At this very time, during the second half of August, the courtiers at Passau were intensely excited. For some, the approaching confinement of the Empress was the immediate concern; the question whether she would give birth to a son or a daughter, even though overshadowed by a crisis in the grand antagonism of the Christian and Moslem worlds, had sufficient significance in this age of dynastic politics. For others, the movement of troops from Germany down the Danube whetted their excitement most. The Bavarians had already gone through Passau. On 21 August 6,000 Franconian infantry arrived, travelling by water; 2,000 cavalry were soon to follow by land. The military authorities were naturally anxious about the concentration of these forces in Lower Austria because they knew, in general terms, that the Saxons were already in Bohemia, that the Poles were in Silesia, while Lorraine himself was moving west. Less informed observers still hoped for the appearance of 15,000 Brandenburgers and 5,000 from the Brunswick lands, to make up a total of 100,000 troops for the relieving army. It was not only a matter of transport, food and other supplies, but of the collaboration of so many ruling princes which preoccupied the government. On this point, the Emperor himself felt the gravest doubts. He wanted to recover the personal prestige lost by his abrupt flight from Vienna, and to assert his Imperial status. On the other hand he also wanted to satisfy and pacify indispensable allies and, except in a few moments of daydreaming, did not visualise himself as the generalissimo which his father Ferdinand III had been. In effect, he enjoyed the proudest title on earth, while suffering from an acute sense of personal inferiority in many matters. A long series of discussions followed, in which most of the Habsburg ministers and the Spanish ambassador pressed strongly for Leopold’s presence with the army. The nuncio disagreed: such a decision, he argued, could only irritate the other princes, who deserved credit for their determination to come to the rescue of Vienna.1 It would increase, not diminish, the dangers of useless quarrels over precedence. (The nuncio spoke as an expert: his correspondence is filled with the details of his ceaseless bickering at court to establish his own precedence over princes of the Empire and their representatives.) It was certainly true that an Emperor who arrived at camp with a retinue of thirty guards could only suffer by contrast with the panoply which the King of Poland and the Elector of Bavaria evidently intended to display. In fact, when the question of precedence did not affect the Catholic Church, Buonvisi blandly overlooked it. He thought that he had won the debate, when Leopold at length decided to move down the river to Linz.2 This appeared to signify that the Emperor and the War Council simply proposed to get closer to the scene of action; but Leopold wanted to join the army, without having fully made up his mind to do so or determining exactly what part to try and play in the coming campaign. Because the Empress signified her willingness to accompany him he was able to temporise a little longer. The whole affair was one example, among thousands in the course of a long life, of his chronic difficulty in making a firm decision.

On 25 August from 8.30 in the morning until seven o’clock at night the government, including the four senior court officers, three chancellors, and two presidents* of the great offices of state, travelled down the Danube as far as Linz.3 During the day Leopold wrote to Marco d’Aviano, who was himself coming over the Alps to the theatre of action, sent by Pope Innocent with the powers of a Papal Legate to bless and console the crusaders. Leopold, although anxious for yet more counsel, told Marco that he proposed to appear among the confederate princes and generals in order to stop quarrels between them. Then he reached Linz, and the court settled down again. Troops poured through from Germany, and he reviewed them. Max Emmanuel arrived by water, with a large staff which set the court-marshal a pretty problem in trying to accommodate their 600 horses. The old debate continued. Buonvisi urged his views once more, and apparently won over the Bishop of Vienna. Marco arrived on 2 September and also discussed the question with Leopold. Evidently it was understood between them that Marco, who left on the next day for Krems and Tulln, would advise the Emperor whether to proceed farther after he had sounded opinion at the military headquarters.

Momentarily Leopold seemed becalmed. On the 5th he made up his mind to go down the river again and join his army, although he had heard nothing from Marco. Then Prince George of Hanover arrived with his few followers, all that were spared from the powerful Brunswick forces in Lower Saxony. Then the Empress gave birth to a daughter, hastily christened Maria Anna Josepha Regina with the sponsorship of a single godfather, Max Emmanuel. Then a letter from Marco was delivered, and it said not a single word about the matter uppermost in Leopold’s mind. But he set off on the 8th. He left behind him the Empress and her household, and wrote once more begging for definite advice, at the same time admitting that he would wait for it.4 In his own wavering fashion he was moving with the current of the Danube, and the course of circumstances; he hesitated to enforce the autocratic will vested in him, and yet not his own. He must go, and he must wait; while other and lesser figures participated and determined, he waited. This agonising, pathetic pause in the most dramatic moment of his whole reign, took place on the waters of the Danube somewhere near Dürnstein, on the great bend of the river there; below the bend is the little walled town; and on the height above the river stand the ancient ruins of a castle in which the Anglo-Norman King Richard, Coeur de Lion, was imprisoned in 1193. From here there is an immense panorama stretching miles downstream as far as the western edge of the Wiener Wald. No contemporary source says that anyone was sent up the ridge to observe signs of action in the landscape; but on board his boat Leopold remained from 9 to 12 September. He received a letter from Marco on the 11th, and replied at once. He received another, dated the 11th, on the 12th and again replied. Leopold throughout expresses a complete faith in the future: this crisis, thanks to God and all the saints, thanks to the Papal blessing and the Capuchin’s presence in the army, will be surmounted. For the moment he repressed the alternative view, of the plague and the comet and the Turks as a part of a righteous judgment on himself and the sinfulness of man. But he still wanted to know whether the time had not come for the Emperor and hereditary ruler of these lands to negotiate personally with his allies and to show himself to his subjects. Marco said nothing; Leopold did nothing. The siege continued.

* One of these was Herman of Baden, who went further down the river in order to confer with Lorraine and Sobieski, and was present at Ober-Hollabrun on 31 August.

Starhemberg’s letter from Vienna of 18 August was still serene and confident, reporting that the Turks had made little progress in the past week. This was no more than the truth even allowing for the fact that our principal Turkish source of information, which would have boasted of any Turkish gains, has an unfortunate gap from 14 to 17 August. However the Master of Ceremonies, on the 13th, gives two important items:5 troops and commanders on the Danube islands were being brought round to reinforce the Janissaries and other units in the area in front of the Burg; while heavy rain, falling during the night, made the approaches temporarily unusable. His next entry, on the 18th, notes the Grand Vezir’s urgent order to the commander at Neuhäusel to join the army at once.

