At every crossway on the road that leads to the future, each progressive spirit is opposed by a thousand men appointed to guard the path. Let us have no fear lest their fair towers of former days be sufficiently defended. The least that the most timid of us can do is not to add to the tremendous dead weight that nature drags along.

Let us not say to ourselves that the best truth always lies in moderation, in the decent average. The average, the decent moderation of today, will be the least human of things tomorrow. At the time of the Spanish Inquisition, the opinion of good sense and of the good medium was certainly that people ought not to burn too large a number of heretics; extreme and unreasonable opinion obviously demanded that they burn none at all.

Let us think of the great invisible ship that carries our human destinies upon eternity. Like the vessels of our confined oceans, she has her sails and her ballast. The fear that she may pitch and roll upon leaving the roadstead is no reason for increasing the ballast by stowing the fair white sails in the depths of the hold. They were not woven to molder side by side with the cobblestones in the dark. Ballast exists everywhere; all the pebbles of the harbor, all the sands of the beach will serve for that. But sails are rare and precious things; their place is not in the murk of the well but amid the light of the tall masts, where they will collect the winds of space.

—MAETERLINCK

Who has not found the Heaven—below—

Will fail of it above—

For angels rent the house next ours,

Wherever we remove—

—EMILY DICKINSON

SOCIETY BY DESIGN / DESIGN BY SOCIETY

My heaven home is here,

No longer need I wait

To cross the foaming river

Or pass the pearly gate.

I’ve angels all around me,

With kindness they surround me,

To a glorious cause they’ve bound me,

My heavenly home is here.

—SHAKER HYMN

I who had sought afar from earth

The fairyland to meet

Now find content within its girth

And wonder nigh my feet . . .

And all I thought of heaven before

I find in earth below

A sunlight in the hidden core

To dim the noonday glow

And with the earth my heart is glad

I move as one of old

With mists of silver I am clad

And bright with burning gold.

—A.E. (GEORGE RUSSELL)

For all too long we have had a society designed by Happenstance. There are simply too many losers, which is inefficient and uneconomical from any point of view.

We need to build a society in which everyone wins. Losers are not good for business. The cost of having so many losers is tremendous in terms of happiness; in dollars for health care, famine relief, and prisons; in suffering and in wars—in wasted human potential.

We have the knowledge and resources to raise the wellbeing of all to unheard-of heights. We have in our hands the potential to create a blossoming of human culture—an Eden on earth and in the minds of human beings.

Will we be able to do it? Can we find the will to do it? For me, this is a design problem.

EDEN, HERE AND NOW

When I was a child, the word “design” meant to me something far off in a world where artists lived. Growing older, the word slipped a notch in my regard, as I came to think of design as a surface treatment—superficial, often cosmetic—cheap and gaudy, the dazzle aimed at conning a buyer. I was no longer in awe of the word but disdained it.

Then, observing the world more closely, I began to feel that this sense of the word was a misuse of the term by the commercial world. Design gradually came to mean to me that certain quality whereby a well-shaped spoon works. I began to find good design in quality work everywhere—in Finnish log houses, Dutch windmills, Eskimo fish-hooks, Indian moccasins, Swampscot dories.

Here was a joyous discovery. One of the most important qualities of life, that conscious shaping toward perfection, now had a name: design.

Still, the word’s connotations clung to the world of things. But as my concern for society and my understanding of its needs grew, I found myself reaching out for a phrase to convey the concept of a new form of education, and I began to think in terms of educational design. This idea grew into broader thoughts of family design, community design, and eventually life design, meaning the logical shaping of one’s own life. All this thinking finally knit itself together under one term—social design.

“Design” had now come full circle from my childhood, when I had associated the word with something especially beautiful, wondrous, marvelous. So “design,” as used here, implies not only beauty, well formed for use, but includes also the aspect of active human shaping for positive ends.

Good design is one of the most critical needs at this point in human history, not only practiced by those who are called designers but by society as a whole. We need a wider awareness of the need for good design in all elements of life, and we need to encourage all people to take part. The finest design for society will not be one worked up by specialists but a design created by the people themselves to fit their needs. Planners and designers are needed, but to help, not to preempt, the democratic work of creating a new society.

Only as all members of society become aware of their right and obligation to take part in designing the world of the future—and comprehend the need for everyone to take part, knowing that their efforts are truly welcome and necessary—only then can a genuine democracy exist.

EVERYDAY ADVENTURE

For many in our society life is pallid, dull, and insipid, lacking in any sense of adventure. How can we develop in our young the sense of wonder, of magical beauty in living and learning? A sense of excitement and eagerness to learn is natural in all children, yet we have found ways to stifle these enthusiasms in a very effective manner.

If we could be as efficient in supporting a child’s eagerness to learn as we have been in stifling this eagerness, this would revolutionize life as we know it.

This is one of the key questions pertaining to the improvement of human welfare: How can we build excitement and meaning into daily life—not with motorcycles, tennis, and TV, but with socially valid action?

Seldom are the young people in our society helped to see the ways in which they can be useful, experiencing the joys of working together. The Outward Bound movement takes its motto, “To seek, to serve, and not to yield,” from Tennyson’s poem “Ulysses”: Outward Bound has demonstrated some very positive approaches to this problem in programs that get young people sailing, climbing, canoeing, and desert trekking. Yet one drawback of these programs is that they are only a three-to-four-week exception from the norm. What we need is to increase the sense of adventure in daily life, all year long.

