‘The man in the moon’

On the evening of 16 August the Reverend William Hay wrote his report to Lord Sidmouth. He would soon journey south to London to give a further account in person. Replying to this initial report on the 18th, however, Lord Sidmouth praised the ‘deliberate & spirited manner in which the Magistrates discharged their arduous and important duty on that occasion’ and told Hay that he had ‘had great pleasure in representing their mer[i]torious conduct to His Royal Highness the Prince Regent. I do not fail to appreciate most highly the merits of the two corps of Yeomanry Cavalry, and the other Troops employed on this service.’1 On the same day, in response to Sir John Byng’s letter enclosing Lieutenant Colonel L’Estrange’s brief account written on the evening of 16 August,* Lord Sidmouth commended the conduct of the troops, including the Yeomanry, ‘no part of which is more eminently deserving of approbation than the Forbearance & moderation with which they sustained the insults unwarrantably directed against them on this trying occasion’.2

Light years away from the turmoil and bloodshed on Manchester’s streets, the Prince Regent was aboard HMY Royal George, termed a yacht but in reality more of a ship, which had been launched in 1817, the year of the failed blanketeers’ march. In August 1819 he had been having a perfectly splendid time cruising around the Isle of Wight, giving sumptuous dinners on board, ‘served on a new service of china, ornamented with naval emblems, made expressly for use in the yacht’, as The Times reported. Among the toasts given by His Royal Highness, the first was to ‘The King’, which, the report continues, was pronounced ‘with evident feelings of strong filial affection and attachment’. Given their fraught relationship, this is difficult to imagine. The next was to ‘The Duke of Wellington and the Heroes of Waterloo’.

On Saturday 14 August, Commodore Sir George Collier, recently returned from the coast of Africa, had delivered to the yacht ‘a fine turtle, weighing about 6 cwt, for his Royal Highness’s gracious acceptance’.3 On the 16th, the yacht had sailed to the Hampshire coast, where the Prince Regent was to dine with Lord Cavan at Eaglehurst that evening. As he and his party disembarked, they were ‘saluted by huzzas from the crews of an immense line of yachts and pleasure vessels, and from an innumerable throng of yeomanry and peasantry on the Cliffs, all attracted to witness the landing of the Prince Regent on the New-forest shore’. He had already declared his intention to continue his maritime jaunt for another two weeks. His short visit to Weymouth on 19 August would be followed by a quick excursion to the Channel Islands. In the same column as this report, on 21 August, The Times printed word for word the address ‘To Henry Hunt, Esq’ from the Manchester Female Reform Society, which was ‘to have been presented… on Monday last, had not the meeting been so suddenly dispersed by the irruption of the military’.4 The newspaper had by now, of course, carried the report from John Tyas, detailing the terrible events on St Peter’s Field.

In a brief interruption to the Prince Regent’s holiday, Lord Sidmouth was commanded to convey His Royal Highness’s reactions. Sidmouth duly wrote to the Lords Lieutenant of Lancashire and Cheshire on 21 August, announcing that he had been asked to express to the magistrates ‘the great satisfaction derived by His Royal Highness from their prompt, decisive, and efficient measures for the Preservation of the Public Tranquillity’, and to ‘signify to Major Trafford [and] Lt Col. Townsend His Royal Highness’s high Approbation of the support and assistance to the Civil Power afforded upon that occasion by himself and the officers, non commissioned officers, and Privates of the Corps serving under his command’.5

In the storm of recriminations which engulfed the magistrates as news of the massacre emerged, William Hulton wrote a desperate letter to the Home Office, requesting permission to publish Lord Sidmouth’s letter of 18 August to William Hay, to show the world that they had the Home Secretary’s full support. In customary style, having had the time and information to appreciate fully what had happened in Manchester, Henry Hobhouse responded:

As Lord Sidmouth’s letters of Saturday last to the Earls of Derby and Stamford conveyed the most gracious appreciation of H.R.H. The Prince Regent, of the conduct of the Magistrates at Manchester, and expressed the great satisfaction which His Royal Highness had derived from their prompt, decisive, and efficient measures to preserve the public Tranquillity, which must be of far greater value than any thing only proceeding from Lord Sidmouth himself; His Lordship presumes that it can no longer appear to the Magistrates to be of any consequence to give Publicity to His letter of the 18th instant; and His Lordship would accordingly prefer that it should not be published. But His Lordship sees no objection to a Publication of His letter of the 21st.6

It was thus the Prince Regent’s response, delivered by Lord Sidmouth, which was published, rather than the Home Secretary’s own opinion. The Manchester Observer included it in their edition of 28 August, with an adjacent editorial comment discussing Sidmouth’s communication of the Prince Regent’s ‘satisfaction’ and ‘high approbation’ for the ‘most wanton effusion of human blood which ever disgraced the English name and nation!’ The editor ‘must believe’ – otherwise how could it be explained – that the Prince Regent was, in reality, ignorant of these ‘butcheries’ and had been deluded by misinformation ‘to protect the Magistracy in unconstitutionally employing a military force without first trying the efficiency of the civil power to disperse the Meeting’. The right of the people to assemble had been clearly set out by Henry Hunt and others, so far differing from Lord Sidmouth’s view ‘as to make them think his Lordship is in the habit of going to sleep with his eyes open’. The editorial concludes, adapting lines from Shakespeare’s Hamlet: ‘let the abettors of the corruptionists “paint and patch their atrocities an inch thick, to the complexion of murder they must come at last, and that most foul and most unnatural”’.7

