Peter Blundell Jones, Jianghua Wang and Bing Jiang

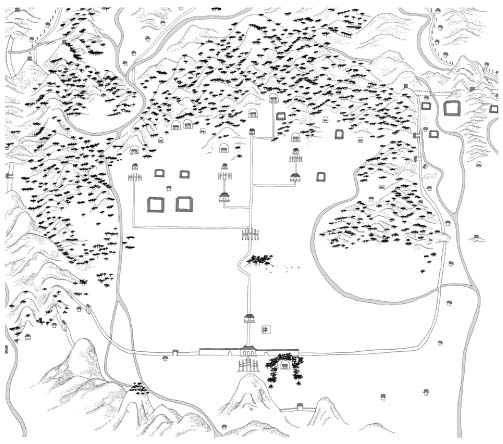

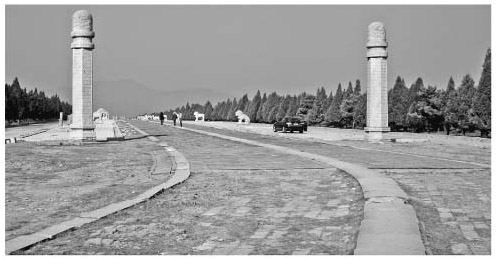

In traditional Chinese architecture, the making of routes and progressions for ritual purposes was especially elaborate, for the society was rigidly hierarchical and devoted to Confucian concepts of respect for parents and ancestors. In addition, the philosophy of Daoism engendered a great respect for the forces of nature and the way they were considered to manifest themselves in the landscape as flows of energy, qi.1 It is, therefore, hardly surprising that some of the most impressive spatial progressions in China are found at royal tombs. As the emperor, as Son of Heaven, was supposedly able to intercede with natural forces, these are also places where the landscape is most visibly engaged, and the practice of feng-shui is most carefully observed.2 The East Royal Tombs of the Qing Dynasty at Zunhua, Hebei Province, north east of Beijing, are relatively late, the earliest dating from 1661,3 but they follow the same general pattern as earlier tombs and have the advantage of being well preserved, and their relationship with the surrounding landscape is still relatively unspoiled. The enormous sacred precinct, of around 2,500 km2, includes five separate tombs for emperors and yet more for queens and concubines.4 Embedded side by side in a range of rising hills at the north end of the site, just in front of the remains of the (by then) long disused Great Wall,5 they are approached by a single sacred way nearly 10 km long, along which a sequence of monuments unfolds (see plans Figures 3.5.1 and 3.5.2 and photo sequence Figures 3.5.3 to 3.5.15). The modern visitor is free to wander, with little sense of the once forbidden and protected nature of the huge site.

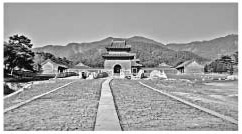

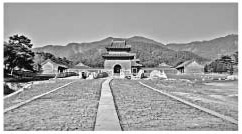

The starting point is a broad paifang or ceremonial gate (Figure 3.5.3), with five arches hierarchically heightened towards the centre, largely symbolic roofs carved with imitation tiles and elaborate applied decoration. It is no physical barrier, but it does mark the beginning and centre line of the route towards the tombs, leading north towards the main gate. In China, all ceremonial building complexes were laid out on a more or less south–north axis, including the Forbidden City, for the emperor was regarded as connected with the sun, and his throne had to face south. This resulted in axial progressions for all official architecture, but, unlike Western baroque layouts, the axis was not left open. It had to be closed to the south, often with a screen wall set opposite the entrance. So, south of the paifang, seen axially as one returns (see p. 156), is a lone pointed hill, a propitious gift in feng-shui terms, and the main reason for the choice of site.6

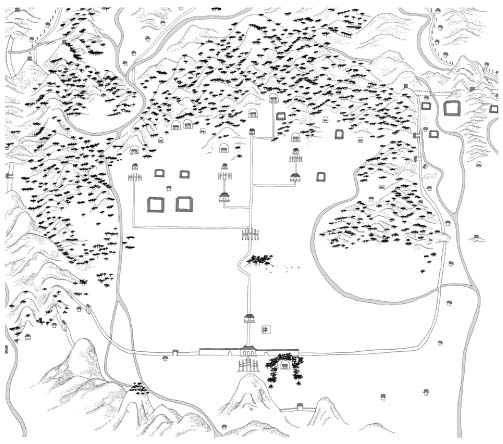

Figure 3.5.1 General plan of the eastern tomb complex, entered centre bottom and leading to several tombs set in the foot of the mountains at the top, showing the roads, monuments and outer wall; north is top (redrawn after a version in the Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo)

