The following sections are dedicated to some personalities of the psychoanalytic world who are generally quoted as having been the precursors of body psychotherapy.

“The Wednesday group,” established in Vienna in 1902, was the first psychoanalytical association. It was composed of medical generalists, neurologists, and sympathetic intellectuals without any psychotherapeutic ambitions, who came to hold discussions with Freud. In 1906, the group was expanded to form the Psychoanalytical Society of Vienna, under the presidency of Alfred Adler (18701973).

Adler was a medical generalist who thought that a few of his patients could benefit from the psychoanalytic vision, even if they did not need to follow a formal psychotherapy like the one proposed by Freud. When he met Freud to discuss this subject, he already had the desire to widen the spectrum of the interventions inspired by the psychoanalytic approach. Like Freud, Adler thought that the soul1 influences not only behavior but also, sometimes, the physiological mechanisms that create the symptoms that are treated by general medical practitioners. Adler even went so far as to propose that if the thoughts have the power to influence the physiological dynamics, these can also influence the thoughts. He wanted to develop a psychoanalysis in which work on the physiological dimension sometimes permits the treatment of the psyche, and a work on the psyche that can treat somatic problems. Through his consideration of the evolution of biological organisms, he noted that a plant cannot displace itself; that the more an organism is mobile, the more its psyche is complex: “The result is that, in the development of the life of the soul, everything that pertains to movement and everything that can be linked to the difficulties of a simple displacement must be included” (Adler, 1927, 1.1, p. 19; translated by Marcel Duclos).

Alfred Adler pushed the identity body-mind to such an extent that he believed a person who was psychically immature necessarily had immature organs. He deduced from that analysis that only by treating psyche and soma could a physician help a patient become stronger.2

Wilhelm Reich would also describe the individual as a biosystem that influences the psychological (treated in psychotherapy) and somatic (treated in medicine) mechanisms.3 He therefore had to clarify the differences between his approach and that of Adler. During his psychoanalytic period, Reich understood the body and the psyche as two subsystems of the organism that have a mutual dialectic4 rapport that he identifies as antithetic.5 The body and the psyche necessarily mutually influence each other because they are part of the same organism; this does not mean that they function in identical ways. On the other hand, there would be functional identity between physiological and psychological dimensions that are spontaneously related to one another in a healthy organism: the two dimensions collaborate to achieve a common goal. Reich’s commentary on Adler summarizes the position that is the most widespread in body psychotherapy: “While we do take the same problem as our point of departure, namely the purposeful mode of operation of what one calls the ‘total personality and character,’ we nonetheless make use of a fundamentally different theory and method” (Reich, 1949a, VIII. 1, p. 169)

During his psychoanalytic period, Reich did not accept the idea that the dynamics of the psyche and the soma are two faces of the same coin that function in the same way. We have seen how Freud had reflected extensively on the connection between psyche and soma. Like other thinkers, he discovered that it was extremely difficult to define what linked these systems together and what differentiated them. This difficulty, distressing to the specialist, still exists today. This explains why so many thinkers,6 including medical practitioners like Adler and Groddeck, have a problem stopping themselves from using gross simplifications. At the end of his life, Reich returned to his critique of Adler and Groddeck; conceded that there is a “unity of psychic and somatic function” (Reich, 1949a, XIII. 9, p. 340). It is mostly this point of view that was then adopted by the neo-Reichian schools; such is not retained in the options defended in this manual.

Another aspect of Adler’s thought that influenced some movements in body psychotherapy is the idea that the needs of the organism are necessarily in conflict with the social demands, because these two systems defend incompatible interests and procedures. For Adler, this conflict alone sufficed to explain the strong prevalence of neuroses in the human species.7

Sabina Spielrein (1885-1942) was a Russian who studied medicine in Zurich, Switzerland.8 There, she became a psychiatrist after having met Jung. In 1911, she became a psychoanalyst under Freud’s tutelage. She traveled to Germany and then Russia, where she got married. In 1920, she returned to Switzerland, where she founded the Geneva Society of Psychoanalysis. She became a psychologist while working at the Rousseau Institute of Geneva, founded by Édouard Claparède. This institute was renowned for its studies on the psychological development of children. Claparède married Helen Spir, daughter of a Russian philosopher. He was therefore particularly hospitable to Russian psychologists in exile from the new Soviet Union.9

Spielrein psychoanalyzed several members of this institute: not only Claparède but also the young Jean Piaget, who then published articles relating psychoanalysis and the psychology of the child.10 Spielrein’s most representative article of this period shows that the spoken language is composed of verbal and nonverbal signs that frame and nuance the meaning of phrases:

When we adults speak of language, we only think of the content of the word and we do not see the role that the resources drawn from the rhythmic and melodic domain of language can play, even in written texts, such as exclamation points, interrogation marks, etc. These melodic modes of expression are even more at play in conversation. One can add to this a third factor which one could call a visual language, which consists of phenomena such as mimics and gestures. These, as images, can also play a preeminent role in dreams. We should therefore distinguish verbal language from other aspects of language: the melodic language, the visual language (image), the language of actions, etc. (Spielrein, 1920; translated by Marcel Duclos)

Spielrein thus created a bridge between psychoanalysis and nonverbal communication and between the beginnings of the psychoanalysis of children and developmental cognitive psychotherapy. The contacts between child psychoanalysts and cognitive psychologists that she established continued without her. A manifestation of this influence is seen in the way the notion of regulation systems proposed by developmental psychology influenced child psychoanalysis. Only later did the notion of regulation enter the general theory of psychoanalysis. Child psychoanalysis was then in its infancy with the explorations of Hermine Hug von Hugenstein and Anna Freud (daughter of Sigmund Freud).

Spielrein did not do any psychotherapeutic work with children. She studied children at the Jean-Jacques Rousseau Institute with the methods of experimental psychology; she psychoanalyzed adults in her home. Unlike Anna Freud, she did not fall in the trap of reducing nonverbal language to a kind of mechanism of communication that the human inherited from the monkey and which would be more archaic than language. On the contrary, her contact with the psychologists showed her that intelligence needs to pass through gestures to interact with objects and form itself.11

Spielrein returned to Russia in 1923. Vygotsky and Luria, who were part of an eminent school of developmental cognitive psychology in the Soviet Union,12 were on the verge of founding the Russian School of Psychoanalysis.13 Like her, they were synthesizing cognitive psychology, affective psychology, and psychoanalysis in their studies of child development. She brought them much information on the recent development of psychoanalysis and of child psychology in Geneva. Both thinkers played an important role in Vygotsky’s thinking.14

In a 1931 article mentioned by Richebächer (2005), Spielrein describes the following study:

Spielrein asks a hundred children and twenty adults to draw an object. Half of the subjects are able to see what it is that they are creating; while the others draw blind-folded.

Over all, the drawings, made with open eyes, are certainly more precise. But as pertains to the details, Spielrein observes that certain aspects of the object drawn blind-folded are better drawn; as if sight interfered with the memory and the knowledge contained in the gestures.

According to Richebächer,15 Spielrein concluded that there existed a particular link between gesture and speech. She was so impressed by this observation that she recommended that work with blindfolds be integrated into the new pedagogical methods that soviet psychologists such as Vygotsky were trying to establish in Russia. She was convinced that such methods could enhance the development of the mind.

Spielrein’s publications are seldom mentioned. She did not know how to mobilize the means that allow for intellectual success. The value of her ideas did not become evident until a half-century later. Passionate as she was, she nonetheless played the role of a muse for a number of great psychologists and psychoanalysts because she had the knack of finding herself at the intersections crucial to her discipline and she felt the importance of the connections in which she involved herself. She set into motion ideas that psychoanalysts like Jung, Freud, Fenichel, Reich, Vygotsky, and Luria integrated into their thinking.

