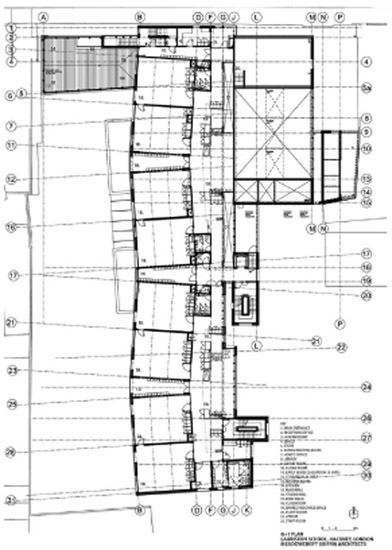

Figure 3.7.1 (left) Lauriston School classroom wing plan: street at top, with main entrance and hall to right

The primary school is a formative experience, socially and emotionally, as well as educationally. As a child’s first main setting outside the home, it acts as a transitional environment, an intermediary in preparing the child for the adult world. Therefore, the range of spaces offered and the movement between them supports the associated spectrum of developing experiences, from dynamic engagement and negotiation with the whole school community, to quiet spaces for focused learning and more personal contemplation and recovery.

Lauriston School is in Hackney, in north-east London, and started off as a Victorian board school, but it was rebuilt in the 1970s as a single-storey, modernist building. The Victorian buildings were used as educational-authority storage before being sold off for conversion into apartments in the 1990s. Both school buildings had been models of innovation in their time, for the board school had pioneered a newly invented learning environment at the start of general education, and its 1970s replacement had proposed open-plan learning, with all classrooms as three-sided alcoves, opening off a connecting ring corridor. This promoted a shared sense of endeavour and allowed dynamic expression of each child’s work, but it had become cramped, as demands outstripped provision. One reason was more personalised learning, which increasingly requires smaller, cellular spaces, not anticipated in the 1970s model, owing to an increase in individual, one-to-one teaching. There were also increases in small-group work and pupils in need of extra support, such as reading recovery. Class sizes had increased from eighteen to twenty-two pupils in the 1970s to a threshold of thirty, and further additional space was required for the pupils with disabilities, including specialist support spaces, such as hygiene and health rooms, along with sensory rooms for withdrawal and recovery.1

To double its size and create more pupil places for the growing community, the school needed to be rebuilt. For the new Lauriston, completed in 2010, the staff and governors set a clear vision intended to capture the best of the previous schools’ qualities – their ‘Lauriston-ness’ – while relieving them from the struggle against inadequate space, poor-quality fabric, woeful lack of acoustic control, dismal environmental conditions, with classrooms that overheated in summer and were too cold in winter, and an excessively internalised space, with limited connections to street and city. Despite these problems, the teaching at Lauriston was recognised nationally as outstanding. The staff had developed multiple approaches to learning, engaging pupils through creative project work, often with artist collaboration. They had exploited and benefitted from the open-plan layout to create non-hierarchical links between pupils of all ages, and between the teaching and non-teaching staff:

At Lauriston we see ourselves as a community of learners. Fundamental to our philosophy is the belief that we are all learning all of the time. Learning is not something that happens in a linear way but something that is accessed in different ways at different times. We want the school to be a centre for learning that meets the needs of its community – a school fit for the 21st century and a centre of excellence for the creative and performing arts.2

The words of one young pupil encapsulated both the ethos and the physical condition that we first encountered: ‘Lauriston is one big classroom’.3 The challenge was to create a new building that matched the quality and innovation of the teaching. We (myself and Philip Meadowcroft) won the commission as the only practice that had not designed a new school before, on the basis that we understood this core desire to define and retain the ‘Lauriston-ness’, and that we would achieve its translation into the new, larger school in close collaboration with the whole school community.

