Chapter 7

Where’s Waldo?: Public Information Searches for Law Librarians

Remember the movie The Net? Sandra Bullock plays the role of Angela Bennet, a software analyst who stumbles upon a floppy disk belonging to the Praetorians, a gang of cyberterrorists. One of the terrorists, Jack Devlin, played with creepy élan by Jeremy Northam, tries to romance the disk out of Angela. When that doesn’t work, he erases her. Cancels her credit cards. Crashes her best friend’s plane. Sells her house. Gives her a new name and passport plus a criminal record, which leads to her arrest. Sitting in jail, she babbles to her court-appointed attorney, “Our whole world is sitting there on a computer … your DMV records, your Social Security [number], your credit cards, your medical history. It’s all right there; everyone is stored in there. It’s like this little electronic shadow on each and every one of us just begging for somebody to screw with.”

Here’s the weird thing about The Net: It was science fiction. The movie was made in 1995, when cybercrime was as far-fetched as Klingons and Romulans. Watching it now, we laugh at the primitive websites that Angela visits and the bottle-sized cell phone that Devlin holds to his ear. But we don’t laugh at the “little electronic shadow.” Identity theft is the new shoplifting. The Federal Trade Commission estimates that as many as 9 million Americans have their identity stolen every year.1

As a law librarian, I have often used the internet to locate public information, though not for nefarious reasons. There are plenty of bona fide reasons to pursue that electronic shadow. Courts need to find people to serve subpoenas. Managers have to do background checks on job applicants. Banks want credit reports before lending money. I have also been asked to find information on specific companies or their executives, usually to assist my law firm’s marketing or business development efforts (see Chapter 8).

Public Information

Types of public information include:

- Birth and death certificates

- Marriage licenses

- Asset sales (e.g., cars, boats, airplanes, stocks)

- Internet directories

- Voter registrations

- Political contributions

- Civil and criminal filings

- Liens, judgments, and UCC filings2

- Real estate sales

- Property records

- Professional licenses (e.g., lawyer, doctor, architect, plumber, mortician, cosmetologist)

- Corporation filings

- Motor vehicle records

- Foundation and charity donor records

- Social media sites (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn)

The following books and websites are great tools to begin a search for public information.

Helpful books include:

- Levitt, Carole A. and Mark E. Rosch. Find Info Like a Pro, Volume 1: Mining the Internet’s Publicly Available Resources for Investigative Research. Chicago: American Bar Association, 2010.

- Levitt, Carole A. and Mark E. Rosch. Find Info Like a Pro, Volume 2: Mining the Internet’s Public Records for Investigative Research. Chicago: American Bar Association, 2012.

- Sankey, Michael and Peter Weber. The Sourcebook to Public Record Information: The Comprehensive Guide to County, State, & Federal Public Records Sources, 10th ed. Tempe, AZ: BRB Publications, 2009.

Useful websites are:

- BRB Publications (www.brbpub.com): Several free sources plus books and electronic products pointing the way to over 26,000 government agencies and 3,500 public records vendors

- Business Intelligence Online Resources (www.llrx.com/features/busintellguide.htm): Dozens of sites useful for business and company research

- Finding People Online (www.libraryspot.com/features/peoplefeature.htm): Guide to tracking down those who have tried to disappear

- Gumshoe Librarian (www.llrx.com/features/gumshoe.htm): Bibliography of websites useful for locating people

- How to Find People on the Web (websearch.about.com/od/peoplesearch/tp/peoplesearch.htm): Another guide to finding people

- SearchSystems.net (www.searchsystems.net): Over 38,000 databases containing business information, corporate filings, property records, deeds, mortgages, criminal and civil court filings, records on inmates and offenders, births, deaths, and marriages, unclaimed property records, professional licenses, and more (subscriptions cost less than $50 per year, making this one of the least expensive in the industry)

- State and Local Government on the Net (www.statelocalgov.net): Over 8,000 official state, county, or city government websites

- Virtual Chase (www.virtualchase.com): Articles on public records, locating corporate information, and finding people

- Virtual Gumshoe (www.virtualgumshoe.com): Maintained by a pair of private investigators, over 4,000 public information databases (most of the site is free, although there are services—e.g., a 24-hour criminal record check—that require payment)

Company Information

The old saw of law librarianship is that the litigators keep the library in business. Litigation, civil or criminal, is when attorneys are researching cases and statutes, studying concepts, and developing theories. Transactional attorneys, those handling mergers, acquisitions, restructurings, and other business deals, rarely darken the door of the library—except when they need information on a particular company.

