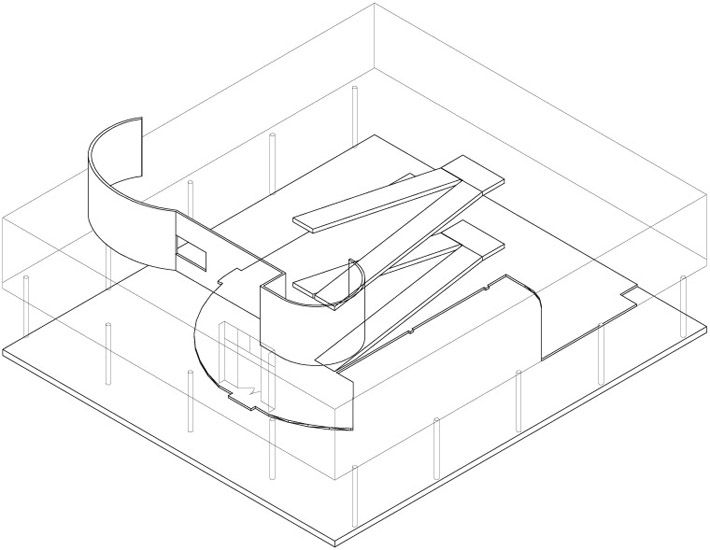

Figure 1.5.1 Diagram of the promenade in the Villa Savoye

Source: © Flora Samuel and Steve Coombs

The ‘promenade architecturale’ is a key term in the language of modern architecture. It appears for the first time in Le Corbusier’s description of the Villa Savoye at Poissy as built (1929–31), where it supersedes the term ‘circulation’, so often used in his early work.1 ‘In this house occurs a veritable promenade architecturale, offering aspects constantly varied, unexpected and sometimes astonishing’.2 Taken at a basic level, the promenade refers, of course, to the experience of walking through a building. Taken at a deeper level, like most things Corbusian, it refers to the complex web of ideas that underpin his work, most notably his interest in the relationship between individual subjectivity and collective values.

‘You enter: the architectural spectacle at once offers itself to the eye. You follow an itinerary and the perspectives develop with great variety, developing a play of light on the walls or making pools of shadow’, the purpose of all this being to help us ‘learn at the end of the day to appreciate what is available’.3 This statement deserves comparison with one by René Guilleré, a contemporary of Le Corbusier’s, who wrote, with regard to jazz, ‘In our new perspective there are not steps, no promenades. A man enters his environment – the environment is seen through the man. Both function through each other’.4 A key issue in the discussion of the promenade is for whom it was designed. What are the implications of designing a route to be perceived one way, when we will all perceive it so differently? This is a problem for the historian who, in describing one experience of the journey, gives expression to only one version.

Rather than giving my own interpretation of the promenade at the Villa Savoye, a journey that has been interpreted ad nauseam (Figure 1.5.1) – under the building, up the ramp, out into the garden and up to a window on the landscape – I shall focus instead on whom it was aimed at, clearly not the client alone. To do this, I shall refer to the depiction of the building in Le Corbusier’s carefully curated Oeuvre Complète, as well as the film Architecture d’aujourd’hui by Pierre Chenal (1930), in which Le Corbusier played an instrumental role. It is notable that neither follows a slavish route; they jump about offering a variety of different viewpoints; whether the promenade was one route or several within the same building remains debatable.

At the same time, I shall consider the promenade as a means to order information, and Le Corbusier loved order. The art historian David Joselit writes that the promenade is radical in being a very early example of a ‘format’, a ‘dynamic mechanism for aggregating content’, the World Wide Web being another example. He argues that, ‘what matters most is not the production of new content but its retrieval in intelligible patterns through acts of reframing, capturing, reiterating, and documenting’. The promenade enables the visitor to make new and individual sense of the information presented by the building. In this way, it anticipates the contemporary art of today, for example Sherry Levine’s Postcards #4 (2000), in that it is not about the objects being seen – which, in the age of mechanical reproduction, are of course endless – it is about the multiplicity of possible ways to see that object.5

