Reimagining Communism after 1968: The Case of Grapus

In early 2013, to little fanfare, the French Communist Party (PCF) decided to drop the hammer and sickle from its membership cards and official imagery and replace it with a star whose five points represent the parties of the Left Front coalition to which the PCF has belonged since 2009. Within the party there was some grumbling from traditionalists but, as national secretary Pierre Laurent explained, “We want to turn towards the future … [The hammer and sickle] doesn’t represent the reality of who we are today. It isn’t so relevant to a new generation of communists.”1 Though the hammer and sickle had been the official insignia of the party since its establishment in 1920, by 2013 the notion that logo rebranding might update the PCF’s image among the French populace seemed naïve at best. Membership and electoral fortunes had been in steady decline since the founding of the Fifth Republic in 1958. In the general election of 2012, the Left Front managed 6.9 percent of the national vote—far behind the extreme right-wing National Front.

What seemed to be at issue with the logo change was an attempt by the party to shed certain associations that inhibited its appeal for younger workers and partisans. Certain of those compromised associations were explicit. The industrial and agricultural labor iconographically denoted had long ago ceased to comprise the majority of waged labor in France.2 There was also, of course, the outmodedness of the symbol’s connection to the Soviet Union and twentieth-century geopolitics. However, the decision to abandon such a venerable component of the party’s visual identity evinced an ambivalence about the role of the party within contemporary France that had characterized the PCF throughout the history of the Fifth Republic. It was also not the first time that graphic design had attempted to address that ambivalence and respond to the changing of cultural winds.

This was the task undertaken by Grapus, a collective of communist graphic designers born from the maelstrom of 1968 who, over the course of the 1970s, attempted to update the image of the PCF and its affiliated labor union, the Confédération générale du travail (General Confederation of Labor, CGT) by harnessing the spirit of youthful revolt that had emerged from 1968 and which was in marked contrast to the organizational structure and ideological orientation of these venerable institutions. The contradictions of this pursuit would mark the group’s interactions with the PCF and CGT as well as the images they created, thereby producing some of the most historically rich visual responses to the events of May 1968.3 Typically overshadowed in the historiography on French leftist visual culture of the 1960s and 1970s by, on the one hand, the posters and graffiti produced during the May events, and on the other, by experimental practices such as those of artists associated with groups like BMPT,4 the Situationist International,5 or Supports/Surfaces,6 Grapus offers a more sustained focus on how images struggled to cope with the changes the left confronted and underwent during this period.

By the mid-1980s, however, the contradictions could no longer be sustained and Grapus’s engagement with the PCF and CGT came to an end. The few considerations of this endeavor that exist stress the inflexibility of PCF structure and dogma, contrasting the strictly political goals of the party with the creative artistic liberty of Grapus.7 I will argue, however, that the designs Grapus developed for the Communist Party and labor union as well as their eventual foundering stemmed from the incompatibility of a fragmenting French left to representation in the wake of 1968. That is, May 1968 posed a direct challenge to the authority of signs, institutions, and organizations to refer to or speak for shifting material conditions and subjectivities. Rather than rehearsing the conflict between reductive binaries of art/politics, autonomy/subordination, or creativity/dogma, the case of Grapus should be seen as one of images attempting to negotiate the centrifugal forces of the post-1968 period.

Grapus was founded in 1970 by three graphic designers and PCF members: Pierre Bernard, François Miehe, and Gérard Paris-Clavel. Bernard and Paris-Clavel had previously spent time in Warsaw, studying poster design with Henryk Tomaszewski, pioneer of the Polish Poster School style.8 All three had played a central role in the silkscreen poster workshop established in the occupied École des Arts-Décoratifs during May and June 1968. The central mission of Grapus was to develop a role for graphic design in the public sphere in support of left-wing causes. By 1976 Alex Jordan and Jean-Paul Bachollet had joined the core group as younger designers moved into and out of the studio. Miehe left Grapus in 1978 and the group began to take on more commissions from cultural institutions. Struggling to support itself financially, Grapus officially disbanded in 1990 when an invitation to participate in the design of the Louvre’s new graphic identity split the group.9

The question of political representation had already surfaced before the outbreak of French student and worker uprisings in May–June 1968. Prior to 1968 the PCF was France’s largest left-wing political party while the CGT, as France’s largest and oldest labor union, could credibly claim to represent the economic interests of the working class.10 This, however, did not cover the exponentially growing student population of the postwar period or the ranks of the expanding white-collar workforce they were being trained to enter.11 This was a cohort that didn’t necessarily identify with the PCF’s workerist rhetoric and, even when expressing leftist orientations, was in turn viewed with suspicion by the party. Politicized university students were often more apt to support anti-imperialist struggles occurring in Algeria and Vietnam than an organization whose bureaucratic hierarchy and allegiance to the Soviet Union were seen as intransigently Stalinist.12