The obvious place to start such research is a company’s website, where you can learn a lot. I was once asked to discern the relationship between two companies: Nan Ya Technology and Formosa Plastics Group. On the website of Formosa Plastics Group, I found a diagram of its corporate structure. The diagram named Nan Ya Technology Corp. and Nan Ya Plastics Corp. as “local companies” with a hard-line direct report to the president of Formosa Plastics. This suggested that both Nan Ya companies were owned by Formosa Plastics.

Other requests aren’t so straightforward. For a company overview, you need a strategy. I recommend the following five steps:

- Look for information on the company executives.

- Locate the company’s financial information (e.g., SEC filings, current and historical stock prices, analyst reports).3

- Check news databases for mentions of the company.

- Examine the company’s interest or involvement in legislative or regulatory actions.

- Find out the public opinion of the company.

There are several commercial databases useful for company (and personal) research and background investigations:

- Accurint (www.accurint.com): Owned by Lexis; offers access to over 34 billion public records

- CLEAR (www.clear.thomsonreuters.com): Originally known as ChoicePoint (a term you might still hear); acquired in 2008 by Thomson West; maintains records on businesses and individuals; benefits from the top-of-the-line West search engine technology

- Dun & Bradstreet (www.dnb.com): In business since 1841, the oldest company of this type; maintains records on over 200 million companies worldwide

- Hoover’s (www.hoovers.com): A subsidiary of Dun & Bradstreet; maintains records on over 60 million companies (also has records on individuals); has less-detailed records free of charge on its website

In a midsize firm or public library, however, you will probably not have access to these. The following are some good free websites.4

For finding company executives:

- CPA Directory (www.cpadirectory.com): Contains the names and addresses of 450,000 certified public accountants in the U.S.; from the homepage, searchable by name and state (city is optional)

- Executive Paywatch (www.aflcio.org/corporate-watch/CEO-Pay-and-the-99/CEO-Pay-Data-Sources): An executive compensation database; searchable by company name or ticker symbol, or look at the list of 100 highest-paid executives

- Ziggs (www.ziggs.com): More than 1 million executive profiles from 15,000 companies and 40 industries; searchable by last or first name, city/state, company, or keyword

For finding financial filings:

- 10K Wizard (www.10kwizard.com): SEC filings made since 1994; a useful feature includes searching for model language that appears in all types of filings5

- Big Charts (www.bigcharts.com): Historical single-day stock quotes back to 1988; also offers comparative NYSE, NASDAQ, and AMEX reports; advanced tools available to paid subscribers

- EDGAR (www.sec.gov/edgar.shtml): Official database of SEC filings; includes only searchable data found in the header of the document

- Investing in Bonds (www.investinginbonds.com): Historical trading data for municipal bonds, as well as daily corporate bond transactions and composite treasury reports

- Yahoo! Finance (finance.yahoo.com): One-stop shop for company and market information; links to historical stock prices (some back to 1960s), analyst reports, financials, and news

For finding news stories:

- American City Business Journals (www.bizjournals.com): News by industry, region, or keyword; email news alerts available

- Bloomberg.com (www.bloomberg.com): Mix of free and fee-based news stories on markets, economies, and companies around the world; special feature provides current stock information, found by entering a ticker symbol

- Corporate Crime Reporter (www.corporatecrimereporter.com): Subscription newsletter reporting on lawsuits, agency actions, and other events; lists the top 100 corporations charged with crimes, hot documents (e.g., Martha Stewart’s 2004 indictment for lying to federal investigators), interviews with white-collar crime defense lawyers, and more

- I Want Media (www.iwantmedia.com): Directory of news sources and organizations; also links to about a dozen good research sites

- Television News Archive (www.tvnews.vanderbilt.edu): Abstracts of evening news stories and special reports back to 1968

- U.S. Newspaper List (www.usnpl.com): Websites of newspapers, radio stations, and TV stations in all 50 states; also lists sites for stock quotes, maps, weather, and more

