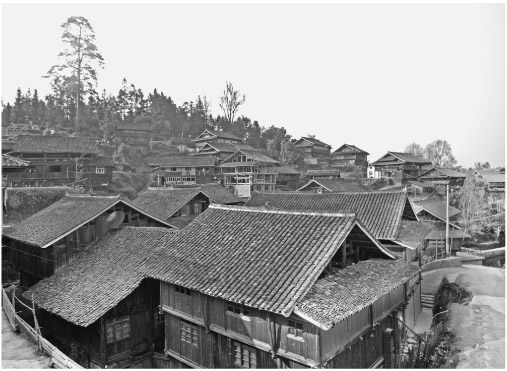

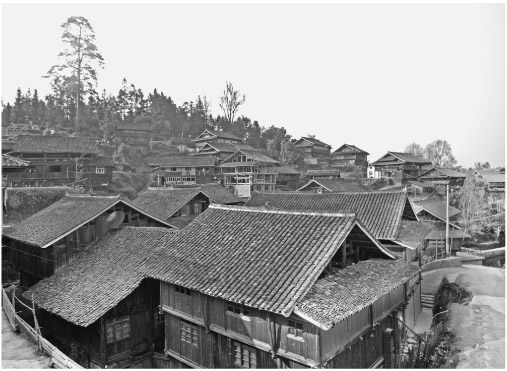

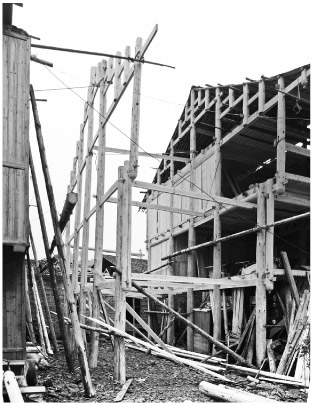

Figure 4.1.1 Dong dwellings at Ji Tang village, in Lingping County, Gouzhou province, China Source: Photograph by Derong Kong

Figure 4.1.1 Dong dwellings at Ji Tang village, in Lingping County, Gouzhou province, China Source: Photograph by Derong Kong

The Dong people are a minority group living in South West China, in a mountainous area shared between the provinces of Guizhou, Hunan and Guangxi. Until about 50 years ago, contact with the outside world was severely limited, and they were mainly left to their own devices. As they had no script, it was an oral culture, with much transmission by song. Their building followed a local carpentry tradition that is still prevalent, involving community participation and a series of rituals to mark the progress of a house.

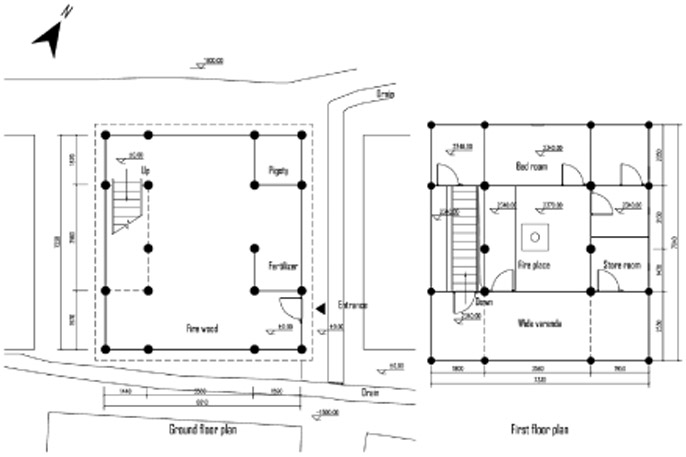

Figure 4.1.2 Typical Southern Dong house plan. Pan Jiliang’s house built in 1950s at Xiao Huang village, in Congjiang county, Guizhou province

Source: Drawing by Derong Kong

Construction of a new house usually happens after October, because then the harvest is finished, people have free time, and there is enough money and food available. The host’s relatives and friends should offer their help freely to the host, and refusal to cooperate is resented, for it is an accepted custom to help each other in daily life, and a mutual obligation is always implied. The building process involves the following roles: host, relative, friend, geomantic master, hand ink master, carpenter, mason. The core man is the host, and the construction process locates everyone’s position in the system, assigning a particular job, responsibility and obligation. The host is the subject who will dwell, physical space is constructed by the hand ink master and carpenter, and spirit connections are imported by the geomantic master. From beginning to end, the host is constantly involved, and so he has a close connection with his house and deep experience of its evolution.