The Austrians also mention the rain but they were much more preoccupied by the works then being carried out in the Burg and Löbel bastions. New trenches and walls were thrown up quickly, to give better protection to the defenders when and if the Turks reached these inner works. The pressure on the labour squads was intense. Large numbers were absent and ill. Starhemberg reprimanded the civilian authorities sharply for slackness, and insisted on a reorganisation of the burgher companies. Meanwhile all through the week, in front of the bastions, the moat was the scene of violent fighting every day. The soldiers, taking turn and turn about under different commanding officers—Souches, Württemberg, Serenyi and Scherffenberg—held on to the Burg-ravelin, to various block-houses to left and right of it, and to parts of the counterscarp even in this sector. Elsewhere they defended the counterscarp fairly easily. The Turks slowly dug down towards the floor of the moat, desperately trying to extend the area under their control. Trenches and tunnels required first to be dug, then to be strengthened and covered with timbers and sandbags. A few feet away from them their opponents were digging in the same way, using similar materials. Miners on both sides endeavoured to site their powder barrels undetected, and to countermine. After earth and masonry had been displaced by an explosion small groups of men, thirty, forty, or a hundred, went over to the assault, sometimes in daylight, sometimes at night with the darkness abruptly dispelled by flares here and there. On one occasion (the night of the 16th), an Austrian sortie led by Serenyi and Scherffenberg managed to set fire to the Turkish galleries projecting from the escarpment opposite the Löbel, and sufficient damage was done to hold up the enemy for ten or twelve days in this sector.6 But foot by foot the Turks pressed forward; and on 18 August a much less effective sortie by the garrison troops, intended to push the Turks out of their corner of the ravelin, met with a decided repulse and resulted in the death of Colonel Dupigny, whose dragoons had been dismounted and now shared in the fighting. The consequences of the defeat might have been serious, and it was Starhemberg’s good fortune that the Turks were not quick enough to profit from it.

Between 9 and 19 August 12,000 florins were paid out for work and materials needed on the fortifications, on the 13th nearly 1,000 florins were paid to the artillerymen, and on the 19th the troops got their fortnightly allotment of some 32,000 florins.7 The first of these figures is exceptionally high, and is a fair indication of what was going on in the moat and on the bastions. On the 19th, as well, a small raiding party went out by the Carinthian-gate and was lucky enough to return with thirty-two oxen. The garrison also recovered that part of the ravelin which had been lost the day before.8

Indeed the administration in the city ticked on. The bitter and inch by inch struggle for ravelin and moat continued. The fears or hopes that something of a more spectacular kind would decide the issue were daily fed on not very substantial rumours and reports—like the rumour that the Turks were digging a tunnel right under the main wall into Leopold’s wine-cellars, or the report that Turkish cavalry were overrunning all the countryside north of the Danube after Lorraine’s regiments had marched away to the west.

On 25 August Starhemberg held an important conference with all his principal officers on the Löbel-bastion; immediately opposite the enemy had been steadily making further progress in the last few days and was coming, as far as he could judge, dangerously close. A major sortie was decided,

and accordingly about four in the Afternoon Captain Travers, and Captain Heneman of the Regiment of Souches and Lieutenant Simon of the Regiment of Beck, were commanded out upon this Service; who passing through the Sallyports, were followed thither by Count Sereni and the Prince of Wirtenberg . . . And Count Souches having at the same time undertaken another Sally, not far from the same place, the Enemy was forced to give ground; and the Prince of Wirtenberg pursuing closely into their Trenches without the Counterscarp as far as one of their Batteries, upon which were planted three Pieces of Ordinance, it would have been very easie to have nailed up their Guns, if our men had been provided with Nails, but the Turks beginning to rally and to increase in number, they thought fit to retire into the Ditch, still firing upon the Enemy that followed them. In this Action were lost about two hundred Common Souldiers on our side.*

With that account may be compared the corresponding entry in a Turkish version of the day’s fighting:

Before noon the Grand Vezir entered the trenches, and summoned to his headquarters Hussein pasha, Bekir pasha, the Aga of the Janissaries from Rodosto and the kethuda beyi Yusuf, as well as other commanders. He gave solemn warnings to them all, and ordered each one of them to do his utmost to bring the enterprise to a successful conclusion, expending life and property for the true faith. Then he returned to his own base outside the works. He granted the province of Eger to kethuda Ahmed pasha and the province of Maras to Omer pasha; he awarded them both insignia of the noblest rank. In the afternoon a mine was exploded in Ahmed pasha’s sector on the left (that is, opposite the Löbel), and the flame of battle flickered for over half an hour. It seemed as if the struggle would never end, and the fighting continued with incredible bitterness. The commander of the volunteers was given insignia appropriate to his rank.9

Noticeably, the Turkish writer has played down this affair, but on those occasions when the garrison had decidedly the worst of the encounter the Austrian diarists have far less to say about it.

Two days later Starhemberg tried to repeat this tactic, and formidable assault parties were thrown against the Turks in the moat, particularly in front of the Burg-bastion. But although his men did a good deal of damage the Turks were undeniably moving forward towards the main bastions at this stage, and gradually more and more of the ravelin fell into their hands; the latter was by now little more than a ruin, with heroic groups of Christian soldiers taking turns to defend it as long as they could also hold the entrenchment which gave access to it. That day and the next, a quantity of rockets were fired off from the tower of St Stephen’s at nightfall, in an attempt to warn Lorraine of the growing urgency of the crisis at hand. The volunteer Michaelovitz prepared to set out with one more dispatch to the world outside the city. The Turks welcomed those rockets as a sign of the garrison’s distress. ‘May the almighty Lord of Heaven obliterate the infidels utterly from the face of the earth.’11

At last the Turks closed in on the ravelin and, as they did so, began to concentrate their attack on the two bastions. On 2 September after slight rainfall, one powerful mine brought down a part of the wall of the Burg-bastion, and during the same night the post of fifty men under Captain Heisterman (of Starhemberg’s regiment) on the ravelin suffered terrible losses when the enemy set fire to the timbers around them. But although Heisterman had orders to retire if it proved necessary, he held on until he was relieved at two o’clock on the next day. Then, and then only, Starhemberg finally gave up the ravelin. For both sides it was the beginning of the end, and they knew it.

The defence, underestimating considerably the Turkish working-parties in the moat, was surprised by the suddenness of the next major attack. At two o’clock in the afternoon of the 4th, after a showery morning of relative calm, the great blow fell.12 Colonel Hoffman relates that a violent explosion shook the house in which he was just then resting. Like everyone else he rushed towards the Burg-bastion where Souches, taking his turn to command the post, had placed his men on guard behind the foremost works. The mine had torn a large hole in the wall to the left of the tip of the bastion—Starhemberg’s precautions having apparently forced the Turks to place their powder at some distance from the most vulnerable point of all—and Hoffman now saw the tops of the Turkish flags and standards coming into view through the breach as the troops climbed up to the assault. Thirty feet of the defences were down, cries of ‘Allah! Allah! Allah!’ mingled with the fire from batteries on the counterscarp directed at the wall and bastions immediately opposite them; and for the defence this was a moment of anguish and desperation. But it soon rallied. Some units concentrated on the steady employment of their muskets, others heroically managed to stop the gap with planks and sacks. They wheeled forward the ready-made ‘chevaux de frise’, made of these materials; they were reinforced by troops who were in any case preparing to relieve the guard at that time. They were not dismayed by the continual storm of bombs, stones, arrows, which continued to come at them from the counterscarp, nor by the very great number of the attackers who put to good use the multitude of tunnels and passages in the Turkish works to get from the approaches and down into the moat at alarming speed. The onslaught lasted two hours, Starhemberg lost 200 men, the enemy many more. Kara Mustafa had failed, when the day ended, to make good a footing on the bastion; but his opponents, rightly, were never more alarmed for the safety of the city. They could no longer hope to hold out indefinitely by their own efforts. This had been argued before. It was now incontrovertible, even by the boldest.