For finding information on legal or regulatory activity:

- Analysis and Information Online (ai.volpe.dot.gov/mcspa.asp): Single point of entry to transportation-related databases, where you can find extensive statistics (e.g., 14 percent of those killed in large truck crashes in 1999 were the truck’s occupants)

- Congressional Record (thomas.loc.gov): Transcripts of debates on the floor of Congress (Congressmen often read a company’s written remarks into the record); also available through ProQuest Congressional database (see Chapter 6)

- Corporate Registration, The National Association of Secretaries of State (www.nass.org/busreg/corpreg.html): State sites with information about registering for-profit and nonprofit corporations

- FreeERISA.com (www.freeerisa.com): Free reference databases of companies’ Form 5500 filings, Form 5310 filings, pension funds, and SEC filings; also has a library of National Labor Relations Board decisions, collective bargaining agreements, and more

- MedWATCH (www.fda.gov/safety/MedWatch/default.htm): Clinical information about safety issues involving drugs, biologics, radiation-emitting devices, and nutritional products; browsable by safety alerts or company name

- NLRB Decisions (nlrb.gov/cases-decisions): National Labor Relations Board decisions from 1996 to present

- SEC Enforcement Division (www.sec.gov/divisions/enforce.shtml): Litigation releases, administrative proceedings, notices about trading suspensions, investor alerts, and more

- WebBRD (lopucki.law.ucla.edu): Database of public company bankruptcies beginning in 1980

For finding information on public opinion:

- BBB Reviews (www.bbb.org/us/Find-Business-Reviews): Database of business and clarity reviews by the Better Business Bureau

- CorpWatch (www.corpwatch.org): Reports on corporate activities worldwide; tips and strategies for finding information about companies, public or private

- Google Groups (groups.google.com): Newsgroup messages since 1981; searching for company or executive names to see what people have been saying

- ResellerRatings.com (www.resellerratings.com): Consumer opinions about online vendors for computer hardware or software; the vendors are rated accordingly

- Yahoo! Consumer Opinion (www.snipurl.com/d8ys): Websites devoted to public opinion

Individual Persons

Searching for information on an individual person may seem overwhelming, so plan your search before you sit down at the computer. Here are some tips to keep in mind:

- Know what you need. Most searches are simple: an address, phone number, or date of birth. You can find this free on the internet.

- Consider a low-tech approach. Call friends, relatives, clubs, churches, or former employers of the person you’re looking for. If you have an old address, send an envelope marked “Address Correction Requested/Do Not Forward.” The post office will label the envelope with the current address and return it to you.

- Understand that some information, such as credit histories, Social Security numbers, and motor vehicle records, is never free.

- Don’t trust pay databases implicitly. All databases have errors, so verify (if you can) what you find in them. In 2005, for example, the public records vendor ChoicePoint6 made headlines for having legions of errors in its database. One woman’s profile showed cars she had never owned and employers for which she had never worked. Another man read his profile and learned that he died in 1976.

To Strive, to Seek, to Find

Have you ever Googled yourself? I do it every few months. Usually, I find articles I’ve written or the website of the university where I teach. However, I’ve also found the car salesman in Mt. Gilead, Ohio, who shares my name. Once, I found my grandmother’s newspaper obituary, which I had not yet seen.

When you’re searching for a person, it’s tempting to start with Google, but I don’t recommend this. Besides Arnold Schwarzenegger, few people have a name so uncommon that Google will suss them out. Better to start with White Pages (www.whitepages.com) or a similar site, all of which work by searching telephone directory listings. The drawback to this is obvious: People who skip bail, break their lease, or fail to pay loans probably also don’t publish their addresses and phone numbers. However, when you need to find regular people, White Pages can give you a lead.

Suppose I want to find my ex-girlfriend, Jamie Hunter, so I can return her stuff that I recently found in my closet. When I last saw Jamie, her company was about to transfer her to Baton Rouge, Louisiana. I go to AnyWho (www.anywho.com), type her name, choose LA from the drop-down box, and—bingo! Only one Jamie Hunter comes up.

But what if my Jamie has moved? What if she has an unlisted phone number? What if she is married and has a different last name? What if she married, changed her last name, divorced, and changed her name back? How do I know whether this Jamie Hunter is the one I want?

