‘A beautiful morning’

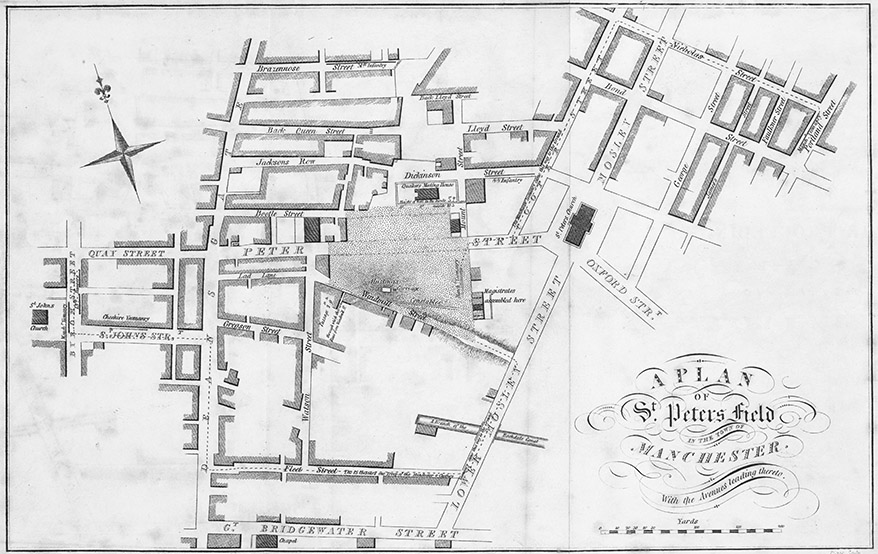

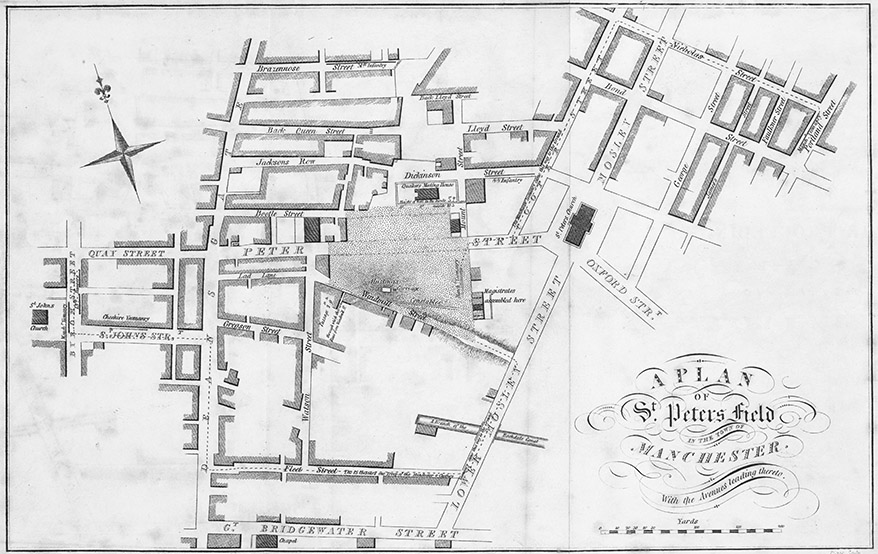

On Monday 16 August, as the sun rose over St Peter’s Field, all was quiet. The Quaker Meeting House, with its high-walled burial ground, lay to the north on Dickinson Street, while the distinctive Grecian exterior of St Peter’s Church could be seen, set a little back from the field itself, to the northeast. The walled garden and terraced houses on Mount Street enclosed the eastern side of the ground and Windmill Street ran at a diagonal along the south. Watson Street formed the short western edge of the field, connecting at its northern point with Peter Street. The latter traversed the field from St Peter’s Church in the east, eventually meeting Deansgate to the west, the town’s main north–south thoroughfare. Beyond the buildings, the skyline was punctuated by factory chimneys, the towering modern obelisks that had amazed the Swiss visitor, Hans Escher five years before. On this morning, however, many of the clattering machines within these factories would fall silent, and then, unusually, no smoke would be seen belching forth into Manchester’s stricken air.

One of the first to arrive at St Peter’s Field was Thomas Worrall, assistant surveyor of Manchester. Prior to the abandoned meeting on 9 August, he and his men had cleared stones, sticks and ‘every thing which could be used in an offensive manner’1 from the field itself and adjoining streets. Returning a week later, by eight o’clock they had removed a further quarter cartload of stones, but now, he later recalled, the field remained clear of such debris.

John Tyas, a reporter from The Times newspaper in London, had arrived in Manchester the week before. While in the town he ‘had heard much conversation about the meeting on 16th’ and on that Monday, he left his lodgings early to see the people gathering on the field and to witness the preparations for Henry Hunt’s arrival. ‘I was on the alert,’ he recollected, as his paper was ‘always giving the most voluminous accounts of things of this kind’.2 When he arrived at eight o’clock, just as Mr Worrall and his men were completing their task, Tyas noted ‘very few people’3 on the field, and even after two and a half hours had passed, there were but ‘250 idle individuals’ gathered.4

Meanwhile William Hulton and nine fellow magistrates from the counties of Lancashire and Cheshire – including the Reverend William Hay, the Reverend Charles Ethelston, Colonel Ralph Fletcher and James Norris – convened at the Star Inn on Deansgate, a hostelry often used by those magistrates such as Hay who lived further afield.5 They breakfasted and then, between ten and eleven o’clock, made their way to Mr Buxton’s house at the lower end of Mount Street. This house overlooked the field, providing an excellent position from which to monitor events. The magistrates established themselves in the front room on the first floor and waited. Between half past eleven and midday, as crowds were beginning to congregate on the field, they received ‘information on oath, relative to the approach of large bodies of people’.6 These expressions of concern from local people, alarmed at what they had heard about the nature of the meeting and the possible behaviour of its participants, would inevitably influence the magistrates’ decision-making. The meeting was not in itself illegal, as William Hulton had confirmed, and they had judged it best, interpreting the advice from the Home Office, to allow it to take place.7 But if seditious language was used, if the crowd was incited to violence and riot, then they could and would act. Hulton, by his own admission, spent most of his time at Mr Buxton’s house writing instructions, in his capacity as chairman of the bench of magistrates for the two counties and therefore of this special meeting, ‘but,’ he later recalled, ‘I frequently looked out of the window, and saw large bodies of men approach.’ He describes them arriving with banners and to the sound of bands, and apparently organized into divisions, with people walking beside them bellowing commands. In his testimony, Hulton repeatedly emphasized the regularity with which the groups marched. To better see what was happening, he had a ‘glass to look through’,8 which could have been a small telescope or spyglass, or, as some historians have interpreted it – given his cultivated manners and dandified appearance – opera glasses.9

During this time, as William Hulton recalled, the hustings from which Henry Hunt would address the crowd – on this occasion constructed from two carts lashed together, with planks on top creating a stage – was placed, at the insistence of the magistrates, so as to allow a double line of constables to reach from the platform to Mr Buxton’s front door.10 Between three and four hundred special constables had volunteered to police the event, many recruited within the previous forty-eight hours. According to one Chief Constable present, Jonathan Andrew, ‘the persons selected were householders, and as respectable as they could get them’,11 with himself, Joseph Nadin and John Moore in overall command. Among these special constables were Richard Holt, a dyer from Manchester, Robert Hughes, a builder and innkeeper, and John Barlow, a merchant.12 Barlow had not intended to go to the meeting ‘in an official capacity’, but while attending to business at the Exchange, he saw men carrying what he believed were large bludgeons and hedge stakes, which ‘created alarm in his mind’ and ‘changed his intention’. He recalls that it was ‘his duty to give every assistance to preserve the public peace: He did so, on account of the alarm which the appearance of the people had created.’13 Some residents had closed and even boarded up their shops in anticipation of trouble breaking out. Jeremiah Smith, headmaster of Manchester Grammar School, considered it prudent, for the safety of his scholars, to close the school for the entire day.14

A Plan of St Peter’s Field by C. Wheeler, 1823.

(The John Rylands Library, Manchester)

The constables formed their lines as directed and Nadin began to patrol up and down the narrow avenue they had created through the crowd.15 According to his account, he was barracked as he passed. Some called out, ‘That’s Joseph… he is great guts, he has more meat in his belly than we have’; others dubbed the constables ‘the black mob’ and declared, ‘They have very good coats on their backs – better coats than we have’, or shouted encouragement to ‘knock him down, and keep him down’.16 Nadin also observed that certain strangers in the crowd were heckled with the term ‘spy’.17 If Nadin’s account is accurate, these expressions show the resentment that Manchester’s poor felt towards those who could wield the full force of severe laws against them. Even Nadin himself later observed, regarding the appearance of those that were shouting at him, ‘I don’t know [if] the people were fed; Some of their coats were very bad.’18

Just after the lines of constables were formed, both Nadin and Hulton (the latter here quoted) noticed that ‘a number of men had rushed in, locked their arms together, and surrounded the hustings’.19 Other witnesses believed that this was done to prevent the hustings from being disturbed but, in Nadin and Hulton’s opinion, the clear aim was to prevent the avenue of constables from reaching the platform. Jonathan Andrew stated that after the constables had formed up, the platform was purposely moved further away from Mr Buxton’s house and the resulting gap immediately filled by a large group of men. Andrew was convinced that the intention was to cut off the lines of communication between the magistrates, the constables and those on the hustings.20 Whatever the reality – the differing recollections hint at both the confusion of the moment and the subsequent desire to lay blame elsewhere – there was a palpable mood of suspicion and mistrust, and tensions were already mounting.

