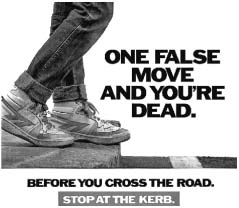

Figure 2.8.1 One False Move UK road-safety campaign, 1980s

Source: Department for Transport Archives

One False Move and You’re Dead! This alarmingly stark and simple message stands alongside a close-up of a teenager’s feet on the edge of a kerb, on the huge billboards of the 1980s government road-safety campaign poster (Figure 2.8.1). The clarity of the image is enhanced by the absence of any surrounding context – there are no buildings or other people or activity in the background. It is a message about everywhere and nowhere. It was part of an ambitious campaign to improve pedestrian safety by influencing walking patterns and removing children from the threat of traffic, reinforcing the notion of a strong conceptual boundary to separate the world of the pedestrian from the world of traffic. The penalties for transgressing this boundary were severe indeed!

Figure 2.8.1 One False Move UK road-safety campaign, 1980s

Source: Department for Transport Archives

The One False Move campaign represents one memorable manifestation of the principle of physical and psychological separation that dominated architecture, urban planning and traffic engineering for much of the twentieth century. The appearance of the motor vehicle in significant numbers during the 1920s prompted a fundamental re-evaluation of the relationship between movement and public space. Traditionally, streets and the spaces between buildings had served the simultaneous demands for both movement and the exchanges and human interactions that constitute civic life. For Le Corbusier and other delegates at the CIAM Congress of Athens of 1933, there was ‘no place for the street with its traffic’ in the modern city.1

Nowhere was the principle of segregation of traffic from civic life more clearly articulated and persuasively argued than in the 1963 Traffic in Towns, the report of the committee chaired by Colin Buchanan to advise government policy on urban planning and transport.2 The central conclusion of this influential study called for systematic segregation between pedestrian and vehicular worlds. The pedestrian precinct, overbridges and underpasses, barriers and physical separation emerge as essential components of urban form. It was a message strongly endorsed by government policy and professional institutions in many countries. ‘Segregation should be the keynote of modern road design’ was the first sentence of the UK government’s 1965 Roads in Urban Areas. It seemed a self-evident truth that the requirements for efficient and safe movement of traffic were fundamentally incompatible with the qualities of urban space. Notions of public space and pedestrian boundaries had to be redefined. Hence, the need for the safety campaign to restrain the movement of teenagers – One False Move and You’re Dead!

As we approach the second century of motorised movement, our understanding of the relationship between driver behaviour, traffic and the qualities of public space is changing rapidly. The publication in the UK of Manual for Streets 2 in 20103 and the emergence of shared space and integrated streets as design concepts have begun to establish a fundamentally contrasting paradigm for streets and urban spaces, in place of separation and segregation. This chapter looks at some of the theoretical and practical background to this change, and its implica -tions for the relationship between architecture, urban design and traffic engineering. It is a change that builds on a growing understanding of behavioural psychology and the influence of place and context on human interaction and movement, and especially the relationship between drivers and the complex, unpredictable and fragile world of pedestrian activity.

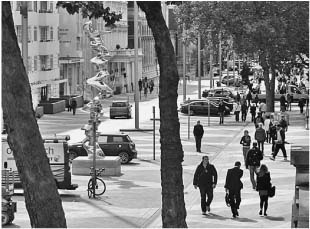

Drive a car into Exhibition Road in Kensington, West London, and you will find that, although you are still on the public highway, most characteristics of the familiar urban street have disappeared (Figures 2.8.2 and 2.8.3). Road markings, pedestrian crossings, traffic signals, signs and high kerbs have been replaced by a new layout and spatial arrangement. The diagonal paving pattern of the surface materials continues unbroken from building to building across the street. Boundaries between the carriageway and the pavement are more subtle, and street furniture, lighting and paving combine to create a single, unified space. For the driver, the experience can be slightly unnerving, especially where bicyclists and pedestrians are milling around and where the museums, Imperial College and the other great institutional buildings spill out into the space. As a driver, you have to concentrate and remain alert. Your speed drops, not because of the 20-mph speed limit, but because there is so much to take in. Conventional separation of the carriageway from urban life has vanished, leaving some ambiguity about priorities, ownership and permission.

Exhibition Road is unusual. Its recent transformation was the ambitious and expensive outcome of London’s leading politicians’ and the Mayor’s determination to create a street of appropriate cultural significance in this richly endowed corner of the capital. But Exhibition Road is not an isolated example. It represents a more widespread and growing realisation of a new paradigm for traffic in towns. It demonstrates an approach equally relevant for the design, management and maintenance of small, rural high streets and village centres, and reflects an attempt to minimise the adverse impacts of traffic on the economics, social fabric and quality of life, wherever movement and civic life are expected to coexist.

