FROM SAN JUAN HILL

TO CAPITOL HILL

Among the many visitors to Camp Wickoff for the joyous homecoming of the conquering hero was a man who quietly waited his turn behind hordes of family and friends, newspapermen and cartoonists, common well-wishers and even the president of the United States. This man bore the memorable name Lemuel Ely Quigg, and he represented Republican Senator Thomas Collier Platt of New York, ostensibly to say “welcome home.” Quigg was known as Boss Platt's fixer, a reliable political operative. Platt himself, almost two decades earlier, had been a similar lackey to Senator Roscoe Conkling, the scourge of TR's father in the Collector of the Port of New York episode. Conkling and Platt had both been opponents of young TR in his Assembly days and at the 1884 convention.

Platt was known in those early days, derisively, as “Me Too Platt,” so dubbed by cartoonists after his protector Conkling had maneuvered a U.S. Senate seat for him. In 1881, President Garfield had asserted his independence from the Stalwarts, as Rutherford Hayes had attempted to do during his presidency, and ironically over the same patronage issue: the appointment of a Customs Collector for the Port of New York. Conkling, in an attempt to establish his party influence over President Garfield, resigned his Senate seat over the issue, thinking he would be returned triumphantly to his position. (At the time, U.S. senators were elected by state legislatures, not by popular vote.) Platt, the compliant junior senator, followed suit. It was a bold political gambit by Conkling, but the legislature decided it had had enough. In a surprise move, it elected two replacements to the U.S. Senate.

Conkling was, of course, disgraced. His public career was over. Still, he continued to exercise residual power behind the scenes, and he gained a quick fortune as a trial lawyer. When his old henchman “Chet” Arthur became president, he nominated Conkling to a Supreme Court vacancy, but Conkling declined. This awkward situation helped seal Arthur's fate both as a politician, and as president.

Meanwhile, Thomas C. Platt patiently rebuilt his career from the ground up. He eventually became a Republican boss of New York State more powerful, and certainly more savvy, than his former chief. By 1898 he had been appointed senator for the second time. Now, as Boss and senator of the Empire State, Platt approached Theodore Roosevelt in the person of his liaison, Lemuel Ely Quigg.

Elections were a few months away. The Republicans had an incumbent governor, Frank Black, a man in the pocket of Platt, a mesmerizing speaker, but suffering widespread opprobrium for presiding over a scandal-ridden administration. New York Central Railroad president Chauncey Depew, the GOP candidate for the U.S. Senate, told Platt in frustration that the best defense of the governor he could mount, when asked on the campaign circuit, was that “only” a million dollars of the infamous Canal Frauds could be pinned on Black. If the Republicans were to retain control of state government—no certain thing—they needed to jettison Black and find a popular replacement. Theodore Roosevelt, born in Manhattan, scion of New York aristocracy, former state Assemblyman and candidate for New York City mayor, had a sterling résumé. Of TR's bona fides, however, the most important to Platt was his popularity. (In politics, this translates to “Electability.”) So Platt sent Quigg to TR in his tent at Montauk, offering the party's nomination.

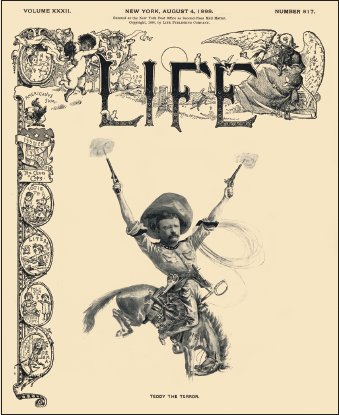

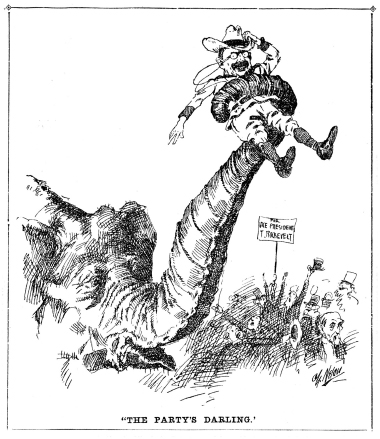

Even before Roosevelt was elected governor, speculation was rife of his presidential possibilities. (McKinley was often depicted by cartoonists as Napoleon because of his facial resemblance.)