Walking north, one soon reaches the three-arched and roofed main gate in the boundary wall (Figure 3.5.4 and plan above). This was not fully the edge, for there were three notional boundary layers beyond it, designated with regular coloured stakes in red, white and blue, showing, respectively, the fire buffer zone, the 60-m limit of hunting, and the 5-km limit for fires and mining.7 This is typical of how, in parallel with its obsessive axiality, Chinese architecture stressed progressive enclosure. The main gate is a hip-roofed building,8 built in masonry rendered in royal red, but with doors studded with ceremonial ‘nails’ of royal number,9 and a tiled roof carrying on its hip ends the customary array of protective mythical beasts. The central arch was heightened for passage by the emperor, his route marked on the ground by a raised central path of smooth stone paving, along which he could walk or be carried.10 The gate afforded shelter to guards and a temporary rest for visitors, and just within was a changing pavilion, where honoured visitors could adopt more appropriate attire. The reigning emperor also changed dress between different parts of his ritual visit.

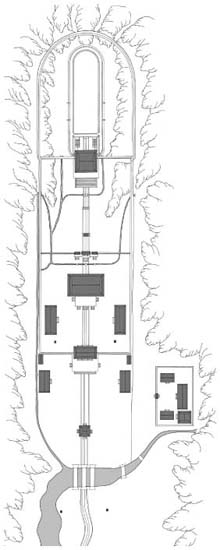

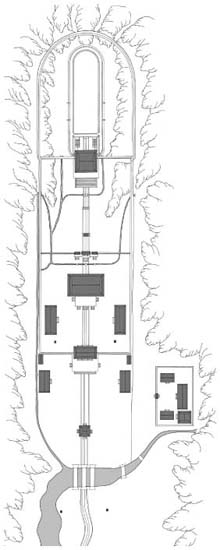

Figure 3.5.2 Detailed plan of the first tomb in the series, that of Emperor Shunzhi, from the triple bridge at the bottom through the sequence of courts to the tomb embedded in the hill at the top (redrawn after a version in Chinese archives).

Figure 3.5.3 First paifang, a purely ceremonial, freestanding gate set axially between the holy mountain and the main gate, which can just be seen through the central arch

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

Figure 3.5.4 Main gate set in the wall that enclosed the whole complex. The merit pavilion beyond can just be seen through the half-open middle gate

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

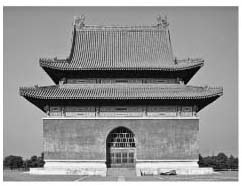

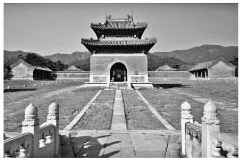

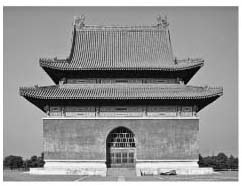

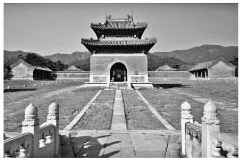

Figure 3.5.5 Merit pavilion, a square building containing a sculpture of a tortoise with a stele on its back recording the virtues of the emperor

