Body psychotherapists are experts in intra-organismic dynamics. Their publications often include discussions on interpersonal issues in their sessions, but only a few of them have sought to incorporate the issues raised by studies of nonverbal communication. This has slowly changed since the 1990s. An increasing number of body psychotherapists were influenced by systemic therapies and child psychoanalysts who sought ways to incorporate nonconscious processes and nonverbal communication in psychotherapeutic approaches. I present three researchers who have played a key role in this change of perspective. Daniel Stern and Beatrice Beebe are psychoanalysts who have also done a lot of research on mother-infant interaction. Ed Tronick is a researcher, not a psychotherapist, but his studies on mother-infant interaction have had a strong impact on body psychotherapists that have followed this trend.1 Since then, nonverbal communication between adults and in psychotherapy sessions is also discussed by several body psychotherapists (Heller, 1993a).

In the perception of others, my body and the body of others are coupled, as if performing and acting in concert: this behavior that I only can see in others, I somehow embody it at a distance; I make this behavior becoming mine. I take it over and understand it. Inversely, I know that the gestures I myself execute could become object of intention for others. It is the transfer of my intentions into the body of others, and of other’s intentions in to my own body, this alienation of others by me and of me by others that renders possible the perception of others. (Maurice Merleau-Ponty, 1967, Les relations avec autrui chez l’enfant [Relating to Others during Childhood], p. 24; translated in Rochat, 2010)

Resigned and at the end of his life, Reich defended the idea that the only way to stop the education systems from generating malice and violence is to take preventive measures at birth.2

The research enterprises undertaken on the northeastern seaboard of the United States, a region the aging Reich frequented, greatly influenced the new developments in body psychotherapy. These are especially the experimental and clinical research on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) supported by Bessel Van der Kolk in Boston, mentioned earlier, and the research on infants influenced by Daniel Stern in New York and Boston. I now discuss the second trend. Its impact on the body therapies is not one that Reich anticipated, however it does contribute to develop ways of supporting how an infant grows into the realm of social interactions. This research is influenced by a different trend that blends psychoanalysis, developmental psychology, systemics, and neurosciences.

In the sections dedicated to the body in psychoanalysis, I had touched on this theme in mentioning Sabina Spielrein who had combined two topics:

Even though Spielrein had influenced the first attempts to define the individual as the body-mind entity in Psychoanalysis, her contribution in this area is never referred to by Fenichel and Reich, or the founders of child psychoanalysis. Yet her intuitions already announce a tradition that reinforces itself in Psychoanalysis from Anna Freud to Daniel Stern. In Freud’s time, the attempts to include the body by Ferenczi, Groddeck, and especially Reich were considered to be exotic curiosities. However, there was one exception: the Psychoanalysis of the infant. Anna Freud and Melanie Klein developed this field, not together but in a conflictual dialectical relation that became particularly intense in London during World War II. Child psychoanalysis soon developed in a spectacular fashion, thanks to the work of personalities such as Bruno Bettelheim, René Spitz, Margaret Mahler, Françoise Dolto, and several others. It was evident, in that domain, that the interaction with the body and behavior was central because the infant cannot speak.

René Spitz (1965) gave a new impetus to this development by associating clinical psychoanalytic research and the methods of experimental psychology to forge the tools that allow us to better understand and treat infants. Since the work of Bowlby (1969) on attachment, it becomes evident that it was crucial to include the relationship with the mother in all newborn studies. Although the need to include fathers in these studies is discussed, these researchers found it more important to focus on the mother-infant dyad.3 Ainsworth and Brazelton4 reinforce the connection between research, psychoanalysis, and studies on nonverbal communication and attachment theory.

Daniel Stern undertook an immense research study to identify the bases of relational comfort.5 He is the psychoanalyst and researcher in psychology most often quoted in the reunions of body psychotherapists during the last decade of the twentieth century. He ended his career as professor of psychopathology in the Faculty of Psychology and of the Sciences of Education in Geneva, Switzerland.

Stern’s journey often led him to participate in research groups. The principal ones are:

Each one of these authors published important articles and books on the themes developed in the following sections.

The notions of affective attunement and intersubjectivity are most often associated with Daniel Stern by body psychotherapists. To be able to describe what these words refer to, first I explain the notion of contingency such as it is developed in the psychological studies of infancy.6 These notions made it possible to frame targeted research on the way that fine motor practices create nuances in intimate relationships. In the case of Stern,7 it consists in identifying the contour of affective experiences that last but a moment, in which a collection of feelings, a way of using one’s body, and the perception of the movements of the other form a particular experience, “a world in a grain of sand” (Stern, 2004). These experiences often have multiple facets that combine so subtly in so little time that they cannot be apprehended explicitly; when they are, it is inevitably in a very partial way. The nonconscious dimension of these experiences become still more tangible when one analyzes filmed interactions that allow one to perceive the exquisite finesse of how these micro-experiences are coordinated during an interactive sequence, touching deep layers in each of the persons involved. The precision, multiplicity, and rapidity of these interpersonal coordinations, as I have already indicated, cannot be fully appreciated without the help of films, from which we extract coded data. This data are then organized by computer programs, while the researcher remains in contact with the experiential dimension that relate to these motor reactions. The way these body-mind units coordinate with each other makes one think of an invisible waltz, a meticulous choreography that the nonconscious mechanisms easily capture but that remain inaccessible to explicit conscious perception.8

There is contingency when an individual achieves a direct coordination of his gestures with what happens around him.9 Here is the description of an often-used device to study contingency. The leg of a small infant is connected by a string to a tight cord on which are suspended some objects that make noise, like little bells. The researchers consider that the infant has acquired a feeling of contingency when he moves his leg to shake the objects, and that he manages to modulate the noise of the objects by modulating the movements of his leg. For example, this happens when he moves his leg more rapidly to accelerate the rhythm of the ringing, or when he discovers that the greater the movements of his leg, the louder the sounds.