Together with the school, we developed a dual focus for participation: micro, which explored specific briefing and design issues to ensure that the project was a learning resource for the school, and macro, to develop the rich memory of the site and to promote understanding of the process of change. During the first year of work with the school, we carried out a series of transformation workshops to investigate the history of the site. This allowed children and staff to engage with the rebuilding in a positive manner. Specific workshops were dedicated to each of the historic layers: the rural condition as watercress fields was invoked through a cress-growing project in science week; the product was eaten in a summer-term picnic; and, in the autumn term, the playground was converted into a farm for a day. Later, the site had been developed as terraced housing, and so, in the winter term, a den was built in the playground to recall that setting, with role-play in Victorian costumes. As John Slyce, the school chair of governors, recalls:

During the various presentations, it became immediately clear to all of us on the panel that there was one practice that connected intimately with Lauriston’s ethos as it had evolved and developed – as often against as in agreement with the constraints and conditions of the building, or buildings, it grew out of. Ann Griffin and her team convinced us that they not only understood what we were putting forward as a somewhat complex brief – to preserve the school’s good practice that had emerged from less than ideal, if not a bad, and increasingly failing context – in a new school building that would double its size and intake on a constrained and live site. We also wanted to increase the available play and outdoor teaching spaces.4

Our initial involvement as architects was intensive. With a tight programme set by the target date for the first year of entry, there was no time for prolonged debate. Instead, we approached briefing and design in parallel, as an intensive, full-immersion process. The school invited us in, with complete access for observation and continual enquiry, so that we could understand how Lauriston could operate so well, while hamstrung by such physical limitations. I lived a day-to-day life there for the first 6 weeks, feeding back to the office sketches and proposals based on my findings, observing and talking to everyone in the school community.

These findings and the initial sketch proposals that grew from them were offered to the school quickly, as part of a developing dialogue. Frequent workshop sessions with staff, pupils and parents allowed reassessment of key aspects, alongside more structured reviews to ensure a formal sign-off process that matched the fast pace of design development. Two key observations revealed competing conditions in the existing school. First, movement through such a small building was a dynamic experience. Every surface was covered with display, and, with no space dedicated to pure circulation, class activity and individual support tuition spilled out into the corridor. This was partly expediency, every nook being brought into service owing to lack of space, and partly owing to the way the creative project work tended to focus around sinks in the corridor. Acting as a communicating device, the corridor of the 1970s school had engendered a sense of belonging and created these non-hierarchical links. It produced ‘a tangible atmosphere that is alive, in a school where we create the future through learning together’.5 Our second key observation was that, despite the school’s ideals of inclusion and open access, its dynamic learning environment was cut off from the local community. Owing to its location as an island block in the middle of the site, there was no easy street connection to extend the school’s use to the wider community, nor did the school have a visible presence on the street.

To reconnect the new Lauriston with the community, we radically reorganised the building’s massing, reasserting its civic identity and controlling the transition from city scale to the individual classroom. On the northern boundary of the site, facing the original Victorian school, the new school steps forward to meet the street. It knits together the gap in the terrace of housing with a new community frontage that invites access, and it elevates the main classrooms above ground, as a linear bridge structure running into the depth of the site, which minimises the footprint to free up outside space for playgrounds.

Throughout the school, movement was developed as a sequence of street-like forms to create shared territories, where people come together (Figure 3.7.1). Spaces for movement are converted from solely pragmatic circulation into social and creative spaces, usable for teaching and learning, but also promoting a shared dynamic of curiosity and excitement. Movement becomes a process of communication. The first of these internal streets is the main-entrance art foyer, reconnecting the city/community with the school. Paved in the same slabs as outside, it celebrates the school’s ethos as a centre of excellence for the arts, with displays of work lining the walls and suspended from a three-storey light-well that links all teaching levels. The street expands to form a courtyard space for the library. It connects directly into the two halls and provides more protective alcove entrances for the ground-level teaching spaces, devoted to the youngest children. At the south end, the street opens into the playgrounds, bringing views of greenery and outside play into the school’s heart.