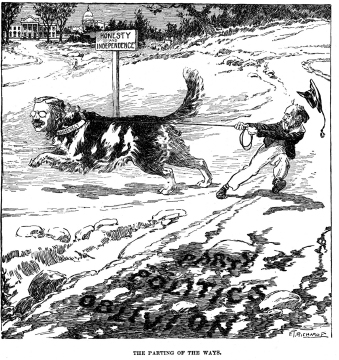

Roosevelt was “dee-lighted” (his trademark pronunciation), but there were flies in the ointment. First, Independent reformers, many of TR's longtime allies in assorted municipal battles, were in one of their quadrennial danders, determined in 1898 to spurn both Democrats and Republicans and elect one of their own to the governor's chair. The feelers came from the editorial columns of The New York Evening Post and The Nation magazine, and various clergymen and reformers. They anointed Theodore Roosevelt, though they never fully secured his assent. TR was not comfortable spinning off from his main party to run on an Independent ticket. He knew well enough that a division of Republican (or anti-Democrat) ranks would assure a Democrat victory. This was a time in the pendulum-swings of New York politics when the worst Tammany Hall elements controlled the state Democrat party. Roosevelt declined the Independents' overture with thanks and offered assurances that he was “one of them” as always; that his administration would be as honest and reform-oriented as they could wish. Their response was common to “purists” in politics, in contrast to “practical reformers,” as TR termed himself: they rejected him vehemently. Political hell hath no fury like a “Goo Goo” (good-government zealot) scorned.

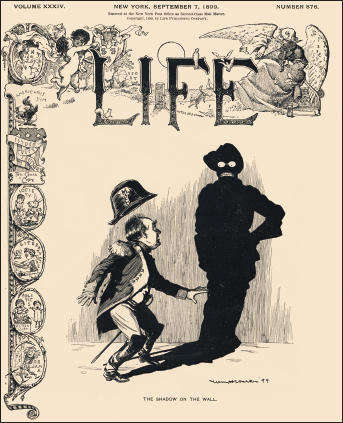

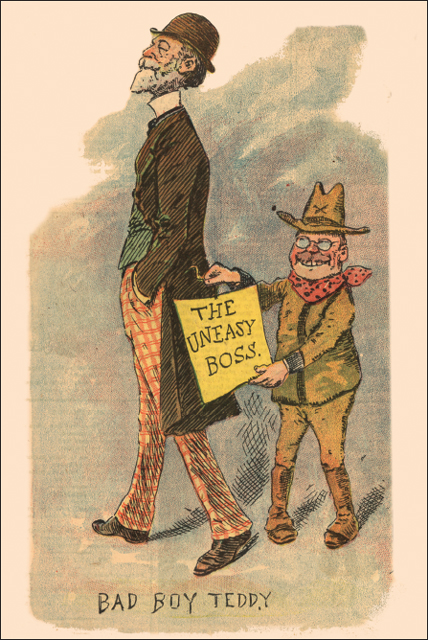

F. T. Richards of Life recognized that Platt must have wondered just who was the “Boss” after all. Note that he drew the White House at the end of the path TR was choosing.

Roosevelt's relationship with Boss Platt, a particular worry of the Goo Goos, was the other fly in the ointment. In the political dance that opened with Quigg's visit, TR made it clear that he would demand independence; Platt required obeisance. Ultimately, Roosevelt accepted the nomination of the regular party and promised to consult Platt on all matters of state business and appointments. As it turned out, after he was elected, TR even stroked Platt further by having weekly breakfasts in the famous “Amen Corner” of the senator's Manhattan hotel, for all the public to see. The drawback for Platt in all those consultations and breakfasts was a particularly Rooseveltian combination of consistency, integrity, and obstinacy. In his autobiography, Platt recalled that TR “religiously fulfilled this pledge [to consult]…although he frequently did just what he pleased.”

Before any of this, of course, there was the election. A brief scare about TR's eligibility (he had paid taxes in the District of Columbia during his work in the Navy Department) was resolved by Republican super-lawyer Elihu Root, one of the original backers of young Roosevelt's first political campaign. Then there was the matter of uniting factions loyal to the tainted Governor Black and the spurned suitors from the Good Government societies. Roosevelt left those details to the “Easy Boss” Platt. Meanwhile, he embarked on an astonishing whirlwind campaign around the state talking directly to the people. On trains and by coach, TR traveled everywhere and was seen by everyone, or so it seemed—and if not, it wasn't due to lack of effort by brass bands and the ubiquitous Rough Riders, many of whom stepped in to help. It was indeed a hot time in the old town.

