Know most of the rooms of thy native country before thou goest over the threshold thereof. Especially seeing England presents thee with so many observables.

Thomas Fuller (1608–61), English clergyman and historian, The Holy State and the Profane State (1642)

It was on a train to Newcastle from King’s Cross, to write an article about Britain’s oldest Marks and Spencer, in the city’s Grainger Market, that I first thought of writing this book.

About a quarter of an hour before we pulled into Durham, I headed for the buffet. When I got back to my window seat, at a table in the quiet carriage, a middle-aged man in a tweed jacket in the row of seats behind me leant over and said, in a polite but jaunty way, ‘I’m very sorry to disturb you, but are you a geographer?’

An odd question, I thought, forgetting that I had left a copy of L. Dudley Stamp’s Britain’s Structure and Scenery open on the table when I went to the buffet.

‘We’re both geographers,’ he said, gesturing to a smartly dressed man of about the same age, sitting next to him, ‘and Stamp is the absolute classic. We all read it at university.’

The two men turned out to be the Reverend Ian Browne, a geography graduate and chaplain at Oundle School, Northamptonshire, and his common room colleague, Gary Phillips, the school registrar. They were off to Edinburgh to give a sermon and a lecture respectively.

We chatted a bit about the late Sir Laurence Dudley Stamp, Professor of Geography at Rangoon and London, and one of the leading British geographers of the twentieth century.

‘And so,’ I asked, as the train headed towards Durham, ‘can you look at any view in Britain and see why it looks like it does?’

‘Just about,’ said the chaplain. ‘So that,’ he said, pointing to a bulging green ridge running along the top of a hill next to the train, ‘is the typical sort of landscape you get with sandstones from Coal Measures.’

‘It’s the same sandstone they used to build the cathedral,’ said Gary Phillips, as we pulled into Durham, with that tremendous view of the cathedral to our right. ‘It’s usually a dull buff colour but, in the chapel of Durham Castle, it’s a lovely golden brown with a terrific watermark on it,’ he added, pointing towards the castle.

I swapped addresses with them and returned to my seat to read my book. How lovely, like Sir Laurence Stamp, and my two new geographer friends, to know how the wind, rain, frost, snow, ice, streams, rivers and sea have sculpted the earth’s crust for millions of years.

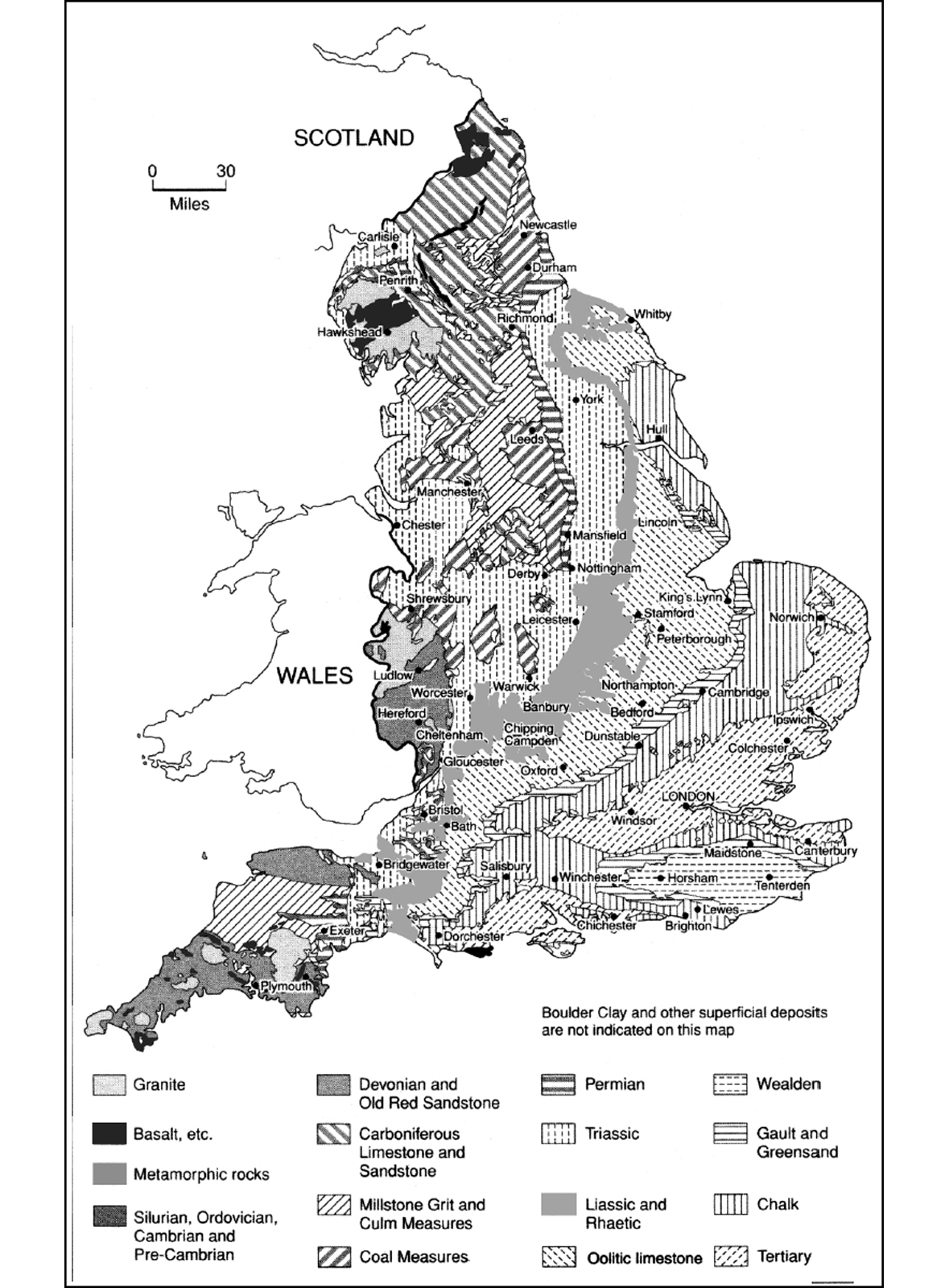

The extreme variety of the English landscape was largely created by chunks of raised sea bed and fragments of land mass that began life south of the equator 600 million years ago, and gradually migrated north. Britain is a random collection of soils and stones, flipped over by tectonic grating, frozen by ice ages, sculpted by volcanoes, fried by the sun, sometimes swamped by the sea, sometimes lifted above it.