In reaction to the events in Manchester, the radical writer and bookseller William Hone produced a bitingly satirical pamphlet entitled The Political House that Jack Built, using the same rhythm and repetition as the Manchester Observer’s poem ‘PETER-LOO’, in which he described the Prince Regent as

A dandy of sixty who bows with a grace,

And has taste in wigs, collars, cuirasses and lace;

Who, to tricksters, and fools, leaves the State and its treasure,

And, when Britain’s in tears, sails about at his pleasure.8

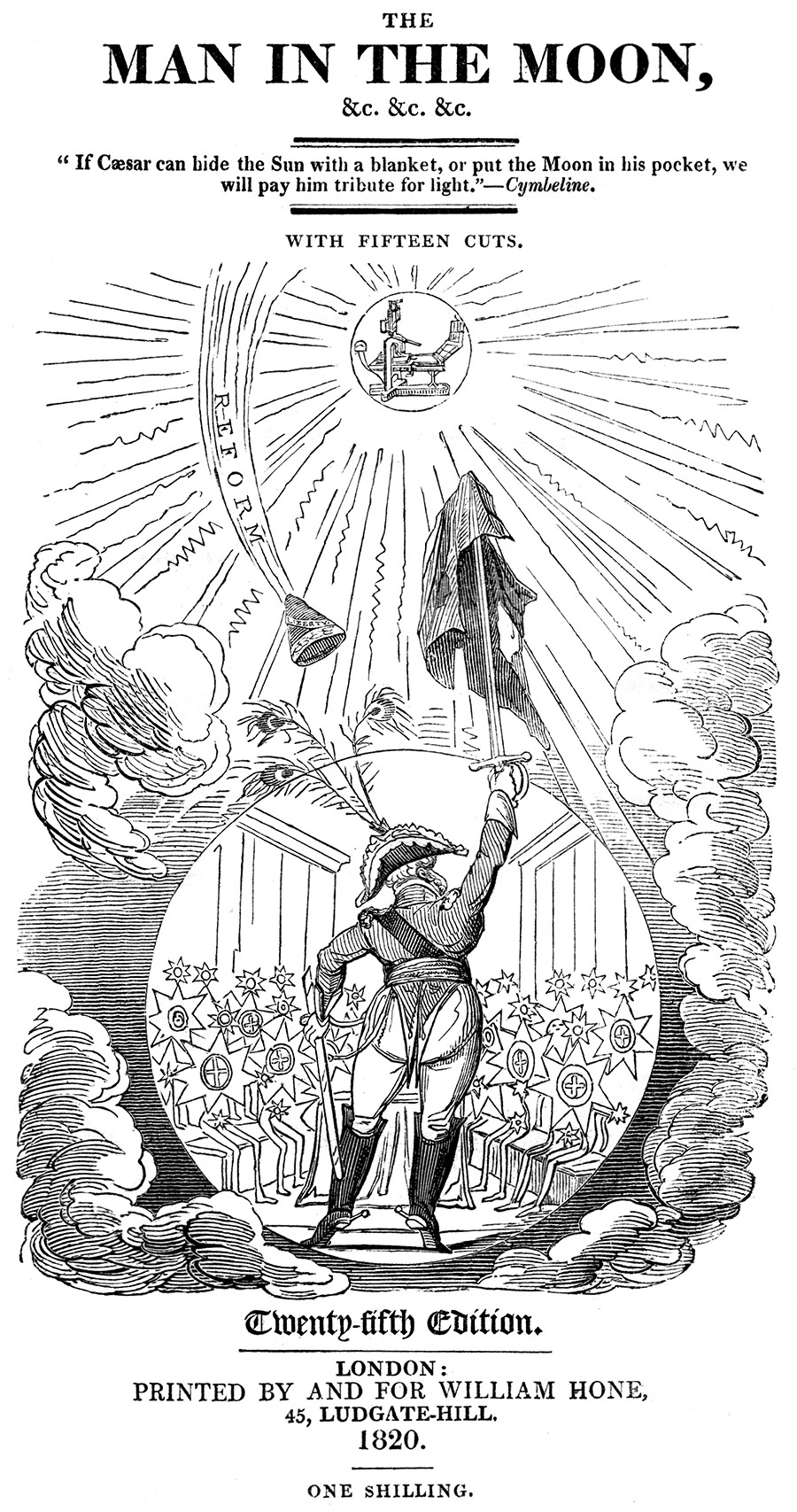

Soon after, Hone would publish another pamphlet lambasting the prince, this one fittingly entitled ‘The Man in the Moon’.

* L’Estrange’s account is broadly factual until he states that ‘some of the unfortunate People who attended the meeting have suffered, some from Sabre Wounds, and others from the Pressure of the Crowd’.