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

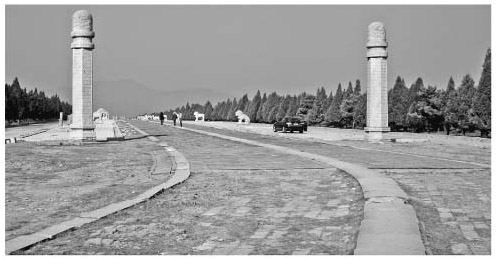

From the main gate, the next monument is visible on axis about 500 m away (Figure 3.5.5). It is a small square tower, with a double-eaved roof, hipped below, half gable above, doubly symmetrical, with an archway facing each cardinal direction, and standing at the centre of a larger square defined by four stone pylons. It has more protective animals on its ridge and corners and increased decoration of the upper wall. This is a so-called merit pavilion, containing in its raised ground floor the figure of a tortoise, a holy animal in Chinese mythology,11 with an inscribed stone stele erected on its back enumerating the merits of the first Qing emperor, Shunzhi. The tortoise’s head faces back towards the site entrance, its body blocking direct progression. Visitors circumvent it to regain the axis, and then proceed straight until another natural feature intervenes (Figure 3.5.1). This is a low hill lying between entrance and tomb, an earthly organ to be respected, and so the route veers westward to circumvent it, and then swings back on to axis (Figure 3.5.6), all the time broad, horizontal and centred on the emperor’s stripe of raised paving. Distant mountains become clearer, and a long, straight walk opens with paired stone pylons, followed by a sequence of stone figures on each side, first animals, then soldiers and courtiers, as if on parade. There are eighteen pairs, twice the imperial number nine.

Ten minutes’ walk brings one to an inner paifang (Figure 3.5.7), the dragon and phoenix gate. It is smaller and more delicate, with three arches this time, the middle again larger than the sides. The gateways are real, and one is obliged to pass through, for there are walls between and to the sides, but no closable doors and no roofs over the openings. Roofs instead sit on intermediate walls treated with the centralised tiling patterns normal for a screen wall.12 It serves as an intermediate gate, after which progress is less formal. The ground drops and curves left and right to cross a ceremonial bridge of seven arches, skewed away from the axis but almost in line. Water nurtures life and brings qi, and is also one of the five elements or phases in Daoism. The good feng-shui site has protective mountains to the north and is open to the south, and a river should pass in front.

Figure 3.5.6 (top) After the merit pavilion, the route curves to avoid a low hill, and then returns to the axis, now lined with a parade of sculpted figures

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

Figure 3.5.7 (bottom) The parade terminates at an inner paifang, another ceremonial gate. The mountain range in which the tombs are embedded can be seen behind

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

Departing from the bridge, the way runs on, contiguous in its paving with the emperor’s central reservation, but curving with the contours and dividing off at various junctions to approach later tombs. It crosses another bridge over a second small stream, this time with

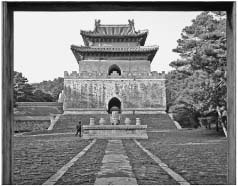

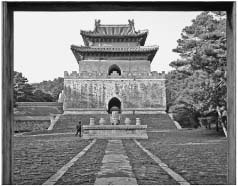

Figure 3.5.8 After meandering about and crossing more bridges, the route arrives at Emperor Shunzhi’s tomb, always with raised central path for the visiting living emperor

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

Figure 3.5.9 A triple bridge leads axially to a merit pavilion, again with tortoise and stele

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

Figure 3.5.10 Behind this, on axis, is the gate to the walled tomb precinct

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

Figure 3.5.11 Through the gate and on to the main hall, where most offerings are made

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

five arches. The axial route is reasserted on approach to the primary tomb of the site, that of Emperor Shunzhi (Figure 3.5.8). The elaborate walled complex has a sequence of courts, pavilions and halls and backs into the chosen burial hill (Figure 3.5.2). The mountains behind were symbolically interpreted for feng-shui when the location was selected, reportedly the choice of the emperor on a hunting trip. The approach crosses yet another small stream (Figure 3.5.10), this time via three parallel three-arched bridges. After the bridge comes an open forecourt leading to the gatehouse, but the axis is blocked by a second merit pavilion, again double eaved and housing another sculpted tortoise with a stele on its back. Next lies the main gate to the tomb complex (Figure 3.5.10), a five-bay hall with hipped roof and three wooden double doors set half-way across its plan to share shelter between inside and out. It has bracketing, painted decoration and nine rows of nine symbolic nails in each door. There are dragon-like creatures on the ridge ends and a full complement of protective animals on the hips.13 As high-roofed walls encircle the tomb, this is the only way in.

