CHAPTER 2

A Personal Banner

Life in Red Army Uniform

Fellow, you have the whole history of your life at the front on your chest.

—Vasilii Subbotin

In the summer and fall of 1941, hundreds of thousands of Red Army soldiers and commanders surrendered to the enemy or abandoned their uniforms while fleeing the battlefield. On August 16, 1941, Stalin issued Order No. 0270, in which he posed the question: “Can the Red Army tolerate cowards who desert to the enemy and surrendering or cowardly leaders, who rip off their rank and desert to the rear at the first sign of danger? No, we can’t! If we let these cowards and deserters have their way, they will very quickly demoralize the army and destroy our Motherland.”1 The army was on the verge of disintegrating, but many soldiers continued to believe in their duty to fight on. Kharis Iakupov, escaping encirclement in 1941, recalled: “There was only one thing that was considered reprehensible and punished: when someone among the soldiers stole through to their own having changed into civilian clothes. For us, the uniform was like a banner, and to abandon it was deemed to be an act as shameful as any display of cowardice.”2 Iakupov’s memoirs echoed Order 0270 and the image of uniform as a banner that had been developed in the Soviet military press during the war. This rhetoric was closely associated with a major change in style in 1943, when the army abandoned the uniform that so many soldiers had themselves cast-off or worn into German captivity, introducing a “new-old” uniform that reproduced late tsarist styles.3

Pogony (shoulder boards), a key old regime symbol, were recast as a point of pride: “Having put on pogony, Soviet soldiers and officers will carry them through the fire of battles as their own small, personal banners, which the Motherland solemnly gave them.”4 Along with pogony, a variety of decorations, many of which referenced old regime heroes, formed a rich text that was readable by both soldiers and civilians. As one correspondent noted in a profile of a heroic soldier: “you have the whole history of your life at the front on your chest.”5 In contrast to the uniforms worn by other belligerents, the Red Army did not wear distinctive insignia for individual units. The Red Army uniform truly was a personal banner, showcasing the wearer’s accomplishments.6

FIGURE 2.1

Soldiers M. V. Kantariia and M. A. Egorov with the banner of the 150th Order of Kutuzov Rifle Division, which was lifted over the Reichstag in Berlin, 1945. RGAKFD 0-291381 (V. P. Grebnev).

What follows is an ethnographic sketch of life in uniform in the Red Army. The reader will progress layer by layer from underwear to overcoat. In so doing, we will have a chance to explore often overlooked details of life in the Red Army, including the changing symbolism employed by the Soviet regime and soldiers’ reactions to it.

The clothing, heraldry, arms, and armor of ancient Roman soldiers and gladiators, medieval knights, Sioux warriors, and modern gang members are all readable texts that speak to the practical concerns of the roles their wearers fulfill and showcase the identity ascribed to and claimed by their wearer.7 Uniforms act as a “certificate of legitimacy,” guaranteeing that the bearer will submit to the rules and hierarchy of the institution that issued it.8 The proper wearing of uniforms, keeping them clean and in repair, is often more important than the articles themselves and includes the mastery of a particular etiquette.9 While uniforms are supposed to subsume identity, they are also separate from it. In saluting a commander, regulations demanded that soldiers acknowledge rank but not the name of the commander, as the soldier was saluting the commander’s uniform, and by extension the polity that the uniform represented.10

There were no “officers” in the Red Army in 1941. Formed as a revolutionary army, drawn from a society that had been purged of “exploiting” classes, authority centered on the role one fulfilled (e.g., kombrig—brigade commander), rather than rank as a status in and of itself.11 Titles such as lieutenant and major returned to the military’s lexicon on the eve of the war. In 1941, one could still see traces of the Civil War uniform echoed in soldiers’ headgear and insignia. As the war progressed, uniforms became at first more practical, then displayed an entirely different symbolism.

Proper attire could be hard to come by, as shortages haunted the Red Army throughout the conflict. Warehouses that had been concentrated in the western Soviet Union fell into German hands at the beginning of the war just as millions of new cadres had to be outfitted. The army was forced to make items last, replacing them less frequently. This led to criminal responsibility for the mistreatment of equipment, an eventual fine of 250 percent of the value of anything a soldier ruined or lost, and major efforts to keep items in service as long as possible.12 The most salient example of this was the recycling of uniforms and equipment, taking from the rear to give to the front and from the dead to give to the living. Various orders circulated demanding that scarce items such as helmets and overcoats be taken from rear-area soldiers to give to frontline troops.13 The dead were stripped of virtually everything useful: all equipment, shoes, belts, and overcoats, leaving only the uniform and underwear on the body.14 Rear-area soldiers wore secondhand clothing, given new clothes only when sent to the front.15 It was usually impossible to tell anything about the previous owner, but occasionally an indelible imprint was left on the inherited garment, such as coarsely sewn repairs of overcoats rent by shrapnel.16 Many garments outlived their wearers.

Soldiers on campaign traveled primarily on foot and spent most of their time outside or in structures that they built themselves with spades. Once soldiers were cold and wet, they might stay that way for days or weeks.17 They had limited access to water, and soap was issued at the rate of 200 grams per month for men or 300 grams for women.18 Opportunities to undress were rare.19 Naturally, soldiers were often filthy. Nikolai Chekhovich wrote to his mother: “Today was the first time for a whole month that I could scrape the mud off my clothing.”20 Under these conditions, the uniform became an outer layer of the soldiers’ bodies, a veritable second skin.

Underwear and Fellow Travelers

Underwear in the Red Army circulated even more frequently than other forms of clothing, as it was the most likely to be washed and changed, soldiers carrying a spare set in their packs.21 Underwear had a particular place in the Soviet project as part of its modernizing and civilizing mission. Underwear, soap, and bathhouses had been central objects to raise the cultural level of workers and peasants via improved hygiene in the 1920s.22 It was rare that anyone in the army had a chance to change their underwear. Some soldiers ritualistically changed theirs before battle, for good luck; others believed that changing underwear would bring bad luck.23 Regular changing of underwear happened when soldiers went to a bathhouse, which could be as often as once every ten days or as rare as every couple months.24 Predictably, lice and various skin ailments were a constant problem, and underwear tended to be dingy. One veteran mused: “Our shirts and drawers had become encrusted with salt, becoming gray-yellow. Our unwashed bodies stung from the bites of parasites.”25 Killing lice was a common pastime, as Lesin wrote, “If one asked what our company is doing, we would answer in two words: crushing lice.”26 Other soldiers recalled the lengthy process of popping lice with their teeth and nails or freezing them in the snow.27 Some old soldiers believed that lice emerged due to homesickness.28 In particularly desperate situations, lice could go from the personal banner to the division’s, as Boris Suris wrote in his diary, “We managed to save the division’s banner (the starshina of the Commandant’s Company carried it out on his back, and it got lice).”29 References to lice were censored from letters and newsprint.30 Lice could not be ignored at the front, and battles with lice took place primarily in bathhouses. These could be set up by the soldiers themselves or be traveling sanitary stations, where soldiers would have their clothing disinfected and deloused in special ovens.31 While they would get their uniforms back, chances were that they would get a different set of underwear.32 When soldiers did get a chance to undress, it could be a moment of revelation as to how much their bodies had changed. Chekhov-ich wrote his mother about how tan his face and hands had become, while Irina Dunaevskaia recalled the shock she felt when confronted with how much weight she had lost.33

Except for sailors, who had striped shirts of which they were immensely proud, the underwear issued to soldiers came in one of three types: flannel boxers, long white cotton drawers with a long-sleeved undershirt from May to October, or white flannel drawers with matching shirt from October to May. Ties were often substituted for buttons for the sake of speed of manufacture. For men in the ranks, this would be familiar and utterly unremarkable clothing. However, for female soldiers these garments could be vexing, as one veteran recalled: “We almost burst into tears, when they gave us those long johns.”34 Aesthetics aside, women were not provided with any specialized underwear such as bras and had to make do on their own, often from scrounged materials such as bandages.35 The army did not provide anything like sanitary napkins either. Women were left to informal measures to decide this problem themselves, as one sniper told the Mints Commission: “It’s very difficult during menstruation. There are no bandages and nowhere to wash up. The girls told the divisional Komsomol organization about this, and they told the medic to give as much bandages and wadding as we needed.” Others used the soldier’s personal first aid packet.36 Improvisation was a way of life in the army.