She was persecuted by Stalinism, which wanted to destroy the Jews, the psychoanalysts, and all “nonconformists.” The Spielreins were related to all three of these categories. It is possible that many of her writings were lost during the chaos caused by the terror that dominated the Soviet Union at that time. Finally, she died, executed by a German army firing squad in 1942.16

Nothing happens to you, and you can do nothing unless a multitude of cells work for you, communicate to you joy or sorrow or every other impression, thinks your thoughts, feels your sensations, regulates your heartbeats, make you breathe, make you live. The mouth that you love is formed of living cells; the hand that you seek or seek to avoid is entirely made up of living cells. Everything that you do, everything that you experience is broken down into an infinite number, a countless number of existences and lives. You have felt it yourself: the contact with another has penetrated out of its flux into your soul and body, this presence, this glance provokes a revolution in your entire being, the sound of but one word has repelled you or brought you peace. But it is not you that this contact, this glance, this sound has touched, but some cells that do not obey your reason, that do with you as it pleased them, that pass a thousand impressions before you, before choosing from among them the one that will affect you. (Georg Groddeck, 1913, Nasamecu, p. 9; translated by Marcel Duclos)

Walter Georg Groddeck (1866-1934) was a practitioner of general medicine who, like Adler, wanted to use the psychoanalytical conceptual framework to create an approach adapted to the needs of his patients. Almost the same age as Freud, Groddeck comes in contact with Freud in the 1920s. It is probably Groddeck who most directly confronted Freud relative to the difficulty of integrating the activity of the body into the dynamics of the psyche. Groddeck admired Freud’s work. He was particularly impressed by the theory of the unconscious in the Second Topography. But as a physician, he maintained the common sense of a generalise For many students of body psychotherapy, he is the gentle grandfather of their discipline.

Groddeck (1923) proposed a “psychosomatic” psychotherapy that approaches the patient in his organismic whole. Humans cannot be divided into separate parts and treated, as often happened in the medical disciplines. He explored many ways to take the needs of the patient into account: considered under the angle of both body and psyche, which Marulla Hauswirth summarizes in this way:

Groddeck allies massage and verbal work. He has developed the notion of body defenses, considering that the tensions at the level of the musculature and the reduction of respiration are the means to repress the psychic content susceptible to act as well at the level of the affects and of the drives than of the thoughts. Moreover, Groddeck laid the bases in favor of a systematic work with the negative transference, and he insisted on the importance of paying attention not only to the explicit content, but also to the form of the expression, of the attitudes and to the body postures as carriers of unconscious messages. (Hauswirth, 2002, 1, p. 180; translated by Marcel Duclos)

Even though Groddeck’s propositions remain inspiring, they did not evolve into a psychotherapeutic technique. On the other hand, they influenced the explorations of Ferenczi, Fenichel, Braatoy, and Reich. Ferenczi and Freud regularly corresponded with him. A discussion of his work is always part of training in body psychotherapy. His first work, Nasamecu or “Nature Heals,” published in 1913, is a title that easily relates to the themes developed by the Idealistic methods of body psychotherapy, in spite of a few eugenistic developments.17 Wilhelm Reich always acknowledged Groddeck’s contribution to his thinking. He associates Groddeck’s formulations with Adler’s, that is, with one of a generalist who does not sufficiently differentiate the functioning of the body and the psyche. Reich thought that the Groddeck’s formulations reinforced a psychoanalytical tendency toward the “psychologizing of the somatic”:18

It culminated in unscientific psychologistic interpretations of bodily processes with the aid of the theory of the unconscious. If, e.g., a woman skipped her menstrual period without being pregnant, this was taken as expressing her aversion for her husband or child. According to this concept, practically all physical diseases were due to unconscious wishes or fears. Thus, one acquired cancer, “in order to . . .;” one perished from tuberculosis because one unconsciously wished to, etc. Peculiarly enough, psychoanalytical experience provided a multitude of observations which seems to confirm this view. The observations were undeniable but critical considerations warned against such conclusions. (Reich, 1940, III.3, p. 33)

Georg Groddeck can be recognized as the first person to have developed an approach that regularly combines bodywork and a psychotherapeutic approach in the same session.19 He especially used different forms of deep massage to influence the system of muscular defense that repressed the expression of emotions. At that time, this way to integrate body and psychotherapy was more widespread than we might think:

In 1931, the 6th congress of the “Common Medical Society for Psychotherapy” met in the German town of Dresden. Its general topic was “treating the soul from the body.” The famous Psychiatrist, Ernst Kretschmer, was the chair of this congress. Psychoanalysts Gustav R. Heyer20 spoke on “Treating the Psyche starting from the Body” and suggested to include gymnastics, sports, breath work and massage into the psychotherapeutic treatment. Other speakers claimed to see psychic as well as somatic phenomena as functions of the entire organism.21 One speaker went so far as to state that a combined body-mind-therapy would be the future of psychotherapy. Georg Groddeck gave a presentation on “Massage and Psychotherapy,”22 which is, according to George Downing, one of his finest papers.23(Geuter etal., 2010)

Since then, some body psychotherapists use deep massage in a more systematic way, like those who use the massages of Aadel Bulow-Hansen, Gerda Boyesen, or Ida Rolf.24

Ferenczi’s scientific achievement is impressive above all from its many-sidedness. (Sigmund Freud, 1923b, Dr. Sandor Ferenczi, p. 268)

Sándor Ferenczi (1873-1933) was, at the same time, one of Freud’s close associates and a person who never ceased seeking ways to improve psychoanalysis.25 His research was as much due to an insatiable imagination and curiosity than a difficulty in tolerating constraints and limits. Ferenczi still inspires a number of psychotherapists, but his difficulty in respecting boundaries sometimes renders his arguments questionable. He had as patients a mother and her daughter, and he fell in love with both of them. Freud was never able to have confidence in him on boundary issues (Haynal, 1987; Haynal-Reymond et al., 2005). Nonetheless, up to the end of his life, Ferenczi considered Freud his therapist, his friend, and his colleague. His fluid ethics was also what allowed him to become a sort of microscope of the functioning of the psychotherapist and the way he can use his feelings to capture the intimate workings of his patients. Thanks to this capacity to feel what is at play between him and his patients, he became the first prominent expert on transferential dynamics.26

Irritated by the limits of psychoanalysis, Ferenczi explored, in the 1920s, the possibility of using an active psychoanalytic technique.27 Ferenczi did not have enough internal discipline for his project to succeed; others took up his formulations, which became the basis of most psychotherapeutic approaches (the psychotherapy of psychoanalytical inspiration established by Otto Kernberg, Gestalt therapy, Transactional analysis, body psychotherapy, family therapy, etc.). Ferenczi included in his research the considerations of Adler, Spielrein, and Groddeck on the importance of including the body in a more explicit fashion in a psychotherapeutic process. Ferenczi was at the front of the exploration of techniques undertaken by psychoanalysts after World War I.

Ferenczi tried to create methods that permitted him to help people for whom a “classical” psychoanalytical treatment was not sufficiently adapted to the patient’s needs. He set about searching for an active method that permits the analysis not only of the thoughts but also the behaviors. One of the basic ideas of the active technique was that the affects (especially sexual) are situated somewhere between behavior and thoughts. Therefore, they can be influenced by psychological and behavioral exercises.28 This introduces the notion that behaviors and thoughts are distinct systems that interact through intermediary systems (e.g., emotions). The details of the interaction between acts and representations are poorly understood; the psychotherapist notices that they can influence each other in various ways. A person can laugh when she is sad or cry when she is angry. In that example, we observe not only that the connections between behavior and thoughts are multiple but also that there can be a sort of “resonating” effect between these two dimensions of the organism. Consequently, a person is able to dissociate from her sadness by trying to amuse herself without being aware that the expression on her face conveys sadness to others, even when she laughs. If the therapist becomes a mirror that reflects this image of sadness to the patient, he can then promote an awareness that modifies the way the thoughts of the patient approaches this sadness. The active technique is therefore an attempt to analyze the triangle of thought-affect-behavior that structures a therapeutic interaction.29 In the example just given, if the patient becomes aware that she often dissociates from a sad mood by trying to behave as if she were a happy person, the whole of the triangle restructures itself. Thoughts, affects, and behavior then coordinate together differently; other working modes of the organism become possible.

