Metaphysical Taoism, or ontological Taoism for some, is known to us today through the book of divination, called the I Ching,1 and the theory of acupuncture. To introduce these domains, I will discuss three terms that are often used by Chinese authors:

This model served as a reference point around which Chinese culture has woven thousands of variations.

Confucianism is the art of living for a civil servant. Imperial China was an extremely structured country, with an important and powerful administration at the service of the emperor, capable of representing the central administration throughout the immense territory of the country. Confucianism is the theory that organizes the principles of the imperial administration, one that remains a model of strict and precise social organization. It freely incorporates elements of Taoism, and then of Buddhism when it arrived in China around AD 200. It situates the social hierarchy in the order of the world and the individual in the social order. This movement was founded by Confucius (c. 551–497 BC) and Mencius (c. 380–289 BC) in the same era as the first Taoists.3 A way to summarize Confucianism is to conceptualize the universe as a piece of furniture in which everything has its own drawer. There is the world, the Chinese empire, the regions, the towns, the individuals, and the organs. The details of this first systemic vision of the world are found in the I Ching. This is a book of divination that is also the first manual that proposes a formal language4 capable of describing the systemic dynamics of all phenomena and their capacity to change. Confucianism, like other Chinese schools of thought, not only utilized the I Ching but also contributed to its elaboration. Certain commentaries on the I Ching are attributed to Confucius.

According to the I Ching, all that exists is a system. Each system can pass through sixty-four states. Each of these states is a particular balance of yin and yang forces. In certain circumstances, each state can transform itself and become another state. The universe is a system that contains subsystems like the planets and the living creatures. The universe does not function like an organism, but it is organized by the same principles. The universe, the society, the individual, and the organs are bound to take up the sixty-four states described by the I Ching.

I will not attempt to summarize this system, but I would like to highlight certain characteristics of the I Ching that can be found in most Chinese approaches to the body. The states described by the I Ching are represented by the symbols called hexagrams. These symbols are generated by the combination of six lines that can be either yin or yang. These combinations make up the sixty-four systems. A basic rule is to analyze hexagrams by going from bottom to top. This practice can be related to the Chinese practice of reading a body from the feet to the head, from the anchor points to fine motor skills.

An example of how to use the I Ching when one analyzes the behavior of a person. One of the hexagrams describes how a system can influence another system.5 In a passage dedicated to this system, the authors of the I Ching take as an example a marriage proposal. They discuss two extreme situations:

1. The feelings of love are so deep that they are activated in the feet. From there they rise in the direction of the face and the voice. These feelings are deeply felt but are not always capable of finding an adequate expression.

2. Love that expresses itself through the jaw, cheeks, and tongue is “the most superficial way of trying to influence others.” “The influence produced by mere tongue wagging must necessarily remain insignificant.” (Wilhelm 1924, p. 125)

This example introduces a metaphor that is regularly mentioned by body psychotherapists:

In these two cases, the mind depends on mechanisms that distribute themselves throughout the organism. We also find this perspective in the philosophical writings of the Taoists: “The True Man breathes with his heels; the mass of men breathe with their throats. Crushed and bound down, they gasp out their words as though they were retching” (Chuang Tzu, 1968, IV, p. 78).

When one uses such a theoretical frame, one can easily conceive that a hand gesture can, at the same time, participate in a fine equilibrium of the body in the gravity field, express a thought (it is springtime), betray a feeling (I am anxious), handle an object (to pass a cup of tea in a particular manner), and communicate something quite explicit (encourage a father to accept my marriage proposal to his daughter). This state may create another. Perhaps the fiancé is overly respectful (his feet are immobilized) and the father feels ill at ease and distant. Most hexagrams are associated with a metaphor linked to the movements of the elements. Here, it is the one of the sun distancing itself from the mountain. If the fiancé has an overly easygoing attitude, the father may not want to welcome someone who irritates him (like water on fire) into the family.

Many specialists in bodywork know the I Ching well because it is a formalized way that can be used to understand and describe certain observable complex dynamics used by organisms. An example of the intellectual comfort offered by the dialectical system of the I Ching is the following:

Walking analyzed using the principles of the I Ching. Every extreme state (whether yin or yang) is considered unstable. The stability of a system demands a blend of yin and yang energies. If I am standing with all of my weight (a yang function) on my right foot, my left foot carries no weight (a yin function). This absolutely unbalanced distribution of yin and yang on my feet makes for an unstable posture. A more stable manner to stand up is to distribute my weight equally on both feet. There will therefore be an equal amount of yin and yang in each foot. This position is totally static. If I want to walk, I will shift the yang from one foot to the other while the yin distributes itself in a complementary fashion. The distribution of my body weight changes in such a rhythm that it permits me to move about. There is then in place a stable activity that establishes a balance between the feet that alternatively become yin and yang.

This type of discussion concerning the dynamics of the body can be found in the majority of the Chinese and Japanese martial arts.

Acupuncture is a second group of practices and theories that illustrate how Taoist metaphysics can be used. It is one of the main branches of Chinese medicine. The theory of acupuncture is close to that of the I Ching, but it develops themes that are born out of a detailed exploration of the dynamics of chi.

A way to situate the particular alternatives of Chinese medicine is to contrast its origins with those of the medicine of the ancient Egyptians.7 The Egyptians and Chinese of old felt an immense respect for their dead. However, this respect expressed itself in opposite ways that lead to two different types of medicine.