Underwear often became the victim of the regime’s shoestring budget, as soldiers traded clothes for food, leading to a shortage of underwear at the front and increased surveillance on the road to the front.37 Lacking a change of underwear meant disinfection was impossible.38 At least one soldier remembered how he and his comrades purposefully allowed lousy clothing to burn in order to receive fresh replacements, a practice occasionally endorsed by high-ranking commanders.39 Sometimes soldiers simply forgot to remove flammable items, such as lighters and grenades, from their pockets, emerging from the bathhouse to find the ashes of their clothing.40 Underwear, like the bodies of soldiers, was de jure the property of the state, but de facto under the control of the soldier.

Bottoms

Pants

Pants in the Red Army were of the jodhpur style and underwent less change than most other parts of the uniform in the course of the war. While at the war’s beginning it would be typical for commanders to have significantly higher-quality blue trousers and for everyone to be issued wool trousers in the winter and cotton in the summer, these practices largely gave way to more practical concerns. Rank-and-file soldiers received trousers with knee reinforcements. The army provided cotton pants in the summer and cotton padded pants in the winter. The increasingly diverse cadres of the army made sizing a major issue: one female soldier recalled that the padded trousers she was given fit “like a jumpsuit” and came up to her armpits. While men’s clothing was a necessity for female medics and snipers crawling across no man’s land, the desire to maintain a semblance of femininity was very strong; it was not uncommon for women to receive skirts or dresses for official functions and holidays or even to craft their own.41

Portianki and Boots

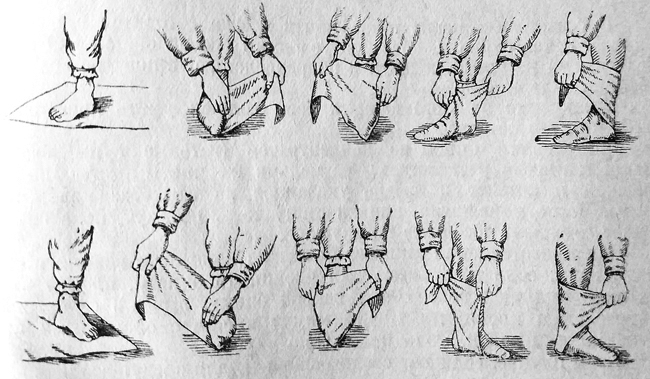

Red Army soldiers didn’t wear socks. Instead, they wore an ancient article from the peasant wardrobe. Portianki, or foot wraps, which came in winter and summer weights, were simply rectangular strips of cloth held in place by tension. While familiar to most peasants, they were alien to many urbanites: “For a long time the biggest problem remained portianki. If there happened to be even one wrinkle, your feet could be rubbed to blood, and commanders instilled in us that it was a crime to have blistered feet in the army.”42 Foot wraps were quite comfortable when properly wrapped, did not wear out at the toes and heel like socks, and could be turned around to a dry corner for multiple uses.43 A highly economical and traditional item, portianki were an exemplar of the Red Army’s mastery of doing more with less. The feet of soldiers who operated state-of-the-art tanks and planes were wrapped in the rags found in the bast shoes of medieval peasants.

FIGURE 2.2

Portianki from a Red Army manual. Posobie komandiru i boitsu strelkovogo otdeleniia (Moscow: Voenizdat, 1943), 123.

Once portianki were wrapped around the feet, one had to slip them quickly into whatever footwear they had been issued. These could be low boots with puttees (obmotki), which replaced jackboots as a stopgap measure.44 Some soldiers especially liked American-made boots received through Lend-Lease, though in the postwar period praising them became taboo.45 Puttees, or “three-meter bootlegs,” so-called because they were made of long strips of cloth, had a tendency to come undone at inopportune moments and seem to have been generally unpopular. Jackboots were not without their problems: “the top of the boot was made of artificial leather [kirza], the sole of rubber, and the nose of low-quality leather; even when oiled with blubber they would get wet in a hard rain.”46 Kirza (kozhzamenitel’ Kirovskogo zavoda) was first used in 1936–1937 and authorized to replace leather goods in 1940, as a way of stretching resources for the expanding army.47 Some soldiers tried to use captured German boots, but many complained that they were too tight at the ankle and too wide at the top, one soldier recalling that he had to cut himself out of a pair of captured German boots and retrieve his own worn-out boots.48 Some soldiers sported boots made of green cotton tarpaulin for summer months.49 Commanders were authorized to wear “chrome boots” of shiny leather. Finally, for extreme cold, Red Army personnel were issued valenki, traditional peasant boiled-felt boots.

Seasonal change was often the worst time for soldiers. As winter turned to spring, felt boots that were ideal for extreme cold became sponges absorbing frigid water, leading to increased cases of frostbite.50 As fall turned to winter, people froze in thin kirza boots. The situation in spring and fall frequently aroused the scorn of inspectors, as they observed barefoot soldiers or soldiers wearing rubber antichemical stockings in the absence of adequate footwear.51

There was no single piece of the uniform that was more important from a practical perspective than boots. Not having proper footwear could lead to unimaginable suffering when one was constantly exposed to the elements and walked everywhere. Boots too large, too small, or too worn out led to suffering. Chekhovich wrote his mother about the declining fortunes of his boots, which “held, held, and then started leaking” despite “nearly daily repairs,” until finally he lamented “[I] really rubbed my feet raw—till they were bloody… but kept going.”52 The army was deeply concerned with reserves of boots and their repair, dedicating considerable attention to them.53 Boots were supposed to be cleaned to a bright shine at all times.54 Boots became a significant part of the military’s civilizing process, for they were the article most quick to get dirty, the hardest to keep clean, but also the most practically significant. As the emphasis on the soldier’s appearance increased, boots were expected to be cleaned and shined, especially when soldiers were interacting with civilians.55 Boots were constantly an issue, right up to the end of the war, and often replaced under combat conditions. One soldier, on receiving a new pair of boots in Berlin, autographed his old ones adding “got to Berlin, 1945” and threw them into a tree as a record of his achievement.56 Like everything else a soldier wore, boots were ubiquitous yet personal. Boots were the part of one’s uniform most likely to cause pain and the first thing taken off the dead to give the living.57

Tunics, the Personal Banner

Government Symbolism and the Tunic

Unlike boots, tunics were not recycled from the dead to give to the living. A tunic (gimnastёrka) was expected to be worn by a soldier for six months, being replaced with the winter or summer issue of clothing, and was often salty from sweat and faded by the sun.58 Tunics underwent the greatest amount of change during the war. As the primary uniform item, the tunic was the main text of a soldier’s biography. It was the garment that carried insignia and to which all medals and orders were affixed, serving as a soldier’s personal banner. The tunics themselves were among the simplest uniforms issued by any army to its combatants—simple pullover shirts made of cotton or wool, with elbow patches for enlisted men.