At around this time, the Reverend Edward Stanley, Rector of Alderley in Cheshire, had arrived in Manchester and was riding along Oxford Road and Mosley Street towards Deansgate, where he had an appointment to meet Mr Buxton at about one o’clock. On the way, he passed the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry gathered in Pickford’s yard on Portland Street. A little later, he encountered several parties of people, including the large Ashton contingent arm in arm, some carrying banners, and with bands playing. As the morning progressed some of these banners would be placed around the vacant hustings, alongside a wooden sign on a stick with the words ‘Order! Order!’ painted on it, in preparation for Henry Hunt’s arrival.21 Discovering Mr Buxton was not at his Deansgate shop, Stanley made his way across St Peter’s Field to Buxton’s house, where the magistrates had gathered. He had hoped to avoid the crowds and the mass meeting, but, in the event, he found himself by chance in the thick of the action. Unfamiliar with Manchester, he simply had to wait until the meeting was over and the streets were passable once more. He would also be, again by accident, one of the most important witnesses to the coming events. Stanley was of the same social and professional class as the magistrates, and knew one of them, Thomas William Tatton, very well; he might be expected to have had a natural loyalty and like-mindedness to them. Yet, crucially, he was one of the most disinterested and therefore reliable individuals present.22 And, as he was one of the few people on that day to have a similar view of the field to the magistrates, Stanley’s evidence forms a critical commentary on their recollections of what they saw and heard.

Stanley’s account begins: ‘I saw no symptoms of riot or disturbances before the meeting; the impression on my mind was that the people were sullenly peaceful.’23 He was curious and somewhat excited about the extraordinary spectacle before him. From his first-floor window he could see, to the west, the hustings located midway along Windmill Street. He also observed the men forming a barrier around the hustings, who he assumed were special constables, and the double line of constables extending to the front door of the house, a distance, he calculated, of about one hundred yards. The corridor created by these lines, two or three men deep as Stanley perceived them and about two hundred strong, was established partly, as Jonathan Andrew confirmed, ‘in order that they might hear the Orators, convey it to the Magistrates, and keep up the communication’.24 It would also allow swift access if an arrest were necessary – something that the men obstructing the hustings must have realized.

Behind the hustings, making up the western half of Windmill Street, was a row of dwellings among which stood the Windmill public house, just ten yards from the platform. Along the eastern length of the street was a raised area of rough ground. Here a large group of people, mainly women, had a good view of the field and the approaches to it. At this moment, Edward Stanley describes the ‘mob’ on the field as a ‘vast concourse of people in a close and compact mass’ which ‘surrounded the hustings and constables, pressing upon each other apparently with view to be as near the speakers as possible’.25 From his vantage point, Stanley considered that despite the size of the central crowd people were still able to make their way around the area without too much hindrance. His observations indicate that there was a dense concentration of people immediately around the hustings, thinning towards the outer edges of the field and not too constrained. But this may not have been the experience of those within the crowd itself.

Before midday, John Smith, editor of the Liverpool Mercury, was standing near the hustings watching with great interest the various parties arriving on the field. He had been invited by John Knight and the committee to join them on the day but had declined, as he did not ‘like to take part in the politics of another town, in a public capacity’.26 As an independent reporter, albeit one with deep sympathies for the reform movement, he recalled observing the people and being ‘struck with the orderly manner in which they advanced’.27 He overheard the conversations of those standing around him and declared to them that he presumed they ‘were all friendly to Parliamentary reform. They all said, yes.’ Smith asked, ‘peaceably so, I hope’, to which they responded, ‘Nothing but peace and freedom do we seek.’ Between midday and one o’clock, he noted, the crowd increased considerably. At over six feet in height, Smith had a good view over the heads of those around him. He observed ‘a great many women and children’ among the crowd, as well as ‘many old people’ with walking sticks. He remarked that the crowd in general ‘appeared many of them respectable, and clean dressed, as if they came to a holiday feast’. In contrast to John Barlow’s recollections of public disquiet, Smith stated, ‘I saw no alarm in the respectable persons of the town who had attended the meeting, either expressed in their countenances or conduct’. He took many of them to be ‘inhabitants of Manchester from their dress and conversation’.28

Archibald Prentice spent some time that morning walking around the edge of the field, mingling with the groups who were standing there, chatting and laughing, before he returned to his house in Salford. As he passed by, he asked some women whether they were afraid, to which they replied, ‘What have we to be afraid of?’29

Looking past the central mass and the less densely peopled area just beyond it, Stanley could see yet more crowds standing in a greater concentration around the edges of the field, whom he believed to be spectators, as distinct from participants. Of the participants, he says, the ‘radical banners and caps of liberty were conspicuous in different parts of the concentrated mob, stationed according to the order in which the respective bands to which they belonged had entered the ground, and taken up their positions’.30 The array of brightly coloured banners, fluttering above the hustings and being flourished throughout the crowd, lent the proceedings an almost heraldic dash. All were emblazoned with words of inspiration or challenge; they also had a military or regimental aspect embodied in the term ‘colours’, as Samuel Bamford described those from Middleton. These were civilian legions then, rather than a mob, marching and assembling under the colours of Liberty, Equality and Brotherhood.

Some of the banners, however, with their slogans such as ‘Liberty or Death’ and surmounted by the distinctive red Caps of Liberty – viewed by many as the symbol of violent revolution rather than freedom – were more provocative and disturbing. They were blamed by some observers for raising fears that violence would break out against citizens and property. Already thousands of people had arrived in Manchester from all directions, many of them strangers to the town, over a relatively short space of time – according to John Tyas and John Smith the main body converged on the field within two hours – creating an inevitable tension and unease among some of the town’s residents. A key purpose, after all, of these mass meetings was a powerful display of numerical strength and significant collective will, in order to overawe the authorities. There were those on each side who hoped the other would be the first to move beyond the bounds – transgressing the constitution – and thus forfeit public support.

William Hay considered ‘the assemblage of such a large number of people to be a breach of the peace, according to the rules of common sense and the best law authorities’. As he watched the columns of people carrying ‘dreadful emblems and flags, he could not help considering it dangerous to the public peace; even singly these things denoted a bad purpose, but taken altogether, no man in common sense could think otherwise’.31 In reality, very few of the banners bore inscriptions beyond the basic demands of the reform movement, ‘Universal Suffrage’, ‘No Corn Laws’, ‘Parliaments Annual’ and so on: none of which could have come as a surprise, nor be judged particularly aggressive or threatening. Even the banner declaring ‘Equal Representation or Death’ was not an omen of bloody revolution, as one contemporary reasoned. Rather, interpreted in a patriotic light, it meant that lack of fair representation brought political death; alternatively, it expressed the desire to die rather than be subject to despotism. ‘What Englishman’, this author concludes, ‘but would join in the wish, or the expression!’32

The Middleton and Rochdale party, initially six thousand strong, had been joined by others as they walked through towns, including Blackley, on the journey to Manchester. At Harpurhey some among them were refreshed ‘with a cup of prime ale from Sam Ogden’s tap’.33 On the sound of a bugle, they formed up again and continued on their way. William Elson said there ‘was nothing on the road that induced me to think there would be any disturbance; every thing was peaceable and orderly.’34

As they neared Manchester, their leader, Samuel Bamford, was convinced that they would be stopped on the order of magistrates, that the Riot Act would be read and the party instructed to disperse, but the roads ahead were clear. Bamford ‘began to think that I had over-estimated the forethought of the authorities; and I felt somewhat assured that we should be allowed to enter the town quietly’.35 On the road to Collyhurst, a messenger arrived from Henry Hunt, requesting that the party meet him at Smedley Cottage and lead him into Manchester. Bamford attempted to ignore this, mainly, he later tells us, for practical reasons, but eventually he was persuaded to comply and therefore pander, in his opinion, ‘to the vanity of our “great leader”’ by heading Hunt’s triumphant procession from Smedley Cottage.36

On the outskirts of Manchester, as they moved towards Smedley Cottage, they met a group of poor Irish weavers, with a banner ‘whose colour was their national one, and the emblem of their green island home’.37 The Middleton band struck up ‘Saint Patrick’s day in the morning’ in their honour, and their new companions, as Bamford describes them, whooped and laughed as they danced along. When they eventually arrived in Oldham Street, one of the town’s main arteries, which would take them near their destination, the Middleton and Rochdale party were ‘frequently hailed… by the cheers of the townspeople’. Here they learned that several parties had already passed by and were congregating on the field, including the Lees and Saddleworth Union led by Bamford’s friend Dr Healey, ‘walking before a pitch-black flag, with staring white letters, forming the words, “Equal Representation or death.” – “Love,” – two hands joined, and a heart; all in white paint’. As Bamford observed, Healey’s banner was ‘one of the most sepulchral looking objects that could be contrived’.38 Its dismal appearance and tone were noted by several witnesses, who failed to recall that ‘Love’ also featured.39 At this moment Bamford realized, with secret pleasure, that they had somehow missed and therefore lost Hunt’s procession: ‘I was of opinion that we had rendered homage quite sufficient to the mere vanity of self-exhibition; too much of which I now thought, was apparent.’