The construction process that people join in is impressive, rational and complete: it is easy to remember. Through the ritual process, the meaning and significance of the house are shared and understood, and group participation holds together the small community. Each time the members build a new house, they repeat what the last generation has done, and their memory records events that have happened before. The constructed object helps maintain rules and principles, and construction events are compared, each event becoming a reference for following generations.

In our conversations, hand ink master Lu Wenli listed the general procedure of building a house.2 This is also the live project in a Dong carpenter’s education. Carpenters and apprentices at different levels of skill are involved, being assigned jobs at different stages of construction.

First, the site must be chosen. It could be the host’s old site or one bought for the purpose, but, if a fire has occurred there in the last 3 years, a special rite has to be performed before it can be used for building. The host invites a geomantic master to check the orientation and local topography. Taking into account the host’s date of birth, the geomantic master can calculate whether it will bring good or bad luck to the host, and what the best days are for starting the construction and, later, for erecting the structure.

Next comes the cleaning up of the site, making it flat. If the site has a difficult topography, its treatment can be arranged by mutual discussion. The host has to hire masons to sort out the site, and there can be a ritual for laying the stone bank.

The host must invite the geomantic master again to decide the direction of the house. Using a compass, he checks the form of the mountain that the house will be facing. Different hills imply different fortunes. This also involves reference to the hand ink master’s design. Now the design process can begin.

Taking into account the particular site conditions, the hand ink master discusses with the host the function, arrangement, size and structure of the house, and whether the site is big enough to allow three bays, and what size each bay could be. They also decide the depth of the house, the distance between columns, the structure of the roof and how many floors the host wants. Then, the plan of the ground floor is settled. The hand ink master has a coordinating system to help him remember the structure. The columns at ground floor are the starting point for the coordinate system. The whole structural system is based on personal construction experience, and so direct experience is the principle to organise and edit the code system. The important thing is that the system be convenient to remember and manage. He can use components as references to mark further components that fit with them. Figure 4.1.3 is an example of a carpenter’s code.

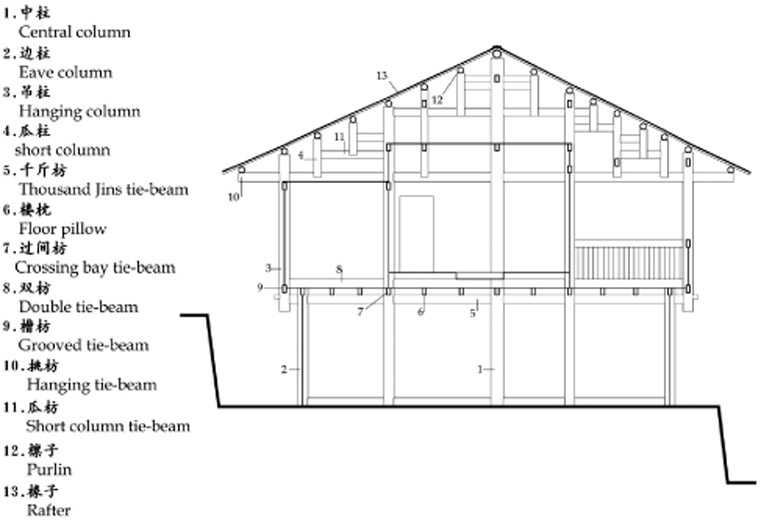

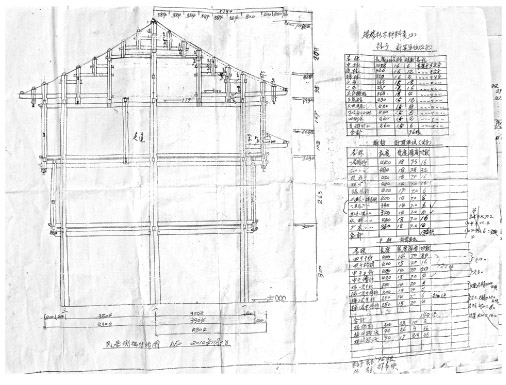

The hand ink master next thinks about the vertical assembly and roof structure. At this point, he can figure out the order of a flat frame, called Shan, ?, or fan, which embodies the key section (Figure 4.1.4). Then he can design tie-beams to connect these frames together and so complete the house structure. A model, or one simple drawing, may be used to explain the design. The hand ink master will also draw the dimensions of components on a Zhang pole, a kind of large ruler, to record the whole design (Figure 4.1.5).

