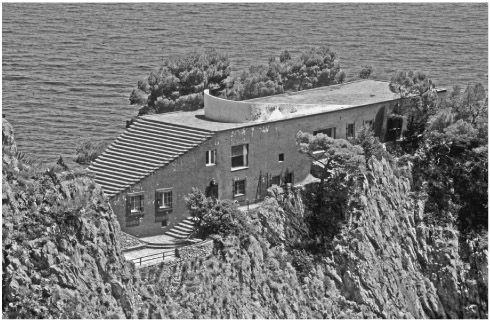

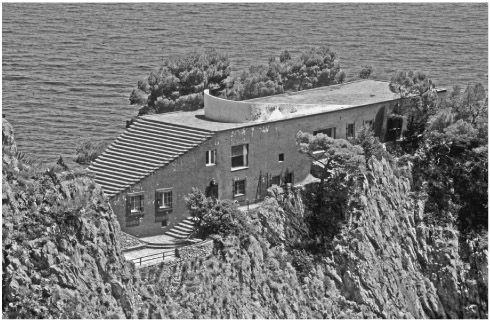

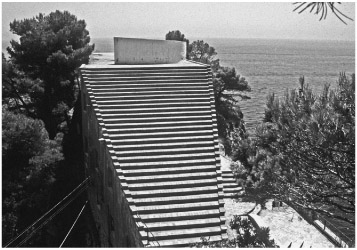

Figure 1.10.1 The Malaparte Villa, Capri, perched on its cliff above the Mediterranean, used as the setting for Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 Le mépris

Source: Photograph by Russell Light

As Vladimir Nabakov once wrote, it is not the conclusion of the story but how we get there that interests us. In the case of Ulysses, the saga of his wanderings, a monumentally frustrated return from Troy to Ithaca, took 20 years. It is a journey that functions as a sort of twelfth-century BC ur-journey template for all subsequent journeying, dictated by the blind rhapsode, to ‘alphabet adaptors’ in the eighth-century BC. It marks a transition, a phase change from oral (bardic) to written narrative – ur-text as well as ur-journey. As topographical description of the unknown coasts and peninsulas of the western Mediterranean, The Odyssey can be read as a preliminary exploration, preceding the seventh-century Greek colonisation of southern Italy: Ulysses as Captain Cook in felt cap (Pilos, his tag).

Homer’s Odyssey also served as the navigational chart for James Joyce’s 24-hour journey across Dublin. Joyce’s 1922 text is Ulyssean through its corporeal signifier, Bloom, who opens up the world: he blooms, in a commodious unfolding of alternative words and worlds.

Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 classic Le mépris (Contempt), a colour-coded film noir, also unfolds around the Odyssey narrative. It was shot in the heroic setting of Curzio Malaparte’s Capri villa, as backdrop protagonist (Figure 1.10.1). Appropriately, the actual Siren Rocks, the Galli, are visible from the mythological stage of the villa’s deck-like roof. As the film unfolds, characters slip in and out of various Homeric guises: Brigitte Bardot turns from Kalypso into Penelope, from black wig to blond bombshell, as she traverses her marital quarters, asking ‘where is the man I married’. Ultimately, she also becomes a siren as she swims off, naked, in the direction of the Galli. The German cultural theorist Friedrich Kittler has suggested that, in our media age, that of Hollywood, sirens no longer sing: instead, they abandon their bikinis. Michel Picoli, Bardot’s scriptwriter husband is, like Ulysses, held captive by the nymph Kalypso’s spell, but, in a cathartic homecoming, he reverts to the role of author (Homer). Fritz Lang plays himself, the famous film director, role-jumping at one point into the persona of the Emperor Tiberius, questioning, from the cliffs of Capri, the abandoned Penelope’s fidelity. In the final scene, Godard himself appears on camera, calls for silence and, with Lang, assumes joint command of the set, of the deck of the Villa Malaparte and its wide horizon.

The media status of the Capri villa is both catalyst and locus of transition for symbolic transfers; Curzio Malaparte himself metamorphosed from his original name, Kurt Sickert, to his pseudonym and enlarged status as author of what he referred to as ‘A house like me’.

