‘The second town in the kingdom’

The town of Manchester is in the southern district of the Palatine County of Lancaster, or Lancashire, 185 miles northwest of London. It sits at the confluence of the Rivers Irk, Medlock and Irwell. Local historians writing in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries believed that this site was first occupied by the Ancient Britons, five hundred years before the birth of Jesus, but that the foundations of a settlement could be dated to the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43, during which, to defend themselves, the Britons came together and formed ‘a place of tents’ or ‘Mancenion’. The name changed to ‘Mancunium’ at the time of Agricola in AD 79, then, by the medieval period, to ‘Mancestre’, from which, these local sages conclude, the town’s modern name springs.1

Except to the south, where peat or turf can be found, early-nineteenth-century Manchester was surrounded by coal mines, some of them worked since the seventeenth century, on the estates of, among others, the Dukes and Earls of Bridgewater and Balcarres (Haigh Hall) and the Hultons of Hulton Park. The Old Bridge to the northwest of the town, spanning the River Irwell, was the ancient link between Manchester and her sister township of Salford. The nearby River Mersey was one route connecting the citizens and trades of these towns to Liverpool. The Medlock, running into the Irwell to the south, supplied water to the Bridgewater Canal, a superb example of eighteenth-century civil engineering created to ship Lancastrian coal to the remainder of the county and around Great Britain. The Bridgewater Canal had then been extended, by the ‘Ship Canal’, to connect Manchester and its surrounding areas directly to the Irish Sea to the west. By such means, the cotton bales on which the town and county’s textile industry relied, arriving at Liverpool from the plantations of North America, were then delivered to Manchester’s cotton-spinning mills and, beyond, to the factories of Cheshire, Derbyshire and the West Riding of Yorkshire. The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act of 1807 made participating in the trade illegal in the United Kingdom and its colonies, but Britain continued to import the American cotton picked by the descendants of enslaved Africans for decades to come.

Lithograph of Blackfriars Bridge, Manchester, by Henry Gould, 1821.

(Chetham’s Library, Manchester)

In 1801 the combined population of Manchester and Salford, including the conjoined townships of Hulme, Chorlton Row, Ardwick and Cheetham, was calculated as 108,460. Ten years later it was thought that this number had increased by at least twenty thousand, allowing locals to consider Manchester, in population alone, as ‘the second town in the Kingdom’.2 At this time, according to the Manchester historian and journalist Joseph Aston, ‘between one third and one half of the adult population were not native to the town and the whole parish of Manchester by 1811 contained 22,759 inhabited houses, occupied by 28,282 families, of whom 1,110 families are employed in agriculture, the vast majority, that is 25,338 families, in trade, manufactures and commerce, and a final 1,834, Aston declares, ‘not appertaining to an industrious employment’.3 Aston observes that an Act of Parliament, dated 1791, ‘was obtained for the purpose of lighting, watching, and cleaning the town’.4 The first gas lamp was introduced in 1807. By 1816, the town was lit in the winter months by 2,758 lamps while the streets were swept and ‘the soil carried off’ twice a week.

The growth in population can be explained by the expansion of the textile industry. Through the technological innovations of Richard Arkwright, James Hargreaves and Samuel Crompton, the processes of spinning and weaving were centralized within large factories, with an associated expansion of supporting trades such as machine component manufacture. This brought an influx of workers from the outlying areas of Lancashire and the North, and, further still, from Ireland (via Liverpool). In the second half of the eighteenth century, water-powered factories sprang up along the river banks and canal sides of Manchester, such as Thackeray & Whitehead’s Garratt Mill (1760) and David Holt’s works (1785) on the Medlock, and Bank Mill (1782) on the Irwell. However, the irregular nature of water power in Manchester encouraged the mill owners to experiment with a new concept: steam power. The enthusiastic adoption of this technology was the basis of Manchester’s dominance, signalling the step change required for the full transition from market town to industrial capital of ‘Cottonopolis’.5