Le Corbusier recognised that the building’s meaning is, for each person, in some sense individual. In his writing, he liked to toy with the point of view, leaping from first to third person singular – used to suggest an artificial degree of professional distance – and back again. At the same time, he was intensely aware of narrative stance, of the viewpoint of the individual vis-à-vis the viewpoint of the collective, an awareness that would play an important role in the development of the promenade. Le Corbusier wanted to make frameworks in which people could live out their own lives, while dictating very strongly exactly what that framework should be. It is one of those paradoxes that make his work so very interesting, so expressive of one of the central conundrums of architectural practice: how do you design buildings that allow others to be themselves?

As Andrew Ballantyne writes, ‘what gives buildings longevity is not what they meant for their designers, but what they come to mean for others’.6 Any discussion of the promenade needs to be prefaced by a consideration of its audience. Le Corbusier’s buildings were incomplete without people.7 They acted as a frame for the human life within. Without this, the promenade does not exist – it is the person that makes it whole, makes it happen. Hence the fact that the photos of the Villa Savoye included in the Oeuvre Complète are taken at eye level, or appear to be. In Le Corbusier’s depiction of the Villa Cook, a mannequin poignantly suggests human inhabitation, creating illusionistic games of scale against its verdant backdrop. In the Oeuvre Complète depiction of the Villa Savoye, items of clothing and equipment – a hat, a set of golf clubs, a pipe – talk of inhabitants unseen.8

When planning a film to be made about the Unité in Marseille, the building itself played an active role in the drama. Built matter was very much alive, working on people at two levels, the first bodily – the idea, Platonic in origin,9 being that affecting the emotions would affect how people think – the second intellectually, ‘for those with eyes to see’.10

Le Corbusier took a great interest in Orphism, which alluded, simultaneously, to an ancient mystery cult and a contemporary art movement instigated by the poet Guillaume Apollinaire.11 Orphism was at the root of multiple world religions, meaning that its symbolism had wide applicability. One dualism at the heart of Orphic religion was the relationship between light and dark, in other words spirit and matter, which impacted on Le Corbusier’s architecture in multiple ways. A clear example is his preoccupation with Jacob’s ladder, the route from earth to heaven.12 The connection between this biblical ladder and the promenade is made clear in the case of the Maison Guiette in Antwerp (1926), where he describes the stair that serves the various floors as being like, ‘the ladder of Jacob which Charlie Chaplin climbs in The Kid’ (1921).13 It is my belief that Le Corbusier’s promenades are plays upon this original topos. In my book Le Corbusier and the Architectural Promenade, I argue that the Villa Savoye is the exemplification of the Jacob’s ladder route.14 Indeed, Le Corbusier wrote, in the Oeuvre Complète, that it is necessary here ‘to go and find the sun’ in the solarium, which ‘crowning the ensemble’, is ‘a very rich architectural element’.15 This then is the focus of the promenade, which begins in the muted spaces of the entrance and finishes in a blaze of light. Finding the sun, the central message of Le Corbusier’s inner world, is thus central to the narrative of the promenade.

Given that the promenade was designed for a multiplicity of different viewpoints, how should we refer to the person who enters the experience? I find myself choosing the word ‘reader’, as it suggests an active role in the interpretation of the building. I take my cue from Guiliana Bruno, who writes of the way in which the architecture can be ‘“read” as it is traversed’.16 Further, ‘As we go through it, it goes though us.’ Reader is the word also used by film-maker Sergei Eisenstein, much admired by Le Corbusier, whose theory of montage occupies the interstices of this account.17 Le Corbusier stated, ‘architecture and film are the only two arts of our time’, before going on to note that, ‘in my own work I seem to think as Eisenstein does in his films’.18 Bruno describes his thinking as, ‘pivotal in an attempt to trace the theoretical interplay of film, architecture, and travel practices’.19