There was a specific technique to wearing the tunic. A belt was required to give the loose fitting shirt a smart appearance, and soldiers folded the garment in the back so as not to create unattractive wrinkles in the front that could cause blisters. Not a single button or hook could be undone without the commander’s permission. A fresh, white collar liner (podvorotnik) was to be sewn in every day. Without it a soldier was out of uniform.59

The shortages brought about by the war in both men and material made being stylish difficult, because the army was forced to simplify uniforms, including the authorization of nonuniform buttons (often simply stamped steel) in November 1941.60 A report from September 1941 lamented that uniforms were usually incorrectly sized, shrank one size after the first washing, and poorly fitted the growing number of older soldiers in the ranks.61 As the war continued, uniforms would be recycled from the wounded, and soldiers in training wore exclusively secondhand clothes, fresh tunics being reserved for those at, or en route to, the front.62

FIGURE 2.3 Guards Senior Sergeant V. I. Panfilova, Eighth Guards “Panfilov” Rifle Division (named in honor of her father, I. V. Panfilov), 1942. RGAKFD 0-286566 (V. P. Grebnev).

In 1941 tunics still retained traces of the Civil War, bearing the insignia for branches of service (infantry, artillery, cavalry, etc.) devised during that conflict. Two chest pockets were to hold the soldier’s documents, a first aid packet, and assorted sundries. Rank, in the form of red enameled geometric shapes, and branch of service were worn on the folding collar in vivid colors— raspberry red with black piping for infantry, medium blue with black piping for cavalry, black with red piping for artillery, and so on. Brass pips identified branch of service—a tank for armored troops, crossed shovels for engineers, and the like—making soldiers easily distinguishable. Commanders had additional piping on the cuff in their branch of service color and chevrons on their sleeves; political officers sported a gold-braided Red Star with hammer and sickle on their sleeve.

While quite attractive, in the immediate aftermath of the Winter War these insignia were found to be too conspicuous on the battlefield and were replaced in August 1941 by “defense collar tabs” of olive drab with rank and insignia in muted green.63 The flashy insignia continued to be popular. V. E. Ardov wrote to Stalin explaining that commanders saw the colorful insignia as a privilege that “inspires people, arousing respect for them from the population, [and] decorates the difficulty and danger of battle service.”64 The desire to be stylish could overtake other concerns, including safety. Stalin underlined “insignia” in Ardov’s letter and a dramatic change in soldiers’ appearance would mark the Red Army’s shift in fortune and turn westward.

Pogony and the “New-Old” Uniform

On January 6, 1943, less than a month before the German surrender at Stalingrad, the Red Army received an order fundamentally changing its uniform. The new uniform featured a standing collar with two buttons. Pockets would no longer be seen on soldiers’ tunics and would be inset on officers’ and sergeants’ uniforms. This new model looked even more like a traditional peasant’s tunic than the early war uniform, but this was not its primary association. The “new-old” uniform would be familiar to Soviet citizens, as it was a return to late tsarist uniforms, including the previously hated shoulder boards.65 The return of pogony was announced at a moment when victory at Stalingrad was inevitable. However, the decision to introduce the new uniform had been made in October 1942, a period that General Vasilii Chuikov, commanding the Sixty-second Army at Stalingrad, described as “the most horrible period of the enemy’s assault.”66 Their introduction diverted resources from civilian clothing and underwear production, which were already in short supply.67 Since the outbreak of the war the army had been simplifying all of its equipment in order to stretch resources. Clearly, this change in symbolism took precedence over materialistically pragmatic concerns. Pogony would mark a new relationship to authority and the Russian past and become a symbol of a successful, reborn Red Army.

There had been several previous attempts to give the army a makeover. In 1940 the state looked to create more gallant peacetime uniforms (many of which echoed those of 1812), and in 1941 a distinctive uniform for elite Guards units was considered.68 According to David Ortenberg, the editor in chief of Krasnaia zvezda for most of the war, Stalin vacillated on whether or not “to bring back the old regime” by introducing pogony. Eventually he was convinced that the new-old uniform would help motivate soldiers, many of whom had no memory of the old order. Stalin demanded that journalists promote pogony as a symbols of order and discipline, declaring that “we are the inheritors of Russian military glory.” Top Soviet officials apparently even scoured museums to find old pogony.69 Rank would be indicated by the number of stripes for soldiers and the size and number of stars for officers. The branch of service symbols moved from collar to shoulder board with trim around the pogony in the prewar color scheme. The new pogony would come in everyday (peacetime and rear-area) and field (combat) versions, the former of which would even revive golden pogony for officers!

A Krasnaia zvevda article from January 1943 explained the timing of the soldiers’ makeover in terms both pragmatic and historical, dismissing the idea that “it would not seem to be the time to become preoccupied with the soldier’s appearance”: “The introduction of pogony, which clearly express the subordination of juniors to seniors in service, strengthening the authority of leaders, has a principal and important meaning… And the fact that they have appeared on the shoulders of Soviet warriors at this moment, at the climax of the struggle, makes them a doubly honorable sign, forever linked with the legendary battle for the honor and independence of the beloved fatherland.”70 Pogony were markers of both increased military effectiveness and historic change. They also happened to be one of the preeminent symbols of the old regime. Boris Kolonitskii, an expert on symbols in the Russian Revolution, has pointed out that in 1917 the degree of antipathy toward pogony was a reliable indicator of a unit’s “degree of revolutionization.” It was not uncommon to demand the removal of pogony in the early phases of the Revolution or to drive nails through the pogony of captured White officers during the Civil War. Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak, one of the leaders of the White movement, explained to his Bolshevik captors shortly before his execution that he saw pogony as a “purely Russian form of insignia.” He also saw them as a sign of discipline and a guarantor of performance by the army, which “when it was in pogony, fought, and when the army changed its spirit, when it took off pogony, this was connected to a period of the greatest disintegration and shame.”71 Ironically, the Main Political Directorate of the Red Army (GlavPURKKA) and many Soviet commanders would come to agree with Kolchak a few decades after the Bolsheviks shot him. General Chuikov told a historian in Stalingrad that “The factor of ambition [chestoliubie] remains… the title ‘Guards’ and similar things, the titles, given to our heroes, pogony—you think that Stalin isn’t taking this into account?”72

The day after the return of pogony was announced, Aleksandr Krivitskii published a lengthy article in Krasnaia zvevda concerning the sea change in the regime’s symbolism. After a lengthy history of uniforms in Europe and Russia, Krivitskii explained that during the Civil War the Red Army refused the uniform that its enemy wore, but now, having matured, it could wear the “signs of military dignity” that decorated “the uniform of the Russian Army in 1812” all the way to World War I.73 In one of the few references to the Civil War in propaganda about pogony, Krivitskii dismissed what had been a fundamental difference between Whites and Reds as “water under the bridge.” Instead, he emphasized the Red Army as the descendant of Russian military traditions in a way consistent with propaganda centered on the Soviet edition of romantic Russian nationalism, continuing a trend started in the 1930s.74 The preeminent event in that tradition, the Patriotic War of 1812 in which Russian forces defeated Napoleon, is invoked, with pogony providing a material link to history that was repeating itself. Propaganda portrayed Red Army soldiers as the descendants of traditional Russian heroes such as Aleksandr Nevskii, Aleksandr Suvorov, and Mikhail Kutuzov, while occasionally paying heed to (also long deceased) Civil War figures such as Vasilii Chapaev, Nikolai Shchors, and Mikhail Frunze. The Soviet Union was no longer portraying itself primarily as a young regime oriented toward world revolution but rather as something like a nation with ancient roots that had its potential unchained by the Revolution. At the same moment that the soldier’s uniform became more national in form, the motto on military banners changed from “Workers of the World Unite!” to “For Our Soviet Motherland!”75

As the Soviet state began to resemble a nation-state more closely, its army followed suit. The authority of commanders was strengthened. Dual command, the practice by which orders given by a commander needed to be cosigned by commissars, was repealed, giving commanders full authority. The term “officer” was reintroduced with a corresponding emphasis on hierarchy. Before 1943 the army was divided into privates, junior commanders (which included both sergeants and lieutenants), supervisory cadres (nachal’stvuiushchii sostav) and command staff.76 Beginning in 1943 the army was divided into privates, sergeants, officers, and generals.77 More than a simple change in phrasing, classification had become more rigid and new divisions were made between classes of cadres.

