable foreign foe of the Romans, with subtlety and psychological plausibility. The transformation of beautiful woman into monstrous Fury will become a schematic contrast between fair and foul in Christianizing constructions of the feminine.

There have also been positive appropriations of Dido’s ethnicity. The Church Father Tertullian, who was born in or near Carthage, may have championed the chaste Dido partly out of African pride.8 She is of course herself not a native African, but a Phoenician exile from the city of Tyre in Lebanon. Virgil makes little of her semitic origins, although he is aware of the Punic etymologies of her name, Dido (‘wanderer’) and of the name of her city Carthage (‘new city’, Kart Hadasht).9 Juno, who has ambitions for Carthage to rule the world, was syncretized in antiquity with the Punic goddess Tanit. Punic colouring is introduced in one of the several novelistic handlings of Dido’s story, David MacNaughton’s Dido. A Love Story (London, 1977), a retelling of the story-line of Aeneid 1–4 in the mouth of Ascanius, with the twist that Dido has passionate and prolonged sex with Ascanius before succumbing to her passion for his father Aeneas. Aeneas himself is revealed to be half-Phoenician, the son of Anchises by a Phoenician priestess of Aphrodite (assimilated to the Phoenician Astarte) from Paphos in Cyprus. In the novel Dido’s sister Anna teaches Ascanius some Punic, and there is some exotic religious colouring in the identification of the Virgilian Juno with the Punic goddess Asherat (rather than Tanit).

Unsurprisingly, ancient Carthage, now a suburb of Tunis, figures in the works of some modern Tunisian writers.10 A more pan-African slant informs ‘L’Élégie de Carthage’ (1975) by the Senegalese poet, and first president of Senegal, Léopold Sédar Senghor, who also coined the word ‘négritude’, the label for a francophone black movement that rejected French colonial racism. ‘L’Élégie’ is dedicated to Habib Bourguiba, the first president of Tunisia. In the second ‘Chant’ the poet weeps over Dido with tears of pride and regret, very unlike the tears shed for Dido for which Augustine reproached himself (see p. 135). Part of the regret springs from the cause for Dido’s own tears:

You cried for your white god, his golden helmet on his crimson lips,

And you cried wonderfully for Aeneas in evergreen scents.

His eyes of Northern Lights, the April snow in his speckled beard.

What had you asked so faithfully of the black Woman.

The Great Priestess of Tanit, color of night?

She listens to the distant sources of rivers in the shadowy woods,

To all the heartbeats of Africa. She would have reminded you of Iarbas,

Son of Garamantia [Dido’s African suitor].

In the third ‘Chant’ the poet weeps over Dido’s inheritor Hannibal, who was ‘so close to overthrowing | The forces of the north’.11

When we first catch sight of Dido’s new city of Carthage in the Aeneid it seems indistinguishable from other Hellenistic – or Roman – cities around the Mediterranean, with properly functioning political institutions and public buildings. And, like an Alexandria or a Rome, Carthage is a city of wealth and luxury. Ancient moralists often characterize the luxury endemic to an advanced urban civilization as infection by the vices of the Other, and in particular, in classical antiquity, by the decadence and effeminism of the Orient. Dido’s extravagant royal banquet at Aeneid 1.697–756 is modelled on the palace and banquet of Alcinous, king of the hyper-civilized Phaeacians in Books 7 and 8 of the Odyssey. The Phaeacian lifestyle was taken by some ancient commentators hostile to Epicureanism as an image of a crude hedonism, and Virgil may hint at this. The luxury of Dido’s palace is painted in more lurid colours by the Neronian epic poet Lucan in the banquet at which the Egyptian queen Cleopatra receives Aeneas’ descendant Julius Caesar in Book 10 of the Civil War. Lucan’s Cleopatra is a rewriting of Virgil’s Dido, but Virgil’s Dido already alludes to the oriental queen demonized in Augustan propaganda as a mortal enemy of the Roman state, who had had an affair with Aeneas’ descendant Julius Caesar, and who seduced Mark Antony from his duties as a Roman statesman and general.

Dido and Cleopatra continue to be twinned in the later reception. Shakespeare’s Mark Antony famously misremembers – or wishfully rewrites – the end of the Virgilian story when he addresses the dead Cleopatra (Antony and Cleopatra 4.14.58–62): ‘Stay for me: | Where souls do couch on flowers, we’ll hand in hand, | And with our sprightly port make the ghosts gaze: | Dido and her Aeneas shall want troops, | And all the haunt be ours.’12 The French tragedian Robert Garnier in his Marc Antoine (1578; translated in English as Antonius by Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke in 1592) puts into the mouth of the dying Cleopatra a close adaptation of the dying Dido’s words in the Aeneid (4.653–8): each woman says that she could have been happy had, respectively, the Roman and the Trojan ships not come to their shore. Dryden pairs the two tales in his rewriting of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, All for Love, Prologue 8–9: ‘And [the poet] brings a tale which often has been told: | As sad as Dido’s, and almost as old.’

The night of Dido’s banquet in Aeneid 1 is also the night in which Dido falls hopelessly in love with Aeneas. In the moralizing tradition luxury and lust are constantly paired. Given Dido’s struggle with her own emotions and her wish to remain loyal to her dead husband, and given also Virgil’s notorious reticence on the subject of Aeneas’ feelings for Dido, it is one of the injustices, or at least ironies, of the reception of the Virgilian Dido that Aeneas’ diversion from his mission to travel to Italy and lay the foundations for the future Roman race often becomes the basis for narratives of the seduction of the hero by an alluring temptress, or of the hero’s surrender to the pleasures of the flesh.13 In so far as we can judge of the Virgilian Aeneas’ motives, Carthage seems to offer rather a welcome break from wandering and hardship, and possibly the prospect of a successful nation-building union of Trojans and Carthaginians.

In a persistent late-antique and medieval allegorization of the story of Aeneas according to the ages of man, Book 4 represents youth’s susceptibility to lust. In the late fifth-century Exposition of the Content of Virgil (see also Chapter 4, pp. 87–8) the shade of Virgil tells Fulgentius that in Aeneid 4 Aeneas:

on holiday from the judgement of his father goes out hunting and is scorched by love, and driven by storm and cloud, as if in mental turmoil, commits adultery. Having lingered long in this, at the prompting of Mercury he abandons a love that he entered on to evil ends because of his lust. Mercury is introduced as the god of intellect; thus at the prompting of intellect youth abandons the territory of love. This love dies of neglect, and burned out it turns to ashes.