In 1816, the district of Ancoats, four hundred acres lying within the northeastern region of the town, reflected this significant change in the townscape. One of the oldest and most distinguished buildings in Manchester was Ancoats Hall, a house of late Tudor vintage set within a sizable plot beside the River Medlock, with formal gardens rolling down to the water’s edge. It was described in 1795 as ‘a very ancient building of wood and plaister, but in some parts re-built with brick and stone’.6 By this date the hall, once the residence of the Mosley Lords of the Manor, was occupied by William Rawlinson, ‘an eminent merchant in Manchester’, one of the new-breed citizens of wealth and influence. The hall no doubt maintained an elegant air of antiquity and even tranquillity, in dramatic contrast to the area lying to the west. As described by The Times, the Ancoats district ‘consists of four great streets, Oldham-street, Great Ancoat-street, Great Newton-street, and Swan-street, from which innumerable narrow streets or lanes branch off’.7 Small mills already existed here by the 1790s, including Shooters Brook Mill, Ancoats Lane Mill and Salvin’s Factory, but by 1816 the sheer number, scale and proximity of the new steam-powered mills that were being built here made the area distinctive, even within a rapidly industrializing town like Manchester.8 The network of canals, including the Ashton and Rochdale canals (completed in 1796 and 1804 respectively) with additional smaller offshoots, and the presence of Shooters Brook – a tributary of the Medlock – made it an attractive area for investment and expansion. In the late 1790s two major spinning mills were built near the then incomplete Rochdale canal by Scotsmen James McConnel, John Kennedy and brothers Adam and George Murray. The seven-storey McConnel & Kennedy Mill on Union Street, known as the Old Mill, contained two steam engines of forty and sixty horse-power.9 The partners then built Long Mill next door, completed in 1806, with a forty-five-horse-power steam engine.10 Murrays’ Mill, also on Union Street, was a monumental eight storeys high.

Although the power from water was limited and had, in any case, been usurped by steam, the waterways in Ancoats facilitated the delivery of coal (which powered the engines) and the movement of finished goods. Two of the many coal mines encircling Manchester were located on the northern edge of this area, including the Bradford Colliery. The presence of the factories encouraged the building of associated businesses, workshops and warehouses. The Canal Street Dye Works was built on a branch of the Ashton Canal, while the Soho Foundry (Peel, Williams & Co.), making components for steam engines and boilers amongst other things, was established on Pollard Street, adjoining the Ashton Canal, in about 1810.

According to Joseph Aston, by 1816 Salford and Manchester had, collectively, eighty-two steam-powered spinning factories, mainly found in the Ancoats, Oxford Street, New Cross and Beswick areas.11 These ‘astonishing monuments of human industry’ were so famous that, as Aston continues, ‘it is become a fashion for strangers to visit’.12

The temporary peace in 1814 (prior to Bonaparte’s escape from the island of Elba, which led to the Waterloo campaign) encouraged visitors from mainland Europe to travel to Great Britain to inspect the recent technological developments. Several arrived in Manchester, noting down their impressions of the town in letters, journals and official reports. Johann Georg May, a factory commissioner from Prussia, described England as ‘this land of efficiency’ where ‘there is a superfluity of interesting things to be seen. There is something new to catch the eye in every step that one takes.’13 Manchester, he noted, is ‘known throughout the world as the centre of the cotton industry’. Adjoining each factory, which, by this date, were usually of at least five storeys, ‘there is a great chimney which belches forth black smoke and indicates the presence of the powerful steam engines. The smoke from the chimneys forms a great cloud which can be seen for miles around the town’ and, as a result, the ‘houses have become black’. May also recalled that one of the rivers ‘upon which Manchester stands is so tainted with colouring matter that the water resembles the contents of a dye vat’.14

The Swiss industrialist Hans Caspar Escher, in August 1814, also observed the effects of the pollution created by the textile industry: ‘In Manchester there is no sun and no dust. Here there is always a dense cloud of smoke to cover the sun while the light rain – which seldom lasts all day – turns the dust into a fine paste which makes it unnecessary to polish one’s shoes.’ That aside, he marvelled at the fact that, within a fifteen-minute walk, he had counted over sixty spinning mills. ‘I might have arrived in Egypt since so many factory chimneys… stretched upwards towards the sky like great obelisks.’15 He also noted the tremendous speed at which new factories were being built, observing the construction of one power loom factory measuring about 130 feet in length and fifty feet in width, with a total of six floors. ‘Not a stick of wood’, he declared in awe, ‘is being used in the whole building. All the beams and girders are made of cast iron and are joined together. The pillars are hollow iron columns which can be heated by steam. There are 270 such pillars in this factory.’16

Johann Conrad Fischer, a Swiss inventor and steel manufacturer, first visited Manchester and Salford in the September of 1814. He described the Philips and Lee spinning mill on Chapel Street in Salford as ‘so large that there can be few to equal it in size’.17 Built between 1799 and 1801, the mill was seven storeys high, employed over nine hundred operatives, and was one of the first factories to be heated by steam and lit by gas, the latter installed in 1805.18 The co-owner, George Augustus Lee, had been the manager of Peter Drinkwater’s relatively modest four-storey spinning mill in Auburn Street, Piccadilly (founded in 1789), the first such mill to be built in the centre of Manchester.