The year 1943 is often cited as the time by which the Red Army had learned to fight.78 The cadres who came into the army in 1941–1942 were often poorly trained because crises at the front led to minimal training. Many soldiers learned how to fight at the front. By 1943 collective experience had accumulated, and the situation at the front had stabilized to the point where soldiers could receive more training and increasingly impressive weapons, a process detailed in chapter 5. Liberated civilians and German prisoners noticed the new-old uniform, as General Andrei Mishchenko noted in February 1943, the entrance of troops wearing the new uniform made an extraordinary impression. German prisoners exclaimed: “this isn’t the Red Army that we beat in 1941. Now that army is no more—now the tsarist Russian army has taken form.”79 The new uniforms were the mark of a new army, one that was mastering its trade and would be advancing west rather than retreating east.

Soldiers were permitted to wear out their old uniforms with attached pogony until they were issued new tunics, and a variety of hybrid uniforms appear in photographs. (See figures I.1, 4.3, 4.19, and 5.4.)80 The issuing of pogony was supposed to be accompanied by an improvised ceremony, which served as a reaffirmation of the soldier’s responsibilities before the state and became an unforgettable moment in the soldier’s life. Aleksandr Lesin recorded that he was given his pogony at the Kalinin Front “not exactly in a grand manner, but not without words of encouragement.”81

With the new uniforms came new responsibilities that went beyond rhetoric. The term “the honor of your uniform” (chest’ mundira), which before had been associated with tsarist officers, entered Soviet rhetoric. At the front troops honored their uniform with daring deeds, and in the rear by being a model citizen.82 Wearing pogony “any little thing” that a soldier did was “of serious importance.” Soldiers’ behavior and appearance was subjected to intense scrutiny.83 This was more than simply lip service, as memoirs and diaries record how soldiers were harassed and arrested for improper appearances or had their pay docked for swearing from 1943 on.84 The growing cult of the uniform was one of the most publicly recognizable aspects of the campaign to professionalize the Red Army and create a separate caste of officers with corresponding hierarchical relations.

Improving the appearance and bearing of officers was part of the perpetual Soviet concern with “raising the cultural level” of what was still an overwhelmingly peasant society. Officers were permitted to wear a special uniform (kitel’) similar to European uniforms (they buttoned all the way down the front) and were encouraged to order clothing from tailors.85 Offi cial propaganda stated that in the old army: “The authority of a Russian officer was based on his higher cultural level… In our Red Army officers are required to be of an even higher cultural level.”86 Soldiers and officers alike complained about the low cultural level of the army’s commanders. Some officers took it on themselves to write tracts reminiscent of nineteenth-century etiquette manuals, including how best to blow one’s nose, chew food, use knives and forks, drink, spend money, and interact with the wives of one’s superiors. These books so enraged General Aleksandr Shcherbakov, head of the Red Army’s Main Political Directorate, that he forbade their publication, stating these texts “interpret in a perverted and philistine spirit questions of morality and etiquette, soldierly education, [and] military honor and often propagandize views alien to the Red Army.” Shcherbakov reminded his subordinates that the purpose of discipline was to fulfill goals of the military, not to recreate the officer corps of the old regime.87 Confusion over the meaning of pogony was not limited to the authors of ill-fated etiquette manuals, as many soldiers themselves were at a loss in their attempts to understand these new “small, personal banners.”

Soldiers React to Pogony: The Empire’s New Clothes

“They are introducing pogony. We are perplexed by it all [My vse nedoumevaem],” Boris Suris laconically wrote in his diary in January 1943.88 Suris was far from alone in not knowing what to make of the “new-old” form. Even top officials felt awkward at the sight of pogony in January–February 1943.89 Pogony soon became ubiquitous, and everyone adjusted to them, but initial responses varied.

Guards Lieutenant Rafgat Akhtiamov, a Tatar from a remote village, was very enthusiastic about the new uniform, stating “I have such clothing now as no one in the village ever dreamed about” in one letter and “the government has dressed us very well, I only want to go visiting, that’s how pretty the new uniform is” in the next.90 Akhtiamov, whose father had served in the Russian Imperial Army, betrayed no sense of the political in his letters home and seemed genuinely enthusiastic about the new uniform from an aesthetic point of view. As the representative of a national minority, he could have had reason to interpret this shift as a return to tsarist norms that marked his people as second-class citizens, but he reveals no sense of worry. Lev Slëzkin, a Muscovite, remembered that soldiers were at first indifferent to the introduction of pogony, but that once they received them “many were quite satisfied… not so much due to the restoration of an external link with a tradition that had disappeared for a quarter-century as that pogony gave the wearers a certain swagger and bellicosity.”91 The ranking political officer of the Seventy-ninth Guards Rifle Division told the Mints Commission that soldiers enthusiastically awaited pogony, a sea change from 1918–1919: “Even before they got their pogony, Red Army men sewed straps for pogony on their uniforms. Everyone couldn’t wait to get their pogony. Some joked that they felt like plucked chickens without them.”92 Pogony made soldiers’ shoulders look broader, creating a more masculine appearance, but not everyone perceived them as simply attractive elements of their uniform.

Many soldiers saw the return of pogony exactly as Red Army propaganda presented it. Senior Lt. Bogomolov lauded them as “a great thing for the strengthening of discipline,” that gave “an even more martial countenance” and recalled “our forefathers.” Another officer thought it simply impossible that soldiers could remove such a uniform and dress in civilian clothes, as had been common in 1941. For some, the fact that the government could afford to undertake such a clearly expensive and not apparently necessary campaign in the midst of war was a positive sign.93 David Samoilov saw “the appeal to tradition” in general as a sign of “the entry of our government into the moment of maturity, the classical stage of development.”94 For many the national and traditional was either more attractive than, or in no way contradictory to, the ostensibly socialist society they were fighting for.

Others were confused by or even opposed to pogony. According to reports by NKVD agents, several saw pogony as signs of the bourgeois world, as something that the capitalist allies of the Soviet Union had forced on the socialist state. Others were simply disgusted by the return of the old, musing that old forms of address such as “Lord” (gospodin) and symbols like the double-headed eagle would reappear. Some took this as a sign that churches would be reopened, old hierarchies would reappear, and the Soviet Union would become a capitalist country. One soldier even detected a hint of fascism: “the fascists wear pogony. Soon they will clip on pogony and we will be eternal soldiers.” Others bemoaned the low cultural level of Soviet officers as compared to tsarist cadres, “the old officer of the Russian army was a most cultured person, and ours—simply a disgrace [sramota].”95 A sense of inadequacy before the heroic past overtook a sense of inferiority before enemies for some, while others still found the taste of the old regime unpalatable. Some were disturbed by the reintroduction of pogony as a sign of growing nationalism, as Russian national tropes were increasingly becoming a standard of propaganda.96 In the end, regardless of their attitudes toward pogony, as soldiers they had no choice but to wear them.

Despite new uniforms and rhetoric, soldiers continued to live in filthy conditions and wear their clothes for extended periods of time. While recovering from a wound in August 1943, Boris Suris reflected in his diary about the lack of respect shown by soldiers to officers. While there was much talk of “the honor of an officer, of the dignity of the commander,” it was useless “when so many of our commanders go around in low boots with puttees or boots that have been torn to shreds and patched up a thousand times, in salty and sun-faded uniforms.”97 Even the new uniform would fade and become covered with mud.