The Egyptians embalmed the cadaver so that it might protect the soul of the deceased and buried it near the family home (in a pyramid if the deceased were a pharaoh). To accomplish that, they developed an immense surgical and physiological competence that allowed them to preserve the body for thousands of years. The art of embalming seems to have been particularly developed between c. 1738 and 1102 BC. This is how the Egyptians established one of the bases of allopathic medicine that is characterized in this discussion by the necessity to penetrate the body to gain understanding and provide treatment. The traditional Chinese belief is that an individual’s body belongs to the family. Therefore, the body must be delivered intact to the family before its incineration. That is why the eunuchs of the imperial court preserved and kept their sexual organs in formalin, so that these could be burned with the rest of the body at the end of their life. The Chinese were thus horrified by any attempt to dissect a body, dead or alive. Their physicians also believed that an organ lost what characterized it on dying, and consequently, they would learn very little by dissecting a cadaver.

In the nineteenth century, European colonial powers and the United States were occupying some of the main cities of China. Their power was terrifying, their rule sometimes cruel. Their allopathic medicine was a standard-bearer of their civilizing mission. For the Europeans, “scientific” medicine was the only valid approach to cure disease. They constructed schools of medicine and asked the Chinese government for cadavers for their courses on anatomy. The Chinese authorities did not dare ignore what was presented to them as a requirement. At the same time, these authorities could not authorize the dissection of Chinese citizens. The compromise was to send to the European medical schools the cadavers of criminals put to death as soon as the executioner had severed their head. This solution posed a problem for the professors of anatomy when they wanted to teach the anatomy of the neck, for it had been damaged by the ax used for the execution. They wanted, for courses on head and neck anatomy, to receive the cadavers of individuals who had been killed in other ways. The Chinese authorities proposed sending those who were condemned to death to the medical schools, so that the physicians could kill them any way they wanted.8

In spite of their fear of dissection, the Chinese nonetheless possessed important knowledge about the body. Chinese physicians could observe cadavers on the battlefield or accompany the executioner during torture sessions. They would ask the executioner to torture the part of the body they wanted to study and documented it. The advantage was to be able to observe a living anatomy.9 On the battlefield, Chinese physicians measured the length of the principal blood vessels. In the torture chambers, they studied the circulation of the blood in the organs 2,000 years before European physicians. Having said this, Chinese anatomy leaves a lot to be desired. The Taoist Zhao Bichen (1933) published anatomical drawings based on what can be known by touching and through meditation. Even if it was influenced by the anatomy charts produced by Western medical schools, this anatomy is not precise and is simplistic. One of the reasons this book is interesting is that it shows the limits of introspection to explore anatomy, even when it is used by great masters of meditation.

The cult of the ancestors is a foundation of Chinese culture. It explains the enormous investment in nonsurgical therapeutic methods, and consequently the institutional efforts dedicated to the development of therapeutic methods using massage, movement, and medication. This effort opened up to the therapeutic approach that is acupuncture. Like the I Ching, this method has only recently integrated scientific procedures, but its principles are explicit and intelligible, and therefore teachable.

Before the arrival of Buddhism, chi was conceived as a sort of undifferentiated matter that serves as the basis for all other matter.10 The idea is close to the one of stem cells that can transform themselves into any other kind of particular tissue (bone, blood, nerves, etc.). Chi is the prime matter of the universe, undifferentiated but rich, that transforms itself and particularizes itself as it differentiates itself. For the Chinese, matter is dynamic. It transforms itself and contains the forces that render it dynamic. The yin characterizes one type of force, a particular type of dynamic.

Chinese theories on the relationship between chi and Tao varied. For certain schools of acupuncture, chi is a derivative of the Tao; for others, it is a sort of twin of Tao, and the Tao is not even mentioned. Chi and Tao are not phenomena that the senses can detect. A wise person can only observe what modifies itself on the surface of things and then deduce, from these observations, what forces such as the chi are being activated. Hot and cold, heavy and light, bright and dark, mobile and static, solid and liquid, and so on, allow us to know if it is the aspect of yang or yin that is at play. In other words, chi particularizes itself in creating a particular material dynamic whose contour and properties it is possible to identify.

Some dynamics of chi pass through the meridians, sort of arteries and veins of the chi. As the blood is just one of the fluids of the body, the chi that circulates in the meridians is but one part of the chi of the organism.

Acupuncture assembles a large number of interesting methods. The basic method consists in exciting specific points situated on the surface of the body, in or on the skin, with needles, moxibustion, massage, and movement.11 These interventions often have a remarkable power to influence the deep physiological dynamics of the human organism. Legend contends that acupuncture was discovered by a hunter, accidentally wounded by an arrow. It had penetrated the external face of the foot behind the ankle. When the arrow was removed, the hunter began to dance and exhibited a strange and joyous behavior. He explained to those who were providing care that he had been suffering for some days from a sharp pain that extended from his kidneys to his feet. He was saying to himself that the arrow must be magical because the pain had suddenly disappeared. A physician, witness to these events, would have subsequently stuck an arrow in the same place on persons who were complaining of a similar pain and thereby cured them.12 Analogous legends allow us to suppose that others found, by trial and error, various “miraculous” points that they pierced with needles, with the intent to intervene in the least painful way possible. They discovered that various ways to stimulate a point could have different effects. Sometimes applying pressure with a finger sufficed; sometimes turning the needle one way had one effect and turning it another way had another effect (yin for left or yang for right). It would seem that Chinese physicians noticed that the points organized themselves in the form of lines, which are the meridians. Each line could be associated to a group of particular set of psychophysiological dynamics and the circulation of chi in the body. The acupuncture points are thus handled as if they were like doors that can regulate the flow of the chi in a meridian, like the valves in the veins of the legs.

According to George Soulié de Morant,13 we find a therapy using 120 points around the year 500; but it wasn’t until 1027 that a physician made a statue showing all of the known points, and 1102 until we had a definite chart relating the points to organs: something established after a particularly systematic research on prisoners condemned to death (pierced with needles before death and then dissected). This medicine “of the points” established correlations between the state of the inner organs and the cutaneous sensations (hot/cold, irritation/comfort, red/pale, etc.). A clinical teaching method based on such observations was developed over more than a thousand years. Every meridian is associated with a yin or a yang value, to an organ, and sometimes to affects. The meridian of the liver is associated with certain headaches and anger, whereas the meridian of the kidneys is associated to clammy and cold hands and fear.