Le Corbusier’s audience is ‘the spectator’ and, ultimately, ‘the human eye’, completely disembodied, floating around the building at a specified height. The eye, for Le Corbusier, is restless and challenging. ‘[It] can reach a considerable distance and, like a clear lens, sees everything even beyond what was intended or wished.’20 David Joselit writes, ‘The architectural promenade gives form to a continuous modulation of vision through movement: a now rising, now curving platform along which to proceed.’ Kenneth Frampton evocatively describes this effect as, ‘a topographic itinerary in which the floor planes bend upward to form ramps and stairs . . . fused with the walls so as to create the illusion of “walking up the walls”’.21

The axonometric projection is often used by Le Corbusier to define the elements of a route. As Yve-Alain Bois points out, ‘there is no central point in axonometry; it is entirely based on the notion of permutability, of infinite transformations’.22 In the early drawings, arrows are used by Le Corbusier to indicate designated routes within his buildings, but he stopped using them around 1930; however, Le Corbusier never stopped imagining himself into the spaces of his plans – rough process drawings often reveal traces of fine lines drawn repeatedly, as Le Corbusier’s pencil point went round and round the plan, acting out the motions of daily life.23 These, coupled with the countless rough perspectival sketches that exist of individual events en route within his buildings, indicate the full extent of his preoccupation with lived space and, hence, his interest in film.

Pierre Chenal’s movie Architecture d’aujourd’hui (1930) was presented originally with subtitles by Le Corbusier and a soundtrack provided by his brother Albert Jeanneret. It begins with a locating shot of the façade from the ground-level garden, moving up and along the ribbon windows that open on to the living room and the first-floor hanging garden beyond. Referring to the way the eye can pan across the view, Frampton writes of the ‘cinematic effect’ of this window type from the inside.24 Here, it is used in reverse. The view provides a clue as to where the camera will be positioned next, another garden space, the hanging garden itself, where it tilts and pans along and up the ramp to the rooftop solarium, in this way following the promenade from ground to roof. The shot feels full of potential, waiting for human contact to make sense of these abstract forms and spaces. Next, the camera is positioned at rooftop level, looking down on a woman as she comes through the door into the hanging garden and starts walking briskly up the ramp, her face in full view. Then, with a trick of continuity, the woman is seen walking up the same portion of ramp – this time from within the stairwell from which we have just seen her emerge, as though reliving her experience from that angle. With further editorial sleight of hand, the camera then returns to the ramp to catch the woman’s back as she strides up to the solarium window, the fulcrum of the entire house. The emphasis of the shot is on her hand moving along the delightfully curved handrail, which occupies the middle of the frame.

The woman, now being filmed from rooftop level, is seen taking a chair and moving it into a position, hidden from us by plants, from which she can appreciate the view from the solarium. She settles down to enjoy the ultimate experience that the house has to offer. Then, in an echo of the very first, locating, shot, the camera is positioned back down in the garden, looking at the solarium window from below. From here, it is moved further back into the woods, but it still looks at the same window, a reminder of the viewpoint of the woman, who sits in comfort, unseen behind the frame. Technical constraints are likely to have limited Chenal in the amount of shots that he used. Despite this, the screen geography of the space is extremely clear. The camera angles suggest a sequence of sunny spaces, each leading on from one to other, which are stitched together by the movements of the body. It is impossible, in film, to show a person progressing up a house in one shot; continuity techniques are needed to make sense of the sequences and the changing position of the camera. It is the absence and then presence of the person that make it far more poignant.

Le Corbusier was acutely aware of the multiple subjectivities that might play a part in completing the building. Multiple viewpoints were, after all, central to the creation of the purist canvas, where bottles, jugs and so on can be seen from below, above and in elevation simultaneously. His bêtes noires were the buildings of the baroque, whose undemocratic, perspectival games were designed to be seen from one fixed point, that of king or bishop. Just as postmodern theory gave credence to all viewpoints, no matter how low in status, Le Corbusier’s buildings resist a hierarchy of viewpoint, something that works in counterpoint to the crescendo of light and drama that constitutes his Jacob’s ladder-type promenades.