If any general grievance united leftist students, militants, and young workers, it was opposition to Gaullist dirigisme, the government’s highly centralized political, economic, and cultural policy of planned modernization.13 The PCF and CGT were thus also implicated in this critique for their own rigid structures and roles as loyal opposition within dirigisme. When the protests and strikes erupted in May 1968, calls for autogestion (worker self-management) proliferated amongst leftists and radicalized workers as alternatives to the monopolistic arrangements between the state, parties, corporations, and unions.14 This was paralleled in the political realm through a process that Michel de Certeau characterized as a “capture of speech,” in which subjects ignored the institutionalized processes, media, and representatives of established political expression and experimented with new forms of direct democracy.15 Not only were protests, wildcat strikes, sit-ins, and occupations often beyond the control of parties or unions, but many were openly anticommunist. This was particularly the case amongst the so-called groupuscules of young activists of various gauchiste (“leftist”) tendencies—Maoist, Trotskyist, Situationist, anarchist—who sought more radically qualitative and immediately revolutionary goals than the PCF.16

The rebellious spirit of the gauchiste groups characterized the emblematic visual culture of May 1968, from the iconic posters and poetic graffiti that spread throughout Paris and other cities, to the sensational photos of rioting protesters. The specific ways these spectacular expressions of insurrection were differentiated from or replaced established media paralleled the circumvention of the authority of unions, political parties, or individual leaders.17

As the government reestablished order, the CGT jockeyed with other unions, such as the gauchiste-sympathizing Confédération française démocratique du travail (French Democratic Federation of Labor, CFDT), for control of the radicalized workers’ movement while the PCF struggled to address the recomposition of the French working class and new kinds of political demands that had emerged in May.18 Both organizations, however, pursued the same fundamental goals they had prior to 1968: the conquest of bread-and-butter concessions from the government and private businesses as opposed to calls for autogestion, and the formation of a united front of left-wing parties under the hegemony of the PCF, a goal that was realized from 1972 to 1977. One key move in this direction was the PCF’s tepid criticism of the Soviet Union’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968—a symbolic though not insignificant attempt to distance the party from charges of Stalinist subservience, and one which convinced sympathetic artists such as Pierre Bernard and Gérard Paris-Clavel to officially join.19

Individual and historical circumstances converged remarkably in the founding of Grapus, positioning it for the task of harnessing the energies of May 1968 to advance the goals of the PCF and CGT. Pierre Bernard and Gérard Paris-Clavel met François Miehe, a design student and Communist Party member, in the midst of the May events when they occupied and helped organize a silkscreen poster workshop in the École des Arts-Décoratifs, following the lead of artists and students at the École des Beaux-Arts who had established a poster workshop renamed the Atelier Populaire a few days earlier. As at the Beaux-Arts, poster design and production at the Arts-Déco was organized in collectivist fashion. Anyone could propose a design, while slogans were often solicited from union representatives. A daily general assembly would vote on designs which would then be silkscreened in assembly-line fashion and pasted to the walls of the Latin Quarter and other key sites. However, in contrast to the heavily attended general assemblies at the Beaux-Arts, the Arts-Déco gained a reputation for greater political homogeneity largely thanks to Miehe’s experience as a PCF organizer.20

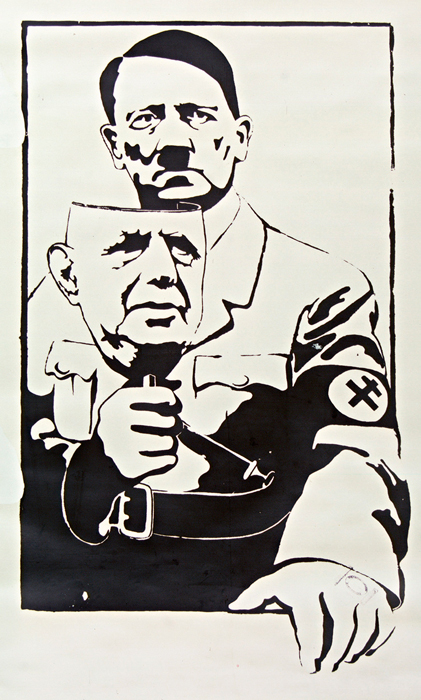

Correspondingly, there was more aesthetic consistency amongst the Arts-Déco posters than with the Beaux-Arts posters, which tended to emphasize slogans and display an explicitly childlike or cartoonish hand-drawn style. Arts-Déco posters, such as those designed or printed by the future members of Grapus, demonstrated a stronger graphic sensibility.21 A celebrated and notorious example is the one showing Hitler removing a de Gaulle mask (Figure 11.1). The absence of text and the realism of the depiction are shocking precisely because their mimetic competence makes it harder to associate the crude message with youthful zealousness or spontaneity. This stylistic proficiency is also apparent in another example in which a Gaullist cross is screwed into an outline of a head in profile. The economy of the design conveys a precision absent from most May 1968 posters.