Chinese massage techniques are extremely varied. In the courses given by Hiroshi Nozaki in Lausanne, I learned to massage with fingers, hands, elbows, head, and feet and by walking on the back. Some massages are gentle, and some are painful. We massaged the muscles, the bones, the skin, the organs, the acupuncture points, the scalp, and sometime the space surrounding the body. Some massages follow the theory of acupuncture14 and require a solid understanding of the points and the meridians.

A Chinese masseur only rarely works directly with the emotions that express themselves during a session. If an individual begins to cry, to let sexual movements occur, or to erupt in anger, the therapist typically places a blanket on the person and waits for the crisis to subside by itself. These affects are known and included in the clinical teachings of acupuncture. Often in China, a physician treats several patients at the same time. He moves from one to another, adjusting the needles of one and massaging another. Once a patient’s emotional outburst has subsided, the therapist talks with the patient while he is preparing to leave, sometimes discussing recent events that might be related to the emotional experience. It can happen that at the following session, the physician focuses on the points associated with the emotions previously expressed, but the emotional content is not verbally discussed. There is thus no psychotherapy born out of acupuncture. We are here manifestly in the treatment system of the mechanisms of organismic regulation. The mind is part of these mechanisms without being the center.

Imperial China is without doubt the first lay state in the world. Classically, the historians distinguish a philosophical Taoism and Confucianism born around 500 BC and more religious versions that developed during the Middle Ages under the conjoint influence of Buddhism and Christianity.15 For body psychotherapists, frequenting the philosophical Taoism of Lao Tzu (c. 570–490 BC), ChuangTzu (c. 370–301 BC), and Lie Tzu (c. 400 BC) is often perceived as useful.16 It is not certain that these personages ever existed or that they are the only authors of the books attributed to them, but these writings remain classics in the history of human thought. Two themes developed by this philosophical movement remain relevant for today’s psychotherapists:

The choice of these themes does not imply that they consist of the essential of what Taoism has to teach, only that these are Taoist themes that contribute to some of the discussions in this textbook.

I have heard of letting the world be, of leaving it alone; I have never heard of governing the world. You let it be for fear of corrupting the inborn nature of the world; you leave it alone for fear of distracting the Virtue of the world. You let it be for fear of corrupting the inborn nature of the world; you leave it alone for fear of distracting the Virtue of the world. If the nature of the world is corrupted, if the Virtue of the world is not distracted, why should there be any governing of the world? (ChuangTzu, 1968, XI, p. 114)

Philosophical Taoism may have begun as a movement for retired functionaries, who had been followers of Confucianism while they were working for the state.17 Because their retirement pay is low, they want to learn to live as serenely as possible in such conditions. They think this is feasible only if they acquire a better ability to listen to the dynamics of nature that course through them. The Taoist helps nature help him because he supposes that nature has a restorative energy often inhibited by an attitude that prefers to accommodate to the current mores rather than to nature. Humans are not capable of comprehending or voluntarily mastering this restorative power. But an individual can benefit from it if his attitude and his way of acting create a space within him to permit these forces to express themselves more freely: by meditating, for example. This is the famous “let be” or “let go” of the Taoists that oppose the more voluntary initiatives of yoga.

To create this space in which nature can express itself for the good of the individual, the Taoist elaborated a practice of awareness that permitted him to forge an alliance with the energies that enliven him but that he cannot comprehend. The theoretical frame of philosophical Taoism is minimalist but sufficiently powerful to combat the propensity of consciousness to want to understand and master everything. It consists in learning how to perceive as precisely as possible without interfering. The Taoist sage actively listens to ever-changing atmospheres produced by his organism and his environment like someone who listens to music without telling the musicians how they should play. Once the mind of a Taoist has established a lasting and constructive form of contact between consciousness and the dynamics of chi in the organism, it can finally make informed decisions and use its will to influence the dynamics it perceives with tact. Such voluntary actions are applied in interaction with what is being influenced. The aim is synergic improvement, not an attempt to impose a theory, a desire, or the opinion of others.

The psychotherapist who reads this probably immediately grasps how this way of conceptualizing the dynamics of consciousness can enrich models like Freud’s free association proposed in 1912. “He [the doctor] should withhold all conscious influences from his capacity to attend, and give himself over completely to his ‘unconscious memory’” (Freud, 1912a, pp. 111–112). The psychoanalyst lets himself be permeated by what is going on. The nonconscious regulation systems of the therapist thus have the time to integrate the complexities of the regulatory systems that develop between the therapist and the patient. The flow of conscious thoughts and impressions that inevitably emerge within the therapist can thus stabilize around an emerging theme, which he can explore when he has the impression that it may help him understand the patient. This “letting go” is not a spontaneous property of the mind. It gradually develops by constantly listening to what happens when explicit thoughts interact with implicit impressions. These implicit impressions allow explicit thinking to contact atmospheres that float in the organism and in the space that surrounds the therapist and the patient. We are much closer to the apprenticeship of a musician who sharpens his ear and his virtuosity through practice than to what can be acquired by rigidly applying a set of rules. These Taoists live in nature, are supported by nature, respect nature, and integrate themselves in nature.18 From the point of view of a Taoist, an individual may learn to know oneself better, but he will never be able to comprehend how he functions.

Gradually, awareness and the rest of the organism learn to interact with each other. The Taoist learns to tame brute willfulness, which can often become so violent that it tends to destroy everything the moment it penetrates the subtleties of the being.