The twelfth-century Bernardus Silvestris develops a physiological allegory of the provocation of carnal desire by an excess of food and drink in his reading of Aeneid 4: ‘he is driven to the cave by storm and rain, in other words he is led to carnal uncleanliness by the disturbances of the flesh and by the abundance of moisture deriving from excess of food and drink.’ Petrarch, who elsewhere subscribes to the version of the chaste Dido, applies an allegorical reading to the Virgilian narrative in his Letters of Old Age 4.5, an important document of early Renaissance allegorism. Here the initial temptation of the fleshly pleasure is located in Aeneas’ meeting with his disguised mother in Book 1: ‘Venus meeting Aeneas in the middle of the wood is pleasure itself […] with the appearance and dress of a virgin, to deceive the unwary. For if one were to see pleasure in its true shape, one would doubtless flee terrified by the mere sight of it; for as there is nothing more enticing than pleasure, there is nothing more foul.’14 Petrarch understands that within the narrative economy of the Aeneid Aeneas’ encounter with Venus in disguise foreshadows his first sight of Dido, a vision of female beauty eroticized through the filter of the virginal unattainability of an Amazon and the goddess Diana, but a woman made all too attainable through the force-majeure of Venus.

Petrarch’s misogynistic contrast between fair and foul is the product of a puritanical rejection of the world and the flesh that goes back to Augustine’s self-flagellation for the tears that he shed for Dido when first he learned to read (Conf. 1.13.21–2). Yet a ‘two faces of Dido’ reading is not a total distortion of the Virgilian narrative, in which the beautiful Dido will be transformed into a raging Fury. Even before that the Carthaginian queen, quasi-virginal at her first appearance, has already metamorphosed into the destructive witch. These are the two faces of Medea, an important model for Virgil’s Dido, innocent virginal princess and also powerful witch, and ultimately pitiless murderer of her own children. In classical mythology the sea-monster Scylla appears as a sharp contrast of fair and foul, maiden and monster, in Virgil’s description: ‘she has a human face and as far as the groin she is a girl with lovely breasts, but below she is a monstrous sea creature’(Aen. 3.426–7). Ovid combines other fragments of Virgil in his description of Scylla in the Metamorphoses: ‘her dark womb is girdled with fierce dogs; she has the face of a maiden and, if the poets have not invented everything, she was at one time a maiden’ (13.732–4). Line 732 is modelled on Virgil’s description of Scylla in Eclogue 6, but lines 733–4 echo the language used of the disguise of Venus in the Carthaginian woods in Aeneid 1 (315), ‘bearing the face and dress of a maiden, and the weapons of a maiden’. Ovid’s allusion to Virgil hints that the fair maiden Scylla was turned into a homicidal monster, just as the jilted Dido had been driven by anger to call down destruction against the Trojans.

The fair and foul cliché has a long history as a warning of the danger of succumbing to the temptation of female beauty. In the epic tradition the archetypal seductress is Circe, who detains Odysseus for a year on her island.15 The Homeric Circe, a dangerous but relatively sympathetic character, was later allegorized as lust, and her power to change men into beasts was interpreted as the figurative bestialization of human beings through surrender to bodily desires. Circe, together with the other goddess who detains Odysseus, Calypso, is among the models for Dido, and in Fama’s distorted report of Dido and Aeneas as slaves to luxury and lust (Aen. 4.193–4) Virgil registers the moralizing tradition of Homer interpretation. In the Renaissance epic romances of Ariosto, Torquato Tasso and Edmund Spenser, elements of both Circe and Dido are incorporated in the temptresses who detain the hero from their heroic goal, respectively Alcina, Armida and Acrasia. For example, Armida’s curse on Rinaldo in Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (16.57–60) before she swoons is modelled on Dido’s curse against Aeneas. In Spenser’s The Faerie Queene the approach of Atin, an agent of ‘strife and cruel fight’, to stir Cymochles, a personification of concupiscence, from his immersion in the delights of Acrasia’s Bower of Bliss, is modelled on Mercury’s approach to Aeneas in Carthage to shock him into recollection of his epic mission (II.v.35–8) (Fig. 5).

Dido appears in many reflections and transformations in Spenser’s The Faerie Queene.16 The first canto shuffles a number of the inaugural events of Aeneid 1 and 4. The hero, the Red Cross Knight, is overtaken by a storm, but on land not sea, and takes refuge with his companion, the beautiful Una, in a dark wood, where he encounters a monstrous female. Error, half-woman, half-serpent, shares with the Virgilian Venus-in-disguise the feature of hybridity. Error is the first of the series of female epiphanies that punctuate the poem, in her hideous fertility a negative version of the series of Venus-uirgo apparitions of beauty. Spenser’s Error is all foul, in the terms of Petrarch Letters of Old Age 4.5 the true face of Venus. Taking shelter in a storm with a woman also replicates Aeneas’ less innocent encounter in the wilds with a woman, Dido, in the storm in Aeneid 4. But nothing untoward happens between the Red Cross Knight and Una. The Dido model continues to play in inverted form when, through the magic trickery of Archimago, Red Cross is made to abandon Una. But for this hero, unlike for Aeneas abandoning Dido, this is to abandon his true path, and to devote himself to the service of Duessa, who in truth is the temptress Dido figure.17 The fair Duessa will eventually be revealed for the hideous hag that she really is, just as in Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso Alcina is unmasked as a hideous crone (7.72–4).