At one o’clock in the morning of 6 September, Kuniz in great agitation hurried off a letter to his government. He wrote that the Turks now believed on the testimony of ‘the servant of an Armenian doctor’—whom they had captured—that Starhemberg’s position was desperate. The garrison contained no more than 5,000 effective fighting men, they were told. The citizens and the military command were quarrelling. If the assault of the 4th had been pressed a little further and a little longer, the municipality would have offered to surrender.13 This news vastly encouraged the Grand Vezir, who determined to continue mining and cannonading with all his strength. Kuniz, in the Ottoman camp, was correspondingly depressed.

The Turks then turned to the Löbel.* Certainly, Souches had here taken immense pains to prepare for an attack. Forewarned by events on the Burg-bastion barricades were set up at all points, and careful arrangements made to avoid confusion; the duties of each of the guards were laid down in detail. But exactly at noon on the 8th two mines went off; the tip of the bastion and a part of the left-hand wall crumbled at once, leaving only a small portion of the masonry intact. (It was not large enough to give shelter to the defenders.) Up came the Turks, while different parties of the garrison fired at close range from the barricades on top of the bastion, as well as from the positions which they still held in the moat. The assault lasted a full hour, but possibly the extreme heat of the day helped to blunt its fierceness. In the end, the Turks retreated. The Habsburg officers took in hand a partial repair of the gaps in the wall; where these improvisations were weakest, fires were lit and kept burning to ward off the next onrush, and to impede the miners. As it was, the motive behind the tactics of Kara Mustafa and his advisers gradually became clearer. They had substantially weakened the Burg-bastion, then weakened the Löbel; they next began to advance their works across the moat on both sides of the ruined ravelin to the curtain-wall between the bastions, in order to mine it. The defenders had now to reckon that five mines were being attached to this section of their own works, while there were evident preparations to weaken the bastions still further. The stage was to be set for a general storm of the city on a grand and irresistible scale.

Moreover the garrison was tiring. Hoffman calculated that Starhemberg had only 4,000 fit men at his disposal by now.14 The commander dared not accept the suggestion that the casemates of the Löbel should be opened, so that a sortie could be made against the Turkish workmen only thirty or forty paces distant, as they prepared the charges at the base of the curtain-wall. Instead, during the next few days he redoubled the defences at the higher level, and even fortified the houses behind them. It was here that the troops were quartered in order to be ready for immediate action in every emergency, although they were tired and desperate men by now, complaining bitterly. Starhemberg did his best to avoid trouble at this crucial moment by a general re-allocation of commands and duties. But much more depended on the ability of the besiegers to keep up their pressure, and to make it overwhelming. Fortunately for those exhausted men in the houses behind the Löbel and in the Burg, they could not do so.

No less harassed were the civilians.15 The death-rate due to dysentery and other fevers crept up steadily during August, partly because food cost more and was harder to find; the official pegging of prices was increasingly disregarded. The municipality issued scores of instructions and orders, especially to the bakers, and tried to arrange for the fair distribution of bread which in any case became less and less edible, but found itself hampered by insistent requisitioning for the soldiers of the garrison. Donkey and cat meat took the place of veal. Yet one finds few notices of outright shortage. Instead there was great suffering just short of starvation, so that mostly older men and women died off. The overall sense of strain tightened sharply when September began, and Starhemberg’s grip on the civil population grew harsher as his position grew weaker.

Between 30 August and 4 September a fresh sequence of edicts attempted to mobilise more people for guard and labour duties. It was officially stated that such persons might be required to replace soldiers, when the soldiers were too tired or too few. Between 7 and 10 September Lieutenant-Colonel Balfour carried out a house-to-house inspection in order to muster further manpower: shirkers, and householders who concealed them, were alike threatened with the death penalty. Three more companies of unwilling conscripts were at length assembled on the Burgplatz, and immediately sent to work on the defences. Starhemberg also complained to the city council about burgher officers who failed to appear for duty on the watches to which they and their men had been assigned. Then on the 9th, burgomaster Liebenberg, ill and useless for many weeks past, finally died. On the very next day his incompetent nominee, who had been titular commander of all the civilian companies, was dismissed and replaced by a professional officer. He, a Major Rosstaucher, at once set about drawing up new and stringent regulations to enforce better discipline.

All this while, from the top of St Stephen’s tower the landscape around Vienna was under eager observation. Lorraine’s cavalry had reappeared opposite the city, fought an engagement with both Turks and Magyars, and then vanished again to the west. The Turks were also sending out large foraging parties which in due course came back. And they seemed to be redistributing their forces. Some moved in from the countryside to the suburb of St Marx, while others crossed over the Canal from Leopoldstadt and camped much closer to the Grand Vezir’s headquarters. From the tower, too, the garrison sent up its rockets at night to signal the safe arrival of Seradly or Michaelovitz. Away across the river the Bisamberg responded, while in the darkness between 7 and 8 September other rockets were seen rising from the direction of the Kahlenberg,16 on the Vienna side of the Danube—a first, breathtaking sign that an army of liberation had approached the heights of the Wiener Wald.

* From the English version ‘printed for William Nott in the Pall Mall, and George Wells Bookseller in St Paul’s Church-yard, 1684’.10

* On the left-hand side of illustration VI. The Burg-bastion is on the right.

On 15 August after the safe arrival of Gregorovitz and Koltschitzki, Lorraine at last had in his hands authoritative Viennese dispatches of the 4th, 8th and 12th of the month. He now knew more clearly the condition and prospects of the garrison. But Thököly’s marauders were still giving trouble in Moravia; and the irritating silence of the Passau government still vetoed a decisive move to the west. He reluctantly kept his station by the Morava, after sending forward the Grana and Baden foot-regiments under the Prince of Croy, with orders to prepare for the construction of a bridge at Tulln. Then Starhemberg’s message of the 18th, and his postscript of the 19th, reached him: the Turks had finally entered the moat in force. Next day, on the 21st, Lorraine set off with all his cavalry behind him.17