In Freud’s method of analyzing dreams, the patient tell his dream and free associates with the therapist. In the active technique, the therapist extracts from the patient’s preconscious behavior a trait in which he is interested and draws the attention of the patient to this behavior. Then the therapist decides to make of this behavior a central theme of exploration in the course of subsequent sessions. This manifest creativity of the psychotherapist in interaction with the patient characterizes Ferenczi’s active technique. If his basic argumentation always remains pertinent, his way of justifying his technique is less so. He proposes to give the subject certain “permissions,” like the right to extend the session and get up from the divan, and so on. He also gave “prohibitions,” like proposing to one of his patients that she explore what might happen when she prevents herself from crossing her legs during the sessions when it has been her habit to do so.30 This language allowed Ferenczi to act as if his technique were but a variation of the classic psychoanalytic frame.

The following example shows how a memory can be explored using the active technique:

A vignette showing how to self-explore through singing. Ferenczi31 describes a patient with whom he made little progress until the moment when he asked her to sing a melody that she had mentioned in her associations. It took him two sessions before she dares to sing the song while lounging on the divan. At first she was very shy; but Ferenczi persisted in urging her to self-explore while singing the song. Her voice became progressively more at ease. He suggested that she stand and to sing with her body. The patient then remembered that she sang this song with her sister who made gestures that conveyed daring sexually suggestive undertones. During several sessions, Ferenczi invited her to explore what it was that inhibited her from singing this song with her sister’s gestures. The patient eventually sang with delight. In this process, Ferenczi and the patient together became conscious of a whole series of inhibitions that inhibited her capacity to lead a pleasant life. Ferenczi thinks that this content would probably have never appeared if he had followed a classical psychoanalytical approach.

Ferenczi does not explain why he decided to spend so much time on this song. Today, this type of intervention is often used in body psychotherapy. It implies that the therapist has confidence in his non-conscious know-how which permits him to develop “something more than the interpretation” (Haynal, 2001, 9.5, p. 135). The principal justification for what happened with this patient is that this choice facilitated useful discoveries; and that it made the therapeutic sessions more enjoyable, which is never a bad thing. This is a “post-facto” justification. The technical problem is that in acting in this way, the therapist does not have a rational argument to support his intervention. This line of action is not consistent with Ferenczi’s requirement that a therapist should be able to situate his intervention in an explicit technical context.32

In this example, as in many others, we see that Ferenczi’s active method focuses on behavior rather than what I call the body. Here is another example of an active technique that will be developed when psychotherapists are able to use film and videos in psychotherapy.33

A vignette on the beginnings of video analysis. Ferenczi (1921b) discusses a work on the subject of tics written by psychiatrists who do not practice psychoanalysis. He nonetheless cites this example because it illustrates a technique that could be included in his active method. The physicians place the patient in front of a mirror and have him observe his tic while asking him to recount its history. At the same time, they teach the patient exercises that allow for the exploration of different ways of moving the muscles mobilized by the tic. They also ask what is going on when he forces himself to immobilize the particular region of the body under question. Ferenczi used this behavioral method to help his patients become aware of their behavior and of how it interacts with thoughts and affects.

In addition to these behavioral techniques, Ferenczi (1930) takes up the cathartic methods used by Breuer and Freud in the 1890s. He induces intense states of relaxation34 and regression that arouse such powerful emotional discharges that they are also able to carry repressed memories. This emotional experience is profound. It mobilizes the whole organism. The remembering is particularly alive and detailed. The patient gets up feeling healed. From my experience, this result lasts for two or three years at best, and sometimes only a few days. These cathartic experiences are regularly observed in psychotherapy groups. They especially allow a patient to feel that it is possible to transform oneself: to transform one’s habitual mode of functioning.

Ferenczi in the 1920s thought that such experiences could be usefully reintegrated in the psychoanalytical toolbox if they were well framed. He thought especially of certain patients who have already had extensive psychoanalysis but whose treatment is now stagnant. In that case, the cathartic method might make it possible to shed light into the shadowy zones that classical analysis has not been able to illuminate. To induce a catharsis, he suggests that patients relax and let movements come up the same way that they let thoughts emerge. Ferenczi35 therefore speaks of relaxation, but the term is taken very loosely, because he does not use any relaxation techniques. He proposes a form of laissez-faire, of letting come what needs to come. Body psychotherapists know this type of session very well. It unfolds in three stages:

Here are a few examples of what Ferenczi observes by using this technique:

Hysterical body symptoms: paresthesias36 and clearly localized cramps, violent expressive movements evoking small hysterical crises, sudden variations of the state of consciousness, slight vertigo and even loss of consciousness often followed by a retroactive amnesia. In certain cases, these hysterical accesses take on the proportions of a veritable trance state, in which fragments of the past were relived; and therefore, the person of the physician remained the only bridge between the patient and reality. It became possible to ask the patient questions in order to obtain important information concerning the dissociated parts of the patient’s personality. (Ferenczi, 1930, pp. 89–92)

Ferenczi thinks that these states emerge spontaneously, simply because he had authorized such a bodily laissez-faire to exist in a therapeutic frame. He relates this permission with what happens when a physician administers a hypnotic tranquilizer, like sodium pentothal, to a soldier traumatized by combat. The soldier goes through an emotional phase that mobilizes the dimensions of the organism. The patient cries, screams, and feels the need to retell the traumatizing situation, over and over again. During this phase, we often observe intense body reactions, like a muscular tension that takes over the entire body, an arrested breathing, or an opisthotonus crisis (see the Glossary). The psychotherapist sometimes observes the same series of phenomena when a patient relives a childhood trauma. With his neo-cathartic method, Ferenczi evokes these states. This requires that the therapist is able to accept what is happening in those circumstances, explore the material that appears, and avoid the dangers that can arise by mobilizing the intensity of these emotional eruptions.37

Henceforth, this type of observation became current in the framework of different forms of body psychotherapy. Gerda Boyesen38 observed a similar technique when she was having psychotherapy with Ola Raknes, one of Reich’s students. He obtained similar results by saying: “Here, you can do whatever you want. Simply, if you break a window, you will have to pay to have it replaced!” As a therapist she used the following formula: “You can say or do what you want. But you are not obliged to do or say anything at all. Simply, do not withhold any speech or any movement. Tell me if there is something that you want me to do or to say.”391 have often observed how Gerda Boyesen worked, and I have seen her work many times. She knew how to create an atmosphere that permitted the apparently spontaneous emergence of phenomena close to those described by Ferenczi. But I also observed that this type of permission does not have the same impact when it is proposed by a less charismatic psychotherapist. It seems to me that this type of effect is sustained by the rumors that transform some psychotherapists into stars. For example, I achieve such effects when I am presented in a prestigious manner to a training group. On the other hand, I do not have this impact on my regular patients, who have often selected me from a listing in a phone book or from the Internet without knowing anything of my reputation. We are therefore in a situation close to that of hypnosis, where the specific intervention depends on the quality of the general ambience to acquire its effectiveness.

Like Rousseau, Beethoven, and Tolstoy, Wilhelm Reich (1897-1957) was an immense humanist, a charismatic teacher, a virtuoso in his profession, with an inspiring intelligence and a powerful imagination; simultaneously, he could be highly selfish and obnoxious with those that were closest to him. Reich reinforced this image by presenting himself as a solitary genius at war against the stupidity of others. He is generally recognized as the father of body psychotherapy.40 In the following sections, I show that this title is justified if we admit that a father is part of a family and that he does not always agree to have the children that the social dynamics impose on him. We will see, in effect, that after having had a dazzling career as a psychoanalyst, he turned his back on all forms of psychotherapy to develop a new form of therapy that aims not at the psyche but at the organism. If his organismic therapy has nonetheless favored the advent of body psychotherapy such as we know it today, it is because Reich was part of a large and tumultuous family capable of allying itself to his creativity, and then to create different forms of body psychotherapy that emerged during the 1950s. To understand this process, it is also useful to present Otto Fenichel (1897-1946), who is somewhat of a secret and unappreciated uncle of this domain.

