In the sections dedicated to the theory of evolution, we have mostly discussed the interaction that constructs itself between behavior and environment. Lamarck had also foreseen, in his syllabus for biology, a study of the interaction between behavior and the internal environment of the organism. This second portion of Lamarck’s project is what I now want to address. It is a pivotal theme for body and somatic psychotherapists, because it describes how the interaction influences not only the psyche but also other regulators of the organism.

To fully understand psychophysiology requires the study of physiology and biology. Even if he has not undertaken such studies, a psychotherapist—especially if he works with the body and the soma—cannot avoid being interested in what is known in these domains. The mixture of a psychological clinical model and physiological models is nonetheless problematic for several reasons:

As Philippe Rochat repeats tirelessly in his presentations and writings:1 even an academic psychologist is unable to find his way in the unbelievably complex mazes in the area of psychophysiological research. There is nothing scientific in wanting to act “as if” one understands. It is more honest and often more rewarding if you are a psychologist to defend a psychological model that corresponds to a practice, a familiar know-how, and to articulate its theory without using data from other fields. The clinician can then present his model to experts in psychophysiology, who may not only find some relationships with what they are doing, but will perhaps be inspired by some aspect of the clinical model. However much psychophysiological models may inspire you, they must not be utilized as a scientific guarantee, but as a source of inspiration that allows you to take up your clinical observations and reformulate your models without using the physiological models that caught your attention to validate your point of view. A psychological model only has value if it is based on the observations and notions of psychologists and psychotherapists.

Being both a psychologist and a psychotherapist, I do not have the education that would allow me to summarize the status of the research in contemporary psychophysiology. In the sections that follow, I highlight psychophysiological models that are often discussed by body psychotherapists and must be known to understand the literature in this domain. These models have been selected, a bit haphazardly, by psychotherapists who often ignored a large part of the literature and who do not always have enough knowledge in psychophysiology to know the implications of their choice of model. This is also true for a number of psychiatrists who have a sound initial foundation in psychophysiology and have sometimes conducted fine research as students (like Freud), but who ended up focusing on a particular clinical dimension in which they were interested. Having said that, these accidental choices are useful, as they allow us to perceive what sort of psychophysiology is compatible to what body psychotherapists imagine when they develop a form of intervention. If scientific rigor is not always present in the choice of physiological theories adopted by psychotherapists, the choice is at least pertinent as a metaphor of what is conceptualized in a practice, just as Plato’s fables are often more relevant than they appear at first glance. Research is in effect not only an attempt to understand but also a stimulus of humanity’s imagination that can conceive of realities it could not previously picture.2 In the Middle Ages, no one could have imagined, even in dreams, the images that we now have of the galaxies and cellular life.

The following sections allow today’s starting psychotherapists to acquire a minimum of basic concepts they may then have to shore up by taking courses designed to introduce them to recent refinements. I hope the notions I discuss will help and encourage everyone to more easily consult recent textbooks in psychophysiology.

One of the implications of Lamarck’s theory is that there probably exists in all of the species common mechanisms susceptible to reconstruction in function of their organismic, social, and geographic context.3 Today, the most obvious example of such modifications is the mutations of the genes. In the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, the common mechanisms between the species was the metabolic functioning of the aqueous milieu contained in each organism and the homeostatic mechanisms, which coordinate the requirements of the internal environment and the exigencies of the social and geographic environment.

Two themes developed by the French physiologist Claude Bernard4 (1813–1878) are still discussed in the literature:

This second theme will permit us to situate the notion of the auto-regulation of the organism. This notion had been taken up by those body psychotherapists6 for whom one of the functions of body psychotherapy is to facilitate an organism’s capacity to self-regulate constructively.

In his evolutionary physiology, Lamarck demonstrates that organisms are, before anything else, membranes containing fluids. A way to describe the evolution of anatomy and physiology is to show how the regulatory mechanisms of the fluids evolved.7 The development of the organs relate to a differentiation of the body fluids (venous and arterial blood, lymph, urine, saliva, sweat, tears, etc.). When the nervous system finally appears, it participates not only in the regulation of the fluids but also in the interaction between body movements and body fluids. Thus, the muscular activity that animates a gesture is structured by the nervous system but must also have a pertinent logistic support from the cardiovascular system.

Little by little the idea that the internal environment was nothing other than a part of the ocean that our distant ancestors had taken with them when they passed from an aquatic to an aerial life established itself within me; but that which needed to be revived above all else was the cell. (Laborit, 1989, La Vie Antérieure, 7.3, p. 102; translated by Marcel Duclos)

Claude Bernard has called the water contained in living organism the “internal environment.” A large percentage of the weight of each organism is made up of fluids in which the cells can live and communicate with each other. These fluids have a certain number of particularities that make it possible to distinguish between biological water and the water from a brook. To be able to sustain the ongoing activity of the cells, these fluids must maintain the stability of a number of properties, such as temperature (between 36°C and 37°C in humans) and a neutral hydrogen potential (or pH8). This fluid must be able to nourish the cells and evacuate their waste, and furnish enough free ions (+ and -) to guarantee various forms of exchanges between the cells and the milieu that surrounds them. These exchanges are at the basis of metabolic activity. The maintenance of the properties of the internal environment is the first and main task of a living organism. Claude Bernard found convincing ways of demonstrating that cellular activity can be entirely described and explained by physical and chemical conditions.9 He is one of the scientists who actively sought to exclude vitalism10 from mainstream biology.

The properties of the internal environment cannot stray from their central values without endangering the survival of the organism. It is mostly the warmblooded species that can sustain changes in the ambient climate, for they have the physiological means to maintain a constant internal temperature in conditions that sometimes vary considerably. Yet even humans have difficulty handling changes of more than 60°F in ambient temperature.

In an amoeba, the fluids are hardly differentiated. Their dynamics regulate the solidification of the membranes in the constriction phase, and the softening of the membranes that allows various forms of mobility. This mechanism is a first kind of passage between a form of protection against aggression and displacement as a predator. The amoeba can modify the consistency of its tissues by oscillating between several states:11

1a. Hardening. The quantity of fluids contained in the organism diminishes and the tissues harden. Perhaps here we have the first version of what will become the chronic tension of the muscles, which leads to the restriction of mobility, respiration, and the pleasure in moving.

1b. Hardening is often associated to a disengagement from peripheral activity.

For many physicians, like Wilhelm Reich, some of these functions are found in the more differentiated functioning of the human vegetative system:12

In the same period, the ethologist Konrad Lorenz proposed a complementary analysis concerning the relationship between the mobility of unicellular organisms and human motricity.13 The pulsation of the amoeba is the basis of the construction of the affects of withdrawal (the 3 Fs: flight, fear, and freeze) and attack. Fight and flight are just two of the many behaviors associated with aggression, anxiety, and fear. If I base myself on the current observations of body psychotherapists who work with anxious individuals, we can distinguish two types of fear:14

Another behavior associated with danger that is often observed in a psychotherapy practice is an abrupt immobilization.15 This reaction is used by some herbivores on the savanna when they can no longer escape a big cat. They become immobile and hold their breath to trick the predator into believing they are dead. If the predator is distracted, the zebra can suddenly stand, run, and escape. In humans, we sometimes observe some variations of this reaction, which would be a variation on the theme under way in the evolution of the species by the amoebic contraction.

This attempt to have everything start from the mechanisms of the amoeba is sometimes useful,16 but a bit too simplistic for the clinician:

This discussion indicates how Bernard’s approach made it possible to coordinate apparently purely physiological mechanisms with global behavioral dynamics that mobilize the organism almost in its entirety.