To seek, to serve—

and be a little yielding . . .

THE SMALL AND THE SUBTLE

Nothing is too small or insignificant to be well designed. In the society I would like to see, no detail would be too insignificant to receive its due consideration. Whether we make or buy the things we need, paying attention to what is small and subtle can make a great deal of difference in the world around us.

And good design need not stop with tools, dishes, and houses—it can also include our selection of food, of friends, and of those who teach our children. We need to consider good design in relation to family, community, and school.

For example, think about our children’s happiness. We are continually constructing “better” school buildings, and yet we rarely take happiness into consideration. If we are going to have a better world, we need to insist that the finest people are selected for the care of the young. We must see that they get the status, recognition, and salary that will help draw people of the finest abilities into teaching.

Good design would mean allocating our money and prestige to people rather than buildings and gadgetry, which would result in not only a healthier and happier society but also better gadgets, better medicine, better politics, and better management.

I think we should reward those who work with the youngest children with the highest salaries of all. Do you want better doctors? Improve kindergarten.

SUCCESS

Is it possible to build a society in which all people are successful? Yes, if we define success not in terms of competition—where for one to succeed, another must fail—but in nonviolent terms, wherein success means universal growth, health, and maturity.

In our society competition gets better press than cooperation. Why this happens to be so, I do not know. Society is actually based on cooperation to a greater extent than on competition.

With the vast mental ability that we collectively possess, can we not develop a definition of success that will encourage each person to develop to the fullest of his or her capacity? The more people who become successful in this nonexploitative way, the more successful will be the society we live in, improving the quality of life for all of us.

Even in our highly competitive society, children absorbed in creation seem oblivious to their surroundings. Only after they have finished do they look about to see what others have done. Alas, that’s when they so often begin to feel judgmental and self-conscious.

A number of years ago I took a traveling museum of Eskimo culture to Eskimo villages on the coast of the Bering Sea, with the purpose of giving the villagers a chance to see some of the beautiful examples of their culture that were hidden from them in museums. From December 1969 to April 1970, I visited twenty Eskimo villages and put on approximately seventy programs. To enable the Eskimo children to get into closer contact with the art of their people, we let each one choose a slide of an Eskimo print and project this onto a sheet of paper. They paired up to trace their images with felt-tipped pens, then laid the paper on the floor to color it. How delightful to see the beauty of their collaborations and the loveliness of the cooperative art the children produced.

SECURITY

If we are to design a world without violence and prejudice, we must develop ways to help people become more confident, aware, and secure. The less secure we are within ourselves, the greater our need to put others down—to try and make ourselves feel superior.

The Darwinian notion that ceaseless competition promoted the survival of the fittest individual has by now generally given way to the understanding that evolutionary success was due to the survival of the fittest community through interlocking cooperation.

—KIRKPATRICK SALE

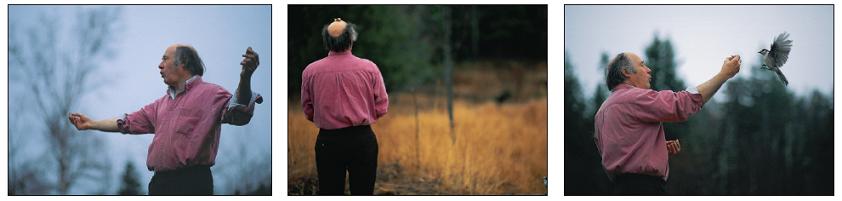

D. Porter

“Birds Startled by Spirit,” drawn by Lucy, colored by the children of Hooper Bay, Alaska.

Putting others down is a sick response, a blind, short-range, unhealthy response, increasing the likelihood that prejudice will be used on us in return. One way of helping build confidence and thus counter the spiral of violence in everyday life—which culminates in warfare—is to help others to gain a closer, more sensitive relationship with their environment. The resulting knowledge and sense of belonging are a strong antidote for insecurity.

It helps my thinking to imagine society as an extension of myself—as my social body. Anything I do to harm that body does harm to me. My neighbors’ poverty is mine; their need is my need, as well. And all prejudice, all violence, all hatred that I send out into the world returns to me. John Donne crystallized this for us all by saying, “. . . any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankinde; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

SEEKING THE RIGHT DISTANCE

In everyday life, there is a great deal of unnecessary, avoidable friction and violence among people. One remedy—a design solution—is to look at the world differently.

For example, take the platitude that we should love all people. Love is often presumed to mean being close, in continual contact. Couples assume that they should want to be together all the time, and when they begin to dislike such constant closeness, they fear that some quality is lacking in the relationship.

Likewise, some “intentional communities” seek to live in togetherness and complete sharing, and when the members can’t handle this they feel they have failed.

Or older couples, with happy lives and families behind them, will suddenly have more time together than before, and may find their spouse’s nearness oppressive.

While the resulting separations might be blamed on lack of compatibility, sensitivity, and caring, the desire for more privacy is wholly normal under the circumstances. For any two people, there is an ideal distance in the relationship. This is like the attraction between two planets. At the proper distance they keep orbiting, but if they approach one another too closely, they collide, and if they get too far apart they drift away.