Angern—Wolkersdorf- Stockerau:* the road goes due east and west across the country, some twenty miles north of Vienna at its nearest point. From Stockerau, Lorraine himself went on ahead to examine the position opposite Tulln. The preparations for making a bridge here were well advanced; and the bridgehead on the other side of the river, the town of Tulln itself, had been reinforced by the few infantrymen he could muster.18 He returned to the camp at Stockerau and on the following morning, 24 August, detached a few troops to guard the plain farther north and east. The remaining regiments got ready to continue on their course to the west, when news suddenly came in that the enemy had appeared, not many miles distant; villages around the Bisamberg were on fire. Indeed, the Turks beaten at Pressburg a few weeks earlier were now moving forward again, out of Hungary and through the Little Carpathians, then riding west along the left bank of the Danube. With them came a sprinkle of Thököly’s Magyars, while volunteers from the main Turkish forces had crossed the river below Vienna to join them. Lorraine at once turned his men about. The enemy horse came in sight. Confused fighting began at two o’clock in the afternoon and the Turks were at first successful on both flanks, breaking through to the second line of Habsburg companies. But ‘our main body advanced in good order’ and its opponents retreated. The Magyars hurried back to the Morava, while other groups were observed trying to get away across the channels of the Danube. The boats (by which they had come) were miles downstream, few others could be found, so that possibly more men were drowned that day than were killed in the fighting beforehand. Such was the obscure, uncertain course of events sometimes labelled ‘the affair of Stammersdorf’, but the Turks evidently failed to interrupt the allied concentration north of the Danube. They tried next to rebuild the bridges leading across the river from Leopoldstadt, dismantled earlier by Lorraine. The water-level had fallen since then, so that the old timber foundations were accessible. Teams of Wallachian and Moldavian labourers duly arrived, and by the morning of 30 August a third of the main bridge was restored. Next day Lorraine struck. His own regiment advanced, and with the help of a battery swept the Turks out, making the bridge unusable.

Most of Lorraine’s troops were still at Stockerau, when he himself at last rode off to greet the King of Poland.

It was clear to all observers that the meeting of John Sobieski, Lorraine and Waldeck at Ober-Hollabrun, on 31 August, ended one phase of this campaign against the Turks and opened another. Leopold having forbidden Lorraine to move unaided against Kara Mustafa, it had been possible to concentrate simply on getting the Polish King and the German Electors into Austria. It was now necessary to choose a plan for the actual relief of Vienna, and to carry it out at once. The course of events at the end of August more or less settled the main issue. The Saxons and Poles were both present in force, some 35,000 men strong in Austria and Moravia, with 18,000 Franconians and Bavarians camped on the right bank of the Danube opposite Krems. The repulse of Thököly left Lorraine free to employ most of his 10,000 for the relief of Vienna. Even the difficult problem of transport across the Danube was nearly solved. Since those desperate days early in July, when the Lower Austrian Estates considered a proposal to destroy the bridge at Stein in order to keep the Tartars out of Krems, this crossing had proved its use to the troops and supplies coming down from the Empire. Moreover, two Turkish assaults on Klosterneuburg on 22 and 23 August failed ignominiously; it was therefore safe to proceed with the construction of another bridge at Tulln, half-way between Stein and Vienna. This plan was discussed at various times and by different authorities, ever since the Turks first settled down to the siege of Vienna. The Dutch engineer Peter Rulant reported in mid-August that the materials were ready, but that labour was scarce.19 Lorraine was insistent. Finally the military commander in Krems, Leslie, placed the business in the hands of a boastful but competent officer, Tobias Haslingen. By the end of the month the concentration of a massive relieving force south of the Danube, made possible by using the bridges both at Stein and Tulln, to be followed by the passage of this army through the Wiener Wald (along one route or another), was Lorraine’s immediate purpose. Sobieski had already agreed to the plan in outline.20

It is not easy at this distance of time to thread one’s way through a confused series of meetings, held during the next few days in order to settle outstanding questions.21 After a final banquet in Sobieski’s company on 31 August—‘there was hardly a man there, but you could tell he’d been drinking,’ wrote Le Bègue—Lorraine returned to his camp at Korneuburg, and Waldeck to the neighbouring village of Stockerau. On 1 September rain began to fall, and fell through the day and night following; the advance of troops and the parley of generals were both hindered. A meeting at the north end of the Tulln bridge, arranged for the purpose of a private discussion between Waldeck and Lorraine, was put off. John Sobieski, who had firmly determined to keep Leopold away from the army in order to claim the supreme command, still debated whether he ought not at least to go to Krems for a personal interview with the Emperor. In fact he waited, and met Lorraine once again on the 2nd. On this occasion Michaelovitz was presented to him; the stout-hearted messenger, surviving his perilous journey from Vienna, had already delivered to Lorraine the letters written by Starhemberg and Caplirs six days earlier. The need for urgency was heavily underlined; but, apart from the weather, there is little doubt that the Habsburg generals and Waldeck were still groping for an answer to the problem of the command. If the Emperor expected to preside over the consultations of his allies, let alone to accompany the army on its march to Vienna, the chances of an effective partnership with Sobieski would be sharply reduced. The King of Poland insisted, to a certain extent he was bound to insist, on securing the prestige of leadership for himself. At the same time the Saxon Elector, and no doubt General Degenfeld (representing Elector Max Emmanuel) were determined to preserve the independent command of their own troops.

On 3 September John George left Horn, in order to meet his allies by attending the conference which he was told would take place at Krems. Halfway he had warning that the other leaders had changed their plans and were conferring in Count Hardegg’s castle at Stetteldorf, where the ground finally drops away into the waterlogged plain through which the Danube flows. He discovered, when he arrived, that one important meeting had already taken place while a second was still going on: the first, between Lorraine and Waldeck and the Bavarian Degenfeld, and the other a larger gathering with Sobieski, Herman of Baden and various generals present. It seems that Lorraine, Waldeck and Degenfeld had framed a set of questions and answers ‘to be deliberated’ by the whole conference. The King of Poland made no difficulty in agreeing to the main proposals; nor, when it came to his turn to speak, did the Elector of Saxony. The new Tulln bridges were assigned to Lorraine’s and Sobieski’s troops, the bridge at Stein to the Saxons. They were all to cross the Danube not later than 6 or 7 September, the whole army assembling in and around Tulln. The combined force would then cross the Wiener Wald in the area between the Danube and the River Wien; and this decision finally scotched the plan favoured by Herman of Baden, of a detour round the hills in order to attack the Ottoman army from the south, possibly cutting off its line of retreat into Hungary. But the great men at Stetteldorf touched in guarded terms on the most delicate problem of all. ‘If his Imperial Majesty does not appear,’ it was concluded, ‘the supreme command will rest with his Majesty the King of Poland, each prince retaining command of his own troops.’22 The formula satisfied everybody, but Lorraine and Herman of Baden must both have realised that it was essential to keep Leopold at a safe distance. The Emperor, by his presence, would not compose discords; he would excite them. It must be assumed that they briefed Marco d’Aviano accordingly, when he reached Tulln a few days later.

After the conference John George moved west again to the village of Hadersdorf where he spent the next two nights. His regiments overtook him and reached Krems. On 5 September some of them were camped on an island in the Danube. They crossed the river, and covered part of the way along the south bank by the evening of the 6th, following behind the Bavarians and other troops of the Empire. At Tulln itself activity was intense. Haslingen relates, no doubt in exaggerated terms, how he had negotiated for a supply of money with the Estates of both Lower and Upper Austria, spent it freely on materials and equipment at the industrial centre of Steyr, and then succeeded in building two pontoon bridges at Tulln. Finally, with a labour force of 600 peasants and 1,000 musketeers, he hacked a way through the undergrowth of the flats between Stetteldorf and the river, so that troops could march down to the bridges without loss of time.23 The vanguard of the Poles appeared. Sobieski himself expressed admiration for what had been done, although he was preoccupied by the continuous repairs needed, which held up the wagons containing his supplies—a point of the greatest importance, because forage was very short in the ravaged country south of the Danube.24 He, like any spectator of the present day, was somewhat awed by the pace and weight of the main Danube current.