Visions of virginal beauty in The Faerie Queene are so many reflections of the virgin queen Elizabeth I. In his Letter to Sir Walter Raleigh Spenser identifies Elizabeth in her person of ‘a most royal queen or empress’ with Gloriana, the Fairy Queen herself who never appears in person in the six books that Spenser wrote; in her person of ‘a most virtuous and beautiful lady’ Elizabeth is identified with Belphoebe, the unattainable maiden of the woods. The relationship within The Faerie Queene between the virgin huntress Belphoebe and Queen Gloriana mirrors that between Virgil’s Venus disguised as virgin and huntress and Queen Dido. Aeneas’ response to the apparition of female beauty in the woods of Carthage, ‘O what should I call you, maiden? O, a goddess to be sure’ (1.327–8 o quam te memorem, uirgo? […] o dea certe) is echoed on a number of occasions by Spenser, most circumstantially in the appearance in the forest to Trompart and Braggadocchio of Belphoebe (Faerie Queene II.iii.21–42). Trompart opens his address with the words ‘O Goddess, (for such I thee take to be)’. Two stanzas earlier the narrator has made his own comparisons, in a double simile likening Belphoebe to ‘Diana by the sandy shore | Of swift Eurotas […] Or as that famous Queen | Of Amazons, whom Pyrrhus did destroy’, i.e. Penthesilea. These are, in reverse order, the images that frame Aeneas’ first sight of Dido in Aeneid 1, the painting of Penthesilea and the Diana simile. Spenser’s association of these three, Penthesilea, Dido, Diana, with a version of the disguised Venus earlier in Aeneid 1 acknowledges the close interconnection of all four. The further connection with Elizabeth is reinforced by the use of the Virgilian tags o quam te memorem, uirgo? and o dea certe as emblems for the two shepherds at the end of the fourth, ‘Aprill’, eclogue in Spenser’s earlier book of pastoral poetry, The Shepheardes Calender. The emblems footnote the fact that the apparition of the Virgilian Venus is a subtext for Colin Clout’s ‘lay of fair Elisa’, in which Elisa/Elizabeth also takes the role of the child of Virgil’s fourth Eclogue. Spenser thus praises the queen with reference to two Virgilian epiphanies, the miraculous boy of Eclogue 4 and the appearance of Venus in Aeneid 1.

Fig. 5. Mercury descends to Aeneas in Carthage. Engraving by François Chauveau, from Michel de Marolles, Les Oeuvres de Virgile traduites en prose (Paris, 1649).

The near identity of Dido’s other Virgilian name Elissa with the short form of Elizabeth, Eliz/sa, encouraged further allusion to Dido in the literary and artistic packaging of the English queen.18 The problems that arose through Dido’s ‘marriage’ with a foreign prince could be used as a conveniently indirect way of raising the delicate issue of whether Elizabeth should look for a husband or not. Panegyric and diplomacy are both involved in a neo-Latin drama Dido, written by the prominent university dramatist William Gager, and performed with lavish staging and musical accompaniment in the hall of Christ Church, Oxford, in June 1583 in honour of the Polish prince Albertus Alasco; this was in response to Queen Elizabeth’s request to the Earl of Leicester to provide lodging and entertainment in Oxford for the prince.19 This was two years after Elizabeth ceased to play the ‘engagement game’ with the Duke of Alençon. Gager’s play is largely a close adaptation of Virgil’s hexameters into dramatic trimeters, with some additions. A ‘Hymn to Aeneas’ in the mouth of Dido’s court-bard Iopas, is transparently designed as praise of Elizabeth’s distinguished visitor Albertus. Iopas reminds Aeneas/Albertus that however great he is, nevertheless Elisa is greater, for ‘The world sees nothing similar, or even second in place, to our Elisa’. The moralizing Epilogue opines that ‘foreign marriages rarely turn out well’, and concludes with extravagant praise of Elizabeth, trustworthy in foreign relations. Confident that ‘our Elisa’ will not succumb to an Aeneas, Gager can safely put in her mouth, in praise of Albertus, the words with which Dido had expressed her admiration – and infatuation – for Aeneas.

A series of nine scenes from the Virgilian story of Dido and Aeneas, from Aeneas’ flight from Troy to Dido’s suicide and the Trojans’ departure from Troy, appears on a pillar behind and to the left of the figure of Elizabeth in the ‘Sieve’ portrait, painted c. 1580 (at the time of the flirtation with the Duke d’Alençon) (Plate 3)). The portrait is named for the sieve held in Elizabeth’s left hand, a symbol of chastity (after the story that the Vestal Tuccia had proved her virginity by carrying water in a sieve without leakage). Behind and to the right of the queen are a group of men in courtiers’ clothes and carrying halberds, in a long colonnade, the world of men in which Elizabeth rules. Tuccia appears in Petrarch’s Triumph of Chastity (148–51) shortly before the chaste Dido, and the message of the painting seems to be that Elizabeth’s success as ruler and empire-builder will depend on her not following the path of the Virgilian Dido. But Dido as she was before she met Aeneas could be a suitable model: William Camden writes in his Annals of the reign of Elizabeth that after the defeat of the Spanish Armada coins were struck showing the Spanish fleet devastated by incendiary ships, with the legend Dux Foemina Facti, ‘A woman was conductor of the fact’, the words with which the disguised Venus described Dido.20

The figure of Dido, the Virgilian queen who at first succeeds in a masculine role before being brought low when she succumbs to love, through an all too ‘feminine’ weakness, was useful to the male writers of Elizabethan England in conceptualizing the power and potential frailty of their own queen, who famously said ‘I have but the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king.’ Issues of gender, and of appropriate gender roles, have always been central to the reception of Dido, and women writers have also used Dido to explore their place in male-dominated societies. Christine de Pizan (1365–1430), often regarded as a proto-feminist writer, finds in Dido an image of her own authorial self.21 From Boccaccio’s On Famous Women, which she translated as Des cleres femmes, Christine took the figure of the chaste Dido as the prudent and judicious city-builder celebrated in Book 1 of La Cité des dames, the symbolic city of women which Christine constructs with conscious reference to Augustine’s City of God. In Book 2 the Virgilian Dido is praised for the strength and fidelity of her love for Aeneas, virtues not shared by the unfaithful Aeneas. In the Livre de la mutacion de la fortune Christine represents herself as being transformed after the death of her husband into an ‘homme naturel parfaict’, taking on a masculine role like the widowed Dido leading her people into exile and a new city.

An identification with Dido also forms an important part of the self-presentation by the well-educated sixteenth-century French writer Hélisenne de Crenne, the nom de plume of Marguerite Briet.22 Hélisenne is the name of the female protagonist in her novel Les Angoysses douloureuses qui precedent d ‘amours, which alludes repeatedly to the story of Dido and Aeneas, as the novel explores issues of love and infidelity, and of what is expected of the female sex. These interests may also have been a strong motivation for Briet’s translation into French prose of the first four books of the Aeneid (Eneydes, 1541). Dido’s other name ‘Elissa’ resonates within Briet’s pseudonym ‘Hélisenne’.