When I began to write this book, I had a specific plan in mind. Fenichel was not part of it.41 For me, he was a boring orthodox Freudian who had been one of the principal references on the psychoanalytical techniques for many generations of psychoanalysts.42 He would have done everything possible to have Reich expelled from the International Association of Psychoanalysis by spreading the word that he was psychotic. Such was his reputation in the Reichian literature. Yet the more that I read the writings of those who were part of Reich’s entourage, the more I encountered Fenichel’s name without knowing why. I therefore set about to inform myself more precisely about him. After some research, I discovered that he had played a central role in the birth of body psychotherapy. This function of uncle was obscured by the Reichians and Freudians for reasons that will gradually become evident.

Fenichel was born in 1897 of a Jewish family of lawyers in Vienna.43 His health prohibited him from becoming a soldier. He enrolled in the school of medicine in 1915.

Like many students of his generation, Fenichel regularly frequented the youth movements. It must be said that the communist propaganda of the period attracted numerous people who had been disillusioned by the war. Ever since the Jugendstil and the Wandervogel (the migrating birds) at the start of the century,44 these movements had multiplied. All of the political parties (from the extreme left to the extreme right), the religious groups (Catholics, Jews, and Protestants), and the ideological movements had their youth movements. Fenichel was close to the Jewish youth movement of the left. Certain directors of this movement, like Siegfried Bernfeld, became psychoanalysts and created bridges between these movements, especially in the matter of sexual education. Probably because of this influence, Fenichel began to attend seminars given by Freud as early as 1916. He participated regularly in the sessions of the Psychoanalytical Society at the beginning of 1918, during the key period when Freud was creating his Second Topography.

The youth from the left denounced an antisexual morality that prohibited adolescents from obtaining a responsible attitude in sexual matters. These movements wanted an education that integrated their need to be sexually informed, supported their right to be sexual human beings, and protected them from perversions in which some forces close to prostitution wanted them to succumb. In this context, the young Fenichel approached the theme of sexual education, especially in Max Hodann’s journal,45 which also enthusiastically welcomed (10 years later) Reich’s Sex-Pol initiative. Fenichel frequented the animated gatherings by Alfred Kurella,46 who related communist thinking, heterosexual Platonic Idealism, and sexual revolution. Kurella defended “a sexual mysticism or Korperseele [the enfleshed spirit] in Vienna and Berlin” (Russel Jacoby, 1983, 2, p. 71f; translated from the French by Marcel Duclos). This branch of the youth movement defended a moral brand of free love and sexual emancipation. The sexual contact of the “new man” necessarily implies the union of souls as well as that of bodies.

In the momentum inspired by his discovery of the youth movements and psychoanalytic thought, between 1919 and 1921 Fenichel proposed a seminar on sexuality, which he opened in the Faculty of Medicine. At the same time, he underwent analysis with Paul Federn, who was a socialist psychoanalyst close to Freud.

Wilhelm Reich was born in 1897 of a Jewish family of landowners in Galicia, in Ukraine, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire before World War I. When he was 13, his mother committed suicide. This event affected him profoundly.47 After completing school in 1915, he became a soldier in the Austrian army during World War I. Lenin’s takeover of power is considered by many Europeans the triumph of liberty over tyranny. The Treaty of Versailles dismantled the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Hungary and Czechoslovakia became independent, and Galicia was annexed by Poland. Henceforth, Vienna was but the immense capital of a small country. Former combatants were allowed to try to pass their medical exams in four years. Reich brilliantly undertook this accelerated formation after he completed his military service. The Reich family had lost all of its possessions. In coming to Vienna with his brother, Reich maintained his Austrian nationality, but he had the status of an Austrian of the old colonies. It seems to me, given the choices that he made in his lifetime, that he identified mostly with antebellum Vienna. He felt close to the critical artistic movements like the Jugendstil and the Secession.48 When he later lived in the United States, he gave to his theory of cosmic energy an aesthetic that makes one think of the apparently natural beauty, such as represented by Gustav Klimt, and to a notion of the natural spontaneity of the gesture incarnated by the dance of Isadora Duncan.

At the end of the war, Reich paid little attention to politics because, above all, he had to fight to provide for his and his brother’s needs. He heard about Fenichel’s seminar on sexology and registered for it in 1919.

In this seminar, Fenichel helped him discover the following topics:

In taking this seminar, Reich discovered, with reticence at first, the idea that “sexuality is the center around which gravitates all of social life as well as the spiritual world of the individual” (Reich, 1937, 1.3.1919, p. 109; translated by Marcel Duclos). What Reich discovered in this seminar touched him so deeply that the themes Fenichel conjured up inspired him for the rest of his life.

Reich followed the example of his mentor and became his friend. He started to attend the sessions of the Psychoanalytical Society of Vienna with a passion. Fenichel and Reich became members of the association together in 1920. They were 23 years old. Reich was in two brief psychoanalyses: one with Isodor Isaak Sadger,50 and then with Paul Federn, who had already analyzed Fenichel.51 At that time, Freud did not require that the psychoanalysts had to have been psychoanalyzed before practicing.52 Fenichel often felt like Reich’s protective big brother. He helped Reich integrate himself into the Viennese intelligentsia. After 10 difficult years, Reich entered into the happiest period of his life. Each step became a discovery, a new friendship, a new battle, a new theory. With Fenichel, he joined the group of Marxist psychoanalysts, where they met a large number of individuals who were glad to work with them. In this intellectual breeding ground, they finalized a synthesis relating Marxism, the theses of the youth movement, and psychoanalysis. Always together, they are passionately involved in the promotion of Ferenczi’s active method. Through the intermediary of Fenichel, Reich met Annie Pink, who became his patient, his spouse, and an eminent psychoanalyst of the left.

Annie was the second patient with whom Reich had an affair.53 The set-up was always the same. The two young adults fell in love during the psychotherapy sessions. By mutual consent, they ended their therapeutic contract, and the woman continued her therapy with another analyst. Having behaved in an “ethical and responsible manner,” they can meet as lovers. If this behavior is considered ethical when this way of acting is accidental, it is no longer considered ethical when it occurs regularly, as was the case for Reich. His first relationship of this type occurred with a friend of Annie who died tragically after a botched abortion, probably after having been impregnated by Reich.54 Freud scolded Reich for his recurring affairs with former patients.55 Even so, many analysts of the period had affairs with their patients, like Jung, Gross, and Ferenczi. As if to reassure himself, Reich agreed to marry Annie when she demanded it; he regretted it a few years later. They had two daughters, Eva and Lore. Wilhelm and Annie both had several extramarital affairs but stayed together to care for the children.

Even if both Fenichel and Reich claimed to be communists, they took part in different brands of communism. Reich was mostly interested in the social transformations undertaken by Lenin in the Soviet Union. Fenichel and his colleagues were more sympathetic toward Marxist socialism. Fenichel and Reich spoke very little about communism. Their interest in Marxism was more a hope for change than an understanding of the thinking of Marx and Engel. It appears that they did not read their writings attentively. When Reich became a member of the Communist Party, he started to use all sorts of terms that are part of the jargon of militant communists, without ever giving the impression that he really understood the meaning and implications of the language. However, as we will see, Reich needed the power that can be acquired through the support of a party for his sexual revolution.