The concentration of troops on the level plain outside Tulln required three full days. The Bavarians, Franconians and Saxons took up positions nearest the Wiener Wald. The Habsburg troops drew up behind them; the Poles swung right after crossing the bridges and camped in the rear.25 In the town Marco d’Aviano bravely stoked up the enthusiasm for battle, and another council of war (on 8 September) discussed current problems, above all the dispositions for the march and for battle. A copy of an ‘ordre de bataille’ apparently drafted by John Sobieski has been recorded.26 If genuine (and it certainly contains some of the ideas expressed by the King in his correspondence) it must belong to an early phase in the negotiations. This document makes the distribution of troops in the camp at Tulln the basis of the order for battle. The Saxons, Bavarians and contingents from the Empire were to form the left wing marching closest to the Danube, the Habsburg soldiers the ‘corps de bataille’ in the centre, and to the Poles—coming up from their place in the rear of the camp—was assigned the place of honour on the right. It also stated that the infantry should move first in order to ease the progress of cavalry through heavily wooded hills, and then retire behind the horsemen when level ground in the neighbourhood of Vienna was reached. Guns were to be equally distributed between the different contingents, Habsburg, Imperial, and Polish; while German infantry units stiffened the Polish wing in return for the transposition of some mounted Polish troops to the left. One can only conclude that the council of generals, probably when Lorraine insisted, altered these arrangements in one fundamental particular; nor did the King of Poland leave on record any protest against the change. The Habsburg infantry, and part of their cavalry, were transferred to the left wing, with the Saxons placed next to them, while the Bavarians and troops of the Empire were posted to the centre. As before, the Poles remained on the right.

The routes to be followed across the Wiener Wald must also have been discussed, but no existing papers refer to the matter at this stage.

Meanwhile popular interest was focused on the enthralling spectacle of noble and princely volunteers from many parts of Europe congregating in this little Austrian town: like Prince George of Hanover-Calenberg, princes from Pfalz-Neuburg and Hesse-Kassel, and the English Lord Lansdowne. The Elector Max Emmanuel arrived to take command of his troops. He also claimed that his status in the constitution of the Empire gave him the right to lead the contingents from the Bavarian and Franconian Circles; in practice he was willing, on this point, to defer to Waldeck. Questions of precedence no doubt mattered intensely to individual rulers and generals, but it was the whole concourse of great men and large bodies of troops which impressed everyone, and in particular the King of Poland, who felt proud and pleased to act the part of generalissimo over them all.27

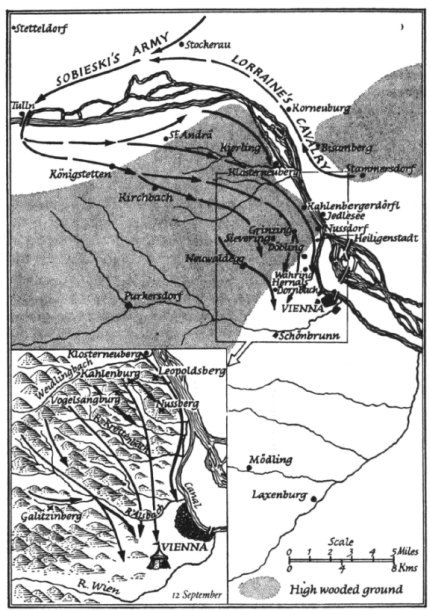

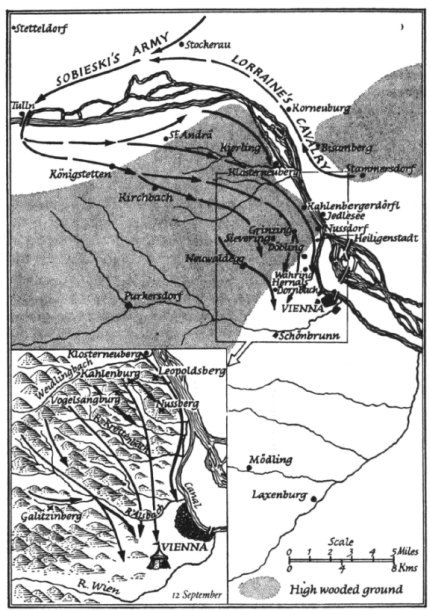

Lorraine had already sent 600 dragoons under Colonel Heisler to Klosterneuburg, and General Mercy now took other mounted troops to reconnoitre the Wiener Wald itself.28 While the army was still assembling at Tulln, several units began to move out of the camp. The main advance began on 9 September and by the end of the first day had reached the villages of St Andrä* and Königstetten, three miles apart, where the plain ends and the hills begin to rise up sharply; they were the two obvious points of departure for routes through much more difficult, thickly-wooded country. Lorraine meanwhile received news of the most recent Turkish failure to capture the Burg-bastion, and Mercy reached him again after a strenuous traverse across the Wald, having met with little in the way of Turkish or Tartar opposition. Lorraine’s staff now complained that Sobieski, previously so anxious to hurry on at all costs, held back; but the King may well have been reluctant to advance without the baggage (and troops) still in transit across the Danube. In any case Polish forces reached Königstetten by the evening of the 9th. That evening, officers spoke to foresters with a detailed knowledge of the ground ahead, the command sifted intelligence from various sources, and made its dispositions for the next morning.29

On the 10th, Lorraine at St Andrä split his forces. Some cavalry (including Lubomirski’s Poles) were sent round the northern edge of the hills, close to the Danube; others, including probably most of the German infantry, took the road across the hills. Both converged on Klosterneuburg. Sobieski’s cavalry, with his infantry well in the rear, began to climb up towards the villages of Kirling and Kirchbach. The intention was to make a rendezvous in the valley of the Weidlingbach,30 which lies beyond Klosterneuburg beneath the topmost ridge of the Wiener Wald, but the slopes were excessively steep, and particularly the haulage of artillery carriages and carts proved an arduous, heart-breaking business. The foremost troops on the left did indeed spend the next night on the Vienna side of Klosterneuburg, but others bivouacked on heights west of the little town, while the Poles were farther behind.31 They were still sufficiently in touch with forces in the centre, and the centre with those of the left, on sheltered ground which enemy forces did not venture to dispute. Sobieski moved ahead of his men, and conferred with Lorraine in full view of the great ridge which the army would have to climb.32 The suggestion that this could be attempted at once was turned down; but plans were made for the day following, 11 September.