The dramatic change in the army’s fashion caught a variety of people— those on occupied territory, former White Guards, and Soviet laborers deported to work in the Third Reich—unaware. Liberated peoples did not always recognize Red Army troops, some even asking, “Are you Soviets or Germans?”98 The confusion caused by pogony did not end at the moment of liberation. Some recently liberated civilians asked whether there was “a new aristocracy” consisting of generals, and if “after the introduction of pogony there are no longer Communists or Komsomol members in the USSR?”99 While these men and women had been under occupation, a return to tradition that had begun before the war came to fruition, leading to a new banner, new uniforms, and eventually, in 1944, a new anthem. The new “Anthem of the Soviet Union” spoke of “Great Rus’” rather than the Internationale’s “whole world of the starving and enslaved.”100 Even some Russian émigrés who had fled the Revolution gazed in wonder at the Red Army’s pogony.101

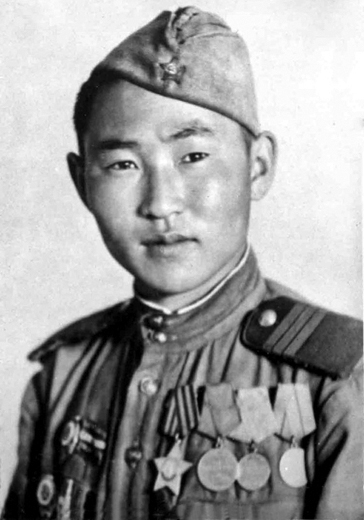

FIGURE 2.4

Guards Senior Sergeant Bato Damcheev, most likely in the winter or spring of 1945, www.ww2incolor.com/soviet-union/soviet_1.html.

A new understanding of what it meant to be Soviet was emerging, one with a new relationship with the past and a clear ethnic hierarchy in which Russian was assumed to be not only the lingua franca but also the common culture, similar to German in the Hapsburg Empire. New forms of social differentiation also came to the fore in the new officer class, elite Guards units and highly decorated soldiers. The collections of decorations a soldier earned became the main text of their personal banner.

Decorations: The Emergence of New Icons

As a heroic past was increasingly made relevant and manifest, Red Army soldiers were encouraged to become heroes, modeling themselves on historical figures and repeating contemporary feats. The military press was filled with accounts of miraculous acts of heroism, much as the prewar press had lauded the exploits of shock workers, border guards, and polar explorers, and the Red Army used decorations as didactic tools to encourage bravery.102 Both the actions of soldiers who had earned various decorations and the decorations themselves were to serve as means to raise the consciousness of soldiers: “We must teach others using the example of heroes; we need to tell the fighters more often about the best people, selflessly struggling for the Motherland, and drive these stories into the hearts of Red Army men.”103 This obsession with inspiration led Soviet leadership to research the tsarist system of awards. The military press later ran articles about the history of military decorations in Russia, going all the way back to medieval chronicles.104 Alongside these articles, lists of those awarded with various decorations and stories of how soldiers received them were standard reading throughout the war. Inspiring soldiers to earn medals was one of the ways that the government tried to mitigate the lack of training and equipment it provided soldiers in the war’s early days and eventually created a particular culture of decorations in the Red Army.

The Red Army’s practice of wearing decorations at all times was unusual. US combat soldiers were famous for their apathy toward decorations. Several armies wore small ribbons in place of medals themselves and even those only on their dress uniforms, making their uniforms a text that few could read.105 Although the Red Army officially went over to wearing just ribbons rather than medals in 1943, photographic and archaeological evidence shows that the wearing of medals was common until the final days of the war. In the Red Army decorations were part of the everyday uniform and a point of pride for soldiers.106 People could be prosecuted for wearing medals they had not earned or for losing their medals, as German spies made extensive use of decorations in order to more convincingly pass themselves off as Red Army soldiers and officers.107 Medals gave a soldier authority.

At the beginning of the war medals were quite rare. Decorations were most often issued on holidays and could take months or years to find their recipients.108 As of September 29, 1942, 69,436 medals had not found their recipients, who had either been killed, wounded, or transferred to other units.109 That month, Oskar Kurganov, a war correspondent for Pravda, noted that after waiting several months for a decoration “occasionally the person getting the award forgets for what exactly they were decorated, and those around the soldier don’t know anything about it… It’s clear that the power of such decorations to stimulate is highly insignificant.”110 As the war continued, the process of awarding medals was simplified and the government encouraged officers to award their subordinates more generously.111

By 1944 the army created standards for awarding some decorations simply for the number of years one had served, overwhelmingly benefiting career officers.112 One Polish civilian observed in late 1944, “In no other army have I seen such a profusion of decorations. Every private had at least three, while the officers had at least a whole row, sometimes one on the left side and one on the right.”113 Decorations came in several genres and were awarded for everything from baking bread and surviving wounds to feats such as destroying enemy tanks or seizing enemy banners. There were a variety of badges, awarded before and during the war, that formed an ever expanding list. Para-troopers received a badge for learning how to jump. “Excellent” awards were given for professional competence. For example, one could earn the “Excellent Cook” badge for “systematically” doing such things as “quickly providing hot food and tea” and “using local resources to provide vitamins and greens,” as well as properly camouflaging a field kitchen.114 Within certain frontline communities, these decorations were highly prized, as they were given out for one’s holistic talents and professionalism, rather than for a feat of heroism.115

The most common badge was issued to whole units and granted major privileges. This was the badge created to distinguish Guards units, elite military formations that had earned their status through combat exploits. The first Guards units were recognized in September 1941, and from May 1942 soldiers in Guards units earned double pay, Guards commanders received 150 percent of a commander’s base pay, and all Guards personnel had access to better clothing, equipment, food, and weapons as well as the title “Guards” added to their rank. They also had the right to return to their unit after being wounded, enjoying a much more stable social world.116 The ideological underpinnings of Guards units were not the Red Guards of the October Revolution, but the elite Guards Regiments of the Russian Imperial Army. Guards soldiers took pride in their privileged status, and Guards units received the most physically fit and politically mature replacements.117 In a massive, largely anonymous army where cadres moved around constantly, the Guards badge gave soldiers a sense of corporate pride and belonging, as well as a means to make claims about their own worth.

Similar to Guards Badges, in that they were issued en masse, were campaign medals. These were received by every surviving participant in a battle: for example, for the Defense of Moscow (over 1,000,000 awarded) or the Defense of Leningrad (over 1,470,000 awarded). The most widely issued campaign medal, Victory over Germany, was issued to everyone in the army in 1945, over fifteen million people.118 These medals could take months and sometimes years to reach soldiers and did not imply distinction on the battlefield, merely presence. Spotting a campaign medal could be a moment of fellowship, as two soldiers who served at the same battle swapped war stories and made newly arrived soldiers jealous. After the war, some veterans wore these medals on trips to the relevant cities to garner special treatment.119 While Guards badges and campaign medals were about collective feats, most decorations noted personal accomplishment and sacrifice.

