‘Witches in politics’

At the dinner following the Manchester Patriotic Union Society’s mass meeting in January 1819, one of the toasts had been, somewhat curiously, ‘to the beautiful Lancashire Witches’. The infamous Lancashire witch trials of 1612 had left an indelible mark on county folklore and belief. Eight women and two men from the area around Pendle Hill, near the East Lancashire towns of Burnley, Padiham and Clitheroe, had been arrested, interrogated – including under torture – and tried at Lancaster Castle for the murder by witchcraft of ten people. One of the accused, Elizabeth Southernes, ‘Old Demdike’, aged eighty, died in her cell. The others were hanged at various locations around Lancaster. It was a story that continued to inspire and appal local antiquarians and authors in the early nineteenth century, including James Crossley and William Harrison Ainsworth, the latter nicknamed the English Walter Scott.*

A hundred years after these terrible events, the term ‘Lancashire Witches’ began to take on a different meaning. As Daniel Defoe recounted, during his tour through Great Britain:

Lancashire Witches are pleasantly said, and not undeservedly, to allude to the Beauty of the Women in this County; but in the times of Superstition, and even since the Reformation, it had a more serious Relation to the general Belief, that there were such unhappy Creatures, who sold themselves to the Devil, to be enabled to do Mischief for a Time: a Belief that obtained much in this particular County, and for which many a poor old Creature suffered.1

Soon afterwards, James Ray, a British army volunteer from Whitehaven during the troubled years of 1745 and 1746, recalled that Lancashire was rife with Jacobite sympathisers. Like Defoe, he commented on the recent use of the term ‘Lancashire Witches’ to denote beauty, but he warned that this could be employed by those of the Jacobite persuasion to seduce unsuspecting loyalists:

In this County the Women are generally very handsome, by which they have acquired the Name of Lancashire Witches… but some of the pretty Jacobite Witches, chuse to distinguish themselves by wearing Plaid Breast-knots, Ribbons, and Garters tied above the Knee, which may be remonstranced as dangerous to the Constitution; for that above a Lady’s Knee is of so attracting a Quality, it’s not only in Danger of drawing his Majesty’s good Subjects in the Civil, but Military Gentlemen off their Duty.2

John Harland’s volume Ballads and Songs of Lancashire: Chiefly Older than the 19th Century includes a sprightly song, from a street-ballad sheet entitled ‘Lancashire Witches’, with the lines:

My charmer’s the village delight,

And the pride of the Lancashire witches,

Then hurrah for the Lancashire witches,

Whose smile every bosom enriches.

Only view the dear heavenly belles,

You’re soon seized with love’s twitches,

Which none could create but the spells,

From the eyes of the Lancashire witches.3

In his edition of Thomas Pott’s 1613 book Discovery of Witches in the County of Lancaster, James Crossley concluded his introduction with the observation: ‘In process of time even the term witchfinder may lose the stains which have adhered to it… and may be adopted by general usage, as a sort of companion phrase, to signify the fortunate individual, who, by an union with a Lancashire witch, has just asserted his indefeasible title to be considered as the happiest of men.’4

A different kind of public attention was drawn to women in the first half of 1819, by a new and, to some, unwelcome development. Women from labouring backgrounds as well as the middling sort were not only supporting the reform movement, but establishing their own Reform Societies.5 The prevailing opinion of the time derided the notion of women entering the public arena. Yet radical ideas and principles were bringing them into the political sphere alongside wage-earning menfolk. Women were the hub of any household: it was they who gave birth to and nurtured the young, and were their offspring’s first teachers. John Saxton had called upon the men at the January 1819 meeting to teach their wives ‘the inestimable blessings of liberty’ and therefore to transfer the principle, metaphorically at the mother’s breast, to the next generation. The involvement of women increased the scale and impact of the reform movement and the mass-meeting forum in particular. By mid-1819, the profusion of these meetings across the country, supported and attended by women, was causing great alarm among the authorities.

