Initially, pain serves as a message of distress, danger or damage – a call to protect the area that hurts that is interpreted in the brain as “pain”.

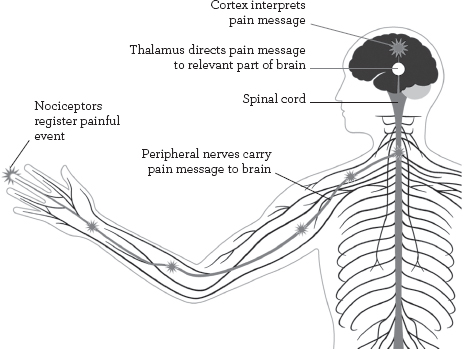

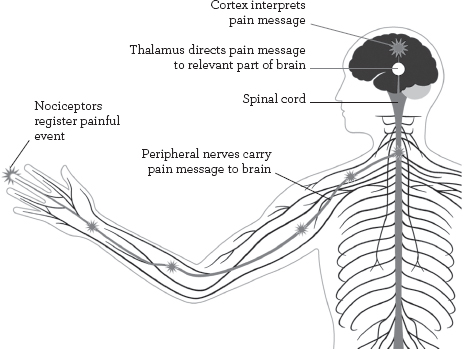

Something will have happened to stimulate or irritate tiny nerve structures called nociceptors (pain receptors) – possibly inflammation, chemical irritation, heat, or a mechanical event, such as pressure, stretching, cutting or tearing. The resulting pain messages travel to the brain via mylenated (sheathed) nerves, which carry impulses rapidly at 65½ft (20m) a second, and unmyelenated nerves, which carry impulses at 6½ft (2m) a second.

Nociceptors are found in most tissues of the body, in greater numbers where we are most sensitive. Each nociceptor has a threshold that has to be exceeded before it reports to the brain that there is a problem. This threshold varies widely, with a number of factors contributing to what the individual “feels”, and how he or she interprets that feeling. A major reason for the pain threshold changing is a process known as sensitization, which is explained later in the book (see pages 21–4).

HOW WE FEEL PAIN

Pain messages travel from the site of injury to the brain, where pain is experienced through a virtual body map.

Although the alarm messages that we perceive as pain usually start in the part that hurts, this is not where we actually feel pain. Instead, pain is felt in the brain, by means of a virtual body map (the homunculus) that resides there. If this seems strange, consider that many amputees feel “phantom”pain in the missing limb, long after it has been removed. Consider also that some pain does not even originate from where we feel the hurt. Pain messages arising from local areas, and travelling along nerves to the spine and from there to the brain, can be re-routed, so that the pain is felt somewhere else altogether. This is known as reflex, or referred, pain (see pages 18–20). For example, angina pain is felt in the left arm (and other areas) but derives from distress in heart muscles.

Pain can be acute or chronic. Acute pain derives from a condition that builds rapidly to a crisis, such as a sprained ankle, whereas chronic pain is longer-lasting and more deep-seated – for example, back pain resulting from poor posture over a long period.

The way we experience most pain is affected not merely by the physical processes that have caused it to occur, but also by our intellectual and emotional reaction to it. Much depends on the “meaning” that we give the pain, which we tend to process through our individual experiences and expectations. Take, again, the arm pain of angina, which is similar to arm pain originating from hypersensitive areas of the muscles of the front of the neck (the scalenes). Your attitude toward the pain would be very different if you thought it were a neck-muscle problem, rather than a heart problem. What pain means to us, and the circumstances out of which it emerges, can radically affect our perception of its potency. If we understand the cause of our pain, we are more likely to react to it in a constructive way.

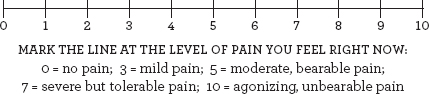

Pain is a personal experience – as difficult to measure and express objectively as hunger or thirst, happiness or sadness. You cannot say exactly how much a pain hurts, only that it is, for example, mild, moderate, severe or agonizing. However, your idea of what constitutes an “agonizing pain” may be very different from someone else’s.

You can use the calibrated line shown below as a template to incorporate in a “pain journal” in which you record aspects of your pain experience (see pages 36–9). By marking your pain level on such a scale each day, you can keep a check on how your pain is changing over time, perhaps in response to different treatments or changes in behaviour (such as exercise or diet).

Pain is sometimes positively useful. If you injure your arm, you know why it hurts afterwards. Days later the area may still be red and painful owing to the inflammatory process, without which the tissues could not heal (see pages 32–3). These healing tissues need to be treated with care so that they remodel themselves properly – the continued hurt is a warning to avoid doing too much too soon.

Sometimes, however, the cause of a pain is not clear, calling for expert investigation. In some cases, the original cause may be gone but its effects live on in a constant discomfort or worse. This occurs in conditions such as shingles (herpes zoster), after which burning pain can continue for years, serving no warning purpose at all. If you don’t know why something hurts, you need to find out.