In July 1942 the Red Army introduced wound stripes to be awarded to all personnel who had been injured since the beginning of the war. Coming in two varieties—red for light (flesh) wounds or gold/yellow for serious wounds (broken bones or compromised arteries)—wound stripes served two purposes. They proved that people could struggle and survive despite injuries received at the front and celebrated these survivors as heroes to be emulated. Every wound had a story, and surviving the enemy’s fire gave a soldier authority. In one propaganda piece a soldier uses his wound stripes to discuss his transformation from an enthusiastic but foolish greenhorn (saying of his first stripe “I don’t respect this one”) to an effective warrior respected by all.120

Several medals were issued in the Red Army for personal accomplishments, such as For Valor and For Combat Service. As the war continued and medals became more common, they seem to have become almost an expected accoutrement.121 Medals were proof that people had done their duty, an individual mark that they had done something of note for the war effort, and something to write home about. Those without medals often felt a sense of shame. Lt. Vladimir Gel’fand confided to his diary in August 1944: “At war fiasco after fiasco. No orders. Not even a medal, at least for Stalingrad. I have no reputation… The earth crumbles beneath my feet.”122 Among the rank and file, the pressure to earn medals was perhaps less urgent, but still palpable. Mansur Abdulin recalled: “Here soldier psychology is simple: the war has been on for two years, and after Stalingrad it is somehow particularly shameful to not have at least one medal on your chest. ‘What have you been doing there,’ one wonders, ‘if you haven’t earned any decorations?!’”123 This sentiment could be used to pressure soldiers directly. At the end of the war Lesin recorded an officer scolding a young lieutenant—“The war is ending, how are you going to remain without any orders?”—before sending him on a particularly dangerous assignment.124 Interestingly, the culture of medals most similar to the Red Army’s was that of the Third Reich, which also used medals as a stimulus that included peer pressure, created a complicated system of decorations, and called on its soldiers to wear their medals as part of their everyday uniform.125 Soviet leadership researched both German and tsarist systems of decorations in late 1942, a period of expansion of both the system of decorations and the volume being issued.126

Medals proved you were a man, but orders made you a man among men (even if you were a woman). Orders were a higher form of decoration, reserved for the truly exceptional. Decorations existed in a hierarchy, and the medals that Red Army personnel received were to be worn in a manner that displayed this hierarchy with the highest decorations displayed most prominently.127 Medals and chest badges were less significant than orders, which were worn above other decorations. Made of precious metals such as silver, gold, and platinum and studded with enamel or jewels, orders were an expensive item for the government to manufacture, yet some were made in mass quantities. The most commonly awarded order, the Order of the Red Star (cast of silver and enamel), was issued more than 2,860,000 times during the war.128

That the Soviet government was willing to expend such extensive resources on decorations speaks to the emphasis that they put on decorations as a stimulus. The statutes of these orders could be very specific and were published in the military press. For example, a soldier could earn the Order of the Patriotic War for such acts as destroying three to five enemy tanks or five enemy artillery batteries, being the first to enter and destroy the garrison of an enemy bunker that had pinned down an advance, and so on.129 Many of the decorations conceived during the war were instituted in the spring and summer of 1942, when the Red Army was clearly losing.

The government continued to create new orders as the war continued, instituting a slew of them between 1942 and 1945. A major means of connecting the Red Army with the heroic Russian past, orders explicitly harkened back to the great men of Russian history, bearing the names of leaders such as Aleksandr Nevskii, Suvorov, Kutuzov, Pavel Nakhimov, Lenin, and even the Ukrainian hetman (Cossack military leader) Bogdan Khmel’nitskii. Each historic figure that had an order named after them also had a movie made about them. After being awarded an order, one became a “cavalier” of that order, something akin to an ancient knight. Orders also carried the concrete privileges of an ordenonosets—“order bearer.” Every ordenonosets was entitled to a free yearly round trip by rail or boat to anywhere in the Soviet Union, free use of trams in cities, a reduction of taxes and utility bills, and a reduction of time before pension by a third. All of these privileges were announced to the public and would be enjoyed by their family after the bearer’s death.130 Stakha novites, polar explorers, and marshals had commonly received orders in the prewar period; the new cadre of war veterans swelled the ranks of ordenonostsy.

Many orders were awarded exclusively by rank. For example, the Order of Victory—a diamond-studded platinum star—could be awarded only to front commanders and marshals for coordinating and prosecuting a massive offensive. The Order of Suvorov existed in three degrees: the first degree for officers commanding whole fronts or armies and their staff; the second for commanders of corps, divisions, and brigades and their staff; the third for regimental, battalion, and company commanders.131 The Order of Glory was available only to soldiers, sergeants, and pilots and came with an immediate rise through several ranks, a 5–15 ruble monthly bonus in pay, a 50 percent reduction in time to pension, and free higher education for the bearer’s children. This order was conspicuously modeled after the St. George Cross, a combat award from the Russian Empire that was often allowed to be worn in the Soviet period.132

Orders could also be awarded to military units, factories, ships, newspapers, republics, and cities, making them both corporate and personal awards. Any corporate entity would have its title read at official functions, and military units would often receive honorific titles for towns they had liberated or captured (“Fifty-second Riga-Berlin Guards, Order of Lenin, Orders of Suvorov and Kutuzov Rifle Division”). These decorations were inscribed on the unit’s banner just as soldiers wore their individual medals on their tunics.133 The titles and decorations a division carried told a story of its feats that was used to inspire new soldiers in the unit.134

The highest award (technically a medal), Hero of the Soviet Union, could be won (often posthumously) by anyone of any rank and was routinely given to pilots for completing twenty-five missions. The Gold Star earned its recipients immortality, as they automatically received an Order of Lenin and their story became the subject of media attention. Should bearers win a second Hero title, their busts were to be cast in bronze and displayed in their home-towns.135 During the war, more than 11,500 soldiers received this medal, 104 twice and 3 thrice.136 People of humble origins, such as Aleksandr Matrosov and Zoia Kosmodem’ianskaia, who sacrificed themselves in the war came to share a place in the pantheon of the conflict’s mythology with men of stature, such as Stalin and Marshal Georgii Zhukov.

Due to their transformative power and biographical importance, medals were rarely removed. Part of the punishment of being sent to a penal unit was the retraction of all decorations and rank, an act made public by reading the punishment and removing decorations in front of one’s comrades.137 When going on reconnaissance, medals and all forms of identification would be surrendered.138 Medals and orders were to be taken from the dead and sent to their families or museums, as relics of the fallen.139 When soldiers were buried far from home in unmarked graves, medals were often the only remains a family received. During the funeral procession of a high-ranking officer each of his orders would be carried by an officer on a separate pillow behind the hearse.140

Decorations soon entered the lexicon of “speaking Bolshevik,” as people writing letters to various bureaucracies would be sure to mention medals they had been awarded to legitimize their demands.141 For those who had been prisoners of war, a decoration could be “a pass to life,” erasing their perceived guilt.142 However, the manner of speaking Bolshevik was changing, as the language had come to incorporate references to a heroic past that had become much more ancient and that was repeating itself. The medals and orders themselves often made reference to a heroic past that posed Russians as an extraordinarily gifted nation, while their primary purpose was to identify and promote outstanding individuals as exemplary models.

Many desired further distinction. People wrote Stalin and Mikhail Kali-nin with various suggestions for new awards. Before campaign medals were instituted, soldiers wrote in recommendations with elaborate schemes for Defender of Moscow and For the City of Lenin medals.143 Snipers wrote Kalinin suggesting that they be given a chit to dangle from their Sniper badges, indicating their number of kills.144 In May 1942 V. Markevich wrote Stalin with three suggestions: to devise medals for participants in the Russo-Japanese War and World War I; to devise medals for participation in the Civil War and Winter War; and to create some sort of distinctive mark for the wounded. Given the date of this letter, it is feasible that his letter served as the inspiration for adopting wound stripes. The failure to create medals for these other events implies that they paled in comparison to the Great Patriotic War that was then being waged.145 Veterans were invested in making sure that their service was not forgotten, and many seemed to understand the language of hierarchy and distinction that medals offered, trying to shape its development.