Across the country, you can see various vivid stages in these processes. Off the Norfolk coast, there are 5,000-year-old tree trunks, survivors of the dense forest that covered much of the country before the land bridge to Europe was inundated with melted ice. Several of those trunks are still scored with the teeth marks of Mesolithic beavers. Stones on the Isle of Wight are still stamped with dinosaur footprints.

No other country in Europe packs so many different stones into such a small area as Britain does. In a thirty-mile journey, you’ll come across as many different landscapes as you might cover in 300 miles in a blander, more geologically uniform country like, say, Canada, Australia or America.

To identify those different geological landscapes, it’s useful to remember that the different layers of stone tend to dip downwards along a line running across England from north-west to south-east. Up in the north-west, the lowest stones in the sandwich – the oldest ones – are pushed towards the surface; while, in the south-east, those lowest stones are tipped deeper down, leaving newer stone at the top.

Northamptonshire’s layers of stone have been compared to a deck of playing cards splayed on a table, with the oldest strata exposed at one end, the newest at the other. Where rivers cut through these layers – as the Rivers Nene, Tove, Ouse and Ise do, in Northamptonshire – the oldest strata are exposed at the bottom, the newer ones revealed further up the sides of the valley. River valleys also expose the chalk underbed of Suffolk, otherwise concealed by clay, sand, gravels and glacial sands.

The tectonic plate on which England sits is still dipping south-eastwards, tipping us, very slowly, into the Channel: the coast around the Thames estuary is sinking at around a foot a century, while Scotland is slowly rising.

England is still moving on the surface, too. After the floods that devastated Cockermouth in the Lake District in 2009, millions of tons of gravel were scattered across the fields on the valley floor, either side of the River Cocker. The rivers hopped out of their normal course and meandered down the middle of the valley.

You tend to find better stone in the west – in the central limestones, the West Midlands sandstones, and the ancient granites, slates and sandstones of the West Country.

As you move east, the stones not only get younger, but their quality also lessens. The Jurassic sandstone of Dorset, topped with limestone, gives way a few miles east to rock with a later sandwich of inferior materials above it – shales (rock made from clay mud, spotted with minerals), marls (a sort of chalky clay), clays and ironstones. East Anglia, the south-east and the south are largely made of clays, sand, shales and chalk.

This eastward, reverse-ageing process continues until you reach the south-eastern coast at Dover. The White Cliffs are made of chalk – a much younger material than all those rocks further west. A soft, porous, white limestone, chalk is responsible for more quintessential English landscapes than any other single rock.

As well as forming the White Cliffs of Dover and the outcrop on which Windsor Castle perches, chalk produced the landscapes of the North and South Downs and Salisbury Plain, the biggest stretch of unploughed chalk downland in the country. Mineral-rich chalk soil deepens the gaudily streaked colours of autumn leaves in Sussex – just as dramatic as New England in the fall. Old man’s beard, too, thrives on hedges grown in chalk soil.

The quality of agricultural land produced by chalk varies: from fertile arable land to fescue downland with short grass and unploughable, thin soils, to steep hills that develop into hanging beech woods.

High Wycombe’s chair-makers were well-placed for the hanging beech woods of the Chilterns – ideal for making the back spindles, legs and stretchers of Windsor chairs. Beech trees, found in England for 8,000 years, originally grew only in the south – Burnham Beeches, Buckinghamshire, now has the biggest collection of pollarded beeches in the world. But they have spread north over the millennia: a great stand of them now acts as a shelter belt in the Pennines.

Chalk provides the best foundation for typical English sporting pursuits, too. Cricket was supposedly first played on the short, downland grass of the chalk downs of southern England, with balls made from woollen rags. In this rather romanticized view – which puts sheep, the motor of England’s economy for centuries, at the heart of the narrative – shepherds used the wicket gate of the sheepfold as the wicket, and their crooks for bats.

Downland is ideal racing and training country, notably at Epsom, Surrey, and on the Berkshire Downs. The chalk of the Berkshire Downs, around the racing Mecca of Lambourn, produces springy grass and a softish falling surface, unlike bone-rattling clay. The chalk wolds in Yorkshire, around Malton, are similarly accommodating.

Leicestershire is hunting country, too – the Quorn is England’s most famous hunt, in part because of the zinginess of the light soil, compared with the heavy clay soil of southern vales; taking a fence on the Laughton Hills near Market Harborough is like jumping off springs.

Chalk streams produce the best fishing in England; and there are more chalk streams in England – 161 of them – than in any other country. It is chalk that makes the fishing rivers of Wiltshire and the Hampshire Downs: the Avon, the Itchen, the Meon and the Test. Fed by underground aquifers, chalk streams are rich in the calcium which feeds crayfish, water snails and shrimps; the streams are also filled with plant nutrients, like nitrates, phosphates and potassium, ideal for the mayfly.

The effect of a chalk bed on the landscape varies. Much of the foundation of Norfolk is chalk, but the county barely resembles the North and South Downs – equipped as they are with the smooth, rolling chalk landscape of legend, with gentle curves cut into the hillside and broad, spreading humps swelling across the horizon, as if moulded by some celestial, shallow-bladed ice cream scoop.

That archetypal chalk landscape look is so distinctive that William ‘Strata’ Smith (1769–1839) – called the Father of British Geology – could see, on his first visit, that the Yorkshire Wolds were made of chalk from twenty miles away. He sensed chalk in the broad outline of the land and the smooth, rolling, waterless valleys, quickly drained by chalk’s porousness.

More often than not, war artists, in search of a tender, rural, threatened view of England, picked chalk downland for a backdrop. On the eve of the Second World War, Eric Ravilious kept returning to the ancient hillside chalk figures carved into the soft contours of classic English downland, among them the Wilmington Giant, near Eastbourne, the Uffington White Horse, Oxfordshire, and the Cerne Abbas Giant, Dorset.

There are two notable Raviliouses of the Westbury Horse, Wiltshire – one from a train, one with a train chuffing along in the background. By the 1930s, the railway – originally considered an interloper into the landscape – could be seamlessly absorbed into an archetypal image of the English countryside.

The Uffington White Horse is raised up high on the north side of the Ridgeway. The 5,000-year-old road – the oldest in Europe – is dictated by geology, as it runs along a 700ft-thick band of chalk stretching for eighty-seven miles from Ivinghoe Beacon in the Chilterns, near Tring, Hertfordshire, down to Overton Hill, near Marlborough, Wiltshire.