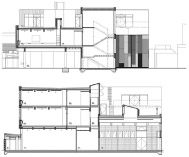

The placing of stairs was fundamental to the redefinition of space from mere circulation into space for learning and being (Figures 3.7.2 and 3.7.7). The raised, linear treehouse block has three stairs: one to the north, one to the south and one on the centre line, each serving a cluster of four classrooms and so removed from through traffic. Such dedicated vertical access allowed the creation at first-floor level of another internal street, a dynamic shared space linking the classrooms within each cluster. This was intended to create a sense of identity and security for each young child within the larger school. By relieving the connecting areas from their core circulation role, these spaces co-opt corridors into studio- or laboratory-like spaces, to promote free or structured learning in various degrees and to offer shared visibility for every child’s work. Equally important is the inflection of the four classrooms within each cluster, which are formed as two pairs, each angled in plan to close down the corridor width at the outside edges of the cluster, and then to belly out as a more generous expansion of the shared space in the centre (Figure 3.7.3). This redistributes floor area effectively from what would otherwise be a continuous corridor into a precisely configured and spatially contained set of spaces for shared activities. Large sinks encourage shared creative exploration that invites work of all scales, resolving the restriction of the previous school’s small butler sinks, a fault identified by Cornelia Parker: when working with the pupils on a project, she had noted that the scale of the work produced was limited by the scale of the sinks.6

Figure 3.7.1 (left) Lauriston School classroom wing plan: street at top, with main entrance and hall to right

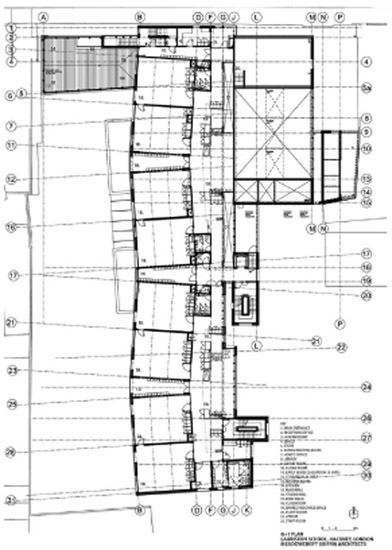

Figure 3.7.2 (right) Sections through staircase, and through hall and classroom wing Source: Drawings by Ann Griffin with Meadowcroft Griffin

What sustains the success of these dynamic, street-like parts of the school is the range of smaller spaces that offer choice and control for each individual, whether child or adult, to move away from the central focus to various degrees. A number of smaller cellular rooms are distributed about the school, easily accessible from each cluster and each with a different view and orientation. These can be used for structured small groups or individual support, functions lacking in the previous school. Now, reading-recovery sessions have a bespoke space

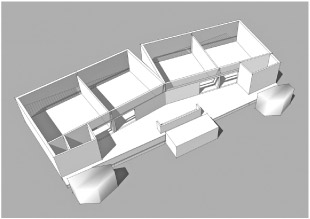

Figure 3.7.3 Group of four classrooms, with the shared space between them and central sink area

Source: Computer projection by Ann Griffin with Meadowcroft Griffin

Figure 3.7.4 The sink area as the central point of the classroom group

Source: Photograph by Tim Soar

– ‘the best room in the building’7 – the projected, first-floor glazed corner of the treehouse block, hovering over the entrance, with views to the articulated brickwork of the Victorian school opposite. Less enclosed and defined alcoves offer layers of separation, so that a child can retreat momentarily to a quiet reading corner on the fringes of the main, shared resource space, to be apart yet still within the group, observing until they feel ready to participate. This sense of choice fosters the young child’s developing sense of self and awareness as an individual, as well as being part of the school community.