Figure 3.5.12 Directly behind the blind-backed main hall, the axis is re-presented with another triple set of gates, here seen from the side as one circumvents the hall to the east

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

Figure 3.5.13 Back on axis and passing through the gate, there is another paifang that frames this shot. In front of us is a stone carved table of offerings, then steps up to the arched tomb entrance. Above, reached from stairs beyond, is the last merit pavilion

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

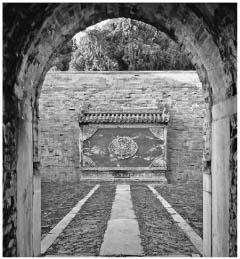

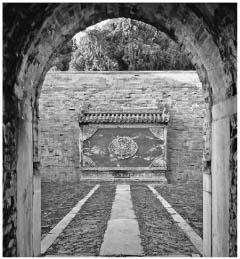

Figure 3.5.14 Passing through the tomb passage, one discovers a final court, with a screen wall signalling the tomb beyond

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

The gate opens to a large court. On either side stand censers for burning incense and side pavilions for preparation of offerings. On axis is the main hall, set on a platform of nine steps in three flights, the middle the emperor’s route paved with a dragon relief (Figure 3.5.11). This double-eaved, five-bay building was the principal site for offerings to the deceased emperor, and it visually blocks access to the tomb. One circumvents the blind-backed hall to rediscover the axis at three roofed gates, approached by separate flights of steps, nine in the middle and eight to the sides (Figure 3.5.12), and to reach them one again crosses a small stream, running east–west. The gates are set in a ceramic-lined wall, each with double wooden doors. They lead to an upper sloping court, where the centre line recurs in a small roofed paifang offering declarations of merit, and then a table of petrified offerings, for the vessels are carved in stone (Figure 3.5.13). A last water channel crosses east to west, curving in to traverse the centre at right angles and then curving out again. A sloping ramp, now without central path, leads steeply up to the single arched entrance and then tunnels through the solid stone base of the last ceremonial building, passing the concealed entrance to the tomb below. It re-emerges in a shallow court, where the emperor’s central paving re-appears briefly, only to plunge beneath a wall blocked by a small roofed screen wall, as if he might pass on through to the tomb (Figure 3.5.14). However, the real continuation is sideways, up ramps to right and left of the court, which lead to the final, double-eaved merit pavilion above the tunnel. From the front of its gallery, one can look back over the whole complex, but a path behind encircles the earth mound of the tomb (Figure 3.5.15), departing on one side to return on the other.

Figure 3.5.15 Hillside beyond the wall, showing the mound over the tomb, where the living emperor adds ceremonial earth to his ancestor’s grave

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

The Shunzhi Emperor’s entombment

Visiting the buildings and walking the spirit path arouse curiosity about how the death rites unfolded, and so it would be rewarding to match the architectural sequence to a single, fully known ritual sequence, ideally that of the emperor’s entombment. However, this is not easily achievable, partly for lack of information, partly because the process was unusually protracted. The Shunzhi Emperor died unexpectedly of smallpox, aged only 23, in 1661, with the tomb decided but not yet built, and so there was a 2-year delay before his interment. After customary mourning of 15 days in Beijing, he was taken with great ceremony to nearby Jingshang to lie in state.14 Following Manchu custom, he was then cremated 100 days after his death, his urn remaining in Jingshang.15 Only in the summer of 1663 was it moved to the tomb, and records reveal more about the enormous, week-long public procession from the capital than they do about the entombment. The spirit way was still incomplete, for the main mourning hall was only finished a year or so later, but the paucity of information is also due to the entombment having been a relatively restricted process, carried out by officers of princely rank and unwitnessed by outsiders.16 What we do know is that the procession arrived and waited in the last of the five overnight camps provided along the way, where a tent-like hall housed the revered remains within a rope outer wall with guarded gates. The urn and tablet were retained there for some weeks, offerings being made daily, until the propitious date for transfer to the tomb, calculated by royal mathematicians, arrived. Three days earlier, sacrifices were made to the ancestors, the spirits of Heaven, Earth, the planets, mountains and rivers. The guard of honour was reconstituted, and the high-ranking officers waited outside the doors of the tent, lower-ranking ones waiting outside the gates of the rope fence. Officers of the Rites Department made offerings, while the seals, books and urns of the emperor and his two queens buried with him were transferred to carriages, and the procession set off for the tomb. When they reached the inner gate, behind the yet uncompleted hall, the highest-ranking officers stood inside and the lower-ranking ones outside, and, at a precisely calculated hour, the urns were put into the tomb, and the tomb was sealed. An officer made an offering of three cups of wine before the closed door, and the effigies and mourning bands used in the processions were ceremonially burned. Next day, the officers returned to offer more wine as a farewell.17