Some of the Middleton party had, however, gathered around Smedley Cottage, including Lucy Morville, a widow from the town. She walked along holding hands with her youngest son, aged nine, until they came near to the cottage, where she met up with her elder son, aged twelve. She held his hand too, ‘stopping with both till Mr. Hunt came from the cottage. I then went to St Peter’s-field, a nearer road than the procession, with my two boys.’40

The Waterloo veteran John Lees, now employed in his father’s factory, had left his family home in Oldham between eight and nine o’clock in the morning, wearing suitably unworkmanlike clothing, including a corbeau (dark brown) coat.41 Understandably he had not told his family where he was going. When asked about his son’s state of health that morning, Robert Lees considered him ‘as hearty as ever he was since he was born’. He met fellow townsman Joseph Wrigley on Oldham Green and they began the eight-mile journey south to Manchester as part of the large local contingent, including marchers from Saddleworth and Lees (among whom was Dr Healey), Mossley and Oldham, all under the overall leadership of John Knight. As elsewhere, posters had been put up in Oldham with a message from Henry Hunt desiring ‘the people to go to the meeting peaceably, and without arms’. According to the cotton spinner William Harrison ‘they did so’, and ‘were without sticks or any thing’.42 Joseph Wrigley recalled that John Lees ‘was in good health and spirits’.43 Jonah Andrew, a cotton spinner from Leeds, caught up with them at Hollingswood and walked with John Lees to Deansgate, where, in the throng, they became temporarily separated. He was then with John on St Peter’s Field, about an hour before Henry Hunt’s arrival, while the hustings was being set up. At some point John Lees sat or stood on the planks that made up the platform. Joseph Wrigley, too, recalled sitting on the hustings, with his friend now standing nearby: ‘We were then both close together, with many women and children among us.’ They agreed that they would walk home together later.44 From their collective descriptions the general ambience appears to have been one of calm anticipation, with people mingling and chatting together while patiently awaiting the famous orator’s arrival.

The man of the moment, Henry Hunt, had awoken at Smedley Cottage and, looking out of his bedchamber window, declared it ‘a beautiful morning’. Glancing down into the street, he ‘beheld the people, men, women, and children, accompanied by flags and bands of music, cheerfully passing along towards the place of meeting’.45 He later noted: ‘Their appearance and manner altogether indicated that they were going to perform an important, a sacred duty to themselves and their country, by offering up a joint and sincere prayer to the Legislature to relieve the poor and needy, by rescuing them from the hands of the agents of the rich and powerful, who had oppressed and persecuted them.’46 No doubt that is exactly what many present were thinking. For others, though, it was little more than an unusual and welcome break from the relentless rhythm of their working lives.

Richard Carlile had walked the three miles from the Star Inn, where he was staying, to Smedley Cottage to join Hunt’s parade.47 He recalled that a crowd began to congregate around the house at eleven o’clock, and an hour later the hired barouche, a stately open carriage, arrived.48 Henry Hunt, Joseph Johnson, Richard Carlile and John Knight, who had also now joined them, climbed aboard.49 Hunt noted, in his Memoirs, that the form of the meeting had already been agreed – he was to chair it and a few others would be invited to speak. As they set off they were accompanied by a crowd, buoyed by the festive spirit, which gradually gained in size as the procession weaved its way through central Manchester, all the while a band playing before them. In the distance, Richard Carlile recounted, ‘bodies of men were seen… marching in regular and military order, with music and colours. Different flags were fallen in with on the road, with various mottoes’ such as ‘TAXATION WITHOUT REPRESENTATION IS TYRANNY’ and ‘WE WILL HAVE LIBERTY’, many adorned with Caps of Liberty.50

Soon after leaving Smedley Cottage, Hunt and his companions met Mary Fildes, Susannah Saxton and their large group from the Manchester Female Reform Society, ‘handsomely dressed in white’.51 Mrs Fildes was holding the society’s magnificent emblematic banner, while Mrs Saxton was carrying the address, on a scroll, to be read out on the hustings and then presented to Henry Hunt with due ceremony. This party now followed the barouche two by two, while Mary Fildes, at Hunt’s suggestion, ‘rode by the side of the coachman, bearing her colours in a most gallant stile [sic]’. Hunt noted that ‘though rather small, she was a remarkably good figure, and well dressed’ and ‘it was very justly considered that she added much to the beauty of the scene’.52 Far from simply being a gallant gesture on Henry Hunt’s part, Mary Fildes’s prominence within the party, as he says, set the tone of his procession, although later he felt compelled to justify exposing her to public scrutiny and comment. Among many observers, both men and women, her presence would be deemed wholly inappropriate, even wilfully provocative.

Certainly, such confident possession of what was traditional male territory, a public political meeting, inevitably opened the sisterhood up to abuse. The banner slogan chosen by the Royton Female Reform Society, ‘Let us die like men, and not be sold like slaves’,53 was also no doubt viewed by many onlookers as an unladylike and provocative sentiment. According to The Times reporter John Tyas, who was now watching the procession, members of the Oldham Female Reform Society were mocked in the street by other women: ‘They viewed these Female Reformers for some time with a look in which compassion and disgust were equally blended; and at last burst out into an indignant exclamation – “Go home to your families, and leave sike-like matters as these to your husbands and sons, who better understand them.” The women who thus addressed them were of the lower order in life.’54 Henry Horton of The New Times, another London paper, described Mary Fildes in the 18 August edition as ‘a profligate Amazon’. When Horton was asked why he had characterized her in this way, he answered that it was ‘because I thought her appearance in the manner and place where I saw her, justified the observation’.55 In similar vein, the Manchester Chronicle later declared that some of the women had ‘come to the meeting under such ideal pomp, and with a demeanour the reverse of every thing that man delights to see in woman’.56

In his own and Mary Fildes’s defence, Henry Hunt later argued that ‘as she was a married woman of good character, her appearance in such a situation by no means diminished the respectability of the procession, the whole of which was conducted with the greatest regularity and good order’.57 Richard Carlile recalled that Mrs Fildes, far from being visibly distressed by any verbal attack, ‘continued waving her flag and handkerchief until she reached the hustings’.58 He also emphasizes the presence of women in the crowd ‘from the age of twelve to eighty’ who, rather than abusing the female reformers, were seen energetically cheering ‘with their caps in their hand, and their hair in consequence, dishevelled’. Indeed, ‘the whole scene exceeds the power of description.’59

The barouche took the route from Shudehill to Hanging Ditch and Market Place, then along Deansgate towards St Peter’s Field.60 When it passed the Exchange, ‘where the people were cheering most loudly, and Hunt and Johnson joining in the cheers’,61 John Tyas, still standing among the crowds on Hunt’s processional route, came alongside the barouche. Hunt later described him as ‘a gentleman of a most respectable family and connections’ who had ‘long occupied the station of reporter to the Times Newspaper, a lucrative and responsible situation’.62 Tyas asked if he might join the party on the hustings, and with Hunt’s consent, as the barouche continued on its way through the crowds, he clung gamely to the carriage door.63 From this position, Tyas observed that as the barouche passed the Star Inn on Deansgate, where the magistrates had earlier gathered, the accompanying crowd hissed and hooted, although he also states that Henry Hunt took no part in this, nor did he encourage such behaviour.64 James Moorhouse joined Hunt’s party soon afterwards and, with the barouche crammed with people and to the cheers of the crowds, they proceeded towards St Peter’s Field.