Figure 11.1 Atelier des Arts-Décoratifs, 1968. Silkscreen poster. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Police shut down the Arts-Déco poster workshop at the end of June 1968, putting an abrupt end to Bernard, Paris-Clavel, and Miehe’s militant activity. At the university level, the immediate post-May period was characterized by attempts at institutional and pedagogical reform. One manifestation of this was the founding of a short-lived interdisciplinary school, the Institut de l’Environnement, in November 1969. It was within this experimental context that Bernard, Paris-Clavel, and Miehe regrouped to undertake a research project on the use of political media in the public sphere. Influenced by their reading of Roland Barthes’ semiology, they formed Grapus in 1970 to continue what they had done at the Arts-Déco in May and June 1968 on a more systematic basis. The name was a play on the insult, “crapule stalinienne” (“Stalinist scum”), which had been hurled at communists by gauchistes during and after May.

Grapus committed itself to working exclusively for left-wing political and cultural causes and organizations. In keeping with the ethos of the May 1968 poster workshops, Grapus operated as a collective entity. Members did not pursue individual projects but each commission and design was discussed and approved by the group. A central pillar of Grapus’s endeavor was, as Bernard explained, the “production of images of ‘pleasure,’ with the idea of thereby transmitting to activists the energy and desire to act.”22 This emphasis on pleasure was perhaps the most palpable impact of May 1968 on the reformulation of leftist identity. As countless commentators have noted, what was novel about the events was a reconfiguration of political values combining a social critique of exploitation and inequality with an aesthetic critique of repressed desire—class struggle combined with individual pleasure.23 Grapus’s posters would attempt to visually sustain this contradiction by picturing “pleasure” as an inclusive invitation to the viewer to partake in the process of imagining communism.

The lack of an established graphic design culture in France hindered Grapus’s case for appealing to political organizations such as the PCF. The state, parties, unions, and other organizations came up with text and slogans but typically left design considerations to the printer whose task it was to arrange the furnished content in the most legible way possible according to the established conventions of public media. Occasionally a sympathetic artist might be commissioned to produce an image for the organization but there was no systematic involvement of graphic design in civic life as existed in countries such as the Netherlands, Switzerland, or Germany and Grapus essentially sought to single-handedly carve this role for themselves. At the same time, the absence of institutionalized conventions in France left open the possibility for experiments launched in the heat of extraordinary political circumstances to fill the void. It also allowed Grapus to draw on and combine heterogeneous sources, from Tomaszewski’s aesthetics to classic French commercial designers such as Savignac to the posters and graffiti of May 1968.24

Through Miehe’s party connections, Grapus began to work with local chapters of the PCF on various campaigns. Several posters from 1971 and 1972 focus on promoting the formation of a union of the left under a common program and advertise public debates with PCF officials. These examples all eschew both the ouvriérisme (workerism) and national iconography of postwar modernization that characterized PCF (though not only PCF) propaganda prior to 1968. Instead, the posters employ disjunctive fonts and dynamic placements of text, features that would become hallmarks of the Grapus aesthetic. Often, this would involve a juxtaposition or playful interaction of typeset fonts with handwritten text that recalled the graffiti of May 1968. In several of these early posters, photographic imagery, rather than seeming to transparently depict subject matter, is stylized in such a way as to call attention to the mediation of visual expression. This is, for example, achieved through the filtering of the image through a colored and enlarged printing matrix, reminiscent of the exaggerated ben-day dots in Roy Lichtenstein’s comic book-inspired paintings. Notably addressing key post-May concerns such as women’s rights, the environment, or the media, these posters demonstrate the impact of Grapus’s reading of Barthesian semiology.

In his classic 1964 essay, “Rhetoric of the Image,” Barthes dissects an advertisement for pasta to explain how visual and textual signs are arranged to naturalize symbolic meanings for a given purpose. In Barthes’ reading, denotative meanings of a photograph, for example, of tomatoes, onions, pasta, a shopping bag, are used to support and convey connotative meanings (freshness, home cooking, “Italianicity,” etc.) which can then be “anchored” with the signifier of the brand.25 The cultural meanings transmitted are made to seem natural or unmediated because of their grounding in the transparency of denotative meanings which are “messages without a code.” In Grapus’s early PCF posters, photographs are presented in ways that inhibit immediate denotative readings through interventions such as color filters, distortions, and layers that present the image as inherently “coded.”