As we have seen, after the reinstatement of the Habeas Corpus Act in early 1818, political meetings were organized once more across the northwest. Samuel Bamford recalled one such gathering, at Lydgate in Saddleworth, at which the speakers included John Bagguley and Samuel Drummond. During his own address, Bamford ‘insisted on the right, and the propriety also, of females who were present at such assemblages, voting by show of hand, for, or against the resolutions. This was a new idea; and the women, who attended numerously on that bleak ridge, were mightily pleased with it, – and the men being nothing dissentient, – when the resolution was put, the women held up their hands, amid much laughter.’ The atmosphere may have been light-hearted, but, as Bamford concludes, it was a momentous occasion, for ‘from that time, females voted with the men at the radical meetings… it became the practice’. Further still, ‘female political unions were formed, with their chair-women, committees, and other officials; and from us, the practice was soon borrowed, very judiciously no doubt, and applied in a greater or less degree, to the promotion of religions and charitable institutions’.6

This galvanizing of women’s participation is credited as being the earliest example of organized female activity in British politics. It was, in its early days, very much a northern English – indeed, largely a Lancastrian – phenomenon.7 Female Reform Societies were established in Lancashire and some in adjoining Yorkshire, for example in Stockport, Blackburn, Leigh, Rochdale, Royton, Leeds and Manchester.8 The first to form was Blackburn on 18 June 1819, under the leadership of Alice Kitchen. So novel was this concept that it became national news. Following an announcement in the Manchester Mercury under the subtitle of ‘PUBLIC MEETINGS’, on 1 July 1819 the London Morning Chronicle reported the arrival of the ‘BLACKBURN FEMALE REFORM SOCIETY’:

At Blackburn, near Manchester, a Society has been formed under the above title, from which a circular has been issued to other districts, inviting the wives and daughters of the workmen in the different branches of manufacture to form themselves into similar Societies. They are not only to co-operate with the different classes of workmen in seeking redress of their grievances, but ‘to instil into the minds of their children a deep rooted hatred of the Government and Houses of Parliament,’ whom they are pleased to call ‘our tyrannical rulers.’9

This announcement was repeated by the Leeds Intelligencer with the observation that the aims of this and ‘similar societies’ were ‘most wicked and vicious’.10

On 5 July 1819, members of the Blackburn Female Reform Society paraded to a meeting in their town, chaired by John Knight. According to the report in Black Dwarf, more than thirty thousand people were in attendance. In a satirical letter from ‘The Black Dwarf’ to ‘the Yellow Bonne at Japan’, the former declares: ‘Here the ladies are determined at last to speak for themselves; and they address their brother reformers in a very manly language.’11 How, he ponders, will the law respond? ‘They will not sure be so ungallant, as to call the ladies seditious, or threaten them with imprisonment, and whips!’12 Should, for example, the Attorney General attempt to arrest them for treason, the Black Dwarf believed, ‘he would probably find a jury more disposed to favour the petticoat than the gown. And for the soldiers and police officers, they cannot be arrayed against WOMEN!! That would be despicable in the extreme.’13

In his address, John Knight spoke of the necessity of a radical reform of the House of Commons, calling upon William Fitton to read out the particulars of his proposal. At this point, according to Black Dwarf, ‘a most interesting and enchanting scene here ensued’. The committee of the Blackburn Female Reform Society, with Mrs Kitchen at its head, were desirous of approaching the hustings. The women ‘were very neatly dressed for the occasion, and each wore a green favour† in her bonnet or cap’.14 They were invited to approach and, having ascended the hustings, Mrs Kitchen presented John Knight with a Cap of Liberty, ‘made of scarlet silk or satin, lined with green, with a serpentine gold lace, terminating with a rich gold tassel’. She then asked the chairman to accept and read out an address that ‘embraces a faint description of our woes, and may apologise for our interference in the politics of our country’. This was greeted by ‘very great applause’.15