That band of chalk slips under the Thames and the River Kennet, before cutting through the New Forest. It dips under the Channel beneath the Solent and Spithead, and then raises its head above the water at the western end of the Isle of Wight. There, at Alum Bay, the chalk reappears in candy-coloured stripes.

The connection between chalk downland and quintessential England is made explicit in the morale-boosting Second World War poster painted by the War Office artist Frank Newbould. Above the caption, ‘Your Britain, Fight for it now’, the poster has a chalk landscape for its backdrop, with a shepherd and his dog leading sheep towards a farm nestling in a fold of the South Downs.

Other posters in the ‘Your Britain’ series showed Salisbury Cathedral and a country fairground in the shadow of a medieval village church, with a Gothic broach spire. Most British troops fighting on the Continent came from our industrial towns and cities, but the propaganda link identifying England with rural England – and the patriotic images do tend to be English, rather than British – still went unquestioned.

Of all the geological factors that have shaped England and the English, the most powerful is the fact that we live on an island off the edge of a vast land mass, moored between the Atlantic and the North Sea.

Our island nature is at the heart of our character. It doesn’t take much of a leap to connect a small, overpopulated island to a reserved, private population obsessed with class and horrified by intrusion.1

The English Channel – used as a highway and a barrier – made England. Our island status looms large in our view of ourselves – thus the affection for Shakespeare’s lines in Richard II: ‘This precious stone set in the silver sea, Which serves it in the office of a wall, Or as a moat defensive to a house, Against the envy of less happier lands, This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England’.

Foreigners, too, are struck by our island status. Britain was made ‘that fortunate day when a wave of the German Ocean burst the old isthmus which joined Kent and Cornwall to France,’ said the American writer Ralph Waldo Emerson in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Emerson’s romantic line is pretty much true. England was once connected to the Continent by a band of chalk that let the first immigrants stroll into England at the end of the Ice Age; only for rising sea levels to cut off the land bridge.

The island is still changing shape – tens of thousands of acres have been added to the English land mass in the last 1,500 years, particularly in the saltmarshes around Essex and the Wash.2 Further north, the English land mass is shrinking: the forty-mile stretch of Holderness coast, in the East Riding of Yorkshire, has the highest rate of erosion in Europe, with the coast retreating at around two metres a year.

Thirty per cent of the English live within six miles of the coast. And no one in England is more than seventy miles – or two hours’ drive – from the sea. But that doesn’t mean we’re forever taking day trips to the coast. We may be an island race but we’re now an island race that largely turns its back on the sea.

One reason why London has become the residence of choice for the global rich in the last decade is its geographical position – a civilized, democratic stopping-off point for Muscovite oligarchs on their way to New York; a temperate refuge from Arabian summer heat for Saudi billionaires. But you’re unlikely to find either group making their way to the coast.

For all our closeness to the sea, most major English cities tend to be some way from it – unlike major coastline cities like, say, Hong Kong or Los Angeles, or, for that matter, Cardiff, Belfast or Dublin. English cities are more likely to be on a major river, at a spot where the river has narrowed enough to be forded.

Over the last two centuries, the Industrial Revolution, rather than the sea, has dictated the size and importance of English cities. Of the top ten most populated English cities, only Liverpool, the sixth biggest, and Bristol, the eighth biggest, are maritime cities.

Even international maritime cities turn from the sea now. New Yorkers look inwards towards the raised spine of Manhattan, away from the Atlantic, and the Hudson and East Rivers; even though the island is only 2.3 miles at its widest. Until very recently, both the east and west shorelines of New York were pretty much inaccessible, cut off by highways and piers.

The British coast isn’t quite as inaccessible as that – although Londoners have largely lost touch with the Thames, since the construction of the Embankment in the 1870s. Sir Joseph Bazalgette’s engineering solved London’s sanitation problems – the new Embankment helped to conceal 1,300 miles of new sewers – but it also meant Londoners couldn’t wander down to the river so easily.

Like New Yorkers, the modern English remain for the most part landlubbers, seaside holidays apart. The Industrial Revolution – together with the invention of planes, trains and cars – means we have turned increasingly to the land, not only for our transport, but also for our livelihoods.

We now have very little of the reverence for – or fear of – the sea once shared by most inhabitants of this island: Anglo-Saxon poets treated England as the quintessential harbour; with rural England a haven from the wild sea. It’s true that 95 per cent of British imports still arrive by sea, but how many of us ever see them turn up? In 2009, only 26,700 Britons worked on water. These days, most of us only use the sea as a holiday site and our main drain.3

For all the talk about us being an island race, the island we’re on is in fact a pretty big one – the ninth biggest in the world, the biggest in Europe, and the third most populated in the world, after Java, Indonesia, and Honshu, Japan.

Bill Bryson should really have called his book Notes from a Pretty Big Island Surrounded by Lots of Smaller Ones – the British Isles are made up of 1,374 islands. The vast majority of us live on the big one in the middle – and most of us rarely see the sea from day to day.

Still, however little we might see the sea or earn our livelihood from it, the very fact of our being an island race deeply affects other countries’ opinion of us, and our opinion of ourselves; and those opinions are enough in themselves to make us different.

Our island nature doesn’t make us exactly xenophobic. The English have on the whole been pretty good at absorbing incomers from the Romans, via the Vikings, Normans, Huguenots, through to Jews, West Indians, Asians and Eastern Europeans.

But, still, the English remain fundamentally awkward with strangers – whether they’re foreign or English – not least because of their island isolation. It’s no coincidence that ‘insular’ comes from the Latin for island.

The English may complain about foreigners; yet, when they live next door to them, they’re perfectly polite, as long as they don’t have to cross each other’s thresholds. The cramped conditions that come from sharing a heavily populated island mean that, while the English bemoan the general morals of the nation, on the whole they accept their next-door neighbours’ shortcomings. They can’t escape them; so they put up with them.

If you’ve never had to live cheek by jowl with your neighbours, in small, terraced houses with postage-stamp-sized gardens, then you react more aggressively to the tiniest imposition on your rights.

American militia groups of freedom fighters take against state intervention in their private lives that much more ferociously, because they live in the wide-open backwoods of the vast, thinly populated Midwest, West and the South. They just aren’t so used to being imposed upon.

The cramped quality of island life also means that, for all the tolerance shown by the English, they like putting up barriers against any real interference in their private lives. The desire for privacy extends to a lack of interest in anything beyond their small world; a lack of interest intensified by the English happening to speak the world’s most popular language; not much need, then, to learn another.