Hans Escher, meanwhile, recalled a factory where the manager speaks to his colleagues throughout the site, while sitting in his private office, ‘by means of tubes and he hears their replies by the same means’.19 He continues: ‘The spinning mills are now working until 8 p.m. by (gas)light. Unless one has seen it for oneself it is impossible to imagine how grand is the sight of a big cotton mill when a facade of 256 windows is lit as if the brightest sunshine were streaming through the windows. The light comes from a sort of inflammable air which is conducted all over the building by means of pipes.’20 Further, ‘the Manchester manufacturers are much more advanced than their Glasgow rivals. To reach Manchester standards of efficiency in Swiss factories we should have to sack all our operatives and train up a new generation of apprentices.’21 Escher reflects on the awesome power created by such machines: ‘One shudders when one sees the piston of an engine going up and one realises that a force of 60 to 80 horse power is being generated… A single steam engine frequently operates 40,000 to 50,000 spindles in a mill which has eight or nine floors and 30 windows. In a single street in Manchester there are more spindles than in the whole of Switzerland.’22

The visitors also made observations about the man, woman and even child power that was required to work the machines. Johann May visited Chadwick, Clegg & Co. (two establishments on Oxford Road and 10 Marsden Square) and in one mill he observed a ‘14 horse power steam engine which drove 240 looms, two shearing machines and six sizing machines. One adult worker operated each shearing and sizing machine.’23 May also recorded that to save wages ‘mule jennies have actually been built so that no less than 600 spindles can be operated by one adult and two children. Two mules, each with 300 spindles, face each other. The carriages of these machines are moved in one direction by steam and in the other direction by hand. This is done by an adult worker who stands in between the two mules. Broken threads are repaired by children (piecers) who stand at either end of the mules.’24

The events around 1812, known as the Luddite Revolt, were clearly still uppermost in people’s minds, as Johann Fischer recalled while visiting one mechanical spinning and weaving shed: ‘when one sees these power looms for oneself it is easy to appreciate the bitter feelings of the men who have been thrown out of work (by them). Fifty of these looms – operated by one and the same steam engine – stood in a medium-sized room. Each was no more than about four feet in height, length and width. They were operated by fifteen artisans and one foreman.’25 He recalled that the movement of the shuttle and the passing of the thread into the machine was executed much faster than could be done by hand, therefore improving output. Moreover, as the foreman observed to Fischer, power looms do not get tired in the same way that a handloom weaver does. ‘Consequently the cloth produced by the power loom is more uniform – and therefore of higher quality – than the cloth made by hand.’26 Fischer left Manchester ‘delighted with the new and remarkable things that I had seen’.27

In a report submitted to the House of Commons to support a petition ‘praying for a limitation of the hours of labour in Cotton Mills’ and signed by six thousand factory workers from Manchester and its environs, many of them parents of child workers, the authors draw attention to the fact that by the mid-1810s children of six and seven years of age, and sometimes even as young as five, were employed in the mills. A working day at this time was around fourteen hours, often without a break. In some factories the temperatures reached an unbearable seventy-eight or eighty degrees. In July 1816 John Mitchell, a physician, visited the Methodist Sunday School in Brawley Street, Bank Top, to assess the number of students that were employed in mill work and the state of their health. Of the 818 children present, almost equal numbers of girls and boys, 269 were factory workers and 116 of those were sickly. The general appearance of the factory children was ‘pale and inanimate… There is a very peculiar hoarseness and hollowness of voice… which seems to indicate that the lungs are affected.’28 Thomas Bellot, a Manchester surgeon, attested that it was not uncommon for factory children ‘to be checked in their growth, to become lame and deformed in their legs… and eventually to die of consumption’ as a result of ‘their long confinement in heated and ill-ventilated rooms, and of their being constantly on their legs during their long hours of labour’.29 He also describes the factory workers among the Sunday School children of St John’s district as ‘for the most part, low, slender, and in general much emaciated’.30 All the medical men commenting on the health and appearance of the factory children were struck and, in many cases, openly distressed by the dramatic contrast in the condition of these children and those who worked in other trades. If the children survived, they would continue in the factories as adult workers.