In 1922, Fenichel asked Reich to take over the direction of the seminar on sexology and leaves for Berlin.56

WITH ABRAHAM: THE CLUB OF THE YOUNG PSYCHOANALYSTS OF TOMORROW

Karl Abraham was first trained by Bleuer and Jung at the Burghölzli psychiatric hospital in Zurich. His unconditional admiration for Freud created sparks that accentuated the tensions between Freud and Jung. He established a psychoanalytical society in Berlin in 1908. After the war, this society grew rapidly. It was joined by personalities such as Ernst Simmel and Max Eitingon. Simmel had developed, during World War I, interventions of psychoanalytic inspiration for traumatized soldiers. Eitingon was a Russian millionaire who had trained in Psychoanalysis with Freud in Vienna, Ferenczi in Budapest, and Jung in Zurich. Eitingon decided to sponsor a psychoanalytical clinic with the support of Simmel and the protective sympathy of Abraham. It was asked of each practitioner to contribute to the existence of the clinic, either by seeing a patient free for a year, or by giving 4 percent of the income from one’s practice.57 The treatments in the clinic were often free. Patients were asked to pay what they could if they were not poor. A section of this clinic, directed by Melanie Klein, treated children.58

The project worked so well that Abraham and his colleagues were overwhelmed by the demand for training others in analysis. “Many came to Berlin because the Berlin Poliklinik offered the most rigorous and structured education in psychoanalysis in the world” (Makari, 2008, p. 372). In 1923, the Berlin society and clinic decided to establish “a formal teaching institute with clear requirements” (ibid.). The structure of this first training institute has remained, from then on, the reference for other such training programs around the world. Each individual who wanted to become a psychoanalyst in Berlin was required to have taken courses in psychoanalysis, had personal psychoanalysis with a training analyst, and also individual supervision—something that had not been formally required.59 This structured formation quickly attracted candidates, not only from Germany (Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, Edith Jacobson) but also from Austria (Melanie Klein and Helen Deutsch), England (Edward and James Glover), Hungary (Michael Balint, Sandor Rado, and Franz Gabriel Alexander), Norway (Nic Waal and Olga Raknes60), and even the United States (Trygve Braatoy61). All these therapists are discussed today.

The important point here is that Freudians wanted to keep control of their training procedures and refused all advice (from Bleuler, for example) that encouraged them to include their discipline in an academic curriculum.62 This choice was one of the most explosive positions defended by Freud: creating a liberal profession, based on intellectual skills that cannot be acquired in a university.

When Karl Abraham died in 1925, Eitingon and Simmel ensured the continuation of the institute and the outpatient clinic by recruiting the help of some young colleagues, such as Franz Alexander, Sandor Rado, and Karen Horney.63 This movement in psychoanalysis, which then developed in the United States, neglected the First Topography (the conscious/unconscious opposition) and focused on the Second Topography.

OTTO FENICHEL ENCOUNTERS CLARE NATHANSON AND DISCOVERS THE GYMNASTICS OF GINDLER

In 1922, Otto Fenichel left Vienna for this Psychoanalytic Institute.64 He entered into analysis with Sandor Rado. From 1924 onward, he became one of the trainers of the institute.65

Otto Fenichel met a pupil of Elsa Gindler named Clare Nathanson.66 She used Gindler’s method with children who suffered from tuberculosis. According to Clare, a mutual friend introduced them to each other: “I thought, ‘Poor guy, he does not know it is the body!’ And he, of course, thought ‘She does not know it is the mind!’” (C. Fenichel, 1981, p. 6). They fell in love and married. Financially, Otto was doing well. He was able to find an apartment sufficiently large for Clare to be able to conduct Gindler gymnastics classes. They had one daughter, whom they named Hanna.67 During this period, Fenichel began to follow regularly Gindler’s course for men to try to rid himself of the terrible migraines that no physician had been able to cure. The Psychoanalytic Institute and Gindler’s school were only a 10-minute walk from each other.68 Gindler’s courses treated Fenichel’s migraines so well that he became even more interested in her method. He asked Clare to come to the Psychoanalytical Institute to present Gindler’s work. These presentations were followed with open discussions. In 1927, Otto gave a presentation at the institute on the way to integrate certain aspects of Gindler’s work into psychoanalytical thought.69

One of the impacts of these discussions was to further differentiate psyche, physiology, and body. In Vienna, from Freud to Reich, the psychoanalysts did not dare abandon the notion that the psyche is structured by the way it is grounded in the biological dynamics of the drives. This remains true in Berlin, but the discussions concerning Gindler’s work and psychoanalysis made it clearer for the two camps that the work on the body mobilizes different organismic resources than the work on the psyche. From the psyche’s point of view, the world of thoughts is not the same as the one we perceive starting from the body; reciprocally, the world of body sensations is not the same when we start from the psyche or from real movements. It is as if the psyche imposes a view of the body to function well; the body also imposes a view of the psyche to function well. The same goes for the drives. Different aspects of a drive are mobilized when they are coordinated with the psyche, behavior, or the body. This understanding has clear implications in a practice. According to Fenichel and Gindler, the two approaches can help a person through different means that have a different type of impact. However, each approach has limits and areas of fuzziness. Using both approaches in a single session could increase the area of confusion and diminish the impact each discipline can provide. This practical point of view became clear for Fenichel and for Gindler, who, it seems, never changed their minds thereafter.

On the theoretical plane, these considerations are more difficult to define because clearly the same psyche perceives everything that happens. We had to wait for the modular models to understand that the psyche is a subentity of the organism, and that, like the organism, the psyche is composed of millions of modules that can relate in thousands of ways, in function of the dynamics mobilized in the organism. It is therefore possible that it is not the same organization of the psyche’s modules that emerges at the occasion of an introspection that aims at thoughts or at the occasion of an introspection that aims at the coordination between movements and respiration. If this is true, then the mind does not function in exactly the same way during a gymnastic course or during a psychotherapy session.

“The ego is first and foremost a body-ego,” says Freud in The Ego and the Id. And he means by this that the distinction between ego and non-ego is first learned by the infant in the discovery of its body in such a way that in its world of ideas its own body begins to be set off from the rest of the environment. (Fenichel, 1938, The Drive to Amass Wealth, p. 97)

The epigraph indicates the intellectual environment Fenichel entered when he arrived in Berlin: a refined psychoanalysis about which he was passionate and a gymnast who obliged him to reflect on the contributions of body techniques and their impact on the psyche.

In an unpublished manuscript dating from 1926,70 Fenichel takes up the possibility of relating gymnastics and psychoanalysis. In 1927, he revealed his thoughts on the subject at the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute. He proposed a first synthesis of his thoughts on the body and psyche in an article published in 1928, titled “The Libidinization of the Organs.” Fenichel preferred this wording, used by Freud,71 to that of psychosomatic or body-mind. According to this article, the psychological defense system also regulates the way the libido is connected to the physiological regulations. Like almost all of the male physicians of that generation, he mentions neither the nonacademics nor the women who inspired and influenced him (Clare Fenichel and Gindler are not even mentioned in a footnote). He wrote the article as if his thought was a personal discovery, established on academic and psychoanalytic literature. Clearly, well before Reich’s arrival in Berlin, the future founders of psychosomatic psychoanalysis, like Rado and Alexander, began to think about the coordination of psychoanalysis, the body, and physiology. I emphasize this because at the end of his life, Reich claimed that all of his Berlin colleagues would have learned everything in this domain from him.

Already at this time, Fenichel intuitively distinguished the physiological dimension from the body of the physical therapists. This body, close to that of Gindler, is a coordination of muscle tone, breathing patterns, postural regulations, and the loops of the sensorimotor nervous system. In this sense, it is possible to say that Fenichel initiated a systematic reflection on the way the body dimension participates in the mechanisms that structure the regulatory system of the psyche. Fenichel (1945a, XIII) did not systematically distinguishing body and physiology, as I do in the System of Dimensions of the Organism. For him, body and physiology both make up the world of the organs. However, on the level of technical interventions, each domain is approached differently, and the body dimension is explicitly discussed.