Meanwhile, Samuel Bamford and his party, having passed through Piccadilly and then down Mosley Street, walked along one side of St Peter’s Church and then ‘wheeled quickly and steadily into Peter-street, and soon approached a wide unbuilt space, occupied by an immense multitude, which opened and received us with loud cheers. We walked into that chasm of human beings, and took our station from the hustings across the causeway of Peter-street; and remained, undistinguishable from without, but still forming an almost unbroken line, with our colours in the centre.’65 As Bamford recalled, this was half an hour before the barouche appeared. Mima Bamford had been walking alongside her husband but then lost sight of him: ‘Mrs. Yates, who had hold of my arm, would keep hurrying forward to get a good place, and when the crowd opened for the Middleton procession, Mrs. Yates and myself, and some others of the women, went close to the hustings, quite glad that we had obtained such a situation for seeing and hearing all.’66 Samuel Bamford says, ‘My wife I had not seen for some time; but when last I caught a glimpse of her, she was with some decent married females; and thinking the party quite safe in their own discretion, I felt not much uneasiness on their account, and so had greater liberty in attending to the business of the meeting.’67

The Reverend Edward Stanley was on the first floor of Mr Buxton’s house, awaiting Henry Hunt’s arrival, when ‘a murmur running through the crowd prepared us for his approach’.68 At this point, Stanley left the magistrates – he does not comment on their reaction to either Hunt’s appearance or the scale of the gathering – and, climbing the stairs to the second floor, he positioned himself at the front window. He recalled that he was now ‘commanding a bird’s-eye view of the whole area, in which every movement and every object was distinctly visible’.69 As he watched, he noted that the arrival of Hunt’s carriage was signalled by ‘a tremendous shout’ from the crowd. Directly below, William Hulton heard an ‘extraordinary noise’ which made him get up from his paperwork and walk to the window to look out over the now densely populated field. Like Stanley, Hulton confirmed that from this window ‘I had a view over almost the whole of St. Peter’s area’.70 The noise greeting Hunt was, he said, like nothing he had ever heard before, and he hoped he would never experience such a thing again.71

The barouche, with Mary Fildes still perched prominently on the driver’s seat, slowly made its way across the crowded ground towards the hustings. William Harrison was watching the procession and particularly recalled the figure sitting atop the carriage, whom he describes as the ‘most beautiful woman I ever saw in all my life… all in white, and had on a straw bonnet’.72 Samuel Bamford also noted the single ‘universal shout from probably eighty thousand persons’73 (the numbers are now thought to have been between sixty and eighty thousand) as the carriage entered the field, along with the ‘neatly dressed female’ seated at the front. Such comments confirm how unusual it was to see a woman so prominent within a political gathering, confirming Hunt’s instinct for the well-timed gesture. Bamford goes on to relate that once on the field, Henry Hunt, wearing his distinctive white hat, ‘stood up in the carriage to accept the cheers of the crowd’.74 Compare this triumphant cavalcade, accompanied by the enthusiastic shouts of thousands of working people, to the descriptions of the Prince Regent in his golden coach and among his military escort, with little but the abuse and disdain of his father’s subjects ringing in his ears.

Musicians had been playing throughout the barouche’s journey, mixing popular folk songs, hymns and the like. When the carriage entered the field, according to several witnesses, a band mischievously struck up ‘See the Conquering Hero Comes’ from Handel’s Judas Maccabaeus, an oratorio composed in celebration of the Duke of Cumberland’s crushing of the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion. This militaristic tune, with march-like drumming, was taken up by other musicians and bands across the field. It was followed, according to some witnesses, by spirited renditions of ‘Rule Britannia!’ and then, in more solemn tones, of what was by now considered the British national anthem, ‘God Save Great George Our King’ – again an anthem in support of the Hanoverian dynasty, made popular during the ’45 rising.75 John Smith of the Liverpool Mercury, standing near the hustings, thought he heard the distinctive drum beat of ‘God Save the King’, as he calls it, and saw that those nearest the band had uncovered their heads in respect. Someone nearby confirmed it was the national anthem, at which Smith declared, ‘I am happy to hear it.’76 Despite this being a mass meeting in support of radical parliamentary reform, it is clear that loyalty and respect were still being shown towards the Crown.

Samuel Bamford, meanwhile, judged that at this moment Henry Hunt was surveying the vast crowd with a mixture of pleasure and amazement, with the weight of responsibility playing on his mind. Bamford, standing within this sea of people, felt its power ‘for good or evil’ and considered the sole burden of directing this immense, volatile energy rested on him ‘who had called it forth’: namely Henry Hunt. ‘The task was great, and not without its peril.’77

Unlike Bamford, of course, Hunt had addressed large crowds in London and elsewhere, some calculated at over one hundred thousand strong, and had succeeded, despite intimidation from third parties, in maintaining a peaceable assembly while achieving the impact of a mass demonstration. The January meeting here in Manchester had occurred with no disruption, and Hunt can be forgiven for feeling confident that the same would be true on this day, although the current gathering was of a different order of magnitude altogether. As Hunt himself recalled, the impression was astonishing: ‘When I entered the field or plain, where the people were assembled, I saw such a sight as I had never before beheld. A space containing, as I am informed, nearly five acres of ground, was literally covered with people, a great portion of whom were crammed together as thick as they could stand.’78 He had wanted a crowd unprecedented in its size and he had got it. With one eye to posterity, and with no little hyperbole, Hunt asserts in his Memoirs: ‘Let the reader who was not present picture to his imagination an assemblage of from 180 to 200 thousand English men and women, congregated together to exercise the great constitutional right of laying their complaints and grievances before the throne, and when he has done this, he may form an idea of the scene which met my view.’79 Some, Samuel Bamford for one, would dismiss such grandiloquence as an example of Hunt’s self-serving bluster and vanity. There is undoubtedly bombast – as well as hyperbole – in his pronouncements. But there is also great pride, patriotism and passion, emotion even, in this description. Hunt understood all too well the gravity of the occasion, for all the carnival atmosphere, the responsibility of bringing so many people together, and the great work still to be done to achieve their collective aims. The meeting on St Peter’s Field was one important further, rather than final, step on the glorious road to radical parliamentary reform. He also believed, fervently, that right was on his side and that history would prove it.

Henry Hunt noted the striking up, in his honour, of Handel’s famous tune by ‘ten or twelve bands’ and that ‘eighteen or twenty flags, most of them surmounted by a Cap of Liberty, were unfurled, and from the multitude burst forth such a shout of welcome as never before hailed the ears of an individual, possessed of no other power, no other influence over the minds of people, except that which he had gained by an honest, straight-forward discharge of public duty.’80 The barouche made slow progress through the throng, John Tyas still clinging to the side, accompanied by cheers and roars. As they arrived alongside the hustings Henry Hunt, Richard Carlile, Joseph Johnson, James Moorhouse and John Knight stepped out of the carriage, while the crowd opened up to allow them to ascend a ladder onto the platform. At this point Hunt is recorded as querying the position of the hustings, insisting it would have been safer located on the other side of the field. Edward Baines, junior, of the Leeds Mercury, who had been present from about midday and on the hustings from about one o’clock, recalled Hunt appeared to be ‘out of temper’.81 In support, John Tyas, who was now also standing on the hustings, observed that the platform was inconveniently positioned, since each speaker would have to attempt to carry his voice across the immense crowd with the wind against him.82

With so many people pressing forward around the hustings, it was considered sensible to seat some of the Manchester Female Reform Society committee members in the barouche, including Elizabeth Gaunt, who was feeling unwell, while Mary Fildes and others were helped up onto the platform. Edward Baines observed that a number of young women ascended the hustings ‘to avoid the pressure of the crowd, which was very great at the time; one or two women had fainted from the pressure’.83 Richard Carlile described the meeting at this time as calm and orderly: ‘Hilarity’, he observed, ‘was seen on the countenances of all, whilst the Female Reformers crowned the assemblage with a grace, and excited a feeling particularly interesting.’84 Carlile’s hint that the presence of women helped maintain calm and decorum was echoed by John Smith, who ‘looked upon this as a sort of guarantee for the peaceable conduct of the men as to any heated expression; for I consider the presence of the ladies always chastens the company’.85 Smith later commented that Mary Fildes and her companions did not deserve the term ‘profligate Amazons’ which had been levelled at them.86

John Thacker Saxton had arrived on the hustings only recently, having already been to the Manchester Observer offices that morning along with James Wroe. One witness recalled that he was on the platform with a notebook and pencil to report on the proceedings.87 As the barouche party walked out onto the raised platform, signalling the moment everyone present had been waiting for, the music stopped. Joseph Johnson proposed that Henry Hunt take the chair, which, as Bamford noted, was ‘carried by acclamation’. Orator Hunt received another great shout as he walked to the front of the hustings and, removing his hat with appropriate solemnity, prepared to address the vast and expectant crowd spreading out into the distance before him.88

Located one hundred or so yards away, the Reverend Edward Stanley heard Hunt begin his address: ‘I could distinctly hear his voice, but was too distant to distinguish his words.’89 Edward Baines, standing a few feet behind Hunt, took down his speech using shorthand and added details from memory a few hours later. According to his notes, Hunt commenced: ‘Friends and fellow-countrymen, I must beg your indulgence for a short time, and beg that you will keep silence. I hope you will exercise the all-powerful right of the people in an orderly manner.’90 Unlike Stanley, John Smith, standing just twenty-five yards to the front of the hustings, appears to have no trouble hearing at all, as his later summary, consistent with that of both Baines and Tyas, confirms. Hunt told his hearers with some satisfaction that the week’s delay of the meeting had worked against the magistrates, as it had resulted in a much larger crowd on the day. He asked them all to keep order and to restrain anyone in the crowd who attempted to disturb the peace.91 This last was directed towards the troublemakers whom Hunt suspected of lurking within the crowd, with the encouragement of the police or authorities.