The Democrats were united behind Judge Augustus van Wyck. The two Dutchmen fought it out—TR's popularity against van Wyck's strong argument that beneath the popular Roosevelt were the rotted floorboards of a corrupt party. In the November election, more than 1.3 million votes were cast; Theodore Roosevelt, just turned forty, was elected governor by a margin of 17,786. It had been quite a year for TR. He had gone from being a minor government official in the McKinley administration, to a genuine war hero, to the governor of the most powerful state in the Union.

The Roosevelt family moved to Albany, a provincial city in the eyes of Manhattanites, and not much changed from when young TR lived in rooming houses there during his years in the Assembly. Now his home would be the Executive Mansion, and he had a large family to fill it. Alice, almost fifteen, already portrayed the free spirit that would characterize her very public persona for decades to come. She disliked the lack of excitement and glamour in Albany. At times she paid long visits to her maternal grandparents in Chestnut Hill, or to her beloved “Auntie Bye” or “Bamie,” TR's sister Anna. Theodore and Edith hoped that Bye might be a palliative to Alice's obstreperous tendencies.

She wasn't. But the rest of the children—Theodore (born in 1887), Kermit (1889), Ethel (1891), Archibald (1894), and Quentin (1897)—were happy: they had a governor's mansion through which to romp.

The governor, meanwhile, found his own places to romp. He “romped” through precedents, political propriety, the “old way of doing things,” and, especially, the prerogatives of Boss Platt. He endorsed Platt's slate of nominees when he approved of them, but he frequently, in some very public clashes, appointed his own people. The newspapermen and cartoonists, as always, were eager to report on TR's activities, and their news reports and cartoons helped him proceed with confidence. He had already learned the tactic of going over the heads of the political establishment, straight to the people. The ebullient character depicted by cartoonists—flashing teeth, bright spectacles, constant motion, and the frequent exclamation of the approving phrase “Bully!”—had become a figure of both familiarity and curiosity to the public.

Probably the most spectacular contretemps with Platt came when the governor supported legislation placing a tax on the franchises of public utilities. Roosevelt believed this to be a proper source of revenue, as operators were granted, in effect, monopoly status, and were profiting from common, public domains, paying no taxes in return. Sometimes, when no monopolies but only subsidies were at play, these entities stifled honest competitors. Growing out of a dispute involving street-car fares in Buffalo, a bill to tax public franchises—“common sense” in the governor's words—was twice defeated in the legislature; Roosevelt supported it more fervently, however, instead of retreating from it. In New York, the governor was entitled to submit bills on his own, and out of order on the legislative calendar. TR took full advantage of this to push his bill. This action signaled his clear priority. Besides his believing it to be good common sense, TR also gave the bill his support because he realized that the system of public works and economic efficiency—theoretically, capitalism at its best—had calcified into a network of schemes. Monopolies were protected and were gouging the public with arbitrary rate hikes; interlocking groups of cronies sat on boards and court benches and legislative seats, and favors were exchanged for campaign donations—or bald-faced bribes. Some businessmen even intimated that the taxes would double what they were already paying to politicians and judges for protection from this sort of thing. But with reform of a corrupt system as the wind in his sails, Roosevelt prevailed.