Charlotte von Stein was the close friend and muse of Goethe in Weimar until his sudden departure in 1786 on his Italian journey, after which their relationship never fully recovered. In 1794 she wrote a tragedy, Dido, based on the version of the chaste Dido, in which Dido takes her life to remain true to her dead husband Acerbas and to avoid marriage with the African king Jarbes (Iarbas).23 Dido is betrayed by her own envoys to Jarbes, who support his suit for her hand, a historian Aratus, a philosopher Dodon, and a poet Ogon. Ogon has often been seen as a mask for Goethe, and the play a bitter comment on what Charlotte von Stein saw as her betrayal by him. Alternatively, it has been suggested that through using the non-Virgilian version of Dido she constructed an image of how she would like to be perceived, as an independent and superior human being, in reaction to an uncomfortable series of parallels between the history of her previous relationship with Goethe and the Dido and Aeneas story in the Aeneid. For example, Charlotte shared with Dido a significant cave: Goethe had a great sentimental attachment to a cave under the Herrmannstein, to which he had brought Charlotte and in which he carved their two names.24 Schiller’s 1792 translations of Books 2 and 4 of the Aeneid may have served to remind Charlotte of the parallels.

Mexico’s leading twentieth-century female poet, and a feminist icon, Rosario Castellanos (1925–74), wrote a striking Lamentación de Dido.25 She ends: ‘It would be preferable to die. But I know that for me there is no death. Because grief – and what else am I but grief – has made me eternal.’ This is the eternity of her own reception, and earlier in the poem she expresses her awareness of the long tradition of her sufferings: ‘My name carved itself in the bark of the huge tree of traditions, and every year, when the tree comes into leaf, it is my spirit, not the wind without history, it is my spirit which shakes its foliage and makes it sing.’ Dido has metamorphosed into the animating force of Fama as tradition.

Weddings and dynasties

At its simplest the story of Dido and Aeneas is one of a conflict between love and duty, or love and destiny. The Aeneid is an epic about founding cities and founding a family: Rome and the Julian gens, the family of Julius Caesar and his adoptive son Augustus, are the distant goals of the poem. Both Dido and Aeneas have lost a city and a spouse, and so might seem to be the perfect match. Dido has already founded a new city, and at first Aeneas eagerly joins in the building work. Book 4 also contains the only description of a wedding in the poem, in the shape of the weird elemental manifestations that accompany the coupling of Dido and Aeneas in the cave. There is a hint of the possibility of a new Trojan-Carthaginian blood-line in Dido’s forlorn wish, when she realizes that Aeneas is set on leaving Carthage, that at least she might be bearing his child, a ‘little Aeneas’ (paruulus Aeneas, 4.328–9). A Roman reader might have thought of a child of Aeneas’ descendant Julius Caesar, Caesarion, ‘little Caesar’ (a Greek diminutive form of the name), the offspring of Caesar and another African queen, Cleopatra, raising the nightmare for all right-thinking Romans of a Roman-Egyptian line of rulers. Caesarion was put to death by Octavian.

Aeneas’ destiny and duty is to found a city in Italy and to marry an Italian princess. That princess is Lavinia. From one point of view the most important woman in the poem, Lavinia is yet almost entirely faceless, and certainly speechless. To be accurate, her face in fact is her most vocal feature, since her only ‘action’ in the poem, her only reported ‘communication’, is her famous blush (12.64–9), whose meaning is not easy to read. Lavinia’s silence has been a provocation to the industry of supplementing the Aeneid, in Ursula Le Guin’s novel Lavinia (2008), which tells the story of the Trojans’ arrival in Italy through the mouth of Lavinia, continuing beyond the end of the Aeneid to the death of Aeneas. The Aeneid’s reticence on the character and thoughts of Aeneas’ future wife allow a space in which Le Guin’s Lavinia, engaging in a ‘nowhen’ dialogue with the ghost of her creator Virgil, is able to develop her own female perspective on the coming of the Trojans to a pastoral and georgic early Italy.26

Apart from Lavinia the other major (mortal) female characters in the Aeneid all have stories that are concluded, usually with death: Creusa (Aeneas’ first wife), Andromache (who exists in a kind of living death), Dido, Amata (the mother of Lavinia), Camilla (the Italian Amazon). Lavinia by contrast might be described as virginal potency. Her wedding to Aeneas lies beyond the ending of the poem, and within the time-span of the main narrative she and Aeneas never meet. She is not even a Helen, the fame of whose beauty made men who had never seen her fall in love with her, for all that Turnus claims that Aeneas, in taking a woman whom Turnus regards as his by right, is repeating the crime of Paris in the rape of Helen. Virgil’s management of the hero’s relationship with the woman over whom is fought the war that takes up the second half of the Aeneid is in striking contrast to the lengthy exploration of the relationship between Odysseus and Penelope as they are reunited at the end of the Odyssey. The comparison between a bride-to-be and a wife of some decades is not as off-colour as might at first appear, since Lavinia is in a sense already Aeneas’ wife, in the book of Fate, and to win her hand Aeneas has to fight a suitor in a kind of civil war that repeats on the large scale Odysseus’ battle with the suitors in his own house.