Such attention to presentation and detail is not insignificant. The pride with which the elaborate Cap of Liberty was fashioned and publicly displayed was wholly appropriate to an area built largely on the textile industry, in which many of the women were directly employed, or to which they were connected through their menfolk and children. In addition, in wearing ‘favours’ and presenting tokens to their male ‘champions’, the women appeared to be evoking ancient chivalric customs with military associations (whether the joust or the battlefield) as well as echoing courtly love and gallantry. There was a decorum and ancient ritual in this gesture, and perhaps a conscious reference to Edmund Burke’s famous declaration of 1790 that ‘the age of chivalry is gone’, made in reaction to reports of the Women’s March on Versailles in early October 1789 and the mob’s ensuing rough behaviour towards the imprisoned king and Queen Marie Antoinette:

little did I dream that I should have lived to see such disasters fallen upon her in a nation of gallant men, in a nation of men of honour and of cavaliers. I thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult. – But the age of chivalry is gone. – That of sophisters, œconomists, and calculators, has succeeded; and the glory of Europe is extinguished forever.16

It has been argued that Burke was celebrating the civility and ceremony of public life as the crucial bond that holds a complex society together: a bond he considered had been undone by the turmoil of 1789, while predicting its full destruction during the Reign of Terror that followed. The attack on the French queen represented the Revolution’s revolt against humanity.17 Mrs Kitchen’s apology ‘for our interference in the politics of our country’ underlines the unexpected nature of the women’s intervention, and thereby reveals how desperate the times had become. The overt gallantry of the leading reformers, in inviting women to join the male speakers – in contrast to the way that they were derided, belittled and denigrated by the opponents of reform – declared that chivalry, or respectful decorum, was far from dead. Rather, it was alive and well in the parliamentary reform movement.

This projection of seemingly conflicting signals for the benefit of the opposition – the embrace of traditional courtesies by radical women agitating for reform – was conscious and highly effective. The presence of women at the Blackburn Reform Meeting wrong-footed the authorities, while their mobilization brought a new energy to the reform movement, after a period of disappointment and setback.18

Having made her appeal, Alice Kitchen handed the women’s address to John Knight, who duly read it out to the assembled throng. The address was full of passion, dignity and power. The women argued that ‘we can speak with unassuming confidence, that our houses which once bore ample testimony of our industry and cleanliness, and were fit for the reception of a prince, are now alas! robbed of all their ornaments’, while their beds, ‘that once afforded us cleanliness, health and sweet repose, are now torn away from us by the relentless hand of the unfeeling tax gatherer, to satisfy the greatest monsters of cruelty, the borough-mongering tyrants, who are reposing on beds of down’ while they had nothing but ‘a sheaf of straw’. And the address drew attention to the suffering of the women’s families: ‘behold our innocent wretched children! … how appalling are their cries for bread!’ Like an invitation from the Spirit of Christmas Present, the women were offering a challenge to their political masters: ‘Come then to our dwellings, ye inhabitants of the den of corruption, behold our misery, and see our rags! We cannot describe our wretchedness, for language cannot paint the feelings of a mother, when she beholds her naked children, and hears their inoffensive cries of hunger and approaching death.’

The address warned that ‘we are not without proof in history of women who have led armies to the field, and carried conquest before them’, and that were it not for the hope of reform, ‘we should long ere this have sallied forth to demand our rights, and in the acquirement of those rights to have obtained that food and raiment for our children, which God and nature have ordained for every living creature, but which our oppressors and tyrannical rulers have withheld from us.’ It ended on a grim note: ‘We look forward with horror to an approaching winter, when the necessity of food, clothing, and every requisite will increase double-fold.’19

In its content, language and tone, the address set the standard for female participation in the reform movement. The women’s testimonies sprang from their own personal experiences, which were amplified with biblical, classical and historical references. They emphasized their traditional roles as mothers, wives and sisters, and dwelt on their arena of expertise, the home. They also hinted at historical precedents for women to play other roles – notably female warriors, evoking the mythical Amazon tribe, the Iceni queen Boudicca and Joan of Arc – which they were choosing, for now, not to emulate. Only Parliament, or more precisely the House of Commons, they insisted, could relieve their individual and collective suffering. But to do so, the House of Commons must truly represent the ‘Common Man’. At this time there is no obvious suggestion that female suffrage was on the agenda, but if all adult males could vote, at least the family as a unit would also be represented.

