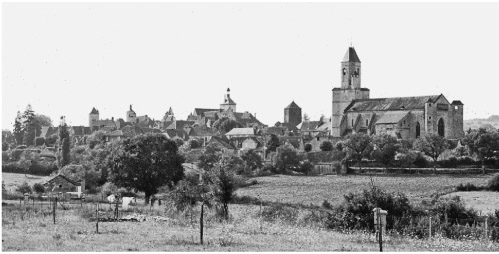

Figure 00.1 The whole town of Martel, Lot, France, as seen from the south east in 1972

Architecture and the experience of movement

Figure 00.1 The whole town of Martel, Lot, France, as seen from the south east in 1972

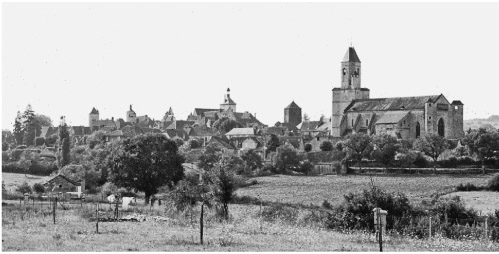

Figure 00.2 Street in the centre of Martel, next to the Hotel de Ville

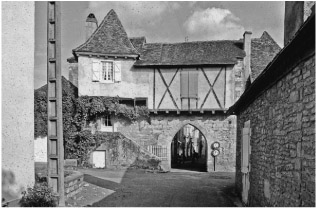

Figure 00.3 One of the surviving gates, west side

Source: All three photographs by Peter Blundell Jones

The chief distinction of the little town of Martel in the Lot, France (Figures 00.1–00.3), is that, having been an important medieval centre, it saw centuries of relative neglect, so that its population by the mid twentieth century was smaller than it had been in the sixteenth.1 Therefore, the town has remained visible as an entity, with old roads leading to original gates, a central marketplace and chateau, tower houses that marked the skyline for prosperous merchants, and a huge church to welcome pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostela. You can buy postcards of the church and chateau, but the place is best appreciated on foot as an unfolding sequence of experience, in which transition from country to suburb to major and then minor streets is accompanied by progress across thresholds and through layers of fabric, major buildings playing an appropriately dominant role against a background of ordinary ones.

Many, if not most, towns were like this before the twentieth century, and their perceived aesthetic merit was often recorded by artists from nearby hills, the towered skyline a matter of local pride. Their organic ordering went largely unrecognised, until Camillo Sitte began to theorise about it in the 1880s, just at the moment when town planning was starting up as a discipline. Simple though his theories were, they depended on the idea of the experience of movement, of how one was drawn to walk down a street by a landmark or by how the square at the end unfolded as an outdoor room (Figures 00.4 and 00.5). Although some of his followers used his principles in new work to great effect,2 the very title of Sitte’s book, Town Planning on Artistic Principles, led to it being relegated under the banner of the aesthetic, and that is more or less where it has remained.3

Meanwhile, cities grew remorselessly, methods of transport changed, and movement, both in cities and within buildings, became dominated by the mechanical disciplines of ‘circulation’, necessary to link the zoned functions famously declared in the Charter of Athens.4 On the street, motor vehicles took over, and traffic planning became the main priority, with one-way streets and ring roads making it necessary to head north to go south, or east to go west, in a counterintuitive way, so that, at the end of the twentieth century, satellite navigation arrived only just in time to save drivers from total confusion. Outside the city, crossing the country no longer meant moving from town to town, because most towns and villages were bypassed, and motorways followed direct routes despite the topography, so that the inherent logic and long tradition of what Le Corbusier had dismissed as ‘the donkey path’ was lost. In consequence, the landscape was deprived of its old coherence and experienced in an entirely new way.