The promenades in his buildings are available to all, whether the rich industrialist or the radiant farmer, but, in the end, the delights of architectural detail as art – spatial games and hidden meanings – are the territory of the rarified few who enter into the club of architecture. I believe, as did Le Corbusier, that buildings can be read in a variety of different ways, depending upon who is doing the reading. We should try to create architecture that allows the readings of others into the fold. Although he might have used all sorts of abstract, didactic, rigid and formal techniques in the evolution of his ideas, techniques that largely deny the fluidity of human existence, he did at least recognise the needs of what he called ‘the individual and the binomial’. Returning to Joselit, ‘Le Corbusier’s topography (and its diagrammatic or permuta tional legacy among contemporary architects) incorporates a concept – and a physical experience – of centrifugal vision, of what Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari might call “lines of flight”.’25 Perhaps ironically for one who has been portrayed as the arch exponent of modernism and the totalising narratives of truth, Le Corbusier was revolutionary in his deep understanding of viewpoint and its variation from person to person, as encapsulated in the promenade.

1 ‘Circulation’ is particularly prevalent in Precisions, where a section of a chapter is devoted to the subject (Le Corbusier 1991, pp. 128–33). This was originally published as Précisions sur un état présent de l’architecture et de l’urbanisme (Le Corbusier 1930).

2 Le Corbusier and Jeanneret 1946, p. 24.

3 Le Corbusier and Jeanneret 1995a, p. 60; originally published in 1937. Translation from Benton 1987, p. 4.

4 René Guilleré, quoted in ‘The synchronisation of the senses’ in Eisenstein 1977, p. 81; first published 1943.

5 Joselit 2003, p. 48.

6 Andrew Ballantyne, ‘Living the romantic landscape (after Deleuze and Guattari)’, in Arnold and Sofaer 2008, p. 30.

7 Le Corbusier and Jeanneret 1943, pp. 134–5; originally published in 1937.

8 Le Corbusier and Jeanneret 1995b, p. 26; originally published in 1935.

9 Plato, The Republic III, in Buchanan 1997, p. 389.

10 Le Corbusier 1987, p. 169; originally published in French in 1925.

11 Flora Samuel, Orphism in the Work of Le Corbusier, unpublished PhD thesis, Cardiff University, 2000.

12 See Le Corbusier 1989, p. 8; originally published in 1950.

13 Le Corbusier 1995a, p. 136; originally published in 1937. There are various edited versions of this film, but the 1971 Chaplin-edited version does not contain an image of Jacob’s ladder. There is, however, an extraordinary dream sequence in which Chaplin’s alter ego, the tramp, dreams of his slum home translated to heaven, bedecked in flowers, in which all the people whom he knows have sprouted wings, including the dog. The dialectical nature of these two worlds is then broken down. It is no wonder that Le Corbusier admired Chaplin so much – including him within the images in the Electronic Poem – he played with so many of the issues that Le Corbusier held dear.

14 Samuel 2010.

15 Le Corbusier 1995a, p. 187.

16 Bruno 2007, p. 58.

17 Sergei Eisenstein, ‘Montage of attractions’, in Eisenstein 1977, pp. 181–3 (181). See François Penz, ‘Architecture and the screen from photography to synthetic imaging’, in Thomas and Penz 2003, p. 146, for a discussion of the close links between modernist architecture and film.

18 This interview is cited in Cohen 1992, p. 49.

19 Bruno 2007, p. 57.

20 Le Corbusier 1960, p. 175.

21 Frampton 2001, p.79.

22 For Yve-Alain Bois, it ‘functions, in part, to make possible a cinematic reading’, in Sergei M. Eisenstein, Yve-Alain Bois and Michael Glenny (1989) Montage and architecture, Assemblage, no. 10, pp. 110–31 (p. 114).

23 See, for example, FLC 29310 in Allen Brooks, Archive, Volume XVII, p. 462.

24 Frampton 1996, p. 144. ‘I see reflections on the water, I see beautiful boats sail past, I see the Alps, framed as in a museum, panel by panel’, wrote Le Corbusier of his own beleaguered entry for the League of Nations competition (Le Corbusier 1991, p. 48).

25 Joselit 2003, p. 48.