Samuel Bamford had emphasized the family unit as integral to the struggle for reform in his ‘Lancashire Hymn’, composed to be sung, he hoped, to inspire the hearts and souls of his brother and sister reformers at their political meetings:

Have we not heard the infant’s cry,

And mark’d the mother’s tear?

That look, which told us mournfully

That woe and want were there?

And shall they ever weep again,

And shall their pleadings be in vain?20

The content of the Blackburn Female Reform Society address is not dissimilar to Bamford’s emotive and evocative vision of want and poverty. Here, of course, women were politely and with due decorum (unlike their French sisters) demanding for themselves the changes they desperately needed in their circumstances and that of their menfolk and offspring.

Although female suffrage was not publicly discussed, the activities of the new Female Reform Societies seem to have drawn attention to the plight of women more broadly: their limited education and opportunities for employment, self-expression and personal fulfilment. John Bagguley, for example, actively encouraged the embryonic Female Reform Society in his adopted town of Stockport. He and his fellow agitators for reform Drummond and Johnston had finally come to trial on 15 April, seven months after their arrest. They had been found guilty of conspiracy and unlawful assembly and sentenced to two years’ incarceration.21

On 19 June 1819, from his prison cell in Chester Castle, Bagguley wrote: ‘It appears to me that the female part of the nation have too long been kept in a kind of slavish inferiority[,] their tyranic [sic] lords say that they are slow in their movements… [and to] convert women into Philosophers they say [would] destroy their natural softness nay it would completely metemorphos [sic] these Enchanting[,] these lovely Daughters of [Venus].’

Bagguley argues that, in truth, women ‘can be rational companions to their Husbands’:

they can heighten their joys and alleviate their sorrows, By the strength of understanding they may give good council, by their tenderness sooth the heart in the day of trouble and in the hour of anguish can smooth the bed of sickness and alleviate even the forebodings of despair[,] and to crown all a woman can educate her… Children and train them up to virtue, and Honour and Liberty.

He refers to recent leading English intellectuals, including the classicist and translator Elizabeth Carter (1717–1806), the reformer and writer Elizabeth Montagu (1718–1800) and Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–97), the latter reviled and revered in equal measure for her seminal tract A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) where she argues for a rational education for womankind.22 His comments on women being ‘rational companions’ and educators of children suggest that Bagguley had read, absorbed and been motivated by Wollstonecraft’s powerful arguments.

Bagguley goes on to ask whether a woman’s soul is ‘formed of different materials or derived from a different source than mans [sic]’. In answer, ‘I say no… away then with this vain disparity, and let us see female Newtons, and female Locks, and female Hampdens.’‡ He continues, ‘I begin to think that the inequality of sexes aught to subside; yes ladies exercise your intelects [sic] you have the power, you only want the will to become great[,] do but exercise your wills and you must soon rise.’23