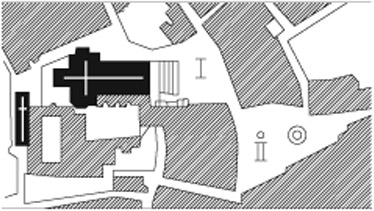

Figure 00.4 Plan of the centre of San Gimignano, as presented by Sitte in his book Town Planning of Artistic Principles

Figure 00.5 Typical sketch from Sitte’s book, showing the effect of a tower in Bern

At a smaller scale, experience within buildings changed in a parallel manner. As they grew bigger and more complicated, they were entered by labyrinths of blind corridors, and, as lifts anaesthetised all sense of vertical progression, way-finding became entirely a matter of signs and numbers, or, in desperate cases, of following painted lines on the floor or wall. It now seems ironic that these changes took place against a background of talk from leading architects, more explicit than ever before, about the experience of movement: talk about the excitement of four dimensions, about architectural promenades, about the thrills of flowing space. By contrast, precious little is recorded about the experience of movement in Vitruvius and his Renaissance followers, and yet concerns about sequence and progression are evident in many, if not most, buildings from antiquity and the Renaissance, and also in the so-called vernacular, and so perhaps the lack of discussion is not so much because it was ignored, as because it was taken for granted.

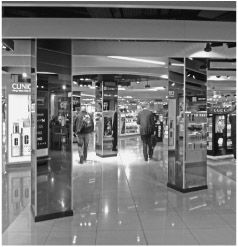

Some of the worst experiences of movement in modern life occur at airports – surprisingly, in view of the priority necessarily given to circulation. This is perhaps because the considerable logistical problems tend to be dealt with in an entirely mechanical way, which fails to overcome the need to traverse considerable distances on foot. A particularly grim example is the long underground travelator linking terminals at Frankfurt (Figure 00.6), which offers circulation pure and simple, as if the rest of life has been put on hold. At the other end of the scale is the airport shopping mall, now designed to confuse: a deliberate labyrinth, breaking the rules of efficient circulation to trap anxious passengers hurrying towards their planes and to persuade them to part with their money (Figure 00.7). No wonder Jacques Tati took the airport as the main target for his satire on mechanised life, Playtime, or that Marc Augé has seen airports as the very epitome of the non-place.5

Figure 00.6 Frankfurt airport, the underground travellator

Figure 00.7 Manchester Airport, sales labyrinth

Whether one enjoys the promenade of the street, walking for pleasure in parks and gardens, or the ascent of the ramp in Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, the experience of movement through architecture and through the larger urban or natural landscape has too often been treated as an ‘aesthetic’ extra, which is perhaps why we put up so meekly with circulation pure and simple. Too often, the aesthetic is seen as opposed to the useful or purposeful, and yet life is not so easily subdivisible. It is vital to our well-being that we know where we are and where we are going, in both an immediate, literal sense and in a longer-term, metaphorical sense. How these two are connected, this book will gradually reveal.

This book is divided into four parts, to produce a shifting perspective for the reader. The first, revolving around what Le Corbusier called the ‘promenade architecturale’ (see Chapter 1.6), looks at movement through space as it has been conventionally discussed and interpreted by architects, planners and landscape architects. We offer a relatively short and highly selective survey of this potentially vast subject, with entries chosen for their variety and sensitivity. They reveal a long-standing concern for route and organisation, for progressions in space that are legible, enjoyable, memorable, and above all that make sense. Through their contrasts of place and period, these texts also reveal how much unfolding architectural spaces have to do with changing social habits and assumptions. But the designer as author is seldom dictator, and the inhabitants may not share his or her interpretation, or behave as expected. Besides, ordering and intentions may not be consistent, for the fabric of the city can be created by many anonymous hands, and so-called natural landscapes remain without an author. We ‘read’ all such places nonetheless, for, as with texts, paintings, music, films and other works of art, the environment always has a reader, whose role it is actively to construct an interpretation in finding his or her way, even when none was intended.