The same principle applies for the rapport between willfulness and nature. This attitude is well summarized by the following metaphor.

Vignette on how consciousness relates to nature. The image is that of a boat captain who is traveling on one of the great rivers that nourish the Chinese countryside. The advice is as follows: if the captain thinks he can change the course of the river on which he is navigating, he risks becoming a victim of the whirlpools and currents of the river. If he learns to pilot his boat only as well as is possible, he will know when it is time to draw alongside of or to bypass a reef19

One of the great contributions of philosophical Taoism for the techniques of body psychotherapy is to have made explicit a way to ally consciousness and body reactions without one drowning the other. By stepping away from the world, the wise one does not cut himself off from what is going on in society. Instead, he creates for himself an environment sufficiently simple that his project becomes possible. In the little tales that make up the writings of Chuang Tzu and of Lie Tzu, the wise persons are often consulted by “powerful people.” The dialogue between a retired person and social life is thus maintained.

The Taoist is as wary of the directives given by the emotions as those given by rationalizations. Nevertheless, his search for moderation never leads to the repression of the spontaneous reactions of the organism. The wise person could have “fragile bones and weak muscles,” and have his penis erect “so full is his vitality,” without necessarily being with a woman or trying to intensify his vitality with stimulating exercises.20 If he avoids women, it is because he is in a process of energy conservation. He does not want to waste his aging resources by distributing them to others. To lose his semen wastes what the body contains. I suppose that the Taoist also avoids masturbation. Conforming to the mores of the time, this discourse addresses itself only to men.

The breathing exercises of the philosophical Taoists are only known through indirect sources. I am not aware of works showing how these exercises were practiced before the arrival of Buddhism,21 but the majority of them were taken up by Chi-Kong, in a similar spirit. In these techniques, each movement is associated with a precise respiratory schema to appropriately mobilize the chi and the meridians. Chinese teachers generally avoid teaching how to breathe until the student has learned the movements. The learning of the movements already mobilizes a spontaneous respiration, one that accommodates to the movements without any conscious or voluntary intervention. Thus, the association between movements and breathing occurs at the level of the reflexes and the habits. Only later does the student learn the usefulness of harmonizing respiration and gesture in a more explicit manner. This pedagogy protects students from the damage that the will can do to the deep muscles of respiration.

The student begins by listening to his breathing following a teaching system close to the one already described in the sections on pranayama. He observes whether he is breathing from the abdomen or from the chest. He is asked not to change anything if he notices that his respiration does not correspond to his personal theories about respiration. Spontaneous respiration follows rules that reason does not know. The student is asked to explore his breathing, to become acquainted with it—for example, to evaluate, by counting, whether he breathes in longer than he breathes out, how long each apnea lasts, and so on.

While learning to analyze his breathing and the impact each phase has on the organism, a person realizes that the very act of observation modifies the spontaneous respiration. That must also be observed. Slowly, a student discovers that when his awareness focuses on his breathing, he contacts deep layers of his psyche. By repeating such forms of exploration, he notices how his respiration changes as a function of the seasons, of his inner well-being, or of an illness.

Push far enough towards the Void,

Hold fast enough to Quietness,

And of the ten thousand things none but can be worked on by you.

(Lao Tzu, 1949, XVI)

As the first writings about yoga recommended, this gradual contact with the dynamics of chi is to learn how to make contact with self in a gentle, kind, and tolerant way. If a person does not gradually acquire a softer form of awareness, this type of approach should be left aside. I have already mentioned that the more fragile parts of a person should be protected from anxious forms of psychic intrusion.

To slow down the aging process, the first Taoists took good care of their bodies, and probably made use of acupuncture. The fundamentals of aging wisely consist of conserving, for as long as possible, a large postural and respiratory repertoire. They also cultivated intelligence and memory to preserve the agility of their spirit. This search for longevity drove them to become obsessed about their health and their physique. Health care was not as publicly formalized as it is today and remained costly. It was wiser to seek prevention than a cure.

A large part of an apprenticeship consisted in living with a master and in trying to understand his attitude. These old masters accepted but a few students at a time22 and only became authoritarian during the period of Lie Tzu.23

When the twisted tree at last shall be my body

Then I shall begin to live out my natural span.

(Meng Chiao, Song of the Old Man of the Hills, 814, p. 64)

If the old wise Taoist takes care of his body and the circulation of chi in his organism, it is because he is preoccupied with the te of the Tao Te Ching. This te points to a path, a way to live, a way to perceive the world, a mental attitude, and an ability to accommodate to what is. For Taoists, it does not consist in spending a thousand lives to straighten the spine but to plan an aging process that lasts but a lifetime. Moreover, for them, to attempt to render one’s body perfectly balanced does not necessarily make for a serene and durable aging. To impose on oneself schemata that seduce one to think one way about the body demands less work than to try to appreciate how the laws of nature evolve bodies so different from one another. This diversity may well have useful functions that conscious understanding is unable to grasp. If we observe individuals who live more than 100 years while maintaining their mental health, we notice that is not necessarily those individuals with particularly supple or well-balanced bodies. The following anecdote illustrates the Taoist point of view.

Tzu-ch’i of Nan-po was wandering around the Hill of Shang when he saw a huge tree there, different from all the rest. A thousand teams of horses could have taken shelter under it and its shade would have covered them all. Tzu-ch’i said, “What tree is this? It must certainly have some extraordinary usefulness!” But, looking up, he saw that the smaller limbs were gnarled and twisted, unfit for beams or rafters, and looking down, he saw that the trunk was pitted and rotten and could not be used for coffins. He licked one of the leaves and it blistered his mouth and made it sore. He sniffed the odor and it was enough to make a man drunk for three days. “It turns out to be a completely unusable tree,” said Tzu-ch’i, “and so it has been able to grow this big. Aha!—it is this unusableness that the Holy Man makes use of!” (Chuang Tzu, 1968, IV, p. 65)

In the same way that a knotted tree survives the others because the carpenter cannot saw boards out of it, a deformed and bent man survives the others because he is never recruited for war or hard labor.24 Lao Tzu approaches this appreciation of biomechanics from another angle, when he declares:

What is most straight seems crooked;

The greatest skill seems like clumsiness;

The greatest eloquence like stuttering.

