‘Hunt and Liberty’

By early 1818 John Bagguley, Samuel Drummond, John Knight and other political prisoners had been released, an indication of the government’s confidence that the repressive measures had been successful. At the same time, Lord Sidmouth introduced a bill to repeal the Suspension of Habeas Corpus Act, as well as a Bill of Indemnity intended to protect ministers from scrutiny once the act was restored.

In February 1818, Richard Carlile published an article in Sherwin’s Weekly Political Register under the headline ‘DISCLOSURE OF THE GOVERNMENT-PLOTS AGAINST THE PEOPLE OF MANCHESTER’, reporting on a petition to the House of Commons from the inhabitants of that town regarding ‘the Meetings of the People and the machinations of Government spies’. It is not, says Carlile, ‘what even the Ministry will be hardy enough to call a Petition from the ignorant or disaffected’; it contains ‘a clear exposure of the falsehoods that have been trumpeted forth by the hireling press, and it sufficiently explains the motives of the Government in not proceeding with the trials of the “Blanketeers”’. The only conspiracy, Carlile concludes, which has ever existed in Manchester or any other part of the country ‘is a conspiracy on the part of the Government to goad the distressed labourers and manufacturers to the commission of acts and outrage, that the former might have an opportunity and excuse for slaughtering the latter through the medium of their soldiers. The Ministers would willingly have butchered one part of the People to have enslaved the other.’1 The Habeas Corpus Act was restored on 10 March 1818.

The new year of 1818 also saw the first issue of a new publication, the Manchester Observer, Or Literary, Commercial and Political Register. While providing the usual material expected of a local newspaper – articles and stories of regional interest as well as reprinting others from around the country, alongside advertisements for local businesses, situations vacant and required – under James Wroe as editor, and his colleagues John Thacker Saxton and John Knight, the paper swiftly became the organ for radical reform in Manchester and the surrounding district. The paper presented ‘To the Public’ its manifesto in its first edition, declaring itself, ‘Free from all party attachments – uninfluenced by names and factions’:

we feel the strongest security for the independency of our political opinions. Others may devote their time and talents to prop the falling fortunes of their favourite party, whether Whig, or Tory; we, however cannot be limited in our support of any portion of our countrymen; our cause is that of the People – our interests are those of the Nation. Happy would it be for our common country, if Britons would for ever abjure all party spirit, and unite in redressing the wrongs which they suffer. If those abuses were removed, which have been gradually introduced into our excellent institutions, neither the people nor the government should have anything to fear; the former would be sured from the encroachments of power, and the latter from the turbulence of anarchy.2

James Wroe was born in Manchester in 1789, that auspicious year, and had established himself as a bookseller in Port Street. By 1818 he had a shop in Great Ancoats Street.3 James Weatherly, a fellow bookseller, recalled in his autobiography that ‘Radical Wroe’ sold ‘Pamphlets and Periodicals’ and that ‘his stock of old Books was of low Priced articles’.4 The role of newspaper editor was a departure from the focus of Wroe’s business to date, but his new publication gave a voice and a champion to the reformers of Manchester and beyond. John Saxton seems to have had a chequered professional history, but one that brought the necessary practical experience to their new venture. In November 1800, on the announcement in the Derby Mercury of his marriage to Susannah, daughter of Mr Hoole of Walton ‘in this county’, Saxton is described as a ‘printer, of Chesterfield’.5 In 1804 he was named on a list of bankrupts as a ‘printer, bookseller, and stationer’.6 He appears on another list of insolvent debtors in 1816, in the Leeds Intelligencer, described as ‘late of Sheffield, Printer’.7 In 1818, no doubt seeking a fresh start, he and his wife, Susannah, had moved to Manchester.8

The Manchester Observer was based at 18 Market Street, a locality later described in The Times as ‘“Sedition corner”… perpetually beset with poor misled creatures, whose appetite for seditious ribaldry, created at first by distress, is whetted by every species of stimulating novelty’. In the same article The Times witheringly dismissed other radical publications, including Black Dwarf, The Medusa and The Gorgon, and those who read them: ‘all the monstrous progeny begotten by disaffection upon ignorance, are heaped on the table or in the windows, with hideous profusion, and the money which should be expended in buying bread for their famishing families is often squandered in the purchase of such pestilent publications.’9 Nevertheless, the Manchester Observer soon established itself as the leading challenge to the authorities and the loyalist press, notably the Manchester Mercury and Manchester Courier. Samuel Bamford not only read the Manchester Observer in the privacy of his own house, but also, as recalled by an attendee, Willam Elson, shared reports from the paper at reform meetings.10