Walter B. Cannon (1871–1945) completed his medical studies at Harvard University, where he then became a physician, a researcher, and a professor.17 The first body psychotherapists hardly ever quote him,18 but they often propose for mulations that were manifestly influenced, at least indirectly, by his theories. Most of Cannon’s models were taught in the biology classes of secondary schools. In other words, for many, Cannon = Physiology.19 His model of homeostasis is the first medical model that describes the capacity of the organism to auto-regulate. It also became a reference for European psychologists of the 1930s.20

At the end of World War I, Cannon was a military physician in France. In Paris, he discovered the work of Claude Bernard and his idea that every organism has, at its disposal, strategies to regulate its internal environment in a changing environment. Cannon then undertook research on the strategies that permit an organism to regulate the internal environment. He refers to these regulatory systems as homeostasis.21

The concept of homeostasis is a precursor of the systemic and cybernetic theories. Like Lamarck and Bernard, Cannon situates the mind in the mechanisms created to enhance the regulatory systems of the internal environment of the organism. This approach does not prohibit other functions from having grafted themselves to the regulatory mechanisms of the internal environment. This point of view is compatible with Darwin’s hypothesis on the emotions, which, like parasites, latch on to the regulatory systems that were not originally conceived for them. Cannon mentions, for example, the observation of Bernard quoted by Darwin:22 that there exists a spontaneous link between certain emotional expressions and cardiac activity. Having demonstrated, in detailed fashion for certain mechanisms, that the affects are associated to diverse physiological mechanisms, Cannon concluded that the mechanisms of internal homeostatic regulation are composed of physiological, mental, and behavioral mechanisms. Other researchers, like Wilhelm Reich (1940) and Henri Laborit (1971), studied how these mechanisms insert themselves into social and political strategies.

I went from the idea that an oyster can only make an oyster shell; a snail, a snail shell; and that a city is nothing other than a shell constructed by a living organism: a human society. (Laborit, 1989, La vie antérieure, 10.1, p. 187; translated by Marcel Duclos)

In humans, the mechanisms of homeostatic regulation often function in association with the mechanisms of relational and social regulation. The regulation of an infant’s temperature cannot be maintained without the help of the parents.23 In a land as cold as Scandinavia, parents would not be able to help their children maintain an adequate temperature if they did not have the proper clothing, housing, and heating systems. It is therefore possible to think that the homeostatic systems of socialized species, like ants and humans, are carried out in social dynamics.

The homeostatic mechanisms of humans only function if they receive a constant social support. Physicians allow themselves to have social requirements (in the matter of hygiene, of nutrition, etc.), which go far beyond the care dispensed to particular organisms. The interpenetration of all of these mechanisms is of an unheard-of complexity that Cannon could not study with the limited means of a laboratory. He contented himself to study the homeostatic mechanisms situated in an organism, that is, the mechanisms that coordinate behavior and the demands of the internal environment. He analyzes, for example, what motivates an organism to seek out the shade, sweat, and drink when the temperature of the ambient air increases. Like most of the authors I have already mentioned, Cannon situates the affects in the center of what coordinates behavior and physiology. The affects would be one of the tools that permit the organism to coordinate mind, behavior, and physiological needs.

Taking up the language of the System of the Dimensions of the Organism (SDO) that serves as the reference point for this textbook, the affects are propensities organized by the mechanisms of organismic regulation to coordinate the dimensions of the organism in function of a goal structured by one of the dimensions. There are several types of affects.

The homeostatic instincts form at least two types of propensities:24

The instinctive affects have as their first goal the mobilization of the power25 of the organism for a task linked to survival.

Other types of affect, well known to psychiatrists, are the moods, like depression and euphoric mania. Some practitioners have a tendency to place depression and anxiety on the same plane. They consequently use the word mood to designate these two affects. Psychiatric and psychotherapeutic practice often compares and contrasts depression and anxiety on an axis different than the contrast between depressive and manic states.26 For Andre Haynal,27 for example, depression is often the regret for a past that never existed, and anxiety, the fear of a future that will not come about. This formula was often useful to me in my practice.

In psychiatry, the term mood designates all the affective systems that can be easily influenced by medications because their organization depends largely on the physiological mechanisms that are structured around the vegetative, cerebral, and hormonal mechanisms. The positive moods are those that participate in the constructive regulations for the integrity of the organism; the negative moods are linked to the regulations that accelerate the deterioration of the organism. This usage rejoins the meaning the term has when someone says they woke up in a good or bad mood.

Like depression, a mood can be triggered by a specific event; the length of time during which it lasts is greater than the status of a simple response or reaction to a stimulus. A mood often presents a cyclical face, independent of circumstances, that makes one think of a genetic factor. The formula that prevails, since Freud, is that of a genetic predisposition that can be modulated by events. A predominant mood in a patient is often found markedly28 in the family history. In psychotherapy, by default, I propose that the patient learn to live with his moods rather than desire to master the moods.29 The disappearance of a significant tendency toward cyclical depression or anxiety is rare, although it can sometimes be observed. The reason for the stability of these moods becomes apparent as soon as we admit that there is a link between mood and particular forms of homeostatic auto-regulation which engenders a lifestyle and a style of communication. Therefore, to reduce the rhythm and the intensity of the mood swings requires taking into account the coordination between a lifestyle, a way to behave and think, and the modulation of the mechanisms of homeostatic regulation. Sometimes, changes on all these levels are necessary; sometimes a well-localized change modifies the entire system. The prognosis is better when the patient lives in a supportive environment.

All the passing moods have a constructive value for the organism, if we admit that they are a type of homeostatic regulation (anxiety before an exam can be useful) to a situation whose contours are relatively clear. As soon as a mood becomes habitual, it associates with a multitude of regulatory mechanisms of the organism. If this mood inserts itself in a person’s character, it ends up becoming a permanent form of regulation for the organism. By associating itself so profoundly with a particular mood, it makes them less available to other moods. The organism therefore loses its flexibility and diminishes its capacity to adapt.

I take the case of the depressive affect in a person who suffers from obesity30 to detail the deep-rooted nature of a mood in the physiological dynamics of an organism. To do so, I detail a part of the connections between depression and the consumption of carbohydrates:

As we can see in these examples, the link between carbohydrates, serotonin, insulin, depression, and obesity is almost unsolvable without a profound change in the social functioning that participates in the formation of the eating habits. This explains the failure of most of the interventions related to obesity. In the elements I have summarized, we can see that each variable has a series of implications and branch lines that can activate mobilizations with contradictory effects. As it happens, the rapport between a change of diet and depression can be caused (a) by the psychological difficulty to accept a change of habits, and (b) by lowering serotonin production. In this model, there are two distinct causal systems that reinforce a depressive mood.

As soon as a practitioner attends to the respiration of his patients, he notices that some people can be considered “oxygen anorexics.” When he asks his patients to breathe deeply, many feel “dizzy.” They need to reduce the volume of their respiration or reduce the increase of metabolic energy by moving, or by hyperventilating. The reeducation of the metabolism of respiration cannot be accomplished only in the context of psychotherapy, because such a change requires the regular practice of breathing exercises, as this is done in pranayama training, in the Pilates method, in sports, and so on. Thus certain forms of hyperactivity (constant chatter, the need to move incessantly, etc.) can be explained by a physiological incapacity to “digest” an increase of the metabolic activity.

The following is a way to explain “anorexic” respiration, that is presently taught in several body psychotherapy schools (e.g., in Bioenergetics analysis):

I have observed this vicious circle, for example, in patients whose parents needed to be protected from the intensity of their children’s needs.36 Other persons act before having the need to (eat as soon as they are aware of the slightest hunger, masturbate as soon as there is the slightest sexual desire, etc.). In this group, we often find individuals who have little tolerance for frustration and who act impulsively. They prefer many small frustrations to intense ones.