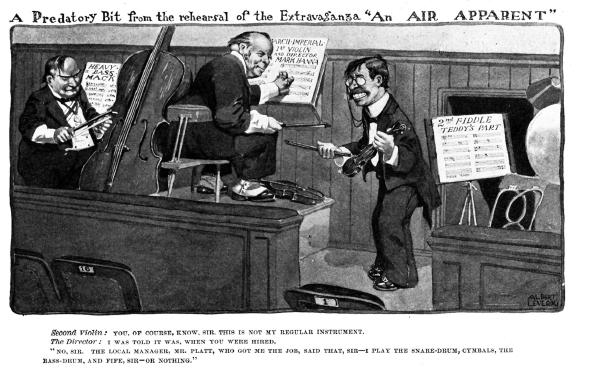

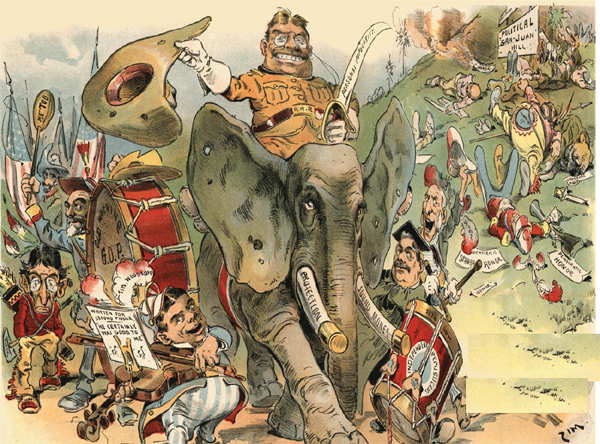

As cartoonists predicted and Boss Mark Hanna (center) had feared, “What to do with Roosevelt?” was the question of the day after the new administration took office in March of 1901. Perhaps the question would be resolved in the fall, because Congress took off for all spring and summer, leaving politics too on a bit of a vacation…. A cartoon by Albert Levering in Life, 1901.

Senator Platt was fairly beside himself, wondering whether he had created a Frankenstein's monster in securing the governorship for Roosevelt. The breakfasts with the governor were producing little more than heartburn. He wrote TR a letter, a severe scolding sandwiched between the diplomatic niceties:

When the subject of your nomination was under consideration, there was one matter that gave me real anxiety. I think you will have no trouble in appreciating the fact that it was not the matter of your independence. I think we have got far enough along in our political acquaintance for you to see that my support in a convention does not imply subsequent “demands,” nor any other relation that may not reasonably exist for the welfare of the party…. The thing that did bother me was this: I had heard from a good many sources that you were a little loose on the relations of capital and labor, on trusts and combinations, and, indeed, on those numerous questions which have recently arisen in politics affecting the security of earnings and the right of a man to run his own business in his own way, with due respect of course to the Ten Commandments and the Penal Code. Or, to get at it even more clearly, I understood from a number of business men, and among them many of your own personal friends, that you entertained various altruistic ideas, all very well in their way, but which before they could safely be put into law needed very profound consideration…. [T]o my very great surprise, you did a thing which has caused the business community of New York to wonder how far the notions of Populism, as laid down in Kansas and Nebraska, have taken hold upon the Republican party of the State of New York.

Similar criticisms would be leveled at Theodore Roosevelt time and time again in the years to come. But his response was as old as his first public statements, and consistent with his lifelong view that the best way to preserve capitalism, and the Republic itself, was to reform them when necessary. As he said in many ways and places, he could no more tolerate wrong committed in the name of property than wrong committed against property. Platt did not yield, however, claiming that the governor was flirting with socialism and communism for supporting a tax on public franchises like street lines and water companies.

TR's reply to Platt included a firm rejection of the senator's lecture:

I knew that you had just the feelings that you describe; that is, apart from my “impulsiveness,” you felt that there was a justifiable anxiety among men of means, and especially men representing large corporate interests, lest I might feel too strongly on what you term the “altruistic” side in matters of labor and capital and as regards the relations of the State to great corporations…. I know that when parties divide on such issues…the tendency is to force everybody into one of two camps, and to throw out entirely men like myself, who are as strongly opposed to Populism in every stage as the greatest representative of corporate wealth, but who also feel strongly that many of these representatives of enormous corporate wealth have themselves been responsible for a portion of the conditions against which Bryanism is in ignorant revolt.

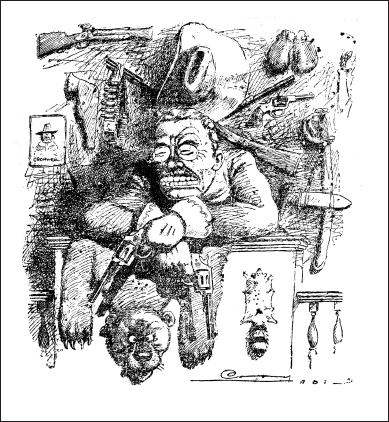

Charles Nelan in The New York Herald.

I do not believe that it is wise or safe for us as a party to take refuge in mere negation and to say that there are no evils to be corrected. It seems to me that our attitude should be one of correcting the evils and thereby showing that, whereas the Populists, Socialists, and others really do not correct the evils at all, or else only do so at the expense of producing others in aggravated form, on the contrary we Republicans hold the just balance and set ourselves as resolutely against improper corporate influence on the one hand as against demagogy and mob rule on the other.