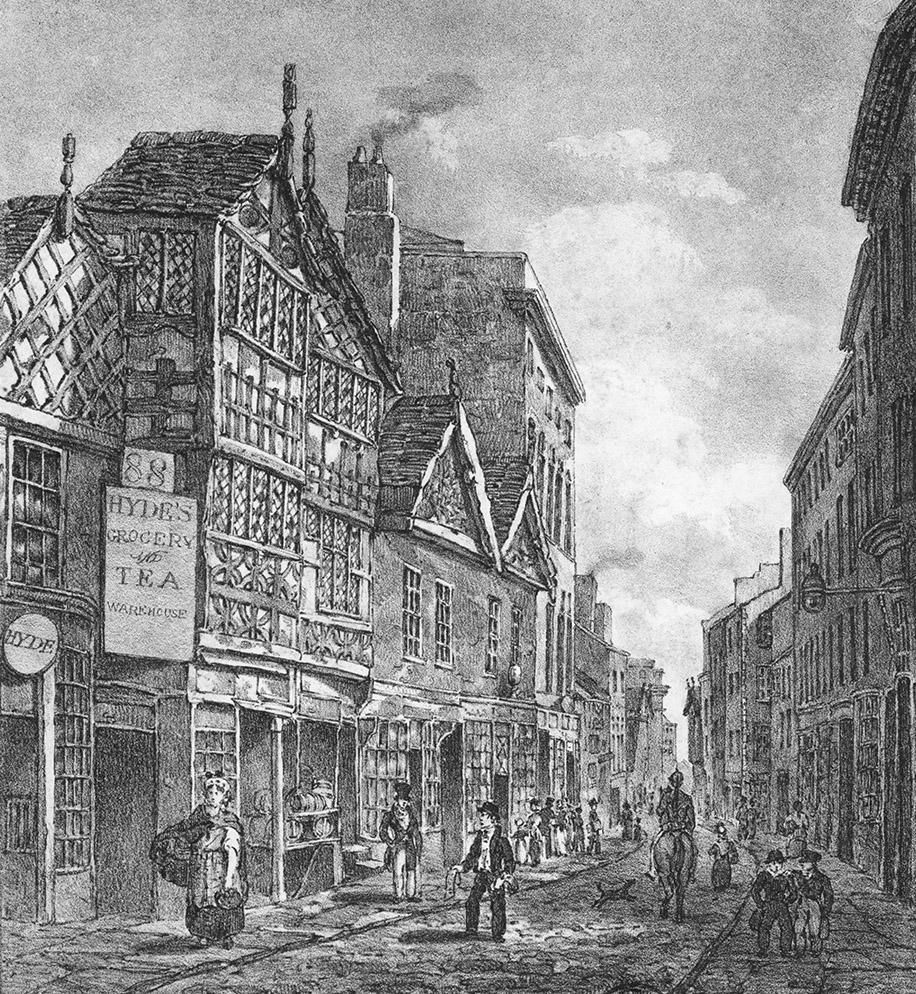

Lithograph of Market Street, Manchester, by Henry Gould, 1821.

(Chetham’s Library, Manchester)

With the factories and associated services came housing.31 The Ancoats area quickly achieved equal distinction, alongside the density and scale of its factories, for its large expanses of terraced houses for the workers. Factory owners tended to house only their key employees, while the average worker lived in housing built by speculators. There were two typical designs. The first model involved two rows of housing back to back, as seen on Portugal Street and Silk Street, and the second consisted of one-up, one-down terraces, literally houses of two storeys with a single room on each. With the back-to-backs, windows and doors were in the front facade, while the rear shared wall was solid, allowing only limited natural light to enter the rooms. Ancoats housing usually had two main floors, although attic workshops also existed. The rapid rise in rents between 1807 and 1815 meant that basements were often let to separate families. To help make ends meet, families or couples often took in lodgers. Housing was, therefore, cheek by jowl, with individual properties crammed with family and strangers. One small benefit of a concentration of workers’ housing within a small area was that the watchmen who patrolled the streets of Manchester at night, would, for a small fee, wake the workers for their daily shifts with a call or a tap on the window.32

The contemporary report in The Times (quoted earlier) also states that Ancoats, ‘created by the success of the cotton-trade’, ‘swarms with inhabitants, who all share its vicissitudes. It is occupied chiefly by spinners, weavers, and Irish of the lowest description, and may be called the St Giles’s of Manchester,’ the last a reference to the notorious slum area in London made famous by William Hogarth’s image of urban horror, Gin Lane (1751). The Times continues: ‘Indeed, no part of the metropolis presents scenes of more squalid wretchedness, or more repulsive depravity, its natural concomitant, than this… its present situation is truly heart-rending and overpowering. The streets are confined and dirty; the houses neglected, and the windows often without glass. Out of these windows, or in the most airy situation, the miserable rags of the family… were hung up to dry.’33 Hans Escher, pondering on the impact of industrialization as it had developed in England, observed: ‘How lucky we are in Switzerland where we have a balance of agriculture and just a little industry. In England a heavy fall in the sale of manufactured goods would have the most frightful consequences. Not one of all the many thousand English factory workers has a square yard of land on which to grow food if he is out of work and draws no wages.’34