Figure 2.8.2 Exhibition Road, London: an experiment in combining traffic and pedestrians

Source: Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

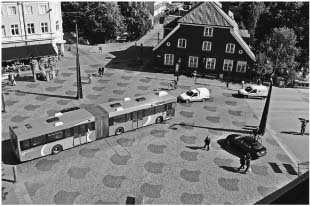

Figure 2.8.3 Exhibition Road, bus and milk float move slowly through a space also used by people

Source: Photograph by Ben Hamilton-Baillie

The widespread problems associated with traffic and the built and natural environment have been well documented. The Save Our Streets campaign of 20084 reflected the extent to which traffic impact dominates local concerns in almost every neighbourhood and community. Take a walk in almost any urban, suburban or rural settlement, and the immediate experience is dominated and framed, not by the architecture or landscape, but by the signs, signals, markings, bollards, barriers and linear asphalt of the traffic world. Pedestrian movement flows are constrained to limited peripheral space and occasional formal crossing points. As David Engwicht has pointed out in Mental Speed Bumps,5 drivers adopt speeds depending on the degree of psychological retreat of human activity from streets. This establishes a vicious circle, as people withdraw from trafficked space, generating higher speeds and further withdrawal. Reversing this cycle is critical to establishing a less damaging relationship between traffic and public space.

The need to re-evaluate the balance between traffic and urban quality reflects much more than concern for aesthetic sensibilities. There is an urgent economic imperative. With the dramatic changes in trading and retailing prompted by out-of-town superstores and the Internet, the purpose of many of our streets and public spaces has fundamentally changed. No longer necessary for the functional necessities of trade and distribution of goods and services, town centres have become places that only exist to fulfil higher-order expectations for human interaction and enjoyment. It is no longer possible for towns to exist solely as functional frames for market activity; they have to be able to attract human presence through intrinsic qualities. This change is prompting the search for new ways to reconcile traffic movement with the future purpose of urban space.

Development of new techniques and principles for integrating traffic movement into civic life owes much to pioneering work in Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden and especially the Netherlands, from the late 1970s onwards. Engineers such as Joost Váhl began to explore new models for residential streets, leading to the concept of the woonerf in places such as Delft, Gouda and Culemburg. In the north of the Netherlands, the late Hans Monderman introduced a remarkable palette of measures for streets and intersections in his position as head of road safety for his native Friesland. Starting with the aim of quieter village centres, Monderman developed a range of techniques that extended traffic engineering to encompass all aspects of landscape, history, geology and architecture. He sought to re-integrate the driver into the normal civilities of the pedestrian world, and, to his surprise, he found that the alterations he made appeared to improve both the safety and efficiency of traffic movement, even when applied to busier urban junctions and high streets.

At the core of Monderman’s alterations lie a number of principles that apply an under -standing of the influence of context and place to the experience of movement among drivers and pedestrians. He and his colleagues were unusual as traffic engineers in extending their understanding of the influences on traffic beyond the confines of the highway boundary, to encompass every detail of place, as well as the driver’s perceptions and expectations. They established principles that combined to reduce speeds, create greater driver awareness, inte -grate traffic movement and produce adaptable, efficient public space. Three principles are especially noteworthy.

The first concerns the design and presentation of transition points between the higher-speed ‘highway’ and the lower-speed public realm. Rather than placing road signs and nameboards without reference to the architecture, the intention is to create clear, distinctive gateways or entry points to neighbourhoods, towns or villages, through a combination of materials, land -scape, lighting and dimensions that reinforce perceptions of transition (Figure 2.8.4). Measures to highlight changes in scale and a shift from linear continuity towards spatial complexity often require the elimination of centre-lines and road markings, with an introduction of visual narrowing to announce the transition. The identification of transition points requires special attention to, and exploitation of, natural features, such as bridges, notable buildings or changes in the landscape, as these help influence driver awareness and decisions.

The second principle involves the application of place-making design to significant reference points along a street, especially to intersections and key junctions. Rather than placing signals, kerbs and highway furniture without reference to the context, the new traffic engineering and place-making draws on the distinctive characteristics and specific geometry of potential spatial landmarks. The elements of successful place-making are infinitely varied, but common characteristics include a focus on some central element (perhaps a statue, lamp or tree), or a simple frame in paving or lighting to define a space. It can be merely the careful positioning of lamps, street furniture or planting. Place-making techniques can contribute to the creation of clear transitions and are critical to creating legible sequences that, in the driver’s perception, reinforce the distinction between highways and public space.