(Lao Tzu, 1949, XLV)

The wise old Taoists developed a sophisticated gymnastics for the elderly. This sophistication reconciled two necessities:

The yogi tries to open up every joint and mode of respiration directly. He can do it through skillful instructions, with gentleness, but the intention is still to use a direct approach. The population of those days had a healthier postural repertoire than the Westerners of today. In their daily lives, they used the lotus position, the tailor’s position, squatted feet flat on the floor and bottom on top of the heels, sat on their heels, sat T-square (legs extended, back straight up). Using these postures was therefore not considered acrobatic. Most exercises can be performed squatting, sitting in a chair, or standing. Taoist gymnasts prefer to concentrate on the gestures that will have an impact on the respiration without the involvement of consciousness. For example, a number of writings speak of windmill motions. The gymnast rapidly turns his arms clockwise then counterclockwise. The faster the arms turn, the faster the ribs and the diaphragm move and consequently, the more activated the respiration. The choice of the gesture decides what will be stimulated, but the attention does not direct itself necessarily at that moment on the thoracic breathing or on the coordination of abdominal and thoracic respiration. If the exercise is done standing, which is easiest, the attention focuses mostly on keeping the feet well anchored, without violently turning the arms, and counting the number of windmill motions.25

At first glance, this exercise seems too easy; nonetheless, it is very effective. More than that, the Chinese compensate for the lack of mechanical difficulty with length of the practice. If you turn your arms as fast as you can 100 times, you will see that the exercise tones up the postural and respiratory muscles quite well. The idea here is that it is better to exercise regularly in an easy, well-targeted way than to become discouraged by a difficult exercise. We are far from the daily two-minute stretching exercises to solve all of our problems; but we must not forget that these exercises are designed for the retired.

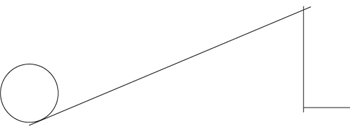

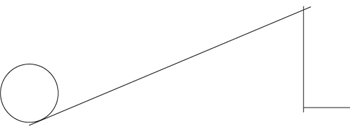

In this section, I detail certain particularities in the Chinese approach from a concrete example. The technical problem is to facilitate the respiration to “go down” to the lower abdomen in a person who breathes mostly from the chest. I describe two effective ways to attain this result. The first is often used by a number of body psychotherapists inspired by Alexander Lowen (see fig. 2.1), whereas the second one probably comes to us from China (see fig. 2.2). It is so discretely effective that, although it is well known by physical therapists, it goes unnoticed in body psychotherapy.

IN BIOENERGETIC ANALYSIS

When Alexander Lowen,26 one of the founders of bioenergetic analysis, gave a demonstration, it was often spectacular and impressive for those who had no knowledge of body psychotherapy. However, even students of bioenergetics could be shocked by the intrusive, sometimes violent, and direct style of these interventions. Here is a description of the way Lowen demonstrates how to bring the breath down to the lower belly.27

FIGURE 2.1. The bioenergetic exercise to activate respiration in the lower abdomen.

FIGURE 2.2. The Chinese exercise of the stool to activate breathing in the lower abdomen.

A vignette on Lowen’s method. Lowen asks a male patient to undress down to his underwear, then to lie down on a mattress. Lowen notices that the patient is not breathing spontaneously from the abdomen. He asks the patient to breath from the lower abdomen. The patient cannot do this. He then asks the patient to keep his feet flat on the mat, knees bent, and to lift his bottom as high as possible;28 and then to hold this position, at all cost, as long as possible while letting the respiration develop.29 He recommends to the patient to breathe deeply with an open mouth; for this way to breath mobilizes the vegetative and emotional reactions. Typically, within five minutes, the participant complains of painful stress. Lowen proposes that the individual face the pain of the stress by expressing the pain and rage that is being experienced by screaming “No!” while hitting the mat with the fists, and by shaking the head from side to side without losing the basic position. At the end of ten minutes, in a rather spectacular way, the respiration of the lower abdomen releases itself and memories of childhood trauma rise to the surface.

This way of doing things is sometimes useful, but if the goal is to liberate the abdominal respiration, then this method is uselessly shocking and sometimes retraumatizing.

THE STOOL EXERCISE

I have found this particularly easy and useful exercise in a book on tai chi chuan by Dominique de Wespin (1973), and have used it with many patients. It generally does not activate the emotional and unconscious dimensions; but this work can be done with other techniques available to the body psychotherapist:

Lie down on the floor. Place the legs up to the knees on a bed.30 Let yourself breathe and just leisurely observe the respiration. It will, little by little, descend to the abdomen, (de Wespin, 1973, p. 137)

It is important that there be a right angle between the thighs and the spine and between the thighs and the calves. As breathing expands, “fanning” the lower belly, it extends itself gradually from the pelvis to the rib cage, thus making more space for the diaphragm to move.