For all the English absorption of waves of immigrants, there still have been very few invaders in the past 2,000 years, principally because of that island status. Napoleon may have thought the Channel a ‘ditch to be jumped’ but he never did jump it; neither did the Spanish Armada or Hitler. Watery borders are harder to cross than terrestrial ones.

Island status has tended to make England a strong, independent country; one that hasn’t embraced European integration – or the euro – with the enthusiasm of neighbours across the Channel who share a land mass.

But it also makes for a relatively unsophisticated people – afraid of foreign food and languages; happier to speak English and eat fish and chips on Spanish package tours, rather than risk embarrassment, and an upset stomach, by striking out on their own abroad.

Too much emphasis on the uniformity of a single island race risks ignoring the geological differences between different counties.

That connection – between English counties and their supposed idiosyncratic landscapes – struck me on a recent visit to north Holland.

Travelling by train through the flat fields, I was intrigued by how similar those fields were to seventeenth-century Dutch landscapes by Aelbert Cuyp: the fields were carved into rectangles by arrow-straight dykes, with Friesian cows sprawling on their banks.

My train journey took three hours, from Schiphol Airport to Groningen, and the landscape barely seemed to change all the way there – it appeared uniformly Cuyp-like, and stereotypically, almost ludicrously, Dutch.

On the return trip, this time with a Dutchman, he pointed out tiny distinctions between the various landscapes that I hadn’t noticed on the outward leg – differences between the ways the small clumps of willows had been pollarded; how the dykes varied in length and breadth.

People from abroad have said the same of England as I initially said of the Dutch landscape: that it all looks pretty much the same; that the differences between, say, the craggy, bony, mountainous horizons of Cumbria and Kent’s soft, low-slung landscape, with its orchards and oast houses, don’t amount to much. To them, it all looks much-of-a-muchness, in a uniformly English way.

However little we might happen to know about oast houses or the mountains of the Lake District, that strikes us as ridiculous. Most of us have innate attachments to different counties, springing from what strikes us as extreme dissimilarities between them.

We might prefer, say, Dorset’s exposed rural roads to the lanes of Devon, deeply carved into the field margins, diving into clefted combes; we might have robust views of the merits of hilly Gloucestershire over very flat Norfolk.

Perhaps we exaggerate those county differences a little because of our affection for them. It’s not as if individual counties were originally planned according to their geological features; when the Anglo-Saxons carved England up into Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex, East Anglia and Kent, they hardly did it on the basis of what each region looked like.

But, still, there are strong historical, literary and sociological reasons why some counties began to look different over the centuries and developed certain idiosyncratic characteristics, whether you’re an Englishman or a Dutchman. And, in fact, there often happen to be extreme geological differences between the counties. Certain geological features naturally cross county borders but, still, they are more marked in some counties than others.

When it comes to dividing Britain into similar-looking chunks, Sir Halford Mackinder, a leading British geologist in the first half of the twentieth century, made a good general rule.

Draw a line from the mouth of the Tees, in the north-east, down to the mouth of the Exe, in the south-west, and all the main hills and mountains – Highland Britain – will be on the north-west side of the line. The Caledonian earth movements built up the Highlands around 470–430 million years ago.4

To the south-east of Sir Halford Mackinder’s line lies Lowland Britain – the most fertile, and most heavily settled, part of the country, smoothed out during the Ice Age by glaciers, which deposited a rich layer of silt and clay as they melted.

You can trace the beginnings of a north–south divide to those differences in landscape either side of Mackinder’s line. Certainly the Romans tended to build most of their villas on the well-drained, light, lowland soils, on the south-eastern side of the line.

Glacial action levelled the Midlands – ice sheets smoothed away soil and loose rocks, leaving behind a gently undulating rock surface ridged with outcrops of harder stone. The heart of England is really a plain – more grassland than arable – divided by hawthorn and oak hedges. The rolling fields of the West Midlands are formed by sandstone embedded with Upper Carboniferous Coal Measures.

Within that flattish Midlands plain, there are still some geological differences – the plain straddles the soft rocks of the south and east, and the hard rocks of the north and west. So it’s not all flat: in Birmingham, from Selly Oak to Sutton Park, the Bunter Pebble Bed of shales and red sandstones – with layers of cobbles and pebbles deposited by rivers 200 million years ago – produces a varied landscape of steep-sided, thickly wooded valleys, punctuated with heath and gravel.

The Midlands are hemmed in by more dramatic geology. To the north lie the Pennines. To the west, the plain furls up into the Malvern and Abberley Hills and the Wyre Forest. The Armorican movements – so called because they created the rocks of Brittany, also known as Armorica – pushed up the Malverns, the Pennines and the Mendips. They also bent the Coal Measures – Britain’s coal-bearing seams, built up around 360 million years ago – into basins, with a powerful effect on which parts of England would turn industrial in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (see Chapter 10). Armorican granite masses include Land’s End, Bodmin Moor and Dartmoor.

Glaciers carved out much of the Lake District – the scooped-out valleys they formed were scattered with a rough scree of angular stones, melded together to make so-called breccia. The Skiddaw Slates were laid down first, followed by the volcanic rocks that produced the mountains of Langdale Pikes and Helvellyn.

In the later Ice Age, an ice cap developed over the Lake District – the ice spread through the valleys, widening and deepening them. As the ice retreated, it left behind moraines – piles of glacial debris – that blocked the mouths of the valleys and produced the lakes.

Where rivers seeped from under the glaciers, they carried gravel and sand with them, leaving a trail of long ridges and irregular mounds made of these materials – called kettle moraine, it can be seen in Brampton, Cumbria, and the Till Valley, Northumberland.

Outside the Lake District and the Pennines, England may be short on mountains, but it’s long on escarpments – steep-faced hills, formed by differing levels of erosion in sedimentary rocks or faults in the earth’s crust.

Hadrian’s Wall was built on top of a cliff formed by one of these faults: the Whin Sill, a line across the neck of Britain, where magma poured between a pair of tectonic plates to form a 70ft-high sill, on top of which the 20ft wall was built.

Escarpments provide natural ancient roads – like the Ridgeway – and boundaries. Oxfordshire’s border runs along the escarpment of the lower Cotswolds, from Edgehill to Chipping Norton.