One such poster for the PCF analogizes this rhetoric of the image to comment on media censorship at the ORTF, the public radio and television agency (Figure 11.2).

A key issue raised by May 1968 protesters and addressed in numerous Atelier Populaire and Arts-Déco posters, including those designed by future Grapus members, was the government’s manipulation of information at the ORTF. Gauchistes called for its dissolution as a mouthpiece of repressive state propaganda and supported the continuation of a major strike by ORTF workers in June 1968.26 In explicit contrast to state-run radio and television, graffiti, silkscreened posters and “wall journals” were positioned as more authentic, spontaneous, and unmediated forms of communication.27 The PCF, however, adopted a reformist position and encouraged a negotiated end to the ORTF strike, predictably prompting charges of counterrevolutionary collaboration from gauchistes.28 Grapus’s 1972 poster calling for “democratization” of the ORTF incorporates the May 1968 critique of censorship while challenging the notion of unmediated communication. A blue-tinted photograph of a protest by ORTF workers is partially overlaid with a rectangular box which further distorts the image, representing the graininess of a television screen. The mouths of individuals within the box are blacked out and the words “scandales censures arbitraires” (arbitrary censorship scandals) appear in white. Black-on-white text appears diagonally below the television screen box, reading, “To reclaim the ORTF, it must be democratized.” This text is printed as if collaged, ransom-note style, from cut-out fragments, an explicit rejection of professional typesetting and evoking the creative manipulation of official information. As such, it visually creates a distinction between the official language, or what Ferdinand de Saussure termed langue, and a specific speech act, which Saussure termed parole.29 The tinted photograph and collaged text present visual and textual information as always already mediated, yet subject to manipulation. The poster thus adopts the PCF’s reformist position by demanding that journalists and editors be given more say over content rather than proposing an alternative, more spontaneous, or “freer” form of communication. Barthes’ dissection of advertising rhetoric, and particularly the use of photography in advertising, provided Grapus with a powerful theoretical tool with which to develop strategies to advertise for a political cause while critiquing the codes of commercial advertising.30

Even the ORTF poster, however, is uncommon for Grapus due to its representation of worker militancy, redolent of the pre-1968 masculinized ouvriérisme that characterized the PCF and CGT and which was subjected to feminist critique after May 1968.31 Not only is there a notable prevalence of posters specifically addressing women’s rights, but in the few images of workers that the group designed, such as in the logo for the Paris chapter of the CGT, gender is ambiguously or diversely represented (Figure 11.3).

Figure 11.3 Grapus, CGT, Paris, 1973. Offset print poster. Courtesy of Pierre Bernard.

The 1972 logo depicts four abstracted figures of indeterminate gender embracing each other and supported by the massive letters CGT. Behind the figures, a simplified silhouette of the Eiffel Tower with pillowy clouds floating by conveys an image of urban optimism. One of the two clouds, however, is positioned behind the head of one of the figures and simultaneously reads as windblown hair. That this element is present in earlier proposals for the design, before the inclusion of the Eiffel Tower and other clouds, supports the suggestion that the figure is a woman. Furthermore, the traditional signs of worker solidarity and militancy, such as the raised fist, handshake, or picket sign—still evident in many May 1968 posters—have been replaced by the affective touching of supportive bodies which together form a unified yet informal mass with the rightmost figure resting a relaxed arm over the top of the “T.”

The move towards a graphic language of pleasure became more pronounced with the formation of the Union de la Gauche (Union of the Left) in 1972. This coalition of leftist parties had been one of the PCF’s major political objectives both prior to and after 1968. However, frictions surfaced almost instantly as the PCF and the more modernate Socialist Party (PS) attempted to outmaneuver each other for electoral gains and ideological control within the union.32 The Socialists, embracing the gauchiste rhetoric of autogestion, made significant gains in the 1974 presidential election. The PCF hastily organized the 21st Party Congress in which General Secretary Georges Marchais outlined a new platform for the coalition, entitled Union du peuple de France (Union of the People of France), as an attempt to outflank the Socialists’ appeal to younger workers and gauchistes.

According to Marchais, the ranks of clerical and managerial workers that had swelled in the postwar period would eventually gravitate to the communists as they became conscious of their status as waged labor. Though continuing to grant political primacy to the industrial working class, Union du peuple de France included within that category technicians, engineers, and other intellectual workers who had previously been classified as “white collar.” Many of these workers had been students in 1968, were politicized by concepts such as autogestion, or were simply impacted by the cultural transformations spawned by the May movement. They were thus more inclined to identify with the less traditionally Marxist dimension of revolt expressed in celebrated 1968 graffiti such as “sous les pavés la plage” (“beneath the paving stones lies the beach”).