As we can see in these examples, metabolism is a dimension the psychotherapist has not learned to understand in a detailed manner, but which could be useful to him to keep in mind. Reducing the intake of oxygen reduces the metabolic activity and consequently the energetic charge that all the dimensions of the organism need to have available to them. The relationship between the dimensions and metabolism is evidently cybernetic: the influence is asymmetrical (not of the same type) but reciprocal. Thus, the metabolic activity depends on breathing and eating behaviors. The available energy can then be dispensed in many ways: by moving, by thinking, by storing lipids, and so on. This domain is what the biochemists often call “bioenergy.”37 In my point of view, it is mostly these chemical dynamics that make it possible to give an account of the whole of the energetic dynamics of an organism.

In the domain of body psychotherapy, Alexander Lowen proposed the term bioenergy to designate what Wilhelm Reich called the orgone. Charles Kelley followed a similar reasoning when he called Reich’s38 cosmic energy “radix” (root). The use of a scientific term to designate a notion considered unscientific in academia did reveal itself to be lucrative in terms of clients, but it reinforced the rupture that developed between academia and Reichian therapies. Even Reich would probably have objected to a procedure that is manifestly a mystification. To justify this approach, the neo-Reichians discredited the chemistry of the chemists as an inanimate mechanic; on the other hand, their Reichian energy was presented as being full of the vitality that generates the universe. Yet an inverse argument could be directed at these Reichians who reduce the chemical dynamics to something foolishly mechanical. They know so little about chemistry that they fail to grasp the unbelievable creativity that is activated thanks to the chemical and atomic operations. Enhancing the value of theories like that of the orgone often covers up ignorance of the chemical dynamics and their creativity, all the while wanting to give the impression of being omniscient.

The first observations of the vegetative or autonomic nervous system goes back to Claudius Galen of ancient Rome; but John Newport Langley (1899) is generally recognized39 as the first to have proposed a correct vision of the structure and the function of this system. Cannon uses the term autonomic, which prevailed in the Anglo-Saxon literature, whereas Reich follows the Germanic tradition in using the term vegetative:

Cannon’s research on the vegetative system tries to demonstrate that it is one of the central mechanisms of the homeostatic system. An increasing number of researchers indicate that the vegetative system is also associated to the emotions. Levensen (2003), for example, showed that it is possible to associate some emotions to some types of activation of the autonomic nervous system. He is able to associate the basic emotions, as distinguished by Ekman42 to distinct vegetative activities. Thus, happiness reduces the electric activity of the skin, and this activity is elevated when the emotion is negative (anger, fear, sadness, disgust), or the cardiac activity is particularly low when a person feels disgusted.

Cannon was the first to give as much weight to the chemical as well as to the neurological dimension of the vegetative system:

Therefore, there is not only a sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system but also sympathetic and parasympathetic functions:

Certain organs, like the heart and the digestive system, are influenced by these two systems. Thus, the sympathetic system accelerates the cardiac rhythm and slows down the peristaltic activity of the digestive tract, while the parasympathetic system slows down the heart and accelerates the peristaltic activity. The more active the body, the greater the mobilization of the sympathetic system, which can be qualified as the vegetative support system of the action. The less active the body, the greater the mobilization of the parasympathetic system, which actively contributes to the state of relaxation and sleep.

In certain cases, the nerve and hormone pathways have the same effect on an organ.45 The vegetative regulations coordinate the moods and the overall condition of the organism. The vegetative coordination is mostly nonconscious but sensitive to the impact of the central nervous system (especially on the striated muscles). This explains why individuals can influence these systems by indirect modalities (breathing exercises, relaxation, yoga exercises, etc.). The vegetative system is part of the mechanisms of organismic regulation. It is consequently used in most of the interactions between the dimensions of the psyche and the body.

Recent research shows that vegetative dynamics are more complex than what Cannon’s generation of physiologists thought. For example, there is more chemical vegetative activity than what was previously assumed by Cannon and Reich.46

In the subsequent sections, I illustrate Cannon’s general understanding by quoting more recent works. They show how the affective and vegetative systems insert themselves into both the fundamental physiological functioning, like the peristaltic activity, and the activity of the central nervous system.

ANXIETY INHIBITS THE PERISTALTIC ACTIVITY

At the end of the nineteenth century, while he was still a student, Cannon worked with X-rays, which had recently been made operational, to explore the physiological functioning of the digestive system. He accidentally discovered that an emotional disturbance blocks the motor activity of the stomach, and the return to a more serene state promptly restores the peristaltic movements of the digestive tract.47 This research confirmed the observations that a general practitioner, William Beaumont, had made on one of his patients.48 Edmund Jacob-son, who had been a student of Cannon, undertook research in psychophysiology in Chicago, and he established that anxiety influences not only the stomach but also the motility of the duodenum, the esophagus, and the colon.49

Between the two world wars, most physicians and psychologists thought that the emotions influenced the behavior of the digestive tract.50 Like the rest of Cannon’s work, this theme disappeared from serious discussions during the 1960s without being invalidated.51 It was considered trivial and without influence on the evolution of psychosomatic practice and theory. Trygve Braatoy,52 for example, mentions as if it were self-evident that the releasing of the stretching reflexes and of yawning, as well as peristaltic gurgling, are an evident sign of relaxation that often accompanies—in a spontaneous way—a postural and muscular release.

THE PSYCHOPERISTALISM OF GERDA BOYESEN

In the 1960s, going against the general trend, Gerda Boyesen, a Norwegian clinical psychologist and physical therapist, developed forms of intervention in body psychotherapy that were based on listening to the peristaltic sounds of the sigmoid colon53 with a stethoscope. The basic principle is that any intervention that returns movement to the peristaltic activity is pertinent to the restoration of the organism’s systems of physiological auto-regulation. This work is founded on the hypothesis that the peristaltic process can be activated by digestion or mechanisms linked to the release of stress. In the case where the mobility of the digestive tract is associated to affective dynamics, Boyesen speaks of psychoper-istalism.54

Currently, psychotherapists who practice this method use electric stethoscopes with loud speakers to detect rapid changes in the motility of the colon:

The event associated with the change of peristaltic activity can be a gesture, a mental association of the patient, a smile of the therapist, a particular way to massage, a change of light in the room, and so on. The therapist and the patient therefore inquire together about what happened at the crucial moment and give a particular importance to these events. The method used for this inquiry is free association. Having said that, it is impossible to know with certainty what event is really associated to each change of peristaltic activity. The relevance of a series of thoughts, conceived at a particular moment, can be confirmed by its impact on the therapeutic process, or if its association with a peristaltic change repeats itself. This method is useful to distinguish two types of utterances:

One of Gerda Boyesen’s hypotheses is that any topic accompanied by a return of peristaltic activity is susceptible to being integrated by the patient, whereas any subject that provokes a slowing down of the peristaltic activity can be indigestible for the patient’s psyche. In any case, Boyesen recommends to her students that they consider this method only as a tool whose relevance depends on the context of the therapeutic process. We are in a world where a bodily event can have many causes. The peristaltic motility is, above all, regulated by the sympathetic (reduction in the activity of the intestines) and parasympathetic (increase in the noises), each of which have multiple functions. Anxiety keeps an organism in a sympathetic state even during a relaxation exercise.