[Party leaders] urged upon me that I personally could not afford to take this action, for under no circumstances could I ever again be nominated for any public office, as no corporation would subscribe to a campaign fund if I was on the ticket, and that they would subscribe most heavily to beat me…. Under all these circumstances, it seemed to me there was no alternative but to do what I could to secure the passage of the bill.

As the time for Roosevelt's renomination approached, Platt found himself confronted with the irony of his 1898 dilemma with Governor Black, this time turned on its head: he had a Republican incumbent now, wildly popular with the public, but loathed by the entrenched political classes. He saw his way out of the situation in Washington, D.C.

President McKinley's renomination was secure, and most likely also his reelection in 1900. But the vice presidency was open, as McKinley's vice president Garret A. Hobart, a New Jersey party functionary and pioneer baseball entrepreneur, had died in office. In those days, the presidential candidate did not have a role in the selection of a running-mate, that being the prerogative of delegates. Platt jumped at the opening and urged the selection of Roosevelt to be McKinley's vice-presidential candidate.

For years—in fact, since his childhood—TR's family, friends, and acquaintances had predicted he would one day be president of the United States. He was flattered, of course, but he also would fiercely rebuke such talk: no friend of his, TR said, should plant such dreams in his head; he did not want to be tempted to tailor his actions in calculation toward that ambition. In this instance, looking to 1900, however, Thomas C. Platt was not necessarily a friend; and, besides, it was the vice presidency Platt urged for TR, not the presidency.

Many of TR's vicariously ambitious friends saw the vice presidency as a dead end on his road to the White House. Roosevelt himself dreaded the prospect of presiding over the Senate, the lone duty ascribed the vice president by the Constitution. He considered the Senate a turgid debating society, and the vice president was proscribed from even joining the debate. The nation's first vice president, John Adams, had called the office the “most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.” A later vice president, John Nance Garner, famously described his office as “not worth a bucket of warm spit,” or words to that effect. TR was less than enthusiastic about consigning himself to oblivion. Henry Cabot Lodge, the same friend who had worked on TR's behalf for the earlier Civil Service and Navy Department posts, was the only friend who now encouraged Roosevelt to accept a spot on the ticket if offered. “The only way to make a precedent is to break one,” said Lodge.

Farmer William Jennings Bryan, in the cartoon from The St. Louis Globe-Democrat, says, “Hi there, you're ruining my crop!”

At first Roosevelt told Platt that he would rather be a professor of history somewhere than be vice president; besides, he had work to finish as governor. There were Republican leaders opposed to the idea as well, such as Senator Marcus Alonzo Hanna, Chairman of the Republican National Committee, and McKinley's longtime éminence grise. Mark Hanna had muscled past other veteran GOP bosses in national councils thanks to his friendship with McKinley, and was therefore an object of jealousy among members of the Republican party. So when Hanna counseled against TR's selection—“Don't any of you realize there would be just one life between that madman and the White House?”—even more local Republican bosses joined Platt's crusade, eager to frustrate Hanna.

But there was no need for backroom machinations, Platt's desperation and Roosevelt's disinclinations notwithstanding. There was a national groundswell of support for Theodore Roosevelt, arguably by now the most popular man in the country. Rank-and-file Republicans lauded him as an “eastern man with western ideas” (when “western” referred not just to his cowboy days but to the region's flirtation with Populist reforms), and even southerners appreciated his mother's plantation background. He was the Coming Man, the personification of the emergent, confident, vital America. TR attended the Republican convention in Philadelphia wearing a broad-brim hat, which delegates instantly dubbed a “campaign hat,” thinking it signaled TR's willingness to join the ticket. In fact he chose the hat to conceal an ugly, shaven head wound, sustained in a rock-climbing romp with his children a week earlier. Still, even if he had shown up in his union suit, delegates would have interpreted it as a sign of his availability as a candidate.

Despite the widespread supposition that Platt “put Roosevelt on the shelf” with the vice-presidential nomination (with other rivals to Hanna, like Senators Quay of Pennsylvania and Foraker of Ohio, trumping the GOP Boss), TR faced down Platt before the convention. He let the “Easy Boss” know that he desired to continue as governor, and would fight to the finish to continue in office. Platt relented. It was the true groundswell of enthusiasm from Republicans across the nation that persuaded Roosevelt during the convention that his larger duty was to join the national ticket.