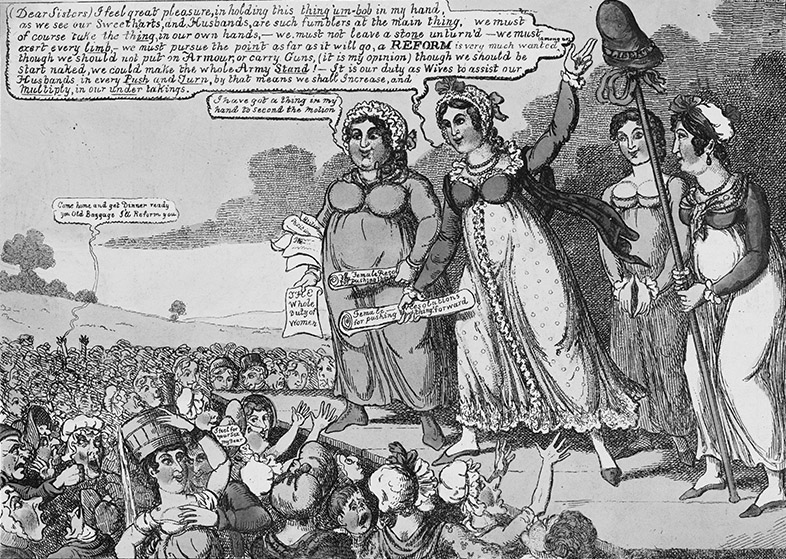

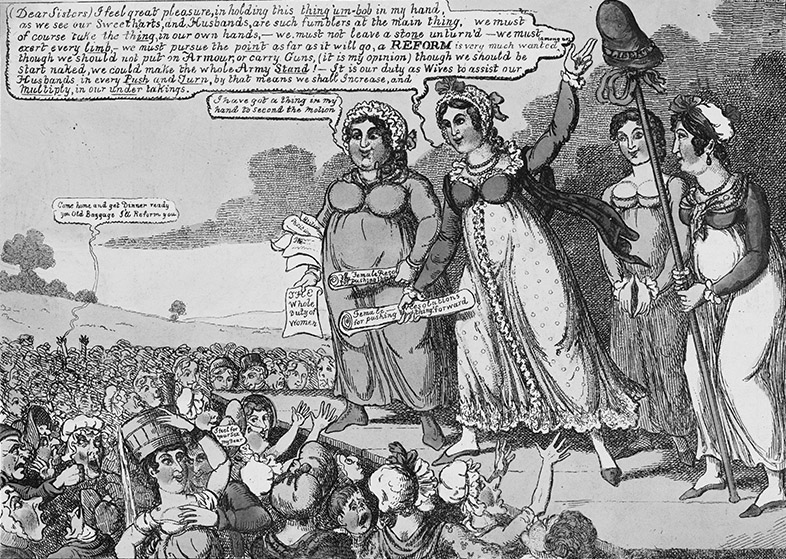

The degree to which female political activity was regarded as a threat to the natural order is reflected in the extraordinary odium directed towards women who engaged in it, both in newspapers and via satires and caricatures. On 14 July 1819, The Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser published a full transcription of the Blackburn Female Reform Society’s address, alongside a letter announcing that a London society was to be established on similar lines. How many Blackburn Female Reformers there were, the author did not know, but ‘there cannot be a doubt that London will out-number all Lancashire in Female Reformers, were we only to form our estimate from the display of female reformation which decorates our streets every night’. He alludes to the capital’s ‘society ladies’, or prostitutes, and to the areas notorious for streetwalkers and brothels, Drury Lane and Covent Garden, where they ‘pour out [in] their hundreds and their thousands, all as well qualified to judge of Universal Suffrage as the Ladies of Blackburn’. Having equated female reformers with London’s whores, the writer next compares them with the coarse-mouthed fishwives at Billingsgate market, which is not only ‘remarkable for excellence of fish’ but also for ‘plainness of speech’. Local magistrates, he goes on, had tried to frighten the ‘Blackburn Petticoat Reformers’ by ordering out the fire engines; ‘I remember that this trick was once played in France, at the beginning of its Revolution, which our Reformers are so desirous of imitating.’ But for ‘Our Female Reformers’, the author says, the engines should be filled with gin, since ‘I am not sure that the stoutest of our Female Reformers may not sink under it; but water has no terrors for them. It is seldom allowed to injure their charms.’ These ‘London Sans-culottes’ and ‘the Poissardes of Lancashire’ are only fit for houses of correction or workhouses, ‘but let us not for a moment think of calling in the military to quell rioters of a description so despicable’, and who, in every sense of the word, are ‘not worthy of powder and shot’. He concludes:

Much wanted Reform among females!!! by J. Lewis Marks, 1819.

(© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Among those female Viragoes there are probably few of the reclaimable kind. A woman must have pretty well unsexed herself before she could join the gangs of Blackburn Rioters. But if there be among the males any well-meaning, however deluded, characters, let those who are better instructed warn them against the danger of associating with, or listening to, those pests of society who would be the first to save their own lives at the expence of theirs. Your’s, &c. R.S.24

No doubt taking inspiration from such diatribes, in August 1819 the printmaker J. Lewis Marks produced a caricature – of the least subtle variety – entitled ‘Much wanted REFORM AMONG FEMALES!!!’ It depicts an open-air public meeting with an all-female group on the hustings. The breasts of all the women are exaggerated, their eyes wide and staring and their faces flushed. The Cap of Liberty perched on a tall staff forms an enormous phallic symbol, held strategically between the legs by one woman; another holds her hands in the shape of a vulva, while others grasp rolled addresses in imitation of erections. In the crowd a young man fondles a milkmaid’s breast, declaring, ‘I feel for your Sex my Dear.’ The main female figure points to the prominent red Cap of Liberty and declaims, ‘(Dear Sisters) I feel great pleasure, in holding this thing “um-bob” in my hand, as we see our Sweethearts, and Husbands, are such fumblers at the main thing, we must of course take the thing, in our own hands.’25

This cruel parody – ripe with sexual innuendo, gender-swapping, and the idea that women only take command when their menfolk are inadequate, sexually as well as politically – appears to satirize the speech given by Susannah Saxton, wife of John Thacker Saxton and secretary of the Manchester Female Reform Society (MFRS), delivered at the society’s inaugural meeting at the Union Rooms on George Leigh Street, Manchester on 20 July 1819 and published in the Manchester Observer eleven days later.26 Saxton began with the phrase ‘Dear Sisters of the Earth’. She declared that soon, under the current system, ‘no thing [sic] will be found in our unhappy country but luxury, idleness, dissipation, and tyranny, on the one hand; and abject poverty, slavery, wretchedness, misery and death, on the other.’ She called upon her audience to ‘unite with us as speedily as possible; and to exert your influence with your fathers, your husbands, your sons, your relatives and your friends, to join the Male Union for constitutionally demanding a Reform in their own House, viz. The Commons House of Parliament; for we are now thoroughly convinced, that for want of such timely Reform, the useful class of society has been reduced to its present degraded state.’ Saxton turned to the late war, which she considered ‘unjust’ and ‘against the liberties of France’, terminating at Waterloo ‘where the blood of our fellow-creatures flowed’ not for the betterment of mankind, but simply to return the Bourbon kings to the throne of France. ‘Our enemies’, she believed,

are resolved upon destroying the last vestige of the natural Rights of Man, and we are determined to establish it; for as well might they attempt to arrest the sun in the region of space, or stop the diurnal motion of the earth, as to impede the rapid progress of the enlightened friends to Liberty and Truth. The beam of angelic light that hath gone forth through the globe hath at length reached unto man, and we are proud to say that the Female Reformers of Manchester have also caught its benign and heavenly influence; it is not possible therefore for us to submit to bear the ponderous weight of our chains any longer, but to use our endeavour to tear them asunder, and dash them in the face of our remorseless oppressors.

‘We can no longer bear’, she cried, ‘to see numbers of our parents immured in workhouses’, where fathers and mothers were separated,

in direct contradiction to the laws of God and the laws of man; our sons degraded below human nature, our husbands and little ones clothed in rags, and pining on the face of the earth! – Dear Sisters, how could you bear to see the infant at the breast, drawing from you the remnant of your last blood, instead of the nourishment which nature requires; the only subsistence for yourselves being a draught of cold water?

‘Remember,’ she continued, ‘that all good men were reformers in every age of the world.’ Susannah named Noah, the Prophets and Apostles as reformers, and then ‘the great Founder of Christianity, he was the greatest reformer of all’. If Jesus returned now and preached against the current Church and State, ‘his life would assuredly be sacrificed by the relentless hand of the Borough-Judases; for corruption, tyranny, and injustice, have reached their summit; and the bitter cup of oppression is now full to the brim.’27

The transcript of this compelling speech, rich with biblical allusions, even enlisting Jesus Christ to her cause alongside more recent political theorists – notably Thomas Paine – was followed by a notice that the MFRS committee would sit every Tuesday evening from six until nine o’clock for the purpose of enrolling new members ‘and transacting other Business relative to the Establishment’.28

In preparation for the mass meeting to be held in August, the MFRS committee designed a banner. This was a large rectangular piece of white fabric, on which was depicted a well-dressed woman in a gown of duck-egg blue, holding the scales of justice and trampling the serpent of corruption. By now other Female Societies, like those of Royton and Stockport, were also preparing their banners or ‘colours’ for the occasion. Royton’s text was ‘Let Us Die Like Men and Not Be Sold Like Slaves’, while Stockport focused on key tenets of the reform movement, ‘Annual Parliament’, ‘Universal Suffrage’ and ‘Vote By Ballot’.