During the night Lorraine, tireless in his tours of inspection, had second thoughts. At 2 a.m. he sent forward reinforcements to Heisler, and an attack was launched on the Turkish outposts which guarded the ridge from the ruined Camuldensian monastery at the top of St Joseph’s Berg (now called the Kahlenberg) and the Chapel of St Leopold on the Leopoldsberg, the two most northerly heights of the Wiener Wald. The Turks were successfully thrown out, and pushed back down the other side of the ridge. Rockets or flares shot up into the night to cheer the inhabitants of Vienna, five miles distant.

At dawn the troops began to move again, and the arrangement of the whole force becomes gradually clearer to us; even though, at the time, heavy rain and a storm must have obscured the view and depressed the spirit of everyone present. Heisler’s dragoons were already on the northern end of the ridge. Below them, on their left, were Habsburg and Polish cavalry moving alongside the Danube, pushing round the last shoulder of the hills fronting the river. Behind the dragoons were regiments of Habsburg infantry under Herman of Baden, and the Saxon infantry, followed by Saxon troops of horse commanded by the Elector himself. In the centre marched the Bavarians under Max Emmanuel, together with the Franconians under Waldeck. The foremost of all these contingents had reached the ridge by 11 a.m., holding it from the Leopoldsberg on the left to the Vogelsangberg on the right, with the Kahlenberg in the centre. Farther right still, regiments of Habsburg cavalry and dragoons, Bavarian and Franconian cavalry, were climbing up from the Weidlingbach and soon they too reached the top.

The Poles faced a much longer ordeal on the 11th. At the start they were farther behind, but they made progress, crossed the Weidlingbach, and by nightfall an indeterminate proportion of their cavalry was up on the high ground, fanning well out to the south. They were being followed by part of their infantry, but other units advanced very slowly; and a Polish artillery officer admits that more and more of his equipment had to be abandoned in the course of the day. In any case, his unit was still at the foot of the ridge when night fell. If there were more accounts like this, it is almost certain that we should have a picture of numerous contingents, German as well as Polish, moving many hours behind the foremost troops, leaving their carts and guns in the rear, climbing desperately up and forward during the hours of darkness, and then groping past positions which were already packed with other companies and squadrons.

Much earlier in the day, Father Marco had climbed the heights and written a letter to Leopold ‘dal monte a veduta di Vienna’, praising the good order of the men and the harmony of the generals, the stout action of the city’s beleaguered garrison and the providence of God. In front of him Christian volunteers were already skirmishing down the slopes, and brushing with parties of Janissaries who hastily started to dig entrenchments at various points.33

Marco’s harmonious generals and princes now inspected the great panorama to the south. Some of them had travelled hundreds of miles to see it, with the city in the middle-distance, surrounded by Turkish siegeworks and camps, the Danube on their left and the greater wooded hills to their right, with everything somewhat dimmed by the smoke rising from the guns, mines, and campfires of a siege in its final stages. Their principal concern was the ground between them and the walls of Vienna, and John Sobieski for one was grievously disappointed. Misled (as he thought) by maps previously submitted to him by Habsburg commanders who should have known better, he had expected the contours to fall away smoothly to the plain in which the city stood. Instead he saw precipices, ravines, dense woodland on steep slopes, and farther ridges in the immediate foreground, with the more level terrain far in the distance. He felt tempted to conclude that the whole direction of the army’s march in the last few days involved an error of judgment: either a long detour to the south was now advisable or, at the least, a slow advance inch by inch ‘à la Spinola’ would be necessary from the Kahlenberg, a tactic requiring time and caution. His French engineer, Dupont, supported and possibly inspired these arguments.34 In conference with the other generals, including Lorraine, the first of these ideas was firmly overruled; a full-scale attack from the ridge of the Wiener Wald was approved, but another council was called for the following morning, and it seems probable that a final decision about the timing of this attack was deferred. Sobieski also secured from Lorraine the transfer of four Habsburg infantry regiments to the right wing in order to give support to the Polish cavalry. Undoubtedly his nervousness was counterbalanced by a firm conviction that the Grand Vezir was a poor commander. He noted that the Turks had been foolish in not trying to defend the routes across the Wiener Wald, and even more so in not fortifying their encampments round Vienna. This was also Lorraine’s opinion. During the hours of darkness the King composed a long letter to his Queen, floridly outlining the situation, his hopes, and his fears; he gives the hour as three a.m. and only stopped writing when the time came to go and meet the other commanders again.35

* For these, see the maps on pp. xiv-xvii and p. 163.

* For St Andrä, see Illustration XI and, for the hills, streams and villages mentioned here, the map p. 163.

What had Kara Mustafa been doing? He made many mistakes in 1683, but the fundamental miscalculation was the span of time and the amount of effort needed to capture Vienna itself. He underestimated the tenacity of the defence. Therefore he concentrated all his efforts on the siege after the first month; therefore he neglected to take measures which would have safeguarded the besieging army. He took too little interest in the no-man’s-land of the Wiener Wald. He could have tried harder to occupy Klosterneuburg. He could have sent more Turkish cavalry, as well as the Tartars, to patrol the plain round Tulln, and it is possibly an oblique admission of this error that one Turkish writer of the period invariably abuses the Tartar Khan. He relates a story that the Khan was close enough to Tulln to observe the crossing of the Danube by Polish troops, and was advised to attack them. He refused, alleging that he had never been given sufficient support or encouragement by Kara Mustafa who always insulted him: he would not move to save this despicable general.36 In addition, the Ottoman command had not seriously attempted to stiffen its observation-posts on the ridge of the Wiener Wald, and only at the last moment were instructions given for ditches to be dug, and guns set in position, at selected points in the area between the eastern slopes of the hills and the encampments—with all their baggage and supplies—of the Turkish troops.

The Grand Vezir’s serious consideration of dangers threatening from behind the Wiener Wald dates back to 4 September. On that day a captured prisoner seems to have given him detailed, if exaggerated, accounts of the relieving army; the Poles and Germans combined were said to number 80,000 foot and 40,000 cavalry. Kara Mustafa at once ordered old Ibrahim of Buda, the one man who had boldly criticised the whole plan of campaign two months earlier, to bring all his troops from Györ to Vienna immediately.37 Four days later another prisoner was taken, who knew that Lorraine’s and Sobieski’s forces had crossed the river at Tulln, and were advancing towards the hillcountry with 200 pieces of artillery.38 The Pasha of Karahisar was sent westwards to get confirmation of this. Ibrahim arrived with 8,000 men and large supplies. The same evening and on the following morning (8 and 9 September) councils of war were held. Some commanders argued that the whole armament of the Turkish force should be employed to oppose Lorraine’s advance. The Grand Vezir disagreed, and determined to maintain full pressure on the city. On the 9th it was finally decided to adopt this second course. The Turks had very little experience in dealing with a difficult military problem familiar to western soldiers: the command of a force caught between a powerful garrison and a powerful relieving army. Probably no Christian general of this decade would have neglected to fortify the outer lines of a great camp from which an army was besieging a city.