They also make for dramatic inland cliffs. If you head south on the A46, from Stroud to Bath, to your left it’s all 170-million-year-old Middle Jurassic limestone, producing a high, stone cliff. To your right, you’ll see a low, flat valley, formed 20 million years earlier by easily eroded Lower Jurassic clay.

This fault line runs from Gloucestershire to Lincolnshire, via Warwickshire, Rutland, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire. The escarpment dictates the use of the land all the way.

Heading north on the A15 through Lincolnshire, to the right there are high, limestone plains, grassy enough to produce good grazing for sheep, and flat enough for RAF airfields during the war. On the left, in the Lower Jurassic valley, the sheltered land is farmed more intensively.

When these beds of rock, gently slanting in the usual south-easterly direction, break or slide, you end up with steep faces – or scarps – facing west, with gentle slopes to the east. These are prominent in the so-called Scarplands of England – stretching from southern Dorset, through the Vale of the White Horse, Northamptonshire, Lincolnshire and up into Yorkshire; like the flat vertical face of Lincoln Cliff, the ridge that runs north–south through central Lincolnshire. The Scarplands include the scarps of the Hambleton and Cleveland Hills, the North Yorkshire Moors and the Cotswolds escarpments formed by Jurassic limestones and sandstones.

The angle of these hills and scarps changes according to the angle at which the beds of stone were laid. If the beds are vertical, with the central, tallest bed aligned with the crest of the hill, then the hill will be fairly symmetrical, with even slopes on either side – like the Hog’s Back in Surrey or the central ridge of the Isle of Wight.

These escarpments lack the high drama of the Alps; English mountains are foothills compared to the Himalayas. The intense settlement and cultivation of most of England for several thousand years has also taken the edge off any surviving drama in the landscape, lending the country a rich, fertile coat that some have called dull, particularly in the south.

‘England – southern England, probably the sleekest landscape in the world,’ George Orwell wrote at the end of Homage to Catalonia (1938), ‘It is difficult when you pass that way, especially when you are peacefully recovering from sea-sickness with the plush cushions of a boat-train carriage under your bum, to believe that anything is really happening anywhere.’

England – particularly southern England – is certainly sleek and comfortable, built on that undramatic, small scale. But it is those qualities that make the effect of our landscape so exceptionally moving. There is a calmness, a lack of flashiness, a restrained look that loses out in grand spectacle terms to the swaggering giant landscapes of the world; but it gains in subtlety, in the pleasure derived from closely observed, understated beauty.

Cheddar Gorge demonstrates the point. In the heart of limestone-rich gorge country – Somerset limestone was easily carved by the meltwaters that came with the end of the Ice Age – the gorge is called England’s Grand Canyon.

It is indeed Britain’s deepest canyon, at 371 feet. But it still has some way to catch up with the real Grand Canyon, in Arizona; 277 miles long, it ranges from four to eighteen miles wide and sinks deeper than a mile, or 6,000 feet. The whole of Britain is only 600 miles long and 200 miles wide.

If I asked you for a stroll one morning along the floor of Cheddar Gorge, following the B3135 near the village of Cheddar in the Mendips in Somerset, we could walk its three-mile length and be back in time for tea. Try walking the Grand Canyon, and you wouldn’t be back for a month.

America big, England small – a crashing cliché, but true nonetheless.

‘The whole conception [of carving presidents’ heads into a cliff-face] really requires the vast American background of prairies and mountain chains,’ said G. K. Chesterton, ‘Anyone would feel, I think, that it would be rather too big for England. It would be rather alarming for the Englishman, returning by boat to Dover, to see that Shakespeare’s Cliff had suddenly turned into Shakespeare.’

There’s a parallel between the small-scale, undramatic English landscape and English art. Alan Ayckbourn, Philip Larkin, Barbara Pym, Kingsley Amis, Alan Bennett, Anita Brookner … they all concern themselves with what you might call little art, with the small things in life, happening in out of the way places.

‘So little, England. Little music, little art. Timid, tasteful, nice. But one loves it, one loves it,’ says Guy Burgess, the spy in exile in Moscow, in Alan Bennett’s 1983 play, An Englishman Abroad.

These modern writers are in a long tradition of little art, related to our island nature, temperate climate, unthreatening landscape and the uneventful, small horizons of English life. Jane Austen wrote of ‘the little bit (two inches wide) of ivory on which I work with so fine a brush’. Thomas Hardy said, ‘It is better for a writer to know a little bit of the world remarkably well than to know a great part of the world remarkably little.’

Still, drama lurks beneath the genteel veneer of Jane Austen’s Bath or Hardy’s Wessex; as it does beneath the sleek, grassy coat of the English landscape. Contrary to what Orwell said, a huge amount has happened here over the last several billion years and, if you look closely, you can work out precisely what.

The best way is to look at the stone that’s been extracted from under that fertile coat, and then used for English buildings: whether it’s the oolitic limestone of Cotswold cottages, the gingerbread-coloured ironstone of Northamptonshire, or the delicately carved tombstones of Somerset, made of Dundry stone, Pennant sandstone and Bath stone.

Most countries have a wide selection of building stone. But it’s the sheer quantity and variety of stones that set England apart; along with the fact that the country is still full of buildings constructed out of local stone.

Before the arrival of the trains, cross-country transport was so limited, and so expensive, that it was easier to quarry building materials from the ground beneath, rather than carry it great distances. The Hospital of St John in Sherborne, Dorset, was built in 1438, using Lias stone from Ham Hill. The quarry was only twelve miles away but, still, the expense of transporting the stone was greater than the cost of the stone itself.5

Even stained glass could be made on the spot, to save on transport costs. Medieval furnaces were built in riverside kilns in woods, producing forest glass from river sand and beech wood ash. In the middle of a remote forest, glaziers could create extremely exotic colours, using metallic oxides like cobalt to produce blue glass, and gold for pink glass.

Dependence on close-at-hand materials means you can spot the exact moment the geology below the ground changes, by examining the buildings above it.

Buildings in east Leicestershire change colour as you move north, from pale limestone to golden-brown Middle Lias marl-stone – called ironstone, because it’s rich in iron oxide. In Lincolnshire, where the Middle Jurassic limestone runs out, the drystone walls above it suddenly give way to hornbeam and blackthorn hedges, threaded through with dog roses.

Above that belt of limestone – an excellent building stone, formed when dinosaurs walked through Lincolnshire – lie the county’s biggest, most beautiful buildings. Lincoln Cathedral even has its own quarry, producing Lincoln Silverbed limestone, a creamy, beige stone, still cut and carved by masons trained in medieval techniques.