Not everyone was enamored with the enameled language of power and recognition. Rashid Rafikov wrote home in 1944 after receiving an Order of the Red Star: “Of course, to get an order is a not a bad thing, if you survive this and keep your head on your shoulders. Otherwise I have no interest.”146 Even Tvardovskii’s Vasilii Tërkin preferred going home to a medal.147 The war correspondent Aleksandr Lesin talked to a man who, having been wounded, smoked the paper his recommendation was written on: “‘I smoked up my order’… Try to interpret this fact. Wouldn’t it be better to say that it not in order to get decorations that we fight the fascists!”148

Beyond these examples, it was not unheard of for soldiers to receive decorations for reasons other than combat service. One agitator received the For Valor medal for organizing a talent show, and many frontline veterans were infuriated that rear-echelon troops received medals while the services of those risking their lives often went undistinguished.149 In the Second Guards Paratrooper Division, some officers wrote themselves up for fictitious feats of bravery and denied heroes decorations, while others promised medals to men and women for certain services, such as “sewing boots, giving out new costumes, for giving fuel, for living together [sozhitel’stvo].”150 The final category was particularly painful for women in the ranks, as it cast a shadow on all of them. Iakov Aizenshtat recalled of 1943: “Medals and orders were quite a rarity then, even among those who had been at the front from the first day. I looked at the secretaries of the Front Tribunal, young women, and on their chests were orders and medals. It was clear to all, what they had received these medals for.”151 Soldiers’ relationships with their commanders, who wrote recommendations for medals, were key to whether a soldier received decorations. In some situations, medals and orders became—or were perceived as—a sort of ersatz jewelry for officers’ lovers, while women who refused officers’ advances could be overlooked for decorations, regardless of their accomplishments.

Once recommendations were written, another set of factors came into play. Irina Dunaevskaia recalled that medals were usually conferred only when the army was advancing, as celebrating acts of heroism during a retreat brought attention to defeats. In general soldiers usually received a decoration a “step” or two lower in the official hierarchy of awards than they were recommended for.152 Sometimes it was impossible to determine the names of those who should be awarded, as they spent so little time in the unit.153

Despite the often petty politics of medals, decorations gave the bearers a form of legitimacy as defenders of the Motherland that continues to resonate. Decorations were tied to concrete actions or moments in the bearers’ lives and as such were an object pinned directly into their biography and put on public display. Medals were publicized and recognizable by soldiers and civilians. Soldiers could tell their stories via wound stripes and their decorations, lending a biographical element to the soldier’s uniform, personalizing an otherwise anonymous article of clothing. For example, just by looking at the portrait of Guards Senior Sergeant Bato Damcheev (figure 2.4), we can tell that he is a Guardsman, was wounded twice, served as a scout and sniper, and fought at Stalingrad. We can also get a sense of the deeds he had to perform to earn two Combat Service medals and an Order of Glory.154

Nonetheless, this remained a language of power that the government controlled. The hierarchy of awards and the regulations on how they could be worn provided a sort of grammar of this language, but its real meaning was always subject to the state’s control. Once medals started becoming more prevalent, concerns that soldiers might rest on their laurels mounted. One war correspondent for Pravda wrote from the Steppe Front in November 1943: “The generous awarding of decorations has gone to many people’s heads… Brave soldiers need to be given orders, while those who have shamed themselves, who put on airs, need to have their orders taken away.”155 In July 1944, Shcherbakov warned that on the Second Ukrainian Front: “people live in the past, live yesterday’s victories.”156 After the war this logic took on a menacing dimension. On January 1, 1948, all benefits tied to decorations were cut. While this had a significant financial component, as the value of benefits to veterans reached over 3.4 billion rubles by 1947, many veterans saw the loss of benefits as a betrayal.157 Veteran Grigorii Pomerants recalled his reaction: “all of us with our orders, medals, and wound stripes became nothing.”158 Nonetheless, during the war, and, later, during the revival of the war as a foundational myth under Brezhnev, medals continued to be a point of pride, embodying the story of one’s life at the front.159

Outerwear

Soldiers’ overcoats (shineli) were single-breasted, sewn from coarse wool with hook and eye closures, while commanders had more ostentatious double-breasted models with buttons. Like the tunic, the overcoat bore rank and branch of service insignia, large diamond-shaped collar tabs in bright colors and chevrons, then muted defense collar tabs, and finally pogony with new model collar tabs, rectangular and showing reintroduced branch of service colors, from 1943 on. The basic outline of the overcoat had not changed since the time of the war with Napoleon.160 In 1945 Aleksandr Lesin overheard a German woman say, that “all the Russians have left their land and put on overcoats; this is our punishment.”161 The overcoat was one of the iconic symbols of the Red Army soldier, engraved on the Order of the Red Star and prewar sculptures. The phrases “to put on the overcoat” and “in overcoats” are ubiquitous allusions to military service.162

Despite their symbolic power, overcoats were heavy and often among the items soldiers discarded, and one quartermaster suggested that they be withdrawn during summer.163 Such losses would generally be temporary at the front, as one could usually receive secondhand outerwear from the dead.164 Red Army soldiers were not issued blankets, instead overcoats were carefully folded and tightly wrapped into a blanket roll, which could provide a psychological sense of protection.165 When improperly rolled, the rough wool of the overcoat would rub soldiers’ faces raw and impede their movement.166 Like most of the rest of a soldier’s kit, the overcoat required practice and special knowhow to be used in a way that would not cause suffering.

Soldiers in the Red Army gave their overcoats mixed reviews. A veteran of the Finnish campaign remembered that the gray overcoats provided no concealment and hampered movement: “in the snow, we were like flies in sour cream.”167 Later the army shifted to a dark brown dye that blended with the earth. Many soldiers shortened the bottom of the overcoat to improve movement. As with all other items, size was key. Lesin recalled in 1942: “we were issued uniforms, overcoats. I got a shorty. It barely covers my knees, and the back belt is practically at my armpits. I won’t be going to have my picture taken.”168 Genatulin rated the overcoat the ideal garment for soldiers: “Not very pretty, not always the right size, for soldiers it served as featherbed, mattress, and blanket on the bare ground, in the trench, and even in the snow.”169 Soldiers curled up together under overcoats: “There is no brotherhood that binds people closer than the brotherhood that is shared in the lines, and a shared greatcoat is one of its symbols. You feel warm and secure with a friend close by.” Soldiers used their knapsacks or mittens as pillows, their rain-cape/half-tents as mattresses, the “shabbier” of the two overcoats to cover their feet, and the better of the two to cover their heads in a sort of “sleeping bag, warm and cozy.”170 Those in service became bedfellows via the overcoat, as the cold and the military’s practicality and frugality forced people into greater intimacy. The overcoat could be improvised into a stretcher and its hems became a wick for improvised lanterns.171

The overcoat was one of several items issued for winter wear. A padded cotton jacket called a vatnik, fufaika, or telogreika (body warmer) was a traditional cold-weather garment initially considered an undergarment by the army, but it had become outerwear during the Winter War. (See figure 1.4.) It was considered to be less desirable than the overcoat, authorized for rear-area personnel to provide enough overcoats at the front and regarded as not dignified enough for soldiers to appear in public wearing them from 1943 on. More stylish were polushubki, lambskin coats initially authorized for officers only, but which more and more soldiers wore as the conflict continued.

Red Army personnel suffered from frostbite and the elements as much as any humans, and supplying sufficient cold-weather wear was a constant concern. The situation improved as the war continued.172 The gov ernment and soldiers worked to define themselves in contradistinction to their enemies, who were portrayed as constantly suffering at the hands of “General Winter.” “Winter Fritzes” were stock characters of propaganda, appearing in documentary films, cartoons, and the soldiers’ own drawings. Consistently shown wrapped in women’s shawls and bast shoes that gave them a pathetic, unmartial, and feminine appearance, they emphasized that winter was the period of the Red Army’s initial victories and the humiliation of the enemy.173 Pathetic groups of these beggar-like figures were often seen being led by a single Red Army man, proud and erect in his overcoat.