This is neither good nor bad, but simply the way things are.

Finding the right distance takes sensitivity and understanding on the part of each one in a relationship, and this ideal balance between intimacy and independence varies over time. Some people we can see once a year and have a delightful time, whereas twice a year would be wearing. Others we can meet weekly and enjoy a stimulating and mutually supportive relationship, but were we to share the same house the effect would be bedlam. Some people can live extremely closely all their lives—working, eating, sleeping together. Others can reside happily together but need to work apart.

The newlyweds who understand this will realize the hazards of living too closely together, and instead of being threatened, they will happily seek the right distance in their relationship.

The community that recognizes this will likewise not be threatened but try to find the right spacing in its relationships and obligations. Often it is more effective to begin with more distance and to slowly come closer by degrees. The opposite approach of beginning relationships too near and adjusting by backing up seems to generate more hurt feelings, self-doubt, and insecurity.

Here is an opportunity to use the resources of good design. A couple coming to retirement knowing that changing circumstances will affect closeness and distance in their relationship can address the potential danger; they can avoid the pitfalls and rearrange their lives, seeking the needed balance. Recognizing such characteristics in human relating can lift the problem out of the emotional realm, removing the distractions of guilt and allowing us to rationally arrange the spaces in our lives for our mutual benefit.

But let there be space in your togetherness

And let the winds of heaven blow between you—

Sing and dance together and be joyous

But let each of you stand alone

Even as the strings of the lute are alone

Though they quiver with the same music.

—KAHLIL GIBRAN

Every child has a right to a family with a purpose.

This is just as important as food and affection.

The members of the family do not necessarily do the same work, yet they can be together in spirit, united in a feeling of camaraderie and teamwork.

HOMEMAKING

So much—words and conceptions—needs rethinking. So many of our values are dependent on the perspective of the times, which is often little more than a mix of passing fashions.

At the moment, throughout the United States, homemaking is looked down upon as a rather old-fashioned avocation. In reality, this is the most important profession and can be the most exciting of all.

It is sad that the true meaning of homemaking has been so misunderstood. In most communities it is now difficult for a young girl (to say nothing of a young boy) to grow up with the goal of becoming a homemaker. This prejudice has come about because some people have a bad experience with homemaking, feeling confined and circumscribed by the obligation to tend the home in lieu of a professional career. Without a doubt, any social institution can be misused.

Even so, a Turkish proverb says that it is shortsighted to burn your blanket to get rid of a flea. The home is our most important social realm, and unless we give the home the respect it is due and stop the incessant erosion now taking place, we will suffer irreparable loss.

The home is the center of education and emotional security, two of the essential elements of a healthy society. More and more, the functions of the home have been taken over by the school, but a school is no substitute for family, no matter how fine the instructors or expensive the equipment.

“The hand that rocks the cradle rules the world” is an avowal glibly repeated but given little heed. But the hand that rocks the cradle does rule the world, if not for good then for ill.

And unless the bearer of that hand perceives the honor, beauty, and responsibility of the role, the effect as often as not will be discord. There is no foundation more crucial than the sensitive care of the young in building a sane society. What mental insolvency has overtaken us that we can allow the core of our culture to be so denigrated and weakened? What a failure of design!

Far better to burn the house to the ground and live in a cave than lose your sense of wonder and privilege in making a home.

We started leaving the home to go to work in order

to support the home. We have been doing this

for so long that we have forgotten the purpose

for which we sold ourselves in the first place.

CRADLING IN NEW TRADITIONS

The small farm family of a hundred years ago provided most human needs. People sold little for cash and bought little. Life was hard but in many cases happy.

As with Frost’s two roads that diverged in a yellow wood, in advancing from those small farms we had two roads to choose between. One path was to abandon the farm and the skills of husbandry in favor of industrial development, allegedly to make life less hard physically. There was another path that could have been taken: we could have retained our homestead life, with its tremendous potential for human development, and applied our scientific and technological skills to make life on the homestead easier and less isolated. Now some in this country are moving in that direction, not back to an antiquated way of life but forward to a blend of the best of the past with the best of today.

It is with such blending that social design is concerned. Not “back to the land” but “down to earth.”

For emotional stability we need traditions to lean on. The extent to which we can alter our customs and still feel emotionally secure is probably quite small. Many people evidently relish change, but we change too many traditions at our peril.

This does not mean that when we see an unhealthy tradition (such as going to war) that we must accept it; but for all traditions we deplore and wish to change, there are myriad others that give us comfort and continuity.

As traditions are so helpful in innumerable unseen ways, we need to design society in a way that gives positive traditions emphasis.

In an ideal society we would continue to see the young rebelling against traditions, even these positive traditions, which later, upon more mature reflection, the former rebels would find valid.

Have you considered the most essential geographical factors in your child’s life, or in your own?

What is most important in your lives: The land?

The sea? The sky? The desert? The forest? Or is it the convenience store? The sidewalk? The parking lot?

The highway? The TV set? So often a house is chosen for its neighborhood, for its nearness to a good school, or for the social status it carries. Imagine how fine it would be instead to choose a special tree or a stream for your “comforting neighbor.” Why not resolve to be near a certain hill, a grove of trees, some handsome ledges, or a giant boulder standing up to the sky, and then design and build a home that fits both you and the surroundings?