Virgil’s reluctance to narrate a fulfilled relationship between a man and a woman and the absence from the Aeneid of scenes of happy married life are reflected in Milton’s imitative practice in Paradise Lost. Milton’s epic centres largely on the vicissitudes of the relationship between Adam and Eve; Paradise Lost is, to an unusual extent, an epic about the domestic matter of marriage. Adam and Eve’s happier marital moments are narrated with allusion to married couples in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a poem of epic length and epic pretensions in which love and marriage play a prominent role.27 Adam and Eve as happy gardeners in Eden are like Vertumnus and Pomona, who seal their mutual love in the garden of Pomona in Metamorphoses 14. Their hospitality to their angelic visitor Raphael makes them a younger version of Philemon and Baucis who offer humble hospitality towards the gods who come visiting in Metamorphoses 8. In the shared repentance that restores marital harmony after Adam and Eve have quarrelled after the Fall they are compared in a simile to the devoted couple Deucalion and Pyrrha, who restore the human race after the Flood in Metamorphoses 1 (Paradise Lost 11.8–14). In contrast, Milton highlights key moments in the history of the Fall by allusion to the Virgilian tragedy of Dido and Aeneas. When Adam looks longingly after Eve for the last time before the Fall, the last moment of innocent conjugal desire, there is an echo of Aeneas’ last view of Dido in the Underworld: with Paradise Lost 9.397–8 ‘Her long with ardent look his eye pursued | Delighted, but desiring more her stay’ compare Aen. 6.475–6 ‘Aeneas was no less stricken by her unjust fate (casu percussus iniquo), and long did he gaze after her (prosequitur […] longe), weeping and pitying her as she went.’ An awareness of the Miltonic lines retrospectively lends fresh point to casu […] iniquo: Eve is about to meet an ‘adverse fall’. The most emphatic allusion to the Dido and Aeneas story comes at the eating of the apple, first by Eve, and then by Adam, now united with Eve in original sin as he knowingly partakes of the apple: Paradise Lost 9.781–4 ‘she plucked, she ate: | Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat | Sighing through all her works gave signs of woe, | That all was lost’; 1000–4 ‘Earth trembled from her entrails, as again | In pangs, and Nature gave a second groan; | Sky loured, and muttering thunder, some sad drops | Wept at completing of the mortal sin | Original.’ Later in human history there will be similar signs in the elemental accompaniments to the ‘wedding’ of Dido and Aeneas in the cave, the moment of Dido’s ‘fall’, Aen. 4.166–70: ‘Earth and Juno, giving away the bride, first gave a signal: lightning flashed and sky witnessed the wedding, and the Nymphs cried out on the mountain top. That day first brought death, that day first brought woe.’28

One response to the Virgilian unwillingness to develop a narrative of wooing and wedding was to supplement the Aeneid. This is the strategy of the Roman d’Eneas, written probably around 1160 at the court of the Plantagenet king Henry II, and one of the earliest of the French romances.29 Eneas’ affair with Dido is elaborated at even greater length than in the Aeneid. This disastrous relationship, in which female desire and intelligence threaten the hero’s mission, is balanced in the last part of the poem with the narrative, spread out over two thousand verses, of the love affair of Lavine and Eneas, ending with the wedding of the happy couple. But not before much erotic pain, first on the part of Lavine, whose experience and inner debates are described at great length, and then of Eneas, who falls in love with Lavine after reading a letter that she has delivered to him wrapped round an arrow. Love strikes through their gazes on each other, Lavine looking down to the battlefield from her tower, and Eneas looking up to the tower. Eneas confesses to himself (9090–4) that ‘I have never known such torment; if I had had such feelings towards the queen of Carthage, who loved me so much that she killed herself, my heart would never have left her.’ Through this mutual love Eneas becomes the ideal chivalric lover. Love gives Eneas strength in his fight with Turnus; Lavine says that ‘if he has any care for my love, when he sees me at the window, he will become much the bolder’ (9392–4). Lavine’s sorrows in her love for Eneas, elaborated through copious use of Ovid’s amatory works, provided a model of romantic love for the medieval tradition of courtly narrative. In this second major episode of erotic obsession in the Roman d’Eneas love helps rather than hinders (as it had in the case of Dido) the pursuit of a heroic goal, and a woman’s desires and ruses end up by furthering the goals of patriarchal power and lineage. A circumstantial account of the wedding of Aeneas and Lavinia is also contained in the Book 13 of the Aeneid composed in Latin in the early fifteenth century by Maffeo Vegio, in order to tie up the ends left loose at the end of Virgil’s Book 12 (on Vegio see p. 85).30

Dynastic epic

The detailed attention paid by the Roman d’Eneas to the relationship between Aeneas and his future queen, leading to a marriage through which he will succeed to a kingdom, may reflect the historical reality of the powerful queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, through whom the English king Henry II, Eleanor’s second husband, succeeded to his French dominions.31 The historical context may have given a strong impulse to the positive association of the power of love and political power that becomes the norm in the Italian epic romance of the sixteenth century and in Renaissance epics in other languages. Where Virgil’s warrior-maiden Camilla is deflowered in death, Amazonian warriors of the Renaissance combine military prowess with erotic love and are destined to found dynasties. Ariosto’s Bradamante will marry the Saracen warrior Ruggiero, once he has converted to Christianity, and the couple will become the ancestors of the d’Este family of Ferrara. Spenser’s Britomart pursues her beloved Artegall, by whom she will eventually become the ancestor of the Tudor kings and queens. In Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata the dynastic ancestress is the representative not of the Virgilian Amazon, but of the Homeric-Virgilian figure of the seductress and temptress, Circe-Calypso-Dido. The Saracen sorceress Armida leads the hero Rinaldo away from his heroic duties as the Christian champion in the siege of Jerusalem to her enchanted garden. From there he is recalled to the world of epic by Carlo and Ubaldo, playing the role of Mercury in Virgil’s Carthage. Rather than commit suicide, Armida follows Rinaldo, and is finally converted from her mission of revenge into the Christian wife of Rinaldo, and the two become ancestors of the d’Este family. In the dynastic romance, honour and love as motivating forces are brought into a harmonious collaboration, in a revision of the conflict between fame and love that makes the Aeneid in many ways so bleak a poem.32

We have seen above how the story of Queen Dido is used in often oblique and not altogether comfortable ways to comment on the historical Queen Elizabeth and on speculation about a possible dynastic union with the Duc d’Alençon. An unembarrassed rehabilitation of the Dido story in the service of a celebration of the beginning of the Tudor dynasty is found in Pancharis by Hugh Holland, later author of a dedicatory poem in the First Folio of Shakespeare. Only the first book was completed, published in the year (1603) of the death of the last monarch of the dynasty, Elizabeth. It is an account of ‘the preparation of the love between Owen Tudor and the Queen’ (Catherine of Valois, the widow of Henry V), in which the plot of Dido and Aeneas is turned to the celebration of a wound of love that leads to the line of the Tudors. Catherine, like Dido, is initially determined to preserve honour and reputation by remaining faithful to her dead husband, but Venus’ and Cupid’s plot to make Owen fall in love with her will eventually win out, this time without tragic consequences. Spenserian in language, the poem self-consciously swerves from the martial subject matter of traditional epic, so reversing Spenser’s exchange of his pastoral oaten reed for ‘trumpets stern’ (The Faerie Queene I prol. i.): Pancharis 36 ‘That argument a louder trump doth ask, | To sound a march too slender is my reed; | Enough is it to tune a courtly masque.’ The Ovidian is mingled with the Virgilian, and in the dedication to Queen Elizabeth a famous Ovidian tag is readjusted in line with this epic masque’s harmonization of love with the proper exercise of royal power: ‘And thou, O second sea-borne Queen of Love! | In whose fair forehead love and majesty | Still kiss each other’ – in contrast to Jupiter’s descent from his royal dignity to indulge his passion for Europa: ‘Between the state of majesty and love is set such odds, | As that they can not dwell in one’ (Golding, Metamorphoses, 2. 1057–8; Ovid, Met. 2.846–7 non bene conueniunt nec in una sede morantur | maiestas et amor).