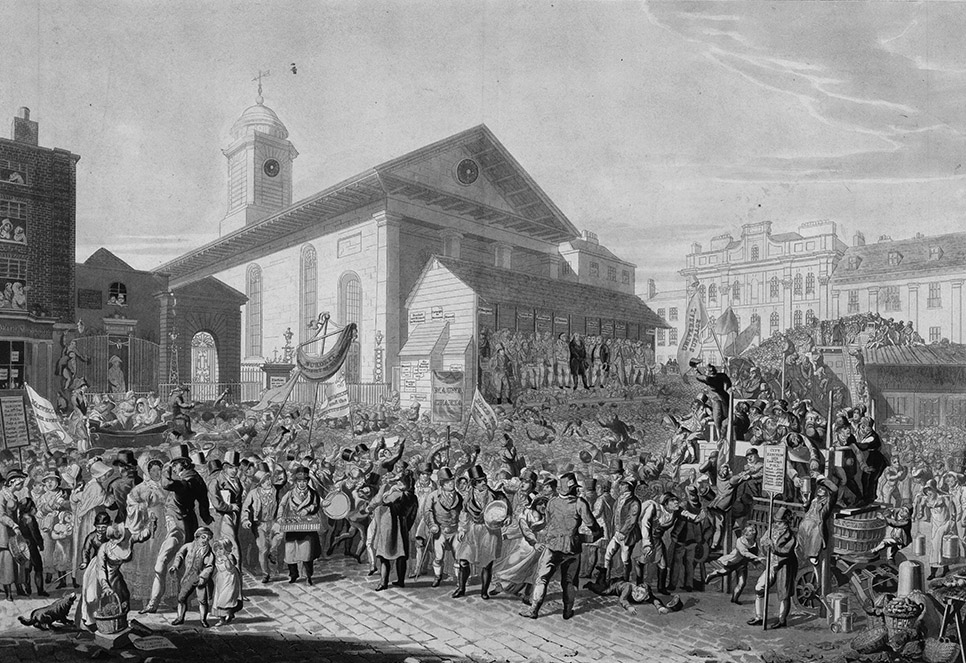

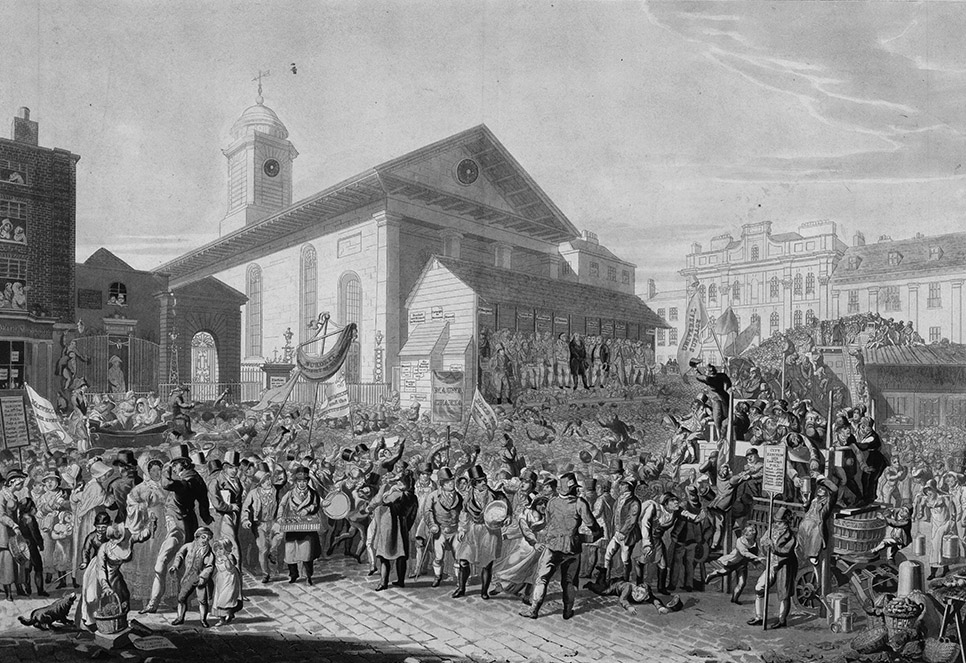

Representation of the election of Members of Parliament for Westminster, by Robert Havell II after George Scharf, 1818.