Regular memorial visits

The interment ritual was but the starting point in the life of a tomb, for the rituals of remembrance continued as if the emperor were still present. His spirit was offered meals three times every day, set out with due ceremony and later cleared away, and, twice a month, at no moon and full moon, came more elaborate observances in celebration of the lunar calendar.18 Yet more elaborate offerings were made at the eight annual festivals and on the birth and death days of the deceased emperor. On days that marked seasonal changes, such as tomb-sweeping day in the spring, either the reigning emperor himself or his representative had to be present, while the meals offered to the ancestor included eighteen main dishes and fifty-six desserts. All this required a considerable staff, and a special yamen, or court office, was set up to look after the tombs, which of course grew in number as the dynasty progressed. By the late nineteenth century, each tomb had assigned to it 130 servants of the Imperial Household, 110 soldiers as guards, 120 officers and assistants of the Rites Department and 40 workmen from the Department of Works: in all, 400 persons. All lived in their own camps nearby, the Imperial Household camp within the sacred precinct. In addition, the army kept a force of 3,500 soldiers outside to police the perimeter.19

The climactic ritual occasion was the visit of the reigning emperor, which occurred about once a year and involved a 5-day processional march from Beijing, accompanied by other members of the royal family, distinguished officers of state and an enormous retinue, staying overnight in temporary palaces erected for the purpose. Having arrived along the spirit path, the emperor’s duty was to visit all the imperial tombs in turn, to make offerings and ritual kowtows to his ancestors. In deference to his fathers, he entered the tomb complexes via the east gate, rather than through the hierarchically dominant central one that was normally his prerogative.20 His offerings to his fathers and mothers were made, not just in the outer court, at the main hall, where the daily offerings were made, but also in the inner court, in front of the tomb entrance. The tomb remained sealed, but, in an almost private gesture of special deference to his ancestor, the emperor would, as a final rite, ascend the upper mound above the tomb and there distribute some fresh earth, taking care not to disturb his sleeping father beneath.

The type and sequences of these ceremonies were well established, and their meanings were understood, controlled by the Department of Rites. They were part of a spatial and symbolic system that applied to all official buildings and even to houses. The latter focused on the ancestral hall, the holy centre as defined by Confucianism, which taught a duty of utmost respect for the father and reinforced the continuity of the paternal line.21 The emperor was effectively the father of the entire society, and so the royal tomb, in its space and symbolism, represented the extreme case of ancestral celebration, justifying all the rest. The demigod emperor could not simply disappear. When he died, in theory, his soul split, one half returning to Heaven, the other half remaining with his body, which had to be returned to the Earth. The influence of ancestors survives even today among ordinary Chinese, who welcome their return during the New Year festival and make offerings to them.22 One need acknowledge no belief in the supernatural to see the value of such shared remembrance: the daily and monthly offerings at the tombs of the Chinese emperors and the annual visit of the emperor himself to kowtow to his father, grandfather and others provided some guarantee of their continuing influence. More essentially, it showed the continuity of the family line and its achievements.

The modern tourist is allowed almost everywhere, and tourism has become the raison d’être of ‘world heritage sites’. However, in imperial times, few were permitted even to enter the precinct. As a public spectacle, the annual journey of the emperor from the capital was all that ordinary people witnessed, the tomb site being as ‘forbidden’ as the imperial city. The more privileged you were, the further you could enter, penetrating more deeply into the nesting series of enclosures, through gates and across bridges, towards the sacred heart, which was always clear in Chinese buildings. It might contain the family’s sacred ancestral tablets, the seat of a magistrate, images of the Buddha or even the body, dead or living, of the emperor himself, implying a universal reading of spatial hierarchy. Official institutions were set out on a south–north axis, the central path always reserved for the emperor, his representative or the patriarch. The symbolic treatment of doors, gates and roofs along the way followed a consistent vocabulary regulated by the Department of Rites. Consistency of spatial layout and types of ritual progression across dynasties for hundreds and even thousands of years suggest that these meanings were well established and effective. The tomb and its spirit way were, therefore, not mere memorials, but part of a more universal system of architectural representation. In a society where the emperor was Son of Heaven and the souls of past emperors were a guarantee of continuity, their place of rest was a sacred place, and its architecture was an exemplary model, even if few ever saw it.

Notes