Grapus’s designs for the Union du peuple de France campaign marked its fullest involvement with the PCF and resulted in some of the collective’s most widespread imagery, consisting of a childlike drawing of a radiating sun with Union du peuple de France pour le changement démocratique (Union of the People of France for Democratic Change) in the simple handwriting that was becoming a hallmark of the group’s style (Figure 11.4).

As Bernard explained, “We had a theory that handwriting would be better than typography at making it easy for the observer to make the message his or her own.”33 Thus the indexicality of handwriting was intended to refer to an expressive subject rather than a bureaucratic organization. Like the graffiti and posters of May 1968, the handwritten style was meant to distinguish itself from both commercial advertising and official political imagery. “After all,” Bernard noted, “typography is associated with the world of products and institutions. We thought we were taking a step towards a general image for the party.” This general image avoided any specific markers of class or gender while proposing a youthful, vibrantly humanistic sensibility for an organization that was continuing to characterize itself as the revolutionary party of the working class, albeit one that could accommodate an expanded definition of that identity. Grapus’s Union du peuple de France design—produced for posters, billboards, brochures, stickers, buttons, T-shirts, and even membership applications—suggested that the Communist Party in fact led the way to the beach that had been glimpsed in May 1968.

The posters Grapus produced for the PCF in the mid-1970s extended the playful cheeriness of the Union du peuple de France imagery, often combining it with countercultural elements such as their poster depicting Marx as a hitchhiking hippie, thumb pointing left, for the party’s youth movement. Grapus’s expectation that such “images of pleasure” might become the “general image” of the French Communist Party appears, at least in retrospect, as naïvely hopeful as the message these images communicated. And yet they highlight the complex and uncertain position that the PCF, and indeed the French left in general, found itself in after 1968.

In May 1968, students and workers of vastly different circumstances sought to transcend the distances between their social and spatial locations.34 The paradox was that while the antagonists they targeted were the historical organizations and institutions of class politics, the common ground they found was the inherited language of class struggle; 1968 thus appears, in retrospect, as the last gasp of a shared language of the left.35

The Union de la Gauche was an attempt to face this challenge, yet it contributed to the further fragmentation of the left as communists and socialists now jostled for control of an increasingly amorphous demographic. Under criticism and internal dissent over its continuing loyalty to the Soviet Union following the French publication of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, the PCF abandoned its commitment to the “dictatorship of the proletariat” in 1976 and affirmed a democratic route to socialism. However, in the 1976 elections, the PS gained considerably more seats than the PCF. Conflicted about whether to continue to liberalize or whether to consolidate its traditional yet shrinking base, the PCF chose both, openly criticizing the Soviet Union and flirting with Eurocommunism while denouncing the PS’s “right-wing turn” and quietly scrapping the Union du peuple de France.

Grapus’s celebrated 1977 poster for the PCF’s youth organization (Figure 11.5) can be seen as an attempt to negotiate this uncertainty by integrating 1968-inspired tropes of spontaneity and individuality into official party propaganda.

Block letters reading ON Y VA (Let’s Go) appear in a spectrum of colors against a black ground. Despite the letter’s typographical precision and boldness, the status of the phrase is slightly ambiguous, its tone depending on whether one reads the color scheme as suggestive of sunrise or sunset. As if to intervene in this uncertainty, handwritten letters in white play around the block letters, directing the phrase towards more specific meanings by incorporating certain letters of the original phrase into a new one reading ON Y VA Tous à IVRY à la fête Vers le changement! (Let’s all go to Ivry for the festival towards change!). The handwriting personalizes the expression as indices of individual spontaneity in the vein of May 1968 graffiti and poster détournement.

Tom McDonough has described détournement, the key critical strategy developed by the Situationist International, as “the production of an unalienated writing” that could overcome the impasse of postwar leftist political expression.36 This impasse was exemplified, McDonough argues, in Roger Garaudy’s 1951 description of communist propaganda which, according to Garaudy, was characterized by “its simplicity and purity,” and in which “words stick close to facts and actions.”37 Because détournement re-routed the meanings of disparate utterances by introducing play, fragmentation, and polyphony into a text, it constituted, according to Guy Debord, “the flexible language of anti-ideology.”38 Détournement’s uncoupling of signs from their dominant ideological significations was seen as the invention of a new language—a dialectical one that “knows it cannot claim to embody any inherent or definitive certainty,” unlike Garaudy’s description of the transparency of party propaganda.39

Grapus’s On y va poster draws on the aesthetics of détournement to challenge the authority of the standardized typeface in the same way that the Situationists, and Situationist-inspired protesters in 1968, challenged the orthodoxy of the Communist Party’s language and its ability to transparently represent social truth. And yet, that party language is also Grapus’s, who are in essence enacting a détournement of their own poster for the PCF. Rather than a critical strategy of dialectical negation, Grapus’s use of détournement reaffirms and specifies the party’s message, but in a way that could address the split in the post-1968 leftist subject.