FOLK WAYS AND “HEALTH FOODS”

Designing a new culture is inevitably a self-conscious process, not without risks of excess. An example of the danger in creating a self-conscious culture to take the place of a culture supported by folk ways is our present, notably self-conscious concept of diet.

As we’ve lost an understanding of healthy traditional sources of nutrition, modern people are left to their own guesswork to decide what represents a balanced meal. But the resulting judgments are seldom adequate and, considering the impact of slanted advertising, are rarely our own.

Under pressure of marketing, and the widespread poisoning of land and food with “preservatives” and “fertilizers,” the average person has little chance of choosing sensibly. The only alternative seems to be to become very self-conscious about food. By this means some few people learn to live healthily, while a great many others go to extremes—all carrot juice, or no bread, or all brown rice and no dairy products.

It is nearly impossible for a society to acquire a naturally healthy diet without guidance from traditions. We need, therefore, to carefully examine our traditions and keep the best of them in practice.

I would by no means argue that all folk diets are good, but learning to create a well-designed diet that in time becomes traditional would correct the excesses and oscillations of today’s self-conscious food fads. Who has time to measure every calorie, test for every vitamin?

But for a new traditional diet to come into being will require redesigning the care of our land, soil, and animals, as well as our legal and moral codes, which even with supposedly good intentions are quite unable to halt the adulteration and poisoning of foods.

We run risks in self-consciously re-designing our

family life, our houses, and our communities, but we

have no choice. With all our shortcomings, we must

apply conscious effort to the improvement of life for

all, with the hope that our efforts, applied over a long

enough time, will result in designs that provide a sound base for future tradition.

ENCOURAGEMENT

The main thrust of my own work is not “simple living,” not yurt design, not even “social design,” although each of these has importance and receives large contributions of my time.

Yet my central concern is encouragement—encouraging people to seek, to experiment, to design, to create, and to dream.

The only hope I see for our survival is to encourage the fullest development of all minds. Safety, truly, lies in numbers. One of these minds may find a brilliant solution, but even more certain, when we have more minds concerned, any challenge shrinks proportionally. The solution to our greatest problems may simply be involvement.

In the past, we looked to experts, to leaders, to national heroes for knowledge and guidance. To continue doing so means accepting a paternalistic way of life that holds us in a state of permanent adolescence.

And deferring to the experts is tremendously wasteful, stifling the imagination. We deny ourselves the joy of full development at a time when we’re in need of all the creativity we can muster to solve the desperate problems confronting our world. All these leaders and planners, however wise and skillful they may be, are simply no match for the challenge.

As an analogy, think of a child lost in a forest. We can send out an expert. A good tracker, given enough time, might find the child, but perhaps it will be too late. One person can’t cover enough ground. Instead, we recruit as many people as possible, as quickly as possible, to comb the countryside.

Expert knowledge is certainly needed in every area, but too little concern has been given to the value of stumbling. If enough people are searching—stumbling as they may—we will make many discoveries, and the stumbling diminishes as our searching skills get honed with practice. There is also great value in all of us realizing that our efforts are worthwhile, that we are needed, and that our abilities can be improved with use.

We need to design our responses to society’s emergencies to involve as many people as possible, and not be afraid of some inevitable stumbling.

I remember a time in my life, about fifty years ago, when after growing aware of the state of the world, I became greatly depressed. There was absolutely no way I could see that society would avert catastrophe. Nearly everywhere there was pollution of air, water, and minds; there was crime, poverty, political corruption, war, and poisoning of land and food. I viewed the mass of humanity as easily duped, with people willing to sell themselves for material gain while remaining provincial and violent. Democracy had become a system in which the many were manipulated by the few.

Yet slowly it became clear to me that the basic stock of humanity was sound, although the “democracy” I saw around us was not democracy at all but a distortion. As I became more aware of our untapped potential as human beings, I began to grow in optimism and belief in our latent ability to solve our problems.

I continue to feel that only a minute percentage of our potential has been developed. I am not concerned here with what economic, political, or social system is best. I am concerned with education—the full development of human beings.

The goal of social design is to improve the quality

of life on earth. The greatest hurdle is disbelief

in our own potential—learning to believe

we can design and build a better world.

If we can find ways to help one another—especially

our young—grow to full, sensitive, creative

adulthood, we will not need to concern ourselves with what specific style of government or economic system

we need. The coming generation will be so much better equipped that they will be able to design the new institutions and ways of life needed.

FINE THINGS

Most of us enjoy having fine things. How we define “fine” is going to affect greatly whether we live lives of quiet exploitation or of fairness.

For instance, having a fine house can be a matter of status, of expense and extravagance, or it can mean having the best house for you and your needs, a home that you design and build, a home that is fine because it is simply just right.

Having nice things does not have to mean having expensive things. The quality of a thing comes from the knowledge and beauty it carries more than from its expense. Having one of the best pancake-turners in the world is possible for anyone who finds out what constitutes a good pancake-turner. Money need not enter into the equation.

If you put many such small, incremental elements together, you can create one of the finest homes possible.