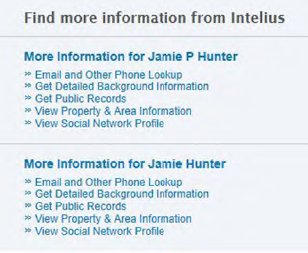

To the right of the screen, I see a list of reports I can buy (see Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Reports available to buy after a person search

The reports range from $1.95 for an email address to $49.95 for a complete background check. Would I consider buying one of these reports? If I wanted to find her badly enough, sure. If I choose to buy a report, however, I need to buy several from different vendors. Why? Remember the ChoicePoint problem: Vendor databases have errors. Looking at one report, I don’t know what is accurate, but if I look at several and see the same information in each one, that information is likely correct.

Similarly, I always keep a log of my searches, noting every person I talk to and every website I visit. Then I compare each new search result to what I’ve written in my log and look for consistencies as well as contradictions. There are thousands of websites I could have started with, many of which are mentioned in the tools at the beginning of this chapter. The key to finding people, however, is not which site you use; it is how you analyze the findings.

Another key: Be creative. I knew a woman who was trying to locate her ex-husband because he was behind on child support payments. She checked his voter registration and that of the woman he had left her for—all states make voter databases available online—and she noticed that both had changed to the same voting district. This implied the two had moved in together. Thinking they might be engaged, my friend checked with department stores in that area and located their bridal registry, which gave her their address and phone number.

Finding Waldo

Suppose you are the librarian for a firm defending a physician accused of medical malpractice. In treating a patient who had a temporary pacemaker, the physician failed to provide anticoagulant therapy, and the patient died from a stroke. You find a case where the same thing happened, and the case mentions a Dr. Albert Waldo who served as an expert witness. Your firm wants Dr. Waldo for its witness, but first you need to locate him, check his credentials, and find out what he’s done the last few years.

Again, you could pay for this at many site, such as Healthgrades (www.physicianreports.com), MDNationwide (www.mdnationwide.org), and DocInfo (www.docinfo.org). If you are unable or unwilling to pay, however, you can find a lot of information free online by conducting a “Where’s Waldo?” search.

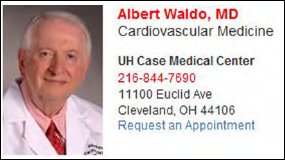

Despite my earlier importuning, you should start this search with Google. Why? Because you want to know Dr. Waldo professionally, not personally, and if he has a website, your search is half over. You run the search and come up with Dr. Waldo’s address and phone number at the UH Case Medical Center (see Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 Listing for Dr. Albert Waldo

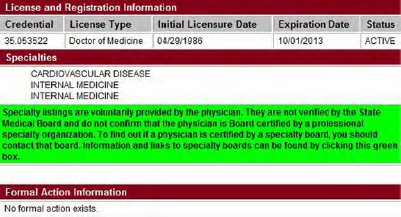

This contact information, however, isn’t enough. Before calling the good doctor, your firm will want to check his reputation and his expertise. After all, the reason some doctors turn to the expert witness gig is because their credentials have been stripped. Better visit the State of Ohio Medical Board at www.med.ohio.gov and run a search. You find Dr. Waldo’s name, address, and education, followed by the most important info: No formal action on his record. This means he has been found guilty of no professional malpractice. In other words, he isn’t a quack (see Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 Dr. Waldo’s license information

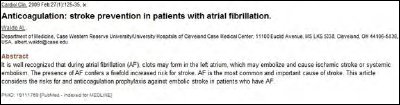

There is one more piece of information your attorneys will want: articles written by Dr. Waldo. I mean the dry-as-dust ones published in the medical journals no one reads. For that, go to www.pubmed.gov. Search for Dr. Waldo as the first author. Most medical articles are co-written, with the first author on the list having done the bulk of the research, making him or her the most knowledgeable about the study results. Figure 7.4 shows one of Dr. Waldo’s articles as listed on PubMed.

Figure 7.4 PubMed entry for one of Dr. Waldo’s articles

The article is not available in full text, so you will need to get this one via interlibrary loan.