From 1810 onwards, male ‘coarse spinners’ (as opposed to fine thread spinners) in Manchester earned between one shilling and eight pence and two shillings and four pence per day, while the women earned between 15s. 7d. and 17s. a year.* Between 1810 and 1816, the best calico weavers’ wages fluctuated from 9s. 6d. to a peak at 13s. 8d. in 1814 and then down to 9s. 2d. The following year they dropped again to 8s. 4d. Calico printers consistently earned £1 6s. a week.35 To put this into context, the average retail price for flour (per twelve-pound weight) was 3s. 9d. in 1810, 4s. 9d. in 1812, falling to 3s. in 1816. Potatoes (per twenty-pound weight) over the same period moved from ten pence to twenty-two pence and down to eleven pence in 1815. The price then fluctuated during the year 1816 between eight and fourteen pence. Irish butter per pound weight dropped from 1s. 1d. in 1810 to 11d. in 1816, while the same weight in cheese stayed at 8½d. until 1816 when it dropped to 6¾d.36

Although the dramatic increase in factory building, and the associated housing for workers, was radically transforming the spread, environment and character of Manchester, there were still areas in the town, particularly around the Collegiate Church (now the cathedral), Hanging Ditch and Chetham’s Hospital (commonly called the College), which, like Ancoats Hall, retained some of their medieval and Tudor appearance. And in addition to factories, the wealth and income derived from the textile industry had funded, throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the construction of many magnificent civic and religious buildings, as well as elegant private houses and squares where the merchants and businessmen resided. In 1814 Hans Escher observed that ‘Everybody who is well off in Manchester has a greenhouse in which he grows considerable quantities of grapes, peaches, etc. These fruits are finer and riper than ours but they do not last so long. The fruit trees in gardens and parks flourish in a remarkable way.’37

The warehouses and offices were located in the centre of the town, around St Ann’s Church (completed in the 1720s) and where the News Room and Library called the Portico (opened in 1805) and the New Exchange (completed a few years later) could also be found. During business hours the town centre, according to May, ‘resembles that of a permanent fair. The warehouses have long windows but they are not high. This is partly due to the window tax and partly because it is convenient to store goods in rooms with low ceilings. Sometimes,’ he continues, ‘when I stopped in the street to find out the name of the firm occupying particular premises I was surrounded by a number of brokers offering twist and calico for sale. The cotton exchange in the market place is very busy.’ He concludes, ‘As in London, so in Manchester it is possible to get the news from all over the world at the exchange. The building is open all day. All the English newspapers and the leading foreign newspapers are available. Visitors are admitted without charge.’38 Other notable buildings in the centre of Manchester included the Theatre Royal, the Assembly Rooms, the Infirmary, the Lunatic Hospital and Asylum, and the Public Baths.39

Building work continued southwards. The foundation stone of St Peter’s Church, built by subscription and located at the lower end of Mosley Street, was laid in 1788. The church was consecrated in 1794. Designed by the renowned architect James Wyatt and built in Runcorn stone in the Doric order, it had the overall appearance of a Grecian temple.40 The altarpiece is recorded as a ‘Descent from the Cross’ by the celebrated late-sixteenth-century Bolognese artist Annibale Carracci.41 The church gave its name to an adjoining area of rough open ground which, by the 1810s, was in the process of being developed but was still used by the locals as a meeting place. Peter Street had been marked out to cross the field from the church towards Deansgate (a main thoroughfare running north to south) in the west. On the north side, on Dickinson Street, the old Quaker or Friends Meeting House was being extended and updated. As described by Joseph Aston: ‘Like the respectable members of the sect which here worship, it is plain, but substantial.’ The building had a burial place attached.42

In 1816, then, the town of Manchester was a visible mix of old and new, standing on the cusp of the full transformation to the industrial city as vividly described by Elizabeth Gaskell and dissected by Friedrich Engels. Although industry had brought riches and employment, there were obvious winners and losers and, in the years following Waterloo, this disparity would become more extreme, feeding an already volatile political and social environment.

* The abbreviation ‘d.’ for a penny derives from the Roman denarius coin, plural denarii. A farthing was one quarter of a penny. There were twelve pence to the shilling, twenty shillings to the pound and twenty-one shillings to the guinea.