The capacity to control the contingency between his actions and what is going on around him is central, not only to acquire a skill in the handling of objects but also to calibrate the know-how necessary for a constructive communication.10

One of Daniel Stern’s major research preoccupations is to understand how all of this know-how constructs itself, and how it can be repaired when it has not received the necessary support to establish itself. This explains the necessity to intervene directly in the educational systems. An adult is only able to assess the damage and learn how to live better with what he has, while improving as much as possible his communication skills; but he is not able to remember what happened in his first year of life.

The term attunement was a rare word in child psychology until Daniel Stern used it. According to the New Oxford English Dictionary, this term designates what a person does so that others become more aware of what is going on with him. Having said that, there is also an intensification of the quality of the communication, as when two musicians tune their instruments so that they might play together. Stern11 speaks of attunement when a mother accommodates herself to the moods of her baby, calibrating her mental and bodily behavior to support her infant.

This notion of mutual attunement is part of Stern’s attempt to identify how a communication should unfold. It consists of being able to tune the behaviors and the affects of each one by following the rules listed here:

Here is an example of an intermodal interaction of this type:

A ten-month-old girl is seated on the floor facing her mother. She is trying to get a piece of puzzle into the right place. After many failures she finally gets it. She then looks up into her mother’s face with delight and an explosion of enthusiasm. She “opens up her face” [her mouths opens, her eyes widen, her eyebrows rise] and then close back down. The time contour of these changes can be described as a smooth arch [a crescendo, a high point, decrescendo]. At the same time her arms rise and fall at her sides. Mother intones by saying “Yeah” with a pitch line that rises and falls as the volume crescendos and decrescendos. “yeeAAAaahh.” The mother prosodic contour matches the child’s facial-kinetic contour. They also have the same duration. (Stern, 2010, p. 41)

An interesting point in this model is that the goal of such a behavioral attunement is to share an affective dynamic in an interpersonal way. This type of behavior is a way to try to harmonize two souls. Here, Stern distinguishes in a particularly clear manner what is behavioral and what is mental while analyzing how these two dynamics are intertwined: “Affect attunement reflects the mother’s attempt to share the infant’s subjective experience, not his actions. . . . She wants a matching of internal states” (Stern, 2010, p. 114). For Stern (2010, p. 41). The vitality form of his mimics the same one the infant can feel in the verbal response of the mother. These behavioral expressions and the impression that he feels correlate. Stern (2010, p. 46) has found some neurological research that describes nerves capable of reacting to nervous reactions coming from different sensory sources. He also quotes the work of Gallese on the mirror neurons as being a system that allows for the reconstruction in oneself of certain targeted actions made by others (Stern, 2010, p. 46). He concludes that we are not far away from being able to demonstrate that there are multimodal connections in the brain. These are based in primitive circuits that can treat neurological information independently of the complexity of the information conveyed. These circuits could then become more condensed and capable of coordinating heterogeneous systems of information.

This hypothesis, speculative for the moment, could be extended to the notion of the dimensions of the organism to explain how bodily, behavioral, metabolic, and mental dynamics could coordinate around affective dynamics. This is the thesis that Daniel Stern tries to defend in his 2010 book, The Forms of Vitality. He distinguishes the emotional dynamics on the one hand and the dynamics that modulate the vitality of an organism on the other. This hypothesis is close to that of Alexander Lowen (1975).

Intersubjectivity is a need for shared experiences, a desire to be understood and to be able to share experiences with others. Even if it is in fact impossible to share one’s experiences with others, the desire is there, it is innate, and it is powerful.14 It is therefore yet another necessary illusion. This illusion reinforces the need to intensify the exchange of information between two organisms. When this desire constructs itself in a harmonious relationship, it allows each one to better understand oneself and the other. According to Daniel Stern, it is a system of motivation essential for the survival of the species that permits the construction of diverse forms of attachment like those that establish themselves in a love relationship. When a love relationship dies out, the protagonists often discover that the intersubjective impression was mostly an illusion. For example, the parents of a drug-addicted adolescent discover that they never understood him. Most of the time, the extinction of tender feelings and the intersubjective illusion that accompanies it is preceded by a lowering of the intensity of exchanges between the organisms involved.15

Even if intersubjectivity is often associated with Daniel Stern’s work, other researchers, like Andrew Meltzoff and Colwyn Trevarthen, have also developed the notion in an interesting way.16

In 1997, Stern gave an account of what he saw by analyzing, image by image, a boxing match between Mohammed Ali (or Cassius Clay) and Al Mindenberger.17

Vignette on Mohammed Ali. “[Stern] found that 53% of Ali’s jab and 36% of Mindenberger’s jabs were faster than visual reaction time (180 msec). He concludes that a punch is not the stimulus to which the response is a dodge or a block; that we must look beyond the stimulus and a response to larger sequences. Instead it is more reasonable to assume that a punch or a block is a hypothesis-generating or hypothesis-probing attempt by each person to understand and predict the other person’s behavioral sequence in time and space.” (Beebe and Lachmann, 2002, p. 97)

In a brilliant study, Beebe et al. (2008) detail the temporal profile of these non-conscious predictions. She demonstrates that the eagerly awaited behavioral schemas are variations on a theme. The organism awaits not only typical behaviors but also a degree of variety. According to Stern, this type of scenario is established at a “presymbolic” level on a continuum that goes from the reflex to consciousness. This local model implies at least three series of issues:

The more the presymbolic dimension is consciously accepted, the more the protagonists of an interaction can become clear-sighted about what is going on between them. In couples therapy, we often notice that this nonconscious level through which messages are transmitted is poorly integrated in moments of conflict.