An example that demonstrates the danger of thinking that there is a direct link between relaxation, the parasympathetic system, and gastric motility is the observation that during some states of relaxation, peristaltic noises often cease. We can then evoke a number of hypotheses:

When such questions arise, the therapist needs to use other forms of inquiry before he can find the correct interpretation. This approach is useful in that it helps the therapist narrow the range of questions that are relevant at a particular moment in the therapeutic process.

THE “SECOND BRAIN” ACCORDING TO GERSHON

Michael D. Gershon’s book (1998), titled The Second Brain, announces a new approach relative to the rapport between the intestines and the brain. He demonstrates that the enteric nervous system, situated around and in the digestive tract, is an immense mass of nerves that function parallel to the brain. Traditionally, this system is considered as the part of the vegetative nervous system which is the most autonomic part with regard to the central nervous system. This immense mass of nerves also supports the production of many neurotransmitters made in the intestines. Notably, three-fourths of the serotonin available in a human organism is produced in the intestines. This substance is used in most of the antidepressant medications. The synthesis of serotonin may depend on the quantity of carbohydrates contained in food.

Gershon’s model55 on the connection between depression and the gastrointestinal system is an example of multiple and indirect links between the psyche and soma. The nerve connections that link the intestinal system and the spinal column are rare, and none of these connections has a direct access to the central nervous system.

This area of research has not verified the link between peristaltic noise and moods because it is probable that the link expresses a weak positive correlation, given the multiplicity of implied variables. For the practitioner who uses methods like those of Gerda Boyesen, this means that when the practitioner hears a definite effect, it is probable that Cannon’s model remains relevant. But as soon as we enter into an attempt to explain difficult clinical complexities, Cannon’s model becomes less pertinent. The studies on the intestinal system allow us to refine two ways to approach psychoperistaltism that clinicians had identified with regard to the diverse forms of relaxation mentioned earlier:

It is altogether possible, from there, to take up a dialogue between the body psychotherapist and the researcher; but this dialogue will necessarily take some directions that the psychotherapists had not necessarily anticipated. The correlation is not, after all, between a behavior of the gastrointestinal system and a mental behavior but between a functioning of the digestive system and a functioning of the affective system. At first, the clinician works with a simple labeling system; as the research progresses, this strategy must often be replaced by one that is more complex.

The basic thesis defended in the subsequent sections is that the mechanisms which lead to stress are useful in situations that spontaneously occur in a natural setting; but that they lose their relevance in situations that have been recently produced by civilization. They can then become dangerous for the survival of the organism.

The survivors wanted to erase from their memory the ten million victims who died uselessly and to forget themselves and their tragically wasted and lost years. (Manes Sperber, 1976, “Malraux and Politics,” p. 201; translated by Marcel Duclos)

World War I was particularly traumatic for Europe for at least three reasons:58

The result of this situation was that a number of soldiers were profoundly and permanently traumatized. Their hospitalization mobilized the resources and research of countless physicians because no theoretical framework existed to understand the disastrous psychophysiological state in which these soldiers found themselves. The theories of stress I summarize in the following sections are based on attempts (often only partially beneficial) to support the soldiers traumatized by the war. The limits of these modes of intervention illustrate that it is not possible to heal all ills with a medical perspective. Other solutions, more political, are certainly necessary.

EROS AND THANATOS

Several military hospitals consulted the psychoanalysts who had built their reputation on the treatment of certain forms of trauma. Because the treatments they developed were useful in certain cases, more and more psychoanalytic psychiatrists were hired by hospitals, where they sometimes assumed important positions.59

Nonetheless, traumatized war veterans responded only moderately well to the psychoanalytic treatment. The psychoanalysts had particular difficulty understanding why certain horrible nightmares regularly invaded the soldiers mind after the war, when the organism was no longer under threat. Freud had grown weary of the incessant slaughter and the lies, of the politicians of the time. He (1915d) viewed humanity with an increasing bitterness. The only way he had to make sense about what was going on was to postulate the existence of a destructive instinct (Thanatos) aimed at self and others that was at least as powerful as the pursuit of pleasure (Eros).60

Freud’s first theory attempts to construct itself, like Wallace’s theory, around a single principle that is almost a “nonlaw.” Therefore, Freud proposed that the psyche structures itself around the pursuit of sexualized pleasure. He advanced in this direction, in spite of the severe critical opposition of psychiatrists like Carl Gustav Jung who were willing, if need be, to admit to a basic life force (élan vital) that was not necessarily sexual. It is difficult for someone who works with individuals who suffer from schizophrenia to admit that their problem reduces itself to a fear of sexuality. In analyzing the descriptions of the behaviors of those traumatized by war with his colleagues, Freud had to admit that the psyche cannot be explained by only one principle. He nevertheless had confidence in his analysis about the relationship between libido and neurosis. He therefore took up, in part, Jung’s argument; he postulated that the impulses of life are differentiated into survival forces through violence and survival forces through sexual pleasure. In these two cases, he notes an autoerotic component (masturbation and self-destruction) and a component directed toward the exterior (copulation and combat).61

THE ORGANISM ACCORDING TO GOLDSTEIN

Kurt Goldstein (1878–1965) was a German neurologist who is known for having studied the lesions that cause aphasia from a perspective influenced by Gestalt psychology (see the Glossary). This influence led him to demonstrate how a local lesion inscribes itself into the global dynamics of the brain and then of the entire organism. This position was original and courageous at a time when most neurologists associated psychological functions to specific areas of the brain. He had been trained by preeminent figures who defended the cerebral localization approach, like Carl Wernicke, who, with Paul Broca, discovered the areas of the brain linked to language.

Goldstein had participated in the medical care of German soldiers traumatized by World War I. He had noticed that it was impossible to find a precise organic locus to be treated by a specific medicine that could alleviate the suffering of these soldiers. Independently of Cannon, he was probably the first neurologist to propose a neurological model that situates the nervous system as a global subsystem in the organism.

Persecuted by the Nazis, he fled first to Amsterdam, where he wrote The Organism (1939). When he immigrated to the United States, this work was published with an introduction by psychologist Karl S. Lashley, who was renowned for his studies on the cortical basis of motor activities. The Organism is the first scientific book that explicitly associates the entity that is a human being to a holistic notion of the organism. Kurt Goldstein’s organism is as coherent as Spinoza’s systems. This vision created such a salutary contrast to the neurological literature of the day that it filled the intellectual world with enthusiasm. The work was read by an entire generation of body psychotherapists like Gerda Boyesen (2001, p. 33) and Malcolm Brown (2001) who called his school Organismic Psychotherapy in honor of Goldstein.62 He also had an important influence on neurology (Lashley, Luria, and more recently Edelman) and philosophy (Ludwig Binswanger, George Canguilhem, Ernst Cassirer, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty).

Kurt Goldstein63 details, in an explicit way, the methodological obstacles that make the analysis of the global organismic system difficult. He supposes that a living organ does not function the same way in its natural environment as it does in a laboratory.64 It is also probable that certain functions of the brain are not highlighted unless we can understand how the brain integrates itself into the organismic system. Forty years later, this methodological remark received the support of specialists in animal behavior. They had noticed that the observations of animals in captivity only partially resemble those of the animals living in their natural environment.65 Today, neurologists who use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirm this analysis when they observe how a brain functions while a person performs a specific psychological task.66

In his studies of traumatized individuals, Goldstein distinguishes the feelings that are associated to an explicit cause from those that do not seem to have a cause. It is mostly the second type of affects which haunts the traumatized persons. Goldstein noticed that the individuals who do not succeed in relating their fears to an identified aggressor also often lose their sense of identity. Many psychotherapists follow this distinction when they distinguish between emotions with or without “an object.” For a great number of psychoanalysts, an emotion without an object, of necessity, has a repressed unconscious object. Today, certain psychotherapists who specialize in the disorders caused by trauma recommend, on the contrary, that the emotions without an associated cause be addressed at the start of therapy. I single out this discussion because it seems important to me to become particularly attentive as soon as a person speaks of affects without objects; however, the status of these affects remain a topic of research for which no satisfactory answers have yet been proposed. When a patient speaks to me of affects without objects, I know I must explore what is going on with him when he has this sort of experience.