The second part of this book therefore concerns this process of ‘reading’, and how this is bound up with walking or with other ways of traversing the territory. Critical theory has occasionally gone so far as to dismiss the author altogether, setting the entire responsibility with the reader, and the French Situationists, with their dérives, proved the point by walking routes wholly unintended by planners and unrelated to the inherited hierarchy of the city (see Chapter 2.3), finding unlikely byways and shortcuts, new experiences with new meanings. In this sense, the city is not so much ‘designed’ as ‘discovered’, and constantly rediscovered in different forms as read by the visitor or inhabitant. And movement does not have to be pedestrian, for, if reading of route first takes place on foot, it continues in different forms in the train, the car, the plane. These modern experiences of transition have become increasingly prominent, and walking, once taken for granted, has in many environments become more difficult and even impossible, so that making sense of places on foot as the original or primary experience can be said to have deteriorated. It is hardly surprising, then, that walking has simultaneously become something of a cult and has even been declared an art.6 Although this is helpful in drawing new attention to the experience, it could also add to its perceived distance from everyday life. We argue, in contrast, that walking remains essential: it is the basis of who and where we are, the means by which we gather and separate, by which we first traverse territories and give them definition. Our understanding of space begins with the body, and the body is the first geometer, journeys being also a primary metaphor for the construction of memory and narrative. The second part of the book ends by comparing walking with other forms of locomotion, with the nature of roads and how we perceive them, and with the role of senses other than the visual, such as hearing, including the haptic experience of the body in motion.

Even if the active designer and the reader of spaces are both temporarily individuals, no individual exists in isolation. The third part of the book is about the social, and the way moving through space is shared through rituals, whether in the form of parades and pilgrimages or of our more numerous and mundane daily interactions, which can still be called ritualistic.7 The built environment is organised socially and is full of signals that carry the instructions for social conventions. At the start of Erving Goffman’s classic The Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life, he describes arrival at a Scottish croft and the preparation of the inhabitant before opening the door to greet the visitor – ‘to prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet’, as T.S. Eliot put it.8 This example is just Goffman’s introduction to a long series of entries that soon involves his foundational metaphor: frontstage versus backstage. In a restaurant, frontstage is the polite dining room, backstage the kitchen; in a garage, frontstage is the smart office where you pay money to a man in suit and tie, backstage is the workshop where men in greasy overalls disembowel your car. The metaphor can be applied to almost any building complex, differentiating front from back, formal from informal. There must be thresholds of some sort between these kinds of space, and further thresholds into the outside world, to mark divisions and transitions. Entering and leaving are not just physical acts but differentiations of territory, and also the basis of all our metaphors about inside and outside. Therefore, crossing thresholds is a fundamental experience and is tied up cross-culturally with what are metaphorically called rites of passage: birth, initiation, marriage and death.9 Even when thresholds are physical entities, their power and meaning are due to the rules under which they operate. The examples in Part 3 of this book are, therefore, about the relationship between space and social rules, about how buildings and landscapes frame rituals: rituals seen in the broad sense of shared and repeated human activities. Every society requires an established relationship between spaces and rules, with conventions that may be more local or more general.

The final part of the book deals with movement by proxy. When we talk about or illustrate movement through space, we need to represent both space and time, through oral or written descriptions, drawings of different kinds, physical models, photography, film or computerised projections. Obviously, such media limit and condition what can be expressed and communicated, and some offer advantages in one direction, some in another. Texts are good for narrative, unfolding in time, but they stress singular experience and fail to describe spaces as drawings can. Maps are always highly selective, tending to prioritise the values of their makers and commissioners and following conventions that are necessarily in some ways exclusive. Plan and section drawings show the anatomy of a built environment but need to be read with some skill to put it back into three dimensions, even more to imagine a fourth. Film, at first, seems an ideal medium to transmit what is visible and, at the same time, to allow narrative sequence, but its angle of view is restricted, and it has developed its own set of convincing but deceptive, techniques of cutting and splicing to create imaginary place, aided by clever concoctions of sound that further encourage our suspension of disbelief.