The MFRS, meanwhile, were aiming to process in front of Henry Hunt’s carriage dressed in white, like Vestals honouring a conquering hero of antiquity. In addition to Susannah Saxton as secretary, the society included the president, Mary Fildes (born Mary Pritchard in Cork, Ireland, 1789; she married William Fildes in Cheshire in 1808), Elizabeth Gaunt and Sarah Hargreaves. Inspired by the Blackburn meeting of 5 July, Mrs Fildes intended to present Hunt with the society’s banner and then hand him an address to read out to the vast assembly, in the full expectation of gallantries, respect and cheers as reported by Black Dwarf from that earlier meeting. This address would be one of the set pieces of the occasion. It read:

Sir – Permit the Female Reformers of Manchester, in presenting you with this flag, to state, that they are actuated by no motives of petty vanity. As wives, mothers, daughters, in their social, domestic, moral capacities, they come forward in support of the sacred cause of liberty – a cause in which their husbands, their fathers, and their sons, have embarked the last hope of suffering humanity. Neither ashamed nor afraid of thus aiding you in the glorious struggle for recovering your lost privilege – privileges upon which so much of their own happiness depends; they trust that this tribute to freedom will animate you to a steady per[s]everance in obtaining the object of our common solicitude – a radical reform of the Commons House of Parliament. In discharging what they felt an imperative duty, they hope that they have not ‘overstepped the modesty of nature,’ and they shall now retire to the bosoms of their families with the cheering and consolatory reflection, that your efforts are on the eve of being crowned with complete success.29

The address concluded, ‘May our flag never be unfurled but in the cause of peace and reform! and then may a female’s curse pursue the coward who deserts the standard!’30

The use of the term ‘curse’ may be a sly reference to the Lancashire Witches, while her threat of pursuing anyone who ‘deserts the standard’ echoed Henry Hunt’s dramatic declaration at St Peter’s Field the previous January. Fildes had clearly taken note. Her admiration for Hunt is shown by the name of one of her sons, Henry Hunt Fildes (born 1819). The names of her other boys, Thomas Paine Fildes (1818) and John Cartwright Fildes (1821), stand as further testament to her radical politics.

Three weeks after Mary Fildes and her companions had gathered at the Union Rooms, another mass political meeting was held in the market place at Leigh. One of those present, Mr. Wright, later recounted:

As soon as Mr. Bamber [a Quaker] was chosen for their Chairman, a parade of the Female Reformers took place, headed by a Committee of 12 young women. The Members of the Female Committee were honoured with places on the carts [hustings]. They were dressed in white with black sashes, and what was most novel, these women planted a standard with an inscription “No Corn Laws, Annual Parliaments, and Universal Suffrage”; as well as another standard, surmounted with the cap of Liberty on the platform. Both the flag and the cap were presents from the Ladies Union!! I was seated by the side of these patriotic ladies, and was informed of their rules and regulations, which I am certain no one of common sense in London, would believe it was capable of bringing women into an organised system of operation.

He closed with a familiar comment: ‘These Lancashire women are proverbially witches in politics, (if not in beauty).’31

* Ainsworth penned a celebrated novel, The Lancashire Witches, serialized in 1848 and then published complete in 1849, inspired by James Crossley’s writings.

† The green favour could have been a ribbon, an early French revolutionary symbol, or, more likely, a laurel sprig signifying peace.

‡ English Enlightenment figures: the natural philosopher and mathematician Sir Isaac Newton, the philosopher John Locke and the politician and patron saint of the reform movement, John Hampden.