FLIGHT AND FIGHT ACCORDING TO CANNON:

THE DANGER OF LOCAL SOLUTIONS THAT GLOBALIZE

A military physician for the U.S. Army during both world wars, Cannon developed other means of support for traumatized soldiers. One of the approaches he proposed (1915) to deal with the organismic dysfunctional state observed in traumatized persons, is to focus on the two basic reactions in the face of aggression: flight and fight. These two forms of reaction mobilize all the resources of the organism for a goal that is relatively clear. This mobilization only ceases once this instinctive reaction is inactivated.

To understand the nature of stress, Cannon takes up the Darwinian idea that certain pertinent adaptive mechanisms of the species can become dangerous for survival when they are inherited by another species. The mechanisms mobilized by traumatized humans would be based on the reactions of flight and fight elaborated by other mammals. This system of adaptation remains relevant for humans when they undergo a manifest aggression of short duration, as when a person is physically threatened by another at the occasion of an attempted robbery. The contour of the aggression is fuzzier during a war, or when one is being harassed by colleagues. In such cases it is difficult to know when the danger begins and ends and how to find a form of flight or fight that is relevant. Often, there is no precise predator, as the danger can come from several sources in unpredictable ways. These forms of aggression are generated by institutions. It is then difficult to know against which predator to direct a flight-or-fight response.67 When the reactions of flight or fight are mobilized to react against an aggression such as war, their activation is often automatic. They instantly mobilize all the resources of the organism. During a war, an individual attacks and is being attacked, but the aims are defined institutionally. A soldier may not only be afraid of enemies. He can also find it difficult to accept that he has to kill others. An individual who is being mobbed often does not know why he is being persecuted or who organizes the mobbing. He just feels disempowered. He cannot prevent the activation of a flight or attack response that automatically activates itself in his organism, even when it is counterproductive.

Once in place, the response mobilizes the affective and intellectual resources to react in a particular fashion. They are monopolized by the need to flee or attack. There is no energy to look for other options. To resolve this difficulty, researchers like Lazarus and Folkman (1984) propose methods that facilitate change in the cognitive behavior of traumatized persons to help them construct other forms of adjustment (coping skills) in the face of a real or imaginary danger. The traumatized person needs external help to cope with the flight-or-attack response that has been activated by their organism. Yet he is often too proud and too ashamed to look for help.

To understand the mobilization of a fight-or-flight response, Cannon focused on the association between the activity of the sympathetic nervous system and the increase in the rate of adrenaline in the blood. This hormone is secreted by the central part of the adrenal glands (the medulla) situated on the top of the kidneys. In a cat, the increase in the rate of adrenaline in the blood, set in motion by the sympathetic nervous system, brings about an increase in respiration, cardiac rhythm, and goose bumps. Adrenaline also creates increased irrigation of the muscles and the brain, enlarges the diameter of the pupils, and facilitates access to the energy resources such as sugar.

Since Cannon’s time, Levine and Frederick (1997) have described how, in the animal that survives an attack, this kind of mobilization is followed by vegetative reactions that permit the organism to recover its strength and energy. The animal trembles and evacuates everything that was accumulated at the occasion of the slowing down of the visceral and renal functioning. Going from a sympathetic functioning to a parasympathetic functioning is only possible once the predator is clearly absent. If the hunted animal is caught, he is killed and eaten. In that case, there is no need for a mechanism to shut down the stress reaction. This is a flaw that humans have inherited. In our case, when there is no clear ending to a stressful situation, the mobilization of stress can be activated until the stressed person dies.

THE GENERAL SYNDROME OF ADAPTATION

Hans Selye (1907–1982) was one of the researchers who pursued the work of Cannon on trauma during World War II.68 This Canadian of Austro-Hungarian origin introduced the term stress in 1946.

One of Selye’s basic hypotheses is that when a person must suddenly accommodate to a particularly shocking situation, he often finds a way to function that allows for survival by developing powerful modes of accommodation in very short time.69 But then something is blocked, and flexibility is lost. As I have often indicated, the organism needs time to structure itself. In traumatizing situations, a sudden reconstruction of certain modes of functioning can save the life of the organism, but then the organism has difficulty getting out of this state. Everything that happens after that is assimilated by the new mode of functioning. The organism thus loses its capacity to reaccommodate itself70 to an environment that no longer has a traumatizing dimension. The frozen accommodation does not include the entire organism but focuses only on some organismic systems.

Different than traumatic situations (such as being arrested and then tortured), stress designates more progressive changes. Selye (1936) then talks about the general adaptation syndrome. This syndrome is unleashed by an accommodation in three phases:

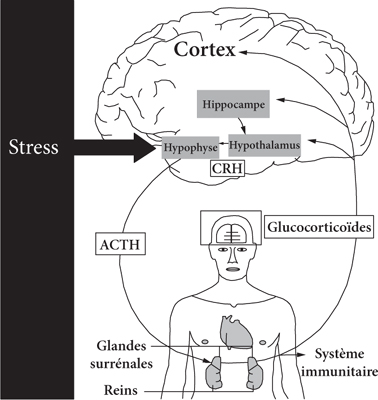

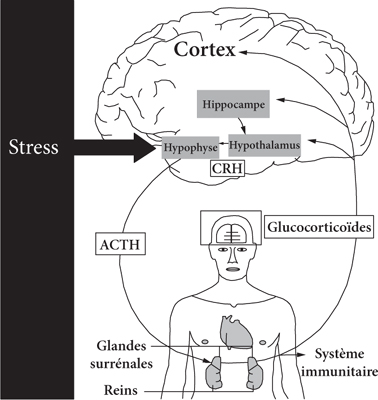

The Activation of the Organism by Stress. Selye isolated an axis of stress that is organized around a reciprocal influence between the hypothalamus in the brain and the median part of the suprarenal endocrine glands, situated at the upper extremity of the kidneys (see figure 8.1). The hypothalamus activates the suprarenal glands through the neurovegetative system. The suprarenal glands secrete catecholamines, like adrenaline and noradrenaline, into the blood. These hormones unleash a classic sympathetic mobilization. This process, shown in figure 8.1, forms a loop of negative retroaction where the excess of Cortisol activates the glucocorticoids receptors of the brain and suppresses the production of CRH. In depressed patients, however, this loop no longer functions, hence an excessive production of CDR and thus of Cortisol. This system is known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

FIGURE 8.1. The axis of stress (or hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal [HPA] axis). When someone suffers a stressful event, his rate of glucocorticoids in the blood increases. This brings about, via specific receptors situated in the hippocampus, an activation of the hypothalamus, which then secretes corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH). This hormone, in turn, activates the pituitary gland (or hypophysis) to produce ATHC (adrenocorticotropine), which circulates in the blood system and reaches the suprarenal glands, where they provoke the release of cortisol. Source: Retrieved on September 29, 2007, from a site dedicated to Henri Laborit: http://lecerveau.mcgill.ca/flash/a/a_08/a_08_m/a_08_m_dep/a_08_m_dep.html

The activity unleashed by the catecholamines allows all of the reactions produced by the axis of stress to draw from energetic resources of the body by metabolizing lipids and sugars. In activating the hypothalamus, this circuit makes it possible to draw more deeply from the organism’s reserves.