When I have an anxious patient who does not breathe with his belly, I often ask him to try this exercise during the session and then at home. If the chair or stool is too low, one can place a cushion under the calves. This position relaxes and elongates the lower back while relaxing the abdominal muscles. This exercise can easily be done repeatedly in the course of many weeks. This often brings about a lasting relaxation, less fear, and in the end, sometimes, the advent of dreams that provide contact with repressed material. The difficult part of this exercise is to ensure that the patient does not voluntarily direct his breathing. The ideal is that he simply observes what happens. If the patient does not have this capacity, it is better to distract him with a mental placebo, such as asking him to observe what is going on in his feet. When an individual is compulsively self-controlling, we can suggest that he listen to some calm music that he likes during the exercise. This exercise is also useful to detect certain muscle tone problems linked to the way the muscles of the back, abdomen, and psoas influence the position of the pelvis.

I have rarely met someone who does not relax in this position. The respiration gradually relaxes and finishes—in less than ten minutes most of the time—by settling comfortably in the lower belly. Like all exercises, it does not work for everyone. The psychotherapist then tries to understand why it does not work. That leads inevitably to something interesting.

I do not know if this universally known exercise was really invented by Taoists, but it is a good example of how they approach the body. They try to find methods whose simplicity and efficacy are the result of a profound comprehension of the mechanics of the body.

To bring about the awakening of students of all temperaments, the Buddha taught a wonderful variety of spiritual practices. There are foundation practices for the development of loving-kindness, generosity, and moral integrity, the universal ground of spiritual life. Then there is a vast array of meditation practices to train the mind and open the heart. These practices include awareness of the breath and body, mindfulness of feelings and thoughts, practices of mantra and devotion, visualization and contemplative reflection, and practices leading to a refined and profoundly expanded state of consciousness. (Kornfield and Fronsdal, 1993, p. xiii)

Buddhism was developed by Prince Siddhartha Gautama, born in India around 500 BC. When Siddhartha attained a state of illumination, he became a Buddha who founded a movement that is relatively independent from yoga. It maintained the notion that consciousness is a regulator of the organism. Thus only a global transformation of all the dimensions of the organism, and of how the mind perceives the organism, can support the development of consciousness. The Buddhist notion of mindfulness has recently had a strong impact on cognitive and body psychotherapies.31

There is a China before and after Buddhism. Buddhism arrives in homeopathic doses from the third century CE onward and solidly implants itself by the seventh century.32 It brings along not only a philosophy but also knowledge mastered by the Hindus. The Chinese incorporated this immense cultural legacy so well that today it is impossible to distinguish the contributions of yoga from that of the Chinese tradition in the domain of the body techniques. The Chinese martial arts, for example, owe a huge debt to the monks of the Chao Lin temple. These Buddhist monks founded a monastery around 500 CE in the region of Ho-Nan. They created a synthesis out of the Hindu martial arts and the Chinese body techniques that became one of the foundations of most of the body, martial, and therapeutic techniques in China and Japan.

The translators of Taoist books on meditation who introduced the notion of Chinese alchemy were probably influenced by Jung’s alchemical considerations (1953). He supported the translation and the distribution of an eighteenth-century Taoist treatise titled The Secret of the Golden Flower (Tai Yi Jin Hua Zong Zhi).33 The Chinese use the term meitan to designate an exploration that transforms the organism into a psychophysiological laboratory. Influenced by spiritual movements, Jung used the word alchemy in its large sense, to designate a process that seeks to ameliorate the dynamics of the vital energy in a body and thus transform the human organism. The basic European metaphor, the operations used by the alchemists to transform a stone or lead into gold, is similar to those used to reach illumination. For alchemists, one cannot understand how to create gold without becoming illuminated. The alchemical transformation of the organism seeks immortality.

From Lao Tzu to Lie Tzu, the Taoist movement is suspicious of all forms of institutional organizations. At the arrival of Buddhism, some Taoists, inspired by the way the Buddhist monks live an organized monastic life, created similar communities of their own.34 These Taoist monks are the ones who associated the term Taoism to the meticulous pursuit of the mastery of chi. They claimed to be able to circulate chi in multiple ways throughout their entire body. These monks integrated the old Chinese religions, the Taoist philosophy, the I Ching, diverse forms of Buddhism, yoga, and gradually even ideas from European “alchemical” movements. The chi thus acquired magical properties, an extraordinary power, something akin to what certain esoteric movements referred to as vital energy. In their development, they created a “jungle” of schools. Some of them took on the form of sects using black magic and supporting violent political movements. These movements promised health, eternal youth, immortality, joy, and sexual prowess.35 Some sought money and power by using every means at their disposal, such as blackmail, manipulation, prostitution for the wealthy, and deceit. The similarity between the definitions of chi and of the vital energy of Christian cultures intensified during the occupation of China’s maritime regions by Europeans and the United States. This “synthesis” influenced and was influenced by movements such as that of the theosophists.

These Taoist movements had an important influence on the development of Chinese thought as well as on the new body-mind methods. They created theories full of flashy and seductive concepts. They nonetheless deserve credit for having passed on useful ancient knowledge and for having proposed some important ideas like the notion of tan tien (hara in Japan) taken up by the martial arts.36 It is often this movement that represents the Chinese thought in the writings of and courses given by body psychotherapists.

A CHI THAT DIFFERENTIATES ITSELF FROM MATTER

A number of Chinese practitioners divide the dynamics of the organism into passive/active, soft/hard, active/receptive—parts that correspond somewhat to a chart of the yin/yang of the organism. This chart has different nuances from one school to another, but it is often read in the following way:38

At the heart of these great classifications, we find the sophistications of the I Ching. The female sexual organs are yin, but contain important yang modules that are needed when the matrix produces an embryo.

The alchemists take up the respiratory circuit that I already described in the sections dedicated to the pranayama and coordinate it with the wheel of the chi (fig. 2.3) that they also associate with the cycle of the seasons. Everything happens as if chi was some sort of fluid made up of a subtle but powerful substance. This fluid should go up the back during inhalation, having a yang quality, and return yin on the front of the body during exhalation.39 To get everybody to agree, Taoists also speak of an underlying current that moves in the opposite direction. These two directions are well described in the bottle exercise, already practiced by the yogis.