CORPORALITY AND PSYCHODYNAMICS

When in their everyday life they have not focused attention on the condition of their musculature, the latter exists in a state of hypertonus, the degree of which varies with the muscle group and with the individual, and which may occasionally reach complete rigidity. Movements may involve not only unnecessary muscle groups (associated movements), but innervations which are unsuitable and of unnecessary intensity. When in a state of rest, we are sometimes inclined to let certain groups become hypotonic, that is, to have an excessively lowered tension, so that their readiness to function is impeded or weakened. ... In brief, we are dealing here with a defect of varying degree of their “economization and rationalization” of the motor apparatus which is described by Homburger as characteristic of adults. (Fenichel, 1928, “Organ libidinization,” I, p. 128f)72

For Fenichel, once we admit that the psychological resistances simultaneously influence mind and behavior, it becomes necessary to be able to describe how these resistances structure the gestures and postures mobilized by a behavioral style. The association that Ferenczi and Reich made between behavioral style and defense system had a clinical basis. This observation allowed for an explanation by supposing that this connection had a neurological basis, like Pavlov’s conditioned reflexes. But Fenichel was not satisfied with this hypothesis. A behavioral style is often visibly and manifestly influenced by permanent muscular rigidities and sometimes with comical ways of breathing. Specialists in body development show how many children grow up with different forms of scoliosis and lordosis and also respiratory patterns that all gymnastics teachers try to correct. All of this maintains itself “alone” (without permanent interventions by the nervous system) by muscular “dystonia” (hyper- and hypotonus) that have become permanent. Clearly, the neurological and physiological inhibition of movement is based on different mechanisms from those postulated by psychoanalysts for the psychological forms of inhibition.

Muscle tone is influenced not only by the nervous system but also by the quality of the irrigation of the tissues by blood. In becoming rigid, the muscle tissues acquire a particular metabolic quality that will afterward influence the vegetative dynamics and the functioning of the sensorimotor system. It then becomes possible to conceptualize that the defense system which structures the ego is in connection with the systems that structure and inhibit the behavioral repertoire. Fenichel notices that an organism’s dystonia cannot be entirely explained by physiologists who try to explain it according to the quality of nutrition, the quantity of athletic activity, and so on. There are clearly, behind all of this, bodily factors interacting with some mental dynamics that psychoanalysts could study. A polite person uses his muscles and joints differently than a quicktempered person. Fenichel believes that these traits are principally from the character, linked to an individual’s psychic structure. The character, such as defined by Abraham and Reich,73 would then be produced by the interaction between socially constructed bodily practices and the dynamics activated by an organism’s drives.

This is how Fenichel arrived at the proposition that analyzing the dynamics of the body and behavior allows a privileged access to the emotional dynamics that regulate thoughts and behavior. He takes up the thesis well known by all body practitioners—that chronic anxiety influences the muscle tone in a lasting way and lifestyle can generate chronic hyper- and hypotension that can last a lifetime.74 These tensions can also considerably reduce the respiratory repertoire. Thus, many people can only breathe by moving their belly, while others breathe mostly by moving the thorax. These limitations evidently influence the dynamics of the metabolism, which diminishes the energetic resources available to the organism as a whole: motor and behavioral activity, the intensity of experienced affect, and attention.

Fenichel describes patients who tense every muscle in their body to repress an affect that attempts to emerge when the psychological defenses that repress it are dissolving. An example is a patient who complains of feeling nothing but a great void within: her inside was so cramped, her chest and limbs so tense, that they “did not let anything come out” (Fenichel, 1928, p. 131).

THE BODY REGULATORS OF THE PSYCHE

Fenichel’s key idea was that the poorly developed bodies the gymnasts attempted to correct and reeducate were probably full of symptoms that psychoanalysts called neuroses.75 There may be social mechanisms that educate the masses to become easier to handle by creating chronic defense systems that simultaneously structure themselves in the mental and body dimensions of the organism. Around this foundation, the repression of the affects, the reduction of the physiological vitality, and the reduction of the mental imagination can help create behaviors that are compatible with the ideology in power. This key idea for the history of body psychotherapy was set forth by Fenichel as a possibility and then developed by Reich.76

Here is a summary of the arguments expressed by Fenichel in 1928.

PSYCHOANALYSIS AND GYMNASTICS

In the following example, Fenichel describes a psychoanalytic intervention with a patient engaged in gymnastics. The gymnastics teacher83 detects a chronic muscular tension, which is taken up by Fenichel as if it were a symptom produced by Freud’s psychological defense system. He shows that in this case, the psychoanalyst resolves a problem that the gymnastics teacher was not able to resolve. In his article, he does not mention that there were also some problems for which the psychoanalysts had no resolution but teachers of gymnastics could treat. We have already seen such an example: Fenichel’s headaches, which were successfully treated by Gindler, whereas Fenichel had already followed an analysis with one of Freud’s close associates (Federn).

Vignette of a patient who takes gymnastic courses and undergoes psychoanalysis. A patient reported that her gymnastics teacher continually called her attention to the intensity with which she kept her neck and throat musculature in a constant spastic tension. Attempts to loosen this tension only increased it. The analysis showed that as a child the patient saw a pigeon’s head being torn off and the headless pigeon still moving its wings a few feet away. This experience lent her castration complex a lasting form: she had an unconscious fear of being beheaded, and this fear also manifested itself in numerous other symptoms, modes of behavior, and directions of interest. (Fenichel, 1928, I, p. 133)

In this example, the gymnastics teacher detects a bodily manifestation of an unconscious fear with sufficient clarity that this manifestation could become a center around which it is possible to organize the associations of the patient. Because the psychoanalyst respects the observation of the gymnast, he succeeds in following an associative chain that leads her to the repressed traumatic memory. This is a first example of how a gymnast and a psychoanalyst are able to collaborate. In this case, the transferential relationship from the patient to her gymnastics teacher made it impossible to treat her via the body, for the teacher was perceived as the equivalent of the forces that had cut off the head of the pigeon, and the patient identified with the pigeon. Probably in the course of the analysis of this patient, Fenichel discovered that the relation between these forces and the pigeon had been taken as a metaphor of an older problem connected to the relationship between this patient and a member of her family.

Later, Charlotte Selver summarized how a “Gindlerian” therapist would tackle a neurotic trait. As you will see, it is complementary to what Fenichel did with his patient:

The sensory cortex in our brain no only registers sensations as they occur, but is also the storeroom of past impressions, which can be reactivated. The consequence is that a new sensation can be charged with a relation to something perhaps altogether remote. This is the basis of neurotic behavior, and so we sometimes see persons protect themselves from a friendly touch or we see a dog recoil from a friendly greeting. This is a reaction, not to the actual sensation, but to the memory of a cruel experience in the past. So in our work, the mere invitation to quiet is often not enough, and we must devise simple means of inviting sensations in a context of peace and security so that the actual perception may be recognized and distinguished from the irrelevant or neurotic component. (Selver and Brooks, 1980, p. 120)

Fenichel used actual body sensations to find repressed associations, whereas Selver and Gindler taught their pupils to differentiate actual sensations from old associations, and then focus on actual sensations.

After Fenichel’s departure, Reich conducted the seminar on sexuality for one year. After his studies, he launched a career as a psychoanalyst that was as brilliant as that of Fenichel.

To help you understand how Reich’s character was problematic, I propose an imaginary anecdote in which Reich would have become Freud’s housekeeper.