This was taken up as the title of Michael McDonough’s 1999 book, which builds on the Villa Malaparte myth with an anthology of echoes: ‘A house like me . . . and me . . . and me . . . and me’.1 The list of mimetic Malaparte egos, all professing a strong associative yearning for the Capri cliff-hugger, includes Bruce Chatwin, Karl Lagerfeld, Tom Wolfe, Philippe Starck, Robert Venturi, John Hejduk, Steven Holl, Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves, Mario Botta, Ettore Sottsass and Arata Isozaki. The last offers us a transcultural interpretation of the name Malaparte, reading it as ‘bad part’, a counter-figure to a healthier Bonaparte and analogous to the Japanese mythological figure of Onamaru – Ogre Boy.

Figure 1.10.1 The Malaparte Villa, Capri, perched on its cliff above the Mediterranean, used as the setting for Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 Le mépris

Source: Photograph by Russell Light

Alberto Moravia, Capri resident and author of the original Le mépris storyline, said of Malaparte, ‘I never believed a word he said, even when he was telling the truth’. Ulysses, the guileful trickster, also scraped through with mimicry, cunning and storytelling. There is academic controversy about how much influence the architect Adalberto Libera really exerted on the design of the Malaparte villa: he obtained the building permit certainly, but, when General Rommel passed by on his way to the African Front and enquired if the house was built or bought, Malaparte answered, ‘the severe cliffs of the Matromania, the giant rocks of the Faraglioni, Penisola Sorentina, the blue Amalfi Beach, the shores of Paestum shining behind it, all these scenes are what I designed’.

The Ulysses role, of journeyman, suffering hero, adaptive trickster, may provide an analogous role model for today’s ‘star architect’ – journeying to the end of the world, to the underworld even, to Troy to construct a horse, to China to construct a new city, a stadium, a TV station. What did Ulysses construct along the way: a horse, a raft and a bed? From these three modest products we could assume that, like Daedalus or Hephaestus, he was adept in ‘techne’ – the act of making wondrous objects to overcome the disorder of the world, objects embodying ‘metis’, the inanimate becoming magically alive, not representing but reproducing life.

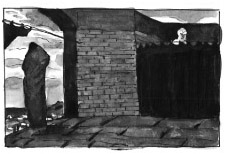

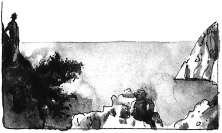

The Malaparte villa has no clear counterpart in the Odyssey narrative, except perhaps the deck of Ulysses’s ship, which he lost soon after negotiating the Siren Islands and surviviving the Maelstrom. The next 7 years he spent on the island of Ogygia (Gozo), captive under the spell of the immortal nymph Kalypso, Atlas’s daughter – a sex slave in today’s media jargon. We see them both depicted in Arnold Böcklin’s painting Odysseus und Kalypso of 1882 (Figure 1.10.2). Ulysses scans the horizon, suffering, homesick, wrapped in a dark cape, his back turned to the naked seductress, who sprawls daringly across a sensuous red cloth thrown over barren rocks. The same soulful figure we find again in De Chirico’s painting The Enigma of the Oracle of 1910, a symbolist homage (Figure 1.10.3), a silhouette migration to a high balcony overlooking a distant Aegean city. Perhaps this is also Ulysses, now back in Greece, where De Chirico spent his childhood. De Chirico is paying homage to his mentor Böcklin and to Nietzsche, who wrote, ‘we suffer to provide the poet with his material’ (‘wir leiden (um) der dichter Stoff zu liefern’). The critic Beatriz Colomina once wrote that the function of building architects is to provide objects (subjects) for the critic to dissect (an echo of Nietzsche). Feasting in the Hall of King Alkínoös, Ulysses sheds tears on hearing the blind rhapsode Demódokos sing of his Trojan feats (The Iliad). The Odyssey reports that:

He sat on the rocky shore

and broke his own heart groaning, with eyes wet

scanning the bare horizon of the sea

. . .

O, I long for home, for the sight of home.2

Figure 1.10.2 Arnold Böcklin’s 1882 painting Odysseus und Kalypso, redrawn by Peter Wilson after the original in the Kunst Museum, Basel

Figure 1.10.3 Giorgio de Chirico’s painting The Enigma of the Oracle, 1910, redrawn by Peter Wilson

Figure 1.10.4 Ulysses stranded on the rocky shore, drawn after Le mépris, by Peter Wilson

Böcklin presents a psycho-gram of strained relations. His setting of Odysseus and Kalypso is more like ‘a sea cave where nymphs had chairs of rock and sanded floors’ (Homer’s description of Thresias)3 than Kalypso’s actual domestic arrangements. These were somewhat more commodious than Böcklin’s version, as observed by Hermes arriving with Zeus’s command for the soft-braided nymph to release her captive:

Upon her hearthstone a great fire blazing

scented the farthest shores with cedar smoke

. . .