Significantly evidence for the whereabouts of the positions west of Vienna, which were in fact fortified or entrenched by the Turks, is very uncertain. Something was certainly done to strengthen Nussdorf, a ruined village in the area farthest north, close to the Danube and underneath the Leopoldsberg. Other accounts refer to a redoubt constructed at Währing two miles southwest, the ‘Türkenschanz’ of which the alleged site survives to this day; but the Turks did not, apparently, attempt to defend it seriously.39 At the other end of the whole terrain, on the ridges above the left bank of the Wien, they strengthened a number of points with ditches and guns. Between Währing and the Wien, they hoped to make good use of the walls and buildings of vineyards on the lower slopes of the hills; behind these the ground was left open, presumably to give greater freedom of movement to the cavalry. In all, about sixty guns were withdrawn from the siegeworks and some 6,000 infantry. They employed in the field 22,000 horsemen,40 so that the relieving army was infinitely superior in manpower. The total Turkish force employed in the battle numbered perhaps 28,500 men a total increased but not strengthened by an indeterminate quantity of Wallachian, Moldavian and Tartar auxiliaries. The left and centre of Lorraine’s army alone numbered over 40,000 and the right wing under Sobieski’s immediate command was probably 20,000 strong. Lorraine and Sobieski together employed up to twice as many fieldpieces as the Turkish commanders.

There are signs that Kara Mustafa, between 9 and 12 September, altered his dispositions in a way which later enfeebled his power of resistance. By the 9th, enough information had been gathered from prisoners and from the Tartars to make preparations to deal with their opponents a matter of the utmost urgency. After a council of war in the morning, the Grand Vezir and other commanders toured and inspected the whole area west of the city in the afternoon; and they conferred with the Tartar Khan. The cavalry was divided into a vanguard under Kara Mehmed of Diyarbakir (5,400) and a main body under Ibrahim of Buda (23,000), and allotted the task of resisting Lorraine and Sobieski. The Grand Vezir was to stand firm in his headquarters at St Ulrich while troops under the command of Abaza Sari Hussein guarded both banks of the Wien. In this way the Grand Vezir’s camp was regarded as the core of the Turkish defence, with powerful forces protecting it on each side. On the 10th and 11th these preparations were intensified but fresh information showed that the immediate threat was bound to come from the north, from the area of the Kahlenberg and Leopoldsberg; units were then brought over from the other side of the Canal, while the great majority of Ibrahim’s troops moved into position behind the vanguard which was now in Nussdorf and Heiligenstadt (on the road between Nussdorf and Vienna).41 Accordingly, to meet the threat from the Kahlenberg there was a general shift of weight to the Turkish right, facing Lorraine. This probably weakened their defences elsewhere.

Few men can have slept soundly that Saturday night the 11th of September, whether on the hills, camped on the plain, or in the city. The particular preoccupation of the Christian leaders was with their artillery, which it took so much longer to move across the Wiener Wald than any other part of the army. Marco, writing earlier in the day, noted how they were waiting for it, and one Polish officer admits the delay.42 At last some pieces reached the ridge; and long before dawn on Sunday 12 September General Leslie was putting in hand the construction of a battery on the forward edge of the descent from the Leopoldsberg.43 An officer in charge there noticed that the Turks were preparing to mount an attack from the Nussberg (a hill immediately north of Nussdorf) on the half-finished works; he sent forward two battalions which were soon engaged. The Turks also occupied some of the higher ground immediately to their left, from which they threatened to advance, so that Lorraine had to send down more troops. Other Turkish forces pushed from Nussdorf up the valley between the two heights; Lorraine responded by setting the whole of his left wing in motion at about 5 a.m. In effect, the Turks had forced a decision on their opponents by the time Sobieski was making his way to Lorraine for the conference between them, agreed to the day before;44 a major encounter could not possibly be delayed. At last the hour was reached when the Christian army, to use the emphatic language of a contemporary Turkish writer, became a flood of black pitch coming down the mountain, consuming everything it touched.45

This great battle, for most of those who took part, was a confused series of separate encounters occurring within a wide area. Only occasionally did Sobieski and Lorraine, and to a far lesser degree Kara Mustafa, manage to impose a coherent tactical pattern on the fighting. As one man remarked: ‘there were places where the ground looked even, but on getting nearer we found very deep ravines, and vineyards surrounded by lofty walls’; and another: we fought ‘from ridge to valley, and from valley to ridge.’46 Troops constantly disappeared from view. The number of formal lines varied. Horse and foot got entangled. Units were moved across, on the sudden initiative of a single commander, to support others when these found themselves in difficulties.47 Certainly, all the serious fighting before noon was on the Christian left and Turkish right. More and more troops were thrown into the struggle for the Nussberg by both sides. Habsburg and Saxon dragoons under Heister, which had been coming round the shoulder of the Leopoldsberg, entered the village of Kahlenbergerdörfl, opening up a new line of approach to the Nussberg and Nussdorf. Then the Turks pushed back the Grana foot regiment, which was already in the outskirts of Nussdorf. More Saxon troops, both foot and horse, were ordered into the fray. Then, at last, Leslie managed to get a part of his artillery on to the Nussberg hill. At eight o’clock the Turks were still defending strongly the battered buildings of the village below it, making use of every scrap of stonework; but their predicament was a serious one. In the course of the next hour, Lorraine organised a devastating attack. Heister’s men arrived from the Kahlenbergerdörfl. Habsburg and Saxon dragoons dismounted to fight on foot. Finally infantry under Herman of Baden’s command entered the ruined village, and drove the Turks southwards. It was the first positive step forward in the final advance along the shore of the Canal towards Vienna, three miles distant.

Thereafter, in this sector the troops pressed steadily on from the valley in which Nussdorf stands into Heiligenstadt, another mile ahead. They tied up an ever-increasing proportion of Ibrahim’s available force. They made successful use of their artillery, causing great alarm in the enemy ranks. Nor did the Turks manage to seal off these troops from the regiments coming down and across the slopes farther inland—although for a short while they nearly managed to do so, until Lorraine closed an ugly gap—so that Heiligenstadt was occupied without much difficulty. Farther inland still Bavarians and Franconians continued to fan downwards, so that by noon Lorraine had established a front line which extended from Heiligenstadt to Grinzing, and Grinzing to the village of Sievering. Owing to a failure of nerve or lack of control in their command, the Turks had been unable to restrain themselves from fighting too many isolated and unsuccessful encounters on the slopes and in the gullies. Their shortage of manpower was aggravated before they withdrew to the more level ground, on which they might have attacked to better advantage.

These proceedings were watched with intense anxiety from vantage-points like the tower of St Stephen’s, in Vienna itself. Men observed the dense rows of infantry coming down from the ridge, disappearing and reappearing as the ground dipped and flattened. The guns would be pushed on ahead, firing at intervals; and then the troops closed up on them, moving forward thirty or forty paces at a time, a tactic repeated over and over again.48 At least in the centre, the tempo of the advance was determined more by the terrain than by Turkish opposition.