Other layers of the central nervous system, situated underneath the hypothalamus, can also activate the adrenal glands. These regions are situated in the medulla, the marrow, and some reflex pathways. A lack of adrenaline in the blood can also activate the adrenal glands via the mechanisms of homeostatic regulation. The hypothalamus can be influenced by other centers of the brains, especially those that govern perceptive and cognitive analysis or the emotions.

This phase of stress is considered to be constructive because it predisposes the organism to become creative. If a resting phase (a small cup of tea) ensues, the organism restores its forces.

The Stress Reaction. The stress reaction varies in intensity according to (a) the danger and (b) the way the stress is felt by the mechanisms that regulate the reaction. Richard S. Lazarus (1991) analyzed how certain mental reactions could activate or deactivate a stress. He sought to define the means with which to cope with stress. Selye thought that the axis of stress, once it was activated by a mechanism that is still not well understood, reacted in an undifferentiated manner. Since research has shown that the vegetative system is less “autonomous” than was believed, this statement has been marginalized.

THE ORGANIZATION OF THE DEFENSES AGAINST EXHAUSTION. If the Organism is repeatedly placed under stress, the axis of stress runs out of easily available resources. To continue to function, it sets about to draw from those resources that are more difficult to use and activates mechanisms that slow down the reactions of exhaustion. The organism sets itself up in a state of accommodation to the shock. The HPA axis is reinforced by an increase of chemical activity that doubles the activity of the sympathetic nervous system. The activation often begins with the hypothalamus, which recruits the help of the pituitary gland this time. The pituitary then secretes corticoliberin, which will produce a hormone called adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), also known as corticotropin. ACTH activates yet a greater number of the adrenals, which in turn, among others, will activate the corticoadrenal hormones, which are released by the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus. It then activates the adrenal gland, which will release hormones such as the glucocorticoids, like cortisol and cortisone. These hormones mobilize the reserves available in the form of carbohydrates and add “slow” sugars into the blood. They inhibit the antiallergic and antiinflammatory manifestations caused by the damage to the tissues during the stress reaction by diminishing the activity of the immune system (especially eosinophils).

At the moment when this system becomes established and can no longer be curbed, there will be permanent vasodilation in the organs necessary for a reaction of fight or flight and a permanent vasoconstriction in the organs dependent on the parasympathetic circuit. This vasoconstriction is in part noxious to the tissues that depend on it and impedes the disposal of the metabolic waste produced by the muscles in permanent tension:72

We were brought to consider the shock syndromes no longer as an exhaustion of the means of defense; but, to the contrary, as a consequence of their activation and of the persistence of their action in the case of the ineffectiveness of flight or fight. (Laborit, 1994, 2.2.2, p. 236; translated by Marcel Duclos)

THE EXHAUSTION REACTION. The large consumption of carbohydrates reduces the production of other substances that depend on it, like serotonin. As we have seen, a reduction of serotonin can produce depressive and suicidal tendencies. These tendencies sometimes are linked to bulimic crises which seek to compensate for the lack of production of substances like serotonin. Stress can manifest through two distinct mechanisms:

These two mechanisms are activated in parallel fashion. They mutually influence each other, but follow a different causal pathway. The feelings of disempowerment and depression that follow the exhaustion phase are thus accompanied by depressive affects like anger at oneself and one’s powerlessness. The organism has fewer and fewer resources. The waste products in the muscles are not eliminated, breathlessness sets in, the arteries and the heart function poorly.

An excess of Cortisol lowers the immune defenses, but it also attacks tissues of the central nervous system, which it saturates via the bloodstream. At the beginning, this effect is stimulating because it allows the ions of the nerve membranes to circulate more rapidly (it consists especially of the circulation of calcium in the membranes). Once this chemical reaction has been exploited, the neurons are in turn exhausted, and sometimes die, due especially to depolarization. Several studies describe a reduction in the volume of the hippocampus in persons who have lived through this form of sudden accommodation.73 The hippocampus, situated in the limbic system, is especially implied in the management of memory and spatial relations. The attack on this neurological structure causes uncontrollable psychological reactions of disorientation. The glucocorticoids also excite other regions of the brain. They modify the functioning of the frontal lobe, which can explain why persons under stress often make poor decisions. They also excite the amygdala, which increases the feeling of fear. The amygdala reinforces the activity of the pituitary while the hippocampus can inhibit it.74

Certain attacks to the hippocampus can be repaired by taking antidepressants, which is one of the reasons they are prescribed. This implies taking these medications during a prescribed time (at least a year) to restructure zones of the hippocampus that were destroyed by stress.75

Henri-Marie Laborit76 (1914–1995) was also influenced by the study of the shock that unsettles soldiers at war. He was a surgeon in the French navy during World War II and during the last French colonial wars (Indochina and Algeria). In the latter part of his life, he became a kind of Spinoza of biology who shows how each system actively influences the system that contains it. Laborit77 arrives at similar conclusions as Spinoza with regard to human beings when he shows that the mental system cannot be conscious of the nonconscious mechanisms by which it is regulated. One of his principal preoccupations seems to have been to find a way to understand how an individual, entangled in systems of regulations that go through many levels (atoms, cells, organisms, institutions, ecology), can actively and lucidly participate in what animates him. This theme gradually became a form of individual and social engagement.

Laborit’s research observes mechanisms that enrich the models of Bernard, Cannon, and Selye. He describes in greater detail how the regulatory mechanisms of the organism are like a bridge that links the cellular and social dynamics. Like a bridge, the homeostatic mechanisms are rooted in two shores. Thus, the food industry makes it possible for human organisms to feed themselves, but it uses this support to render individuals dependent on a system that exploits them. He describes in a detailed way the chain of mechanisms that connect cellular, organismic and social dynamics. This allows him to provide an enlarged panoramic view of the heterogeneity of the mechanisms involved in the homeostatic regulation of the human species.

THE INDIVIDUAL AND HIS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT

Henri Laborit78 knew and admired Selye.79 For both of them, one could only alleviate the destruction of the cells by seeing to the equilibrium of the internal environment and by keeping its values as balanced as possible. His first model on the biology of stress is close to the one Selye was developing. They were using different but complementary research strategies to analyze how stress could destroy some of the organism’s tissues. Laborit’s first original contribution to that area of research was based on his observation that an amelioration of the ecology of the cells was only useful if the cell modified its behavior in function of this amelioration. Because of this finding, Laborit and his French colleagues focused on the “pumps” in the cell membrane that facilitate the exit and entry of substances. You will find detailed descriptions in textbooks on physiology that show how the cell membrane polarizes and depolarizes by passing ions from both side of the membrane:

When a cell depolarizes itself, the sodium, whose concentration outside of the cell is greater than in the interior of the cell, penetrates within. Conversely, the potassium, whose intracellular concentration is elevated, in the course of the depolarization, exits the cell toward the extracellular milieu. (Laborit, 1989, 7.3, p. 102; translated by Marcel Duclos)

This exchange requires that there is enough sodium and potassium in the internal environment of the organism. However, Laborit observes, in certain circumstances, the sodium and potassium pumps become inactive. The restoration of equilibrium in the internal environment does not suffice to restore the activity of the pumps.80 Therefore, Laborit sought to find those substances that would restore not only the internal environment but also the activity of cellular pumps. Here, the action is doubled:

Without this dual action, not only do the individual cells waste away but also their participation in the maintenance of the equilibrium of the internal environment becomes defective. A negative vicious circle is then established in which the disequilibrium of the internal environment renders the cells inactive, and the inactivity of the cells destabilizes its immediate environment. At the beginning, this disequilibrium is local; but if it persists, it can invade the organism. Indeed, the exchange of potassium and sodium between the internal environment and the cell adjusts the equilibrium of the substances in the organism’s internal environment. If some cells retain one of these, there is a possible disequilibrium in the internal environment that can create a lack of supply in other well-functioning cells. Moreover, the death of some cells can set toxic wastes like lactic acid in circulation in the internal environment of the organism. This can create a metabolic acidosis. It can also modify the equilibrium of the internal environment.81

Laborit goes from this model between the cell and its immediate milieu when he wants to show how the social environment of an individual and the activity of the individuals who are part of it can become synergistic or destructive. We have already seen that an individual under stress can no longer make sound decisions, and he wastes his metabolic resources. To treat this individual, his environment must also be restabilized, or he must be assisted in finding a more supportive environment. In “L’homme imaginant” (1970) (literally: “man while he imagines”), Laborit’s wording is close to the analysis of Stalin’s regime by Reich.82 Both think that a stressful environment can pollute its subsystems and the systems that contain them. It can go both ways. Thus human societies can pollute nature and the tissues of individual organisms, and this pollution is then maintained by these polluted subsystems. This idea is often developed in systems theory when it assumes that to repair a system one needs to coordinate top-down strategies (working on the globality of the system to repair local damage) with bottom-up strategies (working on a local mechanisms that can influence global dynamics).83

CYBERNETICS AND THE SYSTEM OF REGULATION

Systems thinking was defined when thinkers like Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1950, 1968a, 1968b) and Norbert Wiener (1948) created a rigorous model for the notions of system and of regulation. Laborit is one of those who introduced this way of thinking in France.

Ascending and Descending Causal Chains. In the example of the rapport between the membrane’s pump and the internal environment, there is a constant oscillation between the concentration of sodium around the cell and in the cell. These variations are due to three factors at least:84

The environment imposes some conditions on the organism; the organism has its own proper conditions for its existence. These two types of conditions create a vital dialogue between the metabolic demands and what the environment has to offer. Take the example of temperature. If the basal milieu of the human organism is not 36°C (98.6°F), the organism can die. The environment of the planet follows dynamics that do not take this exigency into account.

Temperature activates a “descending” causal chain that has influenced the mechanisms of evolution (only that which can live in an existing geographic system survives), and all of the organism’s levels of organization. This influence is going to be countered by a series of local “ascending” reactions, which regroup themselves to adapt, more or less effectively, to what the planet offers. This ascending chain was constructed, mostly phylogenetically, to protect the exigencies of the internal environment. We now know that these bottom/up demands can influence the planetary system.

Psyche and Organism in Biology. Laborit does not spend much time situating the psyche in his model because it is not a topic that he studied.85 However, he needs to situate psychological dynamics in his general system. He situates them in a particularly complex part of the organizational system of the organism. In the previous section, we have determined the necessity to coordinate two axes:

The psyche is situated somewhere at the intersection of these two axes. It participates in the mechanisms that coordinate the inside and outside of the global organism with the demands the ascending and descending chains impose on behavior.

To negotiate with the environment, the complex organisms create a social milieu as an intermediary between the organism and the environment presented by the planet. The more this social environment becomes complex, the more the propensities of the organism mobilize the dynamics of the psyche. Indeed, even before considering language, socialization requires that the members of the species have come to a certain agreement concerning what is perceived and on the correlation between a stimulus and behaviors. With ants, most of the individuals react to a stimulus just about the same way. A certain variation already exists because the conformity is different for each “caste” (worker, soldier, queen). It would seem that the development of the psyche allowed for the appearance of socialized species that attempt, with more or less success, to combine cohesion and diversity. The more the mind can intervene in a complex way into the regulation of the organism, the more the species is able to develop a capacity to combine cohesion and diversity. The need to develop a wide variety of individual particularities can be included in such a point of view.

The Servomechanisms of Stress. Laborit often takes the thermostat as a simple example of a servomechanism. The thermostat makes it possible for an operator to set a goal for a system. Thus, we use a thermostat to regulate the heating system in a building: to set a target temperature. Take the case of a consumer who regulates his thermostat so that an apartment is always at 20°C. The thermostat activates the heating system for as long as the temperature of the apartment is lower than the temperature set by the consumer, and it brings the activity of the heating system to a stop when the temperature of the space exceeds the set goal. For example, the thermostat is set to engage the heating system as soon as the temperature the apartment falls below 15°C and to shut it off as soon as the temperature in the apartment reaches 25°C. The temperature of the apartment therefore oscillates between those two points. This oscillating regulatory system is characteristic of biological functioning in which a static equilibrium is tantamount to death. Only the inanimate world can follow linear functioning.86 In his discussions with Selye, Laborit distinguished two dimensions:87

In an environment where the axis of stress is activated by a known predator and extinguished by its moving away, the servomechanism of the axis of stress generally functions quite well. We have seen that aggression in humans is often perpetuated by forces that are more difficult to define and localize in time and space. The servomechanism of the axis of stress is too primitive to adapt itself to the details of a situation like mobbing or a tyrannical political regime. For some people, the axis of stress is easily activated, whereas for others it more easily deactivates. Laborit, for example, studied postoperative shock. For certain people, it seems as if the servomechanism of the axis of stress does not detect that the surgery is over and successful. The organism continues to react as if it were still in the operating room.

Even if the mind participates in the dynamics that turn on and shut off the axis of stress, as Lazarus supposed, the connection is manifestly indirect. A relaxation method, psychotherapy, a tranquilizer—all can deactivate an active axis of stress, but none of these strategies work in every case. Laborit assumed that these interventions have an indirect effect. He therefore looked for the specific servomechanism that directly stops the stress reaction. He was convinced that it must be a specific chemical stimulus that can sometimes be activated by one of the interventions I have just mentioned. The relation between deactivation of stress and relaxation, for example, would then be indirect. When relaxation adequately activates the parasympathetic vegetative system, this system puts a certain amount of substances into the circulation of the blood; if the substance is detected by the servomechanism of the axis of stress, it will cut off the systems it controls.

At the time, the available knowledge allowed one to think that such a servomechanism could be situated in the pituitary gland. Laborit looked for a substance that could have such an effect on the pituitary gland. He then analyzed all the hormones produced by the pituitary gland, with the hope that there would be one that deactivates, in a targeted way, the axis of stress. His hunch led him to the discovery of what we today call the neuroleptics. These substances and their derivatives have become one of the principal forms of support that psychiatrists propose to their psychotic patients. This type of intervention permits one to think that one of the mechanisms that activates a psychosis has a particularly low threshold, which puts a more complex version of the axis of stress into play. By inhibiting the substances that activate the physiological dynamics of stress and psychosis, and by raising the values of the servomechanism that activates these states, medication can stop the vicious circle of extremely painful anxiety and hallucinations. This is what neuroleptics do, according to Laborit.

Better to Be a Lout than to Be Resigned. Henri Laborit88 uses a simple controlled experiment to show that in the case of stress, it is better to be aggressive and active than to be resigned. For this research, he uses a theoretical model that has the same structure as the one he used in his research on the necessity to maintain the cells active in a deregulated environment. The basic situation is composed of two rat cages linked by a door. The floor of the cages has a wire mesh on it so that one can pass an electric current through it. Rats receive an electric shock ten minutes a day, but the cages allow Laborit to vary the context in which this is done:

Situation 1. The floor tips when the rat changes cage. The rocking of the floor shuts off the electricity. Every time an electric current passes through the mesh on the floor, the rat feels pain. But the rat quickly discovers that in changing cage, the pain ceases. This is the situation of simple avoidance.