(Bridgeman Images)

A significant shift in the dynamics of the Home Office had begun with the appointment of Henry Hobhouse as Permanent Under Secretary in 1817, replacing John Beckett. Educated at Eton College and then Oxford University, and a former barrister at Middle Temple, Hobhouse had been Treasury Solicitor since 1812, through the period of the Luddite Revolt.11 He filled the void as Lord Sidmouth gradually retired from day-to-day involvement in the department’s activities, a change brought on by the death of his brother, Hiley, in June 1818, as well as Sidmouth’s own declining health.12 It was Hobhouse who kept up regular correspondence with the magistrates of Lancashire, Cheshire and beyond, passing on to them the opinion of Lord Sidmouth on all proceedings. As a lawyer, he gave measured instructions or, more accurately, advice. He left much of the decision-making to the judgement of local magistrates – albeit based on principles established by the Home Office – thereby ensuring his department would not be directly culpable for any mistakes they made.

The general election of 1818 publicly highlighted the splits that had formed within the reform movement, which had been evident from the Hampden Club convention the previous year. The election ran from 17 June to 18 July. Only 120 of the nation’s 380 seats were contested, one of these being Westminster, lately represented by Sir Francis Burdett and Lord Cochrane. Henry Hunt, with the encouragement of William Cobbett (from his refuge in America), now decided to stand for election there, as he considered that Burdett had effectively abandoned the cause of radical reform, while Cochrane had made it known he would not be standing again. In the initial stages, Major Cartwright was also in the running. Richard Carlile and William Sherwin supported Hunt, with Carlile providing Hunt’s colours, ‘a scarlet flag, with UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE as a motto, surmounted by a Cap of liberty, surrounded with the inscription of Hunt and Liberty’.13 This eye-catching standard was proudly displayed on the hustings at Covent Garden – here a substantial wooden structure, with a raised gallery, located in front of St Paul’s Church in the main square or piazza.

Over the period of the Westminster election campaign, Hunt was attacked in the press and, when on the hustings, by partisan individuals in the crowd. The secretary of the London Hampden Club, Thomas Cleary (now Major Cartwright’s election agent), the same man who had rejected Hunt’s plea for the club to assist Jeremiah Brandreth and his companions – attempted to ruin his candidacy by dirty tricks including crude references to Hunt’s companion, Mrs Vince, and even challenged him to a duel. Eventually, after an ill-tempered contest which was divisive for the reform movement, Burdett and Sir Samuel Romilly were elected (the latter a Whig supporter of parliamentary reform). Burdett, however, came second to Romilly (5,238 and 5,339 votes respectively), with Hunt receiving only eighty-four votes.14 Hunt had been the popular choice among the crowds who gathered to hear his rousing speeches delivered from the hustings, but not among the local householders, who, unfortunately for him, made up the limited electorate.*

Hunt, however, was unbowed: he clearly felt the event deserved celebration and remembrance. He would later recall, with justifiable pride, that:

at the general election in June 1818, for the first time in England, a gentleman offered himself as a candidate, upon the avowed principles of ‘Annual Parliaments, Universal Suffrage, and Vote by Ballot;’ that at this election, which lasted fifteen days, the Cap of Liberty, surmounting the colours with that motto, was hoisted and carried through the streets morning and evening, preceding my carriage to and from the hustings in the city of Westminster; and that these were the only colours that were suffered by the people to remain upon the hustings.

If anyone attempted to remove the banner, the cry would rise up: ‘Protect Hunt’s flag, my lads; touch it if you dare!’15 For his pains, the election organizers sent Hunt an exorbitant bill for £250, representing a third of the construction costs for the hustings.16 He had commenced the journey to reform as a man of means, but his dedication to the cause was chipping away relentlessly at his resources.

Meanwhile John Bagguley, after his release from prison, was teaching at a working men’s school in Stockport. Far from being chastened by his experiences, he had returned to prominence as a radical speaker, along with Samuel Drummond and John Johnston. The slump in trade throughout 1818 had further reduced workers’ weekly wages, not just in the textile industry but in the coal mines and elsewhere. Strikes were now escalating throughout the region.17 Capturing the general mood, Bagguley and his friends were reported to be using ever more violent language during political meetings. ‘Liberty or Death!’ was their refrain, which they encouraged the crowds to chant.