Stern’s last work (2010, p. 107) on vitality allows us to synthesize this theme. The dosage between intensity, form, and relevance is important for the psychotherapist. The more intense a gesture, the more life it carries and more it fascinates (a) if it conserves a relevant shape and (b) if it can be received by the surroundings. This is easily visible in the infant. When he has too much vitality, the infant becomes overexcited and chaotic, bothers everyone, is unable to quiet himself down, and almost always ends up crying even if no one is rejecting him. When the parents present too little stimulation, the infant sometimes calms himself or becomes restless because he is lonely. When parents present an intense and chaotic stimulation, the infant goes away from them as far as is possible.19 “Babies learn their own special repertoire of behaviors to regulate stimuli that are too intense. They can simply turn their head away from the stimuli, or they can look straight at you but focus on the horizon. Some babies become experts in suddenly falling asleep” (Stern, 2010, p. 107). One of Stern’s ideas is that the million pieces of information we receive at every instant group themselves around the contour of vitality. These contours coordinate several meanings, several modalities, and several dimensions in each one of us and in our interaction with another. The management of these contours is explored in the arts like music and dance,20 which sometime touch the feelings and thoughts of millions of people in similar ways.

Beatrice Beebe is another psychoanalyst who combines psychoanalytical psychotherapy and research on nonverbal communication. Although she does not present herself as a body psychotherapist, her work explicitly incorporates a systemic approach to interaction and the way an individual behaves. Several body-mind therapists, for a long time, have known about her way of regulating her own behavior and that of her patients. Yet the way Beebe (2004) details the dimensions of the patient’s experiences establishes her firmly in the psychoanalytic tradition. Daniel Stern guided her thesis. She participates in several research centers at Columbia University in New York City, particularly in the Laboratory of the Communication Sciences under the direction of Joseph Jaffe.

At the start of the 1970s, the eclectic body psychotherapist who was interested in the notion of regulation was torn between two basic models:

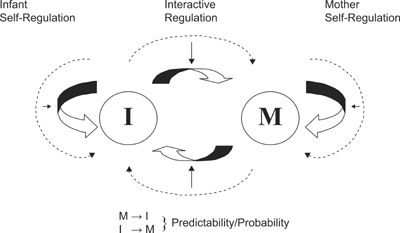

The psychodynamic models of the time focused on the analysis of transferential dynamics that explored an intermediary path that did not allow for a satisfactory distinction and coordination of auto-regulation and interpersonal regulation. Most psychotherapists combine the two dimensions in their practice, and some tried to propose explicit ways to coordinate them.21 To my knowledge, Beebe is the first to integrate these two dimensions explicitly. One of the advantages of her model is that it is based on sophisticated analyses and at the same time comfortably useful in a practice. It is based on the following statistical distinction:

In both cases, the definition of the contingencies necessitates the idea that a behavior can be foreseen. Thus, auto-contingency implies that the advent of a behavior made by one person allows for the anticipation of the probability that another behavior will appear in that person. Similarly, an interpersonal contingency makes it possible to foresee that if a person behaves in one way there is a certain probability that another person will behave in a predictable way in the following minutes. Beebe remarks that a certain degree of foreseeability makes it possible to render a relationship between several persons more comfortable. This is clinically important for the analysis of narcissistic individuals who are proud when they can be as unpredictable as possible, and then lament because they have been rejected.

Beebe’s basic model describes the way interacting individuals auto-regulate, and how these individual processes form the basis from which a relational system emerges.22 The following shapes the psychotherapeutic relationship between a patient and a therapist:

A repertoire is composed of a set of activities that are more or less probable. This probability can vary in function of (a) personal characteristics, (b) the protagonists, (c) the structure of an interaction, and (d) general situations. In a given therapy session, the repertoire of each participant adapts to the particularities of the relationship. Thus, a patient will have a behavior with his therapist that he also has with other persons, but it will undergo some modifications linked to the frame (chair, sofa, etc.) and the therapist. Similarly, the therapist will have a behavior that he also has in his private life and with other patients, but the particularities of the patient will impose some more or less important modifications. Each of the protagonists will notice that he is more or less comfortable, more or less at ease, more or less anxious, more or less confident, and more or less inspired with certain individuals. This varies from one situation to another, but each one’s dreams show that there often exists a series of recurrent expectations. All of these factors influence the quality of a relationship.

Beebe’s diagram (see figure 21.1) illustrates what is happening in all kinds of situations by making each arrow in her schema more or less dense in function of the intensity of the activity they represent. I present three crisis situations to illustrate this analysis.23

FIGURE 21.1. Systems model of interaction. Arrows indicate predictability (“coordination” or “influence”) between partners. Dotted arrows represent the history of the pattern of predictability.

From the moment a system of self-regulation becomes a behavior that can be perceived by others, it acquires an ostentatious status.24 Let us take the case of the newborn infant who touches himself, turns his gaze, reduces his breathing, and arches his back when he is anxious. These behaviors can help him reduce the disagreeable feelings that are overcoming him, but at the same time, they can inform an attentive adult concerning the type of attention that he needs.25 It is not necessary that these behaviors have been activated in order to alert the other.26 These forms of auto-regulation may have been “selected” by evolutionary dynamics because others can perceive them. The response of adults depends on what catches their attention at that moment and the way they manage to integrate this information.