THE BOTTLE EXERCISE

The bottle exercise is a simple exercise, used in a number of schools of bodywork, that facilitates observing the coordination of the segments at the occasion of a complete respiration. When you pour water into a bottle, the water falls to the bottom, then gradually rises up to the rim. You can center your attention on two separate movements:

FIGURE 2.3. The circulation of chi during meditation according to the Taoist alchemists. The points A-E-F-H-I-J-K-L indicate the peripheral circulation of chi. This circulation generally passes from K to O to A, but sometimes passes by L, as during sexual intercourse. The axis P-M-O is the central axis. The point O is the tan tien or hara; point A is the perineum (Yü, 1970, p. 124).

In the bottle breathing exercise, one invites an individual to breathe as if the air is water and the body a bottle. Thus, in exhaling, the air at the top of the lungs comes out first; the air at the bottom of the lungs, linked to a respiratory movement from the lower abdomen, comes out last. This respiration creates a movement from the top to the bottom during exhalation and from the lower abdomen toward the top of the chest during inhalation. In this example, we see that we can pay equal attention to the descending air current as well as to the ascending muscular effort.

THE CENTRAL CIRCUIT: THE THREE FIELDS OF THE CINNABAR

Question. Will you please teach me the proper method of swallowing saliva?

Answer. This is the quickest way to produce the generative force; it consists of touching the palate with the tongue to increase the flow of saliva more than usual. When the mouth is so full you can hold no more and you are about to spurt it out, straighten your neck and swallow it. It will then enter the channel of function (jen mo) to reach the cavity of vitality (below the navel) where it will change into negative and positive generative force. (Lu K’uan Yu, 1970, 2, p. 10f)

Other than the wheel of chi that moves around the body, there exists a central circuit (chung mo or jen mo), an axis, that comes down from the head, passes through the respiratory pathways and the intestines, and ends up in the perineum at the bottom of the pelvis (see fig. 2.3). Like the peripheral circuit, this circuit corresponds approximately only to the acupuncture meridians. This central circuit links together three centers40 that form the “three fields of the cinnabar” (Baldrian-Hussein, 1984, p. 156):

This lower tan tien is the part most often mentioned in the study of the martial arts around the world. When we are standing, it corresponds to the center of gravity, and is thus associated with weight, stability, and the source of the organism’s power. All gestures originate from this center. At the end of an exercise, it becomes the place where the chi gathers for rest. The expression “to be centered” makes reference to these practices.

The tan tien is so important for the Taoists that they developed paradoxical respiration. Habitually, the abdomen expands with inhalation and then flattens with exhalation when the diaphragm ascends to push up the lungs. There is an instance when respiration does not follow this schema: when an individual has a bowel movement. In that instance, the diaphragm descends during exhalation to massage the intestines and push their content downward. The Taoist alchemists and the masters of the martial arts took up this reflex to make chi descend toward the tan tien. This exhalation extends the abdominal segment and lowers the center of gravity to ensure greater stability.41 This apparently insignificant detail corresponds to some important concerns to the martial arts. They associate the notion of being grounded (to lower the center of gravity) to that of centering (to concentrate on the center of gravity).

To better indicate the specifics of the Chinese method, I will contrast, as before, the Chinese point of view to that of Lowen. The concrete example here is a punch.

THE PUNCH AS AN EMOTIONAL EXPRESSION

According to Lowen,42 exhalation accompanies an emotional expression. One reason is that an expression is often accompanied by vocalizations. The entire energy of the body is expended in this action. During inhalation, the organism is rebuilding its reserves to prepare for the next wave of expressions. The punch also needs the support of proper posture, that is, stable feet. The more a person stands solidly on his feet, the more he can use this base to build an attack that adds the weight of the back to the force of the arms. From this point of view, every emotional expression made while inhaling reveals a restraint, a lack of confidence on the part of the person relative to the expression. If we add to that a weak anchoring of the feet, the punch often leads to an aggressive expression that can have harmful consequences for the person throwing the punch. That is often the case with impulsive children when they have a temper tantrum. They hit and scream a lot, but they can get hurt.

A typical way to understand how an individual expressed his aggression in bioenergetic analysis is to explore what is going on when, under the guise of an exercise, he hits a cushion numerous times while yelling as loud as possible. The exercise works particularly well if the individual can imagine that the cushion is someone against whom he feels anger. Typically, the examination conducted during this exercise will be done according to two levels of analysis:

The coordination of the body elements utilized by an emotional reaction is not the same for all the emotions. In grief, for example, the foundation of the feet is often lost because a sad individual would like to be able to lay his head on another’s shoulder and be held. This conceptualization is close enough to that of the Chinese.

The chi-kong of the animals is composed of exercises in which participants imitate different animals in particular ways to reveal certain negative emotions. In the version that I learned with the master Dee Chow,43 one of the exercises integrates in a march movements of crooked fingers that evoke bear claws and possessiveness. In the monkey exercise, associated with indecision, the student walks looking to the right while the hands move to the left, then looking to the left while the hands move to the right. By doing this exercise, one learns precise gestures and emotional associations. Within this containing framework, someone can explore what is happening within while meditating on what these movements activate in his organism.