The use of détournement acknowledges the tension between “old” and “new” left, refusing to synthesize the two. This is in contrast to the image of the hitchhiking Marx from the earlier poster for the Mouvement de la jeunesse communiste (Communist Youth Movement), which reappears as a small icon in the upper right corner of the On y va poster. In fact, the party had rejected an earlier design for the poster featuring a hippie Lenin. Attempting to balance the pressures of democratization and de-Sovietization with the necessity of averting Socialist Party dominance of the left, the PCF’s language required all the flexibility that their pre-1968 propaganda had denied.

The Union de la Gauche had been an attempt to articulate a broad leftist political force in the wake of 1968. However, what leftist politics consisted of became increasingly unclear, particularly as the economic crisis of the mid-1970s further split the PCF and PS on issues such as nationalization of industry and the minimum wage.40 As issue-specific forms of political identification increasingly characterized the French electorate, the PCF’s continued insistence on the primacy of economic questions appeared outmoded to scores of younger voters whose political horizons had multiplied during and after 1968. The socialists’ flexibility in this regard made them more appealing to ex-gauchistes and centrists alike. The Parti Socialiste, born after May 1968 and having less of an established image or identity to reinvent, was better adapted to the post-1968 environment. In the fall of 1977, the Union de la Gauche collapsed and the PCF renewed its ouvriériste orientation, alienating many reformers within the party.

By many accounts, 1978 was the year French Communism suffered its decisive defeat.41 The failed Union de la Gauche, rather than bringing the PCF to power, had only legitimized the PS as a non-communist left-wing alternative. The collapse of a united front predictably split the left vote, and the governing center-right maintained its majority. For the first time since 1936 the Communist Party received fewer votes than the Socialists.

That same year, founding member François Miehe left Grapus as financial and ideological pressures began to mount. The group designed numerous further posters for PCF and CGT campaigns and communist-dominated municipal councils, particularly in the “red belt” of working-class suburbs surrounding Paris. Though frequently employing the combination of typeset with handwritten text that had become a signature of their style, they largely abandoned the pursuit of a new general image for the party and began to take on more commissions for cultural organizations. As Jean-Paul Bachollet, who joined the group in 1976, put it, “The French Communist Party does not want that we, Grapus, renew its image, since the party itself has no idea what image it should have.”42

The socialists’ political victory in the 1981 presidential elections prompted the appointment of communists to ministerial posts for the first time since their banishment from the government in 1947 and gave new hope to a left that had struggled to define itself in the aftermath of 1968. However, now more directly under the thumb of the PS, the PCF saw its support shrink even more rapidly than it had during the 1970s and they chose to leave the cabinet in 1984 as François Mitterrand’s government pivoted further rightward.

That same year, Grapus ended its collaboration with the PCF and CGT, and with it the attempt to update the image of the party by fusing the energies of May 1968 with the historical organizations of the left. And yet, the longevity and productivity of the collaboration is remarkable. Grapus’s commitment to the Communist Party stands in marked contrast to the dominant characterization of the era as one of cultural rebellion against traditional institutions. The case of Grapus reveals that the post-May period, rather than witnessing a flight from politics, saw sustained experiments in articulating a new political language, one informed by critical theories of representation, collectivist ethics, and countercultural styles, which instead of seeking to overcome the contradictions and contingencies of transformative historical processes, sought images that allowed space for the viewer to feel that she had a role to play.

1 Kim Willsher, “French Communist Party Says Adieu to the Hammer and Sickle,” The Guardian, (February 10, 2013) http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/feb/10/french-communist-party-hammer-and-sickle.

2 The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe, Vol. 2: 1870 to the Present, ed. Stephen Broadberry and Kevin H. O’Rourke (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2010), 210–211.

3 A clear narrative account and assessment of the interpretations of the student-worker protest movement and general strike of May–June 1968 is provided in Michelle Zancarini-Fournel, Le moment 68: Une histoire contestée (Paris: Seuil, 2008).

4 Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “The Group That Was (Not) One: Daniel Buren and BMPT,” Artforum International, 46, No. 9 (May 2008): 310–314; Sami Siegelbaum, “The Riddle of May ’68: Collectivity and Protest in the Salon de la Jeune Peinture,” Oxford Art Journal 35, no. 1 (2012): 53–77.

5 Guy Debord and the Situationist International, ed. Tom McDonough (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002); Vincent Kauffman, Guy Debord: La révolution au service de la poésie (Paris: Fayard, 2001).