Non-epic Didos

Virgil’s Dido narrative is marked by a generic instability. Epic is diverted into the world of tragedy, and as a consequence the majestic Dido descends from her epic throne into an erotic obsession reminiscent of the self-absorption typical of Latin love elegy. Generically, the reception of the Dido story has also been very varied, in epic, tragedy, elegy, lyric, the novel and not least opera.

The reception of Dido was given a decisive twist by Ovid, one of Virgil’s earliest and most acute readers. In his self-defence to Augustus from exile, the elegiac poet of love claims that love is a central concern of epic too: ‘What is the Iliad itself, if not a disgraceful adulteress over whom there was a fight between her lover and her husband? […] Or what is the Odyssey, if not one woman wooed by many suitors because of love, while her husband was away?’ (Tristia 2.371–2, 375–6). The Aeneid too, Ovid tells Augustus, is read largely for its erotic content: ‘And yet that happy author of your Aeneid brought his “Arms and the man” into a Carthaginian bed; no part of the whole work is more often read than the love joined in an illegitimate union’ (Tristia 2.533–6). Dido is naturalized in the solipsistic world of elegiac erotic complaint in the seventh of Ovid’s Heroides, love letters of abandoned mythological heroines. Dido pens her epistle to Aeneas as he is on the point of leaving Carthage, but no reply is forthcoming or indeed expected. There is thus no answer to Dido’s portrayal of Aeneas as a liar and deceiver, and to her charge that the pious hero is in truth a monster of impiety. Virgil’s Dido had wished that if only she were pregnant by Aeneas, she would have ‘a little Aeneas’ by which to remember him; Ovid’s Dido thinks that she may really be pregnant, in which case by forcing her to commit suicide Aeneas will be guilty of a double murder (Her. 7.133–8).

Heroides 7 is not just a free composition on the theme of Aeneid 4, but a particular way of reading Virgil’s Dido, one that privileges the values of love and personal relationships over the calls of fate and empire, a woman’s point of view. Ovid calls attention to the prior existence within Aeneid 4 of elements of love elegy, a genre bursting on to the Roman literary scene at the same time as Virgil was writing the Aeneid. Dido’s point of view has also been that of many modern readers, attracted to the ‘private voice’ of the Aeneid, as opposed to the ‘public voice’, in a prevalent ‘two voices’ approach to the poem that was reinforced by feminist readings (see Chapter 1 p. 16).

An alternative reading strategy has been to contrast Virgilian and Ovidian views of the world: Virgil writes the story of the painful but necessary struggle of the hero to achieve his destiny, forced to sacrifice much along the way, while Ovid gives voice to those victimized by the forces of history. The tension between these two ways of reading is vividly presented in Chaucer’s House of Fame.33 In the first book the narrator ‘Geffrey’ views scenes from the Aeneid engraved in a temple of Venus. The greatest space is devoted to the Dido episode. The narrator takes the view that Aeneas only ‘seemed good’, but in reality was false, ‘for he to her a traitor was’ (267). Dido is given a lengthy complaint, which focuses on the damage done to her fame, and reputation by what people say and will say about her. ‘For through you is my name lorn, | And all mine acts red [spoken] and sung | Over all this land, on every tongue. | O wicked Fame’ (346–9). She expects to be harshly judged: ‘Lo, right as she hath done, now she | Will do eft-soons, hardly [certainly].’ The reader who wants to know ‘all the manner how she died, | And all the words that she said’, is told to ‘read Virgil in Eneydos | Or the Epistle of Ovid’ (378–9). Reference to Heroides 7 triggers a catalogue of men who were false lovers, in fact a catalogue of seven other of Ovid’s Heroides. Chaucer returns from this Ovidian digression to the straight path of the Aeneid at the end of the section on Dido and Aeneas: ‘But to excuse Aeneas | Fully of all his great trespass, | The book sayeth Mercury, sauns fail, | Bade him go into Itayle, | And leave Afric’s region, | And Dido and her fair town’ (427–32). Finally, then, a clear line is drawn between the Virgilian narrative of the hero of destiny and Ovidian female complaints. Dido’s earlier reference to ‘wicked Fame’ reveals Chaucer’s awareness that the Fama of Aeneid 4 looks beyond Virgil’s legendary narrative to the competing judgements on Dido in the literary tradition.

In Aeneid 4 Dido is given six long speeches, two addressing Aeneas, two giving instructions to her sister Anna, and two monologues, the second of which climaxes in her dying curse against Aeneas and his descendants. Aeneas is given only one lengthy section of direct speech, a vain attempt to justify to Dido his departure from Carthage. He pleads the command of the gods and the Italian kingdom owed to his son Ascanius, but succeeds only in provoking her to greater anger and scorn. Aeneas is otherwise notable for his taciturnity in Aeneid 4. Virgil’s disproportionate focus on the thoughts and feelings of Dido has a long afterlife in smaller-scale complaints, laments and psychological portraits of Dido, beginning with Ovid’s unanswered epistle to Aeneas. Laments of Dido proliferate in the Middle Ages. Helen Waddell writes of the wandering scholar poets: ‘Dido they took to their hearts, wrote lament after lament for her, cried over her as the young men of the eighteenth century cried over Manon Lescaut.’34 In Gottfried of Strassburg’s Tristan, Tristan, disguised as a minstrel, plays the ‘lay of Dido’ for Isot and Gandin. The Carmina Burana include a lament by Dido beginning o decus, o Libie regnum, Kartaginis urbem ‘O my glory, O kingdom of Africa, city of Carthage’.35 The fragmentary collection La Terra Promessa (1935–53) by the Italian Hermeticist poet Giuseppe Ungaretti draws out themes of loss and desire in the Aeneid (the title refers to Italy as Aeneas’ ‘promised land’); it includes 19 brief ‘Choruses descriptive of Dido’s states of mind’ (‘Cori descrittivi di stati d’animo di Didone’), in which Dido’s despair is generalized into an autumnal grief for (in Ungaretti’s words) ‘the disappearance of the last gleams of youth from a person or from a civilization, for civilizations are also born, grow, decline and die’.36 The link in the Aeneid between the death of Dido and the future decline and destruction of her city, seen in the bright summertime of its first building (Aen. 1.430), is taken up by others. English readers of this book will perhaps remember Dido particularly for her haunting lament ‘When I am laid in earth’ at the end of Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas.