THE WARRIOR’S PUNCH

If the system of analysis of a master of tai chi chuan is close to the one I attributed to Lowen, the goals are different. A warrior has no intention of being possessed by his emotions. He intends to become effective. He wants to give a punch that is correctly supported by his legs, pelvis, and back. The force comes from the back of the body, not from the arms and the hands. The entire mass of the body brings weight to the punch. Moreover, the thrust of the punch must never go beyond the postural base, defined by the feet, to maintain the mastery of the equilibrium. For as soon as the fist is too far advanced, the weight of the body tips toward the front of the feet and the equilibrium of the body “loses its footing.” The individual is thus no longer centered because of the off-balanced forward thrust in the attempt to hit another; consequently he is now vulnerable to a counterattack. That is why, instead of breathing out in hitting, as the innate physiological mechanisms linked to aggression would have it, the warrior often hits while using the paradoxical expiration and sometimes while breathing in. The message is no longer “I am going to smash your jaw,” but mostly, “you will not make me lose my equilibrium.”

I do not believe the Chinese are “masters of their emotions.” The option developed by Chinese martial arts requires a lengthy and regular training to establish itself. To impose on the organism a way to be and act other than the one put in place by innate biological mechanisms requires an immense effort, a discipline that must be reinforced almost every day through hours of practice. In the face of emotions, knowing never suffices.

Tai chi chuan is a martial art that came of age in the eighteenth century. It incorporates almost all of the Hindu and Chinese knowledge and understanding that I mentioned earlier. Its current form dates from the middle of the nineteenth century.44 This martial art developed a version that is so slow that it makes it possible to differentiate every articulation of every part of the body for a movement that is then executed as fast as lightning. I want to speak about this unending adagio. Millions of students, in China and in the rest of the world, practice this gymnastics. It is related to chi-kong, composed of a few movements that are associated more specifically to health problems and to mobilizations of the meridians. There are numerous manuals and websites that explicitly detail the existence of a link between gesture, the circulation of chi in the meridians, respiration, and the particular work of the joints and of mental images.

Many tai chi chuan manuals describe a series of standardized postures that can be drawn or photographed. Learning the form of these postures is a first part of this discipline’s apprenticeship. In some manuals, the position of the feet and the placement of the body’s weight on each foot are specified. The weight of the body can be divided equally on both feet, in a position (the chi shih) that will be, with a few differences, also a position of reference in bioenergetic analysis (grounding); or the weight of the body can be distributed all on one foot and on the tip of the other, like in the grasping the sparrow’s tail (lan chiao wei).45 Each of these postures is the most clearly defined part of a movement that has a beginning and an end and is to be carried out in a particular mindset. The spirit of a movement that situates a posture in between two others defines itself according to a number of criteria. For example:

When a person takes the chi shih position, he checks that his feet are exactly parallel, equidistant, and even with the width of the shoulders. The knees are unlocked, slightly bent. The arms are relaxed alongside the body. Then slowly, “the individual lifts the wrists forward up to the height of the shoulders, the arms remaining parallel, the elbows pulled downward” (Despeux, 1981, p. 143; translated by Marcel Duclos). When an individual is relaxed, this movement inevitably engages a slight flexing of the knees. The arm rises during an inbreath, and the eyes follow the wrists.

If you try to make this gesture, you will see that to coordinate the movements of the arms with breathing is a task that requires an apprenticeship. To do that in coordination with one’s breath is one thing; but to let the knees flex is yet another! A central notion of tai chi chuan is that when a movement is executed correctly, movement and consciousness follow the laws of biomechanics47 and the circulation of the chi. Consciousness has learned to follow movements that are in harmony with the properties of the organism.

Like the dots of a line, these postures first insert themselves into a series of movements and finish by becoming one long movement where all of the dimensions of the organism move in harmony with each other. The movements are defined by an empirical study of what transitions are the most economical (in terms of physical effort) and the most effective (in terms of combat) to go from one posture to another. The fighter must, for example, deflect a blow, then another, and attack. The sequence from one posture to another follows the rules of the I Ching on the manner in which a structure (or hexagram) transforms itself into another: how to pass from one position of the feet to another, how to change the distribution of the weight on the feet, how to rebuild the position of the pelvis that will sustain a new action (to block a punch and then give one). Only after years of practice can each position and each transition be in such alignment that an observer can have the impression of a continuous, fluid, and harmonious motion that lasts for twenty minutes. Yoga had already worked on how to go from an asana to another. However, the coordination between posture and movement proposed by tai chi chuan is, for me, one of the seven marvels of our present world.

OBSERVE THE FEET MOSTLY, THE FACE A LITTLE

I will now emphasize two implications of what I described in the preceding sections:

THE TWO RESPIRATIONS

We have made the distinction between physiological and paradoxical respiration. This distinction overlaps approximately with two ways to coordinate gestures and breathing.49

By default, the proper breathing for any form of relaxation is the one that conforms to the biomechanical respiratory movement. Every movement that crushes the thorax is associated with exhalation, and every movement that favors the expansion of the thorax is associated with inhalation. In the case of movements that have a contradictory effect on the volume of the thorax, a detailed biomechanical analysis is recommended. An example of this would be when the arms close in on the thorax while the knees move away from the abdomen. In the case of doubt, always let the patient move any way he wants. When a “correct” respiration comes into conflict with the patient’s spontaneity, respect the mechanisms of the patient first and analyze what is happening before confronting the patient’s defense system.

The notions of prana and of chi were developed in a world where the dualities such as body and soul, psyche and soma, or energy and matter did not exist.

The Chinese chi is initially an undifferentiated dynamic matter that serves as the basis for the production of differentiated elements such as fire, earth, metal, water, and wood. Each represents a certain relationship between yin and yang. The immense variety of the dynamics of matter managed by human practices derives from these fundamental forces. The notion of active matter does not have an equivalent in a physics that separates matter and energy.

When we spoke of prana, we saw that all activity that influences attention and breathing (such as the postures) has an impact on prana. Chi is a similar substance but more differentiated. It is influenced by what enters and leaves the body through respiration, but also by gestures and acupuncture needles. Most of the Chinese masters realize that they understand chi only by their ability to influence it, but it would be difficult to define it positively, to explain its constituents.