It is these little elements multiplied many times over that make up our daily world. The impact of subtleties upon the quality of our life and work is incalculable. And the more that good design surrounds us, the easier it becomes to design well. Remember, the chief elements in good design are sensitivity and care; expense is a relatively minor factor.

I am done with great things and big things, great institutions and big success, and I am for those tiny invisible molecular moral forces that work from individual to individual by creeping through the crannies of the world like so many rootlets, or like the capillary oozing of water, yet which, if you give them time, will rend the hardest monuments of man’s pride.

—WILLIAM JAMES

The concept of social design implies change—the rebuilding or reshaping of something, a process of transformation. Imagine what would happen if three hundred million people were concerned with building a better world! This would be a social revolution such as never before. The key difference between such a massive awakening and our present circumstances would be the realization on the part of huge numbers of people that this is their world: that the world can be changed, and that they can, should, and must have a role in redesigning that world.

For this to occur, designing would need to become like reading and writing, eating and sleeping, normal and familiar to everyone.

DESIGN BY AND FOR MACHINE

Of course, the end result of a better world will be as much a consequence of the process of seeking as it is an outcome of specific design ideas.

And unless design becomes the shared imaginative domain of all, we will continue to be exploited by the designers dedicated to commercial interests.

An aware public cannot be sold shoddy goods, ranging from tableware that is hard to wash because of “floral” ornaments and school programs that do not foster education, to nuclear power plants that cannot be accommodated by the environment and wars intended to “save us from our enemies.”

We are constantly manipulated by design. Industrial production has been a boon in providing many needed things at a lower cost, but unless we are alert we’ll let the machine start teaching us design. For instance, machines can be used to create any form of chair we like, but commercial interests can make more chairs (and more money) if the simplest design for the machines is chosen for production. So we end up surrounded by furniture designed to fit the needs of machines.

An example is the commercial slat-back chair with turned legs and rungs and a woven bottom. This chair has been made by machine for so long that it has become the norm for its type. But the person who wants to make such a chair by hand rarely questions the need for a lathe. It is possible to build a perfectly good chair with no lathe—the “rounds” do not need to be round or turned. All the necessary parts can be shaped with a knife, an axe, or a draw knife. Yet industrial production has so controlled the design of chairs that we now have a difficult time imagining how the form might differ if a chair were handmade.

A CHOICE OF ENGINES

Once or twice a week, I go forty minutes by canoe to get supplies. Some people think it strange that I don’t use a motor and thereby do the trip in fifteen or twenty minutes.

I enjoy the paddle. This excursion is one of the most relaxing and thought-provoking times of the week. I not only can see an osprey flying, I can hear it. And the exercise feels good. I have no argument with the use of motors, but they are not applicable in all situations. They are not a better way to move about, just another way.

As I write I can hear the deep throb of a lobster boat coming to haul traps in the bay. The engine makes good sense, in the right place. To tend four hundred traps a power boat is a necessity, but to tend five traps it’s a bit ridiculous. As with everything, a sense of proportion is necessary.

We need to design and select tools to fit our specific needs, and we need to select and design a technology to fit society as a potter fits a glaze to a bowl. In many cases, a technology that was designed for mass production is not well suited to a homestead. Likewise, agribusiness techniques are not needed or appropriate in the home garden. A table saw is not a necessity for making a cedar chest. And I can’t think of anything more ridiculous than an electric can opener.

IN SEARCH OF KEYS

The world is in such a crisis that we need to seek out key areas on which to focus our attention.

Keys work like catalysts, whereby a small amount of effort brings about a large result. We need to locate, define, and concentrate on areas wherein a modest initial effort will effect a broad and positive social change.

In our prejudice, our nationalisms, our violation of minds in schools and jobs, and our distorting of minds and bodies through industry and warfare, we have proof that our present-day “managers” are incapable of designing a fully productive, healthy, and happy society. When we reach social maturity, our citizens will do their own thinking and designing, no longer delegating that role.

If I appear to discount or underestimate the value of experts here, my apologies. Experts are needed as never before. But only by complete and genuine development of our whole people will we find the raw material we need to transform the world.

And a word of respect is due for an ancient kind of expert, the sages. Often their knowledge is of a general nature, gained in breadth of perspective over time. They continue to have much wisdom to share.

One contribution they make is encouragement. Inspiration is as vital as knowledge. Support from those who have gone before provides a special sustenance. In searching for a solid footing from which to approach the task of social design, my life is greatly indebted to the encouragement and example of several sages, old as well as wise.

Dead Time

“Why not get some horses?”

Comes over the water,

From a 30-foot lobster boat

With 300 horses,

To my 20-foot canoe with

A one-man cedar engine.

It’s a two-mile paddle to haul supplies

By rock-bound shore and gnarled spruce.

Osprey “float” above with sharp cries.

A startled heron croaks displeasure

Waiting for the tide to drop.

If lucky—there may be otter kits

Playing in the shallows

At the tide rips.

An eagle perches on a snag,

Loon laughter lilts over the long bay,

A seal looks me over.

A motor would take half the time—

But, what with mounting it,

Feeding it, and keeping it in tune,

Would there really be a gain in time?

True—I could go when the wind is

Too strong to paddle

But that is a non-problem.

The racket, the stench, the poisons—

There is the problem.

Oh—I could still see (most of) the birds

But not hear them

And the otters—they’d be long gone.