Dido’s, however, is only one point of view. The events of Aeneid 4 are presented as conflicts of desires and duties, conflicts both between Aeneas and Dido, and within each of the two characters. These conflicts call for judgements and decisions on the part of the actors, and also from readers, provoking a critical debate about the culpability for the tragic outcome of the encounter between Trojans and Carthaginians that has lasted from antiquity down to the present day. It is a debate whose intensity is matched only by the disagreement as to how to judge the final action in the poem, Aeneas’ killing of Turnus. The word ‘tragic’ is used with precision: the reader is alerted to the close affinity of the story of Dido’s downfall with the genre of tragedy through formal signals, such as the use of the word scaena, literally ‘stage’ of a theatre, to refer to the backdrop of woods in the harbour at Carthage (Aen. 1.164), and by the delivery to Aeneas by his mother, playing the part of a virgin huntress and wearing ‘buskins’ (1.337), of a kind of Euripidean tragic prologue summarizing Dido’s previous history. Culpa, the word used of Dido’s ‘fault’ in surrendering to her love for Aeneas (4.172), could be a translation of Greek hamartia, the Aristotelian tragic ‘flaw’. Some scholars have even tried to find in the structure of Aeneid 4 the schema of a five-act drama.

The agonistic genre of Attic tragedy stages debate and the clash of competing values and responsibilities. By building a tragic dialectic into his epic narrative, Virgil seems once again to have pre-programmed the reception of his Dido story, in a series of tragic and operatic dramatizations. The impress of Aeneid 4 is clearly visible in the tragedies of Seneca the Younger. In the Medea and the Phaedra Seneca chooses protagonists whose careers in previous tragedies had been part of the intertextual mix out of which Virgil had forged his Dido. Tragic aspects of Dido return, as it were, to their original owners in Seneca’s plays. Senecan elements work their way back into post-classical dramatizations of the Dido story, for example a neo-Latin Dido of 1559 by Aulus Gerardus Dalanthus, which contains much material from Seneca’s Phaedra.37

Dido figures large in the revival of the classical form of tragedy from the sixteenth century onwards, in both Latin and the vernaculars.38 Some of these plays are close adaptations, amounting at times almost to translations, of the Virgilian text, and others are free developments of the Virgilian plot. Aeneas’ inner struggle between love and duty is explored at length, and further erotic entanglements are introduced. In Italy there were plays by Alessandro Pazzi de’ Medici (1524), Giraldi Cinthio (1543) and Lodovico Dolce (1547). In the prologue of Dolce’s Didone, the best known of the Italian Dido dramas, the divinity who motivates the action is Cupid. Having inspired Dido with the poison of love, as he does on Venus’ instructions in Aeneid 1, he now goes a step further and announces his intention to make Dido kill herself and to bring about the sack of Carthage, as vengeance for Juno’s persecution of Aeneas. He will raise the shade of Sicheo (Sychaeus) and madden Dido with a serpent from the hair of the Furies. In this last detail Dolce signals a connection between Cupid’s erotic inflaming of Dido in Aeneid 1 and the Fury Allecto’s infuriation in Aeneid 7 of Amata against the marriage of her daughter Lavinia to Aeneas, a connection in the Virgilian text to which modern critics have drawn attention. In an early scene between Enea and his close companion Acate (Achates), here a figure for Aeneas’ conscience, Aeneas is torn between his desire to stay in Carthage and the god’s command to leave, between love and the pursuit of honour and fame. The messenger-speech reporting the death of Dido is close to the Virgilian narrative, but ends with a translation of the epigram that Dido writes for herself at the end of Ovid Heroides 7 (2051–4): ‘Thus did Aeneas leave to Dido the sword and the cause of her death; thus, for having loved too much, the famous lady has killed herself by her own hand.’

Etienne Jodelle founded French tragedy in the antique manner with his Cléopatre captive (1552), praised by the poets of the Pléiade. The date of his tragedy Didon se sacrifiant is unknown, but was possibly prompted by Du Bellay’s publication of his translation of Aeneid 4 in 1558.39 In the first act Enée runs through the horrors of the sack of Troy and his subsequent wanderings, the events that he narrates at length in Aeneid 2 and 3, but finds that all these are less terrible than the prospect of having to betray Dido’s love (pp. 156–8). In making a connection between the frame-narrative of Dido and Aeneas in Aeneid 1 and 4 and Aeneas’ flashback narrative in Aeneid 2 and 3 of the sack of Troy and his wanderings before reaching Carthage, Jodelle shows an interest in drawing out interconnections between different parts of the Aeneid which is anticipated in Dolce’s Didone, which Jodelle possibly knew, and foreshadows modern studies of the ways in which framed and framing narratives reflect on each other. Later, in Act III, Aeneas says that the present agitation of his spirit makes him relive his experience in the storm at the beginning of the Aeneid (pp. 192–3). A psychological reading of the fury of the storm raised by Juno is one of the many possible ways of responding to that highly symbolic episode. Dido amplifies her threat to Aeneas to pursue him with a Fury’s black torches (Aen. 4.384–6) with a translation of Juno’s words as she sets about calling up Allecto in Aeneid 7, ‘And if the gods of the sky will not do me justice, I will stir up, I will stir up (‘j’esmouvrois’) the infernal abodes’ (cf. Aen. 7.312 flectere si nequeo superos, Acheronta mouebo).