The Freuds look for a new housekeeper for their family apartment and for the apartment above in which Sigmund works. They accept, for a three-month trial period, a Mrs. Reich, who appears competent. The first month, the Freuds are impressed by the meticulous manner with which each corner, each angle, each object in the apartment are impeccably cleaned. They congratulate Mrs. Reich, who begins to grow more confident. While always appreciating the meticulous work of their housekeeper, the Freuds notice that she permits herself to move objects from their original place. Mrs. Reich explains to them that she has taken the liberty to propose certain rearrangements that she finds useful. Certain changes are effectively an improvement with regard to their usual habit of doing things; but the Freuds, without discussing it with her, return some objects to their original places when they do not appreciate Mrs. Reich’s propositions. At the start of the third month, the Freuds leave on vacation. They confide the apartment to Mrs. Reich and ask her to profit from their absence and do a thorough cleaning.

On their return, the Freuds try to imagine what new changes their housekeeper will have made; they chatter pleasantly about it. Upon opening the door, they discover, with fright, what happens when Mrs. Reich’s meticulous creativity is not contained. Everything is impeccably clean and in order, but everything has been changed place. Where there had been a kitchen, there is now a bathroom. The Freuds’ bedroom has become the children’s bedroom, and so on. Mrs. Reich feels proud for having totally rethought the apartment, and to have found a solution for all the inconsistencies she had detected. The Freuds dismiss her on the spot and refuse to pay her for the self-appointed work. They call movers to put everything back in their place but retain, in spite of everything, a few of Mrs. Reich’s propositions.

This anecdote illustrates many of Reich’s striking personality traits. First, there is the rapidity with which he engages himself in a mission and the intensity of his engagement. In his clinical writings, Reich (1927a) identified this type of behavior as impulsive compulsivity. The object of attachment is chosen impulsively, and then totally invested (or overinvested) with all the resources of his genius. Each time Reich focused on an issue, he took on a personal contractual obligation to organize everything his colleagues say and do and create a solution for every existing problem. He did not understand that his colleagues did not always appreciate his propositions. He explained to them what they ought to think and do, but he never negotiated or collaborated with them. He soon discerned resistance, which he always attributed to the defense of questionable personal interests; he was stunned to be finally rejected by the community for whom he had worked so much. The advantage of this strategy has been that of being able to move forward creatively, without being continually held back by the fears and the disagreements of one and all. The disadvantage was to have avoided the collegial discussions necessary for scientific endeavors. This strategy84 led Reich to a dead end on the personal and theoretical plane. His propositions also contained inconsistencies that almost everyone noticed at first glance; he was incapable of integrating these criticisms.

BIOLOGY AND PANTHEISM

There was a domain in medicine about which Reich was passionate and which had nothing to do with what he discovered with Fenichel: the biology that seeks to describe the functioning of the organism.85 Reich was passionate about a theory of evolution that wants to understand the secret forces that animate nature and its creatures. Cellular biology creates the energy of the individual organism: it is a manifestation of the profound forces that animate the universe at the core of the individual. This thinking allowed Reich to shape a deep and imperative need to feel what links him to the forces of nature. He always refused to associate this need to spiritual needs.86 The difficulty for Reich, who was then influenced by a form of diffused Platonism, was to differentiate this profound impression of being animated by nature from the notion of a spiritual quest. The difference between what can be experienced during a meditation session and the impression of being animated by a spirit is always a current topic. Several body psychotherapists influenced by Reich (David Boadella, Gerda Boyesen, Malcolm Brown, or John Pierrakos) took a step in the direction of thinking that Reich’s impression was in fact a spiritual quest that he did not dare name. Personally, I agree with Lowen and Reich that it is not necessary to believe in the existence of a spirit to experience the impression of wholeness that can be felt in meditation. It perhaps consists in a necessary illusion, but not an experiential proof that a spiritual force exists. For Reich and Lowen, the capacity to experience being in communion with the forces of nature is a human capacity that ought to be able to be described in a framework of scientific thought someday.

At the age of 20, Reich did not have the intellectual means to differentiate what he felt from that of a spiritual quest. Wanting to be more Freudian and more Marxist than Fenichel, he could not be anything other than a profound atheist. In the psychotherapeutic milieu, Jung integrates spirituality and the theories of vitalism. However, Jung was the great dissident. The positions that he advocated during the 1930s, close to those of the Nazi Party in some cases, rendered any appearance of sympathy for Jung even more difficult for a member of the leftist group of psychoanalysts. Reich could not express his need of an internal communion with the forces of nature without accepting becoming the worst student in Fenichel’s seminar. On the other hand, biology and the theory of the Freudian libido were, in this context, eminently respectable and legitimate passions.

To try to situate his intimate questions on this issue, Reich published (in 1922) an article in which he renounced his temptation to think like Jung or to adopt the vitalism of Forel and Bergson. This article indicates that he has read these authors with passion, even if he finishes by separating himself from them for the time being. At the same time, he defended the necessity to anchor the libido in the biological thinking of the period. When, in 1934, Reich abandoned psychoanalysis and Marxism, the forces he had built within himself to distinguish his need to unite science and pantheism diminished. Slowly but surely, he began to want to demonstrate that the forces of nature animate each one of us. He then found a thought, near to that of Spinoza, attributing to nature the forces that others associate with a spiritual force, all while remaining resolutely an atheist.

To understand the relationship that Reich establishes with the forces of nature during his studies, it is useful to recall the dominant view in medicine and biology at the time. I summarize a few notions (described in greater detail in the sections devoted to the biologists) to show which aspects of this thinking influenced the young Reich.

THE NOTION OF ORGANISM AMONG THE VIENNESE BIOLOGISTS

During evolution, approach and withdrawal emerged from the general capacity to move. The different emotions then differentiated out from approach and withdrawal. Bodily concepts and then, progressively, language evolved from this movement base (Daniel Stern, 2010, Forms of Vitality, 1.2, p. 20)

It is useful to recall that genetics was founded in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Johann Gregor Mendel (1822-1884). He was a Catholic monk. Like Darwin, who was an Anglican priest, Mendel became a genius of an amateur biologist. He conducted research on the reproduction of small peas, which led him to think that there existed, in every organism, genes capable of mutation that permitted the transmission of the basic characteristics of an organism from one generation to another. He published a first series of the laws of genetics in 1865 in Vienna, during the period when the English were discovering the thought of Darwin and Wallace. As I have already indicated, only after World War I did biologists began to create a synthesis of the two movements, which became the modern Darwinism. If the English integrated genetics with Darwinism, the Austrians of the time integrated Darwinism to the research inspired by Mendel. There was, therefore, in the Vienna of the day, an important and lively movement in biological research that also had a great influence in the German universities. These discussions fascinated the students of the time, notably Reich.

Darwin’s organism (1871) is more a pile of mechanisms than a coherent whole.87 The biologists of the 1920s preferred to represent the organism as a system that functions as a totality. One way to understand the function of the genes was to suppose that the information they transmit gives a meaning, direction, and coherence to biological evolution, even if their combination follows the laws of chance and necessity. Thus, the cells of the eyes provide for the sensation of seeing red due to the same electromagnetic waves in all of the animal species sensitive to color. This constant would be due to the fact that the same genes regulate the structure of the rods and cones of the retina. While reinforcing a certain coherence of the building that is an organism, the genes also create a kind of flexibility that permits the system to adapt as much as possible to its natural and social environment. Reich (1940, I, p. 77) remained faithful to this global view of the organism.

During his studies, Reich (1940, I, pp. 1–7) was passionately interested in different ways to exploit the notion of organism. With Werden des Organismen (The Becoming of Organisms) by Oscar Hertwig, Reich learned to situate diverse physiological systems and their coordination. Through his writings, Reich discovered a form of biological functionalism that supposes that all that survives has a function. The cell was supposed to have a membrane to better protect itself against external stimuli. The male animals were bigger and stronger than the females, or more beautifully colored, to be more attractive to the females, or they had horns to beat off their rivals. This kind of simplistic finalism, which he associated to certain forms of spirituality like Buddhism and the Anthroposophy of Rudolph Reiner, irritated Reich.88 In reading Philosophie des Organischen (Philosophy of the Organic) by Driesch, Reich became aware of the forces that animate the living world. He pursued this theme with enthusiasm for the theory of vitalism of French philosopher Henri Bergson on the relation between consciousness and the evolution of matter (Matter and Memory, 1896; Time and Free Will: Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness, 1889; and Creative Evolution, 1907).