A deep wood grew outside, with summer leaves

of alder and black poplar, pungent cypress.

Ornate birds rested and stretched their wings

. . .

Around the smooth walled cave a crooking vine

held purple clusters under ply of green;

and four springs bubbling up near one another

shallow and clear, took channels here and there

through beds of violets and tender parsley.4

The home of the nymph offers sensuous abundance, a Vitruvian comoditas, not present in Böcklin or in the sculptured Ogre Boy stronghold of the Malaparte villa. Another incessant Mediterranean traveller, the one-time Capri resident Bernard Rudofsky, published in the March 1938 Domus, ‘A country house for an open minded woman’, located on the island of Procida adjacent to Capri (Figures 1.10.5–1.10.7).5 Although unrealised, it followed on from two earlier coastal houses, designed in partnership with Luigi Cosenza, the Villa Campanalla Positano and the Casa Ora.6 Rudofsky was an incessant traveller and a lifelong champion of the Mediterranean lifestyle, which he saw as both a healthy and honest version of the modernist aesthetic and an earthy alternative to northern abstraction. The sensuality of Kalypso’s cave would not be out of place in his influential book Architecture Without Architects, a protest against functionalist hegemony.7 The house on Procida was almost contemporary with the Villa Malaparte: it was published in the same month that Adalberto Libera submitted the initial site plan, titled Progetto di Viletta di Proprieta del Sig. Curzio Malaparte, for a building permit – described by Libera’s biographers, Francesco Garofalo and Luca Veresani, as, ‘granted quickly and discreetly through an influential intervention’. The approved design was for an elongated, rectangular building with rusticated base and an upper living room at the outer end of the roof terrace. Perhaps Libera was distracted by the Esposizione Universale Roma Palazzo dei Congressi construction (he had won the prestigious competition in 1937), or perhaps his assertive client stepped in with disputed additions, such as the tapering staircase (Figure 1.10.8), often referenced to the Little Church of the Annunziata on Lipari, in front of which Malaparte was photographed in exile. In either case, work progressed slowly, and may or may not have been influenced by Rudofsky’s publications. A gender-specific dialectic pairs these built and unbuilt manifestos, the harsh metaphysical poetry of the male egoist clifftop villa finding its counterpart in the commodious atrium house projected by Rudofsky for his future wife Berta Doctor. Both mediate between an idealised occupant and the world, metaphorically using geometry to locate a microcosm of the specific, of individual experience, within the macrocosm (Heidegger’s fourfold of earth, sky, mortals and immortals). Rudofsky’s

Figure 1.10.5 Bernard Rudofsky’s evocative image of the villa on Procida, published in Domus, March 1938, redrawn by Peter Wilson

Figure 1.10.6 (above, top) The essential presence of the courtyard – conceptual drawing of the villa on Procida, redrawn by Peter Wilson

Figure 1.10.7 (above) Rooms of the villa with Rudofsky’s allegorical representation of daily life rituals, redrawn by Peter Wilson. The floor of the lady’s bedroom is all bed; the music room has an afternoon divan

Figure 1.10.8 Villa Malaparte, the external steps leading to the roof terrace

Source: Photograph by Russell Light

atrium composition (although designed by a man) is a woman’s space, prioritising a sensuality not dissimilar to that of Kalypso’s place.