The paddle—lovely yellow cedar—

Carved on a beach in the San Juans,

Has served me well these thirty years.

While paddling the brain does delightful things,

Each moment a surprise—a treasure.

Motoring puts all that on hold,

Thieving those precious minutes—

My brain turned off:

Dead time.

I have long admired certain communities for their design of a common life, the Shakers and Doukhobors, in particular. Yet rather than defining solutions for the present according to Shaker and Doukhobor ways, chiefly I value these older models for the way they stimulate and challenge us to go further.

Those who guide us, who inspire us, having gone our way before, are now partners with us in building a better world. Any success we have is theirs as well as ours. To copy or imitate them should be only the beginning—the apprentice stage of life. It is fine to think, “What would a Shaker do? What would Scott Nearing have said? What would Gandhi have thought?” These are good exercises for the mind, a way of weighing ideas and contemplated actions, valuable so long as we do not follow anyone blindly.

Only by standing on their shoulders can we build a better world, but we should use the wise as advisers, not masters.

Learning to walk requires some stumbling

and falling.

APPRENTICES NEEDED, NOT DISCIPLES

For many, the knowledge of a Jesus, a Lao-tzu, a Buddha, or a Gandhi is complete and unassailable. But we do them and their vision a disservice when we follow them rather than using what they have taught to build upon as we strive toward our goal of a better society.

When we merely follow another, we take a potentially creative mind out of service—our own. We tie up a natural resource, just as much as when we put away money in the mattress.

We don’t need more disciples, we need more apprentices, the difference being that an apprentice serves as a follower only temporarily and is expected to go on and work independently. Wise apprentices recognize that the masters are always a part of them, that within them is a partnership of apprentice and master artisan, including all the other masters that came before.

Good apprentices know that they are in the process of becoming masters and that as responsible artisans they must seek to improve upon the knowledge entrusted to them and go further.

As apprentices we are not better than those who went before. We are a part, an extension of our predecessors, the newest buds on an ancient, living tree. If we do not reach up to the sun and down into the soil for nourishment to help the tree grow, we have not been faithful to the trust invested in us.

It is always easier to take the words of a Jesus, a Gandhi, a Marx, or a Confucius as constituting Holy Writ. This involves less reading, less study, less thought, less conflict, and less independent searching, but it also means less growth toward maturity.

CULTURAL PARENTAGE

There are many kinds of seeds in each of us. Usually we think in terms of a person’s genetic inheritance. I like to think in terms of cultural parentage, of intellectual inheritances—the ideas and values bequeathed to us. Perhaps it is good to ask ourselves: “Who are my brothers and my sisters?”*

We have known in our era a number of brilliant minds, flowers on the tree of human knowledge. Eric Fromm is one example, Carl Rogers is another, and still another is Abraham Maslow. These people were not followers. They brought new knowledge, deep-rooted in the wisdom of the past, from many sources.

We need knowledge brought forward from the past, collected, studied, experimented with, and blended together with modern knowledge for the creation of a new culture. Cultural blending has been an operating force in human affairs since one tribe first met with another.

Learning from one another is natural. Each group of people in the world is a repository of folk knowledge that is their inheritance from previous generations. Such knowledge is a valuable resource for all of humanity. Whether this be knowledge of child care, gardening, human relations, or tool design, such knowledge needs to be gathered and studied for its value in blending with other knowledge from other cultures.

Folk wisdom is often rare and unique, vitally necessary as we work at building a new world. And folk ways are of even greater value when they are learned from a living culture. Besides the value to us of what we learn, there is a value to them in feeling that their way of life has something to contribute to humanity as a whole. When we learn from what others have to teach we grow in respect for them, increasing the feeling of the interdependency of all.

My house has its origins on the steppes of central Asia. My felt boots came by way of Finland from Asian shepherds. My cucumbers came from Egypt, my lilacs from Persia, my boat from Norway, and my canoe is American Indian. My crooked knife for paddle-making is Bering Coast Eskimo, my axe is a nineteenth-century Maine design, and my pickup is twentieth-century Detroit. The list is long. The more our knowledge increases, the greater becomes our awareness of indebtedness to others. We are each a cultural blend. So why not recognize this truth and deliberately make use of the possibilities for a better way of life, whether in medicine, agriculture, child care, architecture, or a host of other areas?

LEARNING FIRSTHAND

If it is true that folk wisdom is our basic wealth, the chief insurance of a culture’s worth, then we are nearly bankrupt. Traditional knowledge is disappearing at an accelerating rate, as the creations of local craftspeople are replaced by factory-made products, which are not designed with a concern for the improvement of human life but merely for profit. We need to be collecting as many examples as possible of the old knowledge and skill, before they are forgotten and lost forever.

Learning to plant a garden from a Mexican village family provides insight and perspective that has various advantages over similar information obtained by reading a book. Living and working in the village, partaking of the whole atmosphere, may suggest new ways of using this knowledge when at home.

There is no I

(except ego-centrically)

Only a wonderful

We

Part of me is Grandmother

Part Emily D.

Part Scott Nearing

(Who was part H.D.T.)

Part every person I’ve ever met

Whether in life or in lit.

’Tis delightful—being this blend—

This

We.