Another famous Viennese student of this period, Konrad Zacharias Lorenz (1903-1989), was inspired by this approach to understand the motivations of living organisms. He received the Nobel Prize in Medicine with Nikolaas Tinbergen and Karl von Frisch in 1973. All three were rewarded for having contributed to the founding of ethology. The goal of this science is the study of the innate behaviors of the species and the way those behaviors permitted the evolution of communication strategies. This research had begun with the study of animal behavior (communication among bees, graylag geese, and stickleback fish). It consisted of studying the innate behaviors of many species to then be able to discover the laws of the evolution of behaviors, starting with that of unicellular animals and ending up with humans.89 Lorenz was born in Vienna, but he studied medicine in New York and Konigsberg (Germany). Once again, politics made it impossible for Reich and Lorenz to appreciate each other’s discoveries.90 It is possible that Lorenz was not a convinced Nazi, but his biological views were compatible with certain Nazi theses.91

Nevertheless, Reich and Lorenz had common views on certain aspects of evolution theory. For example, they both thought that the amoeba already contained basic sensorimotor mechanisms that were developed by all of the species.92 This mechanism is a perfectly functional coordination of core metabolic requirements, the physiological dynamics of an organism, and the regulation of behavior in function of external variables. Reich and Lorenz thought that the social forces of their time destroyed this deep, natural coordination, because they wanted to use the resources of nature for economic ends. For both of them, this was an unacceptable corruption of natural dynamics. Reich’s Spinozian idealism could never admit that biological activity would be anything but good, coherent, and constructive. For Lorenz, natural selection was a cruel and merciless competition between organisms, but some routes were more humane than others.

BECOMING A SEXOLOGIST

After his studies, Reich established himself as a psychoanalytically oriented sexologist and psychiatrist. Being particularly attracted by the sexual dimension of psychoanalysis, he began by wanting to establish some order in the theory of the libido.93 The libido theory was also the only domain of psychoanalysis that had a deep resonance with his interests for the impact of biological dynamics on the psyche.

The Sexual Behavior of People. Reich had a private practice at the time. With Annie, he participated in the foundation of a clinic called the Psychoanalytic Dispensary. This dispensary, directed by the psychoanalyst Hitschmann, was created in the image of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Clinic.94 Most patients who frequented this dispensary were in need of psychological support, as Freud’s theory foresaw. They often did not have what it takes (not enough time, not enough money, or not the necessary intellectual curiosity) for psychoanalytical treatment.95 Gradually, Reich became the chief of this dispensary. Patients often came to resolve problems tied to sexuality (sexual problems, methods of contraception, etc.). These were the patients who made it possible for Reich to discover the great variety of sexual behaviors among the Viennese, and this was in a time when he was having his first sexual experiences. He observed that most of the individuals he saw had a sexual behavior incompatible with the morality they were attempting to follow. He was no exception. Reich had difficulty reconciling his visits to prostitutes with what he called “the (idealizing) platonic side of my sexuality” (Reich, 1937, p. 61).

With his psychoanalytic patients, he explored, in great detail, how intimate thoughts and sexual behavior are related. For example, he published an article on the way people masturbate and on their fantasies during masturbation. He is astonished to discover the immense variety of practices. His male patients do not necessarily have an erection when they masturbate. Even those who have a regular heterosexual relationship have difficulty representing, in their dreams, a situation in which they are having vaginal intercourse with their fantasized partner.96 In another study on coitus and the sexes, Reich (1922b) (a) noticed that the sexual arousal of men often follows a profile a bit different than that of women, and (b) discerned more problems of impotence in men than frigidity in women.97

The Curve of an Orgasm.

The orgastic excitation takes hold of the whole body and results in lively contractions of the whole body musculature. Self-observations of healthy individuals of both sexes, as well as the analysis of certain disturbances of orgasm, show that we call the release of tension and experience as a motor discharge (descending portion of the orgasm curve) is predominantly the result of a flowing back of the excitation from the genital to the body. This flowing back is experienced as a sudden decrease of the tension. (Reich, 1940, The Function of the Orgasm, IV.3, p.62)

According to Freud, neurosis is nourished by the mobilized sexual energy which the organism fails to express and which is not reabsorbed. Reich attempted to further explain this formula. He asked himself how he might describe what the sexual arousal mobilizes in the organism and how this arousal can express itself in a sufficiently satisfying manner so that there would not be a build-up of a neurosis. The term orgasm therefore designates a sexual behavior that does not leave any sexual stasis.98 For Reich, genital sexuality always includes a capacity to have an orgasm. He distinguished between an organic impotence (frigidity or erectile dysfunction) from an orgastic impotence (the impossibility of achieving a vegetative and affective satisfaction). He ends up with the formula of the orgasm which is composed of three main phases:99

During his Viennese period, it is only when he describes sexual behavior that Reich talks of the body. This body is mostly the visible surface of physiological arousal. It is not yet a distinct dimension of the organism. The interruption of the last two phases of the orgastic reaction can bring about a variety of disagreeable psychophysiological events: palpitations, cardiac irregularities, sweating, back pain, headaches, acute anxiety attacks, general irritability, problems with attention, and so on.103 There is a circular relation between the intensification and the evanescence.

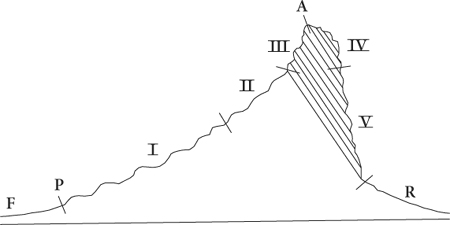

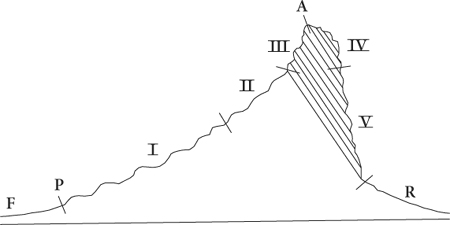

Reich represents the intensity of the sexual charge by a curve that was used by sexologists at the beginning of the twentieth century (see Figure 16.1). He reconstructed with his patients the profile of the curve of a real sexual encounter. The entirety of the curve designates a propension that becomes pleasant in its realization. For Reich, there is no pleasure “that exists here and seeks pleasure there”; but there is a pleasure brought about by the sensorimotor act and that animates this act (Reich, 1940, III.I, p. 24).

FIGURE 16.1. The curve of the orgasm. F: foreplay, P: penetration, I: Voluntary increase of excitation, II: phase of involuntary increase of excitation. III: Sudden ascent to the acme. A: acme. IV: orgasm. The shaded part represents the phase of involuntary body contractions. V: steep “drop” of excitation. R: relaxation (from 5 to 20 minutes). Source: Reich (1940, p. 60).

For Alexander Lowen,106 the description of the orgasm proposed by Reich is relevant but overevaluated in its importance:

Having defined the contours of a particular sexual act in a sketch, it becomes easier to analyze the connection between sexual functioning and certain aspects of the theory of the libido. Reich takes up the theme of the intensity of the thoughts in the same way Hume and Freud do, but he links it more explicitly to the vegetative mobilization of the propension that influence the thoughts. He observes that the sexual fantasies are intense before the climax and tend to become milder with the evanescence. He also notices that when the thoughts linked to the genital sexual act are maintained in the unconscious, the vegetative energy is then diverted toward secondary drives, or even in directions still further away from sexuality. In certain cases, the diversion is so important that problems in the sexual mechanics are observable, such as impotence or frigidity. In this, we find once again the idea that a human propension needs to mobilize a certain type of coordination between psychological and physiological systems to become actualized.107