Belts

In order to stand proud and erect, the soldier needed a belt that would draw in the waist of the loose-fitting overcoat (which had buttons placed as a marker for the belt) or tunic.174 Belts served many of the same functions that a tie serves in the professional world, as a soldier was not in uniform without one.175 The belt was one of the first things taken from a soldier under arrest.176 Soldiers were instructed in how to make tourniquets using their belts and how to properly wear them so that their equipment didn’t flop and in regulation alignment. In full kit a soldier carried cartridge boxes, grenade pouches, a spade, a water bottle, and sometimes a bread bag on their belt.177 Belts were important as both functional and decorative items, and as with everything else, a hierarchy of belts existed in the army. Before the massive expansion of the army in the late 1930s, all soldiers’ belts were thin leather with roller buckles, with officers having a variety of wide, high-quality belts decorated with ostentatious buckles of the Sam Brown variety or a hammer and sickle. With the expansion of the army, and particularly once the war began, most soldiers’ belts were thick cloth of various colors with rough leather binding (see figure 1.3). Leather belts became premium items, borrowed for special occasions such as dates, stolen from comrades, or used to mark a privileged position.178 Generals, a rare sight, surprised some soldiers by the fact that they did not wear belts, having finely tailored clothing.179

Headgear

Headgear changed with the seasons, and like belts it acted as a clear indicator of hierarchy. The earliest hats of the Red Army had been peaked caps and the budёnovka, or officially shlem, most popularly known for General Semën Budënnyi, famed cavalry commander of the Civil War. Having a large enameled red star and a large cloth star in branch of service color, the budёnovka looked like something from another era. One version gives authorship to the artist Boris Kustodiev, another to the imperial regime.180 According to Isaak Mints, the preeminent Soviet historian during the war, the Bolsheviks consciously chose headgear that resembled the legendary knights of ancient Rus’.181 The outline of the shlem recalled ancient Russian warriors and onion-domed churches, many of which would be destroyed by men wearing these hats during the First Five-Year Plan. This most distinctive uniform item of the Red Army, coming in both summer and winter weights, was officially discarded in 1940, as it was found to be too cold, but continued to be worn through 1942 and could still be seen on surviving POWs in 1945.

The budёnovka was replaced by the shapka-ushanka, a militarized version of a traditional winter hat. The standard issue ushanka was made of cotton, sometimes called “fish-fur,” and although it was quite warm, some soldiers found it to be particularly ugly. (See image 4.14.)182 For many soldiers, their hats became talismans, a long-lasting item that became molded to the wearer’s head.183 Headgear was said to retain the distinctive smell of its wearer—usually a mix of sweat, hair, and soap. Hats were also the place where soldiers tended to store a needle or two with thread to make repairs to their clothing.184 Some claim that soldiers in hospitals could not sleep without their hats, as soldiers did everything—even faced death—wearing their hats.185 Despite attachment, as winter turned to spring, budёnevki and ushanki were replaced by pilotki (wedge caps), furazhki (forage caps), and sometimes berets for female soldiers. Every change of headgear was a marker that one had survived another season.186 The pilotka was similar to headgear worn by most armies at the time, as were forage caps. All headgear carried a star with hammer and sickle that was at first red enamel and later changed to defense green, like collar tabs and rank pips. Officers wore a finer-quality pilotka with edging in branch of service color or forage caps with a bright band of material in their branch of service color until the turnover to olive drab (though the earlier caps remained popular). (See figure 6.1.) Generals had distinctive headgear: in winter the papakha, which recalled revolutionary heroes such as Chapaev; and in summer forage caps with ostentatious insignia.187

In elite formations—such as armor troops, cavalry, border guards, and NKVD units—personnel were authorized to wear forage caps, and sailors either black pilotki or sailor’s caps with their ship’s or fleet’s title. As the war continued, many cavalry and scout units came to wear fur kubanka caps year round.188 These flourishes contributed to a distinct corporate identity that made its members stand out in an otherwise anonymous mass institution and many of these symbols still evoke strong associations.

By regulations, ushanki and peaked caps were worn straight, and pilotki at a slight angle, two fingers above the eyebrow, with the star over the center of the face.189 However, as Alexandra Orme observed, soldiers wore their caps every which way and their angle could speak volumes: “For you must know that a Russian soldier’s cap is far from being just a covering for his head. If I had to deal with a dumb Russian soldier, I could guess his innermost feelings simply from the movements of his cap. The cap serves to express those feelings for which there are no words in imperfect human speech. The Red Army cap, as we came to realize has a language of its own.”190 Orme proceeds to describe how every emotion has its own angle, particularly once soldiers start drinking. Photographic evidence shows soldiers wearing their caps at a variety of angles, yet another example of the tiny ways in which soldiers made their mass-produced, standard-issue uniforms their own.

Uniformity and Individuality

Red Army uniforms were humble and required special knowledge to be worn properly—the proper fold of portianki, a tunic, or an overcoat was the difference not only between looking sharp or like an unmade bed but also between being comfortable or blistered and bloody. Soldiers learned how to wear and feel at home in these garments, which reflected both the shoestring budget of the Red Army and the peasant origins of its cadres. The Soviet Union skimped on uniforms and gear but not on weapons and medals. Many soldiers who donned the uniform earned distinction, transforming the anonymous cloth the army issued them into a personal banner showcasing their exploits on the battlefield. These exploits were translated into medals and orders devised by the Soviet leadership that spoke an official language dictated by the government.

Millions of people from different backgrounds passed through the ranks of the Red Army. When people stood in ranks, with tunics buttoned tight, boots shined and belt properly centered, it was not necessarily clear who was a peasant, a student, a worker, or a former criminal. Underwear would circulate among all of them. A Ukrainian would share his overcoat with an Uzbek, a convict and a Komsomol member could receive the same medals, and “backward” peasants would command “conscious” students.191 Donning the uniform, men and women were exposed to a peculiar military modernity that forced them first to master proper wear and etiquette, and then the art of killing, relying on each other for survival. Officially, they would no longer be distinguished by their class, age, ethnicity, or education but rather by their rank, specialization, and the decorations they had earned via personal achievement on the battlefield.

Yet the army could never completely transfigure all of the men and women who filled its ranks. The juxtaposition of yesterday’s peasants and ultramodern technology sometimes created visual dissonance: “In surprising contrast to the armored column appeared a little mule, quietly grazing by the side of the road. An old Uzbek in a pilotka, stretched like a tiubeteika [skull cap] on his head, with a rifle over his shoulder, rode astride, half asleep, along the ditch.”192

The process of becoming a Red Army soldier consisted of both adjusting to uniforms and making them personal. Even as the army effaced many aspects of earlier identities, there were still times and places when one’s prewar biography and habits bled through khaki tunics and gray overcoats. Every soldier wore the cap a little differently, despite regulations. Everyone knew which pair of boots, which belt and which tunic were theirs, despite the fact that all these items were standard issue. Soldiers found ways to individualize their humble belongings, using both the government’s language of distinction and their own simple means—whether through tailoring or simply wearing something in their own particular way. They left their mark on boots, hats, and tunics that all wore out in ways specific to their wearer’s body and came to have their particular smell. Many of them also earned decorations that told of their exploits in the Soviet idiom of enamel and metal. However, doling out medals was not the only way the government showed its appreciation for soldiers. A much more humble, but vital measure was also used to mark their worth—the calorie.