If we delegate such learning, we should be sure to select sensitive, observant, and empathetic researchers, because their inputs of thinking may make the knowledge gathered many times more useful.

We should also aim to do more than merely ape other cultures. Only through careful selection can we design a culture that fits our own particular needs.

Sitting on the floor may presently be a fad for Westerners. Yet there is something to be said for the simplicity of sitting on a chair or bench: you spend less energy getting up and down; and the floor is usually the coldest part of the room, so raised chairs and beds are sensible in a chilly climate.

Inflated seal skins make excellent boat rollers for an Eskimo, but they deteriorate rapidly where it is warmer, so we use their idea for our soft-tired vehicles but substitute rubber for seal skin, another cultural blend.

INTERDEPENDENCE

Have you ever known someone who, after cutting a finger or developing a blister, said: “Oh, it’s nothing—it’s just my finger . . .”? Yet the finger is an essential part of the whole body, and through that finger the entire organism is impaired. Moreover, the whole organism assumes responsibility for healing the hurt part. Just as the finger is an extension of the physical body, so each of us is an extension of the social body. Whatever we do as individuals affects the whole, and what other individuals do affects us. These effects may not be visible for some time, as with a teredo worm boring into a ship’s bottom, yet the results are no less real for being unseen at first. However small the individual holes, the ship will sink.

Years ago I began to recognize my kinship with all living beings, and I made up my mind that I was not one whit better than the meanest on earth. I said then, and I say now, that while there is a lower class, I am in it; while there is a criminal element, I am of it; while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.

—EUGENE V. DEBS

For me, one of the attributes of maturity is that we reach that stage when we act as though whatever happens to society happens to us. We will no longer feel good when we hear of the devaluation of the euro, the ruble, the peso. We, too, will feel the financial losses of people in other countries, knowing the suffering these changes bring. The waste of lives and minds because of poverty is my business, and yours. When a crime is committed, it is some part of our own social body which commits that crime.

War in Nigeria . . . It is our body that suffers there. Starvation in Bangladesh . . . It is our children who hunger. A riot in a distant city? That is our city, our heads being broken. Unemployment, welfare checks, slum conditions—all are ills of our body. If that small portion of the social body that I identify with locally is to stay healthy, I must work to see that the whole is healthy.

ENLIGHTENED SELFISHNESS

We have been taught that “selfishness” is bad, and in general, this is a useful and necessary rule. As a society, we condemn selfishness as too great a concern for one’s own being. Narrow, crabbed, ignorant selfishness hurts others and ourselves.

Yet this principle may be at odds with a more inclusive conception of the social body. Perhaps the problem is not selfishness, because it is normal for an organism to be concerned with its own welfare, but rather shortsighted or unenlightened selfishness that supposes it can achieve well-being at the expense of others.

When we see the social body as an extension of ourselves, narrow definitions of selfishness drop away. What we need is not less selfishness but a less narrow selfishness. We need selfishness that’s enlightened, to the point where we see that our welfare is inextricably intertwingled with the welfare of all. Through enlightened selfishness I can recognize my neighbor’s need as my own.

OUR COMMON INHERITANCE

Down through the ages we have been gaining in knowledge, each generation standing on the shoulders of those who have gone before, and we have been coming closer and closer to launching into flight.

The prejudice and hatred that lead to war belong to the mixed-up adolescence of humanity. A mature society, like a mature human being, can recognize the tremendous advantages of cooperative effort over competition.

We are not wiser, we are not better, we are not stronger than our predecessors, but we have their accumulated knowledge and wisdom to build upon. We have gained in understanding and technical knowledge: this vast treasure house is our inheritance. With the creative intelligence of the people now living combined with wisdom developed over the centuries, we may create a self-sustaining flame of human happiness.

You say, “Isn’t it sad that a diamond, when seen to its essence, is nothing but common carbon?” I say, “Isn’t it wonderful that common carbon, in its most developed form, is the finest of diamonds?” You say, “Isn’t it sad that altruism, when seen in its basic structure, is nothing but base selfishness?” I say, “Isn’t it marvelous that base selfishness, in its most enlightened form, is the purest of altruism?”

—PIERRE CERESOLE

When love and skill work together, expect a masterpiece.

—JOHN RUSKIN

A Democratic Axe

It is hard to find a good broad hatchet—a small, broad axe with a wide cutting edge beveled on only one side, like a chisel; this special bevel makes it easier to hew to a line.

After forty years of hunting in antiques shops and flea markets, I have found only two broad hatchets that passed muster. To friends who sought one of their own, the outlook was discouraging. They could get one made—if they happened to know a good blacksmith, if they had a good design, and if they could afford the price.

Or you could forge one yourself, but by the time you had learned to make a fine one, you would have become a blacksmith yourself. This is an elite tool.

In Japan, in the Tosa region of the island of Shikoku, I was surprised by the number of blacksmiths. Each village had its smith, and all could make excellent edge tools. It was delightful to see the grace and skill of those smiths. I became friends with one who made a broad hatchet to my specifications. Twenty years went by, and in the interim I had studied many axes and was blending what I had learned into my ideal of a broad hatchet.

A few years ago I carved a pine model and sent it off to my blacksmith friend in Shikoku. Yes, he would make it for me. Two years passed and it did not appear. I assumed the project was forgotten.