A more detailed example of the way a behavior participates simultaneously in a form of self-regulation and regulation of the other, which Beebe often quotes, is what happens when two people look into each other’s eyes:

These three points are based on observations of the mother-infant relationship made by Daniel Stern (1971, 1977) and Tiffany Field (1981, 1982). Field demonstrates that by avoiding eye contact, the infant automatically reduces his internal tension and cardiac activity. Even if this innate reaction were partially accessible to introspection most of the time, it comes about automatically without any conscious involvement.

Infants interact with mothers, fathers, and others in unique ways that are mutually created as the infant and the individual engage with each other (Tronick, 1989). These interactions and relational knowing are not generalized but remain specific to specific relationships. . . . Thus, on one side, the reiteration of interactions with others leads to learning general ways of being with others (e.g., “baby small talk”); on the other side, it leads to increasingly specific and particular ways to be with different individuals (e.g., “Only we do this together”). (Ed Tronick, 2001, Commentary on Paper by Frank M. Lachmann)

Beebe’s model makes it possible to formulate a series of questions that the practitioner knows well but not always in an explicit way:

The first definition refers to a purely mental propension, whereas the behaviorist proposition seems to include the psychodynamic model. The underlying discussion is how clearly psychological dynamics should be differentiated from those of other organismic dimensions. Those that are close to classical psychoanalysis want to associate the term transference to mental forms of assimilations. They are afraid that in their practice behaviorists may not spend enough time on psychological dynamics. Others stress that regulation systems tend to coordinate the dimensions of the organism and that purely mental transference is rare.

The clinical usefulness of the use of the term contingency for the correlations between self and other can be illustrated with the analysis of individuals who suffered violent sexual trauma in the first years of life:29

Vignette on hyper-contingency and trauma. At the occasion of abuse, a young child undergoes an obligation to be intensely in contingency with the abuser. Every part of his organism is abruptly mobilized by the other. In that case, the abuser does not allow for any kind of auto-regulation. In each abuse, this child develops a greater aversion to contingency. Later, when he wants to establish an affectionate relationship with someone, he will find it difficult to synchronize his behavior with that of others. The difficulty lies in the fact that affection often activates contingent behavior, and this person has become phobic to contingency. Consequently, he becomes incapable of constructing a lasting relationship with others. In this individual’s consciousness, there is no connection between his fear of all kind of attunement and his difficulty in building a loving relationship. The difficulty, in therapy, lies in helping this individual, while helping him self-construct, understand that his trauma has impeded his development of necessary communication skills—something that is difficult to acquire in a few months or even a few years. Even if a certain improvement is possible, some residual damage lasts a lifetime. This is one of the many reasons that sexual abuse during childhood always has devastating consequences. To help an abused person become conscious of his fear of contingency and the connection between contingency and attunement is a way to help him or her assess what can be repaired in the present.30

This analysis partially explains why abused patients find it difficult to work with a psychotherapist who associates empathy with contingent behavior. Once this has been understood one has two possibilities. Refer patients to therapists who do not continuously use contingent behavior with patients, or ask psychotherapists to accommodate their behavior to the patient’s deep needs. Beebe’s studies could help therapists who want to find relevant ways of acquiring the skills that would allow them to follow the second solution without losing their empathy and their need for an intimate self-regulation. This way of associating contingency and abuse is a personal contribution to the discussions of this field (Heller, 2004a). Although I refer to this model several times in the following sections, it is not one that is used by Beebe, Tronick, or Downing.

Beebe and her colleagues noticed that a particularly intense or weak chronic contingency between the behavior of a mother and her child often negatively correlates with the development of the child’s capacity for attachment. They conclude that if a high degree of contingency allows for an important exchange of useful information at the occasion of encountering a stranger, it may also be generated by mistrust and insecurity. An example of this type of annoying behavior is the over contingent behavior of mothers who are constantly afraid of “making a mistake” or of being inadequate.31 A contingency in the “midrange” seems to be, by default,32 the right quantity of contingency for the development of the capacity to communicate (Beebe, 2011; Beebe et al., 2010). It is experienced as part of a predictable and secure environment. Even if Beatrice Beebe does not speak of this, I think that the variability of the amount of contingency is also an important dimension of a relational pattern.

Beebe finally came to the point of regulating the speed of her movements in function of the speed of those of the patient. She accelerates her movements in front of a patient who is chronically placid, or slows her movements in front of a patient who is relatively excited, and notices that this modulation of her behavior often has a useful impact. Here, she takes up a theme that Braatøy had already begun by observing the film of a therapeutic relationship.33 He had noticed the extent to which the effectiveness of the therapist can depend on his capacity to modulate his gestures and needs in function of what is going on for the patient. These aspects of the psychotherapist’s techniques require filming to grasp, acquire, and master the capacity to accommodate his behavior in ways that allows him to tackle clinical issues.

Edward Z. Tronick is a developmental and clinical experimental psychologist who studies the dysfunctions between mothers and young children by using the research tools of nonverbal communication. His observations highlight mechanisms that are often relevant for psychotherapists. He conducts his research principally in the Child Development Unit at Children’s Hospital related to the Faculty of Medicine of Harvard University.