William Boulter described being present at a meeting of three to four thousand people at Sandy Brow on 1 September 1818, at which Bagguley, Drummond and Johnston spoke, alongside the Reverend Joseph Harrison of Stockport, a well-known radical and now something of a mentor to the three men. Bagguley apparently rebuked the assembled crowd for their apathy, asking whether the ‘immortal’ Thomas Paine would have acted with such ‘cool indifference’. He declaimed, ‘If you want a leader, I will lead you, and sword in hand I’ll lose the last drop of my blood in the glorious cause of freedom.’ He also declared that this would be the last occasion for discussion, for ‘they had talked long enough, they must now act: the next time they met would be in the glorious struggle of death or liberty.’18 According to John Livesey, still busy on behalf of the authorities, Bagguley also encouraged the workers to continue their months-long strike action, ‘for it is your Labour that supports everything’.19 John Johnston then arrived and was pulled up onto the hustings. He declared, so said the informants, ‘Oh that I had a sword in my hand to cut off the heads of all tyrants!’ Of Lords Sidmouth and Castlereagh he said: ‘I am regardless of consequences, and say coolly and fearlessly, I will shoot them whenever I can, I would sooner do it than have a dinner and bottle of wine; I say again, I will blow out their brains whenever I have an opportunity; and if I do not live to do it, I hope some of these women will have the opportunity of tearing them limb from limb.’ He hoped that every mother present would put a poker, a knife or a pistol in her son’s hand ‘and send him forth to meet the death of Hampden,† in the cause of liberty’.20 Livesey reported that Samuel Drummond called on the people to arm themselves to regain their ancient rights and their lost liberty, and promised them: ‘For my part, I will stick to you till the last drop of my Blood is expended.’ Finally, ‘as loud as his lungs wou’d admit’, he urged them to ‘get all Armed – for nothing but sword in hand will do at all – Oh! Liberty thou sweet liberty is what I will gain or die in the attempt. Liberty or death!’ He sat down to great cheers.21

The following day, 2 September, Bagguley, Johnston and Drummond gathered their supporters together and marched to Manchester, where they joined thousands of fellow strikers. Despite the anxiety this provoked in the local magistrates, James Norris most notably, the event passed off quietly enough. But Bagguley, Johnston and Drummond were now marked men, with fresh warrants issued against them.22 They ‘got out of the way’ of the pursuing constables, at which John Lloyd, secretary of the Stockport magistrates, who was co-ordinating the response from the authorities, declared sarcastically in a letter to Henry Hobhouse that ‘I hope they are not to be overtaken & that the “true land of Liberty – America!” may be their destination’.23 The three men did not make it as far as the promised land across the sea. They were accosted at Liverpool docks by Joseph Nadin, clapped in irons and taken to Chester Castle on charges of sedition. Writing to the Reverend Joseph Harrison from his cell at the end of September, Bagguley said he believed that revenge was the motive behind his arrest. He quoted Nadin as saying he had now twice had the honour of seeing Bagguley escorted to prison. There followed a tirade against ‘the celebrated Nadin’, ‘this wretch – a stranger to Religion, a savage to Humanity, a Child in virtue, a boy in Honour, a Cipher in Love, but a man in cunning, a Giant in Hypocrisy a monster in Collective vice and a Devil in human form’. Bagguley described how Nadin’s eyes rolled in his ‘Bullhead’ as he enjoyed the moment of putting his prisoner in irons. ‘Oh for another Shakespear [sic] to draw in nature this uncommon savage “Oran Outang”.’ He concludes by asking Harrison how bail might be arranged.24 In fact bail was set so high that there was no hope of releasing them before trial.

The immediate result of the imprisonment of the three reform activists was a cessation of strikes and demonstrations and the reopening of the factories, mills and coal mines. John Lloyd was congratulated for dealing with the situation in a timely and rigorous manner: something the Home Secretary hoped to see demonstrated elsewhere in the region, should the situation arise.25

* Westminster had 12,000 voters from a population of 158,210.

† John Hampden had died in battle in 1643 commanding cavalry in the Parliamentarian army.