For the Libera–Malaparte villa, windows are emblematic, providing views of the majestic Faraglioni rocks and introducing a surrealistic sense of vertigo. Mysterious and sublime large-format glass rectangles (today’s signature of Swissness) conjure simultaneously both danger and refuge, prisons also for the cast of Le mépris who flutter before them, caged within their cinematically prescribed roles (Figure 1.10.9). Conversely, Rudofsky argued, ‘Ancient houses had few if any windows. The only opening deemed appropriate for a room was a door, because it was a passageway’; also, as if in affirmation of his manifesto’s counterpart, ‘stairs don’t belong in a country house. Stairs are the most important requirement of monumental architecture; they should be constructed outside as elements of landscape’. His was an argument for the Pompeian house format – a string of rooms arranged around an open central atrium (Fig 1.10.5–1.10.7). His theme is movement, daily domestic trajectories, from room to room, from within to without. Familiar functional codes are rescripted in his plan, which not only depicts the physical enclosure of walls, but also, with a radical and unconventional graphic invention of sketched allegorical figures, a prescribed choreography of each room, is the template of a sensuous Mediterranean lifestyle (Figure 1.10.7).

Swiftly she turned and led him to her cave,

and they went in, the mortal and the immortal.

He took the chair now left empty by Hermes,

where the divine Kalypso placed before him

victuals and drink of men, then she sat down

facing Ulysses, while her serving maids

brought nectar and ambrosia to her side.8

Such vignettes extend outside: a dog beside the lady of the house, relaxing in a hammock or galloping on horseback across the sand of the adjacent beach. Rudofsky’s isometric sketch of this arrangement (Figure 1.10.5) is one of Mediterranean modernism’s iconic images – advocating an epicurean and sensual ‘comoditas’ (as did Le Corbusier’s sketched vignettes). Gio Ponti, who provided Rudofsky with his Domus platform, once stated, ‘The Mediterranean taught Rudofsky and Rudofsky taught me’. The two collaborated on a subsequent 1938 San Michele Hotel design – a spontaneous hotel, a cluster of houses/rooms to be scattered and invisible in the woods above a precipitous Capri cliff. Paths from the rooms (room of the angels, room of the doves, room of the sirens) converge at the village centre, ‘the residence of the gentleman who manages the place’. Arriving guests leave their clothes in a closet and are equipped with sandals, hats and other necessaries designed by the architects.

At this moment, Rudofsky fled Fascist Italy for South America, Japan and New York, his own lifelong Odyssey, which left a trail of exhibitions and open houses, disseminations of the Capri code, unfolding into luxurious green terraces. These include the 1939 Arnstein or Frontini houses in São Paulo and the skeletal garden framework of the Nivola house, Amagansett, Long Island, NY. In September 1950, Le Corbusier also visited this, the house of the artist Constantino Nivola, leaving his usual tag – a mural unfolding over two living-room walls (as he had at Eileen Gray’s Mediterranean-facing Cap Martin villa). On 28 September 1950, Le Corbusier took a lift back to New York with Nivola’s neighbour, Jackson Pollock – ‘A better driver than painter’, commented Le Corbusier. Pollock subsequently drove himself into a tree, no joyous homecoming for a modern arts Agamemnon.

Figure 1.10.9 (left) ‘The cast caged within their cinematically prescribed roles’, drawn, after Le mépris, by Peter Wilson

Figure 1.10.10 (right) ‘Picoli and Ulysses pass either side of the rooftop wall’, drawn, after Le mépris, by Peter Wilson

Malaparte, like Ulysses, was an exile. Sent by Mussolini to the islands of Lipari (and later Ischia), he wandered and recorded war-ravaged Europe in his magnum opus, Kaputt (1943), before finally coming home to his Capri villa. Like Ulysses, his trajectory was a Gaussian random walk, his fate displacement, his goal return. Ulysses’s return was watched over and orchestrated, as always, by Pallas Athena; it began with the construction of a raft. He:

fell to chopping . . . twenty tall trees were down. He lopped the branches, split the trunks . . . drilled through all the planks, and then drove stout pins to bolt them. . . . He made the decking fast to close set ribs before he closed the sides with longer planking, then cut a mast pole. . . . He drove long strands of willow in all the seams to keep out the waves. As for a sail, the lovely Nymph Kalypso brought him a cloth so he could make that, too. Then he ran up his rigging – halyards, braces – and hauled the boat on rollers to the water.9

Seventeen days he sailed, until vindictive Poseidon, angered that other gods had deemed to end Ulysses’s exile, churned the deep, smashed his craft and threw him in the storming brine to swim to the shores of the island Skhería. Here, Zeus’s daughter, grey-eyed Athena, arranged for Nausikaa to bring the battered castaway to be respectfully received in the court of her father Alkínoös, where Ulysses relates his frustrated homeward journey. Here also he hears the blind rhapsode’s valorisation of his own Troy exploits – experience translated into symbolic fiction, an encounter with a fictional self (re-enacted in the Godard film as the white-suited Michel Picoli and the film’s puppet-like Ulysses actor pass to either side of the Malaparte villa’s rooftop wall, a wedge between film and reality) (Figure 1.10.10).