Let me begin with an example of selection from messiness: the infant learning to play peekaboo. The learning of peekaboo emerges through the repetitive operation of coherence on the messiness of the infant’s action, intentions and apprehensions in an incremental bit-by-bit and moment-by moment manner. Initially, the infant makes a large number and variety of behaviors and has lots of varying intentions and apprehensions of what is going on. Most of these actions are unrelated to each other or to the adult’s game playing actions. (Ed Tronick, 2007, The Neurobehavioural and Social-Emotional Development of Infants and Children, 5, 35, p. 493)

Possibly, the influence of Cannon at Harvard partly explains the fact that Tronick (1998) proposes a more “organismic” model of the regulators of the self than do his colleagues Stern, Beebe, and Downing. He is in effect attentive to the fact that when an infant is anxious in front of his mother, it is not only the relational behavior that deregulates but also, often, the whole of the mechanisms of affective and homeostatic regulation of each organism. Tronick does not use the term organism. He prefers to use the expression “individual system” (Tronick, 2007, Introduction, p. 2f) which he includes (as do Stern and Beebe) in a dyadic system. Some researchers avoid the term organism, because it is too often associated with a form of an idealistic holistic approach that assumes that a biological system is necessarily coherent.

Like Spinoza, Tronick34 assumes that when several persons think together, they can process more information than when one is alone. For Tronick, an individual system is mostly regulated by the nonconscious mechanisms that organize themselves in time, in function of practices set in action. It also then consists, like the System of the Dimensions of the Organism, of a systemic genetic model in which time plays a central role. Another point in common between the two models is the way Tronick uses the term messy to indicate an individual system at birth. Even in adulthood, the individual system is never coherent because the contour of the subsystems of the organism is fuzzy. It is exactly this fuzzy aspect of the subsystems that permits the organism to be in the search of ameliorating its mode of adaptation at every moment. To the extent that the organism is not omniscient, it sometime happens that its attempt to adapt ends up by making choices that damage its functioning in a lasting way. Tronick also presumes that there is not only one mind, one consciousness, one memory, or one perception but a conglomeration of mechanisms that are designated by these terms. This position is shared by other Harvard psychologists, such as Jerome Kagan (1998).

THE CREATIVITY OF IMPERFECTION

Genetically, a person born a million years ago is almost the same as one born today. It is possible that individuals who are particularly adapted to survival in a wild natural environment are less well adapted today, while those that could not survive a million years ago can do so in our modern cities. Over a million years, humans were able to acquire a greater variety of survival and reproductive behaviors and create numerous adaptive devices (buildings, medication, etc.). The human individual system is sufficiently flexible and powerful to be able to calibrate itself in the function of interactions that it establishes with its immediate environment. However, even when they emerged, the most elementary survival functions have need of this mutual calibration, which constructs itself between the newborn and its family circle. The flexibility of the human organism has important constraints and limitations that guarantee its survival and a minimum of coherence to its development. Within this framework, the genetic mechanisms already produce an enormous amount of variations, as we see when we compare fingerprints. The research on nonverbal communication arrives at the same conclusion for almost all the behavioral micro-regulators it has analyzed. At birth, the mechanisms capable of calibrating themselves are more numerous than those that will be solicited by the geographic and social environment. Thus, the infantile vocalizations are more varied than those that will be solicited by a language. The innate phonetic capacities that are not used by the environment will disappear after a while.35 This explains why so many adults are incapable of acquiring the accent of a new language they are learning. In other words, in growing up, the organism gets rid of some unemployed innate capacities to be able to focus its resources on what it needs to develop for survival. This stance is different from the Idealistic position, like that of Reich, which assumes that is poorly developed function is a manifestation of a repressed capacity.

In his studies, Tronick tends to focus on the way these choices operate at the core of a mother-child dyad, by distinguishing two factors:

For Tronick, this cycle is one of the bases of the creativity of the dynamics of development. A milieu that is too considerate, that almost totally reduces the moments of inadequate coordination can support synergetic strategies, but it could impede the child’s ability to learn to recognize dysfunctions and acquire the art of repairing them.37

HOMEOSTASIS AND ATTACHMENT

Ed Tronick shows that even the homeostatic mechanisms are dyadic. A nursing infant is not able to provide for himself without the help of his mother. Here we see the limits of a theory based on the notion of the dyad. It is evident that even the mother cannot sufficiently ensure warmth and nourishment for her infant. It seems better to me to situate the interpersonal dimensions of the homeostatic mechanisms in the domain of the external propensities such as they are defined in this volume by Hume, Lamarck, Laborit, and Reich. The heating system that a family uses requires a complex socioeconomic infrastructure.

On the other hand, it is possible to take up Stern’s, Beebe’s, and Tronick’s analyses on the dyads by reminding ourselves that often, for babies, the interface between the organismic propensions and the external propensions has the mother as the intermediary. She is not the center of these regulations but the first relay when the father is often absent. It is therefore possible that the organism of the infant is somewhat conditioned to act as if all of its needs depend on the mother.

From the point of view of my practice, I have been struck by the extent to which an abused child remains dependent on his parents for life. The force of the “addiction” has always impressed me. I have had adult patients in psychotherapy who had been abused as children. They complain unceasingly about their parents, preferring to pay me to verify the harm their parents did to them, instead of allowing me to treat them. As soon as the situation presents itself, they seek signs of their parents’ repentance, affection, and acknowledgment. Even when this parent is dying, they are there to help him and ask for a final sign that he is sorry for what he did. Therefore, it seems to me that it is quite plausible to think that a certain form of addiction to parents would be one of the natural forms of accommodation between children and parents.38

What Laborit and Tronick describe is an association between regulators of the organism and a style of interaction that is set in place in the newborn at birth and probably even before. There would then be a physiologic memory of a state of reference for the systems of regulation of the organism. This state of reference would be felt, from the point of view of consciousness, as a profound affective link that mobilizes a feeling of loyalty. Everything happens as if every loving moment developed in adulthood between one’s spouse and children is necessarily associated to the state of reference. I do not claim that this is an exact description of what happens when the attachment to the parents of one’s early childhood is talked about again in psychotherapy by an adult, but it seems to me we will probably have to go in this direction if we want to explain the dynamics of attachment in the future.