Stanley was still unable to hear what was being said, but recalled that Hunt ‘had not spoken above a minute or two before I heard a report in the room that the cavalry were sent for; the messengers, we were told, might be seen from a back window.’ Running swiftly to that window, Stanley ‘saw three horsemen ride off’.92 He then returned to his original station, ‘anxiously awaiting the result’.

What had caused the magistrates to request the presence of the cavalry? If Stanley could not hear what was being said on the hustings, then surely nor could William Hulton and his fellow magistrates in the room below. What could Nadin, Andrew and their special constables have reported back to them to create such alarm? Unless Hunt had incited the people to riot, or had used seditious language, there appeared to be no reason to arrest him, no need for the Riot Act to be read and, therefore, no need for the Yeomanry or military to be called upon to disperse the crowd. The magistrates may have been requesting that military forces be drawn closer to the field as a precaution. But Stanley’s memory of ‘anxiously awaiting the result’ suggests that a decision to use those forces, beyond a mere display of might, had already been taken.

William Hulton himself confirms this to be the case. He recalled that over the period prior to Hunt’s arrival, he had continued to receive sworn depositions and that ‘Many gentlemen stated to me, that they were greatly alarmed’.93 One declaration was signed, according to Hulton, by sixty people: he was ‘acquainted with a great many who signed it; They are men of the highest respectability.’94 By this time, Hulton says, ‘looking to all the circumstances, my opinion was that the town was in great danger.’95 One circumstance that ‘had great influence with me in signing the warrant’ was the noise in the crowd on Henry Hunt’s arrival, because the contingent accompanying Hunt’s procession was ‘a great accession of strength to the numbers already collected’,96 and the resulting thunderous roar confirmed the immense scale of the combined crowd which had by now gathered. William Hay later acknowledged the disturbing impression that Hunt’s arrival gave, yet he observes that ‘long before this, the Magistrates had felt a decided conviction that the whole bore the appearance of insurrection; that the array was such as to terrify all the king’s subjects, and was such as no legitimate purpose could justify. In addition to their own sense of the meeting, they had very numerous depositions from the inhabitants, as to their fears for the public safety’.97 In contrast, inevitably, to the statements of Samuel Bamford and John Smith, William Hulton was convinced that the sticks being carried by members of the crowd were there not for defence, nor to assist the elderly in walking, but for attack, and, he reiterates, they were raised against representatives of the civil and then the military power in an aggressive and intimidating manner.

Hulton noted the last deposition, by a Mr Owen, was received around the time that the barouche arrived alongside the hustings and Henry Hunt and his companions alighted.98 He also observed that the population of Manchester and Salford combined was (as of 1805) one hundred thousand – the lowest estimate for the numbers gathered on the field is fifty thousand, the figure Hulton himself quotes – and that within this large town were many shops and warehouses, all vulnerable to attack during any public disorder.99 William Hay considered it to be ‘one of the most tumultuous meetings he ever saw… he felt great alarm for the safety of the town; and in that view of the case, he thinks the Magistrates would have betrayed the trust reposed in them if they neglected taking means for the apprehension of the authors of that meeting’.100

It was the fear that property might be at risk – amplified by the genuine concerns of the townsfolk, given on oath – added to a deep nervousness at the sheer scale and ‘tumultuous’ nature of the meeting, that led the assembled magistrates to issue a warrant for the arrest of the ‘supposed’ leaders: Henry Hunt, Joseph Johnson, John Knight and James Moorhouse. Although William Hulton was unable to produce the warrant at the subsequent trials, a copy – or at least a document alleging to be a copy – does exist in the Home Office papers.101 It reads:

Lancashire to wit. To the Constables of the Township of Manchester in the county of Lancaster, and also to all other constables and Peace Officers, within the said County

Whereas Richard Owen hath this day made oath before us, his Majesty’s Justices of the Peace in and for the said County of Lancaster, that Henry Hunt, John Knight, Joseph Johnson and — Moorhouse, at this time (from a quarter past one-o-clock) have arrived in a car, at the area near St Peter’s Church, and that an immense mob is collected, and that he considers the Town in danger, and the said parties moving thereto. These are, therefore, in his Majesty’s name, to require you forthwith to take and bring before us, or some other of his Majesty’s Justices of the Peace in and for the said county, the bodies of the said Hunt, Knight, Johnson and Moorhouse, to enter into recognisances, with sufficient Sureties, as well for their personal appearance at the next general Sessions of Assizes to be holden in and for the said county… Given under our seals the 16th day of August in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and nineteen.

This version of the warrant indicates that the original was signed by all the magistrates present, including William Hulton, the Reverend William Hay, the Reverend Charles Ethelston, James Norris and Colonel Ralph Fletcher.

A note at the bottom of the page, in a different hand, reads, ‘Examined with the original this 14 day of Nov. 1819. Joseph Nadin W. Heslop’, which, inevitably, raises some questions as to its authenticity. However, such documentation – whether a true reflection of the reasoning at the time, or a subsequent justification – sets out the motivation for the arrests in accordance with the sworn depositions that the magistrates had received from respected townsmen. It was Hulton’s stated opinion that the gathering ‘did undoubtedly inspire terror in the minds of the inhabitants’.102

This offers an explanation, rather than a justification, for the issuing of the warrant – but not for summoning the Yeomanry Cavalry and military assembled around the area. This decision, according to William Hulton, was taken after the senior constables, including Joseph Nadin and Jonathan Andrew, expressed their fears of the consequences should they attempt to arrest Hunt et al. with only their several hundred assembled constables, without additional support. Andrew later declared that since ‘communication with the hustings was, at the time, cut off’, with the atmosphere already tense, ‘and knowing the state of the country’, he ‘would not have ventured his life; he should have thought it an act of madness to attempt it; in short, he refused to execute it without military assistance.’103 According to Nadin, he too declared that from ‘all he had seen that morning, he did not deem it practicable to execute the warrant without military aid’.104 Hulton apparently responded with surprise: ‘What! … not with all those Special Constables?’105 But Nadin and Andrew were adamant. Clearly now agreeing with them, Hulton sent two notes, one to Major Thomas Trafford, commander of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry, and his second in command, Captain Hugh Hornby Birley, stationed in Portland Street, and the other to Lieutenant Colonel Guy L’Estrange, overall commander of the combined regular military and Cheshire Yeomanry, ‘requiring them to come to the house where the magistrates were’. If any delay had occurred between the issuing of these two notes, it can only have been a matter of minutes. Hulton later stated that when he signed the letters he considered ‘the lives and properties of the people of Manchester were in the greatest danger; He took it for granted that the meeting in Manchester was part of a great scheme in the district, of the existence of which they had received the most undoubted information some time before.’106 He insists that he ordered the advance of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry ‘to save, and not destroy the lives of his fellow-creatures’.107

The loyal newspaper, the Manchester Chronicle, summarized the situation in the following manner:

The rebellious nature of the meeting, its numbers and threatening aspect, the warlike insignia displayed, the order of march and military arrangement, many of the Reformers having shouldered large sticks and bludgeons as representative of muskets, coupled with the depositions on oath of very many respectable inhabitants as to the consequences that must in their opinion unavoidably flow to lives and property from such an immense meeting, assembled under such influences; and the Magistrates’ own view of the whole of this tremendous scene – rendered it imperative to interfere. To have attempted it by the common means would have been preposterous, and could only have caused the loss of a great number of lives without a chance of completing the object.108

Throughout their recollections, the magistrates maintain a distinction between the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry, under their direct command, and the ‘military’. William Hay stated later that he agreed with Hulton that they should not ‘require military aid, if possible’, and that ‘they had nothing to do with the arrangements of the Military – that they most pointedly left to Colonel L’Estrange, he made all his own arrangements, judging he was the most competent person’.109 It does not seem to have occurred to anyone present that problems might arise from the fact that the combined troops, amateur and professional, were not under a single overall commander.

Once all the administration had been completed, Joseph Nadin walked back outside to join the special constables, warrant in hand. The plan was that when the cavalry appeared, the lines of special constables would pull back and make way for them to advance to the hustings and then, accompanied by the officers and with the crowd held at bay by cavalrymen, he, Nadin, would make the arrests.