In places where there isn’t much building stone, but there was the money to buy and transport it, stone from other parts of the country – and foreign countries, too – was used.

Fifteenth-century Eton College, next door to Windsor, was largely built – thanks to generous endowments – with Caen stone from Normandy, Merstham stone from Surrey, Bath stone, Clipsham limestone from Rutland, Headington limestone, Magnesian limestone from Yorkshire, Kentish Ragstone from Maidstone and Jurassic Taynton stone from the Forest of Wychwood in Oxfordshire. Taynton limestone was also used for All Souls College, Oxford, and Windsor Castle; a brown, large-grained, shelly stone, around 175 million years old, ideal for fine carving.6

The later the building, the more likely it is to use exotic stone, as transport costs decreased over time. Salisbury Cathedral, erected in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, was principally built of local Chilmark limestone, quarried only twelve miles away. St Paul’s Cathedral, built in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, is largely made of Portland limestone from the Isle of Portland, Dorset.

When groups of really old buildings survive, it’s usually because of the quality of the local stone. Most Anglo-Saxon houses, built of timber or clay, with straw roofs, eventually rotted into the ground. The only surviving medieval timber church is in Greensted, Essex; the oldest continuously inhabited, timber-framed house in England is Fyfield Hall, Fyfield, Essex, built in 1150. In the robust stone Norman churches that replaced less substantial Saxon churches, the only Saxon remnant will often be the crypt, concealed beneath the later superstructure.

Extensive Saxon buildings only survive in counties with easy access to durable stone – like St Laurence’s Church, in Bradford on Avon, Wiltshire, built in AD 1000 from the local Jurassic Great Oolite limestone, one of the best English building stones.

If chalk creates the English landscape of legend, then another kind of limestone – Jurassic, oolitic limestone, a sedimentary calcium carbonate stone – creates the legendary English building. A scimitar-shaped sash of this wonderful limestone loops, from north-east to south-west, across England’s torso, from Yorkshire through Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire, Oxfordshire, Wiltshire and Gloucestershire, down to Somerset and Dorset.

The deep brown, cream and Cheddar-yellow stone of Cotswolds villages and Oxford colleges is Jurassic, oolitic limestone, cut with limonite, an iron mineral; the more iron in it, the deeper the honey-yellows and the browns. Where that oolitic limestone peters out in the west, in a line of escarpments falling to the Severn Vale, the picturesque golden cottages – and the Japanese tourists tracking their course – begin to disappear.

Those Cotswold cottages also draw their quintessential Englishness from their mottled, lichened, crooked roofs – made from Stonesfield slate, or pendle, as they call it in the Oxfordshire quarries. Stonesfield is strictly a limestone, not a slate, but it splits naturally to give the appearance of slate. Where other slates split along geological fault lines, the pendle is split by the moisture – or quarry sap – trapped within. Medieval masons used to leave the slate stone outside over the winter and clamp it, so that, when the frost came, the stone split into slates.

A similar splitting technique was used on Collyweston stone slate – also really a limestone, not strictly a slate. Quarried in Northamptonshire, between Deene and Stamford, Collyweston slates often cover the roofs of Cambridge colleges. In Lancashire, heavy, dark Carboniferous sandstone slates, known as flagstones, were used for roofs; it helped that the sandstone was immune to disintegration from smoke and soot in the industrial north.

Part formed from animal skeletons, Collyweston stone is rich in fossilized mammals and lizards. Oolitic limestone, part formed from the shells of sea creatures, is flecked with fossilized fish scales and teeth, often visible to the naked eye. All British limestone is formed by fossilized marine organisms, apart from an Isle of Wight limestone, used for much of Winchester Cathedral; it’s the only limestone formed by freshwater organisms.

Ammonites, too – those round fossils, shaped like looped snakes – are the remnants of Jurassic and Cretaceous molluscs. They’re often found in Dorset, particularly on the Isle of Portland, where they are incorporated into walls.

Northamptonshire lies on a ridge of oolitic Barnack limestone, the best building stone in the country, used to finish the battlements and pinnacles of England’s newest cathedral, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, in 2000. Some of the biggest, stone-hungry buildings of Norman England were built on the Barnack limestone ridge, near Barnack village. The pitted moonscape of the nearby quarry is now known as ‘hills and holes’, produced by centuries of digging. From the Saxon period onwards, Barnack stone was sent downriver to Peterborough, then on to Ely, Bury and Cambridge, to build many of the churches in East Anglia.

Limestone country tends to be spire country, too. Stone-rich Northamptonshire has 200 medieval churches and around eighty spires. It’s been called the county of squires and spires; William Camden, the late-sixteenth-century antiquarian, said it was ‘passing well furnish’d with noblemen’s and gentlemen’s houses’, and it is still largely divided into ancient estates.

Wherever you have limestone, you get limewash, too: lime slaked in water, producing a breathable whitewash layer for cottages across the country. The distinctive strawberry ice-cream pink of East Anglian cottages was made by adding a dash of oxblood to the mix. The pinkish look was often further stylized with pargeting – combing the wet plaster into decorative patterns.

Most of England’s cities derived their character from local stones, bricks or timber, before the 1950s takeover by concrete, glass and steel. Bristol is principally grey, because of the Pennant sandstone quarried to the east of the city; although Pennant blushes plum and chocolate brown, too. Bath is pale gold, thanks to Bath stone, an oolitic limestone originally quarried at Combe Down, a mile and a half south of Bath city centre.

Because of the extreme variety of English stones, towns, which are otherwise very similar, feel completely different because of the stones beneath.

Cambridge, with limited medieval access to building stone, was originally largely built of clunch (a type of hard chalk) and brick, before better stone was imported. Chalk, for all its beautifying effect on the English landscape, is not a good building stone, ending up dirty and pock-marked; the chalk churches of Hertfordshire are often now pebbledashed or rendered with cement as a result.

England’s other archetypal university town, Oxford, is only sixty-seven miles from Cambridge. In most sociological respects, the towns are as similar as can be. But Oxford looks, and feels, different because it happens to be on the oolitic limestone belt, and so has always been a town built of handsome stone. It’s partly because of that honey-coloured stone that Oxford gets the monopoly on romantic university stories: whether they’re about dreaming spires, teddy-bear-carrying sons of marquesses or opera-loving detectives investigating murder sprees in senior common rooms.

In the same way that geological characteristics cross county boundaries, a single county can encompass a huge variety of rocks.