All reports agree that, on this day of blistering sunshine, there was a pause in the fighting at noon. It was a pause to recover breath, but the allied commanders were also determined not to weaken their position by pressing too far forward on their left before the right wing had begun to put pressure on the Ottoman defence. Concealed by the folding of the ground, and the thickness of woods, the pace of the Polish advance was difficult to estimate; it certainly appeared somewhat slow. But no one underestimated the importance of these troops, who were expected to come down the Alsbach, a tributary stream descending to the houses at Dornbach and ultimately to Hernals: a line of march which would bring the attack much closer to the main Turkish camp and to the Grand Vezir’s headquarters.

Some historians have blamed the Poles for their sluggishness, but it would be more helpful if evidence were found which explained why they were sluggish. Many Polish detachments were well behind the regiments of the left and centre already on the previous day, and can only have reached the upper ridges late in the evening, hungry and tired; there are no records which show how complete their preparations were during the night of 11th September. Even in the case of the German regiments put at John Sobieski’s disposal, it is known that they were in position on the Galitzinberg—well forward, and on the extreme right—by the time serious fighting began in this area, after midday; but it is not known whether they were already in position in the early hours of morning.49 Another possibility is that, when the council of war ended on the 11th Sobieski was by no means clear that the attack would begin at dawn, and therefore did not give positive instructions to his officers to make ready for action. The Turkish raids above Nussdorf, in conjunction with Lorraine’s purposeful itch to try and relieve Vienna without delay, altered the whole situation. But it took the King of Poland most of the morning, while fierce fighting continued on his left, to advance his right wing. He was already past his prime as an instinctive war-leader, a slow and very corpulent man who now lacked the energy to dominate a crisis on the battlefield; nor were the discipline and promptness of his aristocratic cavalry generals very marked, in spite of their many other military virtues.

Moreover, although it was a relatively simple matter to occupy the higher ground on both sides of the Alsbach, the descent of large numbers of men into the valley proved more arduous.50 Even then the greatest difficulty of all remained, to get them out of this narrow avenue of approach and reorganise them as a battle-formation, strong enough to meet a massive Turkish attack; the Turks were bound to try and interrupt and to crush the whole unwieldly manoeuvre. By one o’clock the Polish vanguard had reached Dornbach, where the woods and the slopes die away. They became visible to the forces anxiously waiting far away on their left. Shouts of joy and relief from the Germans saluted them, and dismayed the enemy. The heights on both sides of the Alsbach were in firm and friendly hands. From those on the left, the King himself directed operations, and he was in touch with the Franconian units and their leaders to his left. On the right Hetman Jablonowski commanded the Poles, some German infantry held the Galitzinberg, and a certain amount of support from artillery was assured. Fortunately the scattered Tartar forces still farther south were never a serious nuisance in this quarter. The future depended on the heroism and energy of the Polish centre under General Katski as it emerged from the narrower part of the Alsbach valley.

First of all select troops of volunteer hussars advanced. After a momentary success the Turks pushed them back, and then the conflict swayed uncertainly to and fro. It cannot be stated with any certainty whether the final result was determined by the steady refusal of these Poles on the lower ground to give up the costly struggle, or by the efforts of German foot soldiers coming down from the Galitzinberg, or by the extra forces which Sobieski threw in (aided by reinforcements of Austrian and Bavarian cavalry) from the heights on the left. After a fearful tussle the Turks gave way; their horsemen fled, and took shelter with the Turkish infantry and guns on a defensive position farther back. Sobieski now began to deploy his whole force on more level ground, having swung them slightly round so that they faced south-east. They were arranged in two lines, the intervals in the first being covered by contingents in the second. As before, Habsburg and Bavarian cavalry stood behind them on their immediate left. There were more Polish horsemen and dragoons on the right.

This achievement altered the whole face of the battle. The Polish wing of the army had caught up with the left and centre. It was a strong position, won after a hard-fought day. The great question, now, was whether to stop or to launch a further attack. Undoubtedly Lorraine himself wanted to press forward; and there is probably something in the famous story that when one experienced general, the Saxon commander Goltz, was asked for his opinion, he replied: ‘I am an old man, and I want comfortable quarters in Vienna tonight.’ Waldeck agreed. Sobieski agreed. They must have all based their hopes on signs of disorder and exhaustion in the enemy troops facing them. On one wing, the relieving army was two miles away from the walls of Vienna at their nearest point. On the other, it was a little more than two miles to Kara Mustafa’s headquarters in St Ulrich.

Preparations to mount an overwhelming attack were made along the whole front. At 3.20, in the fiercest heat of the afternoon the action began again on the left. The Turkish position here ran along the Vienna side of the Krottenbach (a stream reaching the Canal near Heiligenstadt) but soon turned to the south-west, where it faced first the centre of the Christian army, and then the Poles. The Turk’s resistance was ineffectual, and they soon began to withdraw rapidly to the left wing of Kara Mustafa’s defence. Some of the Habsburg troops at once made straight towards the nearest siegeworks of the city, others swung to the right. The same thing happened on the central part of the front: the Saxons, and then the troops of the Empire, pushed forward again—and swung to the right. The Poles had meanwhile thrown everything they had into their attack on the main armament of the Turks. For a short while the battle was doubtful; but the thrust of the Bavarian troops (under Degenfeld and Max Emmanuel himself), and then of other troops coming up from the more northerly sectors, weakened the flank of the Turkish position; the Poles finally plunged forward with their cavalry to sweep southwards. Here, other Turkish units made an obstinate stand;51 they had their backs to the River Wien, and when they finally gave way Kara Mustafa ran a real risk of being cut off by swift cavalry movements in his rear from any possible line of retreat. Meanwhile the bodyguards of the Grand Vezir resisted desperately when the Poles began to enter his great encampment from the west. On its northern side, Janissaries and other household troops were still fighting hard; the Franconians under Waldeck, and on his initiative, seem to have given Sobieski useful support in this final phase of the struggle. The total collapse of the Turks began, and when their soldiers still in the galleries and trenches in front of the Hofburg were instructed to come to the rescue of those in the camp, they fled. Kara Mustafa himself then retreated in perilous and disorderly haste, though he succeeded in taking with him the great Moslem standard, the Flag of the Prophet so vainly displayed on this bitter occasion, and the major part of his stock of money. Many other Turkish leaders and contingents had already left the battlefield several hours before; and so ended one of the most resounding of all Christian victories, and Ottoman defeats. By five-thirty the battle was over. Vienna was saved. The plundering began.

An Irish officer summarised the events of the day in his own terse way:52 ‘If the victory be not so complete as we promised ourselves it should, it proceeded only from the cowardice of our enemies, whom from morning till night we drove before us, beating them from post to post, without their having the courage to look us in the face, and that through several defiles, which had they any reasonable courage we could never have forced. The combat held longest where the King of Poland was, but that only added to his glory, he having beaten them with the loss of their cannon and their men; they have left us their whole camp in general, with their tents, bag and baggage, and time will tell us more particulars.’