The dynamics of such a state of reference is probably close to imprinting, as observed by Konrad Lorenz at the birth of graylag geese. Breaking out of the egg shell, the gosling attaches itself to the first moving object it sees. There is such a strong imprinting that the gosling continues to maintain the attachment to this object even when they finally meet their biological mother.39

THE CYCLE OF “MISMATCHING” AND REPARATION

Tronick approaches this mother-infant dyad by thinking that the newborn is solely an organization of relatively organized behaviors, and the maternal competencies of the mother are only partially developed when she gives birth to her first child. The challenge for both partners in the dyad is to gradually include, in a messy coordination of two messy systems, increasingly coherent and recognizable patterns. The competence to mother an infant mobilizes innate systems of support that are insufficient to teach the mother “what to do.” This point of departure in the system inevitably leads to numerous moments when mother and infant coordinate poorly, are “mismatched,” and find themselves confused, dysfunctional, and frustrated. Having set this frame, Tronick wants to understand how infants and mothers acquire the ability to coordinate their behavior.40 To understand this, he focuses his attention on moments during which the behavior of the infant and of the mother seem to “match.” Matching is defined and analyzed in two ways (Tronick, 2007,111.15, p. 196):

Simply put, matching describes moments when mother and infant play together in a comfortable way. The apprenticeship of the infant and the mother begins when they become capable of recognizing these moments of relational mismatch and repairing them by establishing greater harmony in their dyadic functioning. The capacity to oscillate between moments of dysfunction and reparation forms one of the nuclei of relational competence that the baby needs to acquire in the first years of life. When the cultural environment does not sustain this type of cycle, the mother’s dysfunction is manifest, and that of the infant is almost guaranteed. These remarks concern the repertoire and the virtuosity of the schemas. It consists, in fact, of knowing if the environment solicits a relevant repertoire of behavior and if it permits the development of a certain virtuosity. The infant may thus calibrate in function of a more or less constructive or destructive environment. Some conducts may develop some constructive attitudes in a destructive situation; others may become destructive in a constructive environment, and so on. The destructive aspects seem mostly to develop when the mother is incapable of tolerating the cycle of mismatching and repair. For example, this is the case of mothers who experienced abuse when they were young, who are so afraid that they will also become a bad mother that they become anxious at the least mismatch and become too nervous to allow the mechanisms of reparation to be set up. The positive note in this analysis is that it is no longer the question of isolating traumatizing acts but situating destructive acts into a general context that more or less profoundly supports the possibility of repairing and discovering states of harmony. Some abusive acts are not susceptible to being entirely repaired; but these acts are, in general, extreme. Sadly, in our species, these extreme acts are not so rare.

HOW TO KNOW WHEN ONE’S BABY NO LONGER WANTS TO SUCKLE

A good example of the notion of matching was given to me in films that Martine Zack had taken in Francis Bresson’s laboratory. I saw them at the occasion of seminars organized by Siegfried Frey (1985) at the “Maison des Sciences de l’Homme,” in Paris. She had filmed nursing mothers. In these films, she sought (among other things) to answer the question: what are the behavioral indicators that permit a mother or a wet nurse to know when a baby no longer desires to suckle?

One of the particularly dramatic dyads presents the following interaction.42

A vignette of nursing. The mother is clearly anxious about her ability to be a “good mother.” Her nursing baby then has the burdensome responsibility to send her reassuring signals. The following example shows what Tronick means by a mismatch, a dyadic relationship that does not become organized. The mother presents a breast to her baby, who sucks with delight. Like many other babies, he pauses, during which he catches his breath and digests. He explores the room with his gaze. He then returns to the breast, looking quite content, to continue to suckle. Yet unexpectedly, in the meantime, the mother concluded that if the nursing baby had so suddenly stopped, it was because he did not like her milk. Offended, she puts away her breast. The baby cries because he cannot find the good breast he was expecting. The mother thinks he is crying because she has bad milk, and she does not know what to do. In such situations the mother despairs, but does not know how to repair.

I often refer to this example to point out the danger of leaving a mother alone with her infant too much. It is possible that this mother would not have become demoralized if she had a companion with her who had already nursed a baby herself. The latter would have been able to explain to this new mother that a nursing baby does not drink all at once; because he has the need to auto-regulate, to digest and to breathe. This is also true for the bottle-fed baby.43

Beebe and her colleagues (2007) proposed a way of describing these types of mothers. She distinguishes the mother who interprets the fact that the nursing baby who avoids looking at her as the proof that he rejects her (these are the dependent mothers) and the mother who interprets the avoidance of looking as proof of her incompetence (the self-critical mothers). You will notice that in both cases, it is not the behavior of the baby that changes the “meaning” of the child’s behavior, but the way in which his behavior is perceived.44 The dependent mother is particularly a person who needs others to auto-regulate her when she experiences negative feelings. The distinction between these two types of mothers is apparently quite small, because in the two cases, there is a lack of confidence in their capacity to become an adequate mother and an excess of aggressiveness (a mixture of annoyance, impatience, discouragement, exasperation, and anxiety that produce ways of acting that are extremely unpleasant for the infant). The clinical difference between these two categories is, on the other hand, evident when we observe the way the behavior of the mother and her infant are coordinated. This coordination structures itself in time in such a complex way that conscious attention is unable to analyze it. But the nonconscious systems of regulation of the protagonists are sensitive to it in a predictable way.45

To study the alternation of the phases of mismatch and repair, Ed Tronick creates an experimental situation called the “still-face paradigm,”46 taken up by several psychologists. In these experimental situations, he films a situation that follows this sequence:47

The following is an example of the kind of disruption observed during the phase of the immobile face.48

Vignette on the situation with the still face. A six-month-old girl pleads with her mother to continue playing the game and then throws the toys at her. She then withdraws. Tronick observes a postural collapse and a state of distress. The child then resumes looking at her mother and becomes active. The two types of behavior alternate, but it moves toward the collapse that leads to a sudden rupture in the rhythmic flow of communication.49

The fact that it only takes two minutes to so visibly destabilize the child shows to what extent a child expects certain forms of interaction as early as the first months of life. Ed Tronick associates these mechanisms to the reactions of abandonment Harlow observed in monkeys and in the orphans observed by Spitz.