6 Catherine Millet, Contemporary Art in France, trans. Charles Penwarden (Paris: Flammarion, 2006), 117–155; Raphael Rubenstein, “The Painting Undone,” Art in America 79, no. 11 (November 1991):134–143, 167.

7 Hugues Boekraad, My Work is Not My Work: Pierre Bernard, Design for the Public Domain (Baden: Lars Müller, 2008), 104–105; Jacqueline Wesselius, “Grapus: The Image of Pleasure and the Pleasure of the Image,” in Grapus 85 (Utrecht: Reflex, 1985) n.p.; François Barré, “Grapus: A Poster Designer’s Collective,” Graphis 213 (1981): 58–63.

8 Tomaszewski’s posters broke with both the official dictates of Socialist Realism and modernist orthodoxies by developing a dynamic fusion of text and image, while also emphasizing spontaneity, playfulness, and irregularity through, for example, simple freehand-drawn elements. Rhetorically, what particularly struck Bernard and Paris-Clavel was how Tomaszewski’s posters for films, theaters, and cultural events communicated meaning through the design itself rather than using design as a means to transparently arrange or present information about pre-existing meanings or referents. See The Master of Design: Pierre Bernard, ed. Jianping He (Singapore: Page One, 2006), 9–11.

9 Leo Favier, Comment, tu ne connais pas Grapus? (Leipzig: Spector Books, 2014). However, all of the primary former members of Grapus continued to pursue the original mission of graphic design in the service of socially progressive political causes. Bernard founded the Atelier de création graphique (Graphic Design Workshop) while Jordan founded Nous travaillons ensemble (We Work Together) as quasi-continuations of Grapus. Paris-Clavel helped establish the activist design group Ne pas plier (Do Not Bend). Miehe continued to design posters for political causes such as Palestinian liberation and nuclear disarmament.

10 Already prior to 1968, however, the PCF had confronted emerging challenges as, domestically, it opposed Gaullist modernization as exploitative while promoting it as essential to working-class unity and, internationally, it continued to obey the Soviet Union’s directives, refusing to support many anti-imperialist liberation struggles that were finding increasing favor amongst French intellectuals and leftists. See Mark Poster, Existential Marxism in Postwar France: From Sartre to Althusser (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975), 39–42.

11 Enrollment in French universities increased by over 200 percent during the 1960s (James D. Wilkinson and Stuart H. Hughes, Contemporary Europe: A History, 8th edn. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 1998), 426).

12 See, for example, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, Le Gauchisme: Remède à la maladie sénile du communisme (Paris: Seuil, 1968).

13 “Gaullism” refers primarily to the policies of the French state under the leadership of Charles de Gaulle (in office 1958–1969), which attempted to modernize the economy through a program of centralized incentives to private industry.

14 On this topic see Ruth Erickson’s contribution to this volume.

15 Michel de Certeau, La prise de parole, et autres écrits politiques (Paris: Seuil, 1994).

16 Though drawing on a variety of historical currents in leftist thought, postwar gauchisme can be seen as a reaction to four key historical factors particular to France: 1) the centralized paternalism of the French state under Charles de Gaulle; 2) the agonized experience of decolonization; 3) the rapid growth in university student and non-industrial worker populations; and, 4) the perceived sclerosis of the PCF. See, Kristin Ross, May ’68 and Its Afterlives (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 8.

17 See Ross, May ’68 and its Afterlives, and Jean Baudrillard, “Requiem for the Media,” For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign, trans. Charles Levin (St. Louis, MO: Telos, 1981), 164–184. Despite the frequent association of the celebrated silkscreen posters produced at the occupied art schools and other sites with gauchisme, there were virtually no posters produced which were overtly critical of the PCF or CGT. For information about the silkscreen poster workshops of May ’68 see Mai 68: les mouvements étudiants en France et dans le monde, ed. Genevieve Dreyfus-Armand and Laurent Gervereau (Nanterre: BDIC, 1998). On the association between the silkscreen posters and gauchisme see Victoria H. F. Scott, “May ’68 and the Question of the Image,” Rutgers Art Review 24, (Fall 2008); and Michael Seidman, The Imaginary Revolution: Parisian Students and Workers in 1968 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2004), 91–161.

18 George Ross, Workers and Communists in France: From Popular Front to Eurocommunism (Berkeley: University of California, Press, 1982) 215–223.

19 The Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968, ending a period of democratic liberalization under the government of reformer Alexander Dubček.

20 “L’atelier des Arts décoratifs. Entretien avec François Miehe et Gérard Paris-Clavel,” in Dreyfus-Armand and Gervereau, Mai 68, 192–193.