J. Campbell Cory in The New York World envisioned Vice President Roosevelt presiding: “Gentlemen! The Senate will come to order!”

President McKinley reprised his “front porch campaign,” literally greeting small groups on his small front yard in Canton, Ohio. In contrast, TR offered himself “to the hilt,” just requesting of Chairman Hanna that his voice not be taxed, so that he might close the campaign with speeches in his own city. Roosevelt was indeed worked to the hilt, his special assignment being the heartland of America, between the Alleghenies and the Rockies. This included the home turf of William Jennings Bryan, again the Democrat candidate. Despite Bryan's scramble for a Nebraska colonelcy in the Spanish-American War, he had added fervent anti-imperialism to the 1900 platform, giving TR an extra reason to peg away at the Democrats.

McKinley and Roosevelt won an unprecented victory in 1900. Judge Magazine claimed partial credit, having popularized the GOP's cartoon icons of “Full Dinner Pails” of prosperity.

“Mr Dooley,” the Irish-dialect alter-ego of humorist Finley Peter Dunne, a popular and sagacious commentator on current events, observed, “ 'Tis Tiddy alone that's runnin'. And he ain't r-runnin'…he's gallopin'!” Accompanied again by Rough Riders, with brass bands playing “Hot Time in the Old Town” at every whistle-stop, TR criss-crossed the continent. By some reports, he traveled more than 20,000 miles. Sometimes he delivered a dozen speeches a day, attracting audiences totaling more than 3 million people.

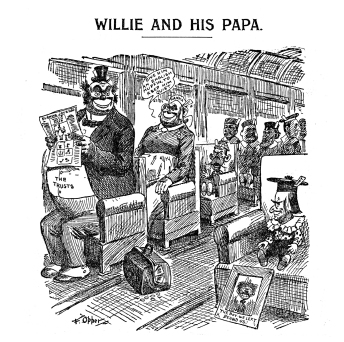

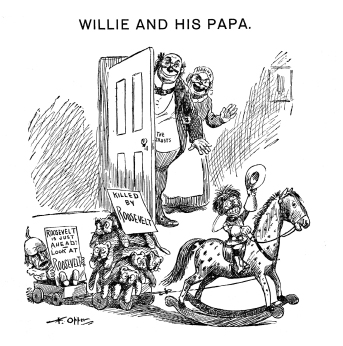

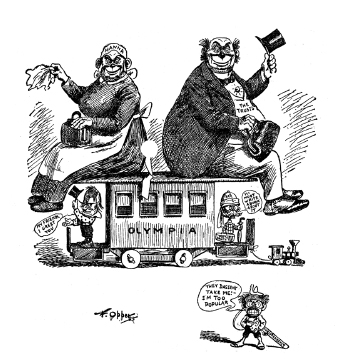

To Republicans still nervous about the economy, Roosevelt was of sound-money, gold-standard, high-tariff orthodoxy. To citizens squeezed by railroad monopolies or agricultural trusts, he had credentials as a reformer. Social conservatives were well aware of his stands against labor unrest and immigrant radicals. Patricians knew him as one of their own; so did ranchers and farmers, cowboys and hunters, scholars and sportsmen. In none of these roles did TR pander; in all—and more—he was in sympathy with these groups. Not since the 1884 presidential election had cartoons played such a role. Judge magazine invented an icon, the workingman's tin lunch pail, with a label indicating that prosperity and employment had returned: The Full Dinner Pail. The icon appeared hundreds of times in cartoons and on millions of GOP campaign handouts. In the Hearst press, cartoonist Homer Davenport (who later became TR's personal friend) drew vicious attacks, mostly on Roosevelt's hunting prowess—“Terrible Teddy, the Grizzly Killer.” Davenport's attacks on TR matched his grim cartoon depictions of Mark Hanna as “Dollar Mark,” whose foot invariably stood on the dried skull of Labor. F. Opper of Puck, known as the “Mark Twain of cartooning,” drew a long series of daily political cartoons based on McKinley and his running mate. “McKinley's Minstrels” depicted the president and his running mate in blackface; “Willie and His Papa” portrayed McKinley and Roosevelt as little boys in the care of a bloated father labeled “Trusts” and a nursemaid, Mark Hanna. Opper's cartoons were hilarious (often hitting the mark with depictions of little Teddy receiving more attention than Willie), and Edith kept a scrapbook of them. Reportedly Theodore also sought them out for his personal amusement.