Berkshire, for example, is a mixture of extremely different geological landscapes. Around Bagshot Heath, it’s all pines and sandy heath, covered with heather and gorse. Rural Berkshire, in the west of the county, rests on the chalk landscape of the Downs. Commercial, commuters’ Berkshire lies to the east, on the flat, featureless landscape near Reading, formed by the London clay of the Reading Beds.

Some counties, though, are defined by a single stone, like Cornwall, a county of granite – formed, like other igneous rocks, such as gneiss and basalt, by volcanoes. The county’s granite buildings outnumber those in the other granite counties – Cumbria, Devon and Leicestershire – combined. Cornwall’s rugged, robust, ancient feel has a lot to do with the ultra-hard, long-suffering stone that underpins much of the peninsula.

The coarse-grained, grey and silver-grey stone is so difficult to carve that the mouldings on Cornish churches are necessarily simple. For the same reason, Cornish church towers – like those at St Levan and St Buryan – tend to be chunky piles of enormous stone blocks; the bigger the block, the less carving is needed.

Granite is so hard-wearing – and so hard to carve – that individual, untouched stones were used for walls, cattle troughs, gate-posts and even bridges. And it’s so heavy that, on some Cornish barns and cottages, no mortar is needed to hold the granite blocks together.

Much of the farmland at Land’s End is divided by Bronze Age banks made up of ‘grounders’ – enormous granite boulders which rolled down from the moors in the glacial period. Often they’re so hard to move that the banks have swerved in order to incorporate them.

Look under a Cornish hedge, and you might well see a moorstone – a granite stone taken from the hills and moors as a foundation for the hedge. A hefty moorstone might not be as sophisticated as the drystone walls of the north, but few things are stronger or more watertight.

Pelastine granite from Penryn was used for Tower Bridge; and De Lank granite from Bodmin Moor for the wave-blasted Eddystone Lighthouse off the Devon coast.

Four previous lighthouses were built on the Eddystone Rocks before the current lighthouse was erected in 1882. The first was too small, the second destroyed by a storm, the third by fire and the fourth undermined by waves. The current incarnation has lasted 130 years, thanks to its 2,171 pale-grey, granite blocks, each block dovetailed with other blocks on five of its six faces.

Granite also produced the island of Lundy, the solid foundations for St Austell, Bodmin, Land’s End, Carnmenellis, Camborne–Redruth and the outcrop on which Dartmoor sits. The weathered granite tors of Dartmoor were left behind when the soils and softer stones around were worn away. The same effect produced the Scilly Isles: granite chunks which remained above water once the sedimentary rock had been eroded by the waves.

The ancient standing stones of Berkshire were formed by a similar process. Berkshire sarsens – large sandstone boulders – were left lying on the earth after the surrounding earth had been weathered away. Sarsens like this were then used in building the chambered barrow at Wayland’s Smithy, Ashbury, and, later, that at Windsor Castle.

By plotting the position of these barrows, you can still see where early Bronze Age settlements, from 1650 to 1400 BC, flourished in England.

The Bronze Age heartland of south Wiltshire and Dorset is rich in barrows. They’re found, too, in Berkshire, the northern border of Bronze Age Wessex. Some later Bronze Age fields still survive on the Berkshire Downs; and there are still plenty of Iron Age lynchets – cultivated hillside terraces – across England, particularly on chalk downs. Plough a Berkshire field and you might cut through 4,000 years of history.

It isn’t all unrelenting granite in Cornwall. The huge slate quarry at Delabole was begun before 1600 and reached a peak in the nineteenth century, producing a vast 400ft-deep hole, a mile in circumference. Cornish slate roofs – in brown and fawn, as well as grey – combine harmoniously with granite, with the largest slates at the eaves, the smallest next to the ridge, giving the illusion of greater depth. Slate-hung walls were popular in Cornwall, too, particularly in the early nineteenth century, as they were in Devon and the Lake District.

Until canals allowed the easy, cross-country transport of cheaper, lighter Welsh slate in the late eighteenth century, slate-rich counties used their own slates: like the lovely green and blue-grey Swithland slate of Leicestershire, dotted with lichen and moss. Swithland slate was also used for gravestones, doorsteps, plinths, window sills, gate posts, cheese presses, chimney pieces, salting troughs and milestones.

The only problem was its weight; unlike light Welsh slate, it could slowly crush any building it covered, and so fell into disuse. Today, in Swithland Wood, the old slate quarry is a gaping crater, 190 feet deep, filled with water.

Cornwall’s hard, rocky, granite profile is intensified by the absence of trees, blasted by south-westerly winds that whip in straight off the Atlantic. The higher you go in Devon and Cornwall – climbing up to the moorlands of Dartmoor, Bodmin Moor and Exmoor – the more blasted you are by the wind, and the fewer trees there are. Above 2,000 feet, Dartmoor has probably always been treeless.7

Until the sixteenth century, much of England was pretty well wooded, but not Cornwall – which has always been short of trees; and so it’s been short on half-timbered cottages, too.

The Cornish often built in cob, or clob, instead – two parts mud and chopped straw, one part shilf, or shards of waste slate. Cob is laid on stone or pebble plinths, painted with cream or pink limewash, and usually roofed with thatch, because cob can’t support a slate or tiled roof. Different counties used different cob recipes: the clay cottages in the New Forest are strengthened with heather; Milton Abbas, Dorset, is largely built of chalk and clay cob.

Where the stone ran out, or was inaccessible, people turned to other materials. In Leicestershire, the stone is often hidden beneath 150 feet of boulder clay, meaning the inhabitants resorted to building mud houses. John Evelyn wrote of Leicestershire in 1654, ‘Most of the rural parishes are but of mud, the people living as wretchedly as in the most impoverished parts of France.’ Several mud houses, laid on a waterproof stone platform, survive in Leicestershire; there are hundreds in Devon.

The extreme variety of English stones gives counties a distinctive look. And the ease of carving of many of those stones, and the fertility of the soils, means much of England was settled, in substantial stone-built developments, at an early stage.

Sometimes, though, unsuitable geology made early human existence unbearably bleak, leading to a lack of ancient settlements. The great stretches of Oxford clay in Bedfordshire and Huntingdonshire were barely colonized by the Romans – the less than ideal soil was also covered with thick forest – except along the more heavily settled Ouse valleys and gravel terraces.