While visiting Italy, I came upon an elderly smith who had made axes years ago. I carved another pattern, and he forged the axe. Now, these are far from democratic tools. To get one you first have to design it and then know a smith in Japan or Italy or wherever who can—and is willing to—make an axe from your design.

It was doubtful that the axe from Japan would materialize, and the Italian smith was very old and sick and would probably not make another. A good broad hatchet for students and friends who wanted one was as elusive as ever. And though this axe adventure was exciting, and I had acquired some fine ones, we badly needed to have some inexpensive ones available.

While studying in Switzerland the breakthrough came. The tiny fellow who lives upstairs above my right ear (and works mostly at night) shouted “Eureka!” He presented me with a full-blown design for a democratic axe.

I could hardly wait to get back to my bench. For steel there was an ancient plow point of about the right thickness lying behind the barn. Into the bonfire it went and when glowing red, we heaped ashes over it and let it remain until morning, cooling slowly and releasing its hardness. Next day I reheated and hammered it flat using a handy ledge for an anvil. When it cooled, I drew the pattern on it. Three hours of work at the vise was needed to cut it to shape with a hacksaw and another hour to dress it with files.

For us amateurs in axe making, there are two major difficulties. One of these is forging the eye of the axe—the hole into which the handle is inserted in a conventional axe. This democratic design eliminates the eye. The other difficulty is tempering, or bringing the steel to the correct hardness. Smiths have long been respected for their skill at this magical process of tempering steel, which requires good judgment and much experience to be able to do dependably.

After a good deal of pondering, experimenting, and reading all that I could find on tempering, some of the mystery began to fade. Before tempering, the steel must be hardened by being brought to red heat and then plunged in water. Then it seemed that tempering was merely a matter of temperature control. So we put the axe in an oven set at 475°F for half an hour and let it cool slowly. This worked!

Now, you smiths may object, reminding us that a tool like an axe that gets a blow needs to be soft in the eye to resist breaking. To this charge I plead nolo contendere. However, a broad hatchet is made with a short handle for use on a block, and such hatchets do not undergo the same severity of blows.

For the first time, we now have a democratic axe—an axe that most anyone who wants one can have. (You say you never knew you needed an axe, and I say, very well. Even so, here we have another example of one more democratic tool, which will make design of the next one a little easier, whatever its purpose.)

This experience with the broad hatchet is important for me on several levels. First it has been a exciting adventure all along the way, from learning to appreciate the variations in different forms of such a basic tool, to designing my own which others made, to ultimately making my own. Another level of the adventure is to be able to help others make their own hand axes and in the process gain the confidence that comes from making a tool. This process demonstrates how we can have adventure in a variety of ways: designing, working with the hands, and working with the mind as we carry the concept of democratic things further.

Another value this experience has had for me is the breaking of mental and social barriers, which we need to be able to do if we are to solve our problems and create a decent society that works for all people.

At times the outlook appears very dark. It would seem our problems are insurmountable. As with this little hand axe, I was quite sure that I would never make my own. And yet, without consciously focusing on the problem directly, unconscious forces were at work and discovered a solution. This gives me hope that if we can continue searching and caring and supporting one another—we may be able to find the solution to even our worst problems.

P.S. The broad hatchet from Shikoku finally arrived. It is a veritable gem. Actually, two came—a left- and a right-handed one—polished to a mirror finish and gently wrapped in small white towels.

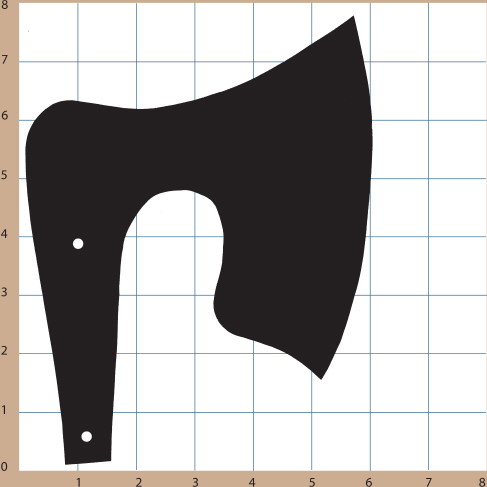

To Make an Axe:

1. Trace the pattern on the next page on annealed (temperable) steel, 5/16-thick.

2. Cut out the axe head with a hacksaw.

3. Smooth all edges with a file, and file the bevel to make the cutting edge. (For a right-hander, the bevel should be on the right, for a lefty on the left.)

4. Drill two rivet holes.

5. The face should be slightly hollowed, like a shallow gouge. To do this, carve a hollow (6 inches long and 1/4 inch deep) in a chopping block. Heat the axe head until it is glowing red, then hammer it into the hollow with the bevel side up.

W. Coperthwaite

6. To harden the steel, heat it to glowing red and plunge it immediately into cold water.

7. To temper the steel, put the axe head in an oven at 475°F for about twenty minutes and allow to cool slowly.

8. Carve a handle of hardwood in the form shown in the photograph and rivet it to the axe head. You can customize the handle’s curve and weight to your own preferences.

If one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.

—HENRY DAVID THOREAU

A template for the democratic axe. Scale is in inches.

*My answer is: My brothers and sisters are quoted throughout this book.