As our designs developed further, we expanded the school participation workshops to try out key elements of the new building, including the shared resource spaces. In the hall, the only large communal space in the existing school, we regularly set up one-to-one mock-ups for staff and pupils of different ages to test proposals. We invited comments about appropriate size, movement flow, ease of use, spatial definition and the likelihood of engagement versus distraction. The range of insights so gained helped us explore more closely which solutions would best fit the new school, both in terms of forecasting immediate use and in considering flexibility for future transformation to support new needs and changes in teaching approaches. Our initial proposals for the big sinks in the shared resource areas was to locate them more as islands in the widest section of the corridors, with shoulder-height storage as a screen to separate off a more defined circulation zone. The pupils were quick to point out that the screen would simply encourage passing children to jump up to look over. The three-dimensional movement mock-up prompted the more successful solution of removing the screen and reclaiming the circulation zone, creating a larger, more open activity area, and this was the version adopted (Figure 3.7.4). This key development transformed the experience and character of the shared spaces: instead of the bespoke sink and activity elements sitting as an island in the middle of the space, they became the space itself, defining its character and its spatial and emotional experience.

The use of the shared spaces was developed together with the school, setting a central wet area at the widest point between two smaller dry spaces for quieter activities: one a reading area with sofas and the year-group library, the other a role-play den, set up as an empty alcove lined with full-height grey pin board. This was likened to a large cardboard box, inviting endless recreation, and, when I visit, I enjoy seeing the evolving variety of interpretations, from spaceship, to forest, to World War Two bomb shelter.

The flexible, creative learning environment of the new Lauriston has proved highly successful: the clusters provide smaller-scale learning bases within the larger school. They stimulate dynamic communication between all year groups, inspiring curiosity, engagement, shared work and ease of communication, but they allow acoustic separation and containment of any learning space when required. Each classroom has a high-performance acoustic enclosure to ensure that louder groups in the shared resource space do not impinge on quieter, more focused activities, and vice versa. Even so, the doors are mostly left open, to allow and encourage flows of activity between the classroom proper and the shared areas. The classroom screens are fully glazed and were sized to recreate the same expanse of visual connection between the classroom and the shared activity areas as provided by the open-plan alcoves in the 1970s school. Generous areas of glazing and open doors allow views through the classrooms and cloakrooms, creating fluid boundaries between the learning spaces and inviting children to explore and engage in different ways (Figures 3.7.4 and 3.7.5).

A child’s understanding of the extent of their world might be thought of as equivalent to the length of view on offer.8 Looking out of the raised learning areas transforms the children’s

sense of connection to their world, lifting them out from the relatively insular, ground-hugging condition experienced in the previous school. Each classroom has a full-height window, dropping to the floor with a sense of vertigo that dares children to approach the edge of the space to gaze out to the city and the world beyond. We believe that choice and transition through the learning spaces in the new Lauriston are not just programmatic or pragmatic matters, but meet emotional needs. An individual child’s potential can be extended through more focused tasks, while an agitated child is allowed retreat and calm for readjustment, before rejoining the busy group. If boundaries between classrooms and shared activity spaces are fluid, they are nonetheless defined. The decision to allow the children free movement through the school invites them to move independently in and out of different learning spaces, and to engage in the diverse, child-scaled infrastructure of studio-like settings that promote learning together.

1 John Slyce, the school chair of governors:

We addressed how an educational ethos developed in a failing building might provide the guide. The stakeholders identified the aim to retain what they referred to as ‘Lauriston-ness’, or the particular meld of school ethos that gave rise to the style of teaching given the premises they were working in where the children were clearly thriving.

2 Heather Rockhold, Lauriston head teacher, from the original school brief, 2007.

3 Pupil’s comment on their experience of the existing 1970s Lauriston, from the original school brief, 2007.

4 John Slyce, oral communication with the architects.

5 Lauriston governors, from the original school brief, 2007.

6 Cornelia Parker, during her collaboration with Lauriston pupils through the Creative Partnerships project, 2006.

7 Reading-recovery teacher, 2010.

8 David Grandorge, school parent, during early consultation, 2007.