The McKinley-Roosevelt ticket triumphed in November, winning the largest majorities for Republicans in a generation. The GOP's burgeoning constituencies were ecstatic, full of hope for the future. TR himself, however, was not particularly sanguine. He planned to take some law courses, to aid him when he presided over the Senate's debates.

He knew that life in Washington had its agreeable aspects, and the family would manage to live on the $2,000-a-year annual reduction from the New York Governor's salary. Roosevelt's friends, Henry Cabot Lodge chief among them, were still confident that Theodore, being Theodore, would break the chains of erstwhile obscurity that had overtaken his vice-presidential predecessors. Theodore would find a way.

So would Fate.

1898-1901: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

A WILLING GOVERNOR

AND RELUCTANT VP

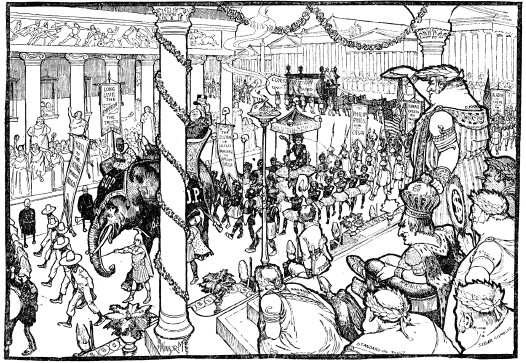

So popular was TR throughout America after the Rough Rider campaign, that cartoons began to appear about his presidential possibilities. This cartoon by Grant Hamilton in Judge appeared before Roosevelt had even been elected governor of New York.

Few people (including Tom Platt, the “Easy Boss” of New York politics) believed that Roosevelt would be a pliant governor. Cartoon by C. G. Bush in The New York Herald, 1898.

Even with the “good-government” reform crowd staying home and pouting, Roosevelt won the gubernatorial election in 1898. Representatives of GOP factions are united around him, and the field is scattered with vanquished Democrats. By Eugene Zimmerman in Judge, 1898.

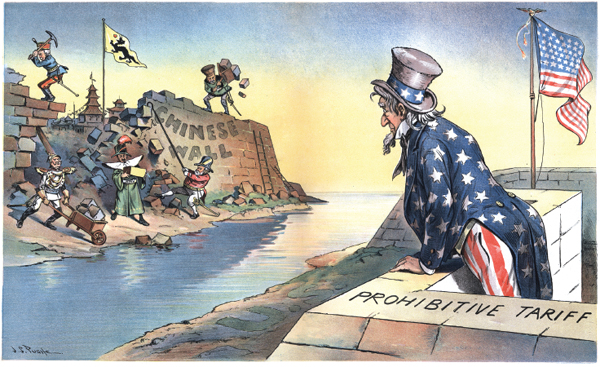

The parties in the 1900 presidential election ran on slogans, as usual (Democrats, vestigial Populist complaints and imperialism, Republicans, the “Full Dinner Pail” of prosperity), but there were serious issues that carried implications for the new century. One was the “protective tariff,” duties on imports, a burning issue for the previous generation. It generally existed to make foreign imports more expensive, not only to generate revenue but to encourage domestic industries. However, now that the U.S. was a robust economy, American industry and agriculture was interested in exporting. Other countries often retaliated with their tariffs against American goods. No major policy revisions were to take place for another decade.

The caption of this cartoon by J. S. Pughe in Puck was: “The Next Thing to Do.” Uncle Sam says to himself, “By Jingo! That reminds me that I've got a wall like that;—I'd better take it down, myself, before other people do it for me.”

“Now, Willie, we—re off. But what is that awful howling back there?”

“It's Johnny Hay. He's afraid his portable bawth tub will be left behind, and he's lonesome without that Pauncefote boy.”

Frederick Burr Opper was called by some “the Mark Twain of American Cartooning” when he left Puck magazine to draw for The New York Herald in 1898, and subsequently for William Randolph Hearst in 1900. Opper had illustrated books by Twain, Bill Nye, Eugene Field, H. C. Bunner, Edward Eggleston, Marrietta Holley, and other major humorists. When he joined Hearst he drew Happy Hooligan, Alphonse and Gaston, Maud the Mule, and many other strips.