In the usual sequence of events, the Riot Act would have been read out at this point. Its full title was ‘An Act for Preventing Tumults and Riotous Assemblies, and for the more speedy and effectual Punishing the Rioters’; once it had been read aloud to an assembly, the people had one hour to leave the area peacefully before the military were sent in to disperse them. William Hay had had the proclamation printed up and circulated to those magistrates attending in advance, and he states that it was read during the ‘interval between the Yeomanry coming up and while they were forming’.110 It fell to Charles Ethelston, with his well-rehearsed and booming baritone, to do the honours; William Hay described him as having ‘a remarkably powerful voice’.111 A powerful voice would indeed be required, as Henry Hunt could testify, if the announcement was to be heard over the crowd. It was usual to read word for word the proclamation as set out in the original act of 1714 – the year the first Hanoverian king, George I, ascended the throne of Great Britain:

Our Sovereign Lord the King chargeth and commandeth all persons, being assembled, immediately to disperse themselves, and peaceably depart to their habitations, or to their lawful business, upon the pains contained in the Act made in the first year of King George, for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies.

GOD SAVE THE KING112

Charles Ethelston later asserted that he had attempted several times to read the proclamation out on the ground itself; indeed he had hoped to deliver it on horseback but, in the commotion, his steed had disappeared along with his servant. In any case, ‘he found it could not be heard’. He therefore returned to a first-floor window in Mr Buxton’s house and tried again from there.113 William Hay recalled that Ethelston leaned so far out of the window that he ‘stood behind him, ready to catch his skirts for fear he might fall over’.114 It was this scene, ripe with satirical possibilities, that was later ridiculed in a print published by John Saxton.115 ‘When he drew back his head into the room, after having read the proclamation’, Hay told him, ‘Ethelston, I never heard your voice so powerful.’116

Not one witness who was not part of the civil power heard the Riot Act being read. James McKinnel, a salesman from Manchester, who was standing on the steps of the house, declared that ‘there was no particular noise to prevent him hearing it read; he heard nothing read from Mr. Buxton’s house; The Magistrates were in a room over his head, but he heard no such thing as the Riot Act read.’117 Edward Stanley, directly above, did not hear it either. William Hay, when asked about this specific point, replied that he ‘can’t say whether a person standing on the steps of Buxton’s house could hear it read, or from the room over that where he was; He cannot account for other persons’ organs.’118 It seems clear that no one present on the field was warned of what was coming.

The 15th Hussars, as Lieutenant William Jolliffe later recounted, had paraded in field-service order at around half past eight that morning. Two squadrons, led by Lieutenant Colonel L’Estrange and Lieutenant Colonel Leighton Dalrymple, had then been marched into Manchester at around ten o’clock.119 They dismounted in Byrom Street, a wide thoroughfare about a quarter of a mile to the west of St Peter’s Field, where they were joined by a squadron each of the Cheshire Yeomanry and the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry (the majority of the latter were still positioned in Portland Street to the east of the field). The cavalry, for speed, would be sent in first, with the infantry, the 88th Foot under Lieutenant Colonel McGregor in Dickinson Street (near the Quaker Meeting House) and the 31st Foot in Brazennose Street (just to the north), brought in if need be. The guns and Royal Horse Artillery under Major Dyneley were located to the southeast, out of sight of those gathered on the field.

Lieutenant Colonel L’Estrange and his assembled cavalrymen remained in Byrom Street for several hours. Throughout that period, while awaiting further orders, Lieutenant Jolliffe observed that ‘a solid mass of people continued moving along a street about a hundred yards to our front’. L’Estrange recalled that as Hunt was passing along Deansgate, parallel and just to the east of Byrom Street, he rode with Lieutenant Colonel Townshend, of the Cheshire Yeomanry, to see him: ‘When the carriage came up, Hunt, who either rose or was standing before, waved his hat, looked at them, then at the mob, and shouted; they also shouted, he supposed in defiance, from seeing them in uniform.’120 Given that this incident happened on Deansgate, it is possible that L’Estrange and his fellow officers happened to arrive as the barouche passed the Star Inn and therefore mistakenly took the defiance shown towards the magistrates, as recounted by John Tyas, to be directed at them. After observing the barouche move on, the officers returned to their men stationed in Byrom Street and waited.

In Mount Street, as he watched for the arrival of horsemen, the Reverend Edward Stanley noticed that a ‘slight commotion’ could be heard from within the large group, consisting mainly of women, standing on the raised ground on Windmill Street, behind the hustings. He believed this signalled the first sighting of the main contingent of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry, commanded by Captain Hugh Birley, numbering about sixty men and horses, arriving at the northeast corner of the field. He describes seeing people in this area, with their clear view across the field, jumping down and hurrying away. Unknown to those watching their arrival, the Yeomanry Cavalry had already claimed their first casualty. As they advanced from Portland Street and then along Cooper Street, eventually turning into Peter Street and onto the field, they had accidentally run down and mortally injured William Fildes – no direct relation to Mary – who was only two years old.121 Now the alarm was spreading swiftly through parts of the crowd, and Stanley heard cries of ‘The soldiers! The soldiers!’ All at once, the cavalry appeared ‘on a gallop, which they continued till the word was given for halting them, about the middle of the space’.122 William Elson, the farmer from Middleton, had lost sight of his three teenage children in the crowd* but, he remembered later, ‘I was not uneasy about them, as I knew they were acquainted with Manchester. I had no fear… till I saw the Yeomanry coming.’123 The bookseller James Weatherley, standing near the Quaker Meeting house, watched the troops arrive and noted that at their head was Edward Meagher, ‘an Irishman and Trumpeter… of bad character’.124 Nathan Broadhurst, an army veteran standing about eight yards from the hustings, described Meagher as ‘tall, thin, dark-complexioned’ and, distinctively, riding a piebald horse.125

The Yeomanry Cavalry moved down Mount Street and paused in front of Mr Buxton’s house, where Chief Constable Jonathan Andrew was now standing. He approached their commanding officer, Captain Birley, ‘and stated they had a warrant, and desired him to surround the hustings, in order that they might take the parties against whom they had the warrant’.126 Nadin recalled that on seeing the Yeomanry he ‘drew the Special Constables back to the house’ as planned, ‘to enable the Cavalry to advance’.127 Andrew, on foot, tried to keep ahead of the Yeomanry for as long as possible, as they moved forward to the hustings, but was prevented by the crowd and then the Yeomanry passed him.128

Nadin and Andrew would make no mention in their later testimony of the manner in which the Yeomanry Cavalry arrived on the field, nor how they then moved through the crowd, thereby creating the impression that their approach was orderly and without incident. The Manchester Chronicle considered the Yeomanry’s advance ‘was done in a steady and masterly style; but the Cavalry had not advanced many yards before they were assailed with heavy vollies [sic] of stones, shouts of defiance, and the most coarse and insulting language. Till thus assailed, no Yeomanry-man used his sword, each man having confined himself to waving it over his head.’129 This contrasts with most other witness accounts, including, as we shall see, that of William Hulton. Indeed, if the Yeomanry’s approach had been conducted in ‘a steady and masterly style’, how had they managed to knock down and kill William Fildes?

*

From his position in the crowd, Samuel Bamford watched Henry Hunt clear his throat. Suspecting there would be nothing new in the speeches, he started to move away from the field in search of refreshment, and recalled, as he did so, hearing a ‘noise and strange murmuring’ arising from the direction of St Peter’s Church. He stood on tiptoe to find out what was happening, but rather than seeing, as he expected, more people marching triumphantly onto the field, he saw a party of cavalry in blue and white uniforms ‘come trotting sword in hand, round the corner of a garden-wall, and to the front of a row of few houses, where they reined up in a line’.130 Bamford turned to a companion and said, ‘The soldiers are here… we must go back and see what this means.’ Someone nearby voiced the opinion that the presence of the Yeomanry was simply a precaution, in case trouble should occur on the field; not everyone considered an attack on the crowd to be inevitable. Bamford, however, was concerned, and he forced his way back through the throng towards the Middleton banners, his wife and his party.