Situation 2. The situation is the same as the preceding one, but a light flickers four seconds before the electric current passes through the mesh on the floor. The rat thus changes cage as soon as he sees the light turn on. This time, there is active avoidance of a painful situation.

Situation 3. The door between the two cages is now closed. The rat can only undergo the pain of the electric shock. The situation is “hopeless.” At first, the rat moves in every direction; then slowly, something will inhibit his will to react, move, and feel. After having lived in this way for a week, the rat has lost weight. He acquires a stable hypertension, which then takes weeks to resolve. The amount of Cortisol in his blood is high. The mucous membranes of the intestines develop ulcers. This state of collapse, contraction, resignation is well known by body psychotherapists who speak of constriction and resignation. Reich,89 for example, describes the reaction of a newborn boy who, after circumcision, can no longer cry and scream, ends up contracting himself and becoming mute. Laborit explains that this pathological state (for the body and mind) can become permanent if the situation remains unbearable. A system of inhibition of action,90 similar to the axis of stress described by Selye, is established.

Situation 4. The situation is the same as the preceding one, except that at the end of a week, the door between the two cages is open. Even though he is now able to change situation, “he will not profit from it and will remain stuck in his inhibition” (Laborit, 1989, X.5, p. 207; translated by Marcel Duclos)

Situation 5. The situation is the same as the preceding one, except that in the electrified cage there are now two rats. In discovering that they cannot flee the pain caused by the electric shock, the will get up on their hind legs, which at least reduces the area of body surface in contact with the electrified floor. They will then fight, up on their hind legs, and attack one other with the upper part of their body. Indirectly, this reaction renders them a service. As each body serves as a support for the other, the rats are able to remain on their back legs much longer. A week later, their bodies are in relatively good shape, and the mechanisms of stress have not been established. This only works if the rats are about of equal strength. This is what often happens in the gang wars of adolescents who live in desperate social situations. In other words, an available aggression makes it possible for them avoid being shut up in a state of resignation.

These experiments suggest a series of measures one can take to help someone who suffers from being in a traumatizing context:

Several recent studies91 confirm that the more a person has an unfavorable position in the social hierarchy, the greater the probability that the axis of stress would be intensely activated. This has been observed in rats, monkeys, and humans. This phenomenon has become sufficiently common for it to become a medical symptom often identified in psychiatry as social anxiety disorder. This body of research demonstrates to what point interactive behaviors can sometimes have a deep impact on affective and metabolic dynamics.

The Methodological Limits of Stress Research. Recent technological developments allow us to gather a considerable amount of information on the functioning of an individual (neurological, metabolic, behavioral, psychiatric, sociological, etc.). However, the statistical methods presently available to organize this data do not allow us to manage as much information as is necessary to understand individuals without generating false results. By “false results,” I mean statistical tests that signal a strong correlation between several sets of data while the research method does not guarantee that this correlation is not due to chance. The crux of the matter is that statistical tests require a large number of subjects to test the impact of only a few variables. The more variables you have, the larger the required number of subjects. Today, technology allows us to gather huge amounts of data on each subject. On the other hand, the expensive machinery used by neurologists only allows them to observe small groups of subjects. Because they are nevertheless understandably eager to explore the information their electronic devices allow them to gather, they collect whatever data they can and then use classical statistics to analyze it. Because they are not always statistically wise, this procedure yields a large number of false results with apparently high statistical significance. There is therefore a lack of adaptation between the current statistical methods and the recent development of technology. The result is that many researchers are showing us that there is probably a great many situations that produce profound stress. We find the same problem with certain research that associates cancer with certain products. The only guarantee against this type of statistical effect is the replication of the experiment by different research groups. The more there is replication, the more the observed result of a particular research study becomes robust.

For example, take the excellent recent research conducted by Karin Roelofs and his team (2009) that observed an intense interaction between the following variables on groups of approximately twenty subjects:

The results indicate that there is probably a strong interaction between these variables. However, the preceding remarks make us cautious. All that we can say about studies of this type is that the researchers would like to show that there is an intimate link between all of the variables that they are able to measure: such is the present-day myth that is in vogue. The whole of body psychotherapy uses an analogous model when it reflects on the functioning of an individual and finds clinical reasons to justify its point of view. The practitioners of body psychotherapy consequently identify this type of research as a proof of the soundness of their point of view. But these research studies prove nothing at the moment. They add one more example that supports the myth of an intimate relationship between the dimensions of the organism and its environment. This example reinforces the body of clinical and experimental data that goes in this direction; but the statistical problems I have indicated do not provide a sufficient basis to allow us to speak of scientific proof. In other words, it is possible that there is actually a convergence between clinical and experimental data. For the moment, this convergence only has the status of an intellectual way of thinking that is relatively robust. I have not, for the time being, found research studies that invalidate this point of view.

The aim of this analysis is to render the psychotherapeutic practitioner attentive to the fact that the press is actually full of alarming articles showing that a particular food, a behavior, or a context considerably increases the probability that the axis of stress will be activated or cancer will develop. Most of these works are interesting but suffer from a lack of adequate replication to become anything more than an observation that presents a question. Above all, I hope this research will motivate mathematicians to develop statistical theories that will permit a more fruitful analysis of the immense pile of data that the new technologies have made possible.92 For the moment, there is such a considerable amount of data that reason often drowns in it all.

The “motivation systems” are networks of specialized nerve cells that have the capacity to synthesize and to release certain transmitters such as dopamine, endogenous opioids and oxytocin. These transmitters, if acting in common, may create a psychological state that we call motivation, vitality or creativity. Dopamine gives us the feeling of energy; the opioids provide that we feel fine while doing something and oxytocin motivates us to do something for or together with people we like. (Joachim Bauer, 2009, “The Brain Transforms Psychology into Biology,” p. 234)

The axis of stress has sometimes been used as a medical tool. In its simplified version it seems to have clear boundaries, forming a well-differentiated subsystem. This simplification was necessary to support the activity of the practitioners who are not researchers. In reality, the axis of stress is not as coherent as it might seem. It remains a good example of how an affective organization can mobilize all the dimensions of the organism for its own purpose. Thus, the dynamics of consciousness are recruited in such a way that they generate a profusion of pessimistic thoughts. When the organism needs to be motivated to run as fast as it can from danger, this may be a useful mood. When the danger persists, pessimism leads to depression. The stressed person believes that they are his thoughts and defends them. He thus defends the perpetuation of his stress. Yet when the stressed response has been deactivated, the person appreciates having another mood. This model can only be confirmed if there exists other affects that have a similar structure because it is rare that biological evolution sustains a mechanism that has only one function. It would be too costly for the organism. Since the 1960s, researchers have shown that the dynamics isolated around the notions of stress and trauma are also mobilized to construct affective systems that support constructive affects. Having discussed the axis of stress, I am now going to talk about the more recent research studies, and consequently less developed ones, on the vegetative management of positive affiliation.

In the 1950s, psychiatrist Seymour Levine (1960) began his research studies on stress using rats. He employed an experimental device common among the behaviorists, which had also inspired Laborit’s research. In a first series of experiments, he studied three types of rats.

This study was conceived to demonstrate that stress, when inflicted at the beginning of life, has a devastating effect on the development of the rats. Levine was surprised to observe that the group that grew up poorly and exhibited worrisome symptoms when they reached adulthood was the third group: the ones that did not receive daily electric shocks nor were placed in the cage for a time each day. The rats of the third group were noticeably less curious and less active.