Opper jumped into the 1900 campaign. Willie and His Papa was so popular that a reprint book was published in the United States and England; and the cartoons continued up to McKinley's assassination. Hearst syndicated the cartoons drawn during the presidential campaign to Democrat papers around the country.

“Trouble again, Willie? Well, what now?”

“Teddy says this is the way he is going to arrange the Inaugural Parade.”

“Now, Willie, we will rehearse our great railroad trip around the country. Nursie and I will act as ballast, Johnny Hay can be an English tourist in America, and Teddy, as you're not going, you can be the enthusiastic populace along the route.”

ABOVE: For Democrat cartoonists, like Winsor McCay of The Cincinnati Enquirer, McKinley's second inauguration represented the triumph of big business and imperialism. Four years after this cartoon was drawn, McCay was in New York City, drawing the classic comic strip Little Nemo in Slumberland.

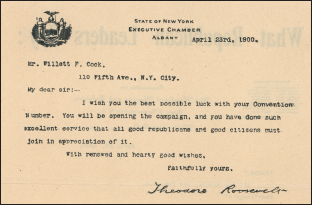

LEFT: A letter from Governor Roosevelt to the Republican cartoon magazine Judge. TR reportedly was a fan of political cartoons, even those at his expense. There are anecdotes of Edith keeping a scrapbook of cartoons about her husband (the critical ones prominently pasted to keep her husband's feet on the ground) but he reportedly was amused by F. Opper's cartoons in Puck and the Hearst press. Judge was a Republican organ that occasionally received subsidies from Republicans. The McKinley campaign's “Full Dinner Pail” slogan in 1900 was inspired by cartoons that began in Judge shortly after this letter was written.

1898-1901: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

OVER THE HORIZON: SPECTRE OF ANARCHY

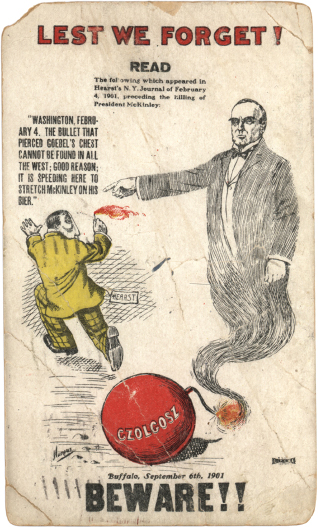

After the election of McKinley and Roosevelt (by a huge majority) and barely into the president's second term, he was assassinated by an anarchist (details, next chapter). Leon Czolgosz was the murderer, but many people placed ultimate blame on radicals in the mainstream of American life, like publisher William Randolph Hearst. His newspapers at the time espoused some radical ideas and solutions, but it specifically was a poem (supposedly written by Hearst staffer Ambrose Bierce) that predicted, more than outright advocated, that McKinley would be the victim of an assassin's bullet. The poem quoted over the amateurish cartoon on this contemporary postcard refers to the assassination of Kentucky governor Wilhelm J. Goebel.

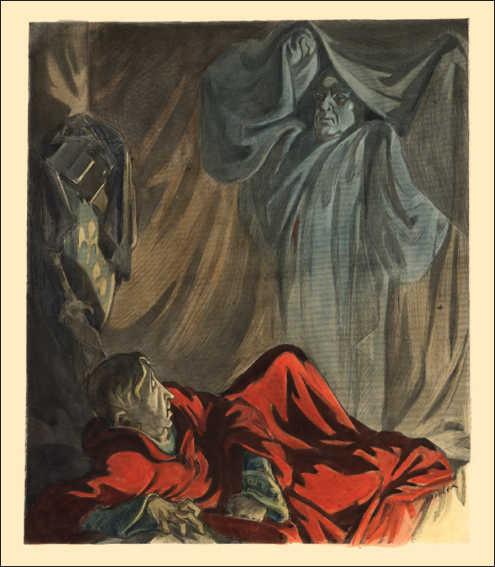

The public perception lingered that the Hearst papers' radicalism in general, and virulent hostility to McKinley in particular, contributed to the president's assassination. It affected Hearst's own presidential ambitions. This cartoon of McKinley's ghost visiting Hearst is reproduced from the original artwork.