Charnwood Forest, Leicestershire, was largely uninhabited until the early nineteenth century, because it grew on top of a geological freak: ancient pre-Cambrian volcanic rocks – syenite and diorite – that were extremely hard to cut into. Any pre-Victorian cottages in the forest are necessarily timber-framed because of the lack of building stone. Thanks to the inhospitable geology, this barren, hedgeless wasteland wasn’t enclosed until 1829.

Where easily harvested stone wasn’t available, locals turned to timber for building material. Much of early medieval England was thickly wooded – thus the predominance of timber vaults in churches from York Minster to St Albans Cathedral; a legacy, too, of the English skill at ship-building. In France, stone vaults predominated.

The desperate stripping of England’s woods for construction, as well as heating, started early. North Norfolk was pretty much bare by the time the Domesday Book was written in 1086. Like much of the rest of England, where there wasn’t much stone or timber, Norfolk turned to bricks. By 1650, the King’s Lynn Corporation was paying 14 pence a foot for oak; and only 13 shillings a thousand for bricks. King’s Lynn became a brick town.

Heavy use of brick – particularly exposed brick – is a deeply English characteristic, symptomatic of our preference for the homespun, domestic look over the imposing, grand scale. It helps that brick is that much cheaper than stone. Brick is also expressly English, rather than Scottish: the long brick terraces of Manchester and Liverpool give way, over the border, to the sandstone of Glasgow and the granite of Aberdeen.

The world’s biggest consumers of bricks per capita, after Britain, are Kentucky, Tennessee and Alabama – continuing the long Southern tradition of robust Anglophilia. When they build an out-of-town shopping centre in the Deep South, more likely than not, it’s in neo-Georgian, brick style, recalling the Old Country.

Even our modernist buildings – like Tate Modern, formerly Bankside Power Station, the stripped-down, sleek, futurist building, built by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott from 1947 to 1963 – are made of brick. Industrial buildings also used bricks heavily. Stanley Dock, Liverpool, constructed in 1900 with 27 million bricks, is the biggest brick building in the world.

In other countries, the outer brick walls of modernist and industrial buildings are plastered, smoothed over and whitewashed – to tackle a more powerful sun, as well as to produce a cleaner, more even, minimalist, monochrome look.

Continental Europeans mocked our mass-built, modernist houses in the 1930s for the homespun use of brick, particularly when combined with our addiction to historical styles. Our inter-war buildings may have been new, but they were neo-Dutch, neo-Swedish or neo-Tudor, and only rarely neo-neo: that is, utterly original, and embracing the future as opposed to the past.

The English devotion to brick is a relatively recent phenomenon. Between the departure of the Romans from Britain in AD 410 and the first surviving, home-made brick at Little Coggeshall Abbey, Essex, in around 1225, the English lost the art of brick-making.

For 800 years, they could only reuse old Roman bricks. Since then, the English have perfected the art, although they did make some pretty hideous bricks along the way, including the screaming red bricks from Accrington, known as ‘Accrington bloods’, made from the local shales in the Lancashire Coal Measures.

After the Great Fire of London, the new terraces were largely built in brick – often distinctive, yellow-brown, London stock brick, made with local clay, much of it from Kent and Essex. It made sense to manufacture bricks locally; because they were so heavy, they were expensive to move. Until as late as the Second World War, bricks were rarely transported more than thirty miles from the brickfields where they were manufactured. Brickfields – dangerous, unhealthy places to work – scarred the landscape across the country deep into the nineteenth century.

The dimensions of those bricks were price sensitive. In 1784, a Brick Tax was levied on every thousand bricks, irrespective of size; and so brick dimensions began to grow. Tudor bricks are, on average, 9 inches by 4½ inches by 2¼ inches. Georgian bricks – a ¼ inch thicker than Tudor ones before 1784 – got 3 inches thicker after the tax was introduced.

Machine production made those dimensions more precise. By the end of the nineteenth century, yellow stock brick gave way to machine-made red bricks, their edges so even that the mortar joints were reduced to less than a third of an inch thick.

Kent – handy for brick-making specialists from northern Europe – has the best brickwork in England. Those foreign specialists introduced Flemish bond – a style of laying bricks, head first (‘headers’), then lengthways (‘stretchers’), in a single ‘course’, or row. Before then, English bond – alternate rows, each entirely made up of headers or stretchers – had been popular. Flemish bond dominated English bricklaying from the 1630s until the nineteenth century.

Kent’s proximity to northern Europe also meant Dutch gables were popular, particularly in Thanet, Hythe, Worth and Ash; as were big, orange Dutch roof pantiles, introduced to England as ballast on cargo ships in the seventeenth century. These were mostly replaced by local tiles in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Kent tiles were made from Wealden clay, studded with Paludina limestones, largely consisting of snail and other mollusc shells.

The tiles were often laid on long, swooping roofs, called catslides, dropping down almost to the ground (catslide roofs could also be thatched). Or they were hung vertically to protect the walls. When Kent tiles were polished, they produced so-called Bethersden marble, found on elaborate tombs at Chilham and Woodchurch churches.

Thatched roofs were popular in counties where the right sort of clay for tiles was in short supply, like Suffolk, which has a higher percentage of thatched roofs than any other county. In Norfolk, wheat, field straw and Norfolk reed from the Broads were used for thatching, although plenty of thatched roofs were later replaced with tiles.

For all the English variety in building stones, we are short on marbles and exotically coloured stones. An exception is Blue John, the purple, blue and yellow crystallized fluorite found only at Treak Cliff Hill, in Castleton, Derbyshire; it’s often seen in grand Derbyshire houses, including on the chimney pieces at Kedleston Hall and for a vase at Chatsworth.

Orwell’s misguided point about the sleekness and dullness of the English landscape could be applied to its stones. There is a great variety of English stones, but few have the dramatic colours of the best Italian marble or the white purity of Carrara marble, used to build the Pantheon, Trajan’s Column, Siena’s Duomo and Marble Arch.

England’s stones may not be much good at producing splashes and streaks of lurid colour; but they do produce a quiet, understated strain of beauty, in harmony with the landscape they were extracted from.

The best English buildings – particularly medieval ones, of thickly lichened limestone – may not be dazzling, polychromatic jewels, but they are no worse for that. They blend into the landscape, rather than standing wholly apart from it. They appear to grow out of the earth they’re rooted in; like the fifteenth-century Knole House, Kent, the childhood home of Vita Sackville-West, who said of the house, ‘It has the tone of England; it melts into the green of the garden turf, into the tawnier green of the park beyond, into the blue of the pale English sky.’