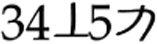

Figure 4.1.3 This means the third row, fourth column, fifth tie-beam

Figure 4.1.4 (facing page, top) Typical section of southern Dong house, showing so-called fan of structure. Pan Jiliang’s house built in 1950s at Xiao Huang village, in Congjiang county, Guizhou province

Source: Drawing by Derong Kong

Figure 4.1.5 (facing page, bottom) Master Lu Wenli’s Zhang pole set against a beam to mark it, 2010

Source: Photograph by Derong Kong

Figure 4.1.6 Drawing of hand ink master Lu Wenli’s new house, with a list of components at the side, 2010

Source: Drawing by Derong Kong

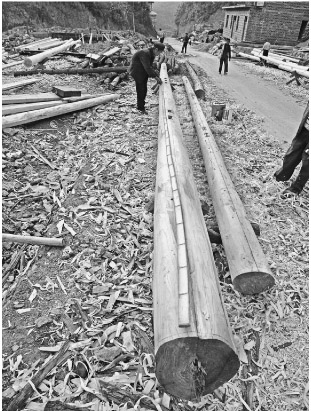

The hand ink master counts the exact number of components and then makes a list of timber and tiles for the project. The host must prepare the material: depending on what property he has, he can take the wood from his own hills or buy it from others. When the site is ready, the hand ink master goes to the site and uses thread, wooden sticks and the Zhang pole to establish the positions of the columns.

The first central column is the starting point, and the host chooses an auspicious day to cut the tree. Before they start, the hand ink master has to make an offering to the mountain god for permission, and then they can go ahead, but within strict rules. The woodcutter must be properly dressed, the first three cuts must be clean and sharp, and the tree must fall towards the top of the hill, with a pre-placed support to keep it off the ground. If these rules are respected and all goes well, they can continue the work; otherwise, they have to stop felling and choose another day to start it again. After the first tree is cut down, they use a local kind of fork to lift it and carry it back to the village, and on their way they must not shake the fork.3 More important is that no one should step on or over the cut tree. Then they can collect the rest of the timber, and carpenters are hired to process it into the rough sizes needed for the components. These trees have to be stacked for at least 3 months to dry off, so that there will not be too much warping when the structure is assembled.

After the materials are prepared, the hand ink master performs ceremonies called ‘inviting the wooden horse’ and ‘drawing the first ink line’, and then the preparation of the components begins. The first job is to make columns and to cut the mortises into them. Small bamboo sticks are used to measure the size of the hole, and the corresponding code is written for the tie-beam. Then, if other carpenters make the tie-beams, they can produce exactly the right size of tenon, and the tenon and mortise will fit. The hand ink master draws the ink line and then lets the apprentice reprocess it to finish the work.

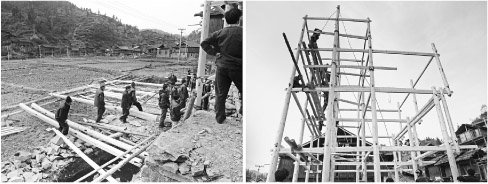

After all the components have been premade, the hand ink master asks the host to erect a scaffold for installing the house structure. The order of assembly is from bottom to top, and from inside to outside. The hand ink master preassembles the flat frame or fan of house structure, called Pai Shan,排扇.

Figure 4.1.7 Carpenters draw ink line and process the component, 2010 Source: Photograph by Derong Kong

Figure 4.1.8 Pre-assembling and erecting a house structure at Xiao Huang village, 2010, in Congjiang county, Guizhou province

Source: Photograph by Derong Kong

The central beam on the top of the central column is called the ‘treasure beam’. Before erecting the main structure, every component is premade, except for this treasure beam. It must be temporally ‘stolen’ from others, and cannot be prepared in advance. Tradition dictates that this is required for auspiciousness, as timber borrowed from the other’s hill to become the ridge for the house has the implicit meaning of ‘bringing treasure and blessing’. Stealing the ridge beam is carried out at midnight on the day before the main structure is erected. Four young men set off, one of them carrying a Luban axe,4 one bringing a small bag. The tree and the way to it have already been decided. After reciting some auspicious words, they cut down the tree and also take parts from the top to show that they bring it whole. Fastening a red cloth around the middle of the trunk, they carry it back to the village. Before leaving the site, they must put a red envelope with money equal to the value of the tree on the stump and then light firecrackers around the stump. When the owner of the tree hears the sound, he knows some people are stealing the ridge beam, and so he does not rush to accost them, but lets them take it. After the people have left, he goes to the stump to collect the money and pretends he is angry, scolding them for fun.5