The invectives of Jodelle’s Dido contain attacks on superstition and religion; a Lucretian scepticism about the value of religion, already present at points in Aeneid 4, surfaces in the Chorus’s retort to Aeneas’ defence that obedience to the gods requires him to leave Dido that ‘Were it not for Religion, Iphigeneia would still be alive’ (p. 177), alluding to Lucretius’ use of the sacrifice of Iphigeneia as an example of the evils of religion. But in Act III Dido’s anxiety that she may have offended Venus leads her to utter a prayer to Venus as a universal goddess of love that echoes the Hymn to Venus that opens Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things (pp. 186–8). Aeneas’ deep feelings for Dido, in Jodelle’s and other Dido tragedies, include pity. Pity is the last emotion that we are told Virgil’s Aeneas feels for Dido, as he watches her shade walk away from him in silence in the Underworld (Aen. 6.476 miseratur euntem).

Jodelle’s Didon se sacrifiant is one of the models for the tragedy of the same name by the leading French playwright of the early seventeenth century, Alexandre Hardy (1624), which also plays up Aeneas’ indecision and his pity for Dido;40 Aeneas promises that he will come back and pay Dido a visit after he has arrived in Italy. Dido enjoyed a great popularity on the seventeenth-and eighteenth-century European stage, in the company of other royal heroines whose stories involved difficult choices between love and duty, Sophonisba, who killed herself after her love was renounced by the Numidian king Masinissa, and the Jewish queen Berenice, who survived the renunciation of her love by the Roman emperor Titus.

Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragedy of Dido, Queen of Carthage may be Marlowe’s earliest dramatic work, possibly written while he was still at Cambridge (1586?). It owes little or nothing to the continental tradition of Dido tragedies. Where most of those dramatize only the last part of the story in Aeneid 4, Marlowe’s play covers the events of Books 1 and 4 from the Trojans’ landing at Carthage to the death of Dido, followed immediately by the suicides of Iarbas, Dido’s thwarted suitor, and Anna, who in this version is in love with Iarbas. In this extension and complication of the Virgilian erotic triangle of Dido, Aeneas and Iarbas, The Tragedy of Dido is in the company of numerous other adaptations of the Virgilian plot. Like William Gager’s Latin Dido, performed probably a very few years before Marlowe wrote his Dido, but which Marlowe seems not to have known, the play at points tracks Virgil’s Latin very closely. Dido, Queen of Carthage has provoked very varying critical reactions, some seeing in it a celebration of erotic desire, and others a condemnation of passion.41 The debate between ‘romantic’ and ‘pro-duty’ Marlovians is parallel to, but, it would seem, largely independent of, the continuing debate among Virgilians as to the assessment of the relative claims of the ‘private’ and ‘public’ voices in Aeneid 4. The first scene takes us to Olympus, but only to discover Jupiter dandling Ganymede upon his knee: what in Virgil is mentioned briefly as one of the causes of Juno’s hostility to the Trojans (Aen. 1.28 rapti Ganymedis honores: Ganymede was a Trojan) is expanded into an Olympian version of the invitation to love in Marlowe’s lyric The Passionate Shepherd to His Love. Marlowe heightens the generic polymorphism that already characterizes the Virgilian Dido narrative, and he follows in the line of Ovidian readers of the story.42

Marlowe’s Dido is one of his least-read plays, and none of the continental Renaissance Dido plays ever achieved classic status to equal that of Racine’s Bérénice, for example. In the case of opera there are two acknowledged masterpieces, Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (libretto by Nahum Tate)43 and Berlioz’ Les Troyens, the last three of whose five acts are on the story of Dido.44 But these standard items in the repertoire are the tip of an iceberg of operas on Dido. The first of these was Cavalli’s Didone (Venice 1641; librettist Giovanni Busenello,45 who also wrote the libretto for Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea). In Busenello’s libretto Dido directs her anger against herself, not Aeneas, tormented by her own conscience. A focus on Dido’s guilt and expiation for her betrayal of her queenly responsibilities is found much later in a stream of German Dido tragedies produced between the 1820s and World War I.46 In Busenello’s second version of the libretto a repentant Dido becomes the happy wife of Iarbas, one of a number of rewritings of the story with a happy ending, catering for the Baroque predilection for musical dramas with a lieto fine. Between 1641 and 1863, the date of the first performance of Berlioz’ Les Troyens, about a hundred Dido-operas have been counted.47 About 70 of these are settings of Pietro Metastasio’s libretto Didone abbandonata, Metastasio’s first great hit when it was performed during Carnival in Venice in 1724, set to music by Domenico Sarro.48 Metastasio complicates the plot with erotic and political intrigue, disguise and doubletalk: Dido’s sister, here called Selene, is also in love with Aeneas, perhaps following a variant tradition already current in antiquity that Anna, not Dido, was in love with Aeneas. Selene is repeatedly in danger of giving away her feelings to Aeneas, but covers her own emotions by telling him that she shares Dido’s sufferings because (I.ix.) ‘She lives in me, and I live in her, in such a way that all her woes are my woes’. This is a clever twist on the very close relationship that binds the Virgilian Dido to Anna, introduced as her ‘like-minded sister’, or even ‘soul-partner’ (Aen. 4.8 unanima). Jarba’s confidant Araspe is in love with Selene, and Dido has a wicked adviser Osmida, who tries to betray her to Jarba. Aeneas is much given to ‘pietà’ in the sense of ‘pity’. At the end of the opera Jarba has launched a full-scale attack on Carthage and the city is in flames. Dido hurls herself into the burning palace. In the version of the opera performed at the Spanish court in 1754, in a curious prefiguration of the ending of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, the sea rises and dense clouds gather, to the accompaniment of stormy music. The furious clash of fire and water is finally won by water, whereupon the sky clears and the music turns joyful, and from the waves rises the bright palace of Neptune the calmer of storms. In the ‘Licenza’ (Envoy) Neptune looks into the future when as the god of calm seas he will carry the laws of Spain to remote worlds, developing the political imagery of Neptune’s calming of the storm in Aeneid 1. The allusion here is to the peace-loving policies of Ferdinand IV of Spain after the Treaty of Aix La Chapelle (1748), ending the War of the Austrian Succession.49