NORMAL RELATIONSHIPS

Tronick and his colleagues began by studying the situation of the still face with mothers who have no known psychopathology to understand how these alternations between stress and repair unfold. He noticed that during the immobilization of the mother, the children under the age of one follow the sequence below, which may be repeated many times over.50

Phase 3 has particular importance for Tronick because it is the beginning of a personal and independent connection with the world of objects. In this phase, the child learns to auto-regulate by handling toys. Gradually, if the mother persists in her immobility, the fourth phase will transform itself into first an aggressive phase and then into a phase of resignation that leads to the rupture of the cycle. My hypothesis, based on the analysis of adults, is that the pleasure of interacting with objects is probably one of the practices that support the development of the capacity to dissociate. There is then, between the toys and the infant, the formation of a kind of pleasure distinct from narcissism and from the relationship with another. This form of immediate eroticism with objects and media has animated humans since the invention of tools and of solitary creative activities like painting, reading, and writing. Another example is that of people who prefer to spend time on a computer or a mobile phone than to have direct interactions with people. This mechanism is one of the bases of creativity.

Each phase manifests itself through a repertoire of various conducts (around 300 distinct conducts in each observed phase for 54 children) that increase with the age of the child.51 The phases of destabilization and repair occur repeatedly in a situation where the mother and the child play together with the desire to make each other happy. With children at the age of six months, Tronick and his colleagues observe some micro-phases of repair every three to five seconds.

DYADS WITH DEPRESSIVE MOTHERS

Having observed the way the dialogue organizes itself between children under a year old and their mother who has no known psychopathology, Tronick and his colleagues studied the dyads with depressed mothers. He quotes numerous research studies that demonstrate that depression can have genetic and neurological (especially limbic) causes, or that it can be induced by what occurred in utero. Tronick attempts to describe the disturbances that are added to that during the first year of life.52

Tronick confirms Ellgring’s analysis when he shows that depressive behavior can manifest in different ways by mobilizing diverse body modalities: face, voice, touch, coordination of movements between themselves or with those of others, and so on. In certain cases, depression does not stop a mother from adequately functioning with her nursing infant. Tronick selects three types from a large variety of depressive behaviors:53

When I view films54 of an interaction between a “slowed-down” mother and her nursing baby, I am immediately struck by two things:

Tronick and his colleagues detail the dyadic behaviors that create this impression when the mother is hardly expressive. The numbers given pertain to what is visible when the team films a mother and an infant at play:55

The small amount of time that a stressed infant spends with his toys when his depressed mother is immobilized is an important point for Tronick. There would then be an inhibition of the infant’s capacity to learn to auto-regulate by becoming creative with some objects. These infants sometimes show a developmental delay when they take Piagetian tests on their approach to objects.56 They sometimes become adults who find it difficult to sublimate their anxiety by engaging in some creative activity. These adults, when there is tension in the family, become incapable of doing anything whatsoever, and they auto-regulate with difficulty.57

The type of depression also influences the infants. Thus, with withdrawn mothers, the infants spend more time crying and showing their distress; while the infants of intrusive mothers cry very little, avoid looking at their mother and avoid interacting with her.

The problems of the children of depressed mothers become evident when researchers like Tiffany Field (1995) observe the way they interact with strangers. Because these children are often withdrawn, it is difficult to establish a pleasant and playful contact with them.

This is a good illustration of the idea that a person meets a stranger with the practices at its disposal, and that these practices have multiple impacts that repeat themselves, even in a large variety of situations. With this idea in mind, I analyze the interactive dynamics that develop between my patient and me during the initial sessions.

THE INFANT’S CAPACITY TO “REPAIR” HIS MOTHER

I am now going to summarize an analysis of a case that illustrates the repairing activity of newborns. This case is described by a team of psychiatrists from Heidelberg, who collaborate with George Downing and Ed Tronick.58 They take into their care mothers who have given birth but suffer from a major mental illness that renders them incapable of assuming their maternal functions without a solid institutional support. They use psychotherapeutic intervention techniques and conduct research using videos analysis techniques developed by George Downing (2003), Mechthild Papousek (2000) and Ed Tronick (2003). The case is one of a 39-year-old mother and her fourth child. As their real names cannot be disclosed, they are referred to as Karen and Diana by the authors of this study. This daughter was conceived in a brief encounter.

Karen and Diana. To understand the mother, it is useful to recall the vignette of trauma and hyper-contingency. Karen is one of these abused persons who are phobic of contingency.59 The difficulty for a mother who experiences this type of fear is that a certain contingency is inherent in the affective behavioral dialogue that establishes itself between them. As soon as a tender dialogue sets itself up between the mother and her daughter, the behavioral contingency stimulates memories of past abuse that disorganizes her behavior. This is overwhelmingly painful for Karen, as she has no way to manage these moments of disorganization. Although she wants to create a constructive dialogue with her daughter, the amount of contingency between them is quite low. To protect her 5-month-old daughter from the more impulsive forms of her behavior, she requests help from her psychiatrist.