Henry Hunt, standing at the front of the hustings, was midway through his opening salvo, his trademark white hat held in one hand, his other raised and punching the air in his usual manner. He was explaining how the postponement of the event had worked against the magistrates when, in the words of John Tyas, John Knight ‘whispered something into Mr. Hunt’s ear, which caused him to turn round with some degree of asperity to Knight, and to say, “Sir, I will not be interrupted: when you speak yourself, you will not like to experience such interruption.”’131 It is possible that Knight had seen the arrival of the Yeomanry and was attempting to warn Hunt. But the Orator, feeding off the intense expectation of the vast multitude, was building himself up towards his empowering message of hope and justice for all, and was understandably irritated by the disruption to his momentum. Hunt does not mention this incident, but recalls declaring that it was his ‘conviction that the orderly conduct of the people would deprive their enemies of all pretence whatever to interrupt their proceedings’. That interruption arrived nonetheless: ‘I had scarcely uttered two sentences, urging them to persevere in the same line of conduct, when the Manchester Troop of Yeomanry came galloping into the field.’132 The Yeomanry formed up in front of Mr Buxton’s house, and Hunt observed, ‘As soon as the military appeared, the people, (as is always the case under such circumstances) began to disperse and fly from the outskirts.’133

James Wroe later reported that at this point Hunt ‘broke off suddenly’, as the disruption appeared to be spreading, and then attempted to reassure the crowd: ‘turning around with a manner that showed him perfect master of the art of managing large assemblies, he explained to his friends, who were at a loss what to shout for, that it was only that “there was a little alarm manifested at the outskirts, and he gave the shout so to inspire confidence – that was all.”’134 According to Henby Andrews, Hunt’s servant, his master had encouraged the crowds to cheer the arrival of the military at meetings in Bristol and Spa Fields, and saw this as similar to these occasions.135 According to Hunt, the cheers ‘had the desired effect of restoring the confidence of the people, who did not, indeed, suspect it to be possible that the devil himself would have authorized the Yeomanry to commit any violence upon them.’136

After watching the Yeomanry advance about ten yards into the crowd, Edward Baines jumped down from the hustings and made his way through the crowd in the opposite direction to Mr Buxton’s house. He turned back to see Hunt ‘stretching out his arm’ and repeatedly urging the crowd to cheer and to ‘be firm’. Baines told Hunt later: ‘My impression was, that you merely wished the people to stand, and to prevent danger from their running away.’137 And he reiterated, ‘When you used the words “be firm”, you stretched out your arms, with your hands open and the palms down.’ At this time, Baines thought, the ‘people had not the appearance of disciplined troops, ready to protect Hunt or to fight for him, as occasion offered… My impression was, that the cheers were cheers of conscious innocence, confidently relying on the protection of the laws.’138

The chairman of the magistrates, William Hulton, had supposed, with some justification, that the cavalry as a whole – whether Yeomanry or Hussars – would appear on the field at the same time. In the event, it was the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry who arrived first ‘at a quick pace’ from the Mosley Street end of Mount Street and then formed in a line ‘under the wall of the magistrate’s house’. According to Hulton the crowd, in response, ‘set up a tremendous shout. They groaned and hissed, and those men who had sticks shook them in the air. I saw those sticks lifted up in a menacing manner.’139 Hulton noticed ‘a good many women’ among the crowd and ‘I heard the women particularly noisy in hissing and hooting the cavalry when they first appeared’.140 After Hunt encouraged the crowd to shout out, the cavalry brandished their sabres as a response. Bamford also witnessed this: ‘On the cavalry drawing up they were received with a shout, of good will, as I understood it. They shouted again, waving their sabres over their heads.’141 The Yeomanry then advanced, in Hulton’s opinion ‘at a trot, or rather prancing; the horses were fidgeting in consequence of the noise, and they were not in good order.’142 In fact, at this moment, as the Yeomanry started to move through the widened avenue between the special constables, one of those volunteers, John Ashworth, was knocked down and, as the Manchester Chronicle described it, was ‘killed dead on the spot’.143 This certainly suggests that there was some disarray in the Yeomanry’s advance and that they were moving too fast for Ashworth, like the wretchedly trampled William Fildes, to get out of the way.

Hulton, apparently unaware of either casualty, observed what he describes as the difficulties the Yeomanry were having in moving across the field, but added that he distinctly remembered seeing ‘stones and brick-bats flying in all directions. I saw what appeared to me to be a general resistance.’144 He returned to the throwing of stones several times in his evidence, observing it was a ‘matter of notoriety; The Field had been, before nine o’clock, cleared of a cart load of stones’, which meant that the missiles must have been brought intentionally by participants. This was supported by evidence given by the surveyor Worrall, who found ‘a cart load’ of such items when he returned to the field at three o’clock that afternoon, the inference being, of course, that they had been ‘brought some distance’ by members of the crowd.145 It is fair to say that, in a crowd this size, some troublemakers are inevitable. Casting doubt on Hulton’s testimony, however, the Reverend Edward Stanley denied having seen missiles being thrown at the Yeomanry and Constables. Given his commanding viewpoint, he believed, he would surely have noticed something so obvious.

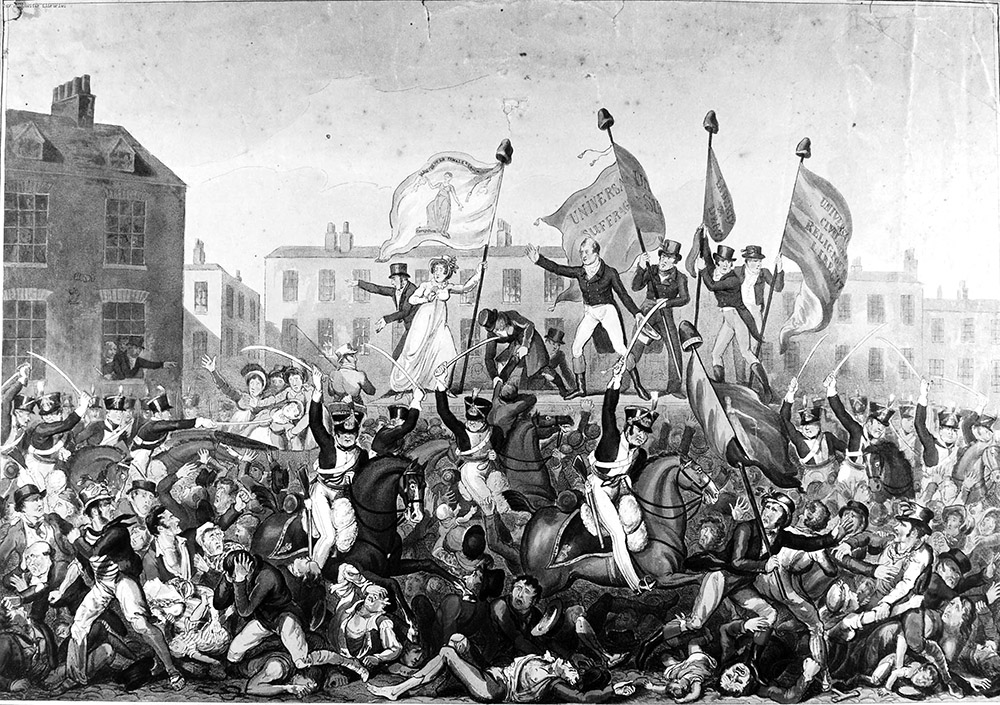

Despite Henry Hunt’s attempt to calm the situation, and before he could continue addressing the crowd, the order for the Yeomanry to advance had been given. Hunt looked on with disbelief as ‘they charged amongst the people, sabring right and left, in all directions. Sparing neither age, sex, nor rank.’146 The Yeomanry forced their way through the crowd towards the hustings, ‘riding over and sabring all that could not get out of their way’.147 John Tyas, still watching from the hustings, stated in his report that, despite extreme provocation, ‘Not a brickbat was thrown at them – not a pistol was fired during this period: all was quiet and orderly; as if the cavalry had been the friends of the multitude.’148 James Weatherley accuses Edward Meagher, leading the Yeomanry, of starting the attack on the crowd, ‘he was the first to begin the assault[,] he was four or five yards in advance of the others[,] he kept laying on the People right and left with his sword… he was like most of the others half drunk… he was a hot [tempered] Irishman’.†149 Richard Carlile, seeing the sudden advance of the Yeomanry, ‘appealed to the females on their fear of the approach of the military, and found them the last to display alarm’.150 John Smith, standing nearby, saw no resistance made to the Yeomanry’s advance, no missiles thrown or sticks brandished, but was surprised at the speed with which they moved through so dense a crowd. He recalled that some of the people around him cried, ‘What is to be done?’ while others judged the advance of the Yeomanry cavalry was merely to hear if any seditious expressions were being used by those on the hustings. They were not, at that point at least, fearful of the Yeomanry.151 The cotton spinner William Harrison, standing about ten yards from the hustings, confirmed Weatherley’s impression that the first of the Yeomanry Cavalry to arrive on the field ‘could hardly sit on his horse, he was so drunk; he sat like a monkey.’152

Samuel Bamford, in the midst of the crowd, watched the Yeomanry shout and brandish their sabres ‘and then, slackening rein, and striking spur into their steeds, they dashed forward, and began cutting the people’.153 He shouted for those around him to ‘Stand Fast’ and a cry repeating the phrase rose up from among them. Bamford noted the Yeomanry were ‘in confusion’, having great trouble, as he recalled, forcing their way through so great and dense a crowd, who, obviously, had nowhere to run. In terror, frustration or glee – who can say? – the Yeomanry’s ‘sabres were plied to hew a way through naked held-up hands, and defenceless heads; and then chopped limbs, and wound-gaping skulls were seen; and groans and cries were mingled with the din of that horrid confusion’. Bamford heard shouts of ‘For shame! for shame!’ and ‘Break! break! they are killing them in front, and they cannot get away.’ He then describes a strange momentary suspension of action, ‘a pause’, as if a spell had been cast, or a collective deep breath had been slowly drawn, which was then quickly followed by ‘a rush, heavy and resistless as a headlong sea; and a sound like low thunder, with screams, prayers, and imprecations from the crowd-moiled, and sabre-doomed, who could not escape.’154