21 Like the Atelier Populaire at the Beaux-Arts, the Arts-Déco workshop maintained a strict ethic of anonymity in poster design. However, certain designs have subsequently been attributed to individuals such as Bernard (see Rick Poynor, “Utopian Image: Politics and Posters,” Design Observer 3/10/13 (http://designobserver.com/feature/utopian-image-politics-and-posters/37739/)). Nonetheless, all designs were subject to general assembly approval and modification and were considered collective productions.

22 Pierre Bernard, email to author, 3/4/2015.

23 For an analysis that reads May 1968 in terms of an irruption of hedonistic individualism, see Jean-Pierre Le Goff, Mai 68, l’héritage impossible (Paris: La Découverte, 2006). The notion of May 1968 as a combination of “social” critique and “artistic” critique is advanced by Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello, Le nouvel esprit du capitalisme (Paris: Gallimard, 1999), 241–251. For a reading of May 1968 as a transition from the dominance of political economy to concerns over personal rights, see Julian Bourg, From Revolution to Ethics: May 1968 and Contemporary French Thought (Montreal: McGill-Queens University, 2007), 19–44.

24 Raymond Savignac (1907–2002) was a celebrated French commercial graphic designer prominent in the 1940s and 1950s, known for his simple and humorous advertisements for consumer products.

25 Roland Barthes, “Rhetoric of the Image,” in Image, Music, Text, ed. and trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 32–51.

26 The ORTF strike was one of the longest and most politicized, lasting from mid-May until early July.

27 See Sami Siegelbaum, “Authentic Mediation: Art, Media, and Public Space in May ‘68,” Kunstlicht 32, no. 3 (2011), 39–49.

28 Jean-Pierre Filiu, “La crise de l’ORTF en mai-juillet 1968,” Bulletin du comité d’histoire de la télévision (January 1986).

29 Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, 3rd edition, trans. Richard Harris (Chicago: Open Court, 1986), 9–15.

30 Also instrumental for Grapus in this regard was Serge Tchakhotine’s Le Viol des foules par la propagande politique (translated into English in 1940 as The Rape of the Masses: The Psychology of Totalitarian Political Propaganda), first published in 1939 and suppressed during the occupation. It was republished in the early 1950s and its psychological analysis of propaganda became highly influential. Pierre Bernard, email to author, 3/4/2015.

31 The PCF’s position on la condition féminine (the status of women) pre-1968, while progressive compared to other political parties, was stringently economistic and often outright scornful of the sorts of concerns raised by the nascent women’s movement. After 1968, the women’s movement became a key test case for the PCF’s ability to address expanded political concerns. See Jane Jenson, “The French Communist Party and Feminism,” The Socialist Register 17 (1980): 121–147; and Michel Garbez, “La question féminine dans le discours du parti communiste française,” in Discours et Idéologie (Paris: PUF, 1980), 301–393.

32 The PS was founded in 1969, largely replacing the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) whose reputation had suffered from indecisiveness on Algerian independence and compromises with Gaullism.

33 As quoted in Boekraad, My work is not my work, 105–106.

34 See Ross, May ’68 and its Afterlives, 2-18.

35 As philosopher Alain Badiou has recently noted, despite the disagreements between various factions in May 1968, “everyone spoke a common language, and the red flag was everyone’s emblem,” but that despite its amazing efflorescence in May, this language was “beginning to die out because May ’68, and even more so the years that followed, was a huge challenge to the legitimacy of the historical organizations of the left, of unions, parties and famous leaders.” Alain Badiou, “May ’68 Revisited, 40 Years On,” in The Communist Hypothesis, trans . David Macey and Steve Corcoran (London: Verso, 2010), 41–42.

36 Tom McDonough, The Beautiful Language of My Century: Reinventing the Language of Contestation in Postwar France, 1945–1968 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 25. Détournement was defined by the Situationist International as “the integration of present or past artistic productions into a superior construction of a milieu.” “Definitions” (1958), in Situationist International Anthology, ed. and trans. Ken Knabb (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 1981), 45. Typically, this has been understood as the re-routing of messages towards new critical ones through the manipulation of existing or appropriated visual and textual elements.

37 Roger Garaudy, “Propagande de guerre et propagande communiste,” La Nouvelle critique (March 1951), quoted in McDonough, The Beautiful Language of My Century, 43.

38 Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle (1967), trans. Ken Knabb (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, n.c.), §208.

39 Ibid.

40 Ross, Workers and Communists in France, 266–267. D. S. Bell and Byron Criddle, The French Communist Party in the Fifth Republic (Oxford: Clarendon, 1994), 104–107.

41 Bell and Criddle, The French Communist Party in the Fifth Republic, 99–107; Bernard Puda, Un monde défait: Les communistes français de 1956 à nos jours (Broissieux: Croquant, 2009), 99–106; Ross, Workers and Communists in France, 280–298.

42 Wesselius, “Grapus,” n.p.