The video-analysis of Karen and Diana occurred two years after the initial hospitalization. The video recording used for this analysis was 8 minutes long. What follows was observed on a sample of 36 seconds. In viewing the film of the first session, Downing and his colleagues are impressed by the following traits:

Nevertheless, something of the mother’s love seems to have been communicated to her daughter, as Diana seems to be doing well, “at least with respect to basic cognitive and motor development” (Downing et al., 2007, p. 284). While her mother is constantly agitated, expressing her affection and her enormous anxiety, which she attempts to control, Diana remains apparently undisturbed. She spends a lot of time looking at her belt and playing with it. Her movements are slow, as if she were exploring what she is touching. She seems to be so concentrated that she appears to ignore what is going on around her. “She is as if in a different temporal universe, one immune to the fast-moving surrounding events” (Ibid.).

Diana’s Reparative Potential. For a brief instant, her mother comes out of her chaotic cascade of suggestions for their play. She amuses herself in imitating Diana, who is playing with her belt. She then places her right hand near the child’s left hand. Karen’s fingers are resting on her daughter’s chair, a few centimeters away from Diana’s hand. An image-by-image analysis showed that the child reacts in less than a second. With her left hand, with which she was playing with her belt, she takes one of her mother’s fingers. Mother and daughter rest in this way for a second. Then Diana slowly approaches her mother’s right hand. The mother’s movements slow down. Karen and Diana both look toward their joined hands. The mother nonetheless continues to make some abrupt movements of the head and face, but the rest of her body is accommodating to her daughter’s slow pace. She lets her daughter lift her hand, and she slowly brings it to her own little chin, and both of them begin to make an O with their lips.61 The coordination of the lip movements happens in less than a quarter of a second. Diana smiles, her face lights up with pleasure, while she puts her mother’s fingers into her mouth. As Karen’s head “veers to the left her entire face seems to relax. The brow smoothes out, and the muscles around the eyes and those around the mouth ease some of their holding. She appears to be a different person, straightforward and fresh, for a duration of about three quarters of a second” (Downing et al., 2007, p. 286).

Suddenly, the mother returns to her previous chaotic state. She smiles, while saying, “that does not taste good.” In no time at all, the mother begins to move rapidly, and Diana takes her time before concentrating anew on the belt.

Karen and her therapists viewed that moment of peaceful communication several times, wondering how they could gradually become longer:

A parent who was unable to tolerate the intimacy of a direct, unmediated affect exchanges may do better here, at least for a short while. Starting from a mutual focus upon some physical thing . . . the parent may be able to ease into a certain amount of positive affect exchange as well. Such a pathway probably works because it is less threatening: It is more dosed, more gradual, more controllable.

I call this the route through the physical object. (Downing et al., 2007, p. 288)

Karen was able to explore the gestures she observed on the film, and become aware of the deeper emotional issues that generated her chaotic behavior when she tried to play with Diana.

The researchers on infants that I have briefly summarized will appear, for some, far from the practice of individual adult body psychotherapy that is the central interest of this book. Yet they have allowed us to reconsider the strategies used in adult psychotherapy.62 One of the principal contributions of the studies on early infancy is to show that straightaway, children are more active than what researchers such as Piaget had expected.63 The infant already participates in his construction and in modifying the reactions of his parents. Even if several schemas only present themselves in a transitory manner, they already participate in the way the organism calibrates itself by calibrating its environment.

These clinical and experimental studies allow us to describe different kinds of early traumatic forms of interaction that were not available when therapists could only understand childhood through the dreams of adult patients.64 Now that we know how the baby of a depressed mother tends to behave, we are able to reread adult behavior differently and grasp those aspects of behavior that are remnants of their past. A psychotherapist now is able to note that his adult patient “behaves as if he has had an abusive depressed mother.” Or he can notice that the patient “uses types of acceleration of the rhythm of communication described by Beebe.” After an inquiry, the therapist may discover that not only did a patient have an intrusive mother, but his wife is also intrusive. It then becomes possible to reflect in a more precise way on all the practices that structure an individual’s strategies. This coordination of practices often revises itself in time in function of circumstances; but sometimes some practices form a static nucleus around which others organize themselves.

Quite aware that there is insufficient time to analyze the wealth of practices that gather in an organism (there are millions), the body psychotherapist may use, above and beyond his intuition and know-how, the ongoing research to target his attention. To use these studies, it would be useful if the psychotherapists of today and of tomorrow would take up special studies in video analysis to understand what it can teach them.65 Here we arrive at the heart of the justification for including skills on the management of the body and behavior in psychotherapy. As soon as the therapist admits that his object is a system of practices produced by the coordination of several dimensions of the organism, he needs to include in his field some professional knowledge on all the dimensions that participate in the regulation of thoughts, affects, and behavior.

A method of following a practice in body psychotherapy is that developed by Ron Kurtz (1990) called “tracking”: a term that refers to following the tracks of a prey. According to Ogden and colleagues (2006, 9, p. 189f) “tracking refers to the therapist’s ability to closely and unobtrusively observe the unfolding of nonverbal components of the client’s immediate experience.” This technique is designed to follow practices that mobilize several dimensions at the same time (bodily, mental, physiological, etc.) and help the patient become aware of the whole of this experience and its multidimensional contour. The more detailed the description, the more the patient becomes capable of creating co-consciously with the therapist a global and relevant perception of his living experience. It consists of detailing not only the elements of this experience but also of their organization in time, the sequences that can be repeated when the experience is repeated. This analysis of the dynamics of a schema is different from what may be perceived starting from a body reading. Body reading mostly allows for the discovery of what has become encrusted in a lasting and sometimes static way in the structure of the muscular and respiratory tensions on the one hand and in the character on the other.