The conventions of plan and section have recently been somewhat subsumed in the computer by the three-dimensional model, which predicts the location of every part of a building design on cartesian coordinates with astonishing precision, and brings new efficiency and understanding to the processes of calculation and construction. However, although the model resides reliably in the circuits of the computer, magically available for specialists to work on, it has to be reduced to a visible form to be seen, normally on a two-dimensional screen. Plans and sections have, in consequence, become less iconic, while the computer fly-through, adding a fourth dimension, has gained in popularity. It leaves the imaginative skill required by drawings to one side, but gives the odd impression of not having one’s feet on the ground. It also plays into the hands of forms of perception developed and made familiar by the medium of television, creating a virtual world detached from our physical being and lacking all perceptual information apart from the visual, supplemented only sometimes by the auditory. A now rather old and familiar filmic convention illustrates this well: the transporter room of the Enterprise in Star Trek,10 which, as we soon deduce, allows Captain Kirk and his crew instantly to pass from spaceship to adjacent planet. What we generally do not ponder is why they need to go into the transporter room at all, given that they can be picked up from the planet at any point. And if the system works so well, why walk anywhere, and why bother to have doors on rooms? The implied loss of threshold and of self-propulsion here reveals the real passivity of the body as spectator watching the film, while the fizzing away of bodies on the screen is an efficient convention for a theatrical change of scene, avoiding the need for extensive and time-wasting footage about descent to the planet.

The experience of movement through space, once seemingly natural, straightforward and inevitable, has been neglected or sidelined in much architecture and planning over the past century, because of the great technical and economic changes that have overtaken our civilisation. There has been a consequent sense of anomie and alienation, a rash of dystopias in the visual arts, and confusion for many about where to be and where to go. At the same time, in many forms of discourse, metaphorical space has taken over from bodily space as if the two were the same, but ‘political space’ does not mean a building or a landscape, and, when people say ‘don’t go there’ or ‘I’m not in a good place’, it is an idea rather than a location that they are avoiding, a state of mind that is troubled. A better understanding is, therefore, urgently needed, and also a shift away from the idea that the experience of movement in buildings or in landscapes might be ‘just an aesthetic issue’. We are by no means against beauty and attempts to increase its occurrence, but we deeply regret its relegation to the margin, to something extra, ‘subjective’, ‘personal’ or merely ‘a matter of taste’. The subjective is often shared, and even taste is a social thing, as Pierre Bourdieu effectively showed in Distinction:11 it is part of a shared reality. We try, in this book, to relate the experience of movement in architecture to larger and more fundamental questions about how we can understand the world, find our place in it and maintain our health and well-being.

1 Many places could have served: this one was chosen because it had been studied in detail by Peter Blundell Jones in the early 1970s, also the period of the photos. See ‘The country town’ in Cantacuzino 1975, pp. 41–9.

2 Theodor Fischer in Germany, for example, but also Raymond Unwin, planner of Letchworth.

3 See Collins 1965.

4 The Charter of Athens was the result of the CIAM meeting of 1933: the tenets can be found in Conrads 1970, pp. 137–45.

5 Augé 1995.

6 Richard Long and Hamish Fulton are obvious examples. Rebecca Solnit discusses this in her History of Walking (Solnit 2007); Geoff Nicholson’s book is called The Lost Art of Walking (Nicholson 2010).

7 The Random House Dictionary includes the morning coffee break and handshakes among rituals, and Mary Douglas, in Deciphering a Meal (Douglas 1975), made good case for considering meals in general as rituals.

8 Goffman 1971, pp. 18–19. The T.S. Eliot quotation is from ‘The love song of J. Alfred Prufrock’, Eliot 1920.

9 See van Gennep 1960 (original 1908).

10 The US television and film science fiction series conceived by Gene Roddenberry in 1964 and first shown in 1966, which ran to 726 episodes (Wikipedia).

11 See Bourdieu 1984.