An offering is made by opening a hole in the middle of the ridge beam, putting in some rice, tea, cinnabar and money, and then using part of the original wood to seal the hole. Next, the bamboo pen used by the hand ink master, two bricks of ink, one brush pen, a Chinese calendar, a copper coin and a wisp of coloured thread are set out over the hole, using a piece of red cloth 1 Chi long (1 Chi = 1/3 metre) and 2 Cuns (1 Cun = 1/3 decimetre or 3.33 centimetres) wide to wrap these things. The four corners of the red cloth are separately nailed into the beam with copper coins, which is called ‘wrapping the beam’. While the hand ink master wraps it, he recites auspicious words. Outside the red wrapping, he places a pair of chopsticks obtained from a successful merchant to pray for an auspicious future. He fastens the chopsticks to the ridge beam with red string.

The geomantic master calculates the correct time to erect the house structure. Before this is done, the hand ink master must perform a ritual called ‘dispel evil spirits’, to remind people to pay attention to safety and to obtain a feeling of security. After this, they can erect the main structure, connecting adjacent fans of the structural group with tie-beams. Then, they install the short columns and the short-column tie-beams to construct the roof structure, from bottom to top, and from outside to inside.

The geomantic master chooses a propitious day and time, and then the hand ink master performs the ritual for raising the treasure beam to the top of the central columns. A square table with offerings is placed on the site, and there must be a pair of new shoes for the hand ink master to wear when he climbs the structure to install the beam. With all in place, and with the beam on a wooden horse in front of the table, the hand ink master performs the ceremony of ‘fête the beam’.6 Then, a rope is attached to each end of the beam, and the hand ink master sings auspicious words. He kills a cockerell, spreading its blood on the beam. Then, two people standing at the top on each side slowly draw up the ridge beam, and firecrackers are let off as a vision of good fortune.7 When the beam has been placed on the tie-beam and the firecrackers have finished, the hand ink master puts on his new shoes and says auspicious words. Then, he climbs the structure, chanting some auspicious words. After he completes the installation of the beam, he throws prepared candy, glutinous rice cake and red envelopes to the crowds. People try to catch these things in a happy atmosphere.

Figure 4.1.9 Erecting structure and the half-finished house, at Xiao Huang village, 2010, in Congjiang county, Guizhou province

Source: Photograph by Derong Kong

On the day the beam is raised, all the relatives, friends and villagers who come to congratulate and help are given two feasts. One is before the raising of the beam, at noon, and is a normal meal. Later, following the raising, comes the main feast, including all the above people and others who come to celebrate.8 The site of the feast is usually the host’s old house, or a neighbour’s house near the new house. People sing an ‘erecting house drinking song’, and the hand ink master, carpenters and singing master take the main seats as honoured guests. The singing master sings a drinking song to praise the hand ink master’s technique. Then, the singing master sings to the host to offer his congratulations. In return, the host sings to the hand ink master and the singing master to express thanks.

Once the main structure is finished, the hand ink master checks the whole structure. The household will ask a mason to install the stone base of the columns. From bottom to top, carpenters install floor, wall, purlins, nailed-on rafters and tiles. Then, they decorate the fireplace room and one or two bedrooms and install the front door. The family can move into the new house, living in an uncompleted house while the rest of the construction is slowly finished. After completion, according to the owner’s requirements, there can be a ceremony to set up the front gate. The door is an important junction of inside and outside, private space and social space, etc.; it divides and connects the spaces of private and social life, allowing passage through from certain space to uncertain space. Its vital position determines its important meaning to the Dong people’s lives and is accompanied by many implications.

The door-frame is covered with red cloth, and two door hammers are fixed to the lintel of the door. The door hammers are carved with flowers, decorative linear ornaments or inscribed with two Chinese words, 三王, on the left and right. Left is ‘three’, here repre -senting Heaven; right is ‘king’, here representing Earth. They write symbols of heaven and earth to pray for a blessing. The top of the door is wider than the bottom, after the saying ‘wide sky, narrow earth’, so that treasure can easily fall from the sky. The wooden tie-beam for the threshold must be stolen in the same way as the treasure beam.