From Skhería, Ulysses is shipped homeward and, ‘put on Ithaka, with gifts untold of bronze and gold’. These Pallas Athena advises him to hide, then to enter Ithaka and even his own house in the guise of a beggar. Approaching his home, Ulysses passes Clearwater, a sensuous spring house (a water house):

where the people fill their jars.

Ithakos, Nêritos and Polyktos built it,

[island and mountain names – a topographical anchoring]

and round it on the humid ground a grove,

a circular wood of poplars grew. Ice cold

in runnels from a high rock ran the spring,

and over it there stood an altar stone

to cool the nymphs, where men going by laid offerings.10

He finds his own home overrun, commandeered by a crowd of suitors revelling in the ‘gracious timbered hall’, competing for abandoned Penelope’s hand, feasting daily on ‘his cattle, oxen and fat sheep, and drinking up rivers of wine’. The arrangement of the house unfolds as Ulysses and son Telémakhos gorily dispatch the interlopers on their own final journey:

The suitors’ ghosts are called away by Hermes . . . bearing the golden wand . . . He led them down dank ways . . . all squeaking as bats . . . all flitting criss-cross in the dark . . . over grey Ocean tides, the Snowy Rock, past shores of dream and narrows of the sunset, in swift flight to where the Dead inhabit wastes of asphodel at the world’s end.11

Ulysses’s house is arranged around ‘the pillared hall’, scene of the slaughter. Here Penelope sat, weaving by day, having promised to choose between suitors when the fabric was finished, unravelling by night (a potent metaphor for the trajectory of culture – a continual reweaving of the same material). At night, she withdraws to her high room (as does the Favorita in the Malaparte villa). Fragmentary details offer clues to the extent of Ulysses’s house, but not to its type or focus:

A distant storeroom where the master’s treasure lay . . .

. . . a women’s hall and inner rooms for 50 female slaves . . .

. . . the packed earth floor of the pillared hall – Athena watched, in the form of a swallow perched on a black beam in the smoky air under the roof . . .

. . . the courtyard of the beautiful house, a courtyard altar – the sanctuary of Zeus . . .

. . . outdoors, a court, under the gate, between the round house and the palisade.

Penelope instructs her maid to make up a bed for Ulysses ‘. . . and place it outside the bedchamber my lord built with his own hands’. This stings Ulysses to retort:

No mortal . . . could budge it with a crowbar.

There is our pact and pledge, our secret sign, built into that bed – my handiwork.

. . . An old trunk of olive

Grew like a pillar on the building plot,

And I laid out our bedroom round that tree,

Lined up the stone walls, built the walls and roof,

Gave it doorways and smooth fitting doors.

Then I . . .

hewed and shaped that stump . . . from roots up

into a bedpost, drilled it . . .

. . . and stretched a bed between – a pliant web

of oxhide thongs dyed crimson.12

Here, the DNA of the Mediterranean house is specified, an irrefutable anchoring, the ‘techne’ of making and dwelling, the goal of the journey, or, as Rudofsky argued, ‘homes should be a cultural refuge, the aesthetic backdrop for our passions’. After Odysseus’s 20-year Odyssey, horizon-scanning windows seem less than necessary, for there is no more a distant goal.

1 McDonough 1999.

2 Homer 1992, Book V, l. 166.

3 Ulysses’s previous stop before Kalypso’s island and where his crew sealed their fate by slaughtering the god Helios’s cattle.

4 Homer 1992, Book V, ll. 65–78.

5 Domus, March 1938, p. 123

6 Domus, 1937, no. 109, p. 265.

7 Rudofsky’s 1970 [1964] book (and MOMA exhibition), Architecture Without Architects.

8 Homer 1992, Book V, ll. 203–8.

9 Ibid., Book V, ll. 251–70.

10 Ibid., Book XVII, ll. 262–8.

11 Ibid., Book XXIV, ll. 1–15.

12 Ibid., Book XXII, ll. 214–27.