Laws Governing Personal Information

Trying to find an old girlfriend or getting the lowdown on a physician seem like harmless, maybe even necessary, exercises of power, and they are, if you search only public sources of information such as newspapers, phone directories, or court filings. Commercial databases like those mentioned earlier, however, are off-limits unless you are a licensed professional or you have a legal interest in the search.

The following statutes regulate who may research a person’s financial information and what that researcher may do with the results:

- Fair Credit Reporting Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1681 et seq.

- Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1692-1692p

- Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 6801-6809

You could also use a private investigator. PIs are regulated by most states. In North Carolina, for example, N.C.G.S. Chapter 74C is the Private Protective Services Act. The regulations implementing this Act can be found in 12 N.C.A.C. 7D. PI Magazine links to the private investigator laws for all 50 states.7

Courthouse Filings

Attorneys frequently ask for copies of filings—motions, complaints, answers, appellate briefs, and more—in actual court cases. One reason is these documents will list a person’s name, address, occupation, place of employment, financial holdings, marital status, bankruptcies, and other useful information. With cases involving companies, you can find out about the officers and directors, the company’s financial holdings, and more.

Another reason to obtain copies of filings is to use them as models for the attorney’s own documents. West and Lexis publish books of forms for this purpose (see Chapter 2), but in my experience, attorneys always prefer a live document. Why? It has specific language and arguments they can adopt. Is this plagiarism? No. Court filings are public records, unprotected by copyright.

Westlaw and LexisNexis include many court filings, federal and state, in full text. These databases are among the most expensive, however, so small firms and public libraries tend not to have them. A cheaper source for U.S. appellate, district, and bankruptcy filings is Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER; www.pacer.gov), a service of the U.S. courts, which has over 500 million documents. Any member of the public can access PACER at a cost of 10 cents per page. Bills are sent quarterly, and if your access charges don’t amount to $15.00 that quarter, then you pay nothing.

The states, as you might expect, have differing levels of access to civil and criminal filings. The National Center for State Courts has an excellent guide on this topic.8 Older records are not available electronically, and no courthouse staff will find, copy, and send you documents. For these records, you will need to hire a runner, someone who will go to the courthouse and copy the documents for you. West has such a service (www.courtexpress.westlaw.com), as does Lexis (www.lexisnexis.com/courtlink). Both operate nationwide. Other, smaller companies limit themselves to one state (e.g., www.courthouserunners.com in South Florida) or one type of record (e.g., www.courthousedirect.com, specializing in property and bankruptcy records).

Appellate Briefs

Attorneys writing an appellate brief frequently want to study other briefs on the same topic. U.S. Supreme Court briefs are the easiest to find. Westlaw and LexisNexis have many, and some are available free online. Other federal briefs can be retrieved using PACER.

For state-level appellate briefs, start with state court websites, all of which are listed by the National Center for State Courts.9 Another great source is the article “Free and Fee Based Appellate Court Briefs Online” by Michael Whiteman on LLRX (www.llrx.com/features/briefsonline.htm), listing free and commercial sources, as well as merits and amicus10 briefs by various government agencies and nonprofit associations.

Endnotes

1. “Identity Theft,” Crime Museum, accessed February 24, 2013, www.crimemuseum.org/Identity_Theft.html.

2. UCC stands for Uniform Commercial Code, a set of suggested laws relating to commercial transactions. The code was developed by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, an independent group. Most states have adopted the code, though none are required to do so.

3. This is much easier for public companies (i.e., those traded on a stock exchange). Private companies are more elusive.

4. Website descriptions are adapted from resources available at www.virtualchase.justia.com.

5. Attorneys will often ask you for actual filings, contracts, or other documents to help them draft their own.

6. Now owned by Lexis. See https://personalreports.lexisnexis.com.

7. See the state license requirements at www.pimagazine.com/private_investigator_license_requirements.html.

8. Links to state court filings databases, free and commercial, are available at www.ncsc.org/Topics/Access-and-Fairness/Privacy-Public-Access-to-Court-Records/State-Links.aspx.

9. All state court websites are available at www.ncsc.org/Information-and-Resources/Browse-by-State/State-Court-Websites.aspx.

10. Amicus means “friend of the court.” Amicus briefs are filed not by the participants in a case but by interested trade groups or nonprofit associations who want the court to consider their interests. Usually, the court does not.