The threshold is regarded as ‘the dragon of the gate’;9 it is the tutelary deity of this wooden house. In order to prevent the ‘dragon of the gate’ from escaping, the middle of the threshold has hammered into it an iron nail, because people believe an iron nail can force the ‘dragon of the gate’ to stay, but they cannot use a copper nail, because, in legend, the dragon is not afraid of fire from sky or earth, only of a copper nail hammered into its waist.

There is also a ceremony for the front gate. The time to perform it is determined by the ghost master. The hand ink master presides and performs the ceremony. The hand ink master must dress in clean clothing to show respect. Pregnant women are forbidden to watch, because local people call a pregnant woman a ‘person with four eyes’, but the baby in her body is not complete, especially the baby’s eyes, which are not really opened. If the baby has a sight of you or an event, it might cause some danger and harm.

A table is placed beyond the door, and on the table are put some offerings. Door panels are put on both sides of the gate, covered with red cloth. After everything is arranged, the hand ink master stands in front of the table and burns incense and paper money. Then, he spreads water and recites words to clean the site, dispel the evil spirits and drive away dirty matter. After this ritual, people set off the crackers and set up the door panels. Then, the ceremony is completed.

When a family moves into a new house, they hold the ceremonies of ‘opening the wealth door’ and ‘lighting the fire to enter the house’; these express a good hope for prosperity. For the ceremony of ‘opening the wealth door’, the host must find a middle-aged man who has good luck, and who also has a son and daughter, to perform as Wealth Star. The carpenter who built the front door plays the mythical carpenter Lu Ban. People stand around them in several tiers to see their performance. When Wealth Star enters the house, the householder approaches him with a smiling face, and Wealth Star speedily extracts from his long bag money wrapped with red paper, which he gives to the householder, the so-called ‘gaining wealth’. Master Lu Ban kills a cock and spreads the blood on the door, representing a red, happy event. The money offered means red luck for 12 months. After the host takes it, he respectfully invites Wealth Star and master Lu Ban to sit on the chairs prepared in the central room.10 The host offers them tea and cigarettes. Then this ceremony is ended, but another follows.

The next ceremony, a literal house warming, is ‘Introducing the fire into the room’. First, the host must put cooking pots in the fireplace room and place a bundle of firewood in the fireplace. Hot coals are brought from the fireplace of the old house in a fire bowl. After Wealth Star and master Lu Ban have had a rest, the host invites them to light the fire. Wealth Star walks to the side of the fireplace and kneels down, blowing up the fire in the fire bowl to make a flame, and then he lights the firewood and puts it into the fireplace. As the fire flares up, Wealth Star sings a song in praise of this moment.

Then, Lu Ban solemnly takes out wooden shavings cut from the main beam, which have been carefully preserved, and puts them into the fireplace. As the fire ignites, everybody, including master Lu Ban and Wealth Star, cheers. Then, they set up iron trivets to support the pot over the flame to cook dishes and make a banquet. Master Lu Ban, Wealth Star, relatives and family members take seats at the table and drink ‘rich and honour wine’ together. So, we see the whole ritual process carried through from the first acts of construction to first dwelling in the finished house.11 Folk dwelling is an integral part of Dong traditional culture, its material form and a carrier for its inheritance and dissemination. The construction and use of a house are key links in this process, and the local carpenter plays a pivotal role.

1 Derong Kong, current PhD student at the University of Sheffield, from field research in 2010: ‘The Dong oral architecture: Among Dong people in China’.

2 One of my main informants during fieldwork at Xiao Huang village, in Congjiang county, Guizhou province, China, in October 2010.

3 It is a farm tool, like a garden fork with the prongs angled backwards so that it can be used for dragging. Local people call it an iron harrow, Tie pa, 铁耙 it is a widespread farm tool in China, used to dig up soil and clear vegetation.

4 A ceremonial axe remembering the mythical carpenter Lu Ban, supposed author of the Chinese carpenter’s manual Lu Ban Jing: see Ruitenbeek 1989.

5 Fu 1997, p. 182 (not available in English).

6 Ibid., p. 185.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid., p. 189.

9 Ibid., p. 191.

10 Ibid., p. 192.

11 Ibid., p. 193.