From his position in Mount Street, Edward Stanley too saw that the Yeomanry had halted on the field ‘in great disorder’. Those standing with him – Stanley does not say who – attributed the confusion ‘to the undisciplined state of their horses, little accustomed to act together, and probably frightened by the shout of the populace, which greeted their arrival’. Henry Hunt, on sighting the Yeomanry, ‘pointed towards them and it was clear from his gestures that he was addressing the mob respecting their interference. His words, whatever they were, excited a shout from those immediately around him, which was re-echoed with fearful animation by the rest of the multitude.’ As this shout subsided, ‘the cavalry, the loyal spectators, and the special constables, cheered loudly in return, and a pause ensued of a minute or two.’155 The pause might suggest that neither side really understood the meaning of the cheers directed at them – were they expressions of friendship or aggression? Joseph Wrigley was clear on this matter. Regarding the crowd, ‘I thought they meant to show that they regarded them as friends; and I understood the soldiers to return it with the same meaning.’156 Nathan Broadhurst, the army veteran, similarly believed the crowd cheered in friendship: ‘I joined in the cheers, and I know I did it with that feeling.’157

Stanley provides this version of events:

An officer and some few others then advanced rather in front of the troop, formed, as I before said, in much disorder and with scarcely the semblance of line, their sabres glistened in the air, and on they went, direct to the hustings. At first, i.e., for a very few paces, their movement was not rapid, and there was some show of an attempt to follow the officer in regular succession, five or six abreast; but… they soon “increased their speed,” and with a zeal and ardour which might naturally be expected from men acting with delegated powers against a foe by whom it is understood they had long been insulted with taunts of cowardice, continued their course, seeming individually to vie with each other which should be first.158

Special Constable Robert Hughes claimed that as Hunt pointed towards the Yeomanry, he shouted ‘there are your enemies coming’ and that he referred to the Yeomanry in insulting terms, as ‘blood-suckers’ and ‘feather-bed soldiers’.159 Such language was not Henry Hunt’s style, however, and several far more objective witnesses had testified to the contrary, so this ‘evidence’ can be dismissed as an attempt to blame Hunt for inciting the crowd to attack the Yeomanry. Yet others listening, most notably the special constables standing nearby, had already taken Hunt’s instruction to the crowd to curb the activities of troublemakers as being directed at themselves and then at the Yeomanry, rather than at agents provocateurs.

The Yeomanry pushed and slashed through the crowd, injuring constables as well as demonstrators. They eventually arrived at the hustings where, as Stanley phrases it, ‘a scene of dreadful confusion ensued’.160 Nathan Broadhurst described how, as the cavalry approached, Henry Hunt ‘asked them what they wanted’, at which one of the cavalrymen answered that he had a warrant against him. This was not strictly true, since it was Joseph Nadin who held the warrant, and the Yeomanry had been called in to assist him. According to Broadhurst, Hunt declared ‘he would submit to the civil, but not the military power’, at which point Nadin and another constable arrived on the hustings, arrested Hunt ‘and pulled Mr. Johnson off the hustings by the legs’.161 General chaos resulted, during which Broadhurst says he was kicked off the platform.162

John Tyas later reported in The Times:

the officer who commanded the detachment went up to Mr. Hunt, and said, brandishing his sword, ‘Sir, I have a warrant against you, and arrest you as my prisoner.’ Hunt, after urging the crowd to remain calm, turned round to the officer and said, ‘I willingly surrender myself to any civil officer who will show me his warrant.’ Mr. Nadin… then came forward and said, ‘I will arrest you; I have got informations upon oath against you,’ or something to that effect.

The Yeomanry officer then tried to arrest Johnson, who, like Hunt, requested a civil officer. At this point Chief Constable Jonathan Andrew stepped forward. Tyas writes that Johnson and Hunt ‘leaped from off the waggon, and surrendered themselves to the civil power. Search was then made for Moorhouse and Knight, against whom warrants had also been issued. In the hurry of this transaction, they had by some means or other contrived to make their escape.’163 Nadin confirms that neither Knight nor Moorhouse was on the hustings at that point.164 Both were arrested subsequently, Knight at his own home in Hanover Street and Moorhouse at the Flying Horse Inn.165

John Tyas then states that from ‘that moment the Manchester Yeomanry Cavalry lost all command of temper’.166 He describes how John Saxton, still standing on the hustings, was approached by two Yeomanry cavalrymen: ‘There’, said one of them, ‘is that villain Saxton; do you run him through the body.’ ‘No,’ replied the other, ‘I had rather not – I leave it to you.’ The first then lunged at Saxton and, according to Tyas, it was only because he turned aside quickly that the blow did not kill him. ‘As it was, it cut his coat and waistcoat, but fortunately did him no other injury.’ Tyas continues, ‘A man within five yards of us in another direction had his nose completely taken off by a blow of a sabre; whilst another was laid prostrate, but whether he was dead or had merely thrown himself down to obtain protection we cannot say.’ Eventually, realizing that everyone present was now in danger of injury or worse, Tyas offered to give himself up to a cavalryman, declaring that he was only there to report on the proceedings. The cavalryman cried, ‘Oh! oh! You then are one of their writers – you must go before the Magistrates,’167 and Tyas was promptly arrested. James McKinnel, still watching from the steps of Mr Buxton’s house, saw the Yeomanry surround the platform ‘and immediately after he saw the flags and banners falling from the hustings’.168 Such items were now trophies to be seized and most destroyed.169

In the confusion Samuel Bamford, anticipating the seizure of the banners, had shouted to his companions holding the Middleton colours to break the flag-staves and hide the cloth. The blue banner was quickly hidden – it is the only one to have survived, thanks to Bamford’s quick thinking – but Thomas Redford, ‘who carried the green banner, held it aloft until the staff was cut in his hand, and his shoulder was divided by the sabre of one of the Manchester yeomanry’.170

Nathan Broadhurst also quotes one of the cavalrymen, as the troopers were sabring the crowd, crying, ‘Damn you, I’ll reform you – You’ll come again will you?’ and another’s grim observation, ‘I’ll let you know I am a soldier, to-day.’171 Perhaps the latter was a reference to the articles in the Manchester Observer the previous month, ridiculing the ‘stupid boobies of yeomanry cavalry in the neighbourhood’.

Despite the pandemonium engulfing the entire field, witnesses perceived that the cavalry’s attacks, rather than being random, had a discernible focus. It seemed that women were being targeted, many of whom, like Mary Fildes and Susannah Saxton, were dressed distinctively in white. Mrs Fildes is recorded in one source as having been ‘much beat by Constables & leaped off the hustings when Mr Hunt was taken’.172 Another source describes her as falling from the hustings, her dress catching on a nail; as she tried desperately to free herself, she was cut across her upper body by a member of the Yeomanry Cavalry.173 Mary Fildes survived this brutal attack, but, according to one source ‘was obliged to absent herself a fort night to avoid imprisonment’.174 Nor did it subdue her determined support for parliamentary reform and the rights of women, deemed so abhorrent by her attacker and his superiors. Richard Carlile, still on the hustings, also saw that women appeared to be ‘the particular objects of the fury of the Cavalry Assassins’.175 He describes a woman standing near him, holding an infant, being sabred over the head, ‘her tender offspring DRENCHED IN ITS MOTHER’S BLOOD’. Another woman, he states, was stabbed with the point of a sword in her neck, while others were sabred ‘in the breast’.176 Carlile’s famous print of this scene, dedicated to Henry Hunt and the female reformers, depicts a woman located in the barouche falling back into the arms of a companion while a member of the Yeomanry thrusts a sabre’s point between her breasts.

The Peterloo Massacre by George Cruikshank, 1819.

(Manchester Central Library / Bridgeman Images)

Other women were casualties of the general brutality displayed by the Yeomanry Cavalry. Edward Stanley remembered that ‘On the commencement of the charge’ some stragglers ‘fled in all directions; and I presume escaped, with the exception of a woman who had been standing ten or twelve yards in front; as the troops passed her body was left, to all appearance lifeless; and there remained till the close of the business’.177

From his high viewpoint, Stanley continued to observe the frenzied scenes around the hustings:

The orators fell or were forced off the scaffold in quick succession; fortunately for them, the stage being rather elevated, they were in great degree beyond the reach of the many swords which gleamed around them. Hunt fell – or threw himself – among the constables, and was driven or dragged, as fast as possible, down the avenue which communicated with the magistrates’ house; his associates were hurried after him in a similar manner. By this time so much dust had arisen that no accurate account can be given of what further took place, at that particular spot.178