Figure 2.8.4 Skvallertorget, a square in the Swedish town of Norrköping: the paving pattern reasserts the identity of the square as outdoor room

Source: Tyrens, Sweden

Figure 2.8.5 Drachten, Friesland, Netherlands: coexistence of cars, cyclists and pedestrians

Source: Photograph by Ben Hamilton-Baillie

The third principle involves the relationship between buildings, the activities they generate, and the design and configuration of the street. Establishing a conversation between the traffic environment and adjacent events appears to contribute to more responsive driver behaviour and to lower speeds. Thus, a street running past a church or a pub, a school or a park, a town hall or a theatre will exhibit subtle differences in alignment, materials or arrangement to form a visual and psychological connection between traffic space and context (Figure 2.8.5). This approach marks a notable shift in the analysis and representation of streets. Conventional highway-engineering drawings show streets with little or no reference to surrounding buildings, entrances or visual landmarks, often limited to the formal highway boundary. By contrast, projects such as Exhibition Road and New Road in Brighton have been conceived and drawn as an urban continuum. Building in small clues related to the context appears to improve the response of drivers to the complexity of urban situations, by breaking down the linear anonymity of featureless streets with a series of punctuation marks.

The potential for such an integrated approach to street design has implications for a wide range of typical urban spaces, junctions and street types. The disconnected, hostile experience of the ring road, observed by Stephen Walker (Chapter 2.6), could be reconnected to the city, while still serving its transport function. The transformation of the former ring road around Ashford in Kent of 2007 is one example. A former one-way, three-lane segregated highway has been returned to low-speed, two-way movement and redesigned to create a rich and varied sequence of places through which the high volume of traffic moves at lower, smoother speeds. Underpasses, signals, barriers, signage and road markings have been removed, and drivers find themselves negotiating their passage through a distinct and, at times, deliberately ambiguous series of boulevards and spaces. The street is no longer a road or highway, although it continues to fulfil its traffic function, with less congestion and fewer serious accidents than before. The monitoring of the first 3 years’ operation revealed a reduction in injuries of around 40 per cent.6

Many observers of this new approach to traffic movement and design speculate on how far the principles might be extended to busier streets and routes. To date, we have insufficient case studies to know the answer. However, there are encouraging signs that the principles of place-making and context-specific street design may help to tackle problems where heavy traffic tends to divide and isolate communities. Poynton, a small market town in Cheshire, is built around a crossroads on the busy route between Manchester and Stoke (Figures 2.8.6 and 2.8.7). Over 26,000 vehicles a day pass through Fountain Place, the name once given to the junction at the heart of the town, fronted by the post office, shops and magnificent church that define the centre. Over the years, extensive traffic signals, multiple approach lanes and highway clutter reduced Fountain Place to a hostile, congested highway intersection, with little human life or economic value. In 2012, the crossroads was reconfigured. Traffic signals were removed, carriageways were simplified, strong entry gateways were created, and a clear spatial identity returned to Fountain Place through new paving materials, planting and lighting. To date, the junction appears to cope more successfully with the volume of traffic and has reduced pedestrian delays. The reduced congestion and low-speed environment are allowing civic activity to return to the town centre.

The emerging understanding of this potentially improved relationship between traffic and the built environment has important implications for the relationship between architecture, urban design and traffic engineering. Conventionally, these have been separated into distinct and distant disciplines. Integrated streetscapes require much greater understanding among architects of the constraints, of vehicular tracking, movement patterns and the pedestrian interactions that determine the dynamics of traffic. Likewise, the world of traffic engineering could profit from an ability to exploit and adapt the potential of architecture and place-making to influence driver behaviour and integrate vehicular flows successfully into urban environments.

Our understanding of movement and its relationship to space is undergoing a profound revolution. Many of the assumptions underpinning the segregation of traffic from civic life are now being challenged by the evidence emerging from schemes such as Exhibition Road, Ashford and Poynton. Understanding the experience of movement and the influence of context opens an important new field of research and experimentation, one that holds the potential to address the adverse effects of the segregation of traffic from civic life. Low-speed design and close integration with the distinctive characteristics of place may help foster new patterns of urban life and vitality. Moving away from the mechanical, deterministic views of twentieth-century segregation allows a human-centred street-movement pattern to emerge. One false move, and you remain very much alive.

Figure 2.8.6 Fountain Place, Poynton, Cheshire, UK: replanning of the traffic route by Hamilton-Baillie Associates

Source: Photograph by Ben Hamilton-Baillie

Figure 2.8.7 Fountain Place, Poynton, Cheshire, UK: replanning of the traffic route by Hamilton-Baillie Associates

Source: Ben Hamilton-Baillie

1 Le Corbusier, The Athens Charter (1933) 1973.

2 HMSO 1963a.

3 Department for Transport (2010) Manual for Streets 2, CIHT.

4 English Heritage (2008) Save Our Streets.

5 Engwicht 2007.

6 Kent County Council (2011